How is that made

How is that made

how is that

1 how’s that

Then we could have a good chinwag over a cup of tea. How’s that? — А потом мы могли бы поболтать за чашкой чая. Ну как?

How was that. Tony? — Что ты сказал. Тони?

2 how about that

They are going to publish my novel. How about that? — Они хотят опубликовать мой роман. Так-то вот

3 how’s that?

4 how about that!

5 How about that!

6 how about that!

7 how about that?

8 how is that?

9 How is that?

10 How’s that?

11 how’s that?

12 how’s that?

13 how’s that for high etc

How’s that for high, guys? — Ну как, ништяк, ребята?

How’s that for rich? — Ну что, разве он не богач?

14 how is that for high?

15 how’s that etc for something

I drove a honey wagon in Hollywood for a year. How’s that for glamour? — Я целый год сидел за рулем передвижного туалета в Голливуде. Вот тебе и блеск славы, блин

17 how does that grab you?

18 how does that song go?

19 how does that statement tie in with what you said yesterday?

20 how fortunate that I have found you today

См. также в других словарях:

how’s that — /how zatˈ/ (cricket; sometimes written howzatˈ) The appeal of the fielding side to the umpire to give the batsman out • • • Main Entry: ↑how * * * how s that (again) informal : ↑what used to request that something be repeated or explained again… … Useful english dictionary

how about that? — how about that?/how do you like that?/spoken phrase used when you are referring to something that is very surprising, annoying, or exciting So I’m going to be your new boss. How about that? Thesaurus: ways of saying that you are surprised or… … Useful english dictionary

how\ about\ that — • how about that • what about that informal An expression of surprise, congratulation, or praise. When Jack heard of his brother s promotion, he exclaimed, How about that! Bill won the scholarship! What about that! … Словарь американских идиом

how’s that? — how so?/how’s that?/spoken phrase used for asking someone to explain the reason for the statement they have just made ‘If the dam is built, a lot of people will suffer.’ ‘How so?’ Thesaurus: ways of asking questions and making requestshyponym to… … Useful english dictionary

how’s that? — ► how s that? Cricket is the batsman out or not? (said to an umpire). Main Entry: ↑how … English terms dictionary

how about that — that is interesting, you don t say How about that! We ran ten kilometres! … English idioms

how’s that — 1. why. “I m glad I don t work in a store.” “How s that?” “Because I wouldn t want to have to deal with customers all day.” “If you were planning on looking at the place today, you may be disappointed.” “How s that?” 2. I do not understand. “What … New idioms dictionary

how’s that —

how’s that —

how’s\ that — informal What did you say? Will you please repeat that? I ve just been up in a balloon for a day and a half. How s that? the courthouse is on fire. How s that again? … Словарь американских идиом

how about that — or[what about that]

How Software Is Made?

Whenever you listen to the name software, one question comes in your mind, that is “how software is made and how the software development process happens? So you will get all the solutions to your questions in this article.

Now before going to software, first you have to understand what is the computer? Because all software is made to run on computers, so let’s take a look at a computer.

Computer:

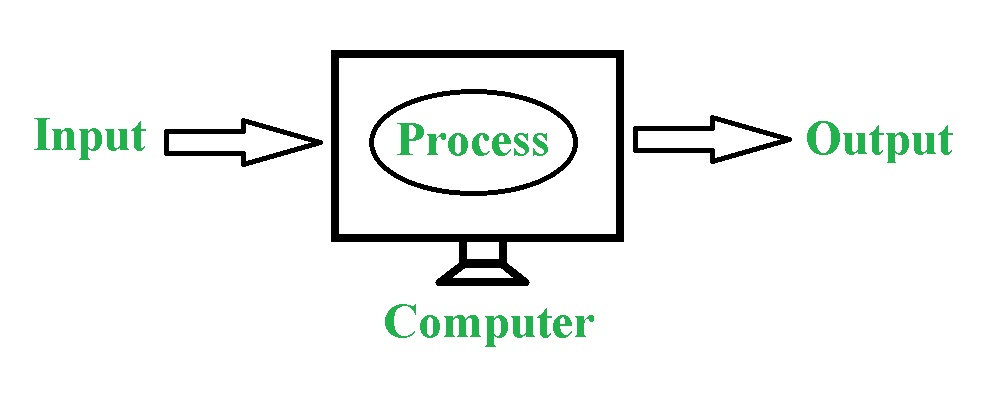

The computer is an electronic device that takes input process it and gives output.

To understand this computer let’s take one example: Suppose you are creating a document using MS-word, here Ms-word is the software and we give input from the keyboard, after giving input computer process it and show output to the screen. Now you get an idea that how the computer takes input then process it and gives output but, for this specific task that is creating a document, we need software like MS-word.

So the conclusion is we need software to perform the task on the computer.

Software:

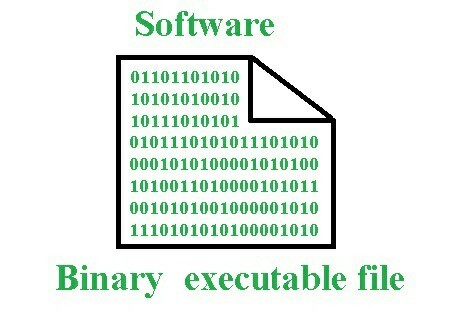

Software is a set of instructions instructing a computer to do specific tasks.

This set of instructions is also known as a program. These softwares which are running on the computer is in the form of binary code that is 1 and 0 which is an executable file as shown in the figure below.

As every task in the computer is done with the help of these programs the developer can change it as he wants by doing a program that’s why a computer is also called a programmable machine.

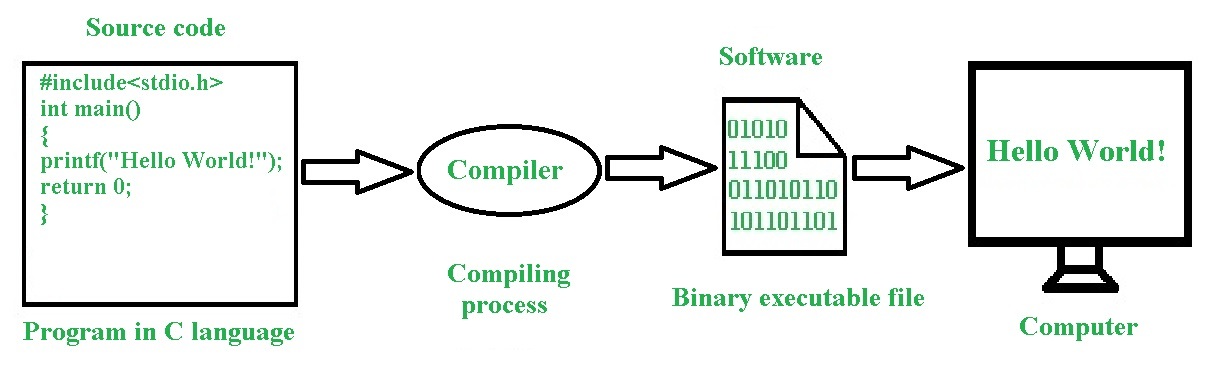

Writing the software in the form of binary is impossible and tedious hence, the engineers made various programming languages like C, C++, JAVA, Python, etc. Sometimes two or more languages are used for making one particular software.

