How to draw wings

How to draw wings

How to Draw Wings

In this drawing lesson, we will show you how to draw wings. If you want to draw mythical characters (for example, Cupid), you will probably need the ability to work with wings.

Step 1

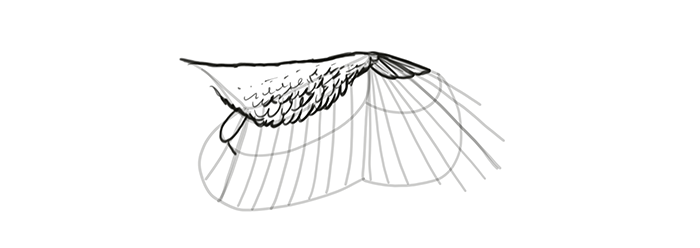

Firstly we will depict the contours of the upper part of these wings. Mark the noticeable bend in the medial parts of both figures.

Step 2

Draw the lower contours of the wings to get the completed silhouettes. The upper corners should be pointed as in our sample.

Step 3

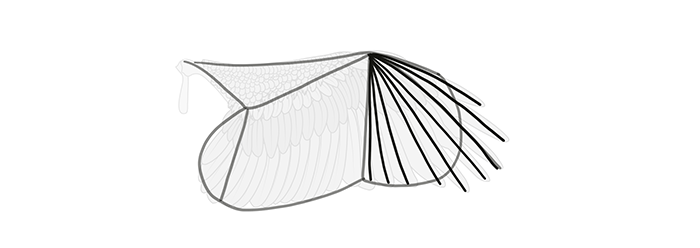

We depict radially diverging lines that cover almost the entire surface of the wings. Unpainted should only be areas similar to small wings that are located medially.

Step 4

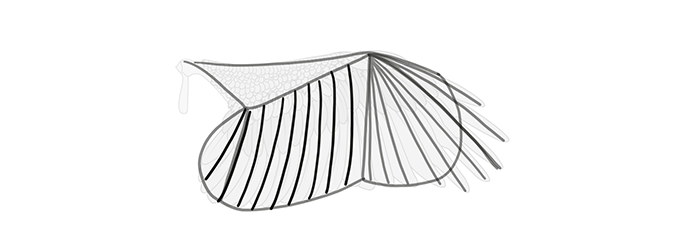

You think this will be a very difficult stage, right? In fact, we just need to depict the ovals in each gap between the lines from the previous step. Keep an eye on the symmetry as well as the difference in size and shape of these ovals.

Step 5

Repeat the previous step with minor changes. We also draw oval shapes, but now they should be smaller. Also these figures should be directed down.

Step 6

Now we are starting the stage in which we will depict the last row of oval shapes. We should depict the smallest figures of all that are in our drawing. Ovals that are located laterally should be directed upward.

Step 7

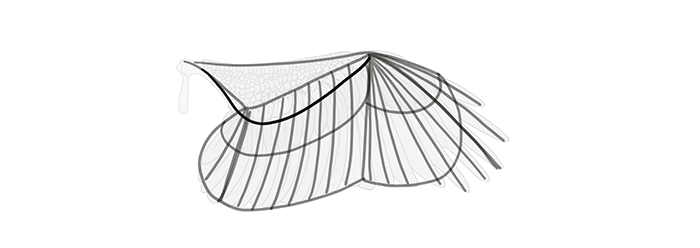

This will be the easiest step of the whole lesson, in fact. Here we need to depict smooth curved lines that follow the contours of the feathers. Only the most medial row of feathers has no lines.

Step 8

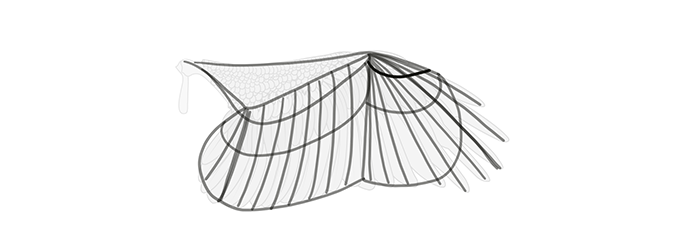

At this stage, we evaluate the shape of our wings and the symmetry of the pattern. Compare the segments of each wing and the difference in size. If you do not see inaccuracies or errors, you can proceed to the next step.

Step 9

Add some color. We decided to choose a light gray color for the wings. You can choose another color for these wings if you draw a character with dark or blue wings.

Do not forget to write your wishes in the comments. When creating new drawing guides, we focus on your preferences.

SketchBook Original: How to Draw Wings

This post has been originally commissioned for SketchBook Blog in 2016. After the site’s migration, the original is no longer available, but you can still access the content here. Enjoy!

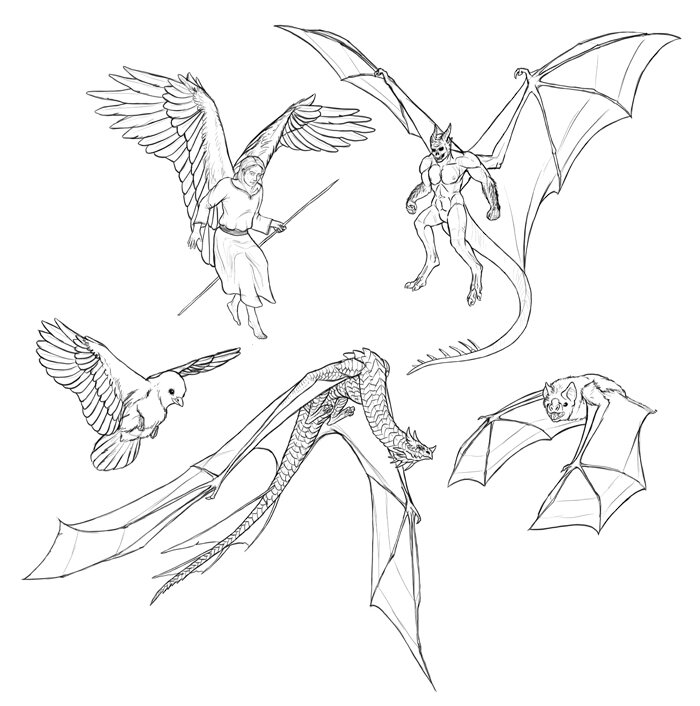

Angels and demons, dragons and griffins, they all have one thing in common—they have wings and they can fly. Flying creatures are incredibly beautiful, but they’re also quite difficult to draw. How are wings constructed? How do they work? How to draw all these feathers and the membrane? How to make the creature really fly, and not just flap its wings chaotically? In this tutorial I will show you it all, and you’ll also have a chance to animate your character!

You may also be interested in my newest tutorial about animating wings.

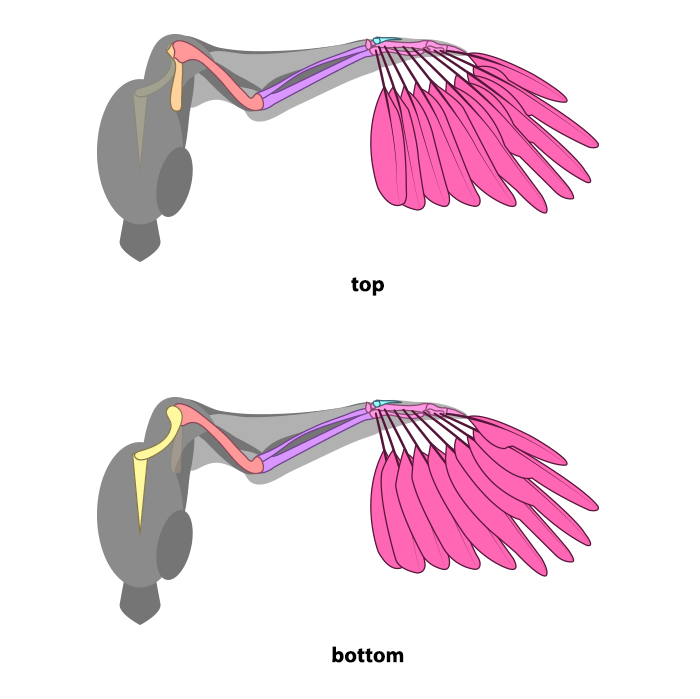

The Anatomy of a Bird Wing

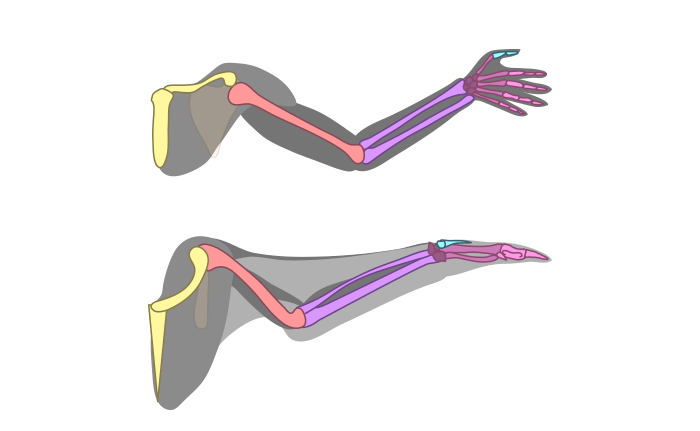

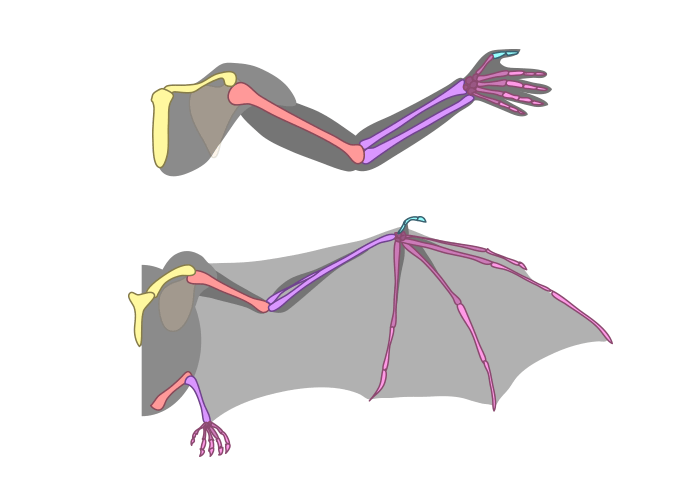

Let’s start with a diagram you might have seen before—the comparison of bones in a human arm and a bird wing. The similarities between them are very important to understand, because a wing is nothing else but a specialized arm with feathers sticking from it. They have the same joints, so you can simulate a movement of a wing by moving your arms.

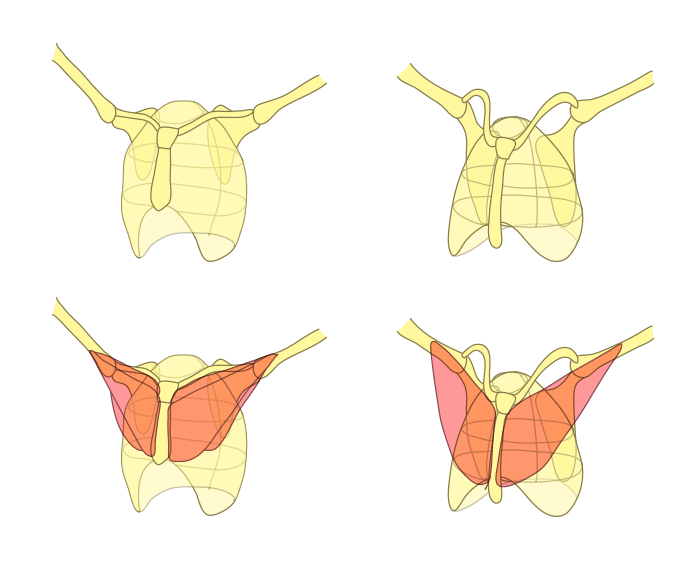

Powerful breast muscles are required for an active flight, and in birds these muscles are attached to a modified version of the sternum, called a keel. Why am I talking about it? Because wings are not only “planes of feathers”—they’re a whole structure growing from the body in a special, non-random way. Keep it in mind when designing winged creatures.

