How to distinguish voices

How to distinguish voices

How to distinguish voice from snoring?

Background: I’m working on an iPhone application (alluded to in several other posts) that «listens to» snoring/breathing while one is asleep and determines if there are signs of sleep apnea (as a pre-screen for «sleep lab» testing). The application principally employs «spectral difference» to detect snores/breaths, and it works quite well (ca 0.85—0.90 correlation) when tested against sleep lab recordings (which are actually quite noisy).

Problem: Most «bedroom» noise (fans, etc) I can filter out through several techniques, and often reliably detect breathing at S/N levels where the human ear cannot detect it. The problem is voice noise. It’s not unusual to have a television or radio running in the background (or to simply have someone talking in the distance), and the rhythm of voice closely matches breathing/snoring. In fact, I ran a recording of the late author/storyteller Bill Holm through the app and it was essentially indistinguishable from snoring in rhythm, level variability, and several other measures. (Though I can say that apparently he didn’t have sleep apnea, at least not while awake.)

So this is a bit of a long shot (and probably a stretch of forum rules), but I’m looking for some ideas on how to distinguish voice. We don’t need to filter the snores out somehow (thought that would be nice), but rather we just need a way to reject as «too noisy» sound that is overly polluted with voice.

Files published: I’ve placed some files on dropbox.com:

The first is a rather random piece of rock (I guess) music, and the second is a recording of the late Bill Holm speaking. Both (which I use as my samples of «noise» be differentiated from snoring) have been mixed with noise to sort of obfuscate the signal. (This makes the task of identifying them significantly more difficult.) The third file is ten minutes of a recording of yours truly where the first third is mostly breathing, middle third is mixed breathing/snoring, and the final third is fairly steady snoring. (You get a cough for a bonus.)

All three files have been renamed from «.wav» to «_wav.dat», since many browsers make it maddeningly difficult to download wav files. Just rename them back to «.wav» after downloading.

Update: I thought entropy was «doing the trick» for me, but it turned out to mostly be peculiarities of the test cases I was using, plus an algorithm that wasn’t too well designed. In the general case entropy is doing very little for me.

I subsequently tried a technique where I compute the FFT (using several different window function) of the overall signal magnitude (I tried power, spectral flux, and several other measures) sampled about 8 times a second (taking the stats from the main FFT cycle which is every 1024/8000 seconds). With 1024 samples this covers a time range of about two minutes. I was hoping that I would be able to see patterns in this due to the slow rhythm of snoring/breathing vs voice/music (and that it might also be a better way to address the «variability» issue), but while there are hints of a pattern here and there, there’s nothing I can really latch onto.

(Further info: For some cases the FFT of signal magnitude produces a very distinct pattern with a strong peak at about 0.2Hz and stairstep harmonics. But the pattern is not nearly so distinct most of the time, and voice and music can generate less distinct versions of a similar pattern. There might be some way to calculate a correlation value for a figure of merit, but it seems that would require curve fitting to about a 4th order polynomial, and doing that once a second in a phone seems impractical.)

I also attempted to do the same FFT of average amplitude for the 5 individual «bands» I’ve divided the spectrum into. The bands are 4000-2000, 2000-1000, 1000-500, and 500-0. The pattern for the first 4 bands was generally similar to the overall pattern (though there was no real «stand-out» band, and often vanishingly small signal in the higher frequency bands), but the 500-0 band generally was just random.

Bounty: I’m going to give Nathan the bounty, even though he’s not offered anything new, given that his was the most productive suggestion to date. I still have a few points I’d be willing to award to someone else, though, if they came through with some good ideas.

What The FACH? What Is Your Vocal Type?

The Vocal Fach System was developed in Germany at the end of the 19th Century for opera houses to create distinct categories for all the roles in an opera in order to aid auditions and casting.

Fach means classification, specialty, category. Singers were placed in a Fach according to their voice types and they would only study the characters that belonged in that category. ( laugh sometimes because I think of it like the Indian “Caste” system. Meaning, once you were born into poverty, no matter how many times you come back in reincarnation, you will always be a pauper. Or if you were born into royalty, you would always come back a king. Nonetheless, it is still a very helpful way to understand “voice types.” With that said: Opera houses would keep records of singers according to Fach and they would call them in for auditions according to which roles were available.

All together singers and roles were placed in a Fach according to the following vocalcharacteristics:

The Fach System is still used widely throughout the world (especially in Europe), and although it might seem as a very stringent way of classifying singers, knowing your specific voice type can help you make better decisions when auditioning.

Most composers have particular voice types in mind, some times even specific singers, when working on their operas. Nowadays, directors and conductors try to recreate the feeling of particular characters by choosing singers whose voice power, size, timber, color, and range match the composer’s intentions.

Think about it: would a soprano with a heavy and powerful voice be a good fit for the role of a young girl like Gilda in Rigoletto? And how about a bright and airy tenor for the role of a dramatic character like Canio in Pagliacci?

I wish this book was translated into English. This book by Rudolf Kloiber’s Handbuch der Oper, is the definitive complete manual on voice types, auditioning, and roles. Since it hasn’t been published in English, below please find a very scaled down version of vocal fachs, their categories, their characteristics and their ranges (which I will include as well).

This is a collective table of the main 25 voice types in the Fach system.

The 25 Voice Types

| Type | English | German | Characteristics |

| Soprano Voice Types | Soubrette | Spielsopran | Young, light, bright |

| Lyric Coloratura Soprano | Lyrischer Koloratursopran | High, bright, flexible | |

| Dramatic Coloratura Soprano | Dramatischer Koloratursopran | High, dark, flexible | |

| Lyric Soprano | Lyrischer Sopran | Warm, legatto, full | |

| Character Soprano | Charaktersopran | Bright, metallic, theatrical | |

| Spinto /Young Dramatic Soprano | Jugendlich-dramatischer Sopran | Powerful, young, full | |

| Dramatic Soprano | Dramatischer Sopran | Powerful, dark, rich | |

| Mezzo-Soprano Voice Types | Coloratura Mezzo-Soprano | Coloratura Mezzo-Soprano | Agile, rich, bright |

| Lyric Mezzo-Soprano | Lyrischer Mezzosopran | Strong, flexible, lachrymose | |

| Dramatic Mezzo-Soprano | Dramatischer Mezzosopran | Rich, powerful, imposing | |

| Contralto Voice Types | Dramatic Alto | Dramatischer Alt | Powerful, full, metallic |

| Low Contralto | Tiefer Alt | Low, full, warm | |

| Tenor Voice Types | Countertenor | Contratenor | High, agile, powerful |

| Lyric Tenor | Lyrischer Tenor | Soft, warm, flexible | |

| Acting Tenor | Spieltenor | Flexible, theatrical, light | |

| Dramatic Tenor | Heldentenor | Full, low, stamina | |

| Character Tenor | Charaktertenor | Bright, powerful, theatrical | |

| Baritone Voice Types | Lyric Baritone | Lyrischer Bariton | Smooth, flexible, sweet |

| Cavalier Baritone | Kavalierbariton | Brilliant, warm, agile | |

| Character Baritone | Charakterbariton | Flexible, powerful, theatrical | |

| Dramatic Baritone | Heldenbariton | Powerful, full, imposing | |

| Bass Voice Types | Character Bass | Charakterbass | Full, rich, stamina |

| Acting Bass | Spielbass | Flexible, agile, rich | |

| Heavy Acting Bass | Schwerer Spielbass | Full, rich, imposing | |

| Serious Bass | Seriöser Bass | Mature, rich, powerful |

Major Category – Voice Types by Range and Tessitura

If you sing in a choir or take voice lessons, you have probably already been classified as a soprano, mezzo-soprano, or contralto (alto) if you are a woman, and a countertenor, tenor, baritone, or bass if you are a male. But are you really sure you’ve been classified correctly? Test your voice according to the following scales.

