How american spend their free time

How american spend their free time

5 graphs that reveal how Americans spend their free time

Money is a major factor.

By Eleanor Cummins | Updated Jul 28, 2021 3:07 PM

THE WORD LEISURE —time that belongs to you, free from work or other duties—dates to 14th-century Europe. But for much of its existence, the term was an abstract concept to all but the wealthy. That began to change in the United States in the late 1800s as laborers pushed for a 40-hour week. At long last, the masses could unwind at parks, theaters, and beaches.

Screen time

Kids get a bad rap for watching too much TV. But folks 65 and up are getting the most screen time: Older Americans take in more than four hours daily. It’s a great source of entertainment, yet it’s not universally good for you; excessive tube time encourages people to stay sedentary, which doesn’t do anyone’s heart, muscles, or bone density any favors.

Kidding aside

Children dictate how their caretakers spend their days. People with little ones under six, who require constant attention and active playtime, got just 18.6 minutes of relaxation a day in 2019. But it’s the parents of teens who get the least: They spend 11 minutes a day chilling out, and the rest of the time worrying what trouble their young adults are getting into.

Pushy notifications

The one thing money can’t buy is time. Too bad, because those with hefty salaries tend to have too little of it: just nine minutes of calm a day among top earners. Several social factors are at fault, but smartphones deserve the most blame. Those devices make it easy to play games or chat with friends at work, but they also let your boss ping you at all hours.

Workout break

If you want to get swole, consider getting rich first. High earners often have less downtime, but those in the top 25 percent spend an average of 21 minutes a day on sports and exercise—almost twice that of folks in the bottom 25 percent. But it’s not all good news. Although more money is correlated with more frequent trips to the gym, it’s also linked to more drinking.

Home life

Women typically enjoy less free time than men. It’s a sizable deficit too: 40.2 minutes daily in 2019. That’s because many work outside the home and also bear the most responsibility for child care and household chores. While they’re busy crossing things off their to-do lists, dudes are whiling away their extra time gaming or watching TV.

This story originally ran in the Spring 2021 Calm issue of PopSci. Read more PopSci+ stories.

The Free-Time Paradox in America

The rich were meant to have the most leisure time. The working poor were meant to have the least. The opposite is happening. Why?

«Every time I see it, that number blows my mind.”

Erik Hurst, an economist at the University of Chicago, was delivering a speech at the Booth School of Business this June about the rise in leisure among young men who didn’t go to college. He told students that one “staggering” statistic stood above the rest. «In 2015, 22 percent of lower-skilled men [those without a college degree] aged 21 to 30 had not worked at all during the prior twelve months,” he said.

«Think about that for a second,” he went on. Twentysomething male high-school grads used to be the most dependable working cohort in America. Today one in five are now essentially idle. The employment rate of this group has fallen 10 percentage points just this century, and it has triggered a cultural, economic, and social decline. «These younger, lower-skilled men are now less likely to work, less likely to marry, and more likely to live with parents or close relatives,” he said.

So, what are are these young, non-working men doing with their time? Three quarters of their additional leisure time is spent with video games, Hurst’s research has shown. And these young men are happy—or, at least, they self-report higher satisfaction than this age group used to, even when its employment rate was 10 percentage points higher.

It is a relief to know that one can be poor, young, and unemployed, and yet fairly content with life; indeed, one of the hallmarks of a decent society is that it can make even poverty bearable. But the long-term prospects of these men may be even bleaker than their present. As Hurst and others have emphasized, these young men have disconnected from both the labor market and the dating pool. They are on track to grow up without spouses, families, or a work history. They may grow up to be rudderless middle-aged men, hovering around the poverty line, trapped in the narcotic undertow of cheap entertainment while the labor market fails to present them with adequate working opportunities.

But when I tweeted Hurst’s speech this week, many people had a surprising and different take: That it was sad to think that a life of leisure should be so scary in the first place. After all, this was the future today’s workers were promised—a paradise of downtime for rich and poor, alike.

In the classic 1930 essay “Economic Possibility of Our Grandchildren,” the economist John Maynard Keynes forecast a future governed by a different set of expectations. The 21st century’s work week would last just 15 hours, he said, and the chief social challenge of the future would be the difficulty of managing leisure and abundance.

“For the first time since his creation man will be faced with his real, his permanent problem,” Keynes wrote, “how to use his freedom from pressing economic cares, how to occupy the leisure, which science and compound interest will have won for him, to live wisely and agreeably and well.»

The same idea was echoed in a 1957 book review for The New York Times, in which the writer Erik Barnouw predicted that, as work became easier and more machine-based, people would look to leisure to give their lives meaning.

The increasingly automatic nature of many jobs, coupled with the shortening work week, seem to be creating parallel tensions, which lead an increasing number of workers to look not to work but to leisure for satisfaction, meaning, expression … Today’s leisure occupations are no longer regarded merely as time fillers; the must, in the opinion of both social worker and psychiatrist, also perform to some extent as emotional buffers.

But 60 years later, it seems more true to say that it is not leisure that defines the lives of so many rich Americans. It is work.

Elite men in the U.S. are the world’s chief workaholics. They work longer hours than poorer men in the U.S. and rich men in other advanced countries. In the last generation, they have reduced their leisure time by more than any other demographic. As the economist Robert Frank wrote, “building wealth to them is a creative process, and the closest thing they have to fun.”

Here is the conundrum: Writers and economists from half a century ago and longer anticipated that the future would buy more leisure time for wealthy workers in America. Instead, it just bought them more work. Meanwhile, overall leisure has increased, but it’s the less-skilled poor who are soaking up all the free time, even though they would have the most to gain from working. Why?

Here are three theories.

1. The availability of attractive work for poor men (especially black men) is falling, as the availability of cheap entertainment is rising.

The most impressive technological developments since 1970 have been “channeled into a narrow sphere of human activity having to do with entertainment, communications, and the collection and processing of information,” the economist Robert Gordon wrote in his book The Rise and Fall of American Growth. As with any industry visited by the productivity gods, entertainment and its sub-kingdoms of music, TV, movies, games, and text (including news, books, and articles) have become cheap and plentiful.

Meanwhile, the labor force has erected several barriers for young non-college men, both overt—like the Great Recession and the decades-long demise of manufacturing jobs—and insidious. As the sociologist William Julius Wilson and the economist Larry Katz have both told me, the labor market’s fastest growing jobs are not historically masculine or particularly brawny. Rather they prize softer skills, as in retail, education, or patient-intensive health care, like nursing. In the 20th century, these jobs were filled by women, and they are still seen as feminine by many men who would simply rather not do them. Black men also face resistance among retail employers, who assume that potential customers will regard them as threatening.

And so, at the very moment that the labor market obliterated manufacturing jobs and shifted toward more soft-skill service jobs, diversion became a vastly discounted experience that could provide a moment’s joy at home. As a result, entertainment has become an inferior good, where the young and poor work less and play more.

2. Social forces cultivate a conspicuous industriousness (even workaholism) among affluent college graduates.

The first theory doesn’t do anything to explain why rich American men work so much harder than they used to, even though they are richer. That’s odd, since the point of earning money is ostensibly to afford things that make you happy, like free time.

But perhaps that’s just it: Rich, ambitious Americans are already spending more time on what makes them fulfilled, but that thing turned out to be work. Work, in this construction, is a compound noun, composed of the job itself, the psychic benefits of accumulating money, the pursuit of status, and the ability to afford the many expensive enrichments of an upper-class lifestyle.

In a widely shared essay in the Wall Street Journal last week, Hilary Potkewitz hailed 4 a.m. as «the most productive hour.» She quoted entrepreneurs, lawyers, career coaches, and cofounders praising the spiritual sanctity of the pre-dawn hours. As one psychiatrist told her, «when you have peace and quiet and you’re not concerned with people trying to get your attention, you’re dramatically more effective.»

Keynes envisioned a life with a little less work and a little more leisure, not a social competition to see who could maximize their pre-dawn productivity. But a 2016 essay about why Americans should sleep less to be more productive appeals specifically to a readership that considers downtime a worthy sacrifice upon the altar of productivity.

While some of the hardest-working rich Americans certainly love their jobs, it’s also likely that America’s secular religion of industriousness is a kind of pluralistic ignorance. That is, rich people work long hours because they are matching the behavior of similarly rich and ambitious people—e.g.: “he went to Bowdoin and Duke Law just like me, so if he stays in the office for 13 hours on Wednesday, I should too”—even though many participants in this pageant of workaholism would secretly prefer to work less and sleep at least until the sun is up.

3. Leisure is getting “leaky.”

Here is a third theory that applies equally to all income brackets: Thanks to smartphones and computers, leisure activity is leaking into work, and work, too, is leaking into leisure.

The radio set used to be a living room fixture. In order to listen to the radio, it was necessary to be at home. Then the car radio liberated the radio from the living room, and the television set replaced its corner of the living room. Then the smartphone liberated video from the television screen and put it on a mobile device that fit in people’s pockets.

Now somebody can listen to music, watch video, and read—while checking on social media feeds that can act as the cumulative equivalent of newspapers, magazines, and phone calls with friends—on their phone, while at work. Meanwhile, these same mobile instruments of leisure are also instruments of professional connectivity: When a boss knows that each of her workers have smartphones, she knows that they can all read her email on a Saturday morning (sent, naturally, at 4:01 a.m.).

