How important is age as a factor in learning

How important is age as a factor in learning

Age and language learning

Рубрика: Филология, лингвистика

Дата публикации: 30.05.2016 2016-05-30

Статья просмотрена: 59 раз

Библиографическое описание:

Аминова, Н. И. Age and language learning / Н. И. Аминова. — Текст : непосредственный // Молодой ученый. — 2016. — № 11 (115). — С. 1634-1636. — URL: https://moluch.ru/archive/115/30606/ (дата обращения: 14.08.2022).

Статья посвящена для роли возраста и отдельных особенностей в изучении иностранного языка. Работа выполнена с некоторыми теориями и мыслями известных лингвистов. Актуальность темы заключается в том, что она создаёт способы для раскрытия высокой степени обучения иностранного языка и для дальнейшего развития обучающих методов, которые спорны.

Ключевые слова: L2 (второй язык), возраст, взрослый ученик, техника, способность изучения, физический фактор, превосходство.

There are some people who have a knack for learning second languages and others who are rather poor at it. Some immigrants who have been in a country for twenty years are very fluent. Others from the same background and living in the same circumstances for the same amount of time speak the language rather poorly. So all are the same but why are there such differences? Differences in second language learning ability are apparently only felt in societies where second language learning is treated as a problem rather than accepted as an every-day fact of life.

As we see, children are believed to be better at learning second languages than adults. Most of us know a friend or acquaintance who started learning English as an adult and never managed to learn it properly, and another who learnt it as a child and is indistinguishable from a native speaker. Linguists as well as the general public often share this point of view. Chomsky has talked of the immigrant child learning a language quickly, while “the subtleties that become second nature to the child may elude his parents despite high motivation and continued practice”. Most people prove this annually. They start the year by worrying whether their children will ever cope with English, and they end it by complaining how much better the children speak than themselves. This belief in the superiority of young learners was enshrined in the critical period hypothesis: the claim that human beings are only capable of learning their first language between the age of two years and the early teens. A variety of explanations have been put forward for the apparent decline in adults: physical factors such as the loss of ‘plasticity’ in the brain and ‘lateralization’ of the brain; social factors such as the different situations and relationships that children encounter compared to adults; and cognitive explanations such as the interference with natural language learning by the adult’s more abstract mode of thinking. It has often been concluded that learning any foreign language should be started as early as possible. Indeed, the 1990s saw a growth in the UK in ‘bilingual’ playgroups, teaching French to English-speaking children under the age of 5. Much research, on the contrary, shows that age is a positive advantage. English-speaking adults and children who had gone to live in Holland were compared using a variety of tests. At the end of three months, the older learners were better at all aspects of Dutch except pronunciation. After a year this advantage had faded and the older learners were better only at vocabulary. Studies in Scandinavia showed that Swedish children improved at learning English throughout the school years, and Finnish-speaking children under 11 learning Swedish in Sweden were worse than those over 11. Although the total physical response method of teaching, with its emphasis on physical action, appears more suitable to children, when it was used for teaching Russian to adults and children the older students were consistently better. If children and adults are compared who are learning a second language in exactly the same way, whether as immigrants to Holland, or by the same method in the classroom, adults are better. Age itself is not so important as the different interactions that learners of different ages have with the situation and with other people. De Keyser and Larson-Hall found a negative correlation with age in ten research studies into age of acquisition that is, older learners tend to do worse. Usually children are thought to be better at pronunciation in particular. The claim is that an authentic accent cannot be acquired if the second language is learnt after a particular age, say the early teens. For instance, the best age for Cuban immigrants to come to the USA so far as pronunciation is concerned is under 6, the worst over 13. Ramsey and Wright found younger immigrants to Canada had less foreign accent than older ones. But the evidence mostly is not clear-cut. Indeed, Ramsey and Wright’s evidence has been challenged by Cummins. Other research shows that when the teaching situation is the same, older children are better than younger children even at pronunciation. An experiment with the learning of Dutch by English children and adults found imitation was more successful with older learners. David Singleton sums up his authoritative review of age with the statement:

The one interpretation of the evidence which does not appear to run into contradictory data is that in naturalistic situations those whose exposure to a second language begins in childhood in general eventually surpass those whose exposure begins in adulthood, even though the latter usually show some initial advantage over the former.

A related question is whether the use of teaching methods should vary according to the age of the students. At particular ages students prefer particular methods. Teenagers may dislike any technique that exposes them in public; role play and simulation are in conflict with their adolescent anxieties. Adults can feel they are not learning properly in play-like situations and prefer a conventional, formal style of teaching. Adults learn better than children from the ‘childish’ activities of total physical response — if you can get them to join in. Age is by no means crucial to L2 learning itself. Spolsky describes three conditions for L2 learning related to age:

Thinking type and age as factors influencing the learning of English by adults and children

Рубрика: Филология, лингвистика

Дата публикации: 11.12.2021 2021-12-11

Статья просмотрена: 5 раз

Библиографическое описание:

Осипова, С. Д. Thinking type and age as factors influencing the learning of English by adults and children / С. Д. Осипова, А. И. Шкитина. — Текст : непосредственный // Молодой ученый. — 2021. — № 50 (392). — С. 616-619. — URL: https://moluch.ru/archive/392/86706/ (дата обращения: 14.08.2022).

