How chocolate is produced

How chocolate is produced

The production of chocolate

Introduction

C hocolate is a key ingredient in many foods such as milk shakes, candy bars, cookies and cereals. It is ranked as one of the most favourite flavours in North America and Europe (Swift, 1998). Despite its popularity, most people do not know the unique origins of this popular treat. Chocolate is a product that requires complex procedures to produce. The process involves harvesting coca, refining coca to cocoa beans, and shipping the cocoa beans to the manufacturing factory for cleaning, coaching and grinding. These cocoa beans will then be imported or exported to other countries and be transformed into different type of chocolate products (Allen, 1994).

Click on the name to have a full map of the countres.

Top seven cocoa producing countries

ICCO forecasts of production of cocoa beans for the 1997/98 cocoa year

| Country | Production forecast for 1997/98: (in thousand tonnes) |

| Côte d’Ivoire | 1150.0 |

| Ghana | 370.0 |

| Indonesia | 310.0 |

| Brazil | 160.0 |

| Nigeria | 155.0 |

| Cameroon | 125.0 |

| Malaysia | 100.0 |

Reference:

Quarterly Bulletin of Cocoa Statistics, 24 (1), 1997/98

Source: International Cocoa organization, April 1998

Harvesting Cocoa & Cocoa processing

Step #1: Plucking and opening the Pods

Cocoa beans grow in pods that sprout off of the trunk and branches of cocoa trees. The pods are about the size of a football. The pods start out green and turn orange when they’re ripe. When the pods are ripe, harvesters travel through the cocoa orchards with machetes and hack the pods gently off of the trees.

Cocoa Pods and harvesting

Machines could damage the tree or the clusters of flowers and pods that grow from the trunk, so workers must be harvest the pods by hand, using short, hooked blades mounted on long poles to reach the highest fruit.

Step #2: Fermenting the cocoa seeds

Now the beans undergo the fermentation processing. They are either placed in large, shallow, heated trays or covered with large banana leaves. If the climate is right, they may be simply heated by the sun. Workers come along periodically and stir them up so that all of the beans come out equally fermented. During fermentation is when the beans turn brown. This process may take five or eight days.

The fermentation of Cocoa beans

Step #3: Drying the cocoa seeds

After fermentation, the cocoa seeds must be dried before they can be scooped into sacks and shipped to chocolate manufacturers. Farmers simply spread the fermented seeds on trays and leave them in the sun to dry. The drying process usually takes about a week and results in seeds that are about half of their original weight.

The dried and roasted Cocoa beans

Manufacturing Chocolate

Once the cocoa beans have reached the machinery of chocolate factories, they are ready to be refined into chocolate. Generally, manufacturing processes differ slightly due to the different species of cocoa trees, but most factories use similar machines to break down the cocoa beans into cocoa butter and chocolate (International Cocoa Organization, 1998). Firstly, fermented and dried cocoa beans will be refined to a roasted nib by winnowing and roasting. Then, they will be heated and will melt into chocolate liquor. Lastly, manufacturers blend chocolate liquor with sugar and milk to add flavour. After the blending process, the liquid chocolate will be stored or delivered to the molding factory in tanks and will be poured into moulds for sale. Finally, wrapping and packaging machines will pack the chocolates and then they will be ready to transport.