My job fits snugly into this category. Writing is a leaky affair, where the boundaries between work and leisure are always porous. When I open Twitter, or watch the news on a Sunday morning, am I panning for golden nuggets of insight, taking a mental-health break, or something in between? It’s difficult to say; sometimes, I don’t even know. A novel that I read can become an article’s lede. A history book on my desk can inspire a column. Because the scope of non-fiction journalism is boundless, every moment of my downtime could theoretically surface an idea or stray comment that becomes a story. As a result, my weekdays feel more like weekends (and my weekends feel more like weekdays) than a 20th-century reporter’s.

Keynes got a lot wrong in 1930. He did not envision the rich working more, he did not foresee so many young men in poverty giving up on work, and he could not see the allure of cheap and personalized entertainment. But he accurately forecast the difficulty of a wealthy class transitioning to a more leisurely lifestyle. «The strenuous purposeful money-makers may carry all of us along with them into the lap of economic abundance,” Keynes wrote. “But it will be those peoples, who can keep alive, and cultivate into a fuller perfection, the art of life itself and do not sell themselves for the means of life, who will be able to enjoy the abundance when it comes.”

. How Americans Spend Their Leisure Time

The form and type of play and sports life which evolve in any group or nation mirror the development in other segments of the culture.

4. Some people are particularly concerned about the injuries that high school players get in football games. The pressure to “hit hard» and win high school games is intense.

5. In the past, teams and most players stayed in one city and bonded with the fans. Now professional sports are more about money and less about team loyalty.

6. The people who enjoy these physical activities often say that they find them very relaxing mentally because the activity is so different from the kind of activity they must do in the world of work, often indoor office work involving mind rather than body.

8. Computers are also extremely popular with children and teenagers, and this of course raises questions of where they are traveling on the Internet and what are they seeing. Now parents have to worry about monitoring the computer, in addition to monitoring the TV.

___________ 1. willing to work very hard at something

————— 2. parts or features of a whole system

____________ 3. develop by gradually changing

____________ 4. clear, direct

____________ 5. shown, faced with

____________ 6. very strong

————— 7. including something as a necessary part

____________ 8. affecting the mind

—————– 9. watching carefully

____________ 10. developed a special relationship

В. Classification: Recreational activities are usually not competitive and are done for fun, relaxation, and sometimes self-improvement. Sports are more organized and usually involve competition and rules of how to play.

do-it-yourself projects professional tennis going to the theater video games helicopter skiing*

A. Think about the quotation by the American Academy of Physical Education at the beginning of the chapter. Then discuss these questions with your classmates.

1. How do you think Americans like to spend their leisure time?

2. What are the advantages and disadvantages of playing competitive sports?

3. What do you know about Americans’ eating habits? What is “junk food»?

4. What is the impact of television on children?

5. How has technology impacted leisure time?

Most social scientists believe that the sports that are organized by a society

generally reflect the basic values of that society and attempt to strengthen them in the minds and emotions of its people. Therefore, organized sports may have a more serious social purpose than spontaneous, unorganized play by individuals. This is certainly true in the United States, where the three most popular organized sports are football, basketball, and baseball, with soccer gaining in popularity. Among young people, soccer is the game of choice. Boys and girls can play on the same team, and not much equipment is required. Nowhere are the ways and words of democracy better illustrated than in sports.

Organized sports are seen by Americans as an inspiring example of equality of opportunity in action. In sports, people of different races and economic backgrounds get an equal chance to excel. For this reason, notes sociologist Harry Edwards, Americans view organized sports as “a laboratory in which young men, regardless of social class, can learn the advantages and rewards of a competitive system.” Although Edwards specifically mentions young men, young women also compete in organized sports without regard to their race or economic background. The majority of American football and basketball players, both college and professional, are African- American, and about one-quarter of baseball players are Hispanics or Latinos. Women’s sports have grown in popularity in the United States, and they now have more funding and stronger support at the college level than in the past. The Olympics provide evidence of the increased interest in womens organized sports. American women have won gold medals for several team sports—softball, basketball, and soccer.

The American ideal of competition is

also at the very heart of organized sports in

the United States. Many Americans believe

that learning how to win in sports helps

develop the habits necessary to compete

successfully in later life. This training, in

turn, strengthens American society as a

whole. “It is commonly held,” says one

sports writer, “that the competitive ethic

taught in sports must be learned and

ingrained1 in youth for the future success of

American business and military efforts.”

The competitive ethic in organized

sports contains elements of hard work and

physical courage. Hard work is often called

“hustle,” “persistence,” or “never quitting” in

the sports world, while physical courage is

referred to as “being tough” or “having guts.” Mia Hamm, star of the American women’s soccer

team that has won two Olympic gold medals

1 ingrained: attitudes or behavior that are firmly established and therefore difficult to change

Hustle—you cant survive without it.

A quitter never wins; a winner never quits.

It’s easy to be ordinary, but it takes guts to excel.

6 A Ithough sports in the United States are glorified by many, there are others who./JLare especially critical of the power of sports to corrupt when certain things are carried to excess. An excessive desire to win in sports, for example, can weaken rather than strengthen traditional American values.

7 Critics have pointed out that there is a long tradition of coaches and players who have done just this. Vince Lombardi, a famous professional football coach, was often criticized for stating that winning is the “only thing” that matters in sports. Woody Hayes, another famous football coach, once said: “Anyone who tells me, ‘Don’t worry that you lost; you played a good game anyway,’ I just hate.” Critics believe that such statements by coaches weaken the idea that other things, such as fair play, following the rules, and behaving with dignity when one is defeated, are also important. Unfortunately, many coaches still share the “winning is the only thing” philosophy.

9 When the idea of winning in sports is carried to excess, however, honorable competition can turn into disorder and violence. In one game the players of two professional baseball teams became so angry at each other that the game turned into a large-scale fight between the two teams. The coach of one of the teams was happy about the fight because, in the games that followed, his team consistently won. He thought that the fight had helped to bring the men on his team closer together. Similarly, a professional football coach stated, “If we didn’t go out there and fight, I’d be worried. You go out there and protect your teammates. The guys who sit on the

bench, they’re the losers.” Both coaches seemed to share the view that if occasional fights with opposing teams helped to increase the winning spirit of their players, so much the better. Hockey coaches would probably agree. Professional hockey teams are notorious[100] for the fights among players during games. Some hockey fans seem to expect this fighting as part of the entertainment.

10

11 Most Americans would probably say that competition in organized sports does more to strengthen the national character than to corrupt it. They believe that eliminating competition in sports and in society as a whole would lead to laziness and vice rather than hard work and accomplishment. One high school principal, for example, described the criticism of competitive sports as “the revolutionaries’ attempt to break down the basic foundations upon which society is founded.” Comments of this sort illustrate how strong the idea of competition is in the United States and how important organized sports are as a means of maintaining this value in the larger society.

12 Another criticism of professional sports is that the players and the team owners get too much money, while fans have to pay more and more for tickets to the games. Basketball, baseball, and football stars get multi-million-dollar contracts similar to rock singers and movie stars. Some have asked whether these players are really athletes or entertainers. Furthermore, players are traded to other teams, or choose to go as “free agents,” and a whole team may move to another city because of money. In the past, teams and most players stayed in one city and bonded with the fans. Now professional sports are more about money and less about team loyalty. College football and basketball programs are also affected by big money. The teams of large universities generate millions of dollars, and there is enormous pressure on these sports programs to recruit top athletes and have winning seasons.

13 Another problem facing organized sports is the use of performance-enhancing drugs.[101] With the pressure to win so strong, a number of athletes have turned to these drugs. Although the use of most performance-enhancing drugs is illegal, it has now spread from professional sports down to universities and even high schools and middle schools. The use of these drugs puts the health of the athletes in danger and it is ethically wrong. It goes against the American values of equality of opportunity and fair competition. By 2004, the problem had become so significant that President George W. Bush mentioned it in his State of the Union address. He said, “Athletics play such an important role in our society, but, unfortunately, some in professional sports are not setting much of an example. The use of performance-enhancing drugs like steroids in baseball, football, and other sports is dangerous, and it sends the wrong message—that there are shortcuts to accomplishment, and that performance is more important than character.”

Some Americans prefer recreation that requires a high level of physical activity. This is true of the most popular adult recreational sports: jogging or running, tennis, and skiing. It would seem that some Americans carry over their belief in hard work into their world of play and recreation. The well-known expression “We like to work hard and play hard” is an example of this philosophy.

The high level of physical activity enjoyed by many Americans at play has led to the observation that Americans have difficulty relaxing, even in their leisure time. Yet the people who enjoy these physical activities often say that they find them very relaxing mentally because the activity is so different from the kind of activity they must do in the world of work, often indoor office work involving mind rather than body.

18 The interest that Americans have in self-improvement, traceable in large measure to the nations Protestant heritage (see Chapter 3), is also carried over into their recreation habits. It is evident in the joggers who are determined to improve the distance they can run, or the people who spend their vacation time learning a new sport such as sailing or scuba diving. The self-improvement motive, however, can also be seen in many other popular forms of recreation which involve little or no physical activity.