The purpose of this article is to prove that a person’s age does not affect the actual ability to learn (more specifically, to acquire knowledge of the English language), but only the way of perception and assimilation of this knowledge, their level. It also considers the theory that childhood, the period of initial physical and mental development, corresponds to intuitive thinking and approach to learning, while a mature person strives for analytical thinking and the most complete understanding of new information. The paper presents the results of a survey and a test, created for proving the existence between factors such as the age of onset of language, type of thinking and level of knowledge, as well as an analysis of the data obtained.

Keywords: foreign language, English, learning, analytical thinking, intuitive thinking, education, learning, adults, children, The Critical Period Hypothesis, Sensitive period.

Цель данной статьи — доказать, что возраст человека не влияет на фактическую способность к приобретению новых знаний (конкретнее, знание английского языка), а лишь на способ восприятия и усвоение этих знаний, их уровень. Также рассматривается теория о том, что детский возраст, т. е. период начального физического и психического развития, соответствует интуитивному мышлению и подходу к обучению, в то время как зрелый человек стремится к аналитическому мышлению и максимально полному пониманию новой информации. В работе представлены результаты опроса и теста, созданных для доказательства существования связи между такими факторами, как возраст начала изучения языка, тип мышления и уровень знаний, а также анализ полученных данных.

Ключевые слова: иностранный язык, английский язык, изучение, аналитическое мышление, интуитивное мышление, образование, обучение, взрослые, дети, гипотеза критического периода, сензитивный период.

Among the people of the older generation who aim to learn a particular foreign language, there is a stereotype that mastering a new language is impossible for them. Most often, this position is supported by an argument connected to older age and the belief that the possibility to acquire knowledge of a foreign language exists only in childhood. Such a stereotype most likely developed due to the omission of the fact of the typology of thinking and its dependence on the age of the subject, namely, the existence of intuitive and analytical, per se logical, thinking. This study explains the difference between the two types of thinking and correlates them with the age of the subject of learning a foreign language with the following study of the influence of the mentioned factors on the level of language. The main goal of this work is to prove the existence of a connection between the age of the subject of learning a foreign language, their type of thinking, corresponding to the age and the level of knowledge acquired . The method of the study is based on the comparative analysis of the process of thinking of a child and an adult while learning foreign language, focusing on English, and comparison of their results in practical usage of received knowledge. The article is divided into the following sections: literary review, research methods, key results and discussion, conclusion and references.

Literature review

While there are different opinions on the question of dependence of the language learners’ age on ability to acquire some language skills, this factor appears to be in the interest not only of the students, but educators (Jasmina Murad, 2006). One more not less significant issue that is the object of teachers’ attention is the best period for learners to begin their way to the second language. This section of the paper observes the biological perspective of the theme basing on the The Critical Period Hypothesis, moving on to the psychological aspect of Sensitive period and, finally, provides information about intuitive and analytical thinking.

As neurologist Eric Lenneberg (1967) formulated The Critical Period Hypothesis, it is stated that the brain of a child is more plastic, while an adult’s one is already rigid and set. What is meant by «plastic» is that the language is perceived by both brain hemispheres, but this process becomes a function of only the left hemisphere with age. According to The CPH, this period starts at the age of 2 and lasts until puberty, meaning 12–13 years old. At the same time, this does not negate the ability to learn language after this period, but the process is transformed.

There is the observation of psychological and biological phenomena significant for the presented theme, as well as two types of thinking and correlation to ontogenesis. The following practical part is going to test the described theory in terms of learning English as the second language on different stages of ontogenesis and corresponding thinking development level.

Research methods

The research consists in one large-scale survey divided into 3 parts. The first part focuses on the collection of basic information as the age of starting to learn English and language level. The next one is in the format of a test ordered to count the points gathered by a respondent by completing the tasks on listening, reading, grammar and vocabulary. Each section includes at least 2 tasks with different difficulty levels. The last section is based on Likert scale and suggests a self-assessment of the test passing process.

Key results and Discussion

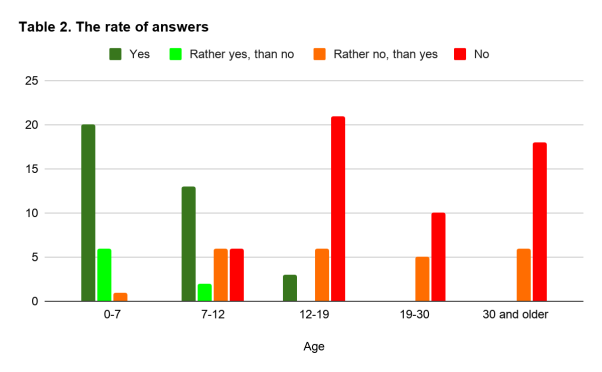

The practical part was created in the form of a questionnaire with three sections. The key question (except for questions on basic information) of the first part is «At what age did you start learning English?». To answer, 5 age categories are suggested. The following section is a test with a maximum score of 40 points. The last section consists of 3 statements with evaluating options. Each statement evaluates the process of the test and an answer helps to recognize the predominant thinking type involved in the test solution. The statements are structured in such a way that the answers «Yes» and «Rather yes than no» imply the inclusion of intuitive thinking, and «No» and «Rather no than yes» — analytical. Thus, the prevalence of one or another answer approximately determines the type of thinking.