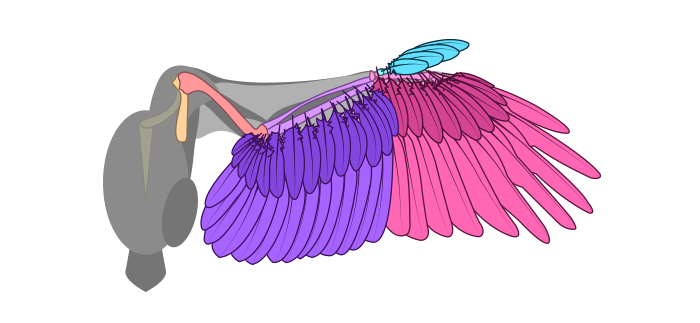

The feathers’ pattern seem complex and hard to memorize, but once you understand the specific layers, you’ll have no problems with it. So let’s tackle them one by one.

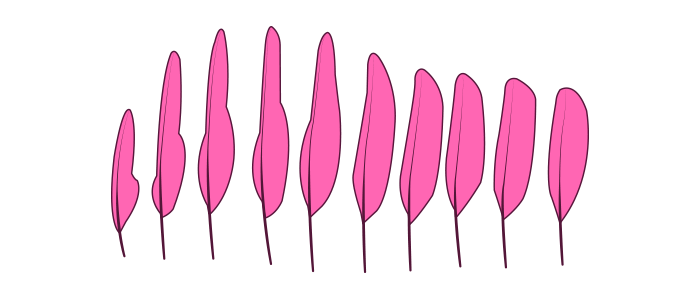

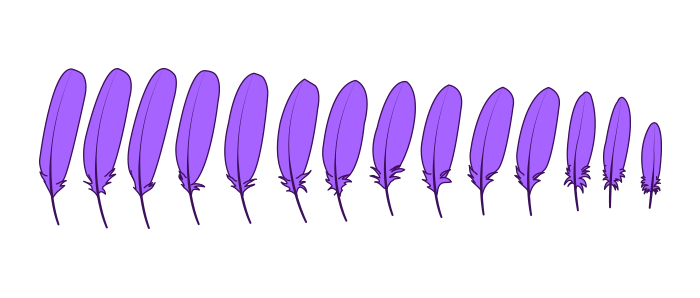

The primary feathers (also called primaries) are attached to the “hand”. They’re long and stiff, and some of them may be slotted—cut for a better maneuverability. No matter how long the wing, there’s usually ten of these feathers.

Primaries lie one upon each other, and this overlapping can be seen when they’re backlit—two layers of feather will be darker than one.

The “hand” bones are mostly merged, but they have some limited range of motion.

Let’s take a look at secondary feathers (secondaries) now. They’re wider than primaries and they’re never slotted. They seem to go to an opposite direction as well, enveloping the elbow and turning towards the body at that point. The number of these feathers depend on the length of the wing.

When wings are being folded, the feathers overlap each other following a rhythm of folding. When the bird keeps its wings close to the body, primaries are hidden under secondaries.

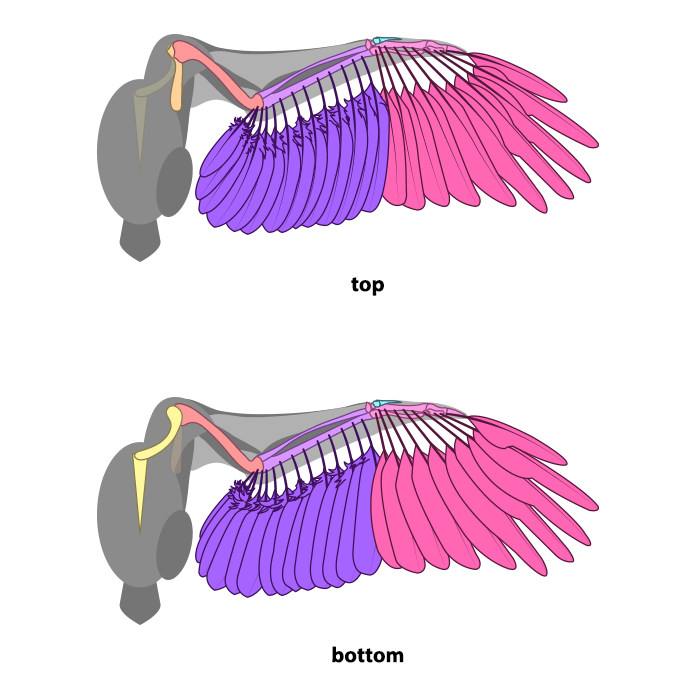

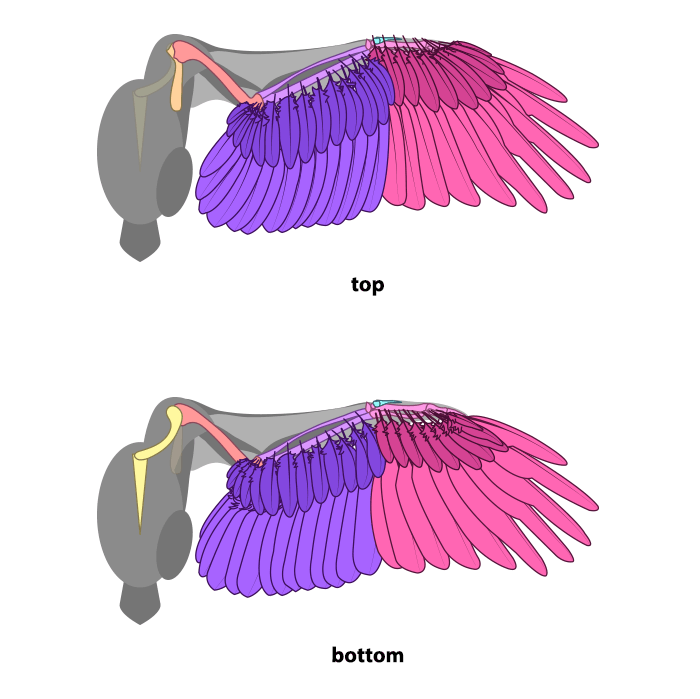

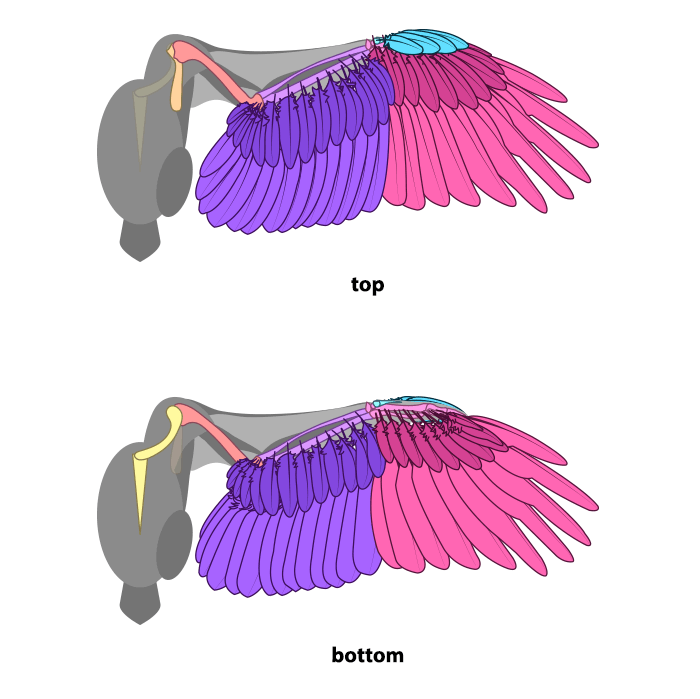

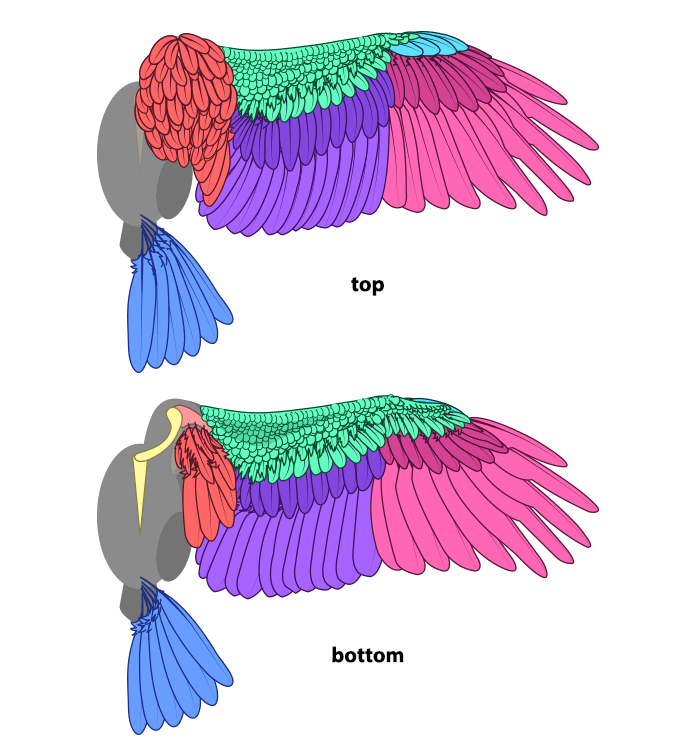

Both primaries and secondaries are covered with greater coverts. They’re like a smaller version of the feathers they cover. Each side of wing has its own layer of them, so this area will stay dark, even when the wing is backlit.

The “thumb” has its own cluster of feathers, called alula. It’s visible on the top side only.

Just like a normal thumb, alula can move, though not very much. It can be helpful in some precise maneuvers.

The shoulder and the wrist are connected with a tendon, and the whole area here is covered with skin. A lot of tiny feathers are attached to this skin: they’re called lesser coverts. On top of the wing median secondary coverts can also be found, but you can make them a part of lesser coverts in your drawing.

On the underside of the wing these feathers are very soft and almost non-distinguishable. You can sketch them quickly, leaving only a suggestion of feathers.

You can see there’s still some space between the wing and the body. It’s filled with scapulars (feathers growing from the area of shoulder blade), the mantle (a “cape” of feathers covering the back), and, on the underside, the axillaries (also called tertials, but they’re not true flight feathers. They grow from the armpit area).

How to Draw Bird Wings Step by Step

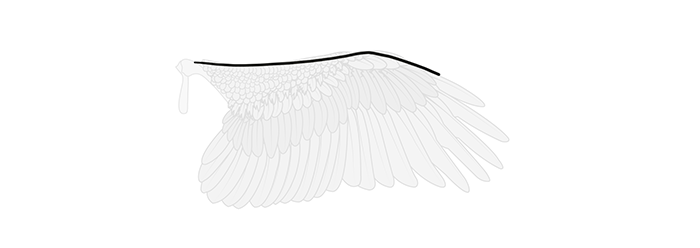

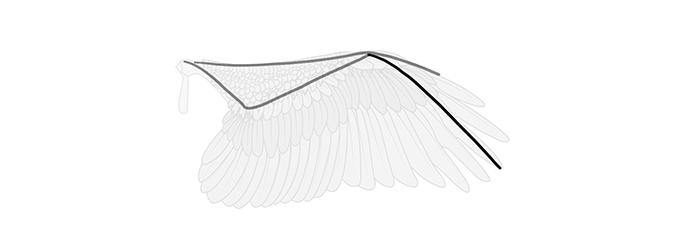

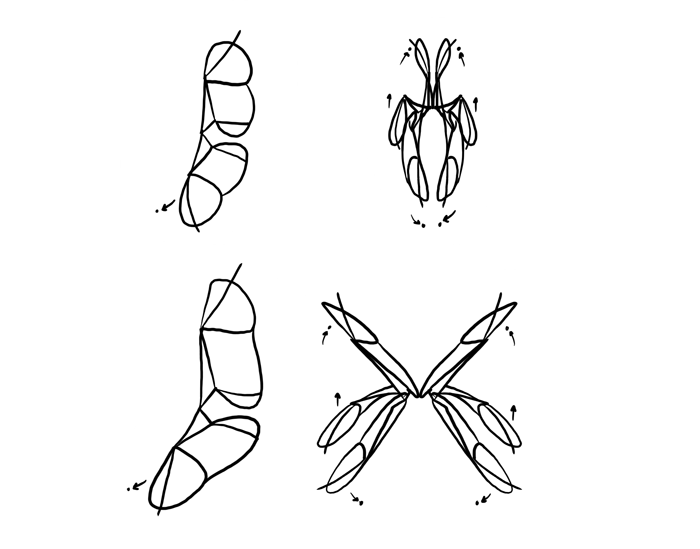

All this theory can be easily translated into a drawing. Start by sketching a line that will define the front edge of the wing. This will let you create a basic pose for the wings without caring about the bones yet. Don’t make the hand area any longer than the level of primary coverts.

