Git how to undo commit

Git how to undo commit

How to undo (almost) anything with Git

One of the most useful features of any version control system is the ability to «undo» your mistakes. In Git, «undo» can mean many slightly different things.

One of the most useful features of any version control system is the ability to “undo” your mistakes. In Git, “undo” can mean many slightly different things.

When you make a new commit, Git stores a snapshot of your repository at that specific moment in time; later, you can use Git to go back to an earlier version of your project.

In this post, I’m going to take a look at some common scenarios where you might want to “undo” a change you’ve made and the best way to do it using Git.

Undo a “public” change

Undo with: git revert

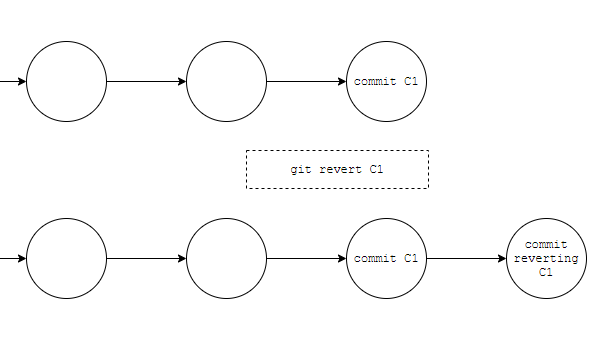

What’s happening: git revert will create a new commit that’s the opposite (or inverse) of the given SHA. If the old commit is “matter”, the new commit is “anti-matter”—anything removed in the old commit will be added in the new commit and anything added in the old commit will be removed in the new commit.

This is Git’s safest, most basic “undo” scenario, because it doesn’t alter history—so you can now git push the new “inverse” commit to undo your mistaken commit.

Fix the last commit message

Undo “local” changes

Scenario: The cat walked across the keyboard and somehow saved the changes, then crashed the editor. You haven’t committed those changes, though. You want to undo everything in that file—just go back to the way it looked in the last commit.

Keep in mind: any changes you “undo” this way are really gone. They were never committed, so Git can’t help us recover them later. Be sure you know what you’re throwing away here! (Maybe use git diff to confirm.)

Reset “local” changes

Scenario: You’ve made some commits locally (not yet pushed), but everything is terrible, you want to undo the last three commits—like they never happened.

Redo after undo “local”

