Explain how the focus on innovativeness can influence a firm s success

Explain how the focus on innovativeness can influence a firm s success

4 Reasons Why You Need To Focus On Innovation

Innovation is a differentiator

Each day, innovators in the business world create new products, methods, and ideas. They manage to look at problems differently and come up with solutions others cannot, and they provide an endless stream of value to their companies. In fact, innovation just might be the most important component of a successful company.

Look at the reasons innovations is so important, and you will have a better understanding of why you need to innovate every chance you get.

Grow in Leaps and Bounds

Sixty-six percent of respondents in The Deloitte Innovation Survey 2015 stated innovation is important for growth. Businesses that innovate are able to scale up and add more employees. That allows them to take on more customers and grab a bigger share of the market.

Innovation makes it easier to grow, regardless of the size of the business. You might have a small startup, but if you innovate, you can grow your business. The same is true for a fortune 500 company. It might be a huge corporation, but it can take even more of the market share if it manages to innovate. It’s easy for innovative companies to grow.

Stand Out from Competitors

Your company fits inside of a specific niche or industry, and it’s far from alone. Let’s say, for example, you manufacture light bulbs. Tons of companies also manufacture light bulbs, and you need to stand out in some way. You can do that through innovation.

The right innovation will allow you to offer something unique to your customers. For instance, what if you managed to create a light bulb that automatically turned off when people left the room? That’s a crazy example, but that’s how some of the best innovations work. Top innovators take popular products and make them even better. That makes brands stand out in the market and makes it easy for companies to increase revenue.

Meet Customer Needs

Customer needs are constantly changing. One day, your customers might need exactly what you have to offer, and the next day, they might need something else. Innovators predict changes in the market and provide solutions before people even realize they need them. You cannot meet your customers’ needs on a long-term basis unless you are willing to innovate. If you remain stagnant, your business will eventually flounder. You have to come up with new ideas that excite your customers and meet their needs if you want to have staying power.

Attract the Best Talent

Talented, innovative people want to work for innovative companies. You aren’t going to attract someone who is going to create the next big thing unless your company has a history of creating. Innovators want to be challenged and encouraged to create on a regular basis, so you need a culture of innovation to recruit that talent. Make a name for your company by being innovative and then watch the resumes pile in. Innovators from all over will want to work with you, and then something magical will happen. Your company will become even more innovative. You will experience more growth, stand out from competition even more, and meet your customers’ needs in ways you never imagined. That’s when your company will reach an entirely new level.

It’s normal to want to maintain the status quo. You assume that since it’s worked for you in the past, it will work for you in the future. In reality, the status quo only works for so long. If you’re going to keep your doors open, you have to innovate. You need to take the risks that come with innovation so you can enjoy all of the rewards.

The Importance of Innovation – What Does it Mean for Businesses and our Society?

According to McKinsey, 84% of executives say that their future success is dependent on innovation. Although innovation may sound like a buzzword for some, there are many reasons why companies put a lot of emphasis on it.

In addition to the fact that innovation allows organizations to stay relevant in the competitive market, it also plays an important role in economic growth. The ability to resolve critical problems depends on new innovations and especially developing countries need it more than ever.

We’ve written quite a few posts about innovation management and this time, we’ve decided to take a closer look at the reasons that make innovation important for an individual organization and the society at large.

Table of contents

What is innovation and why do we need it?

Because organizations are often working with other individual organizations, it can sometimes be challenging to understand the impacts of innovation on our society at large. There is, however, a lot more to innovation than just firms looking to achieve competitive advantage.

Innovation really is the core reason for modern existence. Although innovation can have some undesirable consequences, change is inevitable and in most cases, innovation creates positive change.

We’ve decided to look at the outcomes of innovation on macro and micro level:

Macro perspective: The role of innovation in our society

Over the last decades, innovation has become a significant way to combat critical social risks and threats.

For example, since the Industrial Revolution, energy-driven consumption of fossil fuels has led to a rapid increase in CO 2 emissions, disrupting the global carbon cycle and leading to a planetary warming impact.

Our society revolves around continuous economic growth, which mainly depends on population growth. The population is shrinking and ageing in the developed counties and is likely to do so in other parts of the world as well.

Innovation is important to the advancement of society as it solves these kinds of social problems and enhances society’s capacity to act.

It’s responsible for resolving collective problems in a sustainable and efficient way, usually with new technology. These new technologies, products and services simultaneously meet a social need and lead to improved capabilities and better use of assets and resources.

In order to be able to solve these kinds of societal problems, private, public and non-profit sectors are involved.

The fundamental outcomes of innovation

Because innovation has an impact on so many different parts of our society, it would be almost impossible to go through everything in one post. Therefore, we’ve decided to focus on the most significant aspects related to the importance of innovation.

In general, the result of innovation should always be improvement. From the society’s perspective, the fundamental outcomes of innovation are economic growth, increased well-being and communication, educational accessibility and environmental sustainability.

Economic growth

Innovation is responsible for up to 85% of all economic growth.

The latter describes the essence of innovation quite well. The purpose of innovation is to come up with new ideas and technologies that increase productivity and generate greater output and value with the same input.

If we look at the transformation of the US, once a largely agrarian economy that advanced from emerging nation status in the mid-19 th century to an industrial economy by the First Wold War, we can see that the agricultural innovations and inventions were actually one of the largest factors that helped bring about the Industrial Revolution.

Vast improvements in agricultural productivity had already previously transformed the way people work in Europe, releasing farmers for other activities and allowing them to move to the city for industrial work. The shift from hand-made to machine-made products increased productivity, directly affecting living standards and growth.

If previously one worker was able to feed only a fraction of their family, it was now possible for one person to produce more in less time to provide for the entire family.

Innovation and the future of jobs

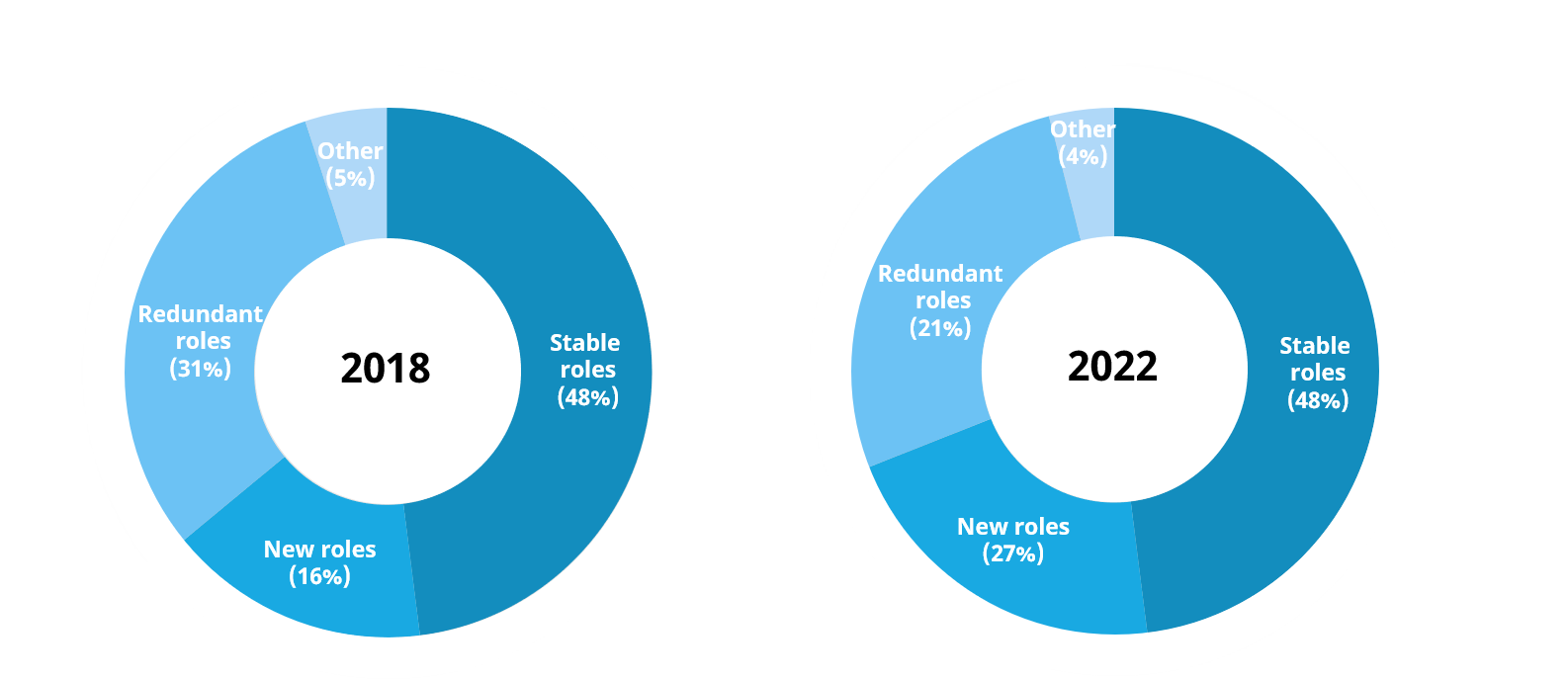

Technological advancement and increased productivity means major changes for careers today as well. The world economy could more than double in size by 2050 due to continued technology-driven product improvements.