Soprano

Voice Type: Soprano, Range: B3 – G6

Soprano is the highest female voice type. There are many types of sopranos like the coloratura soprano, lyric soprano, the soubrette etc. which differ in vocal agility, vocal weight, timbre, and voice quality; I will talk about them in our livestream. All of the sopranos have in common the ability to sing higher notes with ease.

A typical soprano can vocalize B3 to C6, though a soprano coloratura can sing a lot higher than that reaching F6, G6 etc.

Mezzo-Soprano

Voice Type: Mezzo-Soprano, Range: G3 – A5

Mezzo-Soprano is the second highest female voice type. In a choir, a mezzo-soprano will usually sing along the sopranos and not the altos and will be given the title of Soprano II. When the sopranos split in half, she will sing the lower melody as her timbre is darker and tessitura lower than the sopranos.

Though in opera mezzo-sopranos most often hold supporting roles and trouser roles, i.e. male roles, there are notable exceptions like those of Carmen and Rosina in The Barber of Seville, where the prima donna is a mezzo-soprano. A typical mezzo-soprano can vocalize from G3 to A5, though some can sing as high as typical soprano.

Contralto

Voice Type: Contralto, Range: E3 – F5

Contralto is the lowest female voice type. In a choir, contralto’s are commonly know as altos and sing the supporting melody to the sopranos. This doesn’t mean that contraltos are not as important. On the contrary, because true altos are hard to find, a true alto has greater chances of a solo carrier than a soprano.

A contralto is expected to be able to vocalize from E3 to F5, however, the lower her tessitura, the more valuable she is.

Countertenor

Voice Type: Countertenor, Range: G3 – C6

Countertenor is the rarest of all voice types. A countertenor is a male singer who can sing as high as a soprano or mezzo-soprano utilizing natural head resonance. As I said before, countertenors are extremely hard to come along and their ability to sing as high as C6 is admired by religious music connoisseurs.

Though extremely unique, countertenor is not an operatic voice type, as historically, it was the castrati (male singers castrated before puberty) who would be chosen for the female operatic roles – it was not proper for women to sing in the opera. Instead, countertenors were popular in religious choirs, where women were also not allowed to participate.

The castratti are out of the scope of this post, but for those who are interested to learn more about them, I would like to recommend the movie Farinelli, a literary twist on the life of Farinelli, the most famous castrato of all times.

Tenor

Voice Type: Tenor, Range: C3 – B4

Tenor is the highest male voice type you will find in a typical choir. Though it is the voice type with the smallest range, it barely covers 2 octaves from C3 to B4, tenors are the most sought after choir singers for two major reasons. The first reason is that there aren’t as many men singing in choirs to begin with. The second reason is that most men, singers or not, fall under the baritone voice type.

In the opera, the primo uomo is most often a tenor, and you will know he is a tenor because of the ringing quality in his voice. A true tenor has a high tessitura, above the middle C4, and uses a blend of head resonance and falsetto, as opposed to falsetto alone.

Many a baritone will try to use this technique to classify as tenor and some will be successful; you’ll know who they are because of their red faces when trying to sing the high notes in the tenor melodic line. 🙂

Baritone

Voice Type: Baritone, Range: G2 – G4

Baritone is the most common male voice type. Though common, baritone is not at all ordinary. On the contrary, the weight and power of his voice, give the baritone a very masculine feel, something that in the opera has been used in roles of generals and, most notably, noblemen. Don Giovanni, Figaro, Rigoletto, and Nabucco are all baritones.

In a choir, a baritone will never learn about the particulars of his voice, since he will have to sing either with the tenors or the basses. Most baritones with a high tessitura choose to sing with the tenors, and respectively, the ones with a lower tessitura sing with the basses. Their range is anywhere between a G2 and a G4 but can extend in either way.

If you sing tenor and can’t reach the higher notes with ease, or sing bass and can’t reach the lower notes naturally, you’re most probably a baritone and you shouldn’t worry about it, we’ll discuss this in the live stream.

Voice Type: Bass, Range: D2 – E4

Bass is the lowest male voice type, and thus a bass sings the lowest notes humanly possible. I tend to think of the deep bass notes as comparable to those of a violoncello, though some charismatic basses can hit notes lower than those of a cello. A bass will be asked to sing anywhere between a D2 and an E4. A cello’s lowest note is a C2.

Just with every extreme, it’s really hard to find true basses and it’s almost impossible in the younger ages where the male bodies are still developing.

Though in a choir basses might have rather monotone melodic lines, in the opera they have a great range of roles to choose from. Basses are used as the villains and other dark characters, the funny buffos and in comic-relief roles, the dramatic princes, the noble fathers of heroines, elderly priests and more.

Now that you have learnt all about the major categories in voice types, I’m sure you’ll want to know how to distinguish between the secondary categories. Do you know the difference between a lyric soprano and a dramatic soprano or a leggero tenor and a spinto tenor? How can you tell which one you are? We will be discussing this in our Youtube Live Stream!

See you soon!

Watch this 30 second before and after video of a student who took the course for only one year:

Want To Learn to Sing Better?

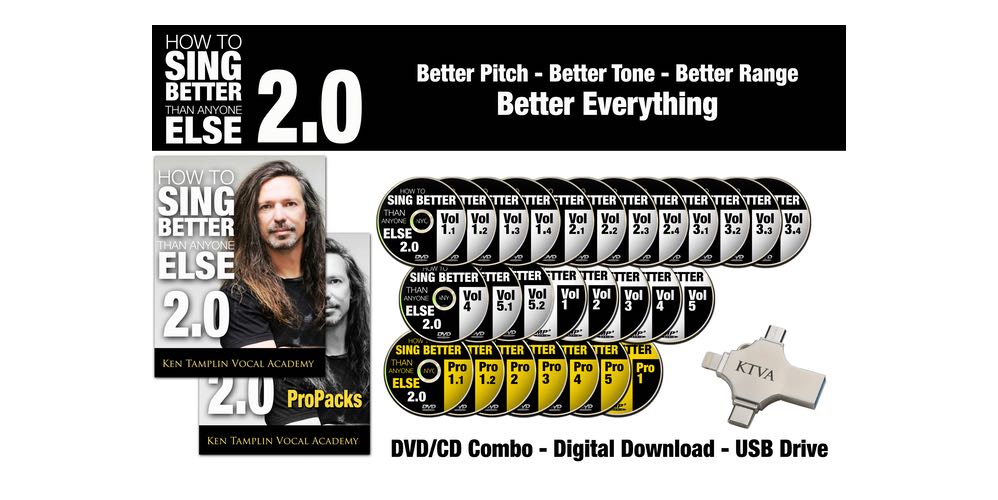

Well, you CAN! Get started today with our ‘world famous for good reasons’ How To Sing Better Than Anyone Else PRO BUNDLE vocal course and you will be well on your way to singing better than you ever thought possible!