Undo with: git reflog and git reset or git checkout

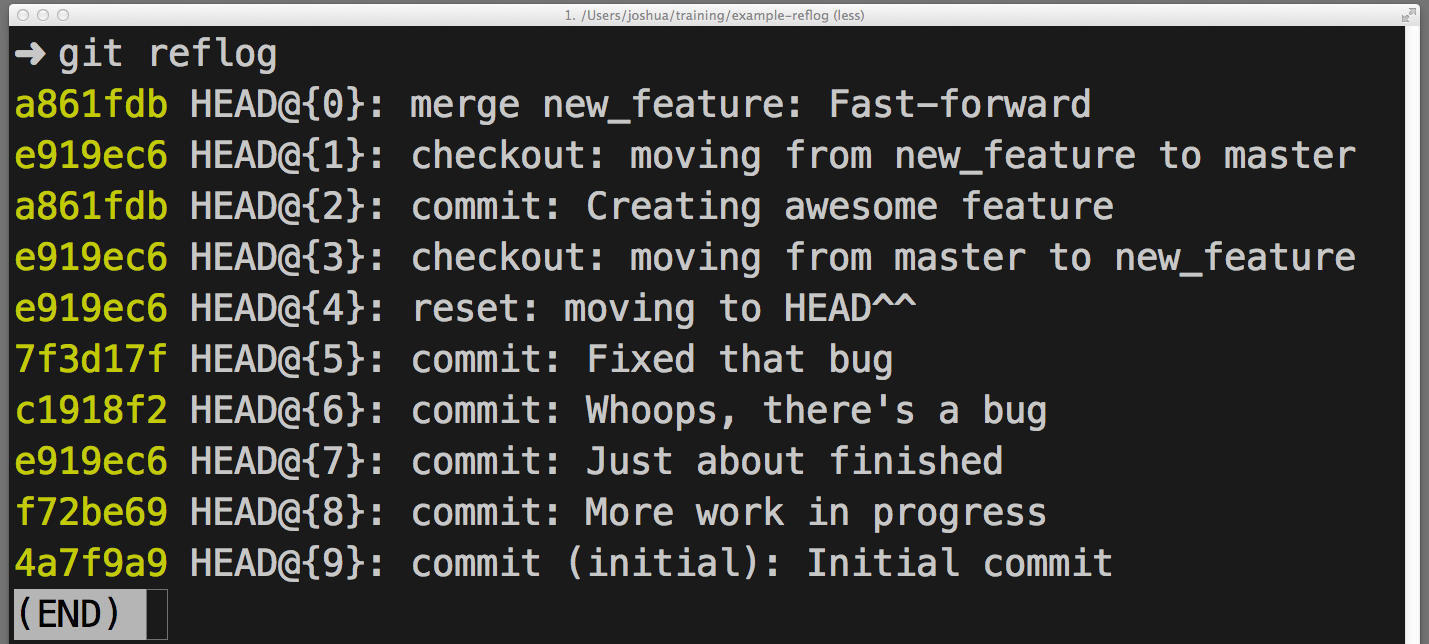

What’s happening: git reflog is an amazing resource for recovering project history. You can recover almost anything—anything you’ve committed—via the reflog.

You’re probably familiar with the git log command, which shows a list of commits. git reflog is similar, but instead shows a list of times when HEAD changed.

So… how do you use the reflog to “redo” a previously “undone” commit or commits? It depends on what exactly you want to accomplish:

Once more, with branching

Finally, git checkout switches to the new feature branch, with all of your recent work intact.

Branch in time saves nine

Undo with: git checkout feature and git rebase master

git rebase master does a couple of things:

Mass undo/redo

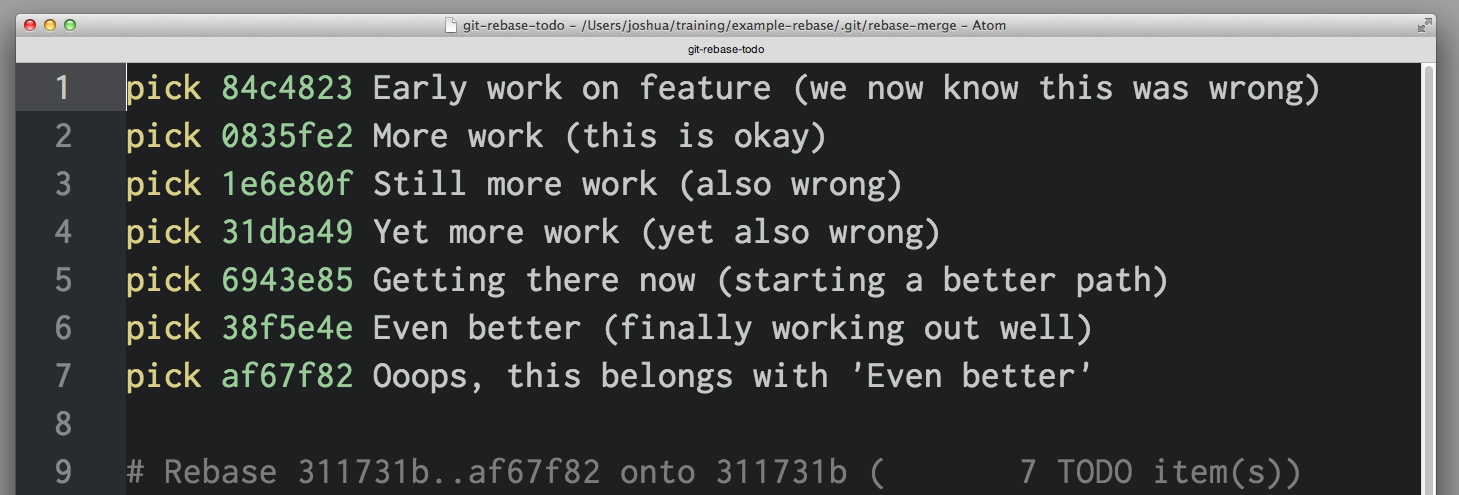

Scenario: You started this feature in one direction, but mid-way through, you realized another solution was better. You’ve got a dozen or so commits, but you only want some of them. You’d like the others to just disappear.