19 Interest and participation in cultural activities, which improve people’s minds or skills, are also popular. Millions of Americans go to symphony concerts, attend live theater performances, visit museums, hear lectures, and participate in artistic activities such as painting, performing music, or dancing. Many Americans also enjoy hobbies such as weaving, needlework, candle making, wood carving, quilting, and other handicrafts.[102] Community education programs offer a wide range of classes for those interested in anything from using computers to gourmet cooking, learning a foreign language, writing, art, self-defense, and bird-watching.

20

“It is as if they are looking for hardship,” one park official stated. “They seem to enjoy the danger and the physical challenge.”

Not all Americans want to “rough it” while they are on their adventure holidays, however. There are a number of travelers in their forties or fifties who want “soft adventure.” Judi Wineland, who operates Overseas Adventure Travel, says, “Frankly, it’s amazing to us to see baby boomers seeking creature comforts.” On her safari trips to Africa she has to provide hot showers, real beds, and night tables. The Americans’ love of comfort, mentioned in Chapter 5, seems to be competing with their desire to feel self-reliant and adventurous.

22 ot all Americans are physically fit, or even try to be. The overall population is

І. ЛІ becoming overweight, due to poor eating habits and a sedentary[103] lifestyle. Government studies estimate that less than half of Americans exercise in their leisure time. Experts say that it is not because Americans “don’t know what’s good for them”—they just don’t do it. By mid-2000, the Centers for Disease Control sounded the alarm—almost two-thirds of Americans were overweight, and more than one in five were obese. The CDC reported that obesity had become a national epidemic.

The sharp increase in childhood obesity has officials concerned that future generations will develop ailments such as Type 2 diabetes and heart disease at earlier ages than previous ones.

ф I960 О 1980 О 2000

Source: American Demographics, December 2003/January 2004, www. demographics. com.

After smoking, obesity was the number-two preventable cause of death in the United States. The government began a campaign to urge people to lose weight and get more exercise.

23 It’s not that Americans lack information on eating well. Newspapers and magazines are full of advice on nutrition, and diet books are best-sellers. Indeed, part of the problem may be that there is too much information in the media, and much of it is contradictory. For thirty years the government encouraged people to eat a diet high in

carbohydrates and low in fat, to avoid health risks such as heart disease and certain types of cancer. Many Americans ate low-fat, high-carbohydrate foods and gained weight. Then in the early 2000s, high-protein, low-carbohydrate diets became popular.

24 Many Americans have tried a number of diets, searching for the magic right one for them. Some overweight people say the diet advice is so confusing that they have just given up and eat whatever they want. Since 1994, the government has required uniform labeling so that consumers can compare the calories, fat, and carbohydrates in the food they buy. More than half of Americans say they pay attention to the nutritional content of the food they eat, but they also say they eat what they really want when they feel like it. For example, they have switched to skim milk but still buy fancy, fat-rich ice cream. As one American put it, “Lets face it—if you’re having chips and dip as a snack, fat-free potato chips and fat-free sour cream just don’t taste as good as the real thing.”

25 Experts say that it is a combination of social, cultural, and psychological factors that determine how people eat. A Newsweek article on America’s weight problems refers to “the culture of over – indulgence”7 seemingly ingrained in American life. “The land of plenty seems destined to include plenty of pounds as well,” they conclude. Part of the problem is that Americans eat larger portions8 and often go back for second helpings, in contrast to how much people eat in many other countries.

26 Another factor is Americans’ love of fast food. Although the fast – food industry is offering salads on its menus, most Americans still prefer “junk food.” They consume huge quantities of pizza, hamburgers, French fries, and soft drinks at restaurants, not only because they like them, but also because these foods are often the cheapest items on the menu. Another significant factor is Americans’ busy lifestyle. Since so many women are working, families are eating a lot of fast food, frozen dinners, and restaurant takeout. Some experts believe that Americans have really lost control of their eating; it is not possible to limit calories when they eat so much restaurant and packaged food. It takes time to prepare fresh vegetables and fish; stopping at a fast-food chain for fried chicken on the way home from work is a much faster alternative. Often, American families eat “on the run” instead of sitting down at the table together.

Amount hr torvlne

Calories! 10 Calories from Fat 50

27 T ronically, as Americans have gotten heavier as a population, the image of a

JL beautiful woman has gotten much slimmer. Marilyn Monroe, a movie star of the

1950s and 1960s, would be overweight by today’s media standards. Television shows,

movies, and TV commercials feature actresses who are very slender.9 Beer and soft

drink commercials, for example, often feature very thin girls in bikinis. As a result,

many teenage girls have become insecure about their bodies and so obsessed10 with

losing weight that some develop eating disorders such as anorexia or bulimia.

7 overindulgence: the habit of eating or drinking too much

8 portions: the amount of food for one person, especially when served in a restaurant

9 slender: thin, graceful, and attractive

10 obsessed: thinking about a person or a thing all the time and being unable to think of anything else

|

|

Another irony is that although television seems to promote images of slender, physically fit people, the more people watch TV, the less likely they are to exercise. Television has a strong effect on the activity level of many Americans. Some people spend much of their free time lying on the couch watching TV and eating junk food. They are called “couch potatoes,” because they are nothing but “eyes.” (The small marks on potatoes are called eyes.) Couch potatoes would rather watch a baseball game on TV than go play softball in the park with friends, or even go to a movie. Cable and satellite TV bring hundreds of stations into American homes, so there is an almost limitless choice of programs.

29 With so many programs to choose from, it is not surprising that the average family TV set is on about six hours a day. Estimates are that some children spend twenty hours or more a week watching TV programs and DVDs. Many adults are worried about the impact of so much television on the nation’s children. They are not getting as much exercise as they should, and the level of childhood obesity is alarming. But the effect on their minds may be as serious as the effect on their bodies. Many children do not spend enough time reading, educators say. And some studies have shown that excessive watching of television by millions of American children has lowered their ability to achieve in school.

30 One effect of watching so much TV seems to be a shortening of children’s attention span.11 Since the advent of the remote control device and the proliferation[104] [105] of channels, many watchers like to “graze” from one program to the next, or “channel surf”—constantly clicking the remote control to change from channel to channel, stopping for only a few seconds to see if something catches their attention.

34 Others argue that parents are responsible for supervising their children’s TV viewing. But how? Children are often watching television when their parents are not in the room, or even at home. Many parents think they can use help in monitoring what their children see. The reality is that one in four families is headed by a single parent, and in two-thirds of the two-parent families, both parents are working. Furthermore, about half of the children between the ages of six and seventeen have their own TV sets in their bedrooms. The possession of their own TV is an indication of both the material wealth and the individual freedom that many children have in the United States. We will explore these issues more in the next chapter.

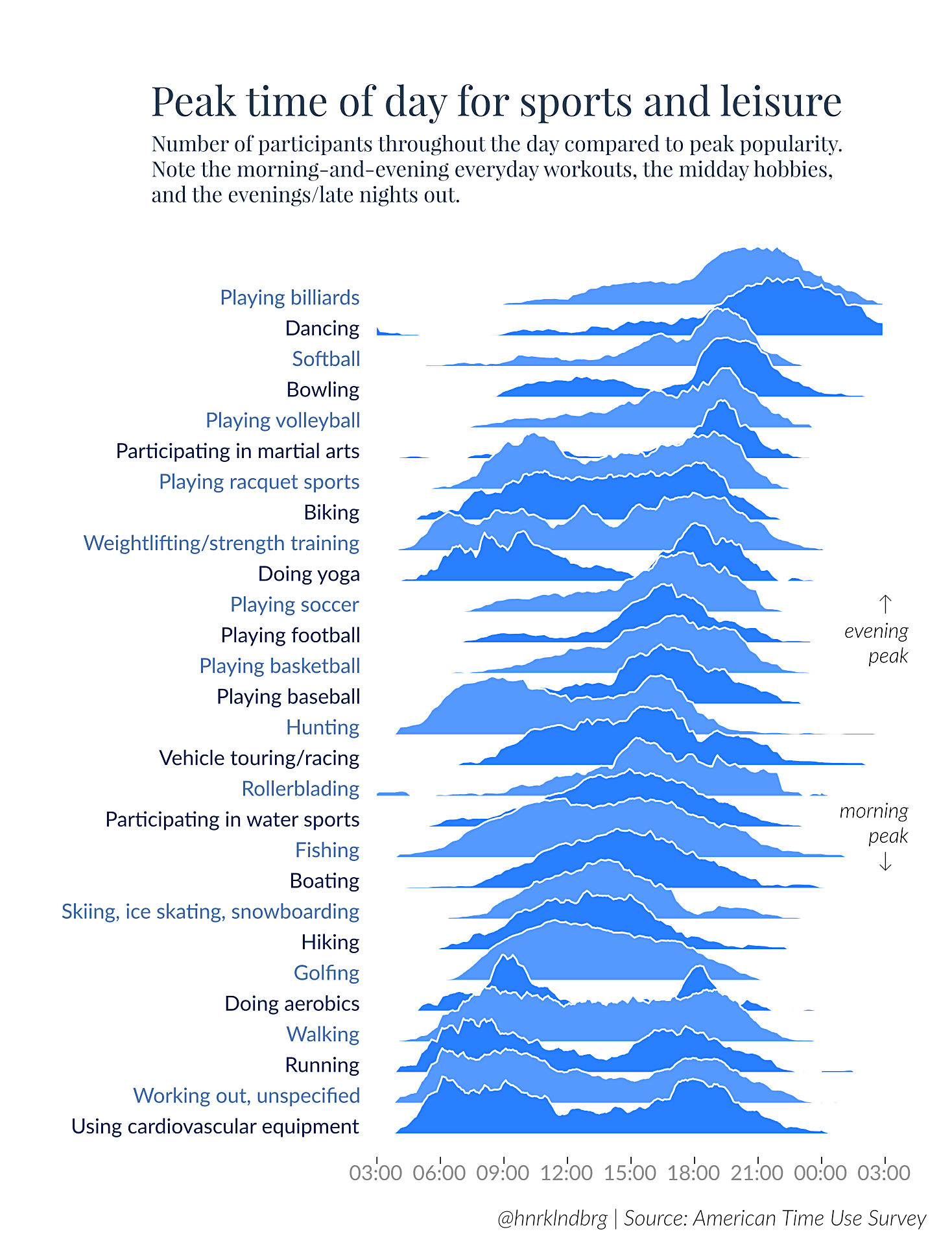

How Americans Spend Their Free Time, Part 2

Last week, we showed you how Americans spend their free time, as divided by different income groups. This week’s visualization is a continuation of that theme – it also comes from data scientist Henrik Lindberg, and it shows the peak times that Americans do certain leisure activities.