According to the new World Economic Forum report, nearly 133 million new jobs may be created by 2022 while 75 million jobs are displaced by AI, automation and robotics.

Manual, low-skilled jobs and middle-income roles such as accountants, lawyers and insurance clerks are the ones that will be affected the most over the next decade.

The biggest issue here isn’t necessarily that these jobs would disappear completely but the fact that polarization of the labor force becomes more significant. New skill sets are required in both old and new occupations.

How and where people work will also continue to change. There will be more demand for experts, whereas «regular workers» are at risk of having to settle for low-income positions.

Increased well-being

However, not all of the benefits of innovation and growth are evenly distributed. Often, a rise in real GDP means greater income and wealth inequality. Although there isn’t a threshold level for how much inequality is too much, greater socioeconomic gaps are most likely have some negative consequences.

In theory, income inequality isn’t a problem itself except when the concrete purchasing power decreases. In practice, however, it does have a number of impacts on our society and collective well-being.

Reduced sickness, poverty and hunger

As already mentioned, developing countries depend on innovation as new digital technologies and innovative solutions create huge opportunities to fight sickness, poverty and hunger in the poorest regions of the world.

Developed countries also rely on innovation to be able to solve their own problems related to these themes.

What comes to reducing hunger, for example, agricultural productivity is critical in the developing countries where the next population boom is most likely to take place. Smallholder farms in developing countries play an important role as up to 80% of the food is produced in these communities.

Developing and sharing agricultural innovations such as connecting farmers to information about the weather, has proven to be an efficient way to help farmers stay in business. Although this is just an example of how innovation can help people continue producing food, innovation provides endless other opportunities that can eventually help reduce poverty and hunger around the world.

Communication and educational accessibility

You probably already knew that The World Wide Web celebrates its 30 th birthday this year. We’ve already seen a huge technological revolution during the past decades and continue to do so in the future.

According to the World Bank Annual Report 2016, even among the poorest 20 percent of the population, 7 out of 10 households have a mobile phone. This means that more people now have mobile phones than sanitation or clean water.

Also, the mobile worker population is expected to grow from around 96 million to more than 105 million by 2020. I nnovations in mobile technology such as voice control and augmented reality are enabling workers in completely new ways.

Technology innovation can also help rural areas thrive and become more sustainable. Although there are some barriers to technology adoption, such as low income or user capability, more people can access information an improve their knowledge despite their socio-economic position or demographic area.

Environmental sustainability

Sustainability and environmental issues, such as climate change, are challenges that require a lot of work and innovative solutions now and in the future.

Earth suffers as consumerism spreads and puts consumption at the heart of modern economy. Although consumerism has a positive impact on innovation as a source of economic growth, the rising consumption of innovative products is often considered as one of the reasons for environmental deterioration.

Often, politics or other methods aren’t enough to make a change – at least not quick enough. Policy changes take time to take effect, which is why the long-term survival of our society and nature depends on new, responsible innovative technologies.

Although new greener technology solutions, such as eco vehicles aren’t necessarily more competitive alternatives to petrol-powered vehicles just yet, they will definitely offer many advantages for the future.

Micro perspective: The importance of innovation for an organization

Now that we’ve looked at the role of innovation from the society’s perspective, we can take a closer look at the importance of innovation for organizations and businesses.

In general, it’s difficult to identify industries where innovation wouldn’t be important. Although certain industries depend on innovation more than others, innovation and the ability to improve considers everyone.

In general, innovation can deliver significant benefits and is one of the critical skills for achieving success in any business.

Competitive advantage

Competitive advantage means the necessary advancements in capabilities that provide an edge in comparison to competitors of the industry. What these are exactly, depends on your business model and the industry you operate in.

As already mentioned, for organizations the ability to get ahead of the competition is one of the most significant reasons to innovate. Successful, innovative businesses are able to keep their operations, services and products relevant to their customers’ needs and changing market conditions.

Innovation increases your chances to react to changes and discover new opportunities. It can also help foster competitive advantage as it allows you to build better products and services for your customers.

Maximize ROI

Increased competitive advantage and continuous innovation often has a direct impact on performance and profitability.

Although measuring the ROI of innovation might be challenging especially in the beginning or when talking about disruptive innovations, investing in innovation is often a surer way to improve your numbers than not innovating at all.

Increased productivity

Economic growth is driven by innovation and technological improvements, which reduce the costs of production and enable higher output. If we look at this from the perspective of an organization, different automation solutions decrease manual, repetitive work and release time for more important, value-creating tasks.

Improved productivity and efficiency makes work more meaningful as less time needs to be spent on low impact tasks. The more time you’re able to spend on tasks that have a direct impact on your business, such as improving processes, solving problems or having conversations with your customers, the more likely you’re able to actually reduce costs, increase turnover and provide your customers with solutions that truly benefit them.

Positive impact on company culture

Innovation practices can help build a culture of continuous learning, growth and personal development. This type of innovative environment can again motivate people to constantly improve the way they and their team work.

If you look at history, innovation doesn’t come just from giving people incentives; it comes from creating environments where their ideas can connect. – Steven Johnson

When the entire organization is supportive and provides the right tools for the employees to succeed in their jobs, it eventually has a positive effect on how people perceive their jobs.

Conclusion

Generally speaking, the main purpose of innovation is to improve people’s lives. When it comes to managing a business, innovation is the key for making any kind of progress.

Although your innovation activities aren’t necessarily powerful enough to save the world, you should focus on improving the things you can affect.

Small improvements eventually lead to bigger and better ideas that may one day become revolutionary. In the meantime, however, you’re responsible for finding ways to make improvements in your own sphere of influence.

Often, getting started is the hardest part as there are many ways to approach innovation. Our suggestion is to simultaneously work on developing your personal skills and business related aspects. You should, however, start small and pick your focus as it’s impossible to achieve everything at once.

If you want to start with innovation, we encourage you to try Viima. It’s free for unlimited users!

This post is a part of our Innovation Management blog-series. In this series, we dive deep into the different areas of innovation management and cover the aspects we think are the most important to understand about innovation management.

You can read the rest of the articles in our series covering innovation management by clicking on the button below. Don’t forget to subscribe to our blog to receive updates for more of our upcoming content!

How the focus on innovativeness can influence a firm’s success

| Sana | 08.04.2022 |

| Hajmi | 12,71 Kb. |

| #536648 |

Bog’liq

Test Essay for CoolClub

How the focus on innovativeness can influence a firm’s success.

There are many firms around the whole world. And number of firms are growing. So competition between them is increasing too. Each of these develops day by day. This means staying between advanced and developed firms are more difficult than yesterday. It requires coming up with new idea from leaders of companies. Nowadays we can’t imagine big firms without innovations. I think innovations are key at leading between competitive groups. So why? Innovations firstly are big comfort, convenience and easiness. These parameters always attract clients and people choose this. Imagine, we have a firm which has a lot of clients around the country. And many years we service to people exactly qualitatively. If we don’t think about making innovations at manufacturing of our firm, surrounding opponents pick up our clients easily. Because, in the world, where new technologies and innovations are creating, we can’t stay at the top without any new ideas. Yes, we can expand our manufacturing by growing number of workers and staffs, by opening new firm branch, by raising production quantity and others. But to innovate, to introduce new technologies give many chances to raise with big steps. For example, it gives us come up with a new design of buildings or head office, using new devices which with we can improve quality of our products (for example, fast food center), to raise speed of manufacturing, using smart equipment, by creating new apps and sites of our firm we can attract more peoples, giving them chance to use our services from applications by e-commerce without leaving home. The second way of which we listed above is significantly more and quickly gives results. To innovate should never stop, even occasionally. Because rise to the top is difficult, but staying there more difficult. So influence of innovativeness one of the main factors firm’s success.