To drop a commit, just delete that line in your editor. If you no longer want the bad commits in your project, you can delete lines 1 and 3-4 above.

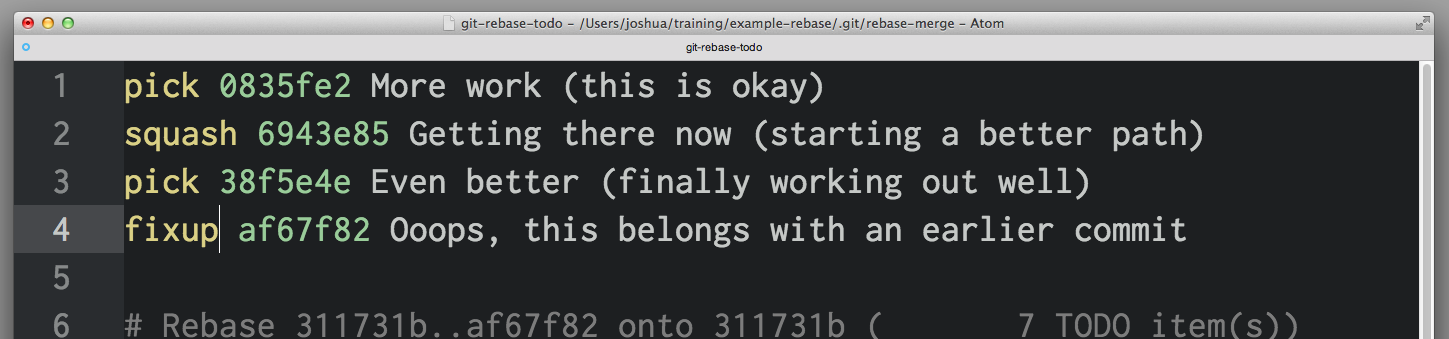

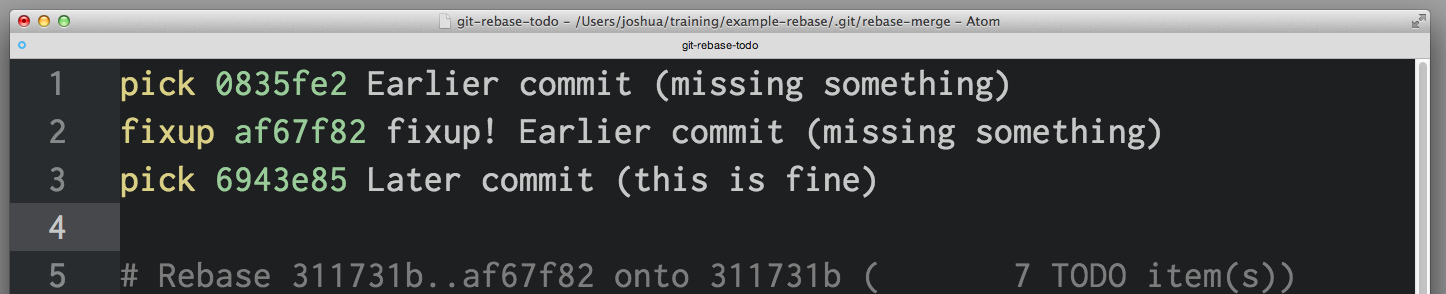

If you want to combine two commits together, you can use the squash or fixup commands, like this:

squash and fixup combine “up”—the commit with the “combine” command will be merged into the commit immediately before it. In this scenario, 0835fe2 and 6943e85 will be combined into one commit, then 38f5e4e and af67f82 will be combined together into another.