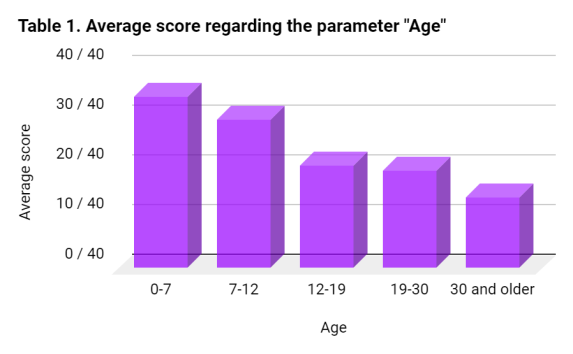

Firstly, the connection between the age of the beginning of learning English language and the average score among respondents is to be observed.

Furthermore, the connection between the results, the age and the type of thinking is to be analysed. The table 2 presents the rate of positive answers corresponding with the intuitive type and negative with rational and analytical one. According to table 2, the next relation is noted: the younger respondents are, the higher rate of «yes» and «rather yes, than no» answers are shown and contrariwise.

The last third section suggests a respondent to evaluate the process of the test and was based on Likert scale. The scale allows to evaluate the degree of agreement with the presented statements. It was stated that the earlier age corresponds to the prevalence of intuitive type of thinking and learning, respectively, meaning that a respondent did not feel the necessity to remember the certain rule, discomfort due to the unknown words and completed the tasks faster. According to table 2, the next relation is noted: the younger respondents are, the higher rate of «yes» and «rather yes, than no» answers are shown and contrariwise.

Conclusion

Taking all the presented and discussed information into consideration, the results of the practical part allow to conclude that there is a connection between such factors as the age of onset of language and type of thinking, together influencing the learners’ language level. At the same time, the earlier age is claimed to be the most propper not denying the older age as a period of impossibility of learning language.

The age factor in second language acquisition

Is there an optimal age for second language acquisition? Everybody agrees that age is a crucial factor in language learning. However to which extent age is an important factor still remains an open question. A plethora of elements can influence language learning: biological factors, mother tongue, intelligence, learning surroundings, emotions, motivation and last but not least: the age factor.

Lenneberg´s critical period hypothesis (1967) suggests that there is a biologically determined period of life when language can be acquired more easily. Beyond this time a language is more difficult to acquire. According to Lenneberg, bilingual language acquisition can only happen during the critical period (age 2 to puberty). The critical period hypothesis is associated with neurophysiological mechanisms suggesting that in late bilinguals the early and the late acquired languages are represented in spatially separated parts of the brain (Broca’s area). In early bilinguals, however, a similar activation in Broca’s area takes place for both languages. This loss of the brain´s plasticity explains why adults may need more time and effort compared to children in second language learning.

The advantages of early second language acquisition

In early childhood, becoming bilingual is often an unconscious event, as natural as learning to walk or ride a bicycle. But why? According scientific surveys, language aspects such as pronunciation and intonation can be acquired easier during childhood, due to neuromuscular mechanisms which are only active until to the age of 12. Another possible explanation of children’s accent-free pronunciation is their increased capability for imitation. This capability fades away significantly after puberty. Other factors that we should take into consideration are children’s flexibility, spontaneity and tolerance to new experiences. Kids are more willing to communicate with people than adults, they are curious and they are not afraid of making mistakes. They handle difficulties (such as missing vocabulary) very easily by using creative methods to communicate, such as non-verbal means of communication and use of onomatopoetic words. Also the idea of a foreign civilisation is not formed in their minds yet. Only at the age of 8 does it become clear to them that there are ethnic and cultural differences. Last but not least, aspects such as time, greater learning and memory capacity are in any case advantages in early language learning. On the other hand there are surveys which point out the risk of semi-lingualism and advise parents to organise language planning carefully.

The advantages of late second language acquisition

First of all it is important to clarify that by late second language learning we mean learning a language after puberty. Linguists, psychologists and pedagogues have been struggling for years to answer the following question: is it possible to reach native-like proficiency when learning a language after puberty? In order to give an answer we have to consider the following factors: First of all, adults (meaning people after puberty) have an important advantage: cognitive maturity and their experience of the general language system. Through their knowledge of their mother tongues, as well as other foreign languages, not only can they achieve more advantageous learning conditions than children, but they can also more easily acquire grammatical rules and syntactic phenomena. According to Klein Dimroth (see references), language learning is an accumulative process that allows us to build on already existing knowledge. Children cannot acquire complex morphological and grammatical phenomena so easily.

It would be useful to point out that sometimes incorrect pronunciation is not a matter of capability but of good will. According to different surveys, adults do not feel like themselves when they speak a foreign language and they consider pronunciation an ethno-linguistic identity-marker. A positive or negative attitude towards a foreign language should not be underestimated. Another factor to consider is the adults’ motivation to learn a foreign language. When an adult learns a foreign language there is always a reason behind it: education, social prestige, profession or social integration. The latter is considered a very strong one, especially in the case of immigrants.