Active KTVA Students in The KTVA Singers Forum:

““It’s awesome. The private sections of the forum are worth the price of admission alone. I struggled with 2 different tertiary (university Level) level teachers (6 months each about 8 years ago) telling me my voice just wouldn’t be able to do what i wanted to be able to do and even if it could, the material i wanted to be able to sing would be too ‘Dangerous.’ Absolute rubbish. If you do the work thats laid out in this course, you are golden, I started in March Last year struggling to hit the E4 note in ‘Under the Bridge’ chorus now I can sing this stuff:

Honestly man, you are not going to find a bad review here. The course and this forum completely demystifies every single aspect of great singing. Just be prepared to do the work.”

Streeter – KTVA Singers Forum

Gary Schutt

Anthony Vincent

Tori Matthieu

Sara Loera

Gabriela Gunčíková

Xiomara Crystal

Voice classification using Deep Learning, with Python

Here’s how to use Deep Learning to classify the voices of an audio track

Sometimes humans are able to do certain kind of stuff very easily, but they are not able to properly describe how they do it. For example, we are able to clearly distinguish two different voices when they speak, but it is hard to describe the exact features that we use to distinguish them. As the task is hard to describe, it is even harder to teach a computer how to do it. Fortunately, we have data, and we can use the examples to train our machines.

Let’s get started!

1. The Setup

As the title say, I’ve used Python. In particular, I’ve used these libraries:

We will use them during the process.

2. The Dataset

I’ve used the first 30 minutes of the first US 2020 presidential debate. In particular, the task is to distinguish three voices:

So we basically have a 20 frequencies representation of the signal. The sample rate is 22010 Hz, thus the time vector can be extracted using this code:

As we have the time in fraction of seconds, we convert the ending minute in seconds:

Now we have it done.

Nonetheless, it is about the whole speech, while, as it has been said, the audio is shorter. For this reason, a portion of the dataset has been taken too.

Let’ s give a look:

It is now comfortable to convert the audio data into a pandas dataframe:

Here we go. So now we have 20 columns X 74200+ rows… pretty huge. For this reason a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) reduction has been performed:

Now, let’s give a look.

As it was predictable, it is necessary to look at the time series to get a sense of what is going on. As we want to keep it simple, let’s use the Mutual Information to select the most informative feature and have a time series out of it.

The most informative is the 2 component.

Understanding The Different Types Of Singing Voices

For some people, singing comes naturally. Others need to put in time and training to figure out how to properly use their voice. Whatever camp you’re in, it’s essential to understand the different types of singing voices so that you can make the most out of your vocal range.

Below, we’ll detail everything you need to know about the different singing voice types, demystify vocal vocabulary, and share some vocal technique tips so that you can improve your singing voice for the better. Let’s jump into it!

Determining Your Vocal Quality

We are all able to notice certain things about our voices. For example, you may observe that you have a deeper voice type than your friend, or perform better when belting versus singing softly. However, there’s a lot more to both male voice and female singing voice types. Professional vocalists evaluate their singing voice based on a number of factors including:

While these terms are helpful to understand, it’s often best to find a professional vocal teacher to help you properly categorize your own voice. It can be difficult for us to have an unbiased view of our own vocal ranges, so having an outside source can be one of the most useful tools for your current and future vocal development.

Understanding Different Singing Voice Types

Each of the qualities listed above helps us to put our voices within a certain singing voice type. Understanding singing voice types can make it easier for you to find a part in a choir that suits you or craft music around your particular voice type.

Bass Voice

The bass sings as the lowest voice type out there and is performed by male voices since they naturally have a lower vocal range. A bass voice range’s tessitura is usually around notes E2 to E4 (using middle c as the frame of reference), giving them a vocal range of about two octaves.

Real bass singers are somewhat rare and difficult to come across, as even male voice types tend to have voices fall in a slightly higher singing range. Some of the most famous bass voices include Barry White and Bing Crosby. You’ll find that singers that meet this voice classification are sometimes referred to as bass-baritone singers since their upper range has a similar vocal range to the baritone voice type. This low voice is often used to convey nobility or wisdom.

Baritone Voice

The baritone voice singer’s voice type is higher than baritone but has a lower range than the tenor. A typical baritone range rests with a tessitura from A2 to A4, though the dramatic baritone may be able to share some of the lower notes found in a baritone and bass vocal range. In opera, this vocal type often represents a comedic, heroic, or dramatic role. Some modern baritone singers that may come to mind include Hoizer or John Legend.

Tenor Voice

Tenors are a more common vocal range for male voices, with a lighter vocal weight than baritone and bass singers. This male voice type has a comfortable range around C3 and C5, surrounding middle c. A tenor sounds higher in speaking and singing than the baritone and bass, and their voices can be seen all throughout popular music today. The tenor male voice is typically the highest male voice in an opera setting, it is often used for the hero or romantic interest. They are often responsible for carrying the melody as the male voice in music. You might recognize tenor voices in popular music from male voices like Sam Smith and Steve Wonder.

Countertenor Voice

The countertenor voice is the highest male voice, sharing vocal range with female voices. These singers are rare with their most comfortable voice range around E3 to E5. You may mistake these particular tenor voices for female voices. It’s possible for young boys to start with a countertenor voice range and then transition to tenor or baritone over time. It can be difficult to find a true classical countertenor voice, though today, those with a strong falsetto may produce a similar vocal quality as seen with pop singers like Bruno Mars or Alfred Deller.

Contralto Voice

The contralto voice is the lowest female voice type. The sweet spot for this singer’s voice type is usually between E3 to E5 which notably shares a similar range as countertenor voice. You’ll find that the contralto voice has a heavier vocal weight and sits as a middle-range voice type, usually supporting higher voices. It has a darker timber than other female voice types giving it plenty of power. Some examples include Cher and Tracy Chapman. Contralto voices may find it easier to belt than higher, soprano voices.

Alto Voice

This is the second lowest of female singing voice types, still providing plenty of depth and vocal weight with Messituras of F3 to F5. Some altos can expand their range into their higher register with training, sharing some of the same notes as sopranos. While the term «alto» is now used as a more general term to categorize a lower female singing voice, you can find plenty of examples of songs performed within an alto vocal range including «Rehab» by Amy Winehouse.

Mezzo Soprano Voice

A mezzo soprano voice can be equated to the female voice type of the male baritone. This midrange voice is lower than the typical soprano voice and often shares range with the vocal registers of altos and sopranos. They tend to have lighter vocal weight and tone than altos with a tessitura around A3 to A5. In the opera, this voice category is often used to portray boys or young men, even though soprano mezzo is carried out by female voices. These warm voices are popularized by artists like Lady Gaga and Christina Aguilera.

Soprano Voice

The high vocal range rests with soprano signers. A typical soprano voice lies with a tessitura around middle C to C6. This voice type is known for creating bright, dreamy, crystal vocal expressions with expert attuned pitch. Sopranos usually carry the melody of a song, supported by backing voices of altos and other vocal types. In operas, the soprano is usually cast as the heroine, portraying innocence and youth. Modern examples of soprano singers include Ariana Grande and Whitney Houston.

Coloratura Soprano

This is the highest singing voice of all choral music vocal types, sharing the vocal qualities of a soprano voice, but with thick vocal cords to perform impressive opera runs and thrills. Coloratura sopranos are rare though you can find a couple of contemporary music vocalists who might fall into this vocal category. Mariah Carey might be the most likely to earn this coloratura soprano distinction, as exemplified by her ability to sing high notes and runs effortlessly throughout her pop music career.

How Does Singing Work?

So, what exactly happens when we sing? Taking the time to understand the science behind your voice can make it easier for you to understand how you can improve your vocal range over time.