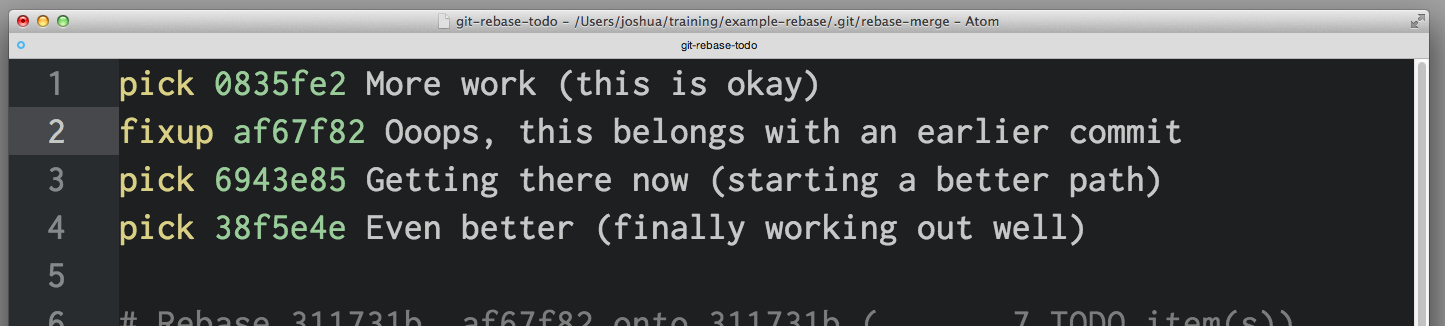

When you save and exit your editor, Git will apply your commits in order from top to bottom. You can alter the order commits apply by changing the order of commits before saving. If you’d wanted, you could have combined af67f82 with 0835fe2 by arranging things like this:

Fix an earlier commit

4 is four commits before HEAD – or, altogether, five commits back.

Stop tracking a tracked file

That’s how to undo anything with Git. To learn more about any of the Git commands used here, check out the relevant documentation:

Undoing Things

At any stage, you may want to undo something. Here, we’ll review a few basic tools for undoing changes that you’ve made. Be careful, because you can’t always undo some of these undos. This is one of the few areas in Git where you may lose some work if you do it wrong.

This command takes your staging area and uses it for the commit. If you’ve made no changes since your last commit (for instance, you run this command immediately after your previous commit), then your snapshot will look exactly the same, and all you’ll change is your commit message.

The same commit-message editor fires up, but it already contains the message of your previous commit. You can edit the message the same as always, but it overwrites your previous commit.

As an example, if you commit and then realize you forgot to stage the changes in a file you wanted to add to this commit, you can do something like this:

You end up with a single commit — the second commit replaces the results of the first.

It’s important to understand that when you’re amending your last commit, you’re not so much fixing it as replacing it entirely with a new, improved commit that pushes the old commit out of the way and puts the new commit in its place. Effectively, it’s as if the previous commit never happened, and it won’t show up in your repository history.

The obvious value to amending commits is to make minor improvements to your last commit, without cluttering your repository history with commit messages of the form, “Oops, forgot to add a file” or “Darn, fixing a typo in last commit”.

Only amend commits that are still local and have not been pushed somewhere. Amending previously pushed commits and force pushing the branch will cause problems for your collaborators. For more on what happens when you do this and how to recover if you’re on the receiving end read The Perils of Rebasing.

Unstaging a Staged File

The next two sections demonstrate how to work with your staging area and working directory changes. The nice part is that the command you use to determine the state of those two areas also reminds you how to undo changes to them. For example, let’s say you’ve changed two files and want to commit them as two separate changes, but you accidentally type git add * and stage them both. How can you unstage one of the two? The git status command reminds you:

Right below the “Changes to be committed” text, it says use git reset HEAD … to unstage. So, let’s use that advice to unstage the CONTRIBUTING.md file:

The command is a bit strange, but it works. The CONTRIBUTING.md file is modified but once again unstaged.

For now this magic invocation is all you need to know about the git reset command. We’ll go into much more detail about what reset does and how to master it to do really interesting things in Reset Demystified.

Unmodifying a Modified File

What if you realize that you don’t want to keep your changes to the CONTRIBUTING.md file? How can you easily unmodify it — revert it back to what it looked like when you last committed (or initially cloned, or however you got it into your working directory)? Luckily, git status tells you how to do that, too. In the last example output, the unstaged area looks like this:

It tells you pretty explicitly how to discard the changes you’ve made. Let’s do what it says:

You can see that the changes have been reverted.