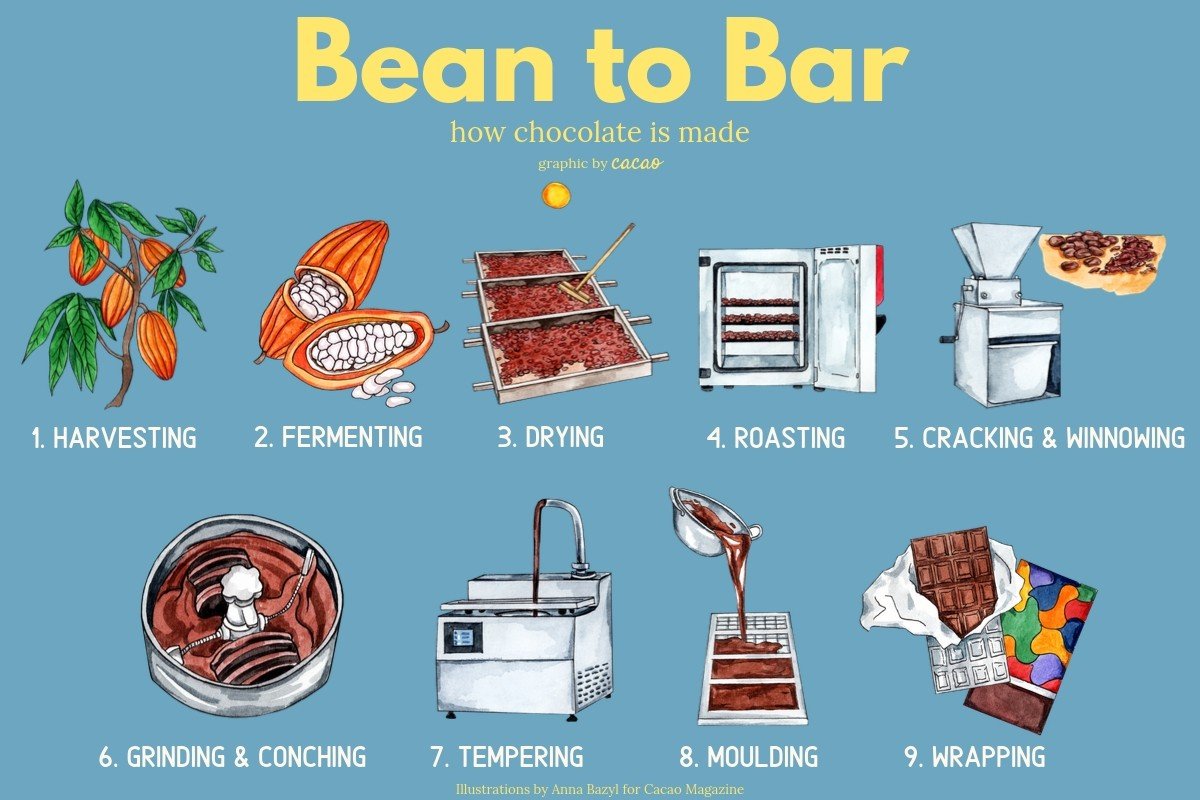

A diagram showing the manufacturing process:

Step #1: Roasting and Winnowing the Cocoa

The first thing that chocolate manufacturers do with cocoa beans is roast them. This develops the colour and flavour of the beans into what our modern palates expect from fine chocolate. The outer shell of the beans is removed, and the inner cocoa bean meat is broken into small pieces called «cocoa nibs.»

The roasting process makes the shells of the cocoa brittle, and cocoa nibs pass through a series of sieves, which strain and sort the nibs according to size in a process called «winnowing».

Step #2: Grinding the Cocoa Nibs

Grinding is the process by which cocoa nibs are ground into » cocoa liquor», which is also known as unsweetened chocolate or cocoa mass. The grinding process generates heat and the dry granular consistency of the cocoa nib is then turned into a liquid as the high amount of fat contained in the nib melts. The cocoa liquor is mixed with cocoa butter and sugar. In the case of milk chocolate, fresh, sweetened condensed or roller-dry low-heat powdered whole milk is added, depending on the individual manufacturer’s formula and manufacturing methods.

Step #3: Blending Cocoa liquor and molding Chocolate

After the mixing process, the blend is further refined to bring the particle size of the added milk and sugar down to the desired fineness. The Cocoa powder or ‘mass’ is blended back with the butter and liquor in varying quantities to make different types of chocolate or couverture. The basic blends with ingredients roughly in order of highest quantity first are as follows:

White Chocolate— sugar, milk or milk powder, cocoa liquor, cocoa butter, Lethicin and Vanilla.

After blending is complete, molding is the final procedure for chocolate processing. This step allows cocoa liquor to cool and harden into different shapes depending on the mold. Finally the chocolate is packaged and distributed around the world.

Top of Page

Introduction

Chocolate

Background

Chocolate, in all of its varied forms (candy bars, cocoa, cakes, cookies, coating for other candies and fruits) is probably America’s favorite confection. With an annual per capita consumption of around 14 pounds (6 kilograms) per person, chocolate is as ubiquitous as a non-essential food can be.