All singing can be traced back to the power of breath. Since singing is produced by the vibration of airflow past our vocal cords, if there’s no breath, there’s simply no sound! When we breathe in to sing, we take in air from our diaphragm and control the air as we exhale, producing a vocal tone.

Our essential vocal components are housed in the larynx and are referred to as the vocal folds. The vocal folds are made up of individual ligaments that vibrate to create sound. It’s worth noting that these vocal folds can deteriorate over time which is why so many famous singers have to undergo surgery or other treatments to deal with their vocal trauma.

Like an athlete, trained vocalists are able to gain control over the muscles in the larynx, effectively producing better pitch and tone quality over time.

However, some people are simply built with stronger singing voices. The mouth, throat, and nasal cavity’s anatomy also play a part in vocal tone and structure since they serve as a passageway for the air vibrating your vocal folds.

Thankfully, many people can improve their vocal range and vocal quality with practice and training. A lot of «good» singing breaks down to the ability to emulate the true tone quality of notes, and with training, this process will undoubtedly become easier.

Breaking Down The Vocal Registers

There are several vocal registers that singers fluctuate between depending on a piece of music. Here are some of the most common vocal registers and what you might expect from each of the sections of your voice.

Vocal Fry

Vocal fry is the lowest vocal register that shortens vocal folds without a lot of airflow, causing the listener to hear the vocal folds intersect with one another. This isn’t a traditional vocal register, but it’s used sometimes in more contemporary music, so it’s worth mentioning. Vocal fry can also be known as the pulse register or glottal scrape.

Chest or Modal

Chest or modal voice is your comfortable singing voice and range that allows you to produce tones without having to add air or falsetto to supplement or support your voice. The chest voice’s timbre is typically darker and warmer than the higher vocal registers, carrying a bit more vocal weight.

Mixed or Middle Voice

This is the in-between of your chest voice and head voice. You may start to hear some breathier tones intertwined with your chest voice. It’s darker than your head voice, but a bit brighter than your modal voice.

This is the high end of your vocal range, characterized by higher pitches and elongated vocal folds. It is your higher, brighter voice that can be carried downwards in pitch, though oftentimes it makes sense to opt for chest voice if you’re within a deeper range.

Falsetto

When vocal cords are long, thin, and motionless, singing above a vocalist’s usual or modal range. While this isn’t necessarily a vocal register (depending on who you talk to) it certainly has a specific tonal quality worth acknowledging.

Whistle

These tones are extremely bright where the vocal cords are closed, with only a tiny portion vibrating, creating a shrill, high-pitched sound. Typically, whistle tones are performed by only a select female voice type with an impressive higher tone.

Oftentimes, professional vocal coaches will focus singers on creating a smooth blend throughout the vocal registers. It can also help to be able to identify which part of the vocal register you’re in so that you can adjust your signing approach for as much vocal support as possible.

Musical Glossary

As you grow in your journey as a singer, you’re sure to come across some of these terms. Here are some of the most important vocabulary terms you’ll want to know as it relates to you as a singer.

Accelerando

This is the gradual speeding of the tempo in a choir or ensemble.

Allegro

Allegro is a musical quality, presenting as fast and lively.

Alliteration

Repetition introduced at the beginning of adjacent words helps make a song or phrase more memorable.

Andante

Adante means moderately slow time.

An aria is a song in an opera intended for a single voice.

A division of music coming at the end of a measure in sheet music.

BPM stands for beats per minute and is one of the ways tempo is measured, particularly in Western music.

Bel Canto

An operatic style known for displaying vocal technique. This phrase translates to, «beautiful singing».

Chord

A group of harmonious notes, usually consisting of at least 3 independent tones.

Chorus

A group of multiple singers, usually consisting of multiple vocal parts.

Coloratura

A singer who specializes in particularly athletic music full of thrills and runs.

Composer

The creator or writer of music.

Concerto

A composition designed for one or more solo instruments.

Conductor

A leader of the orchestra, otherwise known as maestro.

Crescendo

To become progressively louder.

Decrescendo

To become progressively quieter.

A composition intended for two performers.

Dynamics

Variations in volume throughout a piece of music.

Ensemble

Music written for a group of musicians.

A half step lower than the natural version of a note.

Forte

This translates to «loud».

Fortissimo

This is a dynamic marking for «very loud».

Harmony

When two or more independent tones are played at the same time, typically with a sonically pleasing interval like a major third or perfect fourth.

The family of notes in which a piece of music resides. Distinguished in the key signature at the beginning of a piece of music.

Largo

Referring to a slow style.

Lyrics

Sung words of a musical composition.

Natural

The natural form of a note, as opposed to a sharp or flat.

Octave

A note that’s twice as high or low in pitch as another. A higher or lower tone using the same note.

A composition that is numbered as a series in a composer’s works.

Pianissimo

Translates to «very quiet» in relation to a song’s dynamics.

Pitch

The highness or lowness of any particular tone.

Presto

Presto means «very fast» in regards to pacing direction.

Rallentando

Ritard

Ritard or ritardando equates to the gradual slowing of tempo in a piece of music.

Staccato

Each note is performed separately, short and independent of one another.

Trill

Alternating pitch in between two notes.

Tutti

Translates to «all», as to ask all voice types on a composition to sing together.

Vibrato

The vibration that naturally occurs with some singing voices.

How To Determine Your Vocal Range

One of the best ways to narrow down the voice types in order to find your own is to take the time to determine your vocal range. Thankfully, you can do so with a couple of minutes of your time and a little bit of singing:

Since vocal range is the distance between your lowest and highest note, you simply have to determine where these points are. To do this, go to a piano and start at middle C or C4. From there, play notes progressively down, singing their pitch one at a time. Once you can’t go any further, you reached the lower end of your range. Mark that note and return to middle C.

Next, repeat the process, but this time moving up in pitch from middle C until you can’t sing the high notes of the higher keys. This is the upper limit of your range. Now that you have your lower and higher notes, you should have your vocal range!

If you don’t have a piano handy, you can use a video tool like this one as a pitch reference:

If you can’t tell if you’re hitting the pitch or the notes, be sure to enlist in a trusted friend for help. Remember that great vocals take a lot of work to pull off— Don’t be embarrassed if you’re not Whitney Houston from the start!

Remember that your vocal range can vary based on a variety of factors, so on any given day, your vocal range may be different. However, your home base or ideal vocal sweet spot will remain largely the same. With practice and training, you should be able to expand your initial vocal range over time.

How To Expand Your Vocal Range

Thankfully, with proper training and practice, your vocal range can grow and expand over time. Here are some ways you can help build your vocal range over time.

1. Practice good posture. Something as simple as proper posture can surprisingly have a great effect on your overall vocal quality and tone. Stand up straight, with your feet planted a shoulder-width apart. Keep your shoulders back and try to keep your head straight while singing.

2. Work with a vocal coach. Since so much of our voice type and natural singing ability is highly personalized, it only makes sense to take an individualized approach to build up our voices. If you’re serious about training your voice for the better, consider investing in trained vocal instruction, or at the very least, joining a community choir.

3 . Breathe from the diaphragm. While singing, you should see your diaphragm expand and contract, not your shoulders take in air, and put it out. Focus on taking in air properly. Even committing to something as simple as breathing exercises can help improve your vocal control and tone over time.

4. Practice! If you’re not singing, you’re not familiarizing yourself with your voice for the better. While there is something to be said about vocal rest, it’s wise to sing along to references so that you can start to get an idea of where your weak points are. Focus on matching your pitch with your reference tracks and take the time to warm up before reaching for those higher notes.