Now you can add the arm and the forearm. Anatomically, they should be almost equal in length, but usually a half of the arm is hidden in the body, so you can make it much shorter for simplicity’s sake.

Now draw the longest primary feather. It’s usually somewhere in the middle.

Outline the edge of the primaries, as if they got shorter when getting close to the tip of the finger.

Draw the length of the secondaries at the elbow. Make it facing the body.

Outline the secondaries, along with this characteristic rounding near the body.

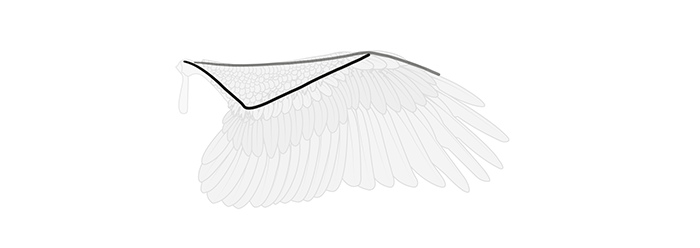

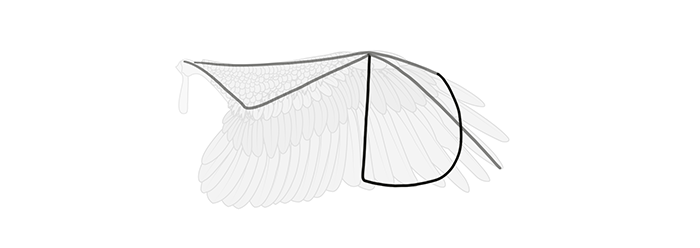

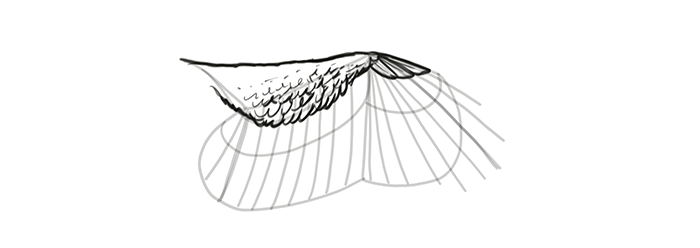

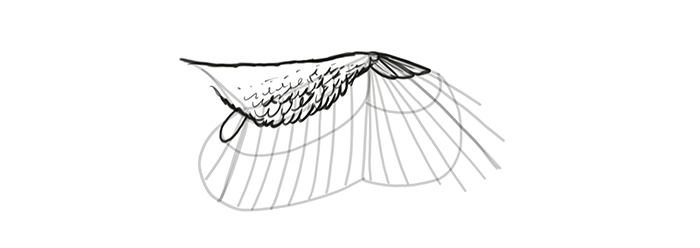

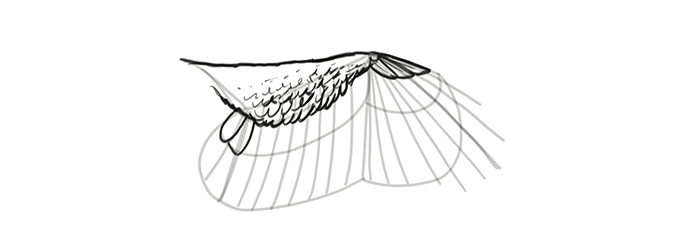

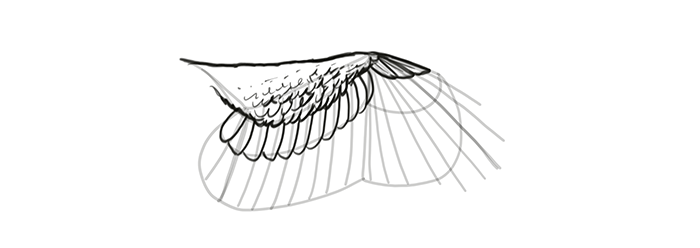

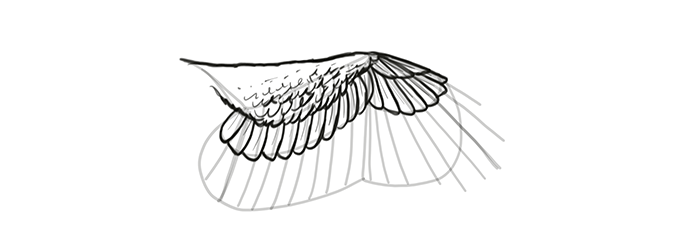

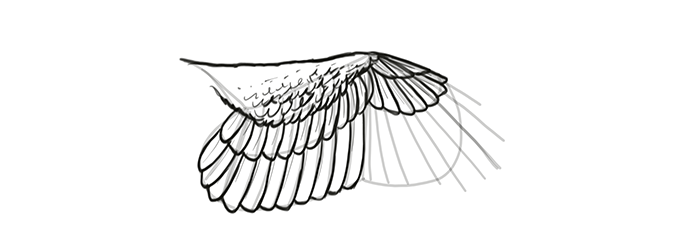

Time for the actual feathers. First the primaries…

… then the secondaries. Notice the characteristic rhythm!

Finally, cover the feathers with the greater and lesser coverts, and add the alula.

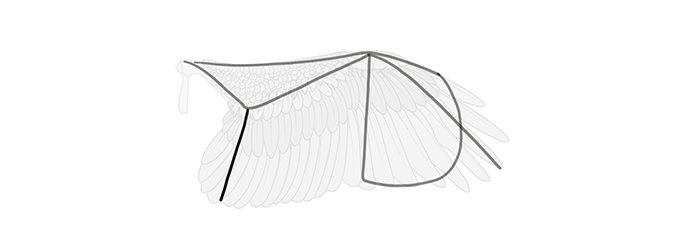

The wing is fully constructed! Now you just need to draw the actual feathers on this base. It’s good to start from the top:

When you draw the row of feathers, keep in mind which side you’re drawing. Start drawing the closest to the body on the upperwing, and the farthest from it on the underwing.

Don’t make the feathers completely round. They should make neat rows together.

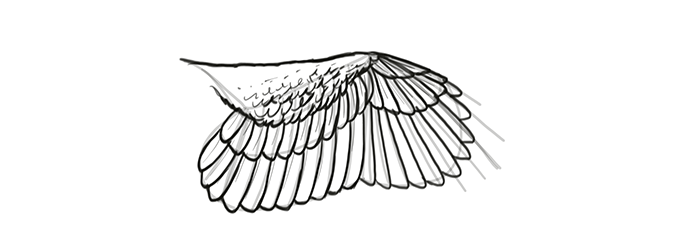

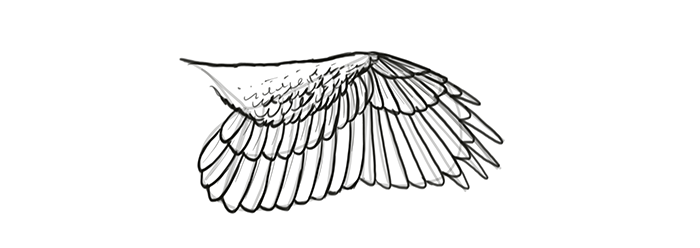

Secondaries can be drawn the same way. Keep in mind they’re big and overlapping, so if you want to draw the rachis, don’t place it in the middle of each feather.

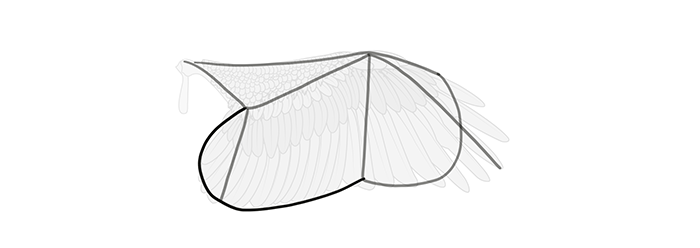

Slotted feathers can be drawn by following the rhythm…

… and then adding long, narrow tips to a part of the feathers.

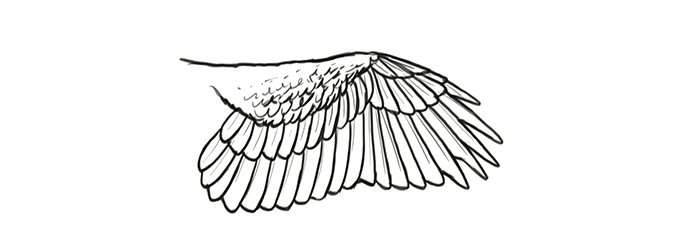

The wing is done!

Common Mistakes

Most mistakes in drawing come from trying to draw from memory something you don’t quite remember (and not wanting to use a reference). Stylization is one thing, but if you were going for realism and failed, this is not style—it’s a mistake. Let’s see what’s wrong with these wings.

How to Animate a Flying Bird and Draw Wings in Motion

The pose of wings is dictated by their function and the current action. If you want to draw wings in all poses from imagination, you need to understand the whole process of flying and how wings make it possible. Looking at a photo of a flying bird as a reference is only a temporary solution, and memorizing a few poses will limit your creativity as well. The best way to understand the rules of flight is to create your own animation, step by step, to see exactly how the wing moves and changes shape in the process.

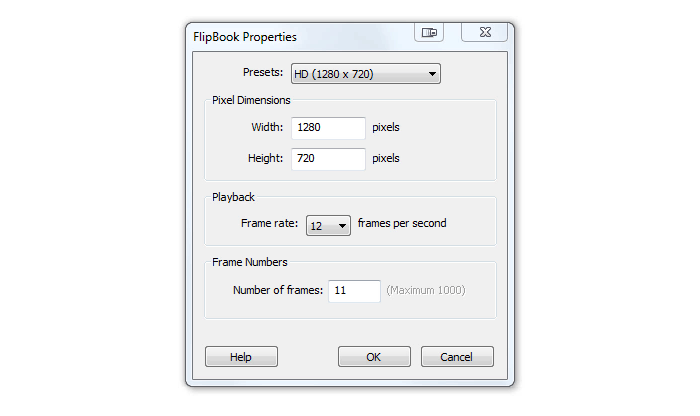

How to create your own animation? You can use the FlipBook feature of SketchBook Pro. Here’s a quick introduction. Go to File > New FlipBook > New Empty FlipBook. Choose a resolution, a low frame rate, and 11 for the Number of frames.

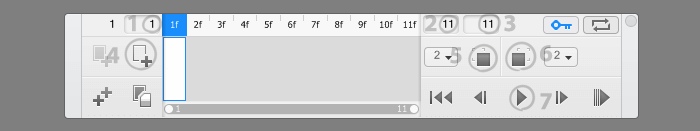

FlipBook is extremely simple and intuitive, so you may not even need this, but here’s a quick explanation of the functions in case you’re confused:

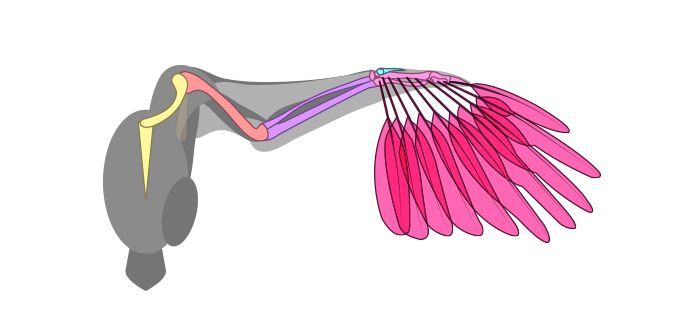

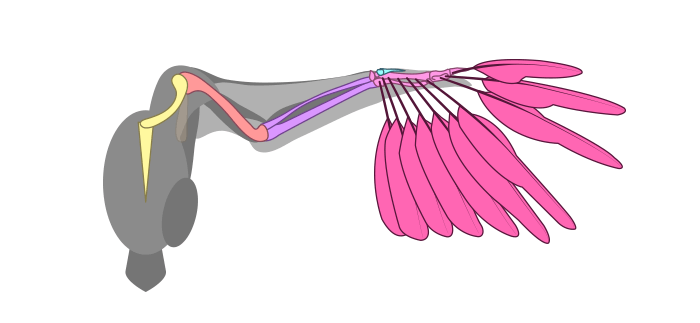

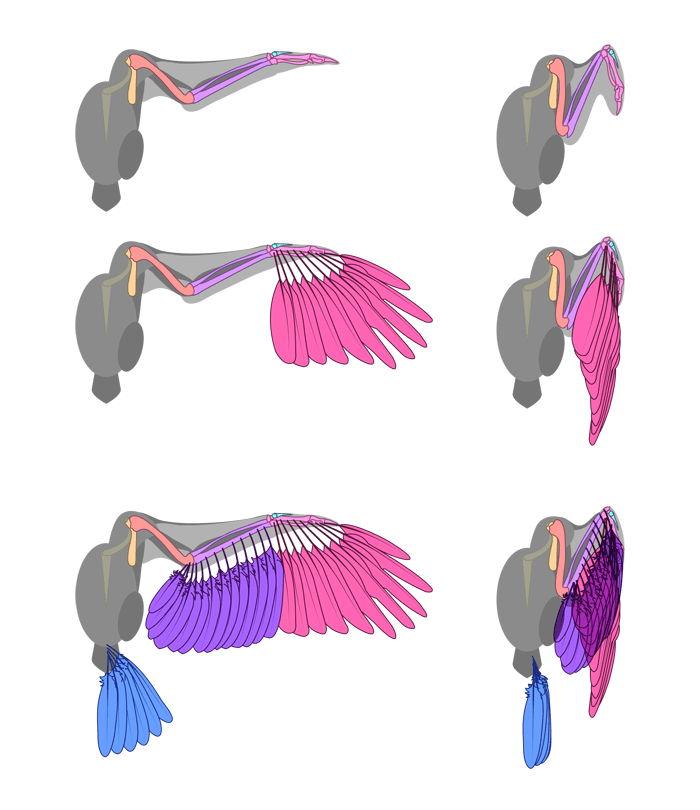

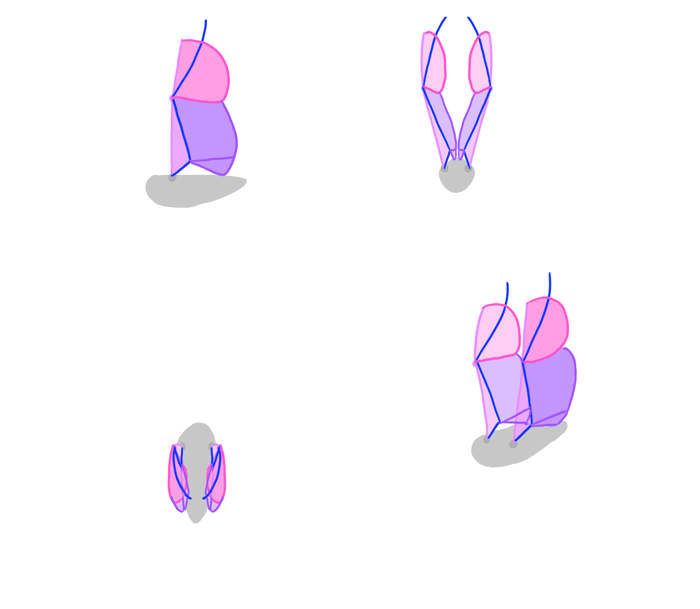

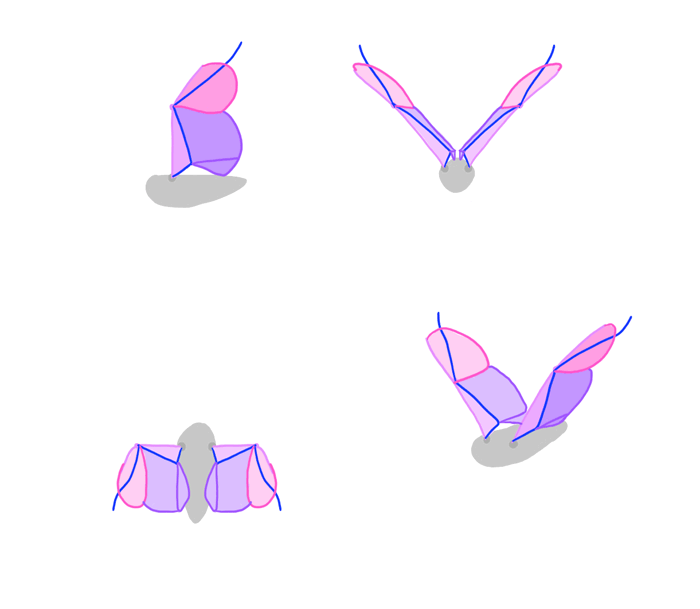

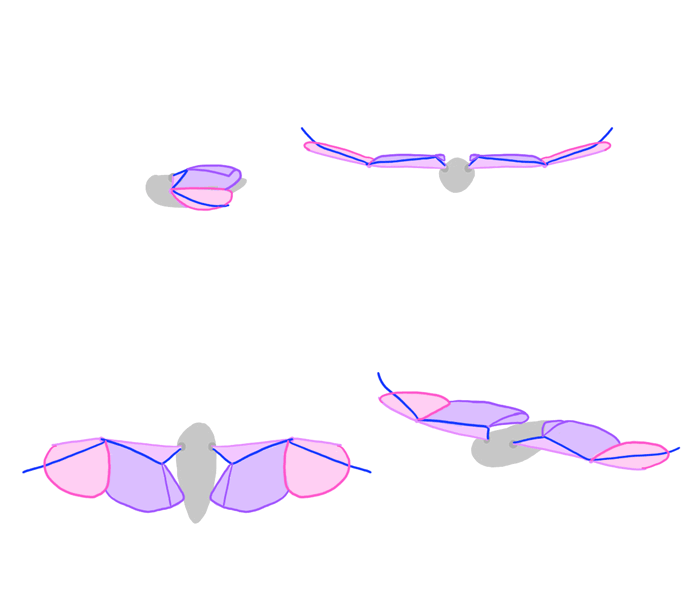

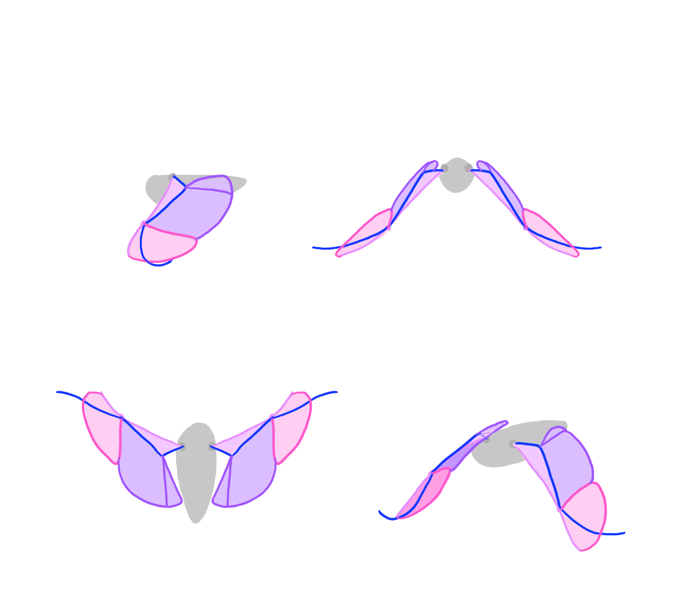

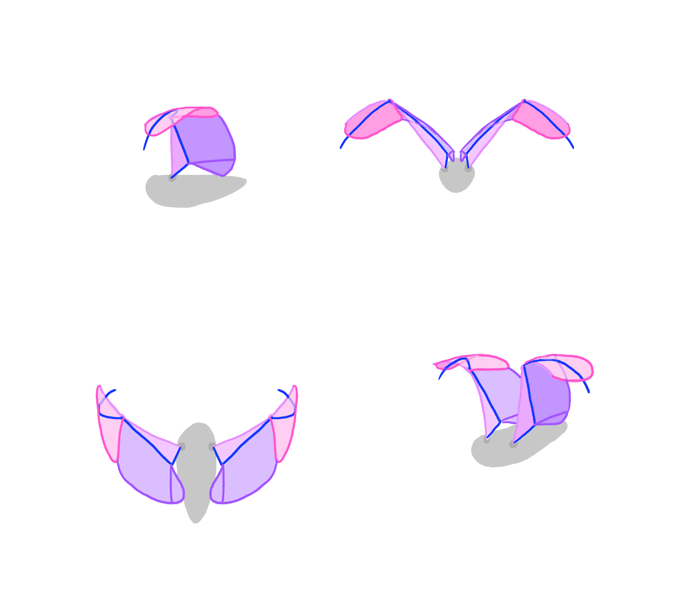

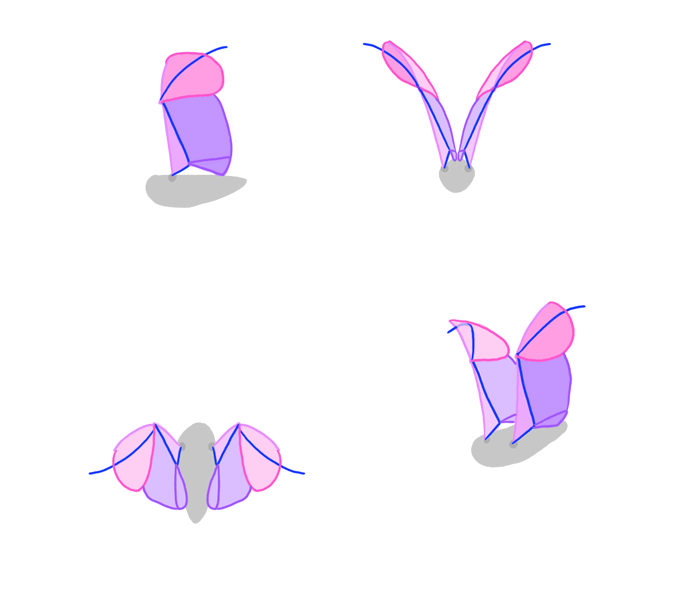

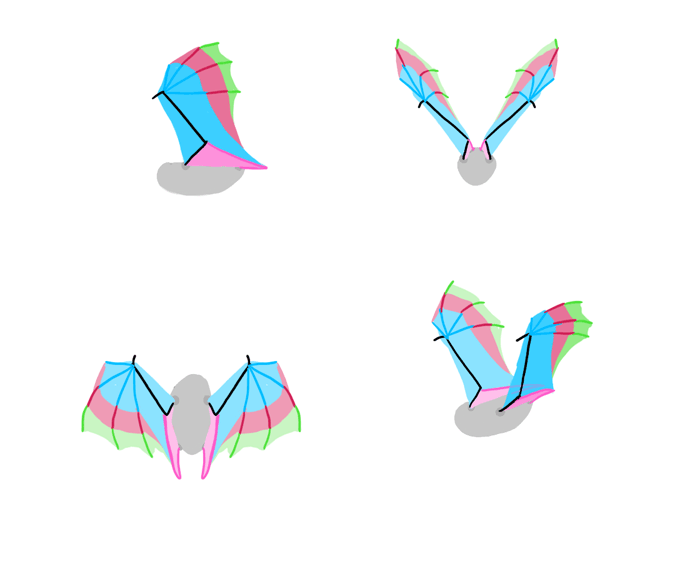

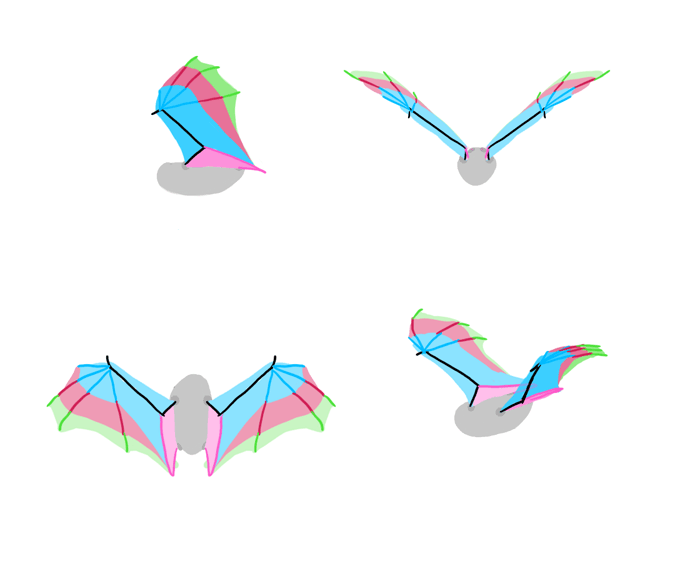

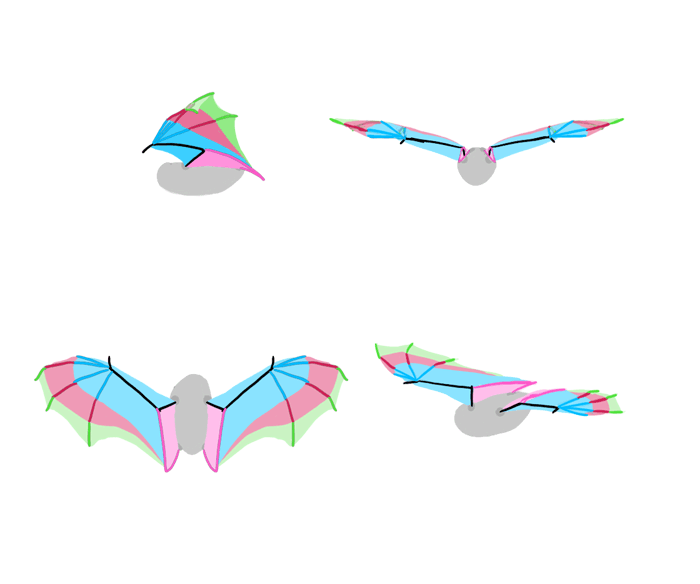

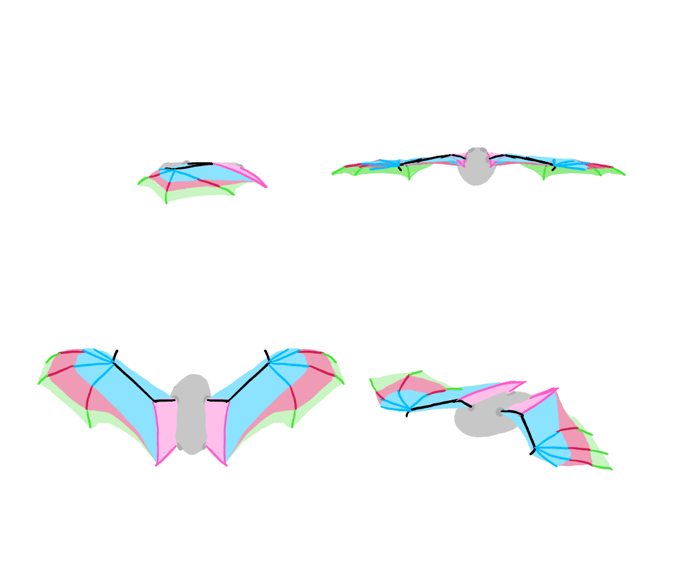

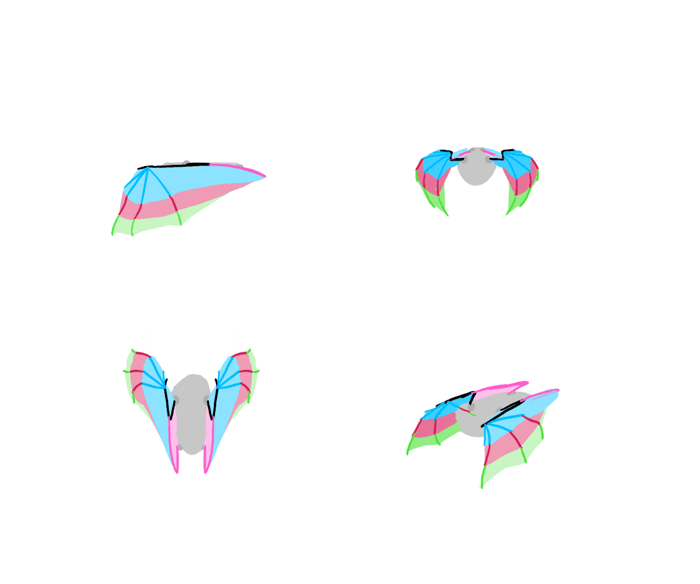

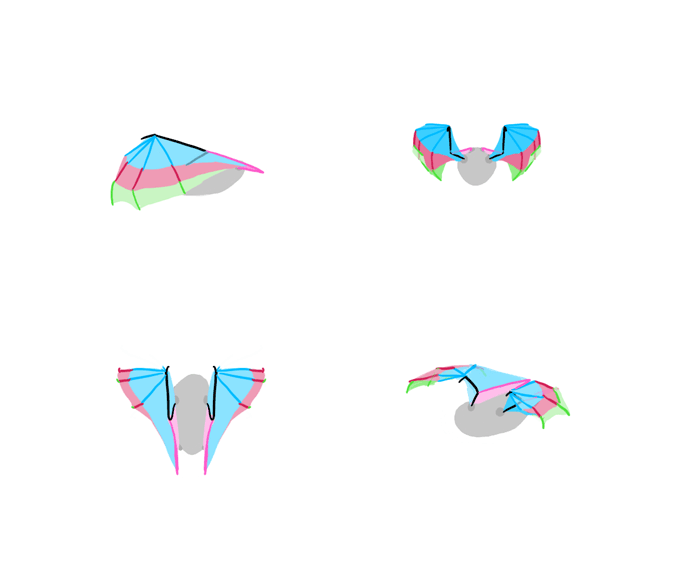

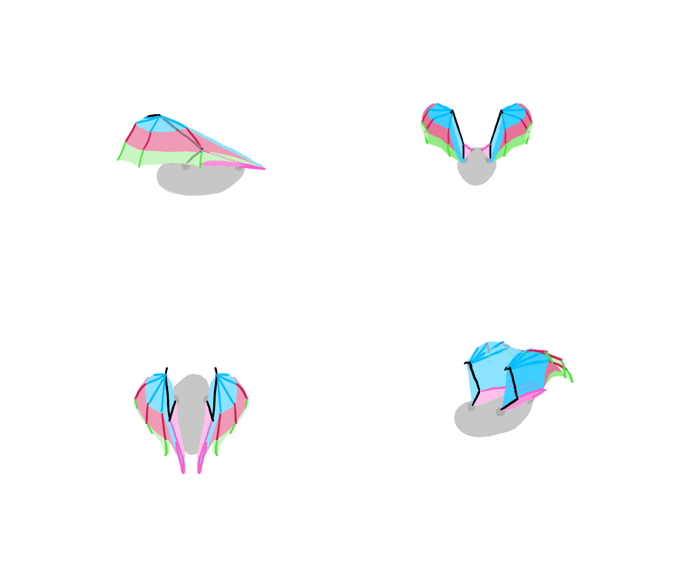

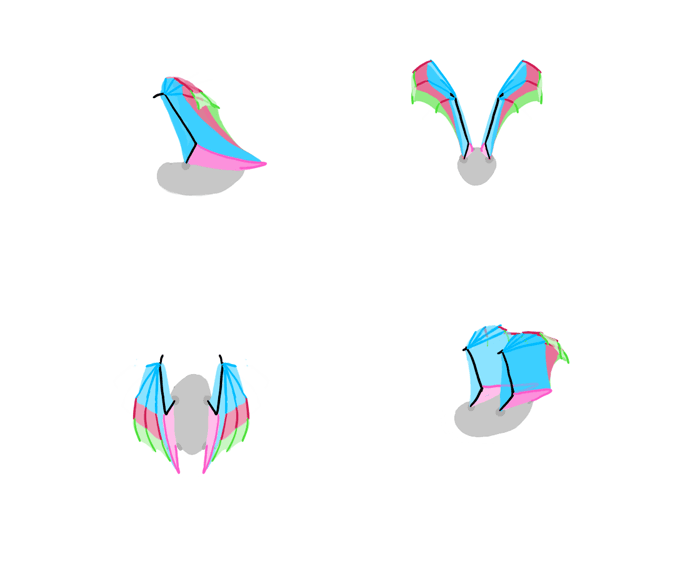

Let’s animate the wings now! Since they move in three dimensions, I’m going to present four views at once, so that you could see exactly what happens. Feel free to choose any of them for your animation. You can use your own arms as a reference to visualize what I’m describing.

Flight is all about pushing the air down, so this is where we start. The wings are straightened and flat, ready to begin the downstroke phase. All the feathers make a continuous surface without any gaps.

The wings are pushing the air down…

… lower and lower…

… until they become completely flat on the level of the body.

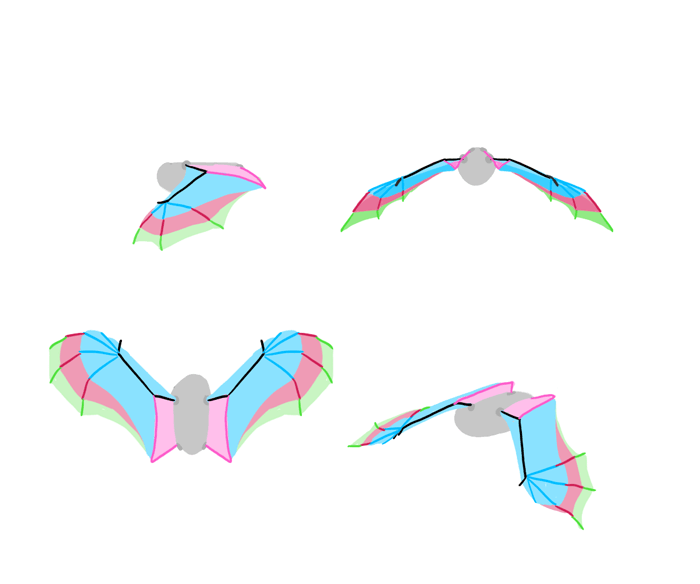

This was the easy part. Now the deep downstroke begins. The bird moves the wings down… and forward!

In the last step of downstroke the wings are straightened under the bird’s body.

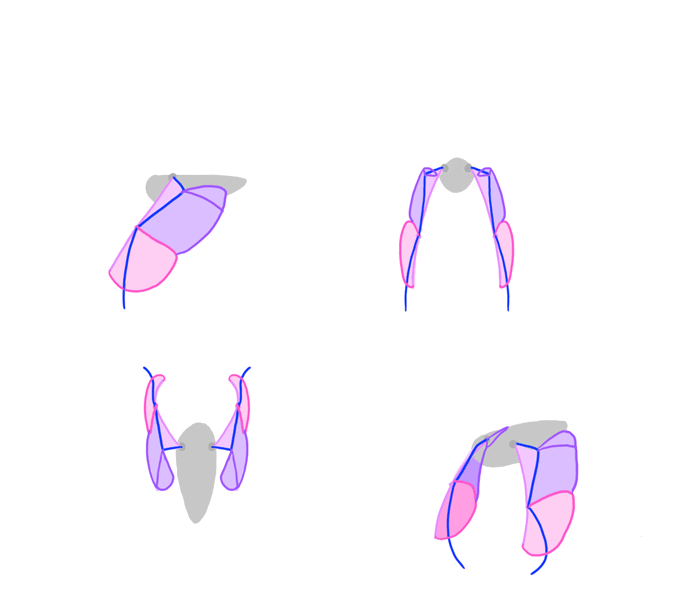