Intangible Capital

CiteScore Rank (Scopus)

Intellectual capital and system of innovation: What really matters at innovative SMEs

Miguel González-Loureiro, Pedro Figueroa Dorrego

University of Vigo (Spain)

Received August, 2011

Accepted June, 2012

GONZÁLEZ-LOUREIRO, M.; FIGUEROA DORREGO, P. (2012). Intellectual capital and system of innovation: What really matters at innovative SMEs. Intangible Capital, 8(2): 239-274. http://dx.doi.org/10.3926/ic.273

Purpose: The aim is to try to build a model for measuring and assessing the simultaneous effect of the three components of the intellectual capital (IC) management on the growth of innovative SMEs. In this first stage of research, the model was tested in a representative sample of innovative SMEs from Galicia, where the performance construct was the cumulative growth measured in a three years period.

Design/methodology/approach: This empirical work has been designed with the aim of (1) selecting the best variables from each IC component (human capital-HC, structural capital-SC, and relational capital-RC) at innovative SMEs for explaining cumulative growth; and (2) assessing how much the IC management at innovative SMEs could contribute to their growth. A structural equation model is developed and tested. It allows the identification of the key variables that innovative SMEs are encouraged to manage (17 variables in the current stage) for boosting their growth.

Findings: In the Galician case, HC is the basic, starting point for the SMEs’ growth. HC seems not to be able to directly influence on growth if not through SC and, in a very low degree, through RC. Thus, the key seems to be the SMEs’ capability for transforming valuable knowledge from the HC into organisational value (i.e., SC).

Research limitations: The limited sample of 140 SMEs and the regional scope (Galician region) may limit the possibility for directly spreading findings. However, the double test developed (cumulative growth measured in two year and in three year period) and the improved overall goodness fit indexes, both allow pointing out to a future research where final variables can be set.

Practical implications: Results could allow SMEs practitioners a better understanding about variables of IC on which they ought to focus their management efforts. In the case of public decision-makers, outcomes could inform about the key aspects that they should improve for playing a more decisive role in the innovative efforts of SMEs.

Originality/value: The originality of this research could be twofold: the medium-term perspective for assessing impacts, and the inclusion of the agents from the system of innovation in the RC component. The latter has allowed assessing the contribution of the institutional system for supporting innovation in the case of SMEs. The former has allowed identifying cause-effect interactions among IC components to explain growth.

Keywords : intellectual capital, system of innovation, structural equation model, innovative SME, growth

1. Innovation and intellectual capital framework as a key elements for SME’s growth

Despite the lack of a unique definition of intellectual capital (IC henceforth), it is usually referred as the intangible- invisible assets or knowledge resources that are able to create value in firms. European Commission (2006) has defined IC as a combination of activities and intangible resources (human, organisational and relational) of an organisation, that enables it to transform a set of material, financial and human resources to a system capable of creating value for stakeholders. Therefore, the IC must be considered as one of more intangibles. In fact, IC can be considered as “[…] the knowledge owned by the organisation (explicit knowledge) or by its members (tacit knowledge) that creates or produces current value for the organisation […]” (Simo & Sallan Leyes, 2008: page 71).

Key elements for success, as well as the nature and extent of barriers to innovation in SMEs, were also studied. For example, some authors highlight the innovation as the outcome from a knowledge-based process which converts knowledge into business value (Roper et al., 2008). They find that the innovation value chain plays a key role in the innovation success. They find that knowledge is positively related to innovation success in the process of value creation, but there is a lack of information about the elements that most can contribute to this success.

The links among innovation activities and growth in innovative SMEs was studied in a descriptive approach for a 3-year period using the average annual rate of growth (Freel & Robson, 2004). The authors report relevant findings regarding positive and negative relationships among different types of innovation (novel and incremental) and several growth measurements. Although they studied the impact of innovation activities on growth, there was no clear identification of other factors that could influence growth, from a more holistic vision of an SME.

Concerning the relationships among the environment and innovation processes in SMEs, it was also detected a need for deepening in the links between the so-called institutional support system for innovation (ISI, henceforth) and innovative SMEs (Mancinelli & Mazzanti, 2009). The system of innovation is part of the innovative SMEs environment. Such system should be understood as Freeman (1987) tried to define it: the network of institutions from both the private and public sector, whose activities and interactions start, import, modify and diffuse new technologies. It should be mentioned the relevance of such definition under a systemic focus, as it helps to approach and conceptualise the relationships among systems (mainly, open systems).

This lack of research is addressed in this paper from an IC approach, with the aim of identifying the combination of intangible components (human, structural, relational) at innovative SMEs that enables these organisations to transform a set of material, financial and human resources to a system capable of creating value. The paper follows a different approach to previous works, which lack a more structured vision of the enterprise and, more specifically, of SMEs. As stated by McAdam, Moffett, Hazlett and Shevlin (2010), there is a need for further developing models to clarify how, why, and where value is generated through innovation and intangibles management.

Thus, authors would like to suggest that an IC approach could provide a more eclectic view of the different elements that could affect the results of the innovation process and, consequently, the growth of SMEs. And both topics, IC and ISI, seem to be very suitable to address the lack of empirical test about IC management at innovative SMEs.

This paper introduces one more year in the cumulative growth rate already analysed in a previous research (González-Loureiro & Figueroa Dorrego, 2010), where a period of two years was considered. From there, the maintenance of the main variables, still present in the current model, is pointing out a future model for measuring the SMEs’ IC, where further research is needed yet.

The remainder of the paper is organised as follows. Section 2 contains a briefly reflection on the theoretical context about IC and ISI, including links among IC, innovation and growth. Section 3 presents the proposed model, applying the literature premises on IC to the case of innovative SMEs. There, a structural model equation is developed to identify the relationships between IC components and cumulative growth at innovative SMEs. Section 4 describes the empirical work, including the development of a cross-sectional survey and the usual statistical procedures used to evaluate the results. A discussion of the empirical findings as well as limitations is also included in that section. Section 5 presents the main findings and conclusions on the links among IC components that best explain growth in innovative SMEs. Those linkages are expressing cause-effect relationships because IC was measured previously in relation to cumulative growth.

2. Intellectual capital management and innovation at SMEs

Intangible management has focused mainly on five research topics:

-Knowledge systems, which facilitate the identification, acquisition, development, distribution, use and retention of knowledge flow throughout the organisation (Probst & Büchel, 1997; Davenport & Prusak, 1998). The key factor is knowledge as a system.

-Knowledge transformation, with a focus on explaining how it can and should be managed for knowledge exchange (Polanyi, 1962; Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995). The key factor is the knowledge transformation process.

-Organisational learning, which emphasises methods for acquiring knowledge through learning within an organisation (Senge, 1992; Argyris, 1993). The key factor is how to convert the inherent knowledge of individuals to knowledge that remains within the organisation.

-Capabilities management, which involves the management of human capital comprising skills, attitudes and knowledge (Prahalad & Hamel, 1990; Zack, 1999). The key factor is human capital empowerment.

-IC, which involves the measurement, assessment and quantification of intangibles in an organisation because of their ability to create value (Edvinsson & Malone, 1997; Sveiby, 1997). The key factor is measurement of intangibles as an input to facilitate efficient management.

From a strategic approach, IC and, more specifically knowledge, are used to create and manage intangibles and, thus increase the value of an organisation (Roos et al., 1997). Intangible assets are enablers, as they transform productive resources into value-added assets (Hall, 1992). Therefore, strategic and measurement streams are fully complementary. Comprehensive structures and classifications of models for measuring IC elements have been developed, achieving up to 42 different models (Sveiby, 2010). However, further empirical research is still required to identify the interactive effect of those linkages for assessing how much it contributes to the overall generation of value.