5. Relax your jaw. As we reach for high notes, our vocal cords stretch to produce a higher tone. Therefore, relaxing your jaw can provide your singing voice with the room it needs to hit those higher pitches properly. Allow your soft palette to drop and let your mouth elongate, but keep your head steady. You shouldn’t need to move your head down or up in order to reach a strong pitch.

6 . Take care of your voice. A lot can show up on the microphone. Since you are your own instrument, in order to expand your vocal range, you need to take care of yourself physically throughout your singing career. This means taking the time to warm up before singing, using vocal exercises, practicing, but also things like getting enough sleep, staying hydrated, and being patient. If you have a big vocal performance on the horizon, it can also be wise to avoid carbonated drinks and dairy products that may cause mucus build-up.

Regardless of your voice type, learning to sing properly can take time. Anyone can sing, but only trained vocalists understand how to make the most out of their singing voice type. Be sure to pay your vocals the same attention as you would with any other instrument. With a little bit of consistent practice and training that’s suitable for your singing voice type, you’ll improve your vocal quality in no time at all. Above all, enjoy learning and practicing the art of singing!

How to Determine Singing Range and Vocal Fach (Voice Type)

Many singers who e-mail me have questions about how they should go about classifying their voices. They are curious to know whether they are altos or sopranos, baritones or tenors, and they want to know what they should expect of their voices after gathering more information about them.

This article presents a basic guide to (self) vocal classification. More information about the common voice types and about voice classification can be found in Understanding Vocal Range, Vocal Registers and Voice Type.

A few words of caution: It is never wise to make a quick classification of any given singing voice. (Sometimes singers are in a hurry to label voices because they want to understand their voices better or because they are anxious to begin singing suitable repertoire.) The development of good vocal habits are essential to correct classification, and if a singer is lacking in certain critical technical abilities, it may be easy to incorrectly categorize that voice. Singers should take the time to gain solid technical skills within a limited and comfortable range of pitches before attempting to push the voice to its extremes (either high or low). Once the basics of good technique have become established in this comfortable area, the true quality of the voice will emerge, and the upper and lower limits of the range can then be explored safely.

Furthermore, it is imperative that voice classification not be made until the voice has reached a certain level of maturation. Chronological age should not be used as an indicator of maturity, as each voice matures at its own rate. Although an eighteen-year-old male singer may have experienced voice change at fourteen, it’s as though his voice is really only four-years-old. Young voices should never be encouraged to sound more mature by falsely darkening their tone. The imitation of mature voices heard on recordings or in live performances is potentially damaging. Likewise, more mature voices should never attempt to sound more youthful than they naturally would.

It is vital that vocal teachers avoid encouraging the development of a voice exclusively to their own tastes, as every individual instrument has its own unique qualities and abilities, and all voices should, therefore, be encouraged to develop into what they are naturally designed to sound like. A singer should never be forced or encouraged to train as a certain voice type if that voice type is not what the instrument is naturally. Although all voices within the same voice type (or vocal Fach) have common characteristics, each sub-type has unique features that require a particular approach in teaching.

Also, even if a particular singer in a choir is capable of singing a different voice part (e.g., an alto who is able to comfortably sing the highest notes necessary for a given soprano part), he or she should not be encouraged to regularly sing that other voice part. (This often happens when a choir is short on the number of voices to sing a certain voice part, and the choir director makes a plea for the singer to switch parts.)

I strongly suggest that you hire a vocal technique instructor who can help you make sense of the information that you discover and collect about your voice, and who will ensure that your technique is not limiting your voice in any way nor causing your voice to be incorrectly classified.

WHY CLASSIFY THE VOICE?

Classifying singers is most common and necessary for opera singers, as their voice types determine which roles they will be cast for and will perform. Attempting to perform demanding operatic roles that do not suit one’s voice type, (i.e., they are not written for nor intended to be sung by singers of another voice type), can be damaging to the vocal instrument. Singers often attempt unsuitable repertoire and choose to sing in an overly high or low tessitura because they may feel pressure to impress audiences with their range or because, especially in the operatic world, they believe certain voice types (i.e., tenors and sopranos) to be more desirable than others.

Because most singers of contemporary genres aren’t classically trained and don’t apply classical technique to their singing nor produce characteristically ‘classical’ sounds, it’s often a little more difficult to classify these singers by traditional means, (e.g., by using the German Fach system). However, singers of contemporary genres do also risk injury to their voices if they habitually sing in a pitch area that is not compatible with their voice’s natural tendencies or if they frequently use a quality of voice that is unnatural to their individual voice. Although voice classification may not be as critical to the vocal health and success of the rock, pop or jazz singer, as I will explain in the next paragraph, knowing some details about one’s voice can help that singer to make better overall choices. While it may not be all that useful for singers of contemporary styles to know whether they have ‘lyric’ or ‘dramatic’ voices, or even whether they are ‘baritones’ or ‘mezzo-sopranos’, understanding a little bit about why their voices shine in certain areas of their range or in certain parts of a song can help them to select or write songs that will highlight their strengths and minimize evidence of their weaknesses.

If you sing contemporary genres, voice classification is likely to be less crucial to your career. (Mistakes can nevertheless be harmful, so you should still be true to your voice’s natural qualities and features.) While, in opera, all factors of the voice must be considered in order to determine whether or not a singer fits perfectly into a certain (already written and publicly performed numerous times) role, there is a great deal more flexibility and leeway within contemporary music. Not only is much of the sung music original and written for the individual singer, but the characteristics of the lead singer’s voice (e.g., range, tessitura, technical abilities and style) are also instinctively factored into the writing of original songs. Transposition is an option whenever a singer performs a contemporary cover song, whereas operatic songs are almost always performed in their original keys, making accurate voice classification and appropriate casting all the more critical for the classical singer. Furthermore, a certain degree of ‘rawness’ and uniqueness of sound is often expected from singers of contemporary styles of music, so one particular voice type isn’t necessarily going to be more desirable than the others.

HOW ARE VOICES CLASSIFIED?

Voices are classified by their perceived qualities or characteristics, including range, tessitura, weight, and color (timbre), as well as vocal registration and vocal transition points that include ‘breaks’ in the voice. (I explain each of these characteristics in the sections below.)

In both classical and choral music, voices are most commonly classified as basses, baritones, tenors, altos, mezzo-sopranos and sopranos. (For more descriptions of each of these voice types, refer to Understanding Vocal Range, Vocal Registers and Voice Type, or review the last section of this article, Putting the Pieces Together: Making A Determination Of Voice Type.) There are also intermediate voice types, which may have a range or tessitura lying somewhere between two voice types or parts (e.g., a bass-baritone), or may have a vocal weight that lies somewhere between light and heavy (e.g., a dramatic coloratura soprano, etc.).

A note of interest: Most individuals possess medium voices. In other words, the majority of male singers are baritones, and the majority of female singers are mezzo-sopranos. True bass voices are a rarity, and true soprano voices are not quite as common as one might think. (The fact that most leading operatic roles are written for and sung by sopranos may give people the wrong idea about how prevalent that particular voice type truly is.) Possessing a voice that is simply ‘somewhere in the middle’ may not seem all that glamourous and exciting, but it is a fact of nature. How those of us with medium voices develop and use our instruments is what will determine whether or not our voices will stand out from the rest of the crowd.