Conclusion

It is obvious that the language learning processes in adults and children have advantages and disadvantages. However, age is an important but not overriding factor. All people, regardless of age, perceive a language learning process differently and individually. Personality and talent can influence this process significantly: there are shy children and very communicative adults. My (the author’s) conclusion? It is advisable to encourage language learning at an early age. The younger the child is, the more they can take advantage of neuromuscular mechanisms that promote language learning and thus reach a native-like level with less effort and time. Other advantages, such as increased communication abilities, better articulation, tolerance to foreign cultures and personal cognitive development, are among the benefits of early language learning. Yet this does not exclude effective language learning in adults. Under ideal learning situations, with motivation and a positive attitude, everybody can reach an excellent language level!

Written by Katerina Karavasili, translator and Master´s student of German as a foreign language (2014). Former TermCoord Communication Trainee.

Post edited by Doris Fernandes del Pozo – Journalist, Translator-Interpreter and Communication Trainee at the Terminology Coordination Unit of the European Parliament. She is pursuing a PhD as part of the Communication and Contemporary Information Programme of the University of Santiago de Compostela (Spain).

Age and Language Learning

The following two reports were sponsored by the US Department of Education and show the effect of age and language learning from two different perspectives. The Older Language Learner shows some of the myths surrounding adult language learners, and Myths and Misconceptions about Second Language Learning shows the same from the perspective of working with children. These reports were produced mainly for teachers and educators, but they clearly show that people of any age can be accomplished language learners, particularly self-motivated adults. In addition, they show how learning style and different learning methods can have a powerful impact on our success rate as language learners.

The Older Language Learner

Can older adults successfully learn foreign languages? Recent research is providing increasingly positive answers to this question. The research shows that:

—there is no decline in the ability to learn as people get older;

—except for minor considerations such as hearing and vision loss, the age of the adult learner is not a major factor in language acquisition;

—the context in which adults learn is the major influence on their ability to acquire the new language.

Contrary to popular stereotypes, older adults can be good foreign language learners. The difficulties older adults often experience in the language classroom can be overcome through adjustments in the learning environment, attention to affective factors, and use of effective teaching methods.

AGING AND LEARNING ABILITY

The greatest obstacle to older adult language learning is the doubt—in the minds of both learner and teacher—that older adults can learn a new language. Most people assume that «the younger the better» applies in language learning. However, many studies have shown that this is not true. Studies comparing the rate of second language acquisition in children and adults have shown that although children may have an advantage in achieving native-like fluency in the long run, adults actually learn languages more quickly than children in the early stages (Krashen, Long, and Scarcella, 1979). These studies indicate that attaining a working ability to communicate in a new language may actually be easier and more rapid for the adult than for the child.

Studies on aging have demonstrated that learning ability does not decline with age. If older people remain healthy, their intellectual abilities and skills do not decline (Ostwald and Williams, 1981). Adults learn differently from children, but no age-related differences in learning ability have been demonstrated for adults of different ages.

OLDER LEARNER STEREOTYPES

The stereotype of the older adult as a poor language learner can be traced to two roots: a theory of the brain and how it matures, and classroom practices that discriminate against the older learner.

The «critical period» hypothesis that was put forth in the 1960’s was based on then-current theories of brain development, and argued that the brain lost «cerebral plasticity» after puberty, making second language acquisition more difficult as an adult than as a child (Lenneberg, 1967).

More recent research in neurology has demonstrated that, while language learning is different in childhood and adulthood because of developmental differences in the brain, «in important respects adults have superior language learning capabilities» (Walsh and Diller, 1978). The advantage for adults is that the neural cells responsible for higher-order linguistic processes such as understanding semantic relations and grammatical sensitivity develop with age. Especially in the areas of vocabulary and language structure, adults are actually better language learners than children. Older learners have more highly developed cognitive systems, are able to make higher order associations and generalizations, and can integrate new language input with their already substantial learning experience. They also rely on long-term memory rather than the short-term memory function used by children and younger learners for rote learning.

AGE RELATED FACTORS IN LANGUAGE LEARNING

Health is an important factor in all learning, and many chronic diseases can affect the ability of the elderly to learn. Hearing loss affects many people as they age and can affect a person’s ability to understand speech, especially in the presence of background noise. Visual acuity also decreases with age. (Hearing and vision problems are not restricted exclusively to the older learner, however.) It is important that the classroom environment compensate for visual or auditory impairments by combining audio input with visual presentation of new material, good lighting, and elimination of outside noise (Joiner, 1981).

Certain language teaching methods may be inappropriate for older adults. For example, some methods rely primarily on good auditory discrimination for learning. Since hearing often declines with age, this type of technique puts the older learner at a disadvantage.

Exercises such as oral drills and memorization, which rely on short-term memory, also discriminate against the adult learner. The adult learns best not by rote, but by integrating new concepts and material into already existing cognitive structures.

Speed is also a factor that works against the older student, so fast-paced drills and competitive exercises and activities may not be successful with the older learner.

HELPING OLDER ADULTS SUCCEED

Three ways in which teachers can make modifications in their programs to encourage the older adult language learner include eliminating affective barriers, making the material relevant and motivating, and encouraging the use of adult learning strategies.