If you would like to keep the changes you’ve made to that file but still need to get it out of the way for now, we’ll go over stashing and branching in Git Branching; these are generally better ways to go.

Undoing things with git restore

Unstaging a Staged File with git restore

The CONTRIBUTING.md file is modified but once again unstaged.

Unmodifying a Modified File with git restore

What if you realize that you don’t want to keep your changes to the CONTRIBUTING.md file? How can you easily unmodify it — revert it back to what it looked like when you last committed (or initially cloned, or however you got it into your working directory)? Luckily, git status tells you how to do that, too. In the last example output, the unstaged area looks like this:

It tells you pretty explicitly how to discard the changes you’ve made. Let’s do what it says:

It’s important to understand that git restore is a dangerous command. Any local changes you made to that file are gone — Git just replaced that file with the last staged or committed version. Don’t ever use this command unless you absolutely know that you don’t want those unsaved local changes.

Undoing Commits & Changes

In this section, we will discuss the available ‘undo’ Git strategies and commands. It is first important to note that Git does not have a traditional ‘undo’ system like those found in a word processing application. It will be beneficial to refrain from mapping Git operations to any traditional ‘undo’ mental model. Additionally, Git has its own nomenclature for ‘undo’ operations that it is best to leverage in a discussion. This nomenclature includes terms like reset, revert, checkout, clean, and more.

A fun metaphor is to think of Git as a timeline management utility. Commits are snapshots of a point in time or points of interest along the timeline of a project’s history. Additionally, multiple timelines can be managed through the use of branches. When ‘undoing’ in Git, you are usually moving back in time, or to another timeline where mistakes didn’t happen.

This tutorial provides all of the necessary skills to work with previous revisions of a software project. First, it shows you how to explore old commits, then it explains the difference between reverting public commits in the project history vs. resetting unpublished changes on your local machine.

Finding what is lost: Reviewing old commits

The whole idea behind any version control system is to store “safe” copies of a project so that you never have to worry about irreparably breaking your code base. Once you’ve built up a project history of commits, you can review and revisit any commit in the history. One of the best utilities for reviewing the history of a Git repository is the git log command. In the example below, we use git log to get a list of the latest commits to a popular open-source graphics library.

When you have found a commit reference to the point in history you want to visit, you can utilize the git checkout command to visit that commit. Git checkout is an easy way to “load” any of these saved snapshots onto your development machine. During the normal course of development, the HEAD usually points to main or some other local branch, but when you check out a previous commit, HEAD no longer points to a branch—it points directly to a commit. This is called a “detached HEAD ” state, and it can be visualized as the following:

Checking out an old file does not move the HEAD pointer. It remains on the same branch and same commit, avoiding a ‘detached head’ state. You can then commit the old version of the file in a new snapshot as you would any other changes. So, in effect, this usage of git checkout on a file, serves as a way to revert back to an old version of an individual file. For more information on these two modes visit the git checkout page

Viewing an old revision

This example assumes that you’ve started developing a crazy experiment, but you’re not sure if you want to keep it or not. To help you decide, you want to take a look at the state of the project before you started your experiment. First, you’ll need to find the ID of the revision you want to see.

Let’s say your project history looks something like the following:

You can use git checkout to view the “Make some import changes to hello.txt” commit as follows:

This makes your working directory match the exact state of the a1e8fb5 commit. You can look at files, compile the project, run tests, and even edit files without worrying about losing the current state of the project. Nothing you do in here will be saved in your repository. To continue developing, you need to get back to the “current” state of your project:

This assumes that you’re developing on the default main branch. Once you’re back in the main branch, you can use either git revert or git reset to undo any undesired changes.

Undoing a committed snapshot

There are technically several different strategies to ‘undo’ a commit. The following examples will assume we have a commit history that looks like:

We will focus on undoing the 872fa7e Try something crazy commit. Maybe things got a little too crazy.

How to undo a commit with git checkout

Using the git checkout command we can checkout the previous commit, a1e8fb5, putting the repository in a state before the crazy commit happened. Checking out a specific commit will put the repo in a «detached HEAD » state. This means you are no longer working on any branch. In a detached state, any new commits you make will be orphaned when you change branches back to an established branch. Orphaned commits are up for deletion by Git’s garbage collector. The garbage collector runs on a configured interval and permanently destroys orphaned commits. To prevent orphaned commits from being garbage collected, we need to ensure we are on a branch.