Again, data is coming from the American Time Use Survey that is produced by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS).

Peak Leisure Times

It’s clear that some activities have very distinct peaks for when participation rates reach their maximum share.

After work, for example, in the time period between 6:00pm and 9:00pm is when most Americans play softball, bowling, and volleyball in their free time. Later on, is when they would go dancing or play late-night billiards – often not coming back until the early morning hours.

Other team sports like football, baseball, and soccer also have distinct maximums. These ones are a little earlier in the afternoon or evening, before softball, bowling, and volleyball reach their peaks.

Keeping It Steady

Other activities have local peaks found throughout the day, or they simply have flatter distributions that represent steadier participation rates over time.

Fitness is particularly interesting to look at – for solo physical activities like running, working out, doing aerobics, or using cardiovascular equipment, there are two peaks: one in the morning, and one in the evening. The local peaks in the evening are usually not as high as their morning counterparts.

On the other hand, some activities are done at fairly equal rates throughout the day. When people go fishing, they are usually holding their rods pretty equally from 9am through to 6pm. Hunting is similar, though it starts far earlier in the day, and tails off faster than fishing as well. Two other activities that have pretty even distributions throughout the day are biking and racket sports like tennis, badminton, or squash.

The Least and Most Trusted News Sources in America

Here’s How Americans Spend Their Time, Sorted by Income

You may also like

The Richest Women in America in One Graphic

Visualizing the Highest-Paid Athletes in 2021

Olympic Medal Count: How Did Each Country Fare at Tokyo 2020

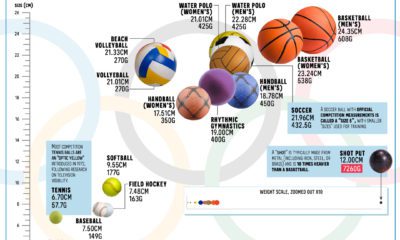

Olympics 2021: Comparing Every Sports Ball

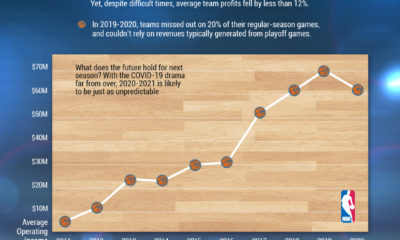

A Decade of NBA Profit: How Did the League Fare in 2020?

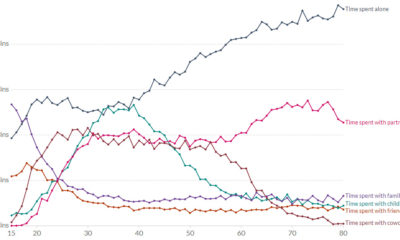

Who Americans Spend Their Time With, by Age

Technology

Every Mission to Mars in One Visualization

This graphic shows a timeline of every mission to Mars since 1960, highlighting which ones have been successful and which ones haven’t.

Timeline: A Historical Look at Every Mission to Mars

Within our Solar System, Mars is one of the most similar planets to Earth—both have rocky landscapes, solid outer crusts, and cores made of molten rock.

Because of its similarities to Earth and proximity, humanity has been fascinated by Mars for centuries. In fact, it’s one of the most explored objects in our Solar System.

But just how many missions to Mars have we embarked on, and which of these journeys have been successful? This graphic by Jonathan Letourneau shows a timeline of every mission to Mars since 1960 using NASA’s historical data.

A Timeline of Mars Explorations

According to a historical log from NASA, there have been 48 missions to Mars over the last 60 years. Here’s a breakdown of each mission, and whether or not they were successful:

The first mission to Mars was attempted by the Soviets in 1960, with the launch of Korabl 4, also known as Mars 1960A.

As the table above shows, the voyage was unsuccessful. The spacecraft made it 120 km into the air, but its third-stage pumps didn’t generate enough momentum for it to stay in Earth’s orbit.

For the next few years, several more unsuccessful Mars missions were attempted by the USSR and then NASA. Then, in 1964, history was made when NASA launched the Mariner 4 and completed the first-ever successful trip to Mars.

The Mariner 4 didn’t actually land on the planet, but the spacecraft flew by Mars and was able to capture photos, which gave us an up-close glimpse at the planet’s rocky surface.

Then on July 20, 1976, NASA made history again when its spacecraft called Viking 1 touched down on Mars’ surface, making it the first space agency to complete a successful Mars landing. Viking 1 captured panoramic images of the planet’s terrain, and also enabled scientists to monitor the planet’s weather.

Vacation to Mars, Anyone?

To date, all Mars landings have been done without crews, but NASA is planning to send humans to Mars by the late 2030s.

And it’s not just government agencies that are planning missions to Mars—a number of private companies are getting involved, too. Elon Musk’s aerospace company SpaceX has a long-term plan to build an entire city on Mars.

Two other aerospace startups, Impulse and Relativity, also announced an unmanned joint mission to Mars in July 2022, with hopes it could be ready as soon as 2024.

As more players are added to the mix, the pressure is on to be the first company or agency to truly make it to Mars. If (or when) we reach that point, what’s next is anyone’s guess.

How Americans Spend Their Time

DEFINING LEISURE AND RECREATION

The word «leisure» comes from the Latin word licere, which means «to be allowed.» A common American view considers leisure as something allowed after one’s work is done: time that is free after required activities. Recreation, however, is a different matter. The Oxford American Dictionary defines recreation as «a process or means of refreshing or entertaining oneself after work by some pleasurable activity.» Its Latin and French roots, which mean «restore to health» or «create anew,» suggest rejuvenation of strength or spirit. While leisure activities are pastimes, recreational activities are intended to restore physical or mental health.

HOW MUCH FREE TIME?

Americans enjoy some of the highest standards of living in the world. Although the United States trails other countries in such significant measures of health and wellbeing as infant mortality and life expectancy, the world generally respects—even envies—the quality of life enjoyed by most Americans.

Americans do work hard. Although the number of hours of nonwork time available to Americans has not changed significantly since the 1970s, public opinion surveys consistently report that Americans believe they have less free time today than in the past. Workers who participated in the Shell Poll, a study conducted by Shell Oil Company in 2000, indicated that if given a choice between an extra day off from work or an extra day’s wages every two weeks, they preferred more time off by a margin of 58% to 40%. For workers aged thirty-five to sixty-four, 67% indicated that they would rather have more time off.

Working parents report the least free time. According to the Shell Poll, only 48% of mothers believe they have enough personal leisure time. This reflects a dramatic decline from a Gallup survey conducted in 1963, when 70% of mothers were happy with their free time. Almost three-quarters of working mothers reported to Shell that on Sunday nights, after doing household chores and running errands on weekends, they do not feel rested and ready for a new work week.

In the free time Americans do have, they are sleeping less. According to Sleep in America, a survey published in 2002 by the nonprofit National Sleep Foundation, 68% of poll respondents admitted getting less than eight hours’ sleep on weeknights. Nearly a quarter of those surveyed believed they were not getting the minimum amount needed to avoid feelings of drowsiness during the day.

A PERSONAL CHOICE

People who perform certain activities all day at a job often pursue dramatically different activities during their time off. For example, someone who sits behind a desk at work may choose a physically active pastime, such as recreational walking. Similarly, a person with a job that requires demanding physical labor may choose a more sedentary activity, such as playing computer games, reading, or painting. A person who lives in a flat region may go to the mountains to seek excitement, while someone living in the mountains might seek a sandy ocean beach on which to relax.

Other people may enjoy one field so much that they perform that activity not only professionally but also as a form of recreation. For workers who derive little satisfaction from their occupation, recreation can become even more important to personal happiness.

HOW DO AMERICANS LIKE TO SPEND THEIR LEISURE TIME?