Affective factors such as motivation and self-confidence are very important in language learning. Many older learners fear failure more than their younger counterparts, maybe because they accept the stereotype of the older person as a poor language learner or because of previous unsuccessful attempts to learn a foreign language. When such learners are faced with a stressful, fast-paced learning situation, fear of failure only increases. The older person may also exhibit greater hesitancy in learning. Thus, teachers must be able to reduce anxiety and build self-confidence in the learner.

Class activities which include large amounts of oral repetition, extensive pronunciation correction, or an expectation of error-free speech will also inhibit the older learner’s active participation. On the other hand, providing opportunities for learners to work together, focusing on understanding rather than producing language, and reducing the focus on error correction can build learners’ self-confidence and promote language learning. Teachers should emphasize the positive—focus on the good progress learners are making and provide opportunities for them to be successful. This success can then be reinforced with more of the same.

Older adults studying a foreign language are usually learning it for a specific purpose: to be more effective professionally, to be able to survive in an anticipated foreign situation, or for other instrumental reasons. They are not willing to tolerate boring or irrelevant content, or lessons that stress the learning of grammar rules out of context. Adult learners need materials designed to present structures and vocabulary that will be of immediate use to them, in a context which reflects the situations and functions they will encounter when using the new language. Materials and activities that do not incorporate real life experiences will succeed with few older learners.

Older adults have already developed learning strategies that have served them well in other contexts. They can use these strategies to their advantage in language learning, too. Teachers should be flexible enough to allow different approaches to the learning task inside the classroom. For example, some teachers ask students not to write during the first language lessons. This can be very frustrating to those who know that they learn best through a visual channel.

Older adults with little formal education may also need to be introduced to strategies for organizing information. Many strategies used by learners have been identified; these can be incorporated into language training programs to provide a full range of possibilities for the adult learner (Oxford-Carpenter, 1985).

An approach which stresses the development of the receptive skills (particularly listening) before the productive skills may have much to offer the older learner (Postovsky, 1974; Winitz, 1981; J. Gary and N. Gary, 1981). According to this research, effective adult language training programs are those that use materials that provide an interesting and comprehensible message, delay speaking practice and emphasize the development of listening comprehension, tolerate speech errors in the classroom, and include aspects of culture and non-verbal language use in the instructional program. This creates a classroom atmosphere which supports the learner and builds confidence.

Teaching older adults should be a pleasurable experience. Their self-directedness, life experiences, independence as learners, and motivation to learn provide them with advantages in language learning. A program that meets the needs of the adult learner will lead to rapid language acquisition by this group.

Author: Schleppegrell, Mary

Source: ERIC Clearinghouse on Languages and Linguistics Washington DC.

ERIC Identifier: ED287313

Publication Date: 1987-09-00

FOR MORE INFORMATION

Gary, J. O., and N. Gary. «Comprehension-based Language Instruction: From Theory to Practice.» ANNALS NEW YORK ACADEMY OF SCIENCES (1981): 332-352.

Joiner, E. G. THE OLDER FOREIGN LANGUAGE LEARNER: A CHALLENGE FOR COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES. (Language in Education Series No. 34). Washington, DC: ERIC Clearinghouse on Languages and Linguistics; available from Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1981. ED 208 672.

Krashen, S. D., M. A. Long, and R. C. Scarcella. «Age, Rate and Eventual Attainment in Second Language Acquisition.» TESOL QUARTERLY 13 (1979): 573-582.

Lenneberg, E. H. BIOLOGICAL FOUNDATIONS OF LANGUAGE. New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1967.

Ostwald, S. K., and H. Y. Williams. «Optimizing Learning in the Elderly: A Model.» LIFELONG LEARNING 9 (1985): 10-13, 27.

Oxford-Carpenter, R. «A New Taxonomy of Second Language Learning Strategies.» Washington, DC: ERIC Clearinghouse on Languages and Linguistics, 1985 (FL No. 015 798).

Postovsky, V. «The Effects of Delay in Oral Practice at the Beginning of Second Language Learning.» MODERN LANGUAGE JOURNAL 58 (1974): 229-239.

Walsh, T. M., and K. C. Diller. «Neurolinguistic Foundations to Methods of Teaching a Second Language.» INTERNATIONAL REVIEW OF APPLIED LINGUISTICS 16 (1978): 1-14.

Weisel, L. P. ADULT LEARNING PROBLEMS: INSIGHTS, INSTRUCTION, AND IMPLICATIONS. (Information Series No. 214.) Columbus, OH: ERIC Clearinghouse on Adult, Career, and Vocational Education, 1980. ED 193 534.

Winitz, H. THE COMPREHENSION APPROACH TO FOREIGN LANGUAGE INSTRUCTION. Rowley, MA: Newbury House, 1981.

Myths and Misconceptions about Second Language Learning

As the school-aged population changes, teachers all over the country are challenged with instructing more children with limited English skills. Thus, all teachers need to know something about how children learn a second language (L2). Intuitive assumptions are often mistaken, and children can be harmed if teachers have unrealistic expectations of the process of L2 learning and its relationship to the acquisition of other academic skills and knowledge.

As any adult who has tried to learn another language can verify, second language learning can be a frustrating experience. This is no less the case for children, although there is a widespread belief that children are facile second language learners. This digest discusses commonly held myths and misconceptions about children and second language learning and the implications for classroom teachers.