How software is made?

Any program is written using any language that is understandable for a human is called source code and after making this source code with the help of the compiling process is converted into executable file. Here is one example of a basic C program source code converting into software as shown in the figure below.

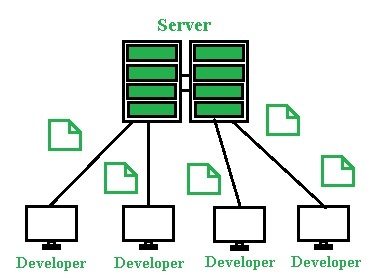

This simple program can be written by a developer in a reasonable amount of time however, professional software may involve hundreds of developers. A large software would be split up into hundreds or even thousands of files. one concept that allows them to do so is called revision control. So how it works?

As you can see in the above figure, all the source code for the software is stored on a server each developer stores a copy of these files on their machine. they can make changes to the server when they are ready. The server stores a detailed list of what files were changed? what those changes were and who submitted it. If any times the program gets into a bad state the developer can undo the changes until the software program is working correctly again.

Software developers work hard on their software but there are always a few problems with the code and we call these problems as a bugs. Even after a piece of software is released to the public, the software developers must continue to fix bugs and further improve the software. that is why software has updates or new versions that come out periodically.

The software can be created in two different ways: Proprietary, and Open source. These are explained as following below.

Types of Software:

What Google Learned From Its Quest to Build the Perfect Team

New research reveals surprising truths about why some work groups thrive and others falter.

Credit. Illustration by James Graham

Send any friend a story

As a subscriber, you have 10 gift articles to give each month. Anyone can read what you share.

Give this article

L ike most 25-year-olds, Julia Rozovsky wasn’t sure what she wanted to do with her life. She had worked at a consulting firm, but it wasn’t a good match. Then she became a researcher for two professors at Harvard, which was interesting but lonely. Maybe a big corporation would be a better fit. Or perhaps a fast-growing start-up. All she knew for certain was that she wanted to find a job that was more social. ‘‘I wanted to be part of a community, part of something people were building together,’’ she told me. She thought about various opportunities — Internet companies, a Ph.D. program — but nothing seemed exactly right. So in 2009, she chose the path that allowed her to put off making a decision: She applied to business schools and was accepted by the Yale School of Management.

When Rozovsky arrived on campus, she was assigned to a study group carefully engineered by the school to foster tight bonds. Study groups have become a rite of passage at M.B.A. programs, a way for students to practice working in teams and a reflection of the increasing demand for employees who can adroitly navigate group dynamics. A worker today might start the morning by collaborating with a team of engineers, then send emails to colleagues marketing a new brand, then jump on a conference call planning an entirely different product line, while also juggling team meetings with accounting and the party-planning committee. To prepare students for that complex world, business schools around the country have revised their curriculums to emphasize team-focused learning.

Every day, between classes or after dinner, Rozovsky and her four teammates gathered to discuss homework assignments, compare spreadsheets and strategize for exams. Everyone was smart and curious, and they had a lot in common: They had gone to similar colleges and had worked at analogous firms. These shared experiences, Rozovsky hoped, would make it easy for them to work well together. But it didn’t turn out that way. ‘‘There are lots of people who say some of their best business-school friends come from their study groups,’’ Rozovsky told me. ‘‘It wasn’t like that for me.’’

Instead, Rozovsky’s study group was a source of stress. ‘‘I always felt like I had to prove myself,’’ she said. The team’s dynamics could put her on edge. When the group met, teammates sometimes jockeyed for the leadership position or criticized one another’s ideas. There were conflicts over who was in charge and who got to represent the group in class. ‘‘People would try to show authority by speaking louder or talking over each other,’’ Rozovsky told me. ‘‘I always felt like I had to be careful not to make mistakes around them.’’

So Rozovsky started looking for other groups she could join. A classmate mentioned that some students were putting together teams for ‘‘case competitions,’’ contests in which participants proposed solutions to real-world business problems that were evaluated by judges, who awarded trophies and cash. The competitions were voluntary, but the work wasn’t all that different from what Rozovsky did with her study group: conducting lots of research and financial analyses, writing reports and giving presentations. The members of her case-competition team had a variety of professional experiences: Army officer, researcher at a think tank, director of a health-education nonprofit organization and consultant to a refugee program. Despite their disparate backgrounds, however, everyone clicked. They emailed one another dumb jokes and usually spent the first 10 minutes of each meeting chatting. When it came time to brainstorm, ‘‘we had lots of crazy ideas,’’ Rozovsky said.

One of her favorite competitions asked teams to come up with a new business to replace a student-run snack store on Yale’s campus. Rozovsky proposed a nap room and selling earplugs and eyeshades to make money. Someone else suggested filling the space with old video games. There were ideas about clothing swaps. Most of the proposals were impractical, but ‘‘we all felt like we could say anything to each other,’’ Rozovsky told me. ‘‘No one worried that the rest of the team was judging them.’’ Eventually, the team settled on a plan for a microgym with a handful of exercise classes and a few weight machines. They won the competition. (The microgym — with two stationary bicycles and three treadmills — still exists.)

Rozovsky’s study group dissolved in her second semester (it was up to the students whether they wanted to continue). Her case team, however, stuck together for the two years she was at Yale.

It always struck Rozovsky as odd that her experiences with the two groups were dissimilar. Each was composed of people who were bright and outgoing. When she talked one on one with members of her study group, the exchanges were friendly and warm. It was only when they gathered as a team that things became fraught. By contrast, her case-competition team was always fun and easygoing. In some ways, the team’s members got along better as a group than as individual friends.

‘‘I couldn’t figure out why things had turned out so different,’’ Rozovsky told me. ‘‘It didn’t seem like it had to happen that way.’’

O ur data-saturated age enables us to examine our work habits and office quirks with a scrutiny that our cubicle-bound forebears could only dream of. Today, on corporate campuses and within university laboratories, psychologists, sociologists and statisticians are devoting themselves to studying everything from team composition to email patterns in order to figure out how to make employees into faster, better and more productive versions of themselves. ‘‘We’re living through a golden age of understanding personal productivity,’’ says Marshall Van Alstyne, a professor at Boston University who studies how people share information. ‘‘All of a sudden, we can pick apart the small choices that all of us make, decisions most of us don’t even notice, and figure out why some people are so much more effective than everyone else.’’