Voice type is largely determined by the physical size and structure of the larynx and the rest of the vocal tract. As a general rule, those singers with larger vocal tract dimensions have lower passaggio pitch areas and lower ranges and tessituras, while those with smaller vocal tract dimensions have higher passaggio pitch areas, ranges and tessituras. Physical size (e.g., build or height) of the individual doesn’t always provide a clear indication of whether or not that person has a higher or lower, nor lighter or heavier, instrument. It’s what’s inside that counts.

SCIENTIFIC PITCH NOTATION

First, to avoid any confusion, I’d like to briefly discuss scientific pitch notation, as I will be using it as I make reference to range and to the locations of the registration pivotal points (passaggi) for each voice type.

The benefit of using scientific pitch notation is that it establishes consistency across the board, eliminating ambiguity and making discussion of specific pitches more accurate and lacking in confusion. (Please read the note below regarding the nonstandard labeling of electronic keyboards, which can introduce some confusion when discussing a voice’s range.) For example, a ‘high C’ can have different meanings depending on whose voice is singing that note. A soprano’s high C, considered to be the defining note for a soprano voice type, would be located two octaves above middle C (labeled C6), whereas a tenor’s high C, based on the highest note that is generally required in standard tenor repertoire, would refer to C5. Using only the letter name for a given note can also create some confusion when discussing range.

Keep in mind that many electronic keyboards have the notes labeled differently. In many cases, the octave numbering is shifted either up or down, (though most commonly down), by as much as two numbers. This is because many electronic keyboards have ranges that are smaller than the full concert-sized piano (with eighty-eight keys). Typically, the manufacturer bases the labeling of the keys on how many octaves the individual keyboard has, not on the frequencies of the individual notes, (which means that this labeling system is not based on true scientific pitch notation at all). An electronic keyboard with only six octaves, for example, would designate the first octave on that particular device ‘octave 1’, which would leave the middle C on that particular instrument labeled as ‘C3’ instead of C4, even though its frequency, and thus pitch, matches that of C4. This misleading labeling practice creates a great deal of confusion and inaccuracy in discussing pitch and range for singers who aren’t aware of it. Therefore, counting the notes on a short keyboard will not be an appropriate or accurate way of working out the scientific pitch names of notes. For all intents and purposes, the C that is located in the middle of the keyboard should be considered C4, regardless of how it has been labeled by the manufacturer.

RANGE

In its broadest sense, range refers to the full number of octaves or partial octaves, that a singer is able to sing. The bottommost part of the range is marked by the specific lowest pitch that a singer is able to vocally produce. The uppermost part of the range is marked by the specific highest pitch that a singer is able to produce. The interval between these two notes denotes the singer’s range. A range beginning at C3 and ending at G5, for example, means that the singer is able to sing two-and-a-half octaves.

Typically, untrained singers have a much more limited range than they would have if they were trained. Oftentimes, it is the upper range that is lacking, or is shortened considerably by this lack of training because they don’t apply correct technique to the upper-middle and head registers. (Many untrained singers are unable to access their head registers, and therefore have a significantly shortened range, even though their instruments might be physically capable of singing a much broader range with some training in correct vocal technique.) As a result of focusing exclusively on capable range, many singers incorrectly classify their own voices, assuming that because they can’t sing high notes, they must be of a lower vocal Fach (voice type).

Furthermore, some voices are innately capable of singing a greater range of notes than others. There are some singers who have exceptional ranges and are capable of singing several octaves, including areas of pitch most commonly reached by other voice types. There are true altos, for example, who have such well-developed and extensive head registers that considering their upper ranges alone would suggest that they are possibly mezzo-sopranos or even sopranos (e.g., a certain alto might be able to sing higher than a certain soprano, but that doesn’t make her a soprano.) Likewise, there are higher voiced singers, such as tenors, who are physically capable of singing lower than some baritones can.

In classical singing, poorly produced upper and lower notes would not actually be considered part of the singers range. In contemporary singing, ‘performable’ range is defined differently because singers generally make use of microphones that can amplify lower and quieter notes, whereas in opera, a singer is expected to sing over orchestral accompaniment without the aid of amplification, and these quieter notes that don’t carry (aren’t loud enough) or have a timbre that is inconsistent with the rest of their range don’t count.

Then, beginning at a comfortable upper-middle note, begin singing a chromatic scale upwards in pitch. Write down the highest note that you are able to sing, even if it doesn’t sound wonderful.

Now, calculate the distance in octaves and partial octaves between these lowermost and uppermost two notes. The interval (distance or range of pitches) between these two notes serves as your vocal range or vocable compass, by definition in contemporary styles or genres of singing. The highest and lowest notes may not be considered part of your ‘performable’ range (singable compass), as they may not be well produced or have a pleasant tone and sufficient carrying power, but they will do for starters.

If you feel as though your range is smaller than average, or smaller than you would like it to be, consider signing up for lessons with a skilled voice instructor who will help you learn better vocal technique and extend your range. In the meantime, you may read some tips that I have written on increasing vocal range in Tips For Practicing Singing: A Practical Guide To Vocal Development.

TESSITURA

Essentially, tessitura of the voice refers to the area of the singer’s range where he or she is most comfortable singing. This area is generally where the voice is the most pleasant sounding and is its strongest and most dynamic. Consistency of timbre, as well as the ‘strength’ behind the notes, also help to define tessitura. If you take a close look at the vocal range figures in Understanding Vocal Range, Vocal Registers and Voice Type, you will probably get an indication of the tessitura that is most likely for each voice type.

A soprano is likely to be most comfortable and have the most pleasant tone in her upper middle and upper range, whereas a mezzo-soprano would be strongest in the middle of her range and an alto’s voice would stand out best in her lower to middle range. Bass singers will have a more limited higher end, both in range and in dynamic ability, than tenors, who will likely be more limited, both in range and in dynamic ability, in the lower end.

Bear in mind that, with the exception of the occasional vocal embellishment and vocalises (wordless, vocalized ‘gymnastics’ used to give added drama to a song), singers of contemporary genres don’t typically sing in their head registers, as the modified vowels and acoustics of head voice tones don’t tend to suit most contemporary styles of singing. (To gain a clearer understanding of how head voice is correctly defined, and why many untrained singers and singers and teachers of contemporary methods and styles misunderstand it, read Vocal Registration and Contemporary Teaching Methods in my article on ‘Belting’ Technique.) This means that this higher area of their range (above their second passaggio) may be very underdeveloped through lack of use and practice, and therefore may not sound as strong as it possibly could be. This also means that even a natural soprano or tenor may not feel as comfortable as he or she otherwise would if he or she were to spend more time regularly training and exercising the voice in the upper end of the range.

Tessitura is another helpful piece of information to possess when attempting to choose a key signature for a given song. Taking into consideration where the bulk of the melody of a song is written, a singer can adjust the key, either moving it up or moving it down, to better match his or her own tessitura, and therefore offer a stronger performance throughout the entire song. This technique is particularly useful for matching areas of a song that the singer would like to make sound more dramatic and powerful, such as choruses or bridges, with the strongest part of the singer’s range.

WEIGHT

Vocal weight refers to the perceived ‘lightness’ or ‘heaviness’ of a voice. A lighter voice, often described in the opera world as ‘lyric‘, usually has a more youthful quality to it, whereas a heavier voice, often described as ‘dramatic‘, usually has a fuller and more mature quality.

In general, lighter voices find it easier to sing at higher pitches (higher lying tessituras), have more vocal agility, and change registers at slightly higher pitches than heavier voices within the same voice type do. The ease with which the lighter voice negotiates the extreme upper range is not necessarily due to better technical facility than that of the heavier voice, but to the fact that those pitches lie in less demanding relationship to the lighter voice’s passaggi events. (Read page two of this article for more information on the passaggi locations.)