MYTH 1: CHILDREN LEARN SECOND LANGUAGES QUICKLY AND EASILY.

Typically, people who assert the superiority of child learners claim that children’s brains are more flexible (e.g., Lenneberg, 1967). Current research challenges this biological imperative, arguing that different rates of L2 acquisition may reflect psychological and social factors that favor child learners (Newport, 1990). Research comparing children to adults has consistently demonstrated that adolescents and adults perform better than young children under controlled conditions (e.g., Snow & Hoefnagel-Hoehle, 1978). One exception is pronunciation, although even here some studies show better results for older learners.

Nonetheless, people continue to believe that children learn languages faster than adults. Is this superiority illusory? Let us consider the criteria of language proficiency for a child and an adult. A child does not have to learn as much as an adult to achieve communicative competence. A child’s constructions are shorter and simpler, and vocabulary is smaller. Hence, although it appears that the child learns more quickly than the adult, research results typically indicate that adult and adolescent learners perform better.

Teachers should not expect miraculous results from children learning English as a second language (ESL) in the classroom. At the very least, they should anticipate that learning a second language is as difficult for a child as it is for an adult. It may be even more difficult, since young children do not have access to the memory techniques and other strategies that more experienced learners use in acquiring vocabulary and in learning grammatical rules.

Nor should it be assumed that children have fewer inhibitions than adults when they make mistakes in an L2. Children are more likely to be shy and embarrassed around peers than are adults. Children from some cultural backgrounds are extremely anxious when singled out to perform in a language they are in the process of learning. Teachers should not assume that, because children supposedly learn second languages quickly, such discomfort will readily pass.

MYTH 2: THE YOUNGER THE CHILD, THE MORE SKILLED IN ACQUIRING AN L2

Some researchers argue that the earlier children begin to learn a second language, the better (e.g., Krashen, Long, & Scarcella, 1979). However, research does not support this conclusion in school settings. For example, a study of British children learning French in a school context concluded that, after 5 years of exposure, older children were better L2 learners (Stern, Burstall, & Harley, 1975). Similar results have been found in other European studies (e.g., Florander & Jansen, 1968).

These findings may reflect the mode of language instruction used in Europe, where emphasis has traditionally been placed on formal grammatical analysis. Older children are more skilled in dealing with this approach and hence might do better. However, this argument does not explain findings from studies of French immersion programs in Canada, where little emphasis is placed on the formal aspects of grammar. On tests of French language proficiency, Canadian English-speaking children in late immersion programs (where the L2 is introduced in Grade 7 or 8) have performed as well or better than children who began immersion in kindergarten or Grade 1 (Genesee, 1987).

Pronunciation is one area where the younger-is-better assumption may have validity. Research (e.g., Oyama, 1976) has found that the earlier a learner begins a second language, the more native-like the accent he or she develops.

The research cited above does not suggest, however, that early exposure to an L2 is detrimental. An early start for «foreign» language learners, for example, makes a long sequence of instruction leading to potential communicative proficiency possible and enables children to view second language learning and related cultural insights as normal and integral. Nonetheless, ESL instruction in the United States is different from foreign language instruction. Language minority children in U.S. schools need to master English as quickly as possible while learning subject-matter content. This suggests that early exposure to English is called for. However, because L2 acquisition takes time, children continue to need the support of their first language, where this is possible, to avoid falling behind in content area learning.

Teachers should have realistic expectations of their ESL learners. Research suggests that older students will show quicker gains, though younger children may have an advantage in pronunciation. Certainly, beginning language instruction in Grade 1 gives children more exposure to the language than beginning in Grade 6, but exposure in itself does not predict language acquisition.

MYTH 3: THE MORE TIME STUDENTS SPEND IN A SECOND LANGUAGE CONTEXT, THE QUICKER THEY LEARN THE LANGUAGE.

Many educators believe children from non-English-speaking backgrounds will learn English best through structured immersion, where they have ESL classes and content-based instruction in English. These programs provide more time on task in English than bilingual classes. Research, however, indicates that this increased exposure to English does not necessarily speed the acquisition of English. Over the length of the program, children in bilingual classes, with exposure to the home language and to English, acquire English language skills equivalent to those acquired by children who have been in English-only programs (Cummins, 1981; Ramirez, Yuen, & Ramey, 1991). This would not be expected if time on task were the most important factor in language learning.

Researchers also caution against withdrawing home language support too soon and suggest that although oral communication skills in a second language may be acquired within 2 or 3 years, it may take 4 to 6 years to acquire the level of proficiency needed for understanding the language in its academic uses (Collier, 1989; Cummins, 1981).

Teachers should be aware that giving language minority children support in the home language is beneficial. The use of the home language in bilingual classrooms enables children to maintain grade-level school work, reinforces the bond between the home and the school, and allows them to participate more effectively in school activities. Furthermore, if the children acquire literacy skills in the first language, as adults they may be functionally bilingual, with an advantage in technical or professional careers.

MYTH 4: CHILDREN HAVE ACQUIRED AN L2 ONCE THEY CAN SPEAK IT.