When there’s nothing more to push, the wings must be brought back up for another downstroke. This must be done fast, because the bird is actually falling a little during the upstroke. That’s why the bird is folding the wings on the way up, to reduce air resistance. This is the part where individual primary feathers can be spread as well—additional gaps help!

Notice how the wings are kept as close to the body as possible.

The wings are being unfolded part by part—first secondaries go to their straightened position, then primaries.

Finally, the primaries are straightened as well and the bird is ready for another downstroke!

And here’s a whole animation:

Every flight cycle doesn’t look the same. Smaller wings will flap faster, with more extreme positions (deep down, far up, folded close to the body), but they will also require less pushing forward. Big wings push more strongly forward, but they also have less extreme positions during the process.

Now you know the theory behind the bird wings, but theory is not enough! Take your time to test what you have learned by drawing simplified wings from many different references. There are three exercises you can try here:

The Anatomy of a Bat Wing

But birds aren’t the only flying creatures on Earth. Let’s take a look at the only truly flying mammals: bats.

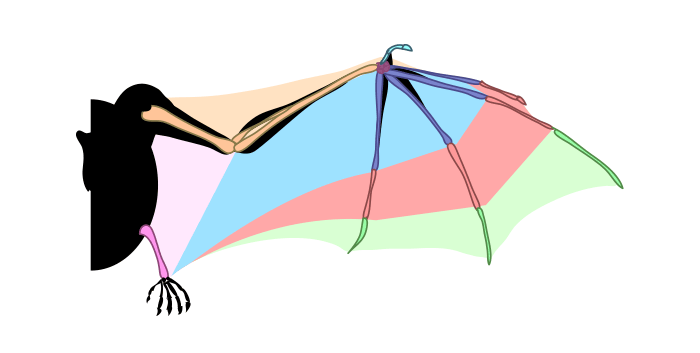

Because bats are mammals, they’re more similar to humans than birds. Their wings are actually elongated fingers with a membrane in between. The membrane is also connected to the hind limb, so that it can be actively stretched.