Cocoa trees originated in South America’s river valleys, and, by the seventh century A.D., the Mayan Indians had brought them north into Mexico. In addition to the Mayans, many other Central American Indians, including the Aztecs and the Toltecs, seem to have cultivated cocoa trees, and the words «chocolate» and «cocoa» both derive from the Aztec language. When Cortez, Pizarro, and other Spanish explorers arrived in Central America in the fifteenth century, they noted that cocoa beans were used as currency and that the upper class of the native populations drank cacahuatl, a frothy beverage consisting of roasted cocoa beans blended with red pepper, vanilla, and water.

While the Spanish initially found the bitter flavor of unsweetened cacahuatl unpalatable, they gradually introduced modifications that rendered the drink more appealing to the European palate. Grinding sugar, cinnamon, cloves, anise, almonds, hazelnuts, vanilla, orange-flower water, and musk with dried cocoa beans, they heated the mixture to create a paste (as with many popular recipes today, variations were common). They then smoothed this paste on the broad, flat leaves of the plantain tree, let it harden, and removed the resulting slabs of chocolate. To make chocalatl, the direct ancestor of our hot chocolate, they dissolved these tablets in hot water and a thin corn broth. They then stirred the liquid until it frothed, perhaps to distribute the fats from the chocolate paste evenly (cocoa beans comprise more than fifty percent cocoa butter by weight). By the mid-seventeenth century, an English missionary reported that only members of Mexico’s lower classes still drank cacahuatl in its original form.

When missionaries and explorers returned to Spain with the drink, they encountered resistance from the powerful Catholic Church, which argued that the beverage, contaminated by its heathen origins, was bound to corrupt Christians who drank it. But the praise of returning conquistadors—Cortez himself designated chocalatl as «the divine drink that builds up resistance and fights fatigue»—overshadowed the church’s dour prophecies, and hot chocolate became an immediate success in Spain. Near the end of the sixteenth century, the country built the first chocolate factories, in which cocoa beans were ground into a paste that could later be mixed with water. Within seventy years the drink was prized throughout Europe, its spread furthered by a radical drop in the price of sugar between 1640 and 1680 (the increased availability of the sweetener enhanced the popularity of coffee as well).

Chocolate consumption soon extended to England, where the drink was served in «chocolate houses,» upscale versions of the coffee houses that had sprung up in London during the 1600s. In the mid-seventeenth century, milk chocolate was invented by an Englishman, Sir Hans Sloane, who had lived on the island of Jamaica for many years, observing the Jamaicans’ extensive use of chocolate. A naturalist and personal physician to Queen Anne, Sloane had previously considered the cocoa bean’s high fat content a problem, but, after observing how young Jamaicans seemed to thrive on both cocoa products and milk, he began to advocate dissolving chocolate tablets in milk rather than water.

The first Europeans to drink chocolate, the Spaniards were also the first to consume it in solid form. Although several naturalists and physicians who had traveled extensively in the Americas had noted that some Indians ate solid chocolate lozenges, many Europeans believed that consuming chocolate in this form would create internal obstructions. As this conviction gradually diminished, cook-books began to include recipes for chocolate candy. However, a typical eighteenth-century hard chocolate differed substantially from modern chocolate confections. Back then, chocolate candy consisted solely of chocolate paste and sugar held together with plant gums. In addition to being unappealing on its own, the coarse, crumbly texture of this product reduced its ability to hold sugar. Primitive hard chocolate, not surprisingly, was nowhere near as popular as today’s improved varieties.

These textural problems were solved in 1828, when a Dutch chocolate maker named Conrad van Houten invented a screw press that could be used to squeeze most of the butter out of cocoa beans. Van Houten’s press contributed to the refinement of chocolate by permitting the separation of cocoa beans into cocoa powder and cocoa butter. Dissolved in hot liquid, the powder created a beverage far more palatable than previous chocolate drinks, which were much like blocks of unsweetened baker’s chocolate melted in fluid. Blended with regular ground cocoa beans, the cocoa butter made chocolate paste smoother and easier to blend with sugar. Less than twenty years later, an English company introduced the first commercially prepared hard chocolate. In 1876 a Swiss candy maker named Daniel Peter further refined chocolate production, using the dried milk recently invented by the Nestle company to make solid milk chocolate. In 1913 Jules Sechaud, a countryman of Peter’s, developed a technique for making chocolate shells filled with other confections. Well before the first World War, chocolate had become one of the most popular confections, though it was still quite expensive.