A survey conducted in October 2003 by Humphrey Taylor of the Harris organization asked Americans to name their two or three favorite ways to spend leisure time. The top response was reading, chosen by 24% of those polled, with watching television and spending time with family or children each following closely, both being cited by 17% of those asked. Other popular activities included fishing (9%), going to movies (7%), socializing with friends or neighbors (7%), playing team sports (6%), exercise activities such as weights and aerobics (6%), and gardening (6%). To a lesser extent the respondents also mentioned using a computer, participating in church activities, dining out, and watching sports (5% each); and walking, listening to music, shopping, traveling, hunting, and making crafts (4% each), among other choices.

Over the eight-year span this poll was conducted, the popularity of most of these activities remained relatively constant, although watching television and reading showed slight declines over that time, with perhaps the most significant change being the decline in activities that involved exercise, which fell from 38% in 1995 to 29% in 2003.

Although Americans named these as their favorite recreational activities, the way they actually spent their leisure time was not necessarily the same, according to a 2001 survey conducted by the Leisure Trends Group. While this poll found reading to be the most-cited activity, when asked how they had spent their leisure time the previous day, twice as many survey respondents reported watching television as reading. Americans may also not always have a choice of how to spend their free time. For example, housecleaning ranked eighth in the survey of how Americans spent leisure time but did not rank at all among the top ten favorite leisure-time activities.

Teenagers

The 2003 Gallup Youth Survey found that teens’ favorite ways to spend an evening included hanging out with friends or family (34%); watching television, movies, or sports (19%); playing video games (8%); or playing sports/exercising (7%). Only 3% each said they liked to read or talk on the phone, and using the Internet or a computer, sleeping, shopping, listening to music, and eating were each mentioned by just 1%.

There were significant differences in responses between boys and girls—only 26% of boys liked to hang out with friends or family, while this activity was preferred by 43% of girls. On the other hand, 15% of boys mentioned playing video games, while no girls cited this activity. Five percent of girls liked to read, while only 1% of boys did, and 5% of girls liked to talk on the phone, while less than 1% of boys did. More than twice as many boys (10%) as girls (4%) said they liked to play sports or exercise.

READING

Reading is one of the favorite leisure activities of Americans. A 2002 Gallup poll found that the overwhelming majority (83.5%) of Americans said they had read all or part of at least one book in the year preceding the survey. The average number of books read per year was sixteen among those who had read one book or more.

Choosing Books to Read

According to a 2002 Gallup poll, Americans had a wide range of reading interests. Thirty percent of those polled said they were «very likely» to choose biographies or books about history, with thriller or suspense novels appealing to 24% of those who were asked. Books about religion or theology followed close behind, at 24%, while self-improvement books (23%), mystery novels (21%), current fiction (20%) and books about current events (16%) were also popular. When asked what motivated them to read, 32% said they did so for entertainment, while 47% said they primarily read to learn.

Reading interests differed depending on age, although there was some overlap in the subjects that drew the most readers. In Do Reading Tastes Age? (2003), Gallup researchers Jennifer Robison and Steve Crabtree found that a higher percentage of those aged eighteen to twenty-nine said that they were «very likely» or «somewhat likely» to read horror novels (44%) than those age sixty-five and older (7%); the same relationship held up for science fiction novels, with 40% of young adults citing these compared to 23% of seniors. Americans between thirty and forty-nine had the most interest in business management and leadership books (48%) and personal finance books (44%) of any age group, perhaps due to their need to enhance careers or pay for the costs of raising children and sending them to college. Biographies and books about history (the most popular category overall), mystery novels, thriller or suspense novels, classic literature, current events books, books on religion and theology, and current literary fiction held relatively steady among age groups, with the last-named category most popular with adults aged fifty to sixty-four (59%) and least popular with young adults and seniors (44% each). (See Table 1.1.)

SOCIALIZING

Second in popularity as a leisure-time activity, according to the Harris poll conducted by Taylor in 2003, was the time-honored tradition of socializing with family or children. When the 17% who named this activity were added to the 7% who cited socializing with friends or neighbors, the total who chose socializing was 24%, the same amount as the number one choice of reading.

TELEVISION VIEWING

Americans also spend a considerable amount of their leisure time in front of the television, according to Harris Interactive. Where once all television viewers had only a handful of broadcast networks to choose from, by 2003

| Public opinion on book selection, by age, 2003 | ||||

| WHEN CHOOSING BOOKS TO READ, HOW LIKELY ARE YOU TO SELECT A BOOK FROM EACH OF THE FOLLOWING CATEGORIES? | ||||

| (Base: Those who read at least one book in past year) | ||||

| Percent saying «somewhat likely» or «very likely» | ||||

| Type of book | 18–29 | 30–49 | 50–64 | 65 + |

| source: Jennifer Robison and Steve Crabtree, «Book Selection by Age,» in Do Reading Tastes Age?» http://www.gallup.com/content/default.aspx?ci=7732&pg=1 (accessed September 10, 2004). Copyright © 2003 by The Gallup Organization. Reproducedby permission of The Gallup Organization. | ||||

| Biographies or books about history | 72% | 72% | 74% | 76% |

| Business management and leadership books | 38% | 48% | 39% | 23% |

| Classic literature | 46% | 50% | 45% | 43% |

| Current events books | 49% | 53% | 57% | 53% |

| Current literary fiction | 44% | 54% | 59% | 44% |

| Horror novels | 44% | 21% | 17% | 7% |

| Mystery novels | 48% | 56% | 58% | 53% |

| Personal finance books | 29% | 44% | 31% | 27% |

| Religion and theology | 47% | 60% | 52% | 58% |

| Self improvement books | 60% | 60% | 60% | 49% |

| Thriller or suspense novels | 58% | 54% | 53% | 48% |

| Science fiction novels | 40% | 36% | 29% | 23% |

| Romance novels | 36% | 24% | 22% | 27% |

there were 283 different cable and satellite channels available, according to Screen Digest. A 2003 study done by Nielsen Media Research found that 73.9 million American households with televisions subscribed to at least a basic package of cable channels, while another 19.4 million had satellite systems. Combined, the two made up close to 90% of all viewing households.

The types of programs Americans watch has evolved over time as well. Hour-long dramas and half-hour comedies once dominated the prime time schedules of the three major networks (NBC, CBS, and ABC), but the success of Survivor and other so-called reality shows has changed the landscape of television. Some observers suggest that, like any fad, such programs will fade into the background after their novelty value has worn thin, while others believe that they will remain a permanent part of the major networks’ programming.

Many television viewers enjoy watching rented digital videodisc (DVD) or videocassette copies of movies at home. A 2001 Gallup poll found that 83% of all respondents stated that they had watched a movie at home in the month preceding the poll. Among young adults aged eighteen to twenty-nine, this figure was 96%. Older adults tended to watch the fewest movies at home.

COMPUTERS IN DAILY HOME USE

Personal computing is an important leisure activity for many Americans. Accessing the Internet, using educational or entertainment software, playing music, and communicating with friends or family are all typical activities of home computer users.

Internet Use

Americans’ use of the Internet has grown dramatically since the mid-1990s. In 1995 the Pew Research Center for The People & The Press found that just 14% of American adults were «online users,» a number that had increased to 46% of adults by March 2000, or eighty-six million people. By mid-2004 the Pew Internet & American Life Project found that nearly 63% of American adults (128 million) had gone online.

Internet access in public schools has increased dramatically since the mid-1990s, giving school children more opportunity to go online. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, in Internet Access in U.S. Public Schools and Classrooms: 1994-2002 (2003), by 2001 99% of American public schools had gained access to the Internet, up from just 35% in 1994. The report further noted that 92% of public schools offered Internet connections in instructional rooms in 2002, up from 3% in 1994.

Americans without Internet access in their homes or at school could also go online at local public libraries. According to researchers John Carlo Bertot and Charles R. McClure in Public Libraries and the Internet 2002: Internet Connectivity and Networked Services (December 2002), by 2002 95% of all public libraries provided public access to the Internet, and 100% of urban public libraries did.

The Pew Internet & American Life Project (Pew/Internet) found that in 2004 the Internet audience was not only growing but also increasingly resembled the population as a whole. Whereas white males were once by far the most common users of the Internet, women, African-Americans, and Hispanics were using it more and more. A Pew/Internet tracking survey conducted in May and June 2004 found that almost 66% of American males and 61% of American females went online, along with 59% of English-speaking Hispanics and 43% of African-Americans. (See Table 1.2.)

Pew/Internet found significant differences among age groups in Internet use in 2004. While 78% of those eighteen to twenty-nine were online, and 74% of Americans aged thirty to forty-nine were using the Internet, the number dropped to 60% of those fifty to sixty-four and just 25% of those aged sixty-five and over. (See Table 1.2.)

In Counting on the Internet, a 2002 Pew/Internet report, researchers concluded that the popularity and reliability of the Internet as a source of information had raised Americans’ expectations about the scope and availability of information online. Three-quarters of Internet users reported positive experiences in finding information about health care, government agencies, news, and shopping. Many users cited the Internet as the first place they turned to for news and information.

According to Pew/Internet surveys conducted from 2001 to 2004, nearly all persons with Internet access were sending e-mail (93%), while 84% used online search engines to find information, 84% looked for maps or driving directions, and more than three-quarters of users researched products before they bought them or went online in pursuit of information about their hobbies. Other common uses included looking for weather forecasts (75%), seeking travel information (73%), getting news (72%), looking for health or medical information (66%), or simply surfing the Web for fun (67%). Many also found the Web useful for shopping and other transactions, with 65% of Internet users buying a product online, 55% making travel reservations, 34% doing online banking, and 23% participating in an online auction. (See Table 1.3.)