Yet many of today’s most valuable firms have come to realize that analyzing and improving individual workers — a practice known as ‘‘employee performance optimization’’ — isn’t enough. As commerce becomes increasingly global and complex, the bulk of modern work is more and more team-based. One study, published in The Harvard Business Review last month, found that ‘‘the time spent by managers and employees in collaborative activities has ballooned by 50 percent or more’’ over the last two decades and that, at many companies, more than three-quarters of an employee’s day is spent communicating with colleagues.

In Silicon Valley, software engineers are encouraged to work together, in part because studies show that groups tend to innovate faster, see mistakes more quickly and find better solutions to problems. Studies also show that people working in teams tend to achieve better results and report higher job satisfaction. In a 2015 study, executives said that profitability increases when workers are persuaded to collaborate more. Within companies and conglomerates, as well as in government agencies and schools, teams are now the fundamental unit of organization. If a company wants to outstrip its competitors, it needs to influence not only how people work but also how they work together.

Five years ago, Google — one of the most public proselytizers of how studying workers can transform productivity — became focused on building the perfect team. In the last decade, the tech giant has spent untold millions of dollars measuring nearly every aspect of its employees’ lives. Google’s People Operations department has scrutinized everything from how frequently particular people eat together (the most productive employees tend to build larger networks by rotating dining companions) to which traits the best managers share (unsurprisingly, good communication and avoiding micromanaging is critical; more shocking, this was news to many Google managers).

The company’s top executives long believed that building the best teams meant combining the best people. They embraced other bits of conventional wisdom as well, like ‘‘It’s better to put introverts together,’’ said Abeer Dubey, a manager in Google’s People Analytics division, or ‘‘Teams are more effective when everyone is friends away from work.’’ But, Dubey went on, ‘‘it turned out no one had really studied which of those were true.’’

In 2012, the company embarked on an initiative — code-named Project Aristotle — to study hundreds of Google’s teams and figure out why some stumbled while others soared. Dubey, a leader of the project, gathered some of the company’s best statisticians, organizational psychologists, sociologists and engineers. He also needed researchers. Rozovsky, by then, had decided that what she wanted to do with her life was study people’s habits and tendencies. After graduating from Yale, she was hired by Google and was soon assigned to Project Aristotle.

P roject Aristotle’s researchers began by reviewing a half-century of academic studies looking at how teams worked. Were the best teams made up of people with similar interests? Or did it matter more whether everyone was motivated by the same kinds of rewards? Based on those studies, the researchers scrutinized the composition of groups inside Google: How often did teammates socialize outside the office? Did they have the same hobbies? Were their educational backgrounds similar? Was it better for all teammates to be outgoing or for all of them to be shy? They drew diagrams showing which teams had overlapping memberships and which groups had exceeded their departments’ goals. They studied how long teams stuck together and if gender balance seemed to have an impact on a team’s success.

No matter how researchers arranged the data, though, it was almost impossible to find patterns — or any evidence that the composition of a team made any difference. ‘‘We looked at 180 teams from all over the company,’’ Dubey said. ‘‘We had lots of data, but there was nothing showing that a mix of specific personality types or skills or backgrounds made any difference. The ‘who’ part of the equation didn’t seem to matter.’’

Some groups that were ranked among Google’s most effective teams, for instance, were composed of friends who socialized outside work. Others were made up of people who were basically strangers away from the conference room. Some groups sought strong managers. Others preferred a less hierarchical structure. Most confounding of all, two teams might have nearly identical makeups, with overlapping memberships, but radically different levels of effectiveness. ‘‘At Google, we’re good at finding patterns,’’ Dubey said. ‘‘There weren’t strong patterns here.’’

As they struggled to figure out what made a team successful, Rozovsky and her colleagues kept coming across research by psychologists and sociologists that focused on what are known as ‘‘group norms.’’ Norms are the traditions, behavioral standards and unwritten rules that govern how we function when we gather: One team may come to a consensus that avoiding disagreement is more valuable than debate; another team might develop a culture that encourages vigorous arguments and spurns groupthink. Norms can be unspoken or openly acknowledged, but their influence is often profound. Team members may behave in certain ways as individuals — they may chafe against authority or prefer working independently — but when they gather, the group’s norms typically override individual proclivities and encourage deference to the team.

Project Aristotle’s researchers began searching through the data they had collected, looking for norms. They looked for instances when team members described a particular behavior as an ‘‘unwritten rule’’ or when they explained certain things as part of the ‘‘team’s culture.’’ Some groups said that teammates interrupted one another constantly and that team leaders reinforced that behavior by interrupting others themselves. On other teams, leaders enforced conversational order, and when someone cut off a teammate, group members would politely ask everyone to wait his or her turn. Some teams celebrated birthdays and began each meeting with informal chitchat about weekend plans. Other groups got right to business and discouraged gossip. There were teams that contained outsize personalities who hewed to their group’s sedate norms, and others in which introverts came out of their shells as soon as meetings began.

After looking at over a hundred groups for more than a year, Project Aristotle researchers concluded that understanding and influencing group norms were the keys to improving Google’s teams. But Rozovsky, now a lead researcher, needed to figure out which norms mattered most. Google’s research had identified dozens of behaviors that seemed important, except that sometimes the norms of one effective team contrasted sharply with those of another equally successful group. Was it better to let everyone speak as much as they wanted, or should strong leaders end meandering debates? Was it more effective for people to openly disagree with one another, or should conflicts be played down? The data didn’t offer clear verdicts. In fact, the data sometimes pointed in opposite directions. The only thing worse than not finding a pattern is finding too many of them. Which norms, Rozovsky and her colleagues wondered, were the ones that successful teams shared?

I magine you have been invited to join one of two groups.

Team A is composed of people who are all exceptionally smart and successful. When you watch a video of this group working, you see professionals who wait until a topic arises in which they are expert, and then they speak at length, explaining what the group ought to do. When someone makes a side comment, the speaker stops, reminds everyone of the agenda and pushes the meeting back on track. This team is efficient. There is no idle chitchat or long debates. The meeting ends as scheduled and disbands so everyone can get back to their desks.

Team B is different. It’s evenly divided between successful executives and middle managers with few professional accomplishments. Teammates jump in and out of discussions. People interject and complete one another’s thoughts. When a team member abruptly changes the topic, the rest of the group follows him off the agenda. At the end of the meeting, the meeting doesn’t actually end: Everyone sits around to gossip and talk about their lives.

Which group would you rather join?

In 2008, a group of psychologists from Carnegie Mellon, M.I.T. and Union College began to try to answer a question very much like this one. ‘‘Over the past century, psychologists made considerable progress in defining and systematically measuring intelligence in individuals,’’ the researchers wrote in the journal Science in 2010. ‘‘We have used the statistical approach they developed for individual intelligence to systematically measure the intelligence of groups.’’ Put differently, the researchers wanted to know if there is a collective I. Q. that emerges within a team that is distinct from the smarts of any single member.