There are also a wide range of references regarding the need for appropriate corporate governance indicators linked to knowledge and intangibles in SMEs. Some authors state that business success is based more on strategic management and intangibles as resources, while is less based on physical and financial resources (Bontis, 1998). Choo and Bontis (2002) also claimed that knowledge is the most important strategic resource for a business. Competitive advantage based on knowledge is perhaps the most sustainable in the medium term (Sveiby, 2007). This could indicate that competitive advantages that are sustainable over time should result in superior business performance (Peteraf, 1993) and, thus, growth. However, this must be further empirically tested yet.

There is a consensus that IC can be split into three main elements: human capital, structural capital and relational capital (Edvinsson & Sullivan, 1996; Bontis, 1996; Sveiby, 1997; European Commission, 2006). There are several definitions for each element, summarised as follows:

-Human capital (HC henceforth) can be defined as a set of values, attitudes, qualifications and skills held by employees that generate value for firms (Roos et al., 1997; I.A.D.E-C.I.C., 2003; European Commission, 2006).

-Structural capital (SC henceforth) is the worth and value created within the organisation that remains when employees go home. Therefore, it requires a high level of formalisation to avoid dependence on people and to remain within the organisation (Roos et al., 1997; Ordóñez de Pablos, 2004; I.A.D.E-C.I.C., 2003; European Commission, 2006).

-Relational capital (RC henceforth) is the result of the value generated by firms in their relations with the environment, including suppliers, buyers, competitors, shareholders, stakeholders, and society. It is the result of an organisation’s ability to interact positively with members of the community to which it belongs to enhance wealth creation through their HC and SC (Viedma Marti, 2001; I.A.D.E-C.I.C., 2003; European Commission, 2006).

Organisation capabilities are based on knowledge, tacit knowledge as Marr, Schiuma and Neely (2004) state. Accordingly, the firm´s knowledge must be managed efficiently to achieve better both economic and social performance. Precisely, IC management is the process of extracting value from knowledge (Egbu, 2004). It has been suggested that the greater are the interrelationships among HC, SC and RC, the greater is the value generated. Some authors have identified some links among elements of firms, measured by their IC (Bontis, 1998; Do Rosário Cabrita & Bontis, 2008; Halim, 2010). Bontis (1998) developed a model linking variables of IC and a set of business performance variables. He concluded that causal relationships exist between various elements of IC and explanatory variables for corporate performance. Sales and profit growth were included in the construct in addition to some other static performance indicators, but value added was not.

Thus, it can be suggested that IC theories help to identify where the value is generated and what the key elements are for explaining the value creation process. However, little literature has been found concerning cumulative growth thanks to IC on SMEs.

On another hand, there is an increasing trend to relate the innovation capacity of an organisation to knowledge management, measured in terms of IC, as reflected in the Oslo Manual (OECD, 2005). For innovative companies, particularly those that are technology intensive, intangible assets often play a critical role in business success (Sánchez et al., 2001).

There is a relative consensus that measures of growth must be multi-dimensional in this type of research (Venkatraman & Ramanujam, 1986). So, we suggest that a model which mixes IC with monetary measures is suitable for obtaining further information about where and how much IC affects growth. A great deal of the research on this topic has found that financial measures (return on assets, operating margin, etc.) provide information about the past (Venkatraman & Ramanujam, 1986; Kaplan & Norton, 1992). Conversely, non-financial measures (market share, market value of shares, etc.) provide information about the expectations of stakeholders regarding the future development of the company. The models that include multi-dimensional indicators provide a better understanding of business performance (Kaplan & Norton, 1992).

Innovation enables firms to achieve sustainable competitive advantages and this is a key factor for growth (Cheng & Tao, 1999; Van Auken et al., 2008). Higher value added ratios can arise from creativity, which is derived from the intangibles managed by a firm (Bontis, 2001). Thus, several links exist among innovation, IC and growth.

Figure 1. Interpreting the Multichannel Learning Model. (Adapted from Caraça et al., 2009: page 866)

Several authors emphasise the interactions among the ISI components, as well as between them and components outside that system (Metcalfe, 1995; Lalkaka, 2002; Kayal, 2008). ISI has been usually developed from a geographical approach (mainly national vs. regional), or from a business approach (sectoral vs. technological). Nevertheless, such approaches have not solved the challenge of internationalisation, because agents are multileveled (especially, the public sector) in an international environment (business, scientific system and universities…). The ISI researchers are studying the possible linkages among the business system (where companies do not have to be related commercially), the business networks and the ISI. Those are the main influencing factors on the innovation performance of the whole business system of a region or even in the industrial clusters within a region (Chang & Chen, 2004: page 28).

The points discussed above indicate that more detailed research on the links among components of IC and growth in innovative SMEs would be beneficial. The results of such research would help SMEs managers to identify the hidden key components that most influence growth in their innovative activities. The research should also take into account possible simultaneous effects among interrelated components, because changes and improvements in one component (HC, for instance) can affect another (RC, for example), as we introduce in the next section.

3. Proposed model: Measuring the combined effect of IC components on growth at innovative SMEs

This section introduces the hypotheses and the model to be tested empirically. In this current stage of development, we have tested it in a sample of Galician innovative SMEs. The measures for each IC component and for growth are justified based on the literature. Chen, Zhu and Xie (2004) have found evidences proving that IC components affect positively to enterprise performance. The higher is the interactions among the three IC components, the greater is the effect on growth.

The model introduced here is an evolutionary form of the one presented at González-Loureiro and Figueroa Dorrego (2010). There, the model was tested with a two years cumulative growth rate. Here, growth is measure in a three year period.

The following hypotheses are proposed for building the causal model for measuring the simultaneous effect of the three IC components (HC, SC, RC) on cumulative growth (see figure 2):

-(H1) HC proxy variables are directly and positively related to SC proxy variables.

-(H2) HC proxy variables are directly and positively related to RC proxy variables.

-(H3) SC proxy variables are directly and positively related to the cumulative growth rate of the enterprise (cumulative growth rate of turnover and gross value added in a three year period).

-(H4) RC proxy variables are directly and positively related to the cumulative growth rate of the enterprise.

-(H5) HC proxy variables are directly and positively related to the cumulative growth rate of the enterprise.

-(H6) SC proxy variables are directly and positively related to RC proxy variables.

Figure 2 shows a scheme of the proposed relationships. A few authors have researched similar relationships, but there are significant differences. Bontis (1998) tested a model in which IC components were linked to a multidimensional construct of performance indicators, but he includes customer capital instead of RC. Tovstiga and Tulugurova (2009) related some elements of internal and external IC to a construct of performance outcomes and comparative competitiveness. Taking into account the objectives of their model, these authors disaggregated IC into internal factors (HC and SC) and external environmental factors (socio-political, economic and technological factors). They considered RC as one more element within SC. Thus, the model proposed in this paper has notable differences from previous research: in our case, IC has three components (HC, SC, RC) and the cumulative growth rate is the outcome measured.

The deployment of advanced statistical techniques, such as a structural equation system, facilitates characterising and quantifying those relationships in a simultaneous way. This technique has been used in similar researches on linkages among IC components and some type of performance indicators, such as the research line opened by Bontis (1998) and followers like Martos, Fernández-Jardón Fernández and Figueroa Dorrego (2008), Fernández-Jardón Fernández and Martos (2009) or Do Rosário Cabrita and Bontis (2008). An equation system like this allows considering diverse levels of dependency with overall measures of goodness fit in a unique model. Therefore, it is required to try keeping the model as simple as possible in terms of parsimony: using the less information to explain the proposed linkages.

Figure 2. Relational scheme for the proposed model

The objective of this procedure is twofold: to reduce the number of variables for measuring each component and explain cumulative growth with an efficient number of variables. This is why only first order constructs are developed (the IC components, i.e. HC, SC and RC). However, the categorisation in components, elements and variables is very useful for the purpose of identifying the key variables.

Table 1 to table 3 list the main elements of each IC component. Each element was measured in a questionnaire using a Likert scale from 1 to 5. This scale has been used and validated by several authors in similar research (Zahra & Covin, 1994; Zahra, 1996a; Zahra & Das, 1993; Gallego & Rodríguez, 2005; Fernández-Jardón Fernández & Martos, 2009).