In June 2004 Pew/Internet researchers estimated that 53% of American adults with Internet access, or sixty-eight million, went online on an average day. Typical daily Internet activities included sending e-mail (45%), using a search engine to find information (30%), getting news (27%), looking for information on a hobby or interest (21%), checking the weather (20%), and performing job-related research (19%). Only 2% said they downloaded music files, or went to a Web site to meet other people, while just 1% of those surveyed said their typical daily Internet activities included gambling or visiting adult Web sites. Nearly one-quarter went online for recreation—that is, to surf the Web with no specific purpose in mind. (See Table 1.4.)

A survey conducted in November and December 2003 by Pew/Internet found that music downloads declined dramatically after the RIAA began suing specific individuals. While a survey conducted in March through May 2003 found that 29% of Internet users (thirty-five million) regularly downloaded music files, by year’s end this had declined to just 14% (eighteen million). In February and March 2004, however, Pew/Internet found that the percentage of downloaders had rebounded to 18% (twenty-three million). (See Table 1.5.) Many were now using such paid services as Apple’s iTunes, Musicmatch.com, or the relaunched, fee-charging Napster.

As Internet connection speeds and computer data storage capacity continued to increase, data-intensive video downloads were becoming popular as well, with 15% of Internet users reporting to Pew/Internet researchers in February and March of 2004 that they had downloaded videos from the Web. (See Table 1.5.) While some downloads, like movie trailers and commercials, were from legitimate Web sites, others were not. The Motion Picture Association of America issued a number of warnings in 2004 that copyright infringement lawsuits

| Internet activities, 2001–04 | ||

| Percent of those with Internet access | Most recentsurvey date | |

| source: «Internet Activities,» in Pew Internet & American Life Project Tracking Surveys (March 2000–Present), Pew Internet & American Life Project, http://www.pewinternet.org/trends/Internet_Activities_4.23.04.htm (accessed July 7, 2004) | ||

| Send e-mail | 93 | May-June 2004 |

| Use a search engine to find information | 84 | May-June 2004 |

| Search for a map or driving directions | 84 | Feb-04 |

| Do an Internet search to answer a specific question | 80 | Nov-Dec 2003 |

| Research a product or service before buying it | 78 | Feb-04 |

| Look for info on a hobby or interest | 76 | March-May 2003 |

| Check the weather | 75 | Jun-03 |

| Get travel info | 73 | May-June 2004 |

| Get news | 72 | May-June 2004 |

| Surf the Web for fun | 67 | March-May 2003 |

| Look for health/medical info | 66 | Dec-02 |

| Look for info from a government website | 66 | Aug-03 |

| Buy a product | 65 | Feb-04 |

| Research for school or training | 60 | May-June 2004 |

| Buy or make a reservation for travel | 55 | May-June 2004 |

| Go to a website that provides info or support for a specific medical condition or personal situation | 54 | Dec-02 |

| Look up phone number or address | 54 | Feb-04 |

| Watch a video clip or listen to an audio clip | 52 | March-May 2003 |

| Do any type of research for your job | 51 | Feb-04 |

| Look for political news/info | 49 | May-June 2004 |

| Get financial info | 44 | March-May 2003 |

| Check sports scores or info | 43 | Feb-04 |

| Look for info about a job | 42 | May-June 2004 |

| Download other files such as games, videos, or pictures | 42 | Jun-03 |

| Send an instant message | 42 | May-June 2004 |

| Play a game | 39 | March-May 2003 |

| Listen to music online at a website | 34 | May-June 2004 |

| Look for info about a place to live | 34 | May-June 2004 |

| Bank online | 34 | Jun-03 |

| Look for religious/spiritual info | 29 | March-May 2003 |

| Search for info about someone you know or might meet | 28 | Sep-02 |

| Chat in a chat room or in an online discussion | 25 | June-July 2002 |

| Research your family’s history or genealogy | 24 | March-May 2003 |

| Look for weight loss or general fitness info | 24 | Jan-02 |

| Participate in an online auction | 23 | Feb-04 |

| Look for info about a mental health issue | 23 | June-July 2002 |

| Share files from own computer w/ others | 23 | Feb-04 |

| Use Internet to get photos developed/display photos | 21 | August-October 2001 |

| Download music files to your computer | 20 | May-June 2004 |

| Create content for the Internet | 19 | Oct-02 |

| Look for info on something sensitive or embarrassing | 18 | June-July 2002 |

| Read someone else’s web log or «blog» | 17 | Feb-04 |

| Log onto the Internet using a wireless device | 17 | Feb-04 |

| Take part in an online group | 16 | Oct-02 |

| Download video files to your computer | 15 | Feb-04 |

| Visit an adult website | 15 | May-June 2004 |

| Buy or sell stocks, bonds, or mutual funds | 12 | Feb-04 |

| Buy groceries online | 12 | March-May 2003 |

| Take a class online for college credit | 10 | Jun-03 |

| Go to a dating website or other sites where you can meet other people online | 9 | May-June 2004 |

| Take any other class online | 8 | Jun-03 |

| Look for info about domestic violence | 8 | Dec-02 |

| Make a phone call online | 7 | Jun-03 |

| Make a donation to a charity online | 7 | Dec-02 |

| Create a web log or «blog» | 5 | Feb-04 |

| Check e-mail on a hand-held computer | 5 | August-October 2001 |

| Play lottery or gamble online | 4 | March-May 2003 |

would be brought against those sharing movies via peer-to-peer networks.

Teens and College Students on the Internet

The Pew Internet & American Life Project estimated in 2003 that 78% of Americans aged twelve to seventeen were online. Of these, 92% used e-mail, 84% surfed the Web for fun, 74% used instant messaging, and 71% had used the Internet as the major source for their most recent major school project.

According to the 2002 Pew/Internet report The Internet Goes to College, college students were among the heaviest users of the Internet. This finding was not surprising since about one-fifth of the surveyed college students had begun using computers as young children. All

| Daily Internet activities, 2001–04 | ||

| Percent of those with Internet access | Most recent survey date | |

| *Percentage of Internet users who do these activities on a typical day is less than 1% | ||

| source: «Daily Internet Activities,» in Pew Internet & American Life Project Tracking Surveys (March 2000–Present), Pew Internet & American Life Project, http://www.pewinternet.org/trends/Daily_Activities_4.23.04.htm (accessed July 7, 2004) | ||

| Go online | 53 | May-June 2004 |

| Send e-mail | 45 | May-June 2004 |

| Use a search engine to find information | 30 | May-June 2004 |

| Get news | 27 | May-June 2004 |

| Surf the Web for fun | 23 | March-May 2003 |

| Look for info on a hobby or interest | 21 | March-May 2003 |

| Do an Internet search to answer a specific question | 21 | Nov-Dec 2003 |

| Check the weather | 20 | Jun-03 |

| Do an Internet search to answer a specific question | 19 | Sep-02 |

| Do any type of research for your job | 19 | February 2004 |

| Research a product or service before buying it | 15 | Feb-04 |

| Look for political news/info | 13 | May-June 2004 |

| Send an instant message | 12 | May-June 2004 |

| Get financial info | 12 | March-May 2003 |

| Check sports scores and info | 11 | Feb-04 |

| Watch a video clip or listen to an audio clip | 11 | March-May 2003 |

| Research for school or training | 11 | May-June 2004 |

| Look for info from a government website | 9 | Jun-03 |

| Play a game | 9 | March-May 2003 |

| Bank online | 9 | Jun-03 |

| Get travel info | 8 | May-June 2004 |

| Look up phone number or address | 7 | Feb-04 |

| Search for a map or driving directions | 7 | Feb-04 |

| Log onto the Internet using a wireless device | 6 | Feb-04 |

| Look for health/medical info | 6 | Dec-02 |

| Take part in an online group | 6 | Oct-02 |

| Listen to music online at a website | 6 | May-June 2004 |

| Download other files such as games, videos, or pictures | 6 | Jun-03 |

| Create content for the Internet | 4 | Oct-02 |

| Look for religious/spiritual info | 4 | March-May 2003 |

| Chat in a chat room or in an online discussion | 4 | June-July 2002 |

| Look for info about a job | 4 | May-June 2004 |

| Go to a website that provides info or support for a specific medical condition or personal situation | 4 | Dec-02 |

| Look for info about a place to live | 3 | May-June 2004 |

| Buy or make a reservation for travel | 3 | May-June 2004 |

| Participate in an online auction | 3 | Feb-04 |

| Read someone else’s web log or «blog» | 3 | Feb-04 |

| Buy a product | 3 | Feb-04 |

| Search for info about someone you know or might meet | 3 | Sep-02 |

| Look for weight loss or general fitness info | 3 | Jan-02 |

| Share files from own computer w/ others | 2 | February 2004 |

| Download video files to your computer | 2 | Feb-04 |

| Download music files to your computer | 2 | May-June 2004 |

| Go to a dating website or other sites where you can meet other people online | 2 | May-June 2004 |

| Visit an adult website | 1 | May-June 2004 |

| Buy groceries online | 1 | March-May 2003 |

| Create a web log or «blog» | 1 | Feb-04 |

| Buy or sell stocks, bonds, or mutual funds | 1 | Feb-04 |

| Look for info about a mental health issue | 1 | June-July 2002 |

| Play lottery or gamble online | 1 | March-May 2003 |

| Use Internet to get photos developed/display photos | 1 | August-October 2001 |

| Check e-mail on a hand-held computer | 1 | August-October 2001 |

| Research your family’s history or genealogy | 1 | March-May 2003 |

| Take a class online for college credit | * | Jun-03 |

| Take any other class online | * | Jun-03 |

| Make a phone call online | * | Jun-03 |

| Make a donation to a charity online | * | Dec-02 |

| Look for info about domestic violence | * | Dec-02 |

| Look for info on something sensitive or embarrassing | * | June-July 2002 |

college students who responded to the survey had used computers by age 16, and most were Internet users.