To accomplish this, the researchers recruited 699 people, divided them into small groups and gave each a series of assignments that required different kinds of cooperation. One assignment, for instance, asked participants to brainstorm possible uses for a brick. Some teams came up with dozens of clever uses; others kept describing the same ideas in different words. Another had the groups plan a shopping trip and gave each teammate a different list of groceries. The only way to maximize the group’s score was for each person to sacrifice an item they really wanted for something the team needed. Some groups easily divvied up the buying; others couldn’t fill their shopping carts because no one was willing to compromise.

What interested the researchers most, however, was that teams that did well on one assignment usually did well on all the others. Conversely, teams that failed at one thing seemed to fail at everything. The researchers eventually concluded that what distinguished the ‘‘good’’ teams from the dysfunctional groups was how teammates treated one another. The right norms, in other words, could raise a group’s collective intelligence, whereas the wrong norms could hobble a team, even if, individually, all the members were exceptionally bright.

But what was confusing was that not all the good teams appeared to behave in the same ways. ‘‘Some teams had a bunch of smart people who figured out how to break up work evenly,’’ said Anita Woolley, the study’s lead author. ‘‘Other groups had pretty average members, but they came up with ways to take advantage of everyone’s relative strengths. Some groups had one strong leader. Others were more fluid, and everyone took a leadership role.’’

As the researchers studied the groups, however, they noticed two behaviors that all the good teams generally shared. First, on the good teams, members spoke in roughly the same proportion, a phenomenon the researchers referred to as ‘‘equality in distribution of conversational turn-taking.’’ On some teams, everyone spoke during each task; on others, leadership shifted among teammates from assignment to assignment. But in each case, by the end of the day, everyone had spoken roughly the same amount. ‘‘As long as everyone got a chance to talk, the team did well,’’ Woolley said. ‘‘But if only one person or a small group spoke all the time, the collective intelligence declined.’’

Second, the good teams all had high ‘‘average social sensitivity’’ — a fancy way of saying they were skilled at intuiting how others felt based on their tone of voice, their expressions and other nonverbal cues. One of the easiest ways to gauge social sensitivity is to show someone photos of people’s eyes and ask him or her to describe what the people are thinking or feeling — an exam known as the Reading the Mind in the Eyes test. People on the more successful teams in Woolley’s experiment scored above average on the Reading the Mind in the Eyes test. They seemed to know when someone was feeling upset or left out. People on the ineffective teams, in contrast, scored below average. They seemed, as a group, to have less sensitivity toward their colleagues.

In other words, if you are given a choice between the serious-minded Team A or the free-flowing Team B, you should probably opt for Team B. Team A may be filled with smart people, all optimized for peak individual efficiency. But the group’s norms discourage equal speaking; there are few exchanges of the kind of personal information that lets teammates pick up on what people are feeling or leaving unsaid. There’s a good chance the members of Team A will continue to act like individuals once they come together, and there’s little to suggest that, as a group, they will become more collectively intelligent.

In contrast, on Team B, people may speak over one another, go on tangents and socialize instead of remaining focused on the agenda. The team may seem inefficient to a casual observer. But all the team members speak as much as they need to. They are sensitive to one another’s moods and share personal stories and emotions. While Team B might not contain as many individual stars, the sum will be greater than its parts.

Within psychology, researchers sometimes colloquially refer to traits like ‘‘conversational turn-taking’’ and ‘‘average social sensitivity’’ as aspects of what’s known as psychological safety — a group culture that the Harvard Business School professor Amy Edmondson defines as a ‘‘shared belief held by members of a team that the team is safe for interpersonal risk-taking.’’ Psychological safety is ‘‘a sense of confidence that the team will not embarrass, reject or punish someone for speaking up,’’ Edmondson wrote in a study published in 1999. ‘‘It describes a team climate characterized by interpersonal trust and mutual respect in which people are comfortable being themselves.’’

When Rozovsky and her Google colleagues encountered the concept of psychological safety in academic papers, it was as if everything suddenly fell into place. One engineer, for instance, had told researchers that his team leader was ‘‘direct and straightforward, which creates a safe space for you to take risks.’’ That team, researchers estimated, was among Google’s accomplished groups. By contrast, another engineer had told the researchers that his ‘‘team leader has poor emotional control.’’ He added: ‘‘He panics over small issues and keeps trying to grab control. I would hate to be driving with him being in the passenger seat, because he would keep trying to grab the steering wheel and crash the car.’’ That team, researchers presumed, did not perform well.

Most of all, employees had talked about how various teams felt. ‘‘And that made a lot of sense to me, maybe because of my experiences at Yale,’’ Rozovsky said. ‘‘I’d been on some teams that left me feeling totally exhausted and others where I got so much energy from the group.’’ Rozovsky’s study group at Yale was draining because the norms — the fights over leadership, the tendency to critique — put her on guard. Whereas the norms of her case-competition team — enthusiasm for one another’s ideas, joking around and having fun — allowed everyone to feel relaxed and energized.

For Project Aristotle, research on psychological safety pointed to particular norms that are vital to success. There were other behaviors that seemed important as well — like making sure teams had clear goals and creating a culture of dependability. But Google’s data indicated that psychological safety, more than anything else, was critical to making a team work.

‘‘We had to get people to establish psychologically safe environments,’’ Rozovsky told me. But it wasn’t clear how to do that. ‘‘People here are really busy,’’ she said. ‘‘We needed clear guidelines.’’

However, establishing psychological safety is, by its very nature, somewhat messy and difficult to implement. You can tell people to take turns during a conversation and to listen to one another more. You can instruct employees to be sensitive to how their colleagues feel and to notice when someone seems upset. But the kinds of people who work at Google are often the ones who became software engineers because they wanted to avoid talking about feelings in the first place.

Rozovsky and her colleagues had figured out which norms were most critical. Now they had to find a way to make communication and empathy — the building blocks of forging real connections — into an algorithm they could easily scale.

I n late 2014, Rozovsky and her fellow Project Aristotle number-crunchers began sharing their findings with select groups of Google’s 51,000 employees. By then, they had been collecting surveys, conducting interviews and analyzing statistics for almost three years. They hadn’t yet figured out how to make psychological safety easy, but they hoped that publicizing their research within Google would prompt employees to come up with some ideas of their own.

After Rozovsky gave one presentation, a trim, athletic man named Matt Sakaguchi approached the Project Aristotle researchers. Sakaguchi had an unusual background for a Google employee. Twenty years earlier, he was a member of a SWAT team in Walnut Creek, Calif., but left to become an electronics salesman and eventually landed at Google as a midlevel manager, where he has overseen teams of engineers who respond when the company’s websites or servers go down.

‘‘I might be the luckiest individual on earth,’’ Sakaguchi told me. ‘‘I’m not really an engineer. I didn’t study computers in college. Everyone who works for me is much smarter than I am.’’ But he is talented at managing technical workers, and as a result, Sakaguchi has thrived at Google. He and his wife, a teacher, have a home in San Francisco and a weekend house in the Sonoma Valley wine country. ‘‘Most days, I feel like I’ve won the lottery,’’ he said.