HC elements have been measured through 61 variables, SC through 59 variables and RC through 213 variables. It must be mentioned that this was the first stage for developing this model. In this first step, a high number of variables are needed to select the best from each component. Once achieved, the final definition of this model will be addressed in future research. In the case of RC, it is included the relationships with the “ISI agents” and from the public sector as well. This is a multileveled system: agents from European Union, from Spain and from the Region of Galicia have been included. This explains the high number of variables in this component.

Flexibility and adaptability

Bontis, 1998; Bueno Campos, Arrien et al., 2003

Creativeness and attitude towards innovation

Bontis, 1998; Mouritsen, Larsen & Bukh, 2001; Bueno Campos, Arrien et al., 2003; Chen et al., 2004; Morcillo & Alcahud López, 2005 ; Santos Rodrigues et al., 2007

Motivation / expectations /satisfaction

Bontis, 1998; Bontis & Fitz-enz, 2002; Bueno Campos, Arrien et al., 2003; Alwert, Bornemann & Kivikas, 2004; Mertins, Will & Publica, 2007; Halim, 2010

Bueno Campos, Arrien et al., 2003; Leiponen, 2005; Hayton, 2005; Sharabati, Jawab & Bontis, 2010

Bueno Campos, Arrien et al., 2003; Alwert et al., 2004; Mertins et al., 2007; Halim, 2010

Official/ specialised training

Bontis, 1998; Bueno Campos et al., 2003a; Wang & Chang, 2005

Bontis, 1998; Bueno Campos, Arrien et al., 2003; Chen et al., 2004; Wang & Chang, 2005

Capability for collaborative work group

Bontis, 1998; Cardinal, Alessandri & Turner, 2001; Bueno Campos, Arrien et al., 2003

Capability for communication and exchange of knowledge

Bontis, 1998; Bueno Campos, Arrien et al., 2003; Alwert et al., 2004; Chen et al., 2004; Mertins et al., 2007; Halim, 2010

Total: 61 initial variables

Table 1. Human Capital elements

Denison, 1990 ; Brooking, 1996; Roos et al., 1997; Bontis, Dragonetti, Jacobson & Roos, 1999; Rouse & Daellenbach, 1999; Schneider, 2000; Sánchez et al., 2001; Bontis, 2001; Bontis & Fitz-enz, 2002; Cañibano Calvo, Sánchez, García-Ayuso Covarsi & Chaminade Domínguez, 2002; Bueno Campos, Arrien et al., 2003; Chen et al., 2004; Carmeli & Tishler, 2004;Wang & Chang, 2005; Wan, Ong & Lee, 2005

Bontis, 1998; Bontis et al., 1999; Bueno Campos, Arrien et al., 2003; Chen et al., 2004; Santos Rodrigues, 2008

Nonaka, 1994; Bontis, 1998; Sánchez et al., 2001; Cañibano Calvo et al., 2002; Bueno Campos, Arrien et al., 2003; Chen et al., 2004; Gallego & Rodríguez, 2005; Halim, 2010

Bontis, 1998; Bontis et al., 1999; Bontis et al., 2000; Roos & Edvinsson, 2001; Sánchez et al., 2001; Cañibano Calvo et al., 2002; Bueno Campos, Arrien et al., 2003; Chen et al., 2004; Sharabati et al., 2010

Effort in research, development and innovation

Bueno Campos, Arrien et al., 2003; Chen et al., 2004; Halim, 2010; Sharabati et al., 2010

Sánchez et al., 2001; Cañibano Calvo et al., 2002; Bueno, Arrien et al., 2003; Gallego & Rodríguez, 2005

Total: 59 initial variables

Table 2. Structural Capital elements

Relations with suppliers

Kaplan & Norton, 1992; Sánchez et al., 2001; Cañibano Calvo et al., 2002; Bueno Campos, Arrien et al., 2003; Fernández-Jardón Fernández & Martos, 2009; Halim, 2010

Relations with competitors and allies

Sánchez et al., 2001; Cañibano Calvo et al., 2002; Bueno Campos, Arrien et al., 2003; Fernández-Jardón Fernández & Martos, 2009; Sveiby & Simons, 2002; Adam & Urquhart, 2009; Sharabati et al., 2010; Halim, 2010

Relations with customers

Saint-Onge, 1996; Petrash, 1996; Edvinsson & Malone, 1997; Stewart, 1997; Bontis, 1998; Sánchez et al., 2001; Cañibano Calvo et al., 2002; Bueno Campos, Arrien et al., 2003; European Commission, 2006; Fernández-Jardón Fernández & Martos, 2009; Santos Rodrigues & Figueroa Dorrego, 2010; Kaplan & Norton, 1992; Halim, 2010

Relations with society

Sánchez et al., 2001; Bueno Campos, Arrien et al., 2003; Rodríguez-Pose & Crescenzi, 2008

Relations with inn ovation-supporting institutions

Nelson, 1993; OECD, 1997,1999; Sánchez et al., 2001; Cañibano Calvo et al., 2002; Asheim & Isaksen, 2002; Buesa, Casado & Heijs, 2002; Buesa, Heijs & Martínez Pellitero, 2002; Bueno Campos, Arrien et al., 2003; Asheim, Coenen & Svensson-Henning, 2003; Fritsch & Franke, 2004; Caraça et al., 2006; Fritsch & Slavtchev, 2007; Fritsch & Slavtchev, 2008; Rodríguez-Pose & Crescenzi, 2008; Caraça et al., 2009

Relations with public sector

Sánchez et al., 2001; Bueno Campos, Arrien et al., 2003

Total: 213 initial variables

Table 3. Relational Capital elements

Table 4 lists the two dimensions of growth as the response variable in the model. Information about growth in turnover and value added was obtained from official accounts filed by SMEs in the Commercial Register. SABI database was used to obtain such indicators for each SME.

Zahra, 1996b; Edvinsson & Malone, 1997; Bontis, 1998; Chen, Cheng & Hwang, 2005; Wang & Chang, 2005; García-Merino, Arregui-Ayastuy, Rodríguez-Castellanos & Vallejo-Alonso, 2010

Table 4. Growth variables

For innovative companies, the effect of innovations on performance is affected by a time lag between development of an innovation and results derived from it. This period is not clearly fixed and differs from the time when an innovation is developed and an economic outcome is obtained (Zahra & Das, 1993; Zahra, 1996b; Zahra & Bogner, 1999; Kanter, 2000). The most usual practice for measuring innovation outcomes is to consider a period of 3 or 5 years (OECD, 1992), from the moment when applied research is carried out until an incremental innovation outcome is achieved. Thus, in this step, a period of 3 years is used to test our model. This must be highlighted because it is a critical methodological issue due to the lack of updated accounting information. Future research using this model might consider a longer period of time up to 5 or more years. Nevertheless, findings could be arguable if such a longer period is considered, due to the effect of changes in the meantime that could invalidate the cause-effect link. Thus, perhaps a three year is the optimal option for measuring the medium-term effect. In this case, cumulative growth is calculated in the period from 2003 to 2006.

Sales growth reflects the market acceptance of a company’s products and thus is an indicator of success in its expansion through innovation (Zahra & Das, 1993: page 25; Zahra & Bogner, 1999: page 156). Value added or value aggregate (VA) is an indicator of compliance with financial objectives (Chen et al., 2004). In economic terms, VA is an accurate indicator of a company’s ability to generate additional value for some external inputs (Edvinsson & Malone, 1997; Marr et al., 2003). VA can be also used for measuring the performance of the global activities of an enterprise (Bontis, 2001). It is commonly defined as the difference between offered products and the cost of goods and services transferred from other external companies.

The value added by an organisation is one of the most important indicators at present, taking into account the general socioeconomic crisis since 2008 on. In the IC discourse, the value of a company (market value) is considered as a combination of tangible accounting value coming mainly from traditional forms of capital, such as physical and monetary capital and intangible value, the IC that comes from HC, SC and RC.

This section describes the methodology for sampling, data collection, their analysis, and the procedures for testing the proposed model in a sample of SMEs in Galicia (a region of Spain).