There is a common misconception that the tenor and soprano voices are high, light instruments, quite distinct in character and timbre from that of the baritone and alto. In reality, though, such an incorrect assumption may lead to inaccurate voice classification, which may, in turn, cause frustration and voice health issues. A lyric baritone voice, for example, may have no greater difficulty singing and sustaining the same high notes as a dramatic tenor.

TIMBRE

Timbre simply refers to the quality or ‘colour’ of tone being produced by the singer.

I am purposely leaving timbre (vocal ‘colour’) out of this discussion because it is a very complex topic to broach. Though it is important in singing and in determining vocal Fach, it is also difficult to describe, and there are countless timbres amongst individual singers. Using passaggi locations, range, tessitura and weight should suffice in determining your voice type.

THE PASSAGGI

The passaggi are the two pivotal registration points or register transition points at which the human voice switches from one register into the adjacent register. The primo (first) passaggio lies between the chest register and the middle register in women or between the chest register and the zona di passaggio (‘passage zone’) in men. The secondo (second) passaggio is located between the middle register or zona di passaggio and the head register. (Note that falsetto is not a vocal register. Rather, it is a quality of voice that is produced in the male singer’s upper range.)

To locate your primo (lower) passaggio, where the voice switches from the chest register into the zona di passaggio (in men) or middle register (in women), sing an eight-note ascending scale beginning in comfortable lower range, below the average location for the first passaggio. For a male singer, begin around F3 (the F below middle C) or E3. For a female singer, begin around A3 or B3.

The first passaggio marks the end of the chest register and the beginning of the zona di passaggio (in men) or middle register (in women). At the first passaggio, you may notice a lightening of timbre or a physical sensation that the voice is becoming lighter or ‘lifting’ up out of the chest. This lightening may be more noticeable in heavier voices. You may also notice a register break, in which the voice abruptly shifts into the next (higher) register with a ‘clunk’, change of volume, a weakening of tone, etc..

For male singers who are into the habit of carrying their chest voice timbres up through their zona di passaggio, instead of encouraging head voice tones in this area, a lightening of the voice may not occur. Instead, they may notice a point at which their voices will usually begin to feel and sound more strained and ‘shouty’, and singing the next few notes higher becomes more difficult and increasingly less pleasant to the ears. Female singers who also habitually push their chest voice functions up higher in the scale than is recommended will also likely begin to notice some strain, tightness and ‘shoutiness’, or a diminished quality of timbre above the first passaggio. That point at which the voice first becomes more strident and tense may be the location of the first passaggio. (Again, for singers who regularly apply incorrect technique to their singing, locating the passaggi can be particularly challenging.)

To locate your secondo (upper) passaggio, where your voice switches from the middle register or zona di passagio into the head register, you’ll want to sing an eight-note scale beginning several notes below the place where most voices within your gender switch. For a man, begin around A3 or B3 and sing a full eight-note ascending scale. For a woman, begin singing an eight-note ascending scale around G4 or A4. Both of these starting points should place the voice several notes below the average passaggio pitch, and the scale should extend to a few notes above these (passaggio) pitches. Regardless of your voice type, starting at or around this point should work for you.

If you have good vocal stamina and range, you can choose to sing a two-octave scale to listen for both registration shifts within the same scale, instead. Because the distance between the first and second passaggi is much shorter in males than in females (an interval of roughly a fourth, as compared to an octave in females), male singers may be able to sing just one octave, if begun at the correct location, to locate both registration pivotal points. However, I find that it is often more helpful, especially for lighter voices and voices with poor technique, to break up the scale and focus on finding just one passaggio at a time. (This can be done most effectively by simply singing shorter, five-note scales in every key, ascending the keyboard, beginning in comfortable lower range.)

Note that not all passaggi are located on whole tones within the scale. They may occur on a sharp or a flat that doesn’t actually fall within the same scale or key (e.g., on ‘accidentals’). Additionally, the passaggi of the human voice are not necessarily related to pitches on a piano. Some voices may actually transition between registers on imprecise (e.g., slightly flat or sharp, yet not quite the semitone below or above) pitches. When I am assisting students in finding their passaggi, and also in improving their blending skills, I typically use shorter chromatic scales, playing all white and black keys in an ascending pattern. Playing all semitones ensures that the location of the register shift is identified more precisely.

If you are unable to sing more than just a few notes above the upper passaggio notes listed above, it is possible that you are not accessing your head voice at all. You will need to work on your technique, if this is the case. If you do not hear an acoustic shift that creates a brighter, ringing tone, or if you feel strain, tightening and tension as pitch ascends, you may not be singing in head voice, and may instead be carrying your middle voice function up past the point where you should be switching into head voice function. If you are not yet able to access your head register correctly, rely solely upon the location of your first passaggio to help you determine your voice type. (Consider hiring a vocal technique instructor to help you learn correct technique that will enable you to sing in your head register, thereby significantly increasing your singable range and protecting your voice from strain, fatigue or injury.)

Again, the region between these two passaggi in males is designated the zona di passaggio (passage zone). In females, this area is called the middle register. Because men speak almost entirely in chest voice, they tend to have a more extended chest register than women do. The first passaggio marks the end of speech-inflection range (the range of pitches used during normal speaking tasks) in men. Because women tend to speak with much greater inflection than men, raising the pitches of their voices more frequently and substantially during conversation, their speech-inflection range tends to be broader. In women, the end of speech-inflection range is marked by the second passaggio. These differences account for why the zona di passaggio in men is significantly shorter than the middle register in women, and why the chest register in men covers more range than it does in women.

In classical singing, the middle register in higher-voiced women is traditionally extended somewhat in most pedagogic approaches, and the area between the two passaggi is often called the ‘long middle range‘. Due to slight differences in the length of the chest register between lower and higher voice types, (and also the differences in the head registers between higher and lower voice types), higher voices are generally encouraged to change into mixed voice function (middle voice) lower in the scale, giving them a slightly longer middle register than their lower-voiced colleagues. Lyric sopranos are encouraged to never carry open chest tones up any higher than Eb4 or even D4, and dramatic sopranos do not generally sing in chest voice higher than F4. Mezzo-sopranos never carry chest voice function higher than F#4, and contraltos, with their naturally deeper, heavier voices, can safely delay entering the middle range up to G4 or even Ab4. In many schools of classical singing, female singers are taught to carry head voice tones down much lower in the scale than would be done in contemporary styles of singing, even when classical technique is otherwise applied.

PUTTING THE PIECES TOGETHER: MAKING A DETERMINATION OF VOICE TYPE

Below is a list of the passaggi locations and the voice types with which they are typically associated. Although the passaggi for every mature (adult) singer remain fairly stable and are consistent, those listed below may not be completely accurate for all singers within the same voice type. (These transition points are actually more predictable across male voice types, though, than across female voice types due to the greater amount of overlapping between female voice types.) The late master teacher and writer Richard Miller argued that no single, arbitrary pitch can be established which functions as a line of demarcation between registers. In other words, determining vocal Fach is not always clear-cut, as all voices are unique. There is a great deal of overlap, so the passaggi locations listed below should be taken as ‘approximate’ locations, and should not be used exclusively as the defining voice characteristic. Instead, register transition points should be reviewed and analyzed along with the other characteristics of the individual singing voice, including range, tessitura, weight and timbre. (As cautioned in the first section, it is wise to avoid drawing a conclusion overly quickly.)