Hershey Foods, one of a number of American chocolate-making companies founded during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, made chocolate more affordable and available. Today the most famous—although not the largest—chocolate producer in the United States, the company was founded by Milton Hershey, who invested the fortune he’d amassed making caramels in a Pennsylvania chocolate factory. Hershey had first become fascinated by chocolate at the 1893 Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition, where one of leading attractions was a 2,200-pound (998.8 kilograms), ten-foot (3.05 meters) tall chocolate statue of Germania, the symbol of the Stollwerck chocolate company in Germany (Germania was housed in a 38-foot [11.58 meters] Renaissance temple, also constructed entirely of chocolate). When he turned to chocolate making, Hershey decided to use the same fresh milk that had made his caramels so flavorful. He also dedicated himself to utilizing mass production techniques that would enable him to sell large quantities of chocolate, individually wrapped and affordably priced. For decades after Hershey began manufacturing them in 1904, Hershey bars cost only a nickel.

Another company, M&M/Mars, has branched out to produce dozens of non-chocolate products, thus making the company four times as large as Hershey Foods, despite the fact that the latter firm remains synonymous with chocolate in the eyes of many American consumers. Yet since its founding in 1922, M&M/Mars has produced many of the country’s most enduringly popular chocolate confections. M&M/Mars’ success began with the Milky Way bar, which was cheaper to produce than pure chocolate because its malt flavor derived from nougat, a mixture of egg whites and corn syrup. The Snickers and Three Musketeers bars, both of which also featured cost-cutting nougat centers, soon followed, and during the 1930s soldiers fighting in the Spanish Civil War suggested the M&M. To prevent the chocolate candy they carried in their pockets from melting, these soldiers had protected it with a sugary coating that the Mars company adapted to create its most popular product.

Raw Materials

Although other ingredients are added, most notably sugar or other sweeteners, flavoring agents, and sometimes potassium carbonate (the agent used to make so-called dutch cocoa), cocoa beans are the primary component of chocolate.

Cocoa trees are evergreens that do best within 20 degrees of the equator, at altitudes of between 100 (30.48 centimeters) and 1,000 (304.8 centimeters) feet above sea level. Native to South and Central America, the trees are currently grown on commercial plantations in such places as Malaysia, Brazil, Ecuador, and West Africa. West Africa currently produces nearly three quarters of the world’s 75,000 ton annual cocoa bean crop, while Brazil is the largest producer in the Western Hemisphere.

Because they are relatively delicate, the trees can be harmed by full sun, fungi, and insect pests. To minimize such damage, they are usually planted with other trees such as rubber or banana. The other crops afford protection from the sun and provide plantation owners with an alternative income if the cocoa trees fail.

The pods, the fruit of the cocoa tree, are 6-10 inches (15.24-25.4 centimeters) long and 3-4 inches (7.62-10.16 centimeters) in diameter. Most trees bear only about 30 to 40 pods, each of which contains between 20 and 40 inch-long (2.54 centimeters) beans in a gummy liquid. The pods ripen in three to four months, and, because of the even climate in which the trees grow, they ripen continually throughout the year. However, the greatest number of pods are harvested between May and December.

Of the 30 to 40 pods on a typical cacao tree, no more than half will be mature at any given time. Only the mature fruits can be harvested, as only they will produce top quality ingredients. After being cut from the trees with machetes or knives mounted on poles (the trees are too delicate to be climbed), mature pods are opened on the plantation with a large knife or machete. The beans inside are then manually removed.

Still entwined with pulp from the pods, the seeds are piled on the ground, where they are allowed to heat beneath the sun for several days (some plantations also dry the beans mechanically, if necessary). Enzymes from the pulp combine with wild, airborne yeasts to cause a small amount of fermentation that will make the final product even more appetizing. During the fermenting process, the beans reach a temperature of about 125 degrees Fahrenheit (51 degrees Celsius). This kills the embryos, preventing the beans from sprouting while in transit; it also stimulates decomposition of the beans’ cell walls. Once the beans have sufficiently fermented, they will be stripped of the remaining pulp and dried. Next, they are graded and bagged in sacks weighing from 130 to 200 pounds (59.02-90.8 kilograms). They will then be stored until they are inspected, after which they will be shipped to an auction to be sold to chocolate makers.