Sakaguchi was particularly interested in Project Aristotle because the team he previously oversaw at Google hadn’t jelled particularly well. ‘‘There was one senior engineer who would just talk and talk, and everyone was scared to disagree with him,’’ Sakaguchi said. ‘‘The hardest part was that everyone liked this guy outside the group setting, but whenever they got together as a team, something happened that made the culture go wrong.’’

Sakaguchi had recently become the manager of a new team, and he wanted to make sure things went better this time. So he asked researchers at Project Aristotle if they could help. They provided him with a survey to gauge the group’s norms.

When Sakaguchi asked his new team to participate, he was greeted with skepticism. ‘‘It seemed like a total waste of time,’’ said Sean Laurent, an engineer. ‘‘But Matt was our new boss, and he was really into this questionnaire, and so we said, Sure, we’ll do it, whatever.’’

The team completed the survey, and a few weeks later, Sakaguchi received the results. He was surprised by what they revealed. He thought of the team as a strong unit. But the results indicated there were weaknesses: When asked to rate whether the role of the team was clearly understood and whether their work had impact, members of the team gave middling to poor scores. These responses troubled Sakaguchi, because he hadn’t picked up on this discontent. He wanted everyone to feel fulfilled by their work. He asked the team to gather, off site, to discuss the survey’s results. He began by asking everyone to share something personal about themselves. He went first.

‘‘I think one of the things most people don’t know about me,’’ he told the group, ‘‘is that I have Stage 4 cancer.’’ In 2001, he said, a doctor discovered a tumor in his kidney. By the time the cancer was detected, it had spread to his spine. For nearly half a decade, it had grown slowly as he underwent treatment while working at Google. Recently, however, doctors had found a new, worrisome spot on a scan of his liver. That was far more serious, he explained.

No one knew what to say. The team had been working with Sakaguchi for 10 months. They all liked him, just as they all liked one another. No one suspected that he was dealing with anything like this.

‘‘To have Matt stand there and tell us that he’s sick and he’s not going to get better and, you know, what that means,’’ Laurent said. ‘‘It was a really hard, really special moment.’’

After Sakaguchi spoke, another teammate stood and described some health issues of her own. Then another discussed a difficult breakup. Eventually, the team shifted its focus to the survey. They found it easier to speak honestly about the things that had been bothering them, their small frictions and everyday annoyances. They agreed to adopt some new norms: From now on, Sakaguchi would make an extra effort to let the team members know how their work fit into Google’s larger mission; they agreed to try harder to notice when someone on the team was feeling excluded or down.

There was nothing in the survey that instructed Sakaguchi to share his illness with the group. There was nothing in Project Aristotle’s research that said that getting people to open up about their struggles was critical to discussing a group’s norms. But to Sakaguchi, it made sense that psychological safety and emotional conversations were related. The behaviors that create psychological safety — conversational turn-taking and empathy — are part of the same unwritten rules we often turn to, as individuals, when we need to establish a bond. And those human bonds matter as much at work as anywhere else. In fact, they sometimes matter more.

‘‘I think, until the off-site, I had separated things in my head into work life and life life,’’ Laurent told me. ‘‘But the thing is, my work is my life. I spend the majority of my time working. Most of my friends I know through work. If I can’t be open and honest at work, then I’m not really living, am I?’’

What Project Aristotle has taught people within Google is that no one wants to put on a ‘‘work face’’ when they get to the office. No one wants to leave part of their personality and inner life at home. But to be fully present at work, to feel ‘‘psychologically safe,’’ we must know that we can be free enough, sometimes, to share the things that scare us without fear of recriminations. We must be able to talk about what is messy or sad, to have hard conversations with colleagues who are driving us crazy. We can’t be focused just on efficiency. Rather, when we start the morning by collaborating with a team of engineers and then send emails to our marketing colleagues and then jump on a conference call, we want to know that those people really hear us. We want to know that work is more than just labor.

Which isn’t to say that a team needs an ailing manager to come together. Any group can become Team B. Sakaguchi’s experiences underscore a core lesson of Google’s research into teamwork: By adopting the data-driven approach of Silicon Valley, Project Aristotle has encouraged emotional conversations and discussions of norms among people who might otherwise be uncomfortable talking about how they feel. ‘‘Googlers love data,’’ Sakaguchi told me. But it’s not only Google that loves numbers, or Silicon Valley that shies away from emotional conversations. Most workplaces do. ‘‘By putting things like empathy and sensitivity into charts and data reports, it makes them easier to talk about,’’ Sakaguchi told me. ‘‘It’s easier to talk about our feelings when we can point to a number.’’

Sakaguchi knows that the spread of his cancer means he may not have much time left. His wife has asked him why he doesn’t quit Google. At some point, he probably will. But right now, helping his team succeed ‘‘is the most meaningful work I’ve ever done,’’ he told me. He encourages the group to think about the way work and life mesh. Part of that, he says, is recognizing how fulfilling work can be. Project Aristotle ‘‘proves how much a great team matters,’’ he said. ‘‘Why would I walk away from that? Why wouldn’t I spend time with people who care about me?’’

T he technology industry is not just one of the fastest growing parts of our economy; it is also increasingly the world’s dominant commercial culture. And at the core of Silicon Valley are certain self-mythologies and dictums: Everything is different now, data reigns supreme, today’s winners deserve to triumph because they are cleareyed enough to discard yesterday’s conventional wisdoms and search out the disruptive and the new.

The paradox, of course, is that Google’s intense data collection and number crunching have led it to the same conclusions that good managers have always known. In the best teams, members listen to one another and show sensitivity to feelings and needs.

The fact that these insights aren’t wholly original doesn’t mean Google’s contributions aren’t valuable. In fact, in some ways, the ‘‘employee performance optimization’’ movement has given us a method for talking about our insecurities, fears and aspirations in more constructive ways. It also has given us the tools to quickly teach lessons that once took managers decades to absorb. Google, in other words, in its race to build the perfect team, has perhaps unintentionally demonstrated the usefulness of imperfection and done what Silicon Valley does best: figure out how to create psychological safety faster, better and in more productive ways.

‘‘Just having data that proves to people that these things are worth paying attention to sometimes is the most important step in getting them to actually pay attention,’’ Rozovsky told me. ‘‘Don’t underestimate the power of giving people a common platform and operating language.’’

Project Aristotle is a reminder that when companies try to optimize everything, it’s sometimes easy to forget that success is often built on experiences — like emotional interactions and complicated conversations and discussions of who we want to be and how our teammates make us feel — that can’t really be optimized. Rozovsky herself was reminded of this midway through her work with the Project Aristotle team. ‘‘We were in a meeting where I made a mistake,’’ Rozovsky told me. She sent out a note afterward explaining how she was going to remedy the problem. ‘‘I got an email back from a team member that said, ‘Ouch,’ ’’ she recalled. ‘‘It was like a punch to the gut. I was already upset about making this mistake, and this note totally played on my insecurities.’’