Some teachers assume that children who can converse comfortably in English are in full control of the language. Yet for school-aged children, proficiency in face-to-face communication does not imply proficiency in the more complex academic language needed to engage in many classroom activities. Cummins (1980) cites evidence from a study of 1,210 immigrant children in Canada who required much longer (approximately 5 to 7 years) to master the disembedded cognitive language required for the regular English curriculum than to master oral communicative skills.

Educators need to be cautious in exiting children from programs where they have the support of their home language. If children who are not ready for the all-English classroom are mainstreamed, their academic success may be hindered. Teachers should realize that mainstreaming children on the basis of oral language assessment is inappropriate.

All teachers need to be aware that children who are learning in a second language may have language problems in reading and writing that are not apparent if their oral abilities are used to gauge their English proficiency. These problems in academic reading and writing at the middle and high school levels may stem from limitations in vocabulary and syntactic knowledge. Even children who are skilled orally can have such gaps.

MYTH 5: ALL CHILDREN LEARN AN L2 IN THE SAME WAY.

Most teachers would probably not admit that they think all children learn an L2 in the same way or at the same rate. Yet, this assumption seems to underlie a great deal of practice. Cultural anthropologists have shown that mainstream U.S. families and families from minority cultural backgrounds have different ways of talking (Heath, 1983). Mainstream children are accustomed to a deductive, analytic style of talking, whereas many culturally diverse children are accustomed to an inductive style. U.S. schools emphasize language functions and styles that predominate in mainstream families. Language is used to communicate meaning, convey information, control social behavior, and solve problems, and children are rewarded for clear and logical thinking. Children who use language in a different manner often experience frustration.

Social class also influences learning styles. In urban, literate, and technologically advanced societies, middle-class parents teach their children through language. Traditionally, most teaching in less technologically advanced, non-urbanized cultures is carried out nonverbally, through observation, supervised participation, and self-initiated repetition (Rogoff, 1990). There is none of the information testing through questions that characterizes the teaching-learning process in urban and suburban middle-class homes.

In addition, some children are more accustomed to learning from peers than from adults. Cared for and taught by older siblings or cousins, they learn to be quiet in the presence of adults and have little interaction with them. In school, they are likely to pay more attention to what their peers are doing than to what the teacher is saying.

Individual children also react to school and learn differently within groups. Some children are outgoing and sociable and learn the second language quickly. They do not worry about mistakes, but use limited resources to generate input from native speakers. Other children are shy and quiet. They learn by listening and watching. They say little, for fear of making a mistake. Nonetheless, research shows that both types of learners can be successful second language learners.

In a school environment, behaviors such as paying attention and persisting at tasks are valued. Because of cultural differences, some children may find the interpersonal setting of the school culture difficult. If the teacher is unaware of such cultural differences, their expectations and interactions with these children may be influenced.

Effective instruction for children from culturally diverse backgrounds requires varied instructional activities that consider the children’s diversity of experience. Many important educational innovations in current practice have resulted from teachers adapting instruction for children from culturally diverse backgrounds. Teachers need to recognize that experiences in the home and home culture affect children’s values, patterns of language use, and interpersonal style. Children are likely to be more responsive to a teacher who affirms the values of the home culture. CONCLUSION

Research on second language learning has shown that many misconceptions exist about how children learn languages. Teachers need to be aware of these misconceptions and realize that quick and easy solutions are not appropriate for complex problems. Second language learning by school-aged children takes longer, is harder, and involves more effort than many teachers realize.

We should focus on the opportunity that cultural and linguistic diversity provides. Diverse children enrich our schools and our understanding of education in general. In fact, although the research of the National Center for Research on Cultural Diversity and Second Language Learning has been directed at children from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds, much of it applies equally well to mainstream students.

Source: ERIC Clearinghouse on Languages and Linguistics Washington DC ERIC Identifier: ED350885

Publication Date: 1992-12-00

Collier, V. (1989). How long: A synthesis of research on academic achievement in a second language. «TESOL Quarterly, 23,» 509-531.

Cummins, J. (1980). The cross-lingual dimensions of language proficiency: Implications for bilingual education and the optimal age issue. «TESOL Quarterly, 14,» 175-187.

Cummins, J. (1981). The role of primary language development in promoting educational success for language minority students. In «Schooling and language minority students: A theoretical framework.» Los Angeles: California State University; Evaluation, Dissemination, and Assessment Center.

Florander, J., & Jansen, M. (1968). «Skolefors’g i engelsk 1959-1965.» Copenhagen: Danish Institute of Education.

Genesee, F. (1987). «Learning through two languages: Studies of immersion and bilingual education.» New York: Newbury House.

Heath, S. B. (1983). «Ways with words: Language, life, and work in communities and classrooms.» New York: Cambridge.

Krashen, S., Long, M., & Scarcella, R. (1979). Age, rate, and eventual attainment in second language acquisition. «TESOL Quarterly, 13,» 573-582.

Lenneberg, E. H. (1967). «The biological foundations of language.» New York: Wiley.

Newport, E. (1990). Maturational constraints on language learning. «Cognitive Science, 14,» 11-28.

Oyama, S. (1976). A sensitive period for the acquisition of nonnative phonological system. «Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 5,» 261-284.