How to undo a public commit with git revert

How to undo a commit with git reset

The log output shows the e2f9a78 and 872fa7e commits no longer exist in the commit history. At this point, we can continue working and creating new commits as if the ‘crazy’ commits never happened. This method of undoing changes has the cleanest effect on history. Doing a reset is great for local changes however it adds complications when working with a shared remote repository. If we have a shared remote repository that has the 872fa7e commit pushed to it, and we try to git push a branch where we have reset the history, Git will catch this and throw an error. Git will assume that the branch being pushed is not up to date because of it’s missing commits. In these scenarios, git revert should be the preferred undo method.

Undoing the last commit

Undoing uncommitted changes

Before changes are committed to the repository history, they live in the staging index and the working directory. You may need to undo changes within these two areas. The staging index and working directory are internal Git state management mechanisms. For more detailed information on how these two mechanisms operate, visit the git reset page which explores them in depth.

The working directory

The staging index

Undoing public changes

Summary

In addition to the primary undo commands, we took a look at other Git utilities: git log for finding lost commits git clean for undoing uncommitted changes git add for modifying the staging index.

Each of these commands has its own in-depth documentation. To learn more about a specific command mentioned here, visit the corresponding links.

Git Revert Commit – How to Undo the Last Commit

Say you’re working on your code in Git and something didn’t go as planned. So now you need to revert your last commit. How do you do it? Let’s find out!

There are two possible ways to undo your last commit. We’ll look at both of them in this article.

The revert command

The revert command will create a commit that reverts the changes of the commit being targeted. You can use it to revert the last commit like this:

The reset command

You can also use the reset command to undo your last commit. But be careful – it will change the commit history, so you should use it rarely. It will move the HEAD, the working branch, to the indicated commit, and discard anything after:

This will undo the latest commit, but also any uncommitted changes.

Should You Use reset or revert in Git?

You should really only use reset if the commit being reset only exists locally. This command changes the commit history and it might overwrite history that remote team members depend on.

revert instead creates a new commit that undoes the changes, so if the commit to revert has already been pushed to a shared repository, it is best to use revert as it doesn’t overwrite commit history.

Conclusion

You have learned two ways to undo the last commit and also when it’s best to use one over the other.

Now if you notice that your last commit introduces a bug or should have not been committed you know how to fix that!

Moderator and staff author for freeCodeCamp.

If you read this far, tweet to the author to show them you care. Tweet a thanks

Learn to code for free. freeCodeCamp’s open source curriculum has helped more than 40,000 people get jobs as developers. Get started

freeCodeCamp is a donor-supported tax-exempt 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization (United States Federal Tax Identification Number: 82-0779546)

Donations to freeCodeCamp go toward our education initiatives, and help pay for servers, services, and staff.

Git для начинающих. Часть 9. Как удалить коммит в git?

Рассмотрим довольно важный вопрос: как удалить коммит в git? Начнем с вопроса отмены изменений в рабочей директории, после этого перейдем к репозиторию. В рамках этой темы изучим вопросы удаления и замены последнего коммита, работу с отдельными файлами и использование команд git revert и git reset.

Отмена изменений в файлах в рабочей директории

Если вы сделали какие-то изменения в файле и хотите вернуть предыдущий вариант, то для этого следует обратиться к репозиторию и взять из него файл, с которым вы работаете. Таким образом, в вашу рабочую директорию будет скопирован файл из репозитория с заменой. Например, вы работаете с файлом main.c и внесли в него какие-то изменения. Для того чтобы вернуться к предыдущей версии (последней отправленной в репозиторий) воспользуйтесь командой git checkout.

Отмена коммитов в git

Работа с последним коммитом

Для демонстранции возможностей git создадим новый каталог и инициализируем в нем репозиторий.

Добавим в каталог файл main.c.

Отправим изменения в репозиторий.

Внесем изменения в файл.

И сделаем еще один коммит.