If this had happened earlier in Rozovsky’s life — if it had occurred while she was at Yale, for instance, in her study group — she probably wouldn’t have known how to deal with those feelings. The email wasn’t a big enough affront to justify a response. But all the same, it really bothered her. It was something she felt she needed to address.

And thanks to Project Aristotle, she now had a vocabulary for explaining to herself what she was feeling and why it was important. She had graphs and charts telling her that she shouldn’t just let it go. And so she typed a quick response: ‘‘Nothing like a good ‘Ouch!’ to destroy psych safety in the morning.’’ Her teammate replied: ‘‘Just testing your resilience.’’

How To Make a Website. Step-by-Step Guide

Plan out the sections of the website, the main idea, and the functions. For example, a client needs a website on architectural bureau. One of the undermining elements this website should feature is the bureau’s works and contacts.

However, it’s also important to spot out what differentiates the bureau from other competitors. The bureau may focus on handling complex tasks, and share some unique features that make it stand out from other services. This is why uploading attractive and illustrative pictures won’t be enough! There is a place for content; you can share detailed descriptions of all the data, the process involved, and justification of decisions.

You don’t need to showcase all the projects on the website; center your focus on the most important ones, explain why the brand or company is regarded as experts and what distinguishes their service from the competitors. At this point, you will need to use less animation, embellishment, and other special effects.

Explain the concept of the company, and share main points that will emotionally engage and inspire website visitors.

Say, you want to create a landing page for a school specialized in design. The main purpose of this page is to help both students and parents understand the concept of design and what is expected from a designer.

Problem: Students want to become designers. However, most of them are yet to understand the rudiments, the trends, and significant differences in designs.

Objective: To help students know more about web design specializations and understand which suits them best.

Idea: What if we highlight some of the major design trends like —interactive, graphic, and industrial. And host an interview with professionals in each field? Telling compelling stories is one of the best ways to attract an audience, share stories from personal work experience, and compliment it with attractive pictures. People will be interested to read it, they will see what kind of person each professional is, whether their lifestyle is inspiring or familiar.

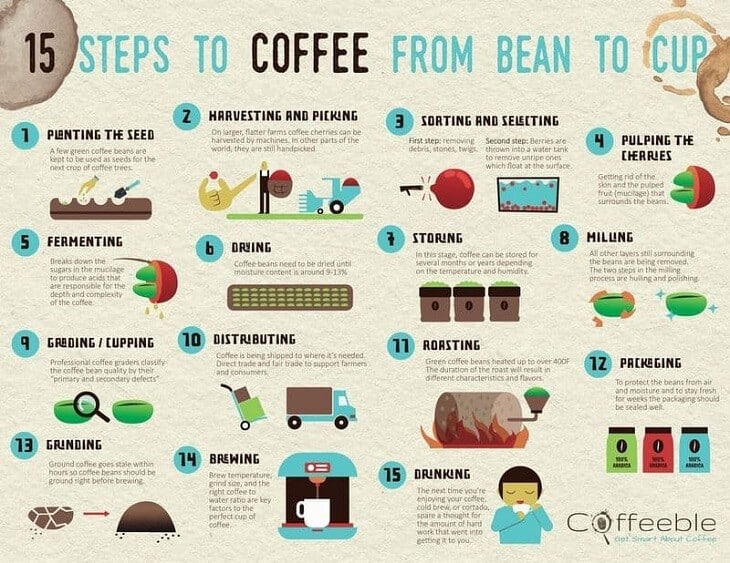

How Is Coffee Grown? 15 Steps To Coffee From Bean To Cup [With Infographic]

While sipping on my third coffee, grateful that the buzz I was getting was considered legal, I couldn’t help but think about how coffee is made and the curious sequence of events that lead to the perfecting of the beverage now in my hands.

The more you learn about the steps required to produce a good, healthy cup of coffee, the more you begin to wonder how it is that we even have coffee today.

The apocryphal story of the little Native American girl accidentally spilling corn kernels into the fire and discovering popcorn makes sense. It’s a simple one-step process.

But from tree to cup it takes a staggering 15 steps to get you that perfect cup of coffee!

Even the road to sobriety only has 12 steps. The next time you rush through your morning cup before dashing off to work, spare a thought for each of the people involved in these 15 steps that made it possible.

Infographic

15 Steps To Coffee

(Click to enlarge)

Embed this Infographic on Your Site: Copy and Paste the Code Below

#1 Planting The Seeds

Growing coffee isn’t as simple as throwing a few seeds on the ground and coming back a few years later.

Our journey from seed to cup actually doesn’t even start in the field where the coffee plants will eventually grow. Once harvested, some of the green coffee beans are kept to be used as seeds for the next crop of coffee trees.

These seeds spend their first year planted in nurseries (1) where they are carefully tended, watered and sheltered from the sun. Once they grow to between 18 and 24 inches, they’re tough enough to withstand the full sun and are removed from the nursery and planted in the field.

Left to their own devices these trees could grow as high as 20 feet but that would make harvesting a little tricky so they are generally pruned to around 8 to 10 feet. It takes between 3 to 5 years before the tree begins to produce coffee berries, also known as cherries because of their shape and red color.

Once ripe, these berries have a bright, deep red skin that covers a fleshy pulp and two little coffee beans in the center encased in a protective skin.

#2 Harvesting And Picking

Unlike a lot of other cash crops, coffee is normally grown on relatively small pieces of land by small-scale farmers.

When it comes to harvesting it’s a community affair with the whole family, friends and other farmers getting stuck in to help with the picking.

While there is a general time that the berries ripen, they tend to do it in stages which means that you can’t pick the whole lot at once.

This means that you’ve got to go out and pick the ripe berries, come back 8 to 10 days later to pick the next ones (2), and then come back another 8 to 10 days later to get the stragglers.

Selective And Strip Harvesting

In places like Brazil, where the coffee farms are larger and flatter, they are able to use machines that strip pick (3) the berries from the trees. This is a far less labor intensive process but it doesn’t discriminate between berries that are ripe or not.

The majority of coffee farms in other parts of the world are on landscapes that don’t allow for mechanical harvesting. This makes it a fairly labor intensive business and calls for good eyes and nimble fingers.

The advantage of picking by hand is that it allows for a more selective harvest. Being able to pick the berries only once they’re good and ready to go makes for better quality coffee. Unripe berries will have poorly developed beans and these will result in coffee with a bitter taste and sharp odor.

Well harvest coffee makes a huge difference to the final taste. Read more on the best coffee beans here.

Perfectly ripe berries will have well-formed beans with higher oil and lower acid content. This will give you the smooth, fragrant experience you want from your morning cup of sanity restorative. It’s tough work, though.