The differences in the passaggi locations between individuals reflects differences in their physical structures. These differences are not necessarily discernable to the naked eye, as they are within the body (the larynx and vocal tract). Therefore, a person of smaller frame and stature may have a surprisingly low range or heavy, powerful voice, whereas another person of larger build and height may have a surprisingly high range or a light vocal weight. Additionally, due to the greater diversity of laryngeal size and vocal-tract construction among males, range demarcations among male voice categories are more distinct than those of female voices. The passaggio points of male voices can be plotted over a wider range of notes. In males, a number of specific pitch designations for the passaggi exist within each voice category (e.g., several possible notes for tenor voices, and quite a few for baritones and basses), whereas only a semitone or whole-tone difference exists within female categories.

Even though it is likely sufficient for a singer of contemporary genres to know his or her range, tessitura and primary Fach designation (i.e., bass, baritone, tenor, alto, mezzo-soprano or soprano), I have included information about each sub-type, as well, to help those who are considering singing choral or operatic music.

PASSAGGI LOCATIONS FOR MALE VOICES

G3 and C4These passaggi locations are generally associated with the low bass (basso profundo), who has a low-lying tessitura and range. This exceptionally rare voice type often sings in the vocal fry register. Choral parts designated ‘Bass’ do not reflect the range and tessitura of a true bass. Instead, these lines are more suitable for lower baritones, such as bass-baritones or dramatic baritones. (In the case of choral music, ‘Bass‘ denotes a voice part or designated vocal line rather than a voice type. Men who sing bass parts in choirs often mistakenly assume that they are indeed basses.)Ab3 and Db4These passaggi are generally associated with the lyric bass (basso cantante), a lighter bass voice, likely with more agility and an ability to handle more florid passages than a heavier bass voice.A3 and D4These pitches reflect the registration pivotal points of the bass-baritone, an intermediate voice type with a range and tessitura lying somewhere between that of the bass and that of the baritone. He may have an extensive lower range, but have more of the timbral qualities of the baritone. He may also exhibit the upper range of a baritone.Bb3 and Eb4These pitches reflect the registration transition locations for a dramatic baritone (baritono drammatico). The dramatic baritone is a heavier-weighted baritone voice that is richer and fuller, and sometimes harsher, than a lyric baritone and with a darker quality.B3 and E4These passaggi locations reflect those of the lyric baritone (baritone lirico). The lyric baritone is a lighter-weighted baritone voice that is often mistakenly classified as a dramatic tenor because of the lighter timbre and the vocal agility (dexterity) as compared to other baritones.C4 and F4These passaggi locations reflect those of either the baritone-tenor or the robust tenor (tenore robusto). These tenor voices are the heaviest and lowest of all tenor voices. Singers who change registers as these locations may eventually have to choose between training as either a baritone or a tenor.C#4 and F#4These notes reflect the passaggi locations for the dramatic tenor (tenore drammatico). The dramatic tenor is a tenor of substantial weight, with a rich, emotive, ringing, dark-toned, very powerful and dramatic voice.D4 and G4The spinto tenor (tenore spinto), also called a lyric-dramatic tenor, changes registers roughly at these pitches. This voice has the brightness and height of a lyric tenor, but a heavier vocal weight, enabling the voice to be ‘pushed’ to dramatic climaxes with less strain than the lighter-voiced tenors. Some spinto tenors may have a somewhat darker timbre than a lyric tenor, as well, without being as dark as a dramatic tenor.These passaggi locations may also reflect those of a lyric tenor (tenore lirico). The lyric tenor voice is warm and graceful, with a bright, full timbre that is strong enough to be heard over an orchestra but is not heavy.D#4 and G#4The light tenor (tenore leggiero) likely changes registers at these two notes. This voice is a light, lyric instrument, is very agile and is able to perform difficult and florid (fioritura) passages.E4 (or F4) and A4 (or A#4)The high tenor (tenorino) likely changes registers at these notes. This tenor has the highest upper range and tessitura of all tenors. His voice is very agile and he may have an extensive falsetto range or be capable of countertenoring.

PASSAGGI LOCATIONS FOR FEMALE VOICES

Remember that the classical long middle range or register for the lyric soprano would be from Eb4 (first passaggio) to F#5 (second passaggio); for the dramatic soprano from F4 to F#5; the mezzo-soprano from F#4 to F5; and for the contralto from G4 to E5 or Ab4 to D5. Many sopranos are more comfortable switching into cricothyroid dominant function (middle voice) lower in the scale, rather than remaining in chest voice. Women of lower voice types may have a higher primo passaggio because of the natural weightiness of their voices and the comfort that they have singing in chest voice and a lower secondo passaggio, and thus a shortened middle register when classical technique is applied to singing.

Also, though it is possible for women to be of intermediate voice types, because there isn’t as much of a possible range of pitches for the passaggi locations within each voice type as there is amongst men, (particularly tenors), it is not quite as easy to designate precise pitch locations for the registration events of intermediate female voice types. The contralto-mezzo, for example, might share passaggi locations with the mezzo-soprano, but her timbre, weight, tessitura and range might indicate that she is not quite as high-voiced as the mezzo-soprano.

As always, don’t classify your voice without first taking into consideration all the possible characteristics of the voice, including range, tessitura, weight, timbre and passaggi locations.

ACCEPTING YOUR VOICE CLASSIFICATION

There are many unique qualities to individual voices, and each voice type has its own strengths and its own appeal. Every singer needs to accept and fully embrace his or her unique vocal qualities, strengths and limitations if he or she is to make the most of the instrument with which he or she has been entrusted.

In the majority of cases, when an adult singer has had a change in vocal Fach, it is because he or she had been training and attempting to sing (with little success, a great deal of discouragement and likely some physical discomfort) repertoire written for a higher Fach. A lower Fach designation and training in an appropriate tessitura for the singer’s voice are sometimes thought of as embarrassing or less desirable, as though the singer’s voice will somehow be perceived as less worthy for being of a lower voice type. However, the voice may be saved and the singer’s career prolonged and made more successful by making such a necessary and healthy change. Remember that just because you are able to sing in a higher or lower range, that doesn’t necessarily make it a good or healthy one for you to be singing in regularly.

Once a singer learns and accepts what voice type he or she belongs to, the only other question remaining is what kind of tenor, alto, etc. he or she is. If a singer has a natural lightness in his or her vocal weight, making him or her a lyric, he or she can certainly attempt to add more weight by falsely darkening his or her tone, but this will be at the expense of his or her natural timbre and resonance. Likewise, a heavier voiced individual should not regularly sing with a lighter sounding voice quality that is not natural to his or her instrument. Whenever singers attempt to fake it by intentionally altering the sounds of their voices, they invite acoustic distortion and bad technique, both of which lead to vocal limitations and potential injury.

Otherwise, consider taking some voice lessons with a classical technique instructor who can get to know your voice well, and then make an accurate assessment of your technical skills and an eventual determination of your vocal Fach. (Teachers of classical technique are more likely than teachers of contemporary methods to have a solid background and good understanding of the process of correctly determining vocal Fach, since it is far more essential to the classical styles of singing that they commonly, though not exclusively, teach.)

Источники информации:

- http://kentamplinvocalacademy.com/2018/09/what-the-fach-what-is-your-vocal-type-2/

- http://towardsdatascience.com/voice-classification-using-deep-learning-with-python-6eddb9580381

- http://emastered.com/blog/types-of-singing-voices

- http://www.singwise.com/articles/how-to-determine-singing-range-and-vocal-fach-voice-type