A study published in 2004 in the Journal of College and University Student Housing found that of 253 freshmen and sophomores living in residence halls at Ball State University, 94% had access to a computer in their living quarters, and 75% reported using computer technology more than five hours per week. Seventy percent of the students reported using a computer daily or several times per week to complete assignments or papers, and 59% reported

| Internet music and video downloads, 2004 | ||||

| (In percent) | ||||

| I’M GOING TO READ YOU [A] SHORT LIST OF ACTIVITIES. PLEASE TELL ME IF YOUEVER DO ANY OF THE FOLLOWING WHEN YOU GO ONLINE. DO YOU EVER…/DID YOU HAPPEN TO DO THIS YESTERDAY, OR NOT? | ||||

| Total have ever done this | Did yesterday | Have not done this | Don’t know/refused | |

| source: Peter Rainie, Mary Madden, Dan Hess, and Graham Mudd, «February 2004 Pew Internet Tracking Survey Excerpt,» in Pew Internet Project and Comscore Media Metrix Data Memo, Pew Internet & American Life Project, April 2004, http://www.pewinternet.org/pdfs/PIP_Filesharing_April_04.pdf (accessed July 22, 2004) | ||||

| Download music files onto your computer so you can play them at any time you want | ||||

| Feb/March 2004 | 18 | 1 | 82 | * |

| Nov 2003 | 14 | 1 | 85 | * |

| June 2003 | 30 | 3 | 70 | * |

| April/May 2003 | 30 | 4 | 70 | * |

| March 12–192003 | 28 | 5 | 72 | * |

| Oct 2002 | 32 | 5 | 68 | * |

| Sept 12–192001 | 26 | 3 | 73 | * |

| Aug 2001 | 26 | 3 | 73 | * |

| Feb 2001 | 29 | 6 | 71 | * |

| Fall 2000 | 24 | 4 | 76 | * |

| July/August 2000 | 22 | 3 | 78 | * |

| Share files from own computer, such as music, video or picture files, or computer games with others online | ||||

| Feb/March 2004 | 23 | 2 | 77 | * |

| Nov 2003 | 20 | 4 | 79 | * |

| June 2003 | 28 | 5 | 72 | * |

| Sept 12–19,2001 | 28 | 4 | 72 | 1 |

| August 2001 | 25 | 4 | 75 | * |

| Download video files onto your computer so you can play them at any time you want | ||||

| Feb/March 2004 | 15 | 2 | 85 | * |

| Nov 2003 | 13 | 2 | 86 | * |

using one to surf the Internet. E-mail or instant messaging was used daily by 78%, with another 17% using such communications programs several times per week.

Computer Use among Older Adults

According to Pew/Internet, persons over age sixty-five were dispelling myths about their reluctance to embrace new technology, as they surfed the Web in record numbers. In 2000 an estimated 12% of older Americans were online, but this number had grown to 20% by 2002 and to 25% in the spring of 2004.

Computers have been readily integrated into the lives of older adults in many settings, ranging from nursing homes to senior recreation centers. For older adults who are homebound as a result of illness or disability, Internet access can offer opportunities to socialize, contact friends and family, and purchase food, medications, and other necessities without leaving their homes.

SPORTS AND FITNESS ACTIVITIES ARE IMPORTANT TO MANY AMERICANS

Like tastes in food, fashion, and music, American exercise habits have undergone significant shifts. Participation in sports and other fitness activities is important to many Americans. In Sports Participation Topline Report (2004), the Sporting Goods Manufacturers Association (SGMA) described facts about Americans who were frequent or occasional sports participants, along with Americans’preoccupation with fitness and trends in fitness activity (see Table 1.6):

The SGMA report also concluded that Americans preferred noncompetitive sports and fitness activities that were less intense. Of the top twenty most popular sports, basketball was the only team sport named. It claimed 35.4 million participants, twice as many as football’s eighteen million, soccer’s 17.7 million, and softball’s sixteen million.

America’s Most Popular Sports

The SGMA’s list of the top thirty most popular sports in America based on the number of participants for 2003 was topped by bowling, with fifty-five million. It was followed by treadmill exercise (45.6 million), freshwater fishing (43.8 million), stretching (42.1 million), tent camping (41.9 million), and billiards (40.7 million). Twelve of the top thirty were fitness-related activities. (See Table 1.7.)

Gender and Age Influence Sports and Fitness Choices

Athletically inclined American men seemed to prefer individual rather than team sports. Fourteen out of the top fifteen most popular sports for male participants were solo activities. The most popular sports activity for men in 2003 was freshwater fishing, with 9.2 million participating in it at least fifteen days during the year. Men also found fitness activities appealing, with 8.5 million of them lifting barbells a hundred or more days a year, and 7.9 million lifting dumbbells. Stretching (7.6 million),

| Sports participation trends, reported by SGMA International, selected years 1987–2003 | ||||||||

| 1987 Benchmark | 1993 | 1998 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 1 year% change (2002–2003) | 16 year% change (1987–2003) | |

| Fitness activities | ||||||||

| Aerobics (high impact) | 13,961 | 10,356 | 7,460 | 6,401 | 5,423 | 5,875 | +8.3 | −57.9 |

| Aerobics (low impact) | 11,888 | 13,418 | 12,774 | 10,026 | 9,286 | 8,813 | −5.1 | −25.9 |

| Aerobics (step) | n.a. | 11,502 | 10,784 | 8,542 | 8,336 | 8,457 | +1.5 | −26.5 2 |

| Aerobics (net) | 21,225 | 24,839 | 21,017 | 16,948 | 16,046 | 16,451 | +2.5 | −22.5 |

| Other exercise to music | n.a. | n.a. | 13,846 | 13,076 | 13,540 | 14,159 | +4.6 | +2.3 4 |

| Aquatic exercise | n.a. | n.a. | 6,685 | 7,103 | 6,995 | 7,141 | +2.1 | +6.8 4 |

| Calisthenics | n.a. | n.a. | 30,982 | 29,392 | 26,862 | 28,007 | +4.3 | −9.6 4 |

| Cardio kickboxing | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 6,665 | 5,940 | 5,489 | −7.6 | −27.8 5 |

| Fitness bicycling | n.a. | n.a. | 13,556 | 10,761 | 11,153 | 12,048 | +8.0 | −11.1 4 |

| Fitness walking | 27,164 | 36,325 | 36,395 | 36,445 | 37,981 | 37,945 | −0.1 | +39.7 |

| Running/Jogging | 37,136 | 34,057 | 34,962 | 34,857 | 35,866 | 36,152 | +0.8 | −2.6 |

| Fitness swimming | 16,912 | 17,485 | 15,258 | 15,300 | 14,542 | 15,899 | +9.3 | −6.0 |

| Pilates training | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 2,437 | 4,671 | 9,469 | +102.7 | +444.5 6 |

| Stretching | n.a. | n.a. | 35,114 | 38,120 | 38,367 | 42,096 | +9.7 | +19.9 4 |

| Yoga/Tai Chi | n.a. | n.a. | 5,708 | 9,741 | 11,106 | 13,371 | +20.4 | +134.3 4 |

| Equipment exercise | ||||||||

| Barbells | n.a. | n.a. | 21,263 | 23,030 | 24,812 | 25,645 | +3.4 | +20.6 4 |

| Dumbells | n.a. | n.a. | 23,414 | 26,773 | 28,933 | 30,549 | +5.6 | +30.5 4 |

| Hand weights | n.a. | n.a. | 23,325 | 27,086 | 28,453 | 29,720 | +4.5 | +27.4 4 |

| Free weights (net) | 22,553 | 28,564 | 41,266 | 45,407 | 48,261 | 51,567 | +6.9 | +128.6 |

| Weight/resistance machines | 15,261 | 19,446 | 22,519 | 25,942 | 27,848 | 29,996 | +7.7 | +96.6 |

| Home gym exercise | 3,905 | 6,258 | 7,577 | 8,497 | 8,924 | 9,260 | +3.8 | +137.1 |

| Abdominal machine/device | n.a. | n.a. | 16,534 | 18,692 | 17,370 | 17,364 | 0 | +5.0 4 |

| Rowing machine exercise | 14,481 | 11,263 | 7,485 | 7,089 | 7,092 | 6,484 | −8.6 | −55.2 |

| Stationary cycling (upright bike) | n.a. | n.a. | 20,744 | 17,483 | 17,403 | 17,488 | +0.5 | −15.7 4 |