Sampling procedure and data collection

Economic and financial information was taken directly from the SABI database, which contains comprehensive official information on companies in Spain.

Statistical information about IC corresponds to a representative sample of 140 SMEs in Galicia (see Table 5) that were considered as innovative firms in 2003. Full information was available on their turnover and value added from 2003 to 2006 in the official Commercial Register (accessible through the SABI database).

40.447 SMEs, active in the autonomous region of Galicia, Spain (2003 data) and with economic data at SABI´s database

Women-owned family businesses in transitional economies: key influences on firm innovativeness and sustainability

Abstract

This research presents an examination of familial influence on strategic entrepreneurial behaviors within a transitional economic context. Utilizing a large sample of women-led family businesses, the study investigates the relationships between risk-taking propensity, entrepreneurial intensity, and opportunity recognition of the entrepreneur and the innovative orientation of the firm and sustainability. A model of the influences on innovativeness and sustainability in family firms is developed, and the potential contribution of the present study is the identification of constructs that facilitate these strategic outcomes and behaviors that drive growth. The degree to which family firms can create new products, services, and processes that add value to their marketplace can strongly influence their sustainability, especially in an emerging economy.

Background

Research conducted within the transitional economies of Central and Eastern Europe has shown that models of entrepreneurship have high transferability to these cultures (Gibb 1993; Gundry and Ben-Yoseph 1998; Kickul et al. 2010). Entrepreneurial firms are at the forefront of economic development in emerging economies (Neace 1999); as such, the influences on the growth and sustainability of these enterprises are of research and public policy interest. Numerous studies identifying the success factors of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) have been conducted in developed countries (Anna et al. 2000; Chaganti and Parasuraman 1997; Lerner and Almor 2002). However, more research utilizing rigorous scientific approaches is needed (Tkachev and Kolvereid 1999).

The study on women entrepreneurs and women in family firms can trace their start to the mid-1980s (Carsrud and Olm 1986; Hagan et al. 1989; Chrisman et al. 1990). Since that time, there has been an increasing interest in women entrepreneurs and the challenges they faced in developed economies (Marlow 1997; Carter and Allen 1997; Baker et al. 1997; Berg 1997; Cole 1997). The presence of women leading small and entrepreneurial organizations has had a powerful impact on the global business landscape and employment (Minnitti et al. 2005; Diana Project 2005). However, research on women entrepreneurs in transitional economies is less developed (Tkachev and Kolvereid 1999), and the positive impact of female entrepreneurs is not always recognized to the same degree by countries in transition (Welter and Smallbone 2010). Scholars have acknowledged that with regard to gender and entrepreneurship, policymakers and financial experts in any particular country should not uncritically rely on research results from other countries (Eriksson et al. 2009; Welter 2011). Bruton et al. (2008) pointed out a need to develop a deeper understanding of entrepreneurship in emerging economies. Furthermore, the lack of information on successful female entrepreneurs, especially running family firms, is especially apparent.

The study extends previous work by using a large sample of women-led family businesses in order to examine familial influence on strategic entrepreneurial behaviors, including opportunity recognition and innovativeness. This study examines whether family influence affects the relationships between risk-taking propensity, entrepreneurial intensity, and opportunity recognition of the entrepreneur and the innovative orientation of the firm and sustainability. The degree to which family firms can create new products, services, and processes that add value to their marketplace can strongly influence their sustainability, especially in an emerging economy.

This paper is structured as follows: first, we discuss family firms in entrepreneurship research and the usage of family and gender as explanatory variables. Next, family business research within transitional economies is discussed, with focus on the Russian context. The theoretical constructs employed in this research are summarized, and the research model is presented. The ‘Methods’ section with description of the sample, research instrument, and operationalization of the constructs is followed by results of the analysis and discussion, and implications for future scholarship and practice in this area.

Family firms and entrepreneurial research

The academic study on family business is usually tied to the founding of Family Business Review in 1987 (Carsrud and Brännback 2012). The characteristics, capabilities, and resources of family firms can influence entrepreneurial orientation, including innovation and risk-taking behaviors (Zahra 2005), making family firms an excellent context in which to examine entrepreneurial processes (Zahra et al. 2004; Dyer 2006; Naldi et al. 2007; Nordqvist et al. 2008). Furthermore, as noted by Naldi et al. (2007), more research is needed on the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and firm outcomes within family firms.

Research on family firms also has tended to focus on male founders and successors (Hall et al. 2001; Steier 2001), while many other topics have been largely ignored (Carsrud and Brännback 2012). Perricone et al. (2001) have shown that most successors are first-born males. However, the empirical study on leadership in family firms remains largely understudied (Renko et al. 2012). Family business research continues to lack unified theories (Carsrud and Brännback 2012) but is still identified by a few key themes such as succession, intergenerational conflict, growth, and corporate and family governance (Miller and Le Breton-Miller 2003; Sonfield and Lussier 2004; Carsrud and Brännback 2012). The field of family business cannot even agree on a definition of what constitutes a family business or even a family (Carsrud et al. 1996; Chrisman et al. 1996; Chua et al. 1999; Carsrud 2006; Carsrud and Brännback 2012). If the study on women entrepreneurs and women in family businesses is to advance, more empirical research needs to be done based on both existing research and well-tested theories that can work across genders and using objective and measurable operational definitions of concepts.

Using family and gender as explanatory variables

To understand family as an explanatory factor in entrepreneurial family firms in transitional economies requires looking at the relationship between two systems (family and firm). Here is where the concept of family influence (Habbershon et al. 2003) can provide both a theoretical basis and research evidence. This concept can be of use in understanding women-led family firms and the attractiveness of such firms in terms of social, human, and financial capital (Carter and Rosa 1998). While such an approach has its merits, it still suffers from the attempt to turn essentially a loosely defined demographic variable (family) into a causal factor. Is family really a unitary concept or is it in fact a multi-faceted term that serves as a quick reference for a variety of factors such as generations, values, religion, ethnicity, culture, etc.? In other words, when one uses the term family, one is subsuming a number of factors within that term. Is the impact of family or family influence due to values, cultural background, organizational structure, the number of family members in the firm, who leads it, or the number of generations involved (Carsrud and Brännback 2012)? To advance social science, one needs to add precision to the definition of family influence and family as they are most likely multi-dimensional variables for purposes of research studies. The current study is limited to the definition provided by the subjects’ self-reports. While this may limit the generalizations and explanations available from the current study, if individuals self-identify as a family firm, then one can assume they perceive family to be an important influence, or identity, in the firm.

Family context may have a special importance for women entrepreneurs. Recent literature suggests that for women, work-life balance is a more complex and demanding task, involving family embeddedness as the main issue (Brush et al. 2009). Jennings and McDougal (2007) suggested the term ‘motherhood’ as a metaphor representing the household/family context. Brush et al. (2009) argued that motherhood or family/household contexts might have a larger impact on women than men, while Welter and Smallbone (2010) illustrated that this context might be very different depending on the country of operation. For example, in a recent study of entrepreneurial intentions in two developed and two developing countries, it was found that the highest barrier for starting a business is indeed risk related (Iakovleva et al. 2013). However, that was not the case for developing countries, where risk barrier was ranked second or third. It was concluded that in more turbulent environments, people generally rely less on government or existing jobs. Thus, risk relating to owning and running a business is perceived lower in comparison with developed countries, where being an employee provides far more benefits and security. In their study of Russian and Ukrainian women entrepreneurs, (Iakovleva et al., unpublished work) found that developing countries often do not provide the same institutional conditions for working women during their maternity leave. This reduces the benefits of being employed in relation to running a business, which provides more flexibility. This might have direct implications for the models explain behavior of family-owned firms as well, where it is often suggested that such firms are less risk oriented based on the results of empirical findings from developed countries. Thus, in the present study, we suggest using gender as a lens to explore behavior of female entrepreneurs in family-owned firms.

Family business research in transitional economies

Entrepreneurship in the Russian context

Entrepreneurs in a transitioning economy may face continuing challenges and obstacles, including unpredictable and often hostile external environments, and resource scarcity, especially financial resources (Smallbone and Welter 2001). Research on entrepreneurship in transition economies over the last two decades has included research on start-ups in Poland (Erutku and Vallée 1997), venture capital in Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia (Karsai et al. 1998), as well as studies on the growth of women-owned firms in Turkey (Esim 2000; Hisrich and Ozturk 1999) and entrepreneurs in India (Mitra 2002).