On average a good picker will pick around 100 to 200 pounds of coffee cherries a day and only 20% of that weight will eventually become coffee.

#3 Sorting And Selecting

Image credit: [haak78] / Depositphotos.com

What we’re really after are the two little beans at the center of the fruit.

To ensure that only the best beans pass onto the next step the coffee cherries are first sorted. There are a few ways to do this.

The simplest sorting that happens is by hand but winnowing the beans or using a large sieve to remove debris, stones, and twigs is also used.

To make absolutely sure that only ripe, good berries are used, the processor may also sort by water immersion. The cherries are thrown into a tank of water and the density difference between ripe and unripe cherries makes the unripe ones float to the top for easy extraction.

Now we’re left with only the best of the best and it’s time to free those beans from the pulp.

#4 Pulping The Cherries

The pulping process is all about getting rid of the skin and the pulped fruit (mucilage) that surrounds the beans.

Depulping is only done if the beans are destined for wet or semi-washed processing, but more on that later.

Within 24 hours of the cherries being picked, they are put through a depulping machine that removes the skin and most of the pulp. This pulp and skin is usually discarded to be used as compost but some “zero waste” coffee producers use these byproducts to make things like tea from the skins (4).

Tea from coffee you say?

We must be living in the future. After depulping, the beans still have some pulp attached and are ready for the fermentation process.

#5 Fermenting

The fermentation process is where the microbial reaction of bacteria and yeasts break down the sugars in the mucilage to produce acids.

It’s these acids that will be responsible for adding depth and complexity to the coffee. There are three main ways of processing the harvested cherries through the fermentation stage. Each process has its own logistical pros and cons and the process can have a significant effect on the taste of the final product.

Low Fermentation (Wet Processing)

This is the more modern, quicker process but it uses a lot of water. It has become the most common way of fermenting coffee.

The pulped beans are sorted by size and then thrown into fermentation tanks.

After 12 to 48 hours of fermentation in the tank, the naturally occurring enzymes dissolve the layer of mucilage surrounding the beans.

The beans are then washed thoroughly in fresh water to stop the fermentation process and to remove the last of the pulp.

This leaves the beans covered in just a thin sheath, or parchment, called the endocarp.

This process allows the farmer to carefully control how much fermentation takes place and results in a more consistent coffee with clean and complex flavors.

Medium Fermentation (Semi-washed)

For this method the cherries have their skins removed during the pulping process but instead of completely removing the mucilage, as in the wet process, the sticky flesh layer is left around the beans.

This allows for some measure of fermentation to continue throughout the drying process. This is also known as Honey or Pulped Natural coffee.

There’s actually no “washing” that takes place, semi or otherwise, so you’ll have to ask someone in a lab coat why they call it “semi-washed” because I don’t know.

The end result, though, is a coffee with a fruitier taste and more body than you get from the wet process.

High Fermentation (Dry process)

This is the oldest method and is still used in many coffee producing countries where water is scarce.

The ripe, freshly picked cherries do not go through the pulping process but are spread out, skin and all, on a large even surface to ferment while drying in the sun.

Because the skins are left on and the cherries aren’t all lying in the same tank each one ferments a little differently to the other.

This makes it a challenge to control the fermentation and get consistency from the coffee. When it’s done right, though, it delivers the most complex and intense flavors with great body.

#6 Drying

Regardless of the fermentation process used, the beans need to be dried until they reach a moisture content of around 11%. In the case of wet processing, the fermentation has already taken place and now it’s just a matter of drying the beans.

If the cherries went through the semi-wash or dry process then it’s at this point that the beans both dry out and ferment at the same time. The drying is either done mechanically or by laying them out on a large, flat space in the sun.

The cherries are raked regularly throughout the day to get them to dry evenly and to make sure that they don’t develop mold or bacteria. If it looks like it might rain the farmer has to run around frantically to cover the cherries.

It normally takes around 2 to 4 weeks until they dry to the point where they have an 11% to 12% moisture content.

With both the dry and semi-washed process, the beans are in contact with the pulp while drying and they absorb some of the taste characteristics of the fruit and this comes through in the coffee (5). It can be a risky process because if the cherries aren’t dried carefully and evenly they can be affected by fungi and bacteria which will give the coffee strong off-flavors.

A Unique Drying Process In Indonesia

In Indonesia, where they have high humidity, there is a higher risk of fungi developing during fermentation so they use a unique drying process to produce what is called “wet-hulled” coffee (6).

They pulp the cherries, dry them for a day, wash the mucilage layer off, dry them until they hit around 40%, ship them to market, dry them to around 25%, wet-hull the beans and then dry them some more until they get to 11%.

Wow! The next time you balk at the price of good Indonesian coffee just bear all of that in mind. Don’t feel too bad for them, though, they have year round summer and great beaches.

#7 Storage

Once properly dried you’re left with parchment coffee which is the beans with just the parchment surrounding them or what’s left of the bits of dried fruit and skin if they were dry processed.

In this form, the coffee can be stored for several months or even years depending on the temperature and humidity. There has been some demand for “aged” green coffees but for the most part, the beans are sent off for milling as soon as possible.

For the time that they are in storage they are put into sacks and stored on pallets in a way that allows for good airflow and that keeps them away from any moisture.

#8 Milling

Milling is the final stage in the process to get those little coffee beans out into the open with all the other layers removed.

The two steps in the milling process are hulling and polishing.

Hulling

The beans are thrown into a machine where they are milled to remove the parchment covering the beans as well as the skin and any leftover dried fruit in the case of dry processed coffee.

They’ve got to do this carefully so that they get all the little bits off without damaging the beans.

A machine removes the parchment covering as well as the skin and leftover dried fruit.

Polishing

If you’re extra fussy about having your beans shiny then the coffee goes through an optional stage of polishing where any of the silver skin left on the beans is removed. Don’t ask your barista if the beans he’s using were polished.

You’ll just sound pretentious and it doesn’t really make any difference to the taste. Once the hulling process is completed you’re left with beautiful little dried out light brown coffee beans.

Once again the coffee world keeps us wondering who’s actually in charge of nomenclature because they refer to these brown beans as “green coffee”.

An optional stage to make the coffee beans look more appealing is to polish them which removes the silver skin.

#9 Grading / Cupping

Before sending the whole batch off for roasting the coffee needs to be graded. Some fortunate people actually get paid to taste coffee and call it work.

After staring sagely at the beans for a while they make an initial judgment of the quality of the coffee based on the appearance of the beans. Then it’s on to the tasting, or cupping.

A sample of the beans will be roasted in a laboratory roaster, ground and then infused in boiling water. After letting it stand for a few minutes the cupper (taster) will then smell and taste the coffee.

He’ll tell you he’s not merely smelling it but “nosing” the coffee and that slurping he does while tasting is entirely necessary.

Regardless, the end result of this theatrics is that the coffee is graded as to its quality and suitability for blending with other coffees.