В репозиторий, на данный момент, было сделано два коммита.

Теперь удалим последний коммит и вместо него отправим другой. Предварительно изменим содержимое файла main.c.

Отправим изменения в репозиторий с заметой последнего коммита.

Как вы можете видеть: из репозитория пропал коммит с id=d142679, вместо него теперь коммит с id=18411fd.

Отмена изменений в файле в выбранном коммите

Сделаем ещё несколько изменений в нашем файле main.c, каждое из которых будет фиксироваться коммитом в репозиторий.

Помните, что в предыдущем разделе мы поменяли коммит с сообщением “second commit” на “third commit”, поэтому он идет сразу после “first commit”.

Представим ситуацию, что два последних коммита были неправильными, и нам нужно вернуться к версии 18411fd и внести изменения именно в нее. В нашем примере, мы работаем только с одним файлом, но в реальном проекте файлов будет много, и после коммитов, в рамках которых вы внесли изменения в интересующий вас файл, может быть ещё довольно много коммитов, фиксирующих изменения в других файлах. Просто так взять и удалить коммиты из середины ветки не получится – это нарушит связность, что идет в разрез с идеологией git. Одни из возможных вариантов – это получить версию файла из нужного нам коммита, внести в него изменения и сделать новый коммит. Для начала посмотрим на содержимое файла main.c из последнего, на текущий момент, коммита.

Для просмотра содержимого файла в коммите с id=18411fd воспользуемся правилами работы с tree-ish (об этом подробно написано здесь)

Переместим в рабочую директорию файл main.c из репозитория с коммитом id=18411fd.

Мы видим, что теперь содержимое файла main.c соответствует тому, что было на момент создания коммита с id=18411fd. Сделаем коммит в репозиторий и в сообщении укажем, что он отменяет два предыдущих.

Таким образом мы вернулись к предыдущей версии файла main.c и при этом сохранили всю историю изменений.

Использование git revert для быстрой отмены изменений

Рассмотрим ещё одни способ отмены коммитов, на этот раз воспользуемся командой git revert.

В нашем примере, отменим коммит с id=cffc5ad. После того как вы введете команду git revert (см. ниже), система git выдаст сообщение в текстовом редакторе, если вы согласны с тем, что будет написано в открытом файле, то просто сохраните его и закройте. В результате изменения будут применены, и автоматически сформируется и отправится в репозиторий коммит.

Если вы хотите поменять редактор, то воспользуйтесь командой.

Обратите внимание, что в этом случае будут изменены настройки для текущего репозитория. Более подробно об изменении настроек смотрите в “Git для начинающих. Часть 3. Настройка Git”

Проверим, применялась ли настройка.

Посмотрим на список коммитов в репозитории.

Содержимое файла вернулось к тому, что было сделано в рамках коммита с >

Отмена группы коммитов

ВНИМАНИЕ! Используйте эту команду очень аккуратно!

Если вы не знакомы с концепцией указателя HEAD, то обязательно прочитайте статью “ Git для начинающих. Часть 7. Поговорим о HEAD и tree-ish“. HEAD указывает на коммит в репозитории, с которого будет вестись дальнейшая запись, т.е. на родителя следующего коммита. Существует три опции, которые можно использовать с командой git reset для изменения положения HEAD и управления состоянием stage и рабочей директории, сейчас мы все это подробно разберем.

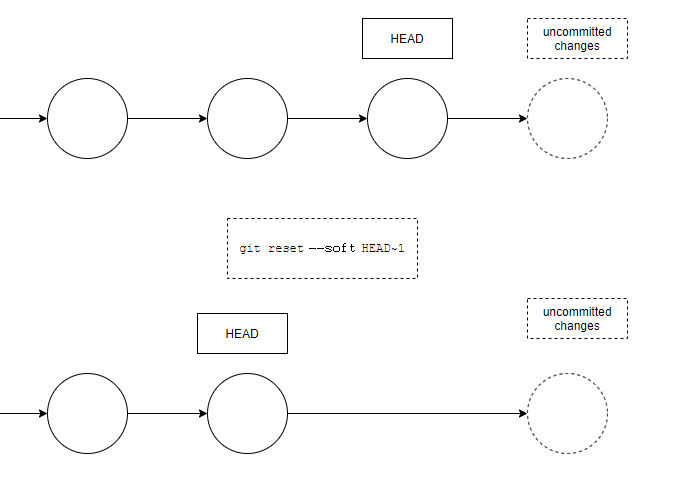

Удаление коммитов из репозитория (без изменения рабочей директории) (ключ –soft)