The chest of a bat is also similar to a human chest. It’s simply much bigger in terms of proportion. In opposition to birds, bat can flap their wings by moving whole shoulders, not only arms (notice the clavicles and their potential range of motion).

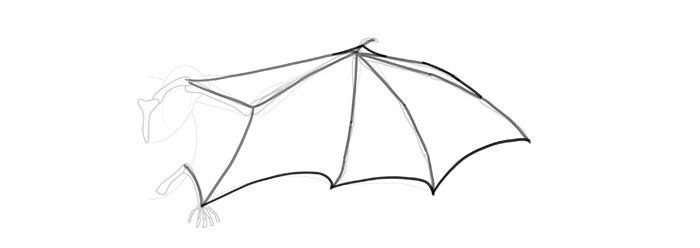

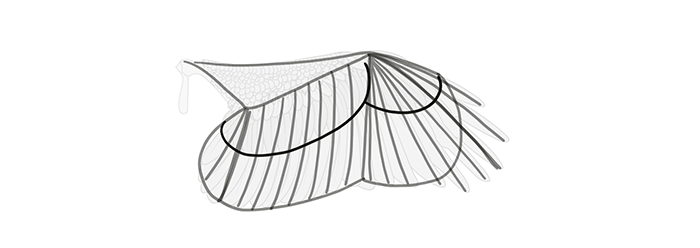

The membrane is one piece od skin, but for our purposes we can distinguish special areas of stretching. By drawing “stretching lines” in these areas you’ll make the wings look detailed very quickly.

How to Draw Bat Wings Step by Step

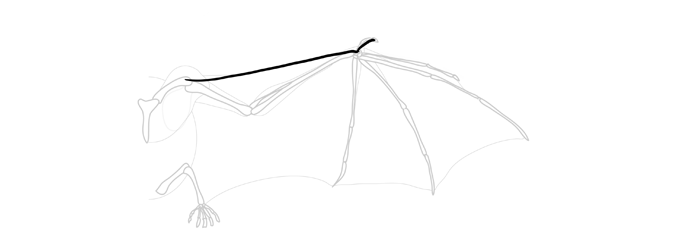

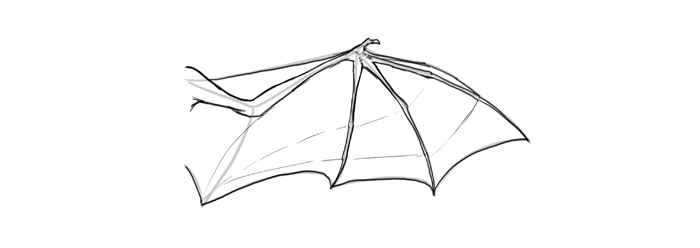

Bat wings are pretty easy to draw once you know their structure. Start with the edge of the wing and end it with a thumb. This will let you define the general position of the wing.

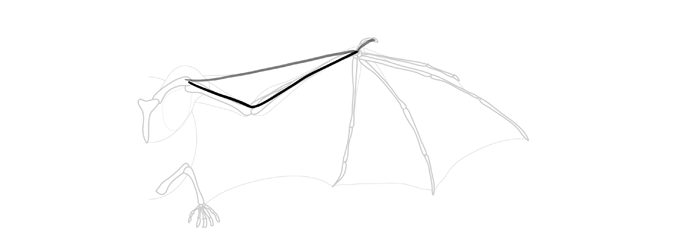

Create a long triangle to draw the whole arm.

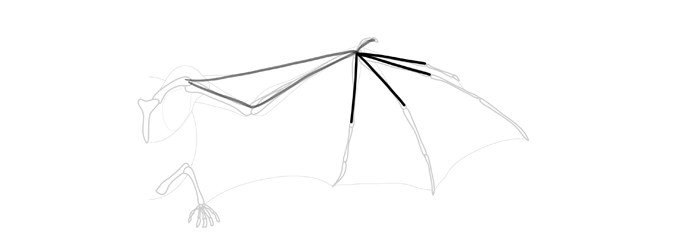

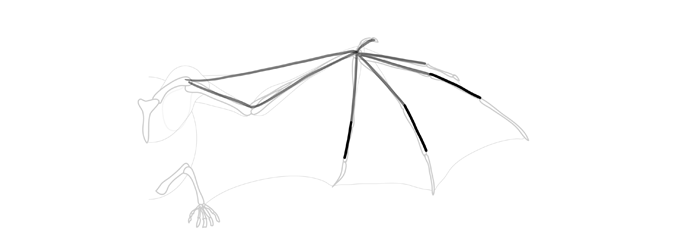

Now draw the fingers, part by part:

This part is the thinnest and the most flexible.

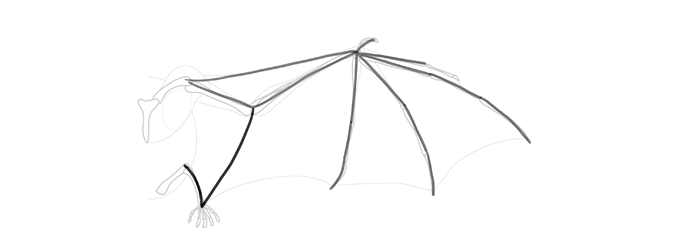

Don’t forget to connect the membrane with the legs.

Finish the outline of the membrane. Notice the gentle arcs between the fingers.

Finish the drawing by adding the details.

Common Mistakes

Many artists draw membranous wings wrong, stating that if they’re demon wings/dragon wings then nobody knows what they should look like. However, after this tutorial you should already know that wings are not just a decoration—they have a certain function and their shape reflects that function. Again, drawing decorative wings is not a mistake in itself, but if you want to draw realistically, here’s what you must avoid:

How to Animate a Flying Bat and Draw Wings in Motion

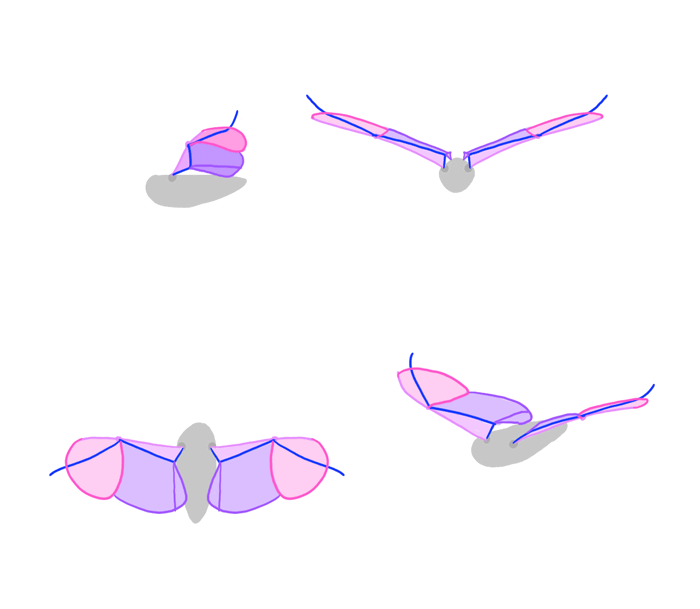

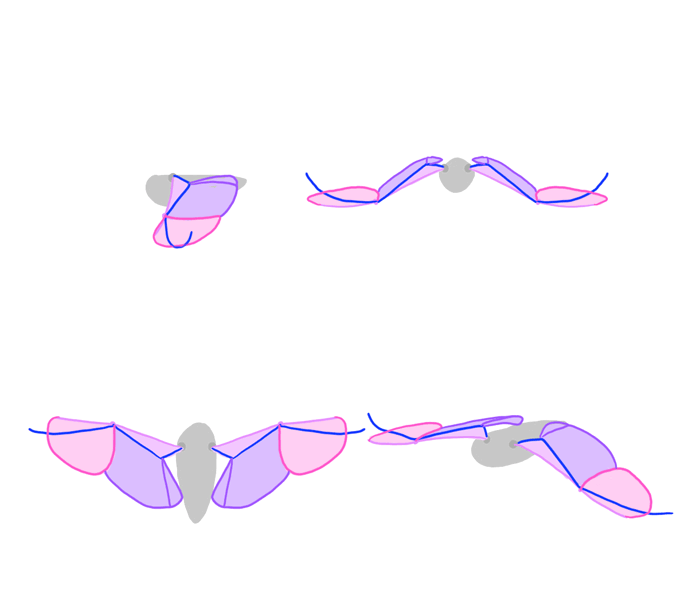

Bird or bat, their flight is still about pushing the air, and the whole process looks pretty similar. However, a bat’s fingers are far more flexible than bird’s feathers, so they take an active part in the process. Also, while birds flap with their whole arms, bats flap with their fingers instead. Let’s take a closer look.

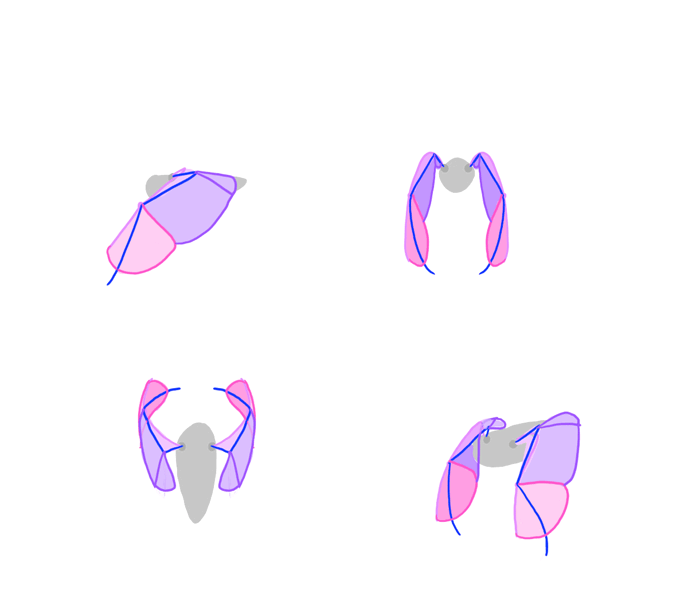

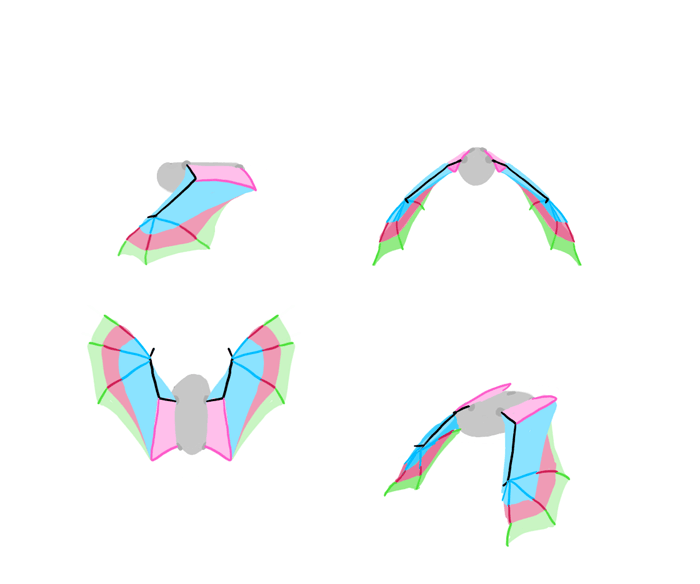

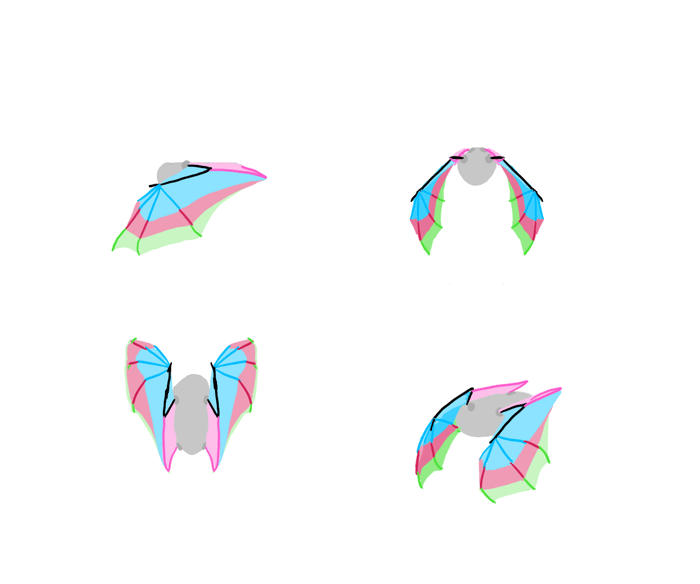

Bats flap their wings faster and more continuously then birds (they’re not too good at gliding), so wings are not brought too far over the back at the beginning of the downstroke—the flaps are shallow and quick. In this step the fingers are outstretched to enlarge the area of the membrane.