#10 Distributing

Once graded it’s a matter of planes, trains, and automobiles to get the coffee where it’s needed. Starting in bulk, the green beans will eventually be sold off in smaller batches to different coffee traders and distributors until it finally ends up at your local coffee roastery.

It’s not just about transport, though. The more links in the distribution chain, the further the consumer is removed from the producer. This can result in high margins for the middlemen and a lower price to the farmer.

It can also obscure the ethical standards that were adhered to in the production of the coffee. To combat this, organizations have been set up to promote direct trade and fair trade coffee.

Direct Trade

The idea behind direct trade is that the company that sells you the coffee sourced it directly from the producer. They make sure that the farmer gets a better than fair price rather instead of paying that premium to a bunch of middlemen.

Organizations promoting fair trade are more concerned with the economics of sustainable coffee production rather than ethical employment or ecological issues.

They say that they inspect the farms to check labor practices and use of pesticides but they don’t uniformly insist on a firm set of rules in these areas.

Fair Trade

The folks involved in Fair Trade coffee have a more holistic view of the production of coffee.

They look beyond just the farmer growing the coffee and have strict requirements regarding labor practices and ecologically friendly agricultural practices. The premise behind both of these organizations is good, but how effective they are as a force for good in coffee production is a contentious issue.

It’s good to remember, though, that how and where your coffee travels on its way to you is more than just a matter of logistics. The fewer links in the distribution chain between you and your coffee, the better chance there is of the guy producing it getting a fair price.

#11 Roasting

When the beans finally get nearer to where they will be consumed, it’s time to fire up the roaster.

This isn’t just a matter of flipping a switch and waiting for the timer to go off once it’s done. Roasting coffee is part science and part art. Inside those raw coffee beans is the potential to make a great cup of coffee.

The roasting process will either realize that potential or leave us wondering what might have….bean. *cough*

The trick is to take the acidity and flavors of each individual batch into account and then regulate the roasting temperature and duration to balance or enhance these. Typically this involves rotating them in a roaster that gets up to around 500 degrees Fahrenheit.

At about 400 degrees Fahrenheit the fragrant oil inside the beans (caffeol) begins to come out of the bean. This stage of the roasting process is called Pyrolysis and is what ultimately gives the coffee its flavor and aroma.

The duration of the roast will result in different characteristics and flavors from the lighter Medium and Full City roasts to the richer and darker Vienna and French Roasts.

Once the roasting process has been completed the beans are cooled by water or air to stop them developing further due to the heat trapped inside them.

#12 Packaging

Once the coffee is roasted the clock starts ticking.

You’ve got a limited time to grind those beans and get a delicious cup of coffee from them. It’s not only time that’s against you but air, moisture and UV rays all conspire to undo all the hard work that’s lead up to this point.

Because of this, the packaging that the roasted beans are stored in is more than just a marketing exercise. To protect the beans from air and moisture the packaging is sealed really well so that even if it’s on the shelf for a few weeks the beans will still be fresh once the seal is broken.

The Purpose Of A One-Way CO2 Valve

The packaging material is also opaque so that the beans are shielded from UV rays. Some coffee packaging will incorporate a one-way valve. Roasted beans will still de-gas for some time after they’ve been roasted so these one-way valves allow the carbon dioxide to escape the bag without allowing any oxygen in.

The problem with this is that as the carbon dioxide leaves the bag it takes volatile aromatics out along with it. Deciding to use these valves is a toss up (7) between the possibility of a bag of coffee exploding from the buildup of gasses and the need to retain as much of those aromatics as possible.

When you open that bag of beans next time imagine the arguments that went on in the coffee roasters boardroom to decide which way they were going to go.

#13 Grinding

When people speak of the “daily grind” it’s not usually a good thing. When it comes to coffee, though, the sound of those grinders preparing the beans for the final stages is music to our ears.

How finely the beans are ground depends on the method that will be used to brew the coffee.

If you’re going to be using a French Press or a vacuum coffee maker then the grind would be fairly coarse. For drip coffee makers you’d need a medium to medium / fine grind.

If you’re using a stove top espresso pot or an espresso machine then the grind would be fine to super fine.

If you’re grinding your own beans and you don’t need too fine a grind then a blade grinder will do the trick and doesn’t cost too much. You need to guesstimate how long to let it grind for until the coffee is as fine as you need it to be. A bit of trial and error and you’re sorted.

For more consistent and finer grinds the beans need to be ground in a burr grinder. The sound of the burr grinder is far easier on the ears if you’ve just woken up and the consistent grind allows for more efficient extraction when brewing.

Also, because the coarseness of the grind is dialed into the settings on the grinder there’s no need to push a button and count “One Mississippi, two Mississippi,…” like you need to with the blade grinder.

#14 Brewing

After grinding the beans it’s straight to the brewer with them. Whether the coffee is brewed in an espresso machine at your local coffee shop or the drip machine in your kitchen, this is make or break time.

It’s in this final stage where all the hard work that went before either culminates in a cup of amazing coffee or is undone by lousy pressure or wrong water temperature.

It’s here where the blood, sweat, and tears of the coffee farmer can be validated by a symphony of flavors, or be dashed by a barista distracted by that cute waitress in the short skirt.

At the end of the brewing stage, after already discarding the fruit of the cherry 10 thousand miles away, finally, the ground up remains of the beans are also thrown into the bin, leaving only the flavors that were once locked inside in the bottom of a dark cup.

#15 Drinking

After 14 steps and thousands of miles, what was once a little bean inside a berry near the equator (8) is now reduced to a collection of flavors and fragrances contained in a hot beverage that has made civilized life as we know it possible.

Or at least bearable.

The relief, satisfaction, and emotions that a rich and flavorful cup of coffee can result in transcends the olfactory senses and taste buds. As you drink it you’re sure that science has a perfectly bland explanation for what is happening to the synapses in your brain but it feels more like magic. More ethereal.

The next time you’re enjoying your espresso, cold brew, or cortado, spare a thought for the amount of work that went into getting it to you.

Think of the farmer’s aspirations as he tended his seedlings in the nursery.

Think of the worker who suddenly remembered that it was time to rush off to rake those beans drying in the sun.

Or the roaster wondering if he should risk let the beans roast just a little longer to get the taste he was after.

And as you consider the number of steps it took to get the coffee in your cup, as you savor the flavors and the mouthfeel, you may not think that 15 steps are that many after all.

You could be forgiven for wondering that it didn’t take a whole lot more.

If you liked this article and know someone who appreciates coffee as much as you do then please share it with them by clicking the buttons below.

Did you like our list of how coffee is made? Did we skip a step? If so, let us know in the comments section below.

Husband, father and former journalist, I’ve combined my love of writing with my love of coffee to create this site. I love high end products, but write all my content with budget conscious coffee enthusiasts in mind. I prefer light roasts, and my normal brew is some sort of pour over, although my guilty pleasure is the occasional flat white.