In comparison to other transition economies such as India and China, the development of the small business sector in Russia has been somewhat slower (Verkhovskaya et al. 2007). For example, the number of SMEs per 10,000 inhabitants is 6.0 in Russia (Zhuplev 2009). By comparison, in the EU, there are approximately 30 registered SMEs per 10,000 inhabitants.

In part, this is explained by the operating environment for entrepreneurs and small businesses that can involve extensive bureaucracy, corruption, weakly developed financial markets, and poor governmental support mechanisms for beginning entrepreneurs (Karhunen et al. 2008; Verkhovskaya et al. 2007). In addition, poor management, a lack of knowledge and experience, and the culture of market relations hinder the development of entrepreneurship (Kickul et al. 2010; Iakovleva et al., unpublished work). Russia’s transition from a centrally planned to a market economy began in the early 1990s (Ogloblin 1999). Twenty-plus years later, SMEs in Russia are a key part of the country’s sustainable economic development. SMEs constitute 20-25% share in GSP with high growth potential forecasted (European Investment Bank, 2013).

During the past decade, positive changes in relation to entrepreneurship support systems and funding opportunities have been observed in Russia. In recent Russian banking history, there were two periods when banks targeted SMEs and entrepreneurs. The first period was in the late 1990s, when the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development mostly granted credit to micro and small businesses. However, in 2000 this program was closed. Nearly 10 years later a new wave targeting small business began, and today banks offer a wide range of services, including loans, for the SME sector. However, the interest rate for loans is quite high, and many start-ups chose to use other, informal, sources of funding (Iakovleva et al. 2013). Although few in number, there are programs to support entrepreneurs with venture capital, mortgages, or business incubation. One example is non-repayable subsidies of 300,000 RUB (approximately equivalent to 7,000 euros) to start a business. For SMEs at the development stage, there is, for example, a special program to cover the first lease payment or leasing interest for those who need equipment. To support innovation, there are programs covering patent payments, certification, or R&D costs. There are also programs at the federal level intended to promote a positive image of entrepreneurship. For a country with no tradition of entrepreneurship, it is important that people understand that business owners create work places, attract investment, and pay tax. However, there is an absence of any programs or initiatives to promote women entrepreneurs in Russia. Also, when it comes to funding availability, banks do not differentiate on gender; rather, the payment history and general business conditions are estimated (Iakovleva et al. 2013).

Most Russian entrepreneurs are between 30 to 50 years of age (Wells et al. 2003; Turen 1993); 70% to 80% have higher levels of education (Babaeva 1998; Wells et al. 2003). Women entrepreneurs in Russia have yet to follow worldwide trends similar to those found in other national studies on women entrepreneurs. By various estimates, the enterprises managed by women provide 50% to 52% of the national GDP in Germany and in the USA, 52% to 55% in Japan, and 57% to 60% in Italy (Gorbulina 2006), suggesting that women in these countries are fairly well integrated in economic development. However, in Russia it is estimated that women entrepreneurs only represent 30% to 40% of the total. According to Ylinenpåå and Chechurina (2000), societal limitations in other fields may ultimately serve as factors propelling women to enter the entrepreneurial sector, where starting new ventures serves the dual purpose of generating additional family income and increasing self-fulfillment. However, it is clear that they have yet to achieve the percentages found in more developed economies.

In the current market economy, those women entrepreneurs have adapted and sought to acquire knowledge and information rapidly. As noted above, Russian women generally have a high level of education and many possess more than one degree from institutions of higher education. This characteristic, along with the ability to establish relationships, leads to steadier levels of employment and higher income generation in women-owned companies (Gorbulina, 2006). First-generation Russian women entrepreneurs succeeded in a highly dynamic environment in the transition to the market economy. As economic conditions stabilize, new opportunities are emerging for women (Kickul et al, 2010).

Since entrepreneurial businesses first emerged following the fall of the Soviet Union, first-generation Russian women entrepreneurs have succeeded in a highly dynamic environment in the transition to the market economy. As economic conditions stabilize and new opportunities emerge for these entrepreneurs, the ability of firms to survive and grow requires an entrepreneurial orientation. The present study expands previous work to propose a theoretically driven model exploring the role of entrepreneurial orientation in the innovation and sustainability of women-led family firms in a transitional economy.

Entrepreneurial orientation in family firms: the roles of risk taking, entrepreneurial intensity, and recognizing new opportunities for innovation

Organizations that exhibit an entrepreneurial orientation tend to engage in risk-taking behavior, including incurring debt and making large resource commitments with the expectation of high return (Lumpkin and Dess 1996). Casillas and Moreno (2010) studied the influence of family involvement on entrepreneurial orientation and growth, and results showed that family involvement increases the influence of innovativeness on growth and, at the same time, decreases the influence of risk taking on growth. In the family business context, researchers have found that family firms are less inclined to undertake risk, perhaps because the survival of the firm is of utmost importance; this seems to be especially true in emerging and underdeveloped economies (Zahra 2005; Gomez-Mejia et al. 2007).

Opportunity recognition in the context of family firms

The motivation of the entrepreneur has been shown as an important factor associated with superior firm performance (Carsrud et al. 1989; Carsrud and Brännback 2011); static personality characteristics and other individual traits have not been proven less effective at predicting performance (Sandberg and Hofer 1987). The ability to identify opportunities is very valuable for entrepreneurs as they are able to recognize and develop market opportunities, strengthening the competitive advantage of their firms (Chandler and Hanks 1994; Carsrud and Brannback 2007). Opportunity identification involves identifying new market opportunities for products and services, discovering new ways of improving existing products, and forecasting customers’ unmet needs (De Noble et al. 1999). Opportunity recognition is a process of perceiving a possibility to create a new business or to significantly improve the position of an existing business, and in both cases, new profit potential emerges (Christensen et al. 1994).

Similarly, innovativeness is perceived as a highly relevant component of entrepreneurial orientation in the family firm context (Nordqvist et al. 2008; Zellweger and Sieger 2012). Innovation can be defined as the effective application of new products and processes designed to benefit the organization and its stakeholders (West and Anderson 1996; Wong et al. 2009). According to Damanpour (1996), innovation is a means of transforming an organization in response to changes in the external environment or, proactively, to influence the environment. Based on a multidisciplinary analysis, scholars recently proposed an integrative definition of innovation as a multistage process in which firms transform ideas into new or improved products, services, or processes to compete and differentiate themselves in the marketplace (Baregheh et al. 2009).

Researchers have postulated that family firms tend to have a longer-term orientation and, thus, may have well-developed entrepreneurial strategies for innovation, especially if the entrepreneur has a strong orientation towards innovativeness and can make decisions more rapidly given the structure of the family firm (James 1999; Mustakallio and Autio 2002; Zahra et al. 2004; Casillas and Moreno 2010). Entrepreneurial innovativeness can be directed towards achieving specific firm outcomes, including sustainability. Given the general long-term orientation of family firms, it is of research interest to investigate the influences of entrepreneurial orientation and firm innovativeness on the sustainability of a family-led organization.

Sustainability

Sustainability is often described as a measure of an organization’s ability to fulfill its mission and serve its stakeholders over a longer period of time and to have a recognizable and measurable impact. Improved sustainability can lead to broader sources of funding and enhances the firm’s ability to provide value over an extended period of time (Bryson 2004; Carsrud and Brännback 2010). The process of achieving sustainability is designed to achieve specific, identifiable goals toward a specific impact and not an end into itself. Sustainability involves all the elements and functions of an organization and every major decision made within the organization (Chen and Singh 1995; Bryson 2004; Carsrud and Brännback 2010). Sustainability has been characterized by capacity and adaptability (York 2012). There are four components of a sustainable firm: (1) the adaptive capacity to monitor, assess, and respond to both internal and external changes; (2) the leadership capacity to make decisions and to provide the direction necessary to achieve the organization’s goals; (3) the management capacity to employ resources efficiently and, typically, in a resource-constrained environment, and (4) the technical capacity (skills, experience, and knowledge) needed to implement the programmatic, organizational, and community strategies (Bryson 2004; Carsrud and Brännback 2010; York 2012).