So far so good—no different than in birds.

Notice that the wings go forward much sooner!

While the wings go down and forward, the fingers rotate down as well, creating more lift—this is what birds cannot do with their immobile feathers! Also, notice how each phalange (finger bone) moves individually within its limits—that’s why it’s so important to draw them separately and not as simple long lines bending like feathers.

Here we have the end of the shallow downstroke—no need to push any farther, because the bat is able to generate some more lift during the upstroke as well.

Time for the upstroke. Just like with the birds, the bat is folding its wings on the way up, but in a more precise way—phalange after phalange. This way the upper part of the wing goes up, while the lower one keeps on pushing. For this to work, the surface of the wing must be facing forward as long as possible.

Notice how the tips of fingers keep pointing forward, even when the whole wing is going back.

Finally, the whole wing gets straightened, phalange after phalange, from the base to the tips, to create a flat surface for another downstroke.

Here’s the whole animation. Can you see the difference?

Again, regular practice is needed to draw bat wings from imagination. Use the same exercises I described for birds.

How to Draw Wings Step by Step

OK, that was theory. But how to actually draw wings? Let me show you how I do it, and feel free to create your own method from what you learn.

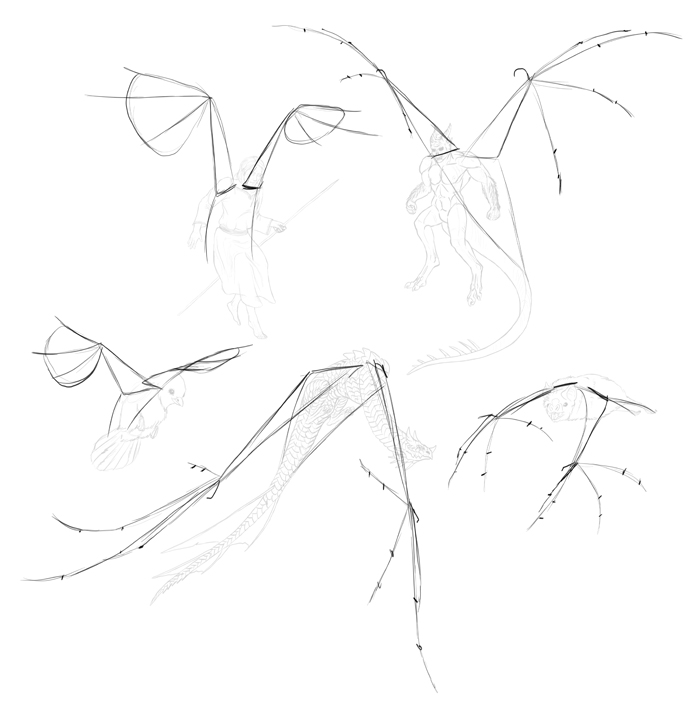

Step 1

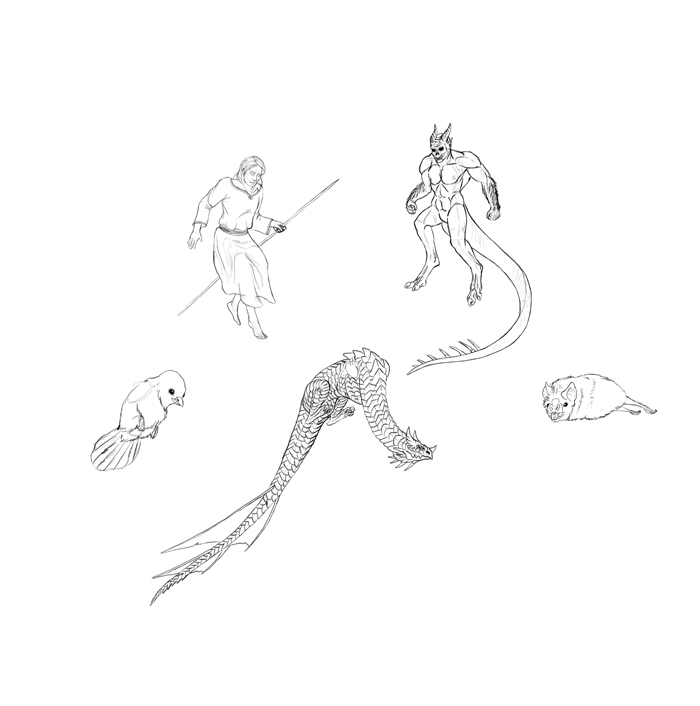

I’ve prepared the bodies of a few creatures that I want to add wings to: an angel, a demon, a bird, a dragon, and a bat. For the sake of this presentation they’re finished drawings, but normally I would draw them along with the wings—this way I could change the pose of the body if the wings turned out to require it.

Step 2

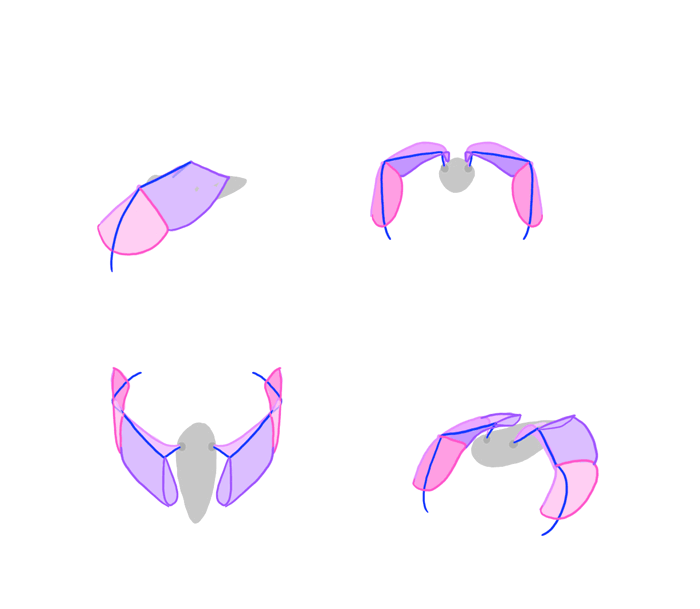

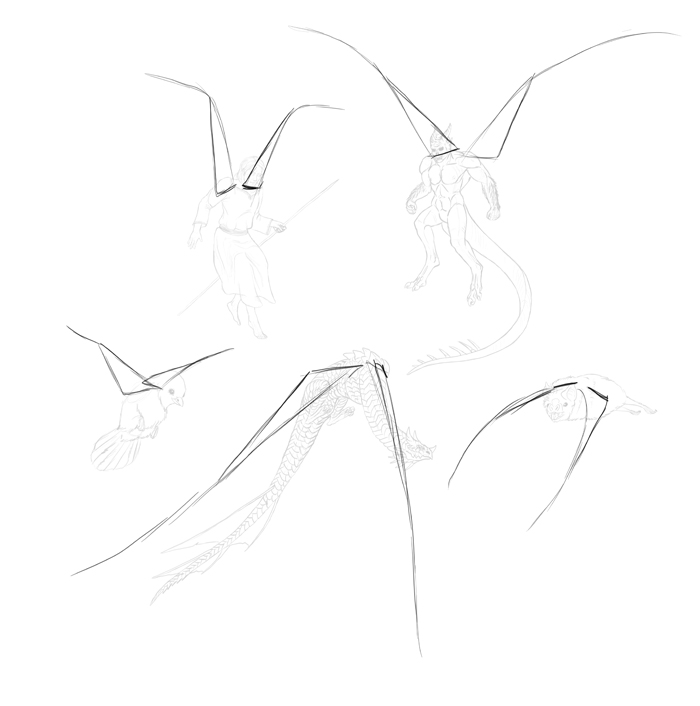

Start with a very general pose of the wings. First sketch a direction, and then bend the wings according to the phase of flight they are in. As you know now, downstroke and upstroke are very different!

Step 3

Add the arms. Make sure you follow the perspective of the body.

Step 4

Draw the long primaries (in case of feathered wings) and the fingers (in case of membranous wings). Again, perspective is very important here. If you’re having problems with this step, it may mean you need to spend some more time practicing perspective.

Step 5

Draw a line from the elbow pointing towards the body. These lines really help with perspective.

Step 6

Draw the finger joints in the membranous wings, and the outline of primaries in the feathered wings.

Step 7

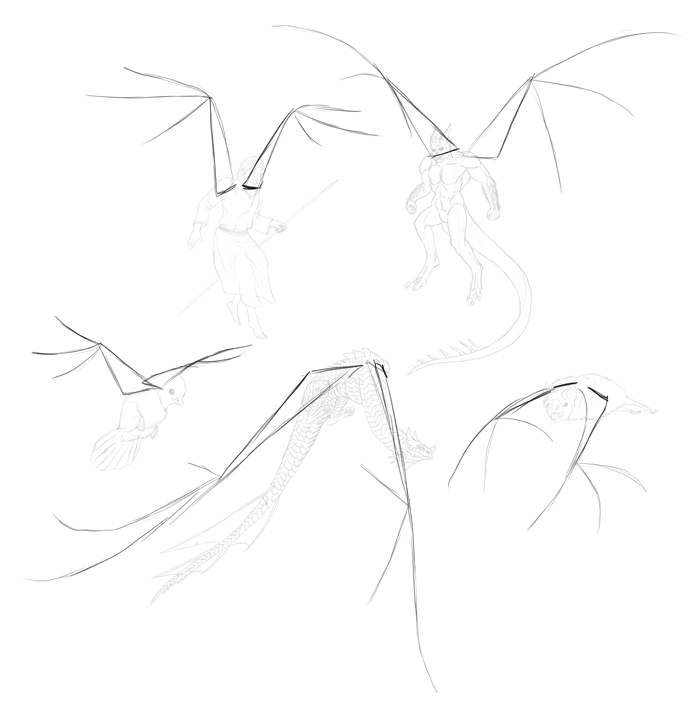

Add the secondaries and the membrane.

Step 8

Sketch the direction of the feathers, and add some volume to the arms in membranous wings.

Step 9

FInally, finish the drawing with all the details.

That’s All!

I’ve shown you how bird and bat wings are constructed, and how to draw wings in flight. But before you go straight to all your angels and dragons, take your time to practice drawing real birds and real bats—different sizes, different species, different poses. This is the only way to draw from imagination, without having to come back here all the time for a reference. Though, I won’t mind if you do!

SketchBook Original: How to Draw LizardsPrevious Article

Digital Drawing for Beginners: Best Program for Digital DrawingNext Article

You May Also Like

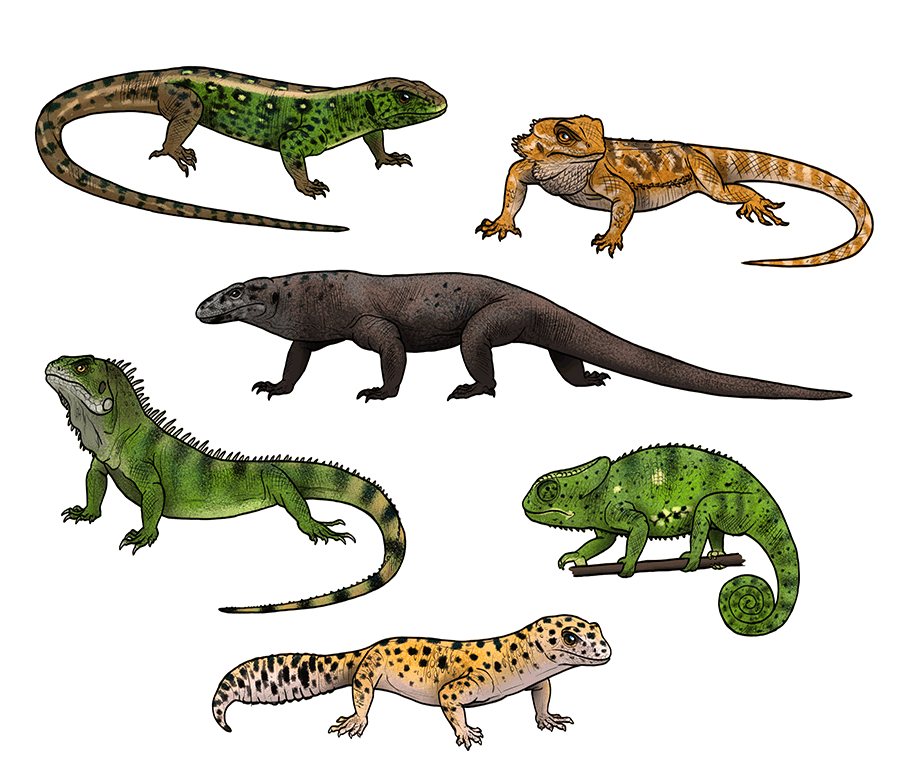

SketchBook Original: How to Draw Lizards

This post has been originally commissioned for SketchBook Blog in 2016. After the site’s migration, the original is no longer available, but you can still access the content here. Enjoy! We have learned how to draw many animals so far, dogs, cats, even wolves, but now it’s time to tackle the real dragons – lizards!…

About the author

Monika Zagrobelna : Learning how to draw and paint is my passion. And I love sharing my knowledge with others!