| Stationary cycling (spinning) | n.a. | n.a. | 6,776 | 6,418 | 6,135 | 6,462 | +5.3 | −4.6 4 |

| Stationary cycling (recumbent bike) | n.a. | n.a. | 6,773 | 8,654 | 10,217 | 10,683 | +4.6 | +57.7 4 |

| Stationary cycling (net) | 30,765 | 35,975 | 30,791 | 28,720 | 29,083 | 30,952 | +6.4 | +0.6 |

| Treadmill exercise | 4,396 | 19,685 | 37,073 | 41,638 | 43,431 | 45,572 | +4.9 | +936.7 |

| Stair-climbing machine exercise | 2,121 | 22,494 | 18,609 | 15,117 | 14,251 | 14,321 | +0.5 | +575.2 |

| Aerobic rider | n.a. | n.a. | 5,868 | 3,918 | 3,654 | 2,955 | −19.1 | −49.6 4 |

| Elliptical motion trainer | n.a. | n.a. | 3,863 | 8,255 | 10,695 | 13,415 | +25.4 | +247.3 4 |

| Cross-country ski machine exercise | n.a. | 9,792 | 6,870 | 4,924 | 5,074 | 4,744 | −6.5 | −25.8 1 |

| Team sports | ||||||||

| Baseball | 15,098 | 15,586 | 12,318 | 11,405 | 10,402 | 10,885 | +4.6 | −27.1 |

| Basketball | 35,737 | 42,138 | 42,417 | 38,663 | 36,584 | 35,439 | −3.1 | −0.8 |

| Cheerleading | n.a. | 3,257 | 3,266 | 3,844 | 3,596 | 3,574 | −0.6 | +17.6 |

| Ice hockey | 2,393 | 3,204 | 2,915 | 2,344 | 2,612 | 2,789 | +6.8 | +16.5 |

| Field hockey | n.a. | n.a. | 1,375 | 1,249 | 1,096 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Football (touch) | 20,292 | 21,241 | 17,382 | 16,675 | 14,903 | 14,119 | −5.3 | −30.4 |

| Football (tackle) | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 5,400 | 5,783 | 5,751 | −0.6 | +16.6 5 |

| Football (net) | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 19,199 | 18,703 | 17,958 | −4.0 | −4.1 5 |

| Lacrosse | n.a. | n.a. | 926 | 1,099 | 921 | 1,132 | +22.9 | +22.2 4 |

| Rugby | n.a. | n.a. | 546 | 573 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Soccer (indoor) | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 4,563 | n.a. | n.a. |

| Soccer (outdoor) | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 16,133 | n.a. | n.a. |

| Soccer (net) | 15,388 | 16,365 | 18,176 | 19,042 | 17,641 | 17,679 | +0.2 | +14.9 |

| Softball (regular) | n.a. | n.a. | 19,407 | 17,679 | 14,372 | 14,410 | +0.3 | −25.7 4 |

| Softball (fast-pitch) | n.a. | n.a. | 3,702 | 4,117 | 3,658 | 3,487 | −4.7 | −5.8 4 |

| Softball (net) | n.a. | n.a. | 21,352 | 20,123 | 16,587 | 16,020 | −3.4 | −25.0 4 |

| Volleyball (hard surface) | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 12,802 | 11,748 | 11,008 | −6.3 | −14.0 7 |

| Volleyball (grass) | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 10,330 | 8,621 | 7,953 | −7.7 | −23.0 7 |

| Volleyball (beach) | n.a. | 13,509 | 10,572 | 7,791 | 7,516 | 7,454 | −0.8 | −35.5 1 |

| Volleyball (net) | 35,984 | 37,757 | 26,637 | 24,123 | 21,488 | 20,286 | −5.6 | −43.6 |

| Racquet sports | ||||||||

| Badminton | 14,793 | 11,908 | 9,936 | 7,684 | 6,765 | 5,937 | −12.2 | −59.9 |

| Racquetball | 10,395 | 7,412 | 5,853 | 5,296 | 4,840 | 4,875 | +0.7 | −53.1 |

| Squash | n.a. | n.a. | 289 | n.a. | 302 | 473 | +56.6 | n.a. |

| Tennis | 21,147 | 19,346 | 16,937 | 15,098 | 16,353 | 17,325 | +5.9 | −18.1 |

| Personal contact sports | ||||||||

| Boxing | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 932 | 908 | 945 | +4.1 | +4.5 5 |

| Martial arts | n.a. | n.a. | 5,368 | 5,999 | 5,996 | 6,883 | +14.8 | +28.2 4 |

| Wrestling | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 2,360 | 2,026 | 1,820 | −10.2 | −28.5 5 |

calisthenics (6.7 million), and fitness walking (6.6 million) followed closely behind. The highest-ranked team sport, basketball, was played by 5.6 million men at least once a week. (See Table 1.8.)

Women also chose individual fitness activities over team sports. In 2003 the most popular choices of female fitness enthusiasts included stretching (10.7 million participants), fitness walking (9.8 million), treadmill exercise

| Indoor sports | ||||||||

| Billiards/Pool | 35,297 | 40,254 | 39,654 | 39,263 | 39,527 | 40,726 | +3.0 | +15.4 |

| Bowling | 47,823 | 49,022 | 50,593 | 55,452 | 53,160 | 55,035 | +3.5 | +15.1 |

| Darts | n.a. | n.a. | 21,792 | 19,460 | 19,703 | 19,486 | −1.1 | −10.6 4 |

| Table tennis | n.a. | 17,689 | 14,999 | 13,239 | 12,796 | 13,511 | +5.6 | −32.7 1 |

| Wheel sports | ||||||||

| Roller hockey | n.a. | 2,323 | 3,876 | 2,733 | 2,875 | 2,718 | −5.5 | +17.0 2 |

| Roller skating (2×2 wheels) | n.a. | 24,223 | 14,752 | 11,443 | 10,968 | 11,746 | +7.1 | −56.7 1 |

| Roller skating (inline wheels) | n.a. | 13,689 | 32,010 | 26,022 | 21,572 | 19,233 | −10.8 | +309.6 1 |

| Scooter riding (non-motorized) | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 15,796 | 13,858 | 11,493 | −17.1 | −17.2 6 |

| Skateboarding | 10,888 | 5,388 | 7,190 | 12,459 | 12,997 | 11,090 | −14.7 | +1.9 |

| Other sports/activities | ||||||||

| Bicycling (BMX) | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 3,668 | 3,885 | 3,365 | −13.4 | −9.8 5 |

| Bicycling (recreational) | n.a. | n.a. | 54,575 | 52,948 | 53,524 | 53,710 | +0.3 | −1.6 4 |

| Golf | 26,261 | 28,610 | 29,961 | 29,382 | 27,812 | 27,314 | −1.8 | +4.0 4 |

| Gymnastics | n.a. | n.a. | 6,224 | 5,557 | 5,149 | 5,189 | +0.8 | −16.6 4 |

| Swimming (recreational) | n.a. | n.a. | 94,371 | 93,571 | 92,667 | 96,429 | +4.1 | +2.2 4 |

| Walking (recreational) | n.a. | n.a. | 80,864 | 84,182 | 84,986 | 88,799 | +4.5 | −9.8 4 |

| Outdoors activities | ||||||||

| Camping (tent) | 35,232 | 34,772 | 42,677 | 43,472 | 40,316 | 41,891 | +3.9 | +18.9 |

| Camping (recreational vehicle) | 22,655 | 22,187 | 18,188 | 19,117 | 18,747 | 19,022 | +1.5 | −16.0 |

| Camping (net) | 50,386 | 49,858 | 50,650 | 52,929 | 49,808 | 51,007 | +2.4 | +1.2 |

| Hiking (day) | n.a. | n.a. | 38,629 | 36,915 | 36,778 | 39,096 | +6.3 | +1.2 4 |

| Hiking (overnight) | n.a. | n.a. | 6,821 | 6,007 | 5,839 | 6,213 | +6.4 | −8.9 4 |

| Hiking (net) | n.a. | n.a. | 40,117 | 37,999 | 37,888 | 40,409 | +6.7 | +0.7 4 |

| Horseback riding | n.a. | n.a. | 16,522 | 16,648 | 14,641 | 16,009 | +9.3 | −3.1 4 |

| Mountain biking | 1,512 | 7,408 | 8,611 | 6,189 | 6,719 | 6,940 | +3.3 | +359.0 |

| Mountain/Rock climbing | n.a. | n.a. | 2,004 | 1,819 | 2,089 | 2,169 | +3.8 | +8.2 4 |

| Artificial wall climbing | n.a. | n.a. | 4,696 | 7,377 | 7,185 | 8,634 | +20.2 | +83.9 4 |

| Trail running | n.a. | n.a. | 5,249 | 5,773 | 5,625 | 6,109 | +8.6 | +16.4 4 |

| Shooting sports | ||||||||

| Archery | 8,558 | 8,648 | 7,109 | 6,442 | 6,650 | 7,111 | +6.9 | −16.9 |

| Hunting (shotgun/rifle) | 25,241 | 23,189 | 16,684 | 16,672 | 16,471 | 15,232 | −7.5 | −39.7 |

| Hunting (bow) | n.a. | n.a. | 4,719 | 4,435 | 4,752 | 4,155 | −12.6 | +12.0 4 |