The Manufacturing

Process

Roasting, hulling, and crushing the beans

Making cocoa powder

Making chocolate candy

Quality Control

Proportions of ingredients and even some aspects of processing are carefully guarded secrets, although certain guidelines were set by the 1944 Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Law, as well as more recent laws and regulations. For example, milk chocolate must contain a minimum of 12 percent milk solids and 10 percent chocolate liquor. Sweet chocolate, which contains no milk solids, must contain at least fifteen percent chocolate liquor. The major companies, however, have a reputation for enforcing strict quality and cleanliness standards. Milton Hershey zealously insisted upon fresh ingredients, and the Mars company boasts that its factory floors harbor fewer bacteria than the average kitchen sink. Moreover, slight imperfections are often enough to prompt the rejection of entire batches of candy.

The Future

Although concerns about the high fat and caloric content of chocolate have reduced per capita consumption in the United States from over twenty pounds (9.08 kilograms) per year to around fourteen (6.36 kilograms), chocolate remains the most popular type of confection. In addition, several psychiatrists have recently speculated that, because the substance contains phenylethylamine, a natural stimulant, depressed people may resort to chocolate binges in an unknowing attempt to raise their spirits and adjust their body chemistry. Others have speculated that the substance exerts an amorous effect. Despite reduced levels of consumption and regardless of whether or not one endorses the various theories about its effects, chocolate seems guaranteed to remain what it has been throughout the twentieth century: a perennial American favorite.

Where To Learn More

Books

Chocolate Manufacturers’ Association of the U.S.A. The Story of Chocolate.

Hirsch, Sylvia Balser and Morton Gill Clark. A Salute to Chocolate. Hawthorn Books, 1968.

O’Neill, Catherine. Let’s Visit a Chocolate Factory. Troll Associates, 1988.

Periodicals

Cavendish, Richard. «The Sweet Smell of Success,» History Today. July, 1990, pp. 2-3.

«From Xocoatl to Chocolate Bars,» Consumer Reports. November, 1986, pp. 696-701.

Galvin, Ruth Mehrtens. «Sybaritic to Some, Sinful to Others, but How Sweet it Is!» Smithsonian. February, 1986, pp. 54-64.

Marshall, Lydia and Ethel Weinberg. «A Fine Romance,» Cosmopolitan. February, 1989, pp. 52-4.

ELTEC English

Teaching IELTS Students.

IELTS Academic Process Diagram: Chocolate Production

A Student’s answer correction:

The illustration shows how chocolate is produced.

Summarize the information by selecting and reporting main features, and make comparisons where relevant.

20 minutes, 150 words at least.

147 words. A well-written answer. Very few mistakes. Could have written better with some rephrasing. I’ve given examples below. BANDS: 7.0

The diagram explains the process of chocolate production. Overall, it can be seen that there are a total of ten stages of producing the chocolate, beginning with their (What does “their” refer to? Chocolate? Chocolate does not grow on cocoa trees.) growth on the trees and ending up with production process of the chocolate.

Rephrase in one sentence: The given diagram explains the process of chocolate manufacturing in ten stages from the growth of ripe red pods on cocoa trees to the production of liquid chocolate.

First of all, the cacao trees are grown in South America and Africa continents and Indonesia. Once the pods are ripe and red, they are harvested and the white cacao beans are extracted from it.

Please feel free to ask any questions in the comments section.

Follow this blog for more such exciting IELTS and PTE essays and like our Facebook Page. Let’s crack English language exams. You can contact us here.

Bean to Bar: How Chocolate is Made

F rom harvesting to wrapping, chocolate-making is an intricate and refined process that can be manipulated throughout certain stages for the purpose of achieving a particular flavour or texture. The evolved and meticulous process from bean to bar is reflected in the unique and delicious taste that comes from an exceptional plant. In this 9 step process, we will walk you through how chocolate is made.

1. Harvesting

The cacao tree (Theobroma cacao) grows in tropical climates throughout the world, and has the unusual trait of having both flowers and fruit on the tree at the same time. The fruit of the tree is known as the cacao pod, which grows on the trunk and branches. Each pod ripens at a different time, so expertise is needed in choosing the right time to pick the pod. Picking is usually done with a machete, and great care is needed to ensure that the flower cushion on the tree is not damaged so that more pods can grow in the future.