Для изменения положения указателя HEAD в репозитории, без оказания влияния рабочую директорию (в stage, при этом, будет зафиксированно отличие рабочей директории от репозитория), используйте ключ –soft. Посмотрим ещё раз на наш репозиторий.

Содержимое файла main.с в рабочей директории.

Содержимое файла main.с в репозитории.

Теперь переместим HEAD в репозитории на коммит с id=dcf7253.

Получим следующий список коммитов.

Содержимое файла main.c в репозитории выглядит так.

В рабочей директории файл main.c остался прежним (эти изменения отправлены в stage).

Для того, чтобы зафиксировать в репозитории последнее состояние файла main.c сделаем коммит.

Посмотрим на список коммитов.

Как видите из репозитория пропали следующие коммиты:

Удаление коммитов из репозитория и очистка stage (без изменения рабочей директории) (ключ –mixed)

Если использовать команду git reset с аргументом –mixed, то в репозитории указатель HEAD переместится на нужный коммит, а также будет сброшено содержимое stage. Отменим последний коммит.

В результате изменилось содержимое репозитория.

Содержимое файла main.c в последнем коммите выглядит так.

Файл main.c в рабочей директории не изменился.

Отправим изменения вначале в stage, а потом в репозиторий.

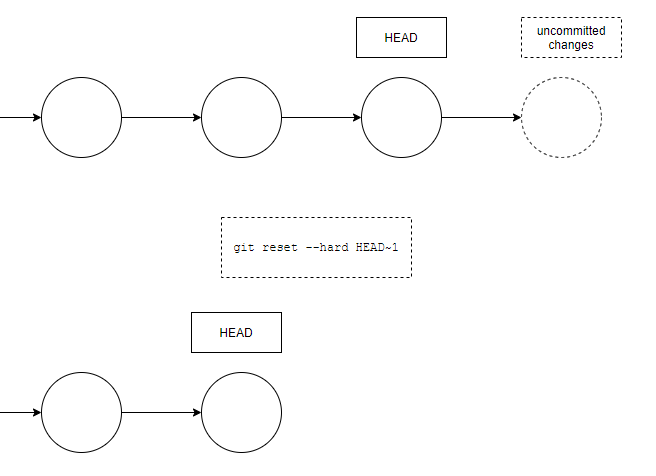

Удаление коммитов из репозитория, очистка stage и внесение изменений в рабочую директорию (ключ –hard)

Если вы воспользуетесь ключем –hard, то обратного пути уже не будет. Вы не сможете восстановить данные из рабочей директории. Все компоненты git (репозиторий, stage и рабочая директория) будут приведены к одному виду в соответствии с коммитом, на который будет перенесен указатель HEAD.

Текущее содержимое репозитория выглядит так.

Посмотрим на содержимое файла main.c в каталоге и репозитории.

Содержимое файлов идентично.

Удалим все коммиты до самого первого с id=86f1495.

Состояние рабочей директории и stage.

Содержимое файла main.c в репозитории и в рабочей директории.

Т.к. мы воспользовались командой git reset с ключем –hard, то восстановить прежнее состояние нам не получится.

БУДЬТЕ ОЧЕНЬ АККУРАТНЫ С ЭТОЙ КОМАНДОЙ!

Git для начинающих. Часть 9. Как удалить коммит в git? : 2 комментария

Это отменяет последний коммит, но не возвращает файл в исходное состояние.

А в какой задаче это может быть полезно?

Эта команда перезаписывает последний коммит (т.е. последний удаляется и на его место встает новый), файл в исходное состояние не возвращается.

А в какой задаче это может быть полезно?

хм… хороший вопрос! Даже затрудняюсь на него ответить. Ну например, вы закоммитили какой-то “ужас” и не хотите, чтобы он стал достоянием общественности))