How to Draw Angel Wings

In this tutorial I will show you how to draw wings on the back of a human, creating an angel. Angels, though seen as spiritual rather than material, are pictured as winged humans. But wings are not simply an appendix growing out of the shoulder blades—they’re specialized arms. So a typical angel has three pairs of limbs!

So how to draw realistic angel wings? You need to dive a little into human and bird anatomy, not only mixing the bones and muscles visually, but also keeping their function in mind. So in this tutorial I will show you not only how to draw wings, or angel wings, but how to draw a realistic angel as well.

This tutorial can be complemented by the tutorials below. They dive deeper into the subject, providing terminology and more advanced knowledge.

Of course, if you simply need to draw a pair of angel wings, you can safely skip the anatomy part—the step-by-step instructions will be still easy to follow!

1. Comparative Anatomy of Human Arms and Bird Wings

Human Arm Anatomy

Let’s start with human anatomy, as you’re already quite familiar with it. Arms are attached to a structure called the pectoral girdle—the shoulder blades and the clavicles. This gives the arms a wide range of movement. A big muscle, called pectoralis, powers the shoulder—it’s attached to the sternum.

Bird Wing Anatomy

All clear? Let’s take a look at a bird now. Birds have a pectoral girdle as well, although it’s a little more complex: the clavicles are fused into a structure called the furcula (or wishbone) that works like a spring, and their function is taken over by a special bone called the coracoid (absent in humans). Because a birds need much more power in their arms than humans, their shoulders are powered by huge pectoral muscles connected to a massive sternum.

As you can see, wings are not simply arm bones—they’re a complex structure of pectoral girdle, arms, and breast muscles. That part starting at the shoulder is the most visible, but real, functional wings need more than this.

Here’s a quick visual comparison of both structures:

Winged Human Anatomy

You’ve probably noticed two problems here. One, we need to fit two pairs of limbs with separate shoulder blades and clavicles on one chest (if each pair is supposed to move separately). Two, the sternum must be huge, with space both for huge wing-pectorals and smaller shoulder-pectorals. So what do we do?

There are many ways to solve these problems, each equally fantastic. It’s neither possible nor useful to have two pairs of limbs so close to each other, so whatever solution we come up with, it will be only a pseudo-realistic rendition of impossible anatomy. But it’s still better than simply sticking some wings to the back!

Here’s my idea: the sternum is enlarged, with two layers of pectorals attached to it. The human-clavicles reach lower and are more curved, to leave space for the coracoid of the wing. The bird clavicles are removed—not all flying birds have them, so we can assume they’re not necessary for flight. The bird-pectoral muscle is still very big, covering the front of the torso.

The extra pair of shoulder blades has been placed between the human ones—fortunately, bird scapulae are narrow and can be curved to fit this placement. The wings start behind the original shoulders, slightly above them.

In this configuration, each pair of limbs can move separately, and the whole structure looks quite convincing—though in reality it’s not enough for a powered flight!

2. How to Draw the Anatomy of a Winged Human

If you want to draw an angel, or simply a winged human, you need to modify their chest first. It’s not necessary, of course, but it will add to the realism. I used this photo of a shirtless, muscular man as my model. He looks perfect for this purpose!

First, I added the fake bones inside the chest, with coracoids landing somewhere behind the shoulder-neck muscles. I tried to keep the sternum big, but not absurdly so (though it would be more convincing this way!).

Now, I attached the muscles to the bones, using the real muscles as a reference where possible.

After I turned the photo into a piece of line art, the new anatomy merged nicely with the original one.

If you need a reference for both the front and back view of a winged man, feel free to use these:

You can also simply copy these drawings to follow the rest of the tutorial.

3. How to Draw the Structure of the Wings

Step 1

Draw the basic rhythm of the wings. Forget the anatomy for a moment—just sketch a shadow of what the wings are supposed to look like in the end.

Step 2

Draw the arm and the forearm, creating a triangle under this basic curve.

Step 3

Add the «finger». It bends a little somewhere in the middle, so you can use it to create the pose you need.

Step 4

Draw a line separating the primary feathers from the secondary ones. It should be shorter than the forearm.

Step 5

There are usually ten primary feathers. Mark the «finger» to create space for each. Make the markings more spread out in the farther half.

Step 6

Draw the longest primary feather, starting at point 9.

Step 7

Draw a curve that will create the basic shape of the primaries. It should be like a section of a circle, suddenly turning towards the wrist.

Step 8

Draw the first five primary feathers.

Step 9

Draw the other three primaries—these can go outside the curve, getting more similar to the longest primary in length.

Step 10

The secondary feathers should turn towards the body. Draw the last one.

Step 11

Draw the curve of the secondaries.

Step 12

Draw the secondaries. No need to count them—just draw them in a similar rhythm, until you fill the area. No need to draw them in the front-folded view, though—they’re behind the folded primaries here.

4. How to Draw Angel Feathers

Step 1

Outline half of the primaries. The part inside the boundaries of the curve should be round, and the one outside more narrow. That’s how you create the characteristic slotted feathers.

Step 2

Draw the other half of the primaries. This part should be closer to the rachis.

Step 3

Outline the secondaries now in a similar way. No slotting here!

Step 4

Both primaries and secondaries are covered by greater coverts. They should cover the shafts of the feathers. Plan their length first. Keep in mind that the coverts are placed separately both in the front and in the back!

Step 5

Sketch the boundary for these coverts. It should mimic the rhythm of the feathers it covers.

Step 6

Draw the covert feathers.

Step 7

There are also lesser coverts covering the greater coverts. Draw them the same way, except this time avoid the back of the primaries.

Step 8

Additionally, there’s also a structure called the alula—a clump of feathers attached to the thumb. It covers the wing in the back, but a part of it can be visible in the front as well, when the thumb is «open».

Step 9

The space between the flight feathers and the body is filled with scapulars (in the back) and tertials (in the front).

Step 10

Finally, fill the rest of the wing with tiny covert feathers.

Step 11

The wings, when folded, are put under the mantle—feathers that are a part of the bird’s body. You can leave this out if you want to show off these amazing back muscles, but they can help make the wings look like a whole.

5. How to Draw Angel Wings

Step 1

The guide lines are finished—it’s time for the real drawing now! We’re going to do it in the exact opposite order to the way we drew the structure. First, draw the mantle and the tiny coverts. Keep them fluffy! There’s no need to draw the feathers separately, as they’re not normally visible that way.

Step 2

Draw the alula and the scapulars/tertials.

Step 3

Draw the lesser coverts. Here’s where you need to start paying attention to the order of the feathers. In the back, start drawing from the elbow side, and in the front from the finger side.

Step 4

Draw the greater coverts. Keep the order!

Step 5

Finally, the beautiful primaries and secondaries. You can draw the rachis quite thick in them, but it should get thinner towards the tip.

Step 6

Once you’re done, you can outline the feathers. Just be careful: if the lines are too strong, they can look too thick and hard (unless it’s the style you’re going for, in which case go ahead!).

Simply Divine!

Now you know how to draw angel wings and the wings of a winged human. If you want to learn more about drawing humans, I recommend these tutorials:

How To Draw Angel Wings

Want to make a collage of some other beautiful piece of artwork? How to draw angel wings will be an indispensable skill that will save you a lot of time.

It is a fantastic thing that today with all the available information, technology, and tools we can create virtually any kind of professionally-looking artwork at home, or make a hand-made book, etc.

I know for sure that once you have learned how to draw angel wings, you’ll be able to draw any type of angel wings or create your own original.

The variations are infinite and you are limited only by your fantasy.

If you have chance, look at the old masters paintings of angels, you’ll quickly find that the angel wings are often painted or drawn in different shapes and sizes.

Guardian angels, Archangels, or other Divine Authorities have large long feathered wings while other angels are illustrated as curly-haired children with small cute wings.

Angel of Love – Cupid is a very good example of that.

I am going to show you a basic procedure of how to draw angel wings. The following illustration is maybe one of the most common among angel wings drawing.

The point is to learn the drawing process, step-by-step so that you can make your own variations as you like. It is very simple and won’t take you more than a couple of minutes to complete it, once you learn this basic sequence.

This picture is a completed drawing of angel wings. Click on the picture to see it in its full size and observe how simple that really is. If necessary print it out.

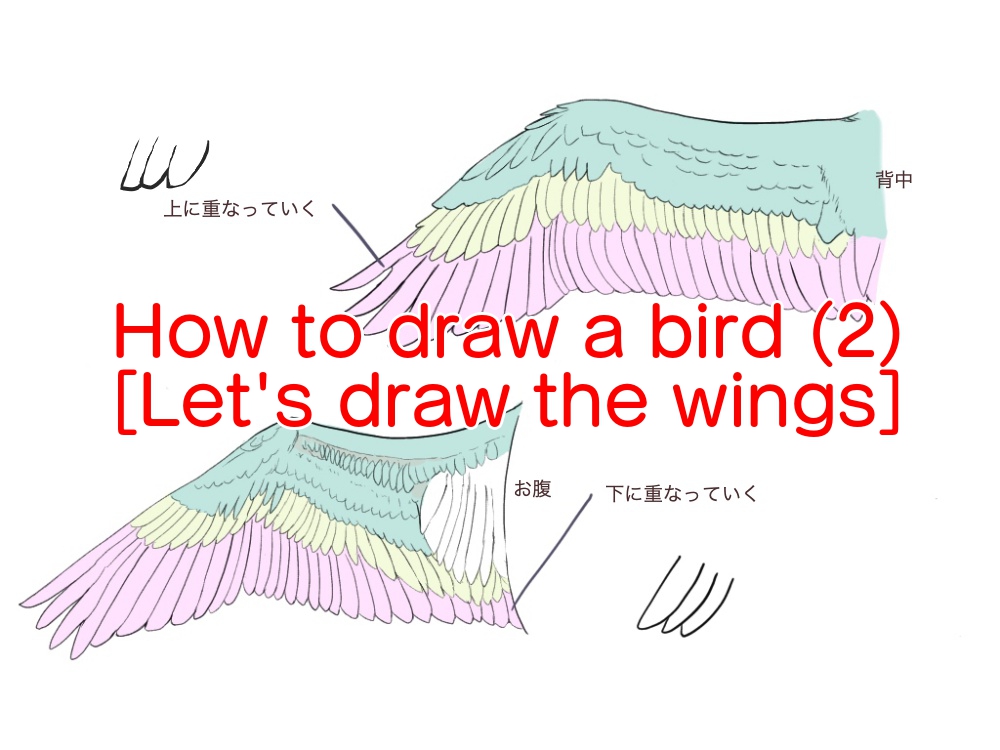

How to draw a bird (2) [Let’s draw the wings]

Birds such as sparrows and crows are usually seen in our daily lives.

Wings are indispensable when drawing these birds.

Wings are also necessary when drawing other characters such as angels, demons, and unicorns.

Birds are often seen in our daily lives, so some people may say that they can draw wings without much difficulty.

However, if you draw them casually, you may not be able to recognize the details, or if you change the direction or add movement, you may lose sight of them. ……

When you draw a wing, you need to be aware of its characteristics so that you can draw a wing that looks more like it.

In this section, we will introduce the characteristics of wings and points to keep in mind when drawing them.

If you want to draw a bird flapping in the sky, or an angel or a devil, please check it out.

1. Characteristics of wings and points to consider when drawing them

Let’s start by looking at the general structure of a bird’s wing.