2. Fermenting

After the pods are opened and the beans are exposed to oxygen, the fermentation begins. The beans and pulp may be contained in banana leaves or wooden boxes, which contain holes for excess liquid to escape. The beans are mixed or turned to enable this process and the temperature naturally raises to 40-50°C. This stage is a major factor in developing the cacao flavour and can take up to eight days, depending on the bean type.

3. Drying

Following the fermentation stage, the beans contain a high level of moisture, which needs to be reduced in order to avoid overdeveloping, which can adversely affect the flavour. In most origins, cocoa beans can be sun-dried. In wetter climates, however, this is not possible so alternative methods are used. For example, in Papua New Guinea, beans are dried using open fires, giving them a distinctly smoky flavour. Once dried, the beans are then sorted and bagged, before being shipped to makers around the world.

4. Roasting

The next step is for chocolate-makers to roast their dried cacao beans. The roasting time and temperature will vary by bean type and quality, as well as the objectives of the chocolate-maker. In addition to being an important factor for flavour development, the roasting process also further reduces the moisture content and kills off any lurking bacteria.

5. Cracking & Winnowing

Following the roasting process, the outer shell becomes thin and brittle. The beans are then cracked manually or with a machine, after which the shells can be winnowed from the bean kernels, also known as cocoa nibs. The cocoa nibs are used in the production of chocolate, whereas the antioxidant-packed shells can be used for other purposes, such as making cacao tea or even garden fertiliser.

6. Grinding & Conching

These two processes are commonly combined into one with the use of a melangeur. First, the nibs are ground into a thick paste known as cocoa mass. This paste consists of both cocoa solids and cocoa butter, the natural fat of the cocoa bean. During the conching stage, some chocolate-makers add extra ingredients such as sugar, milk or vanilla. This step may take anything from two hours to two days, and the particulars of the process are crucial as they will affect the final texture and flavour.

7. Tempering

This is the process of raising and lowering the temperature of the chocolate so that it is formed into the right consistency through the treatment of the crystals. Without tempering, the chocolate would be dull and crumbly, missing the tempting shine and recognisable snap of a finished chocolate bar. This is traditionally done by hand but the process can also be sped up with a tempering machine.

8. Moulding

Once tempered, the melted chocolate is poured into the chosen mould and tapped against a hard surface to remove air bubbles. Craft chocolate-makers often do this by hand, while for larger manufacturers the process is mechanised for efficiency.

9. Wrapping

After the chocolate has cooled and solidified it is inspected for quality control. The final bar is then carefully wrapped in foil or paper packaging to keep it fresh, and labelled with a best before date and ingredients list. After the long journey from bean-to-bar, the chocolate is finally ready to be enjoyed!

If you’re interested in learning more about chocolate, then grab a copy of of Cacao Magazine where we discuss all things craft chocolate!

How chocolate is produced

This is another example of an IELTS task 1 process.

This is a fairly simple example so it is good if you are new to processes. In the actual test it is likely to be a bit more difficult.

The important things to remember when you write about a process are:

You should spend about 20 minutes on this task .

The illustrations show how chocolate is produced.

Summarize the information by selecting and reporting the main features and make comparisons where relevant.

Write at least 150 words.

The diagram explains the process for the making of chocolate. There are a total of ten stages in the process, beginning with the growing of the pods on the cacao trees and culminating in the production of the chocolate.

To begin, the cocoa comes from the cacao tree, which is grown in the South American and African continents and the country of Indonesia.В Once the pods are ripe and red, they are harvested and the white cocoa beans are removed. Following a period of fermentation, they are then laid out on a large tray so they can dry under the sun.

Next, they are placed into large sacks and delivered to the factory. They are then roasted at a temperature of 350 degrees, after which the beans are crushed and separated from their outer shell. In the final stage, this inner part that is left is pressed and the chocolate is produced.

Comments

The process starts with a good introduction that introduces the diagram and then gives an overview.

The task 1 process is clearly organised as it goes through each stage in turn.

It uses the passive voice as well, which you should use for a process diagram, as you are not saying who is doing the action.

Here is a lesson on decribing a process if you need more help.