Ramirez, J.D., Yuen, S.D., & Ramey, D.R. (1991). «Longitudinal study of structured English immersion strategy, early-exit and late-exit transitional bilingual education programs for language minority children. Final Report.» «Volumes 1 & 2.» San Mateo, CA: Aguirre International.

Rogoff, B. (1990). «Apprenticeship in thinking: Cognitive development in social context.» New York: Oxford.

Snow, C. E., & Hoefnagel-Hoehle, M. (1978). The critical period for language acquisition: Evidence from second language learning. «Child Development, 49,» 1114-1118.

Stern, H. H., Burstall, C., & Harley, B. (1975). «French from age eight or eleven?» Toronto: Ontario Institute for Studies in Education.

Would you prefer to share this page with others by linking to it?

Would you prefer to share this page with others by linking to it?

Language Teacher Toolkit: Steve Smith’s blog

News, views, reviews, lesson ideas, pedagogy since 2009

Search This Blog

The age factor in language learning

|

| Image: pixabay.com |

This post draws on a section from Chapter 5 of Jack C. Richards’ splendid handbook Key Issues in Language Teaching (2015). I’m going to summarise what Richards writes about how age factors affect language learning, then add my own comments about how this might influence classroom teaching.

It’s often said that children seem to learn languages so much more quickly and effectively than adults. Yet adults do have some advantages of their own, as we’ll see.

In the 1970s it was theorised that children’s success was down to the notion that there is a critical period for language learning (pre-puberty). Once learners pass this period changes in the brain make it harder to learn new languages. Many took this critical period hypothesis to mean that we should get children to start learning other languages at an earlier stage. (The claim is still picked up today by decision-makers arguing for the teaching of languages in primary schools.)

Unfortunately, large amounts of research on the hypothesis has failed to confirm it. We cannot say for sure that younger learners are better (e.g. Ortega, 2009; Dörnyei, 2009). It’s true that younger learners seem to cope more easily with pronunciation, whereas older learners usually maintain a «foreign accent» for many years. But other factors may explain why young children seem to learn a language with such apparent ease. In naturalistic settings young children are generally highly motivated to learn. They receive huge amounts of input at or above their level of knowledge as well as a vast amount of practice. Language learning at this stage is also rewarded by peer acceptance and the satisfaction of basic communicative needs. the same can’t be said for many older learners of languages in classrooms. As Dörnyei (2009) points out, a large range of factors is involved in successful second language acquisition. Age may not be the most important one. What’s more, there are recorded examples of unsuccessful child learning and successful adult learning.

Adults have the advantage in other respects. Older learners are good at vocabulary learning, for example and make use of different cognitive skills to young children. Adults can learn more analytically and reflectively. They can be more autonomous in their learning. They can learn and apply rules and patterns (and, to add, may have some very specific needs to motivate them, e.g. learning for a specific professional need).

How might these issues influence our classroom practice?

I tend to be a pragmatist on pedagogy and often find myself taking a middle road. My own experience in a secondary education setting over many years in England, suggested to me that we can take advantage of the possible advantages which both younger children and adults possess. Beginners aged around 11 or under can certainly be trained to pronounce very accurately and I think this should be one of a teacher’s a priority. My experience with adult evening classes confirms to me that older adults have genuine difficulty getting pronunciation right.

Despite the research which suggests that learners that grammar is not «teachable», i.e. learners acquire grammatical patterns in their own, to some extent predictable order (e.g. Dulay, Burt and Krashen, 1982), and that they develop their own «interlanguage»* (Selinker, 1972), I have to say that in a non ESL context, where students hear and see very little of the language being taught outside the classroom, then I didn’t feel that classes were immune to the order in which I taught grammatical structures. I am not convinced that secondary students acquire in the same order as young children. Having read a fair bit of literature over the years, my hunch is that the brain responds in complex ways to a whole range of input, some of it highly structured with rules given to help, some of it far more implicitly through general exposure.

So beyond the age of 11 or so I would also argue for significant «focus on form», but not so much that it overly reduces the amount of patterned input at the right level. Students often want to know how the language works and there is enough evidence around in the scholarly literature that students can make their explicit knowledge of the language implicit. Put another way, they can learn a pattern and practise it to the extent that it eventually becomes available for spontaneous use. Declarative knowledge can, to some degree at least, become procedural.

Context has to be taken into account. What are the aims of the class? What exam are you preparing for? What is the culture of the school? What are your own strengths as a teacher? (Many teachers, for no fault of their own, lack the linguistic skill to deliver lots of accurate, well-pronounced comprehensible input.) What are your students like? What is their aptitude for second language learning?

In sum, young children and adults share a natural ability to acquire languages, but each group has unique advantages. In secondary schools we can exploit all the available advantages to help our students succeed.

* An interlanguage is a version of the new language where a learner preserves some features of their first language, and may also overgeneralize some L2 writing and speaking rules.

Dörnyei, Z. (2009). The Psychology of Second Language Acquisition, Oxford: OUP.

Dulay, Burt and Krashen, S. (1982) Language Two, New York: OUP.

Ortega, L. (2009). Understanding Second Language Acquisition, London: Hodder.

Richards, J. (2015) Key Issues in Language Teaching, Cambridge; CUP.

Selinker, L. (1972), Interlanguage. International Review of Applied Linguistics, 10, 209–231.