A firm’s focus on sustainability leads to a greater emphasis on long-term viability and impact, and it relies on an approach to innovation that effectively applies new processes in ways that benefit the stakeholders of the organization (West and Anderson 1996; Wong et al. 2009). By introducing innovative processes and practices, sustainable organizations are able to adapt to challenging scenarios and can operate in resource-constrained environments (Carsrud and Brännback 2010).

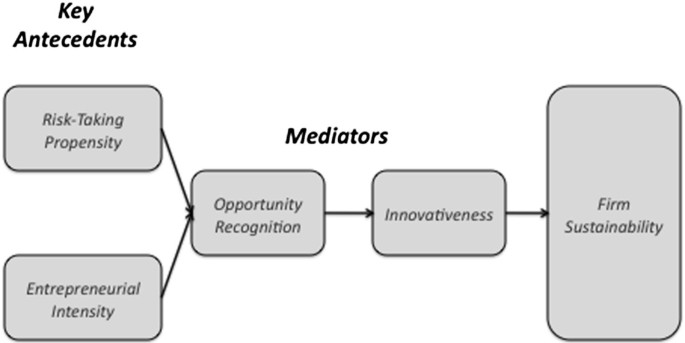

Research model

The present study focuses on a large sample (N = 310) of Russian female entrepreneurs heading family firms. Previous research indicates that Russian women often attribute their entrance into entrepreneurship to ‘push’ factors, such as the need to generate family income and create an arena for self-fulfillment (Minnitti et al. 2005; Reynolds and White 1997), and they are able to identify growth opportunities (Iakovleva and Kickul 2007). Although some of the findings in the literature discussed above regarding growth orientation and innovativeness of family firms are sometimes contradictory, we suggest that the turbulent environment of the Russian economy provides stimulus for women entrepreneurs to perform opportunity-oriented behavior. Previous research has shown that risk taking, among other proactive behaviors, and innovativeness influence growth in family firms (Casillas and Moreno 2010). Based on the above discussion, risk-taking propensity and entrepreneurial intensity leading to opportunity recognition are important antecedents of innovativeness which in turn is seen as key to obtaining firm sustainability. The following research model is proposed (Figure 1).

Model for influences on innovativeness and sustainability in family firms.

A potential contribution of the present study is the identification of constructs that facilitate innovativeness and firm sustainability in these family businesses. These are depicted in the model below. This approach may help practitioners and policy makers formulate and implement new strategies and programs supporting women entrepreneurs. These findings are especially important to the discovery of ways to support female-led family businesses within turbulent transition economies as they innovate and achieve sustainable business performance.

Results

Unlike much previous research on family firms which typically show reduced levels of risk taking, the current findings revealed that Russian female entrepreneurs within family firms exhibited both risk-taking attitudes and an entrepreneurial intensity. These then led them to seek and find new opportunities and implement these opportunities and innovations for the marketplace. It is possible that the current research is reflecting the early stage of these ventures, but it does challenge the notion that family firms are less risk oriented. The findings revealed that both opportunity recognition and innovativeness fully mediated the relationship between risk taking and entrepreneurial intensity and firm sustainability, that is, these key antecedents leading to venture sustainability of a venture were consistently structured, valued, and in place for these women-led family firms.

Discussion

While this study clearly needs to be replicated with other samples of female entrepreneurs running family-owned firms within emerging economies, this study has allowed a view into what drives sustainability and growth in new family firms run by women in an emerging economy. It is certainly possible that the cultural context in this study, Russia, does have an impact on the risk taking being displayed and subsequent impact on opportunity recognition and innovation. For example, a culture that does not prize innovation may therefore not see this as important behaviors to exhibit even if it is important to subsequent entrepreneurial performance and firm sustainability. The Russian culture has certainly prized education and scientific innovation; therefore, one would expect that risk-taking attitudes would be found to impact firms via innovation, given the cultural support for such behaviors.

It is interesting to explore the extent to which our results correlate with findings from other research. Although Hofstede’s measures of uncertainty avoidance are quite high for Russia with a value of 95 compared to the average of 50 for developed countries (Hofstede 2001), other research asserts that Iakovleva this general measure does not indeed reflect risk in relation to establishing or operating a business. In fact, it was found that start-up intentions are higher in developing countries (Iakovleva et al. 2011) and that risk is perceived as a higher barrier in developed countries (Iakovleva et al., unpublished work)). Thus, although Russia is relatively low with regard to the measurement of total entrepreneurial activity a (TEA = 4.6) in comparison to an average of 14.1 for factor-driven economies (Bosma et al. 2011), risk is perceived as a less important barrier in comparison to financing (Iakovleva et al., unpublished work). Our findings from the present research confirm positive propensity toward risk taking among Russian family businesses.

This paper adds to the literature on the impact of cognitive/psychological factors of entrepreneurs. It shows that the impact is not direct as many early researchers proposed and yet were unable to demonstrate (Sandberg and Hofer 1987), but in fact operate as indirect influences on firm performance as proposed by Carsrud et al. (1989) and Carsrud and Brännback (2011). This shows that risk taking and intensity are critical to subsequent opportunity recognition and innovation. Those factors in turn are critical to firm sustainability. The implications of this research suggest that entrepreneurs can be encouraged to undertake appropriate risks, even in environments where obstacles exist, as a means to embrace opportunities in the marketplace. If they do so effectively, they contribute to the sustainability of their organizations. More work is needed here to promote the development of entrepreneurial instruction and support programmes towards this goal, helping entrepreneurs identify and pursue objectives critical to sustainability of their ventures.

This paper adds to both our understanding on family-owned firms and family firms owned and managed by women. It is clear that in the Russian context of the early twenty-first century, such firms’ sustainability is impacted by the risk-taking attitudes and entrepreneurial intensity of their women leaders. This may be due to the nature of that particular emerging economy, as these findings support the recent comparison between developing and developed countries (Bosma et al. 2011; Iakovleva et al. 2011). However, our findings also suggest that in newer family firms run by women, opportunity recognition and innovation are critical to survival and growth. A recent study on Russian female entrepreneurs suggests that they often need to be very competitive and make bold decisions, and the challenge of being women in a turbulent environment adds to the necessity for taking calculated risks (Iakovleva et al. 2013). The present study shows that Russian women are very capable of exhibiting those behaviors in order to sustain their self-identified family firms. The traditional myth of risk aversion often seen in more established economies and firms may not hold in emerging economies, with family firms headed by women. This is an example of the kinds of myths and assumptions that family business researchers need to challenge and which can only be done by looking beyond the traditional samples in Western developed economies with large established family firms (Carsrud and Brännback 2012).

Conclusions

The ever evolving competitive environments in transitional economies render seemingly sustainable strategic advantages obsolete. Instead, competitive advantages arise from a family firm’s capability to constantly redeploy, reconfigure, rejuvenate, and innovate their capabilities in responding to the changing environmental conditions.

Methods

Participants were entrepreneurs of 310 Russian women-led family firms. The data were obtained from the Russian Women’s Micro-financial Network (RWMN). The mission of the RWMN is to support the development of sustainable women-focused, locally managed microfinance institutions (MFIs) throughout Russia by creating an effective financial and technical structure that provides high-quality services to partner MFIs over the long term. RWMN operates in six regions in Russia: Kostroma, Tver, Kaluga, Belgorod, Vidnoe, and Tula, with the head office in Moscow. Each division is an independent local organization that provides micro loans for clients, with no less than 51% of clients being women.

The survey was pretested with the assistance of seven native-speaking Russian women entrepreneurs who commented on each question. Data were collected by the workers of local divisions during face-to-face interviews with respondents. Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 3. The sample mainly consists of sole proprietorships with 94% of businesses having no more than ten employees (and 60% having just two employees), being woman-led and woman-owned (95%), operating mainly in the service industry (80%), with 56% of the enterprises self-reporting as being family businesses. This profile differs from the typical Russian SME profile with regard to gender, educational background, industry structure, legal form, number of employees, and family business issues (Iakovleva 2005; Bezgodov 1999). One might consider these as early-stage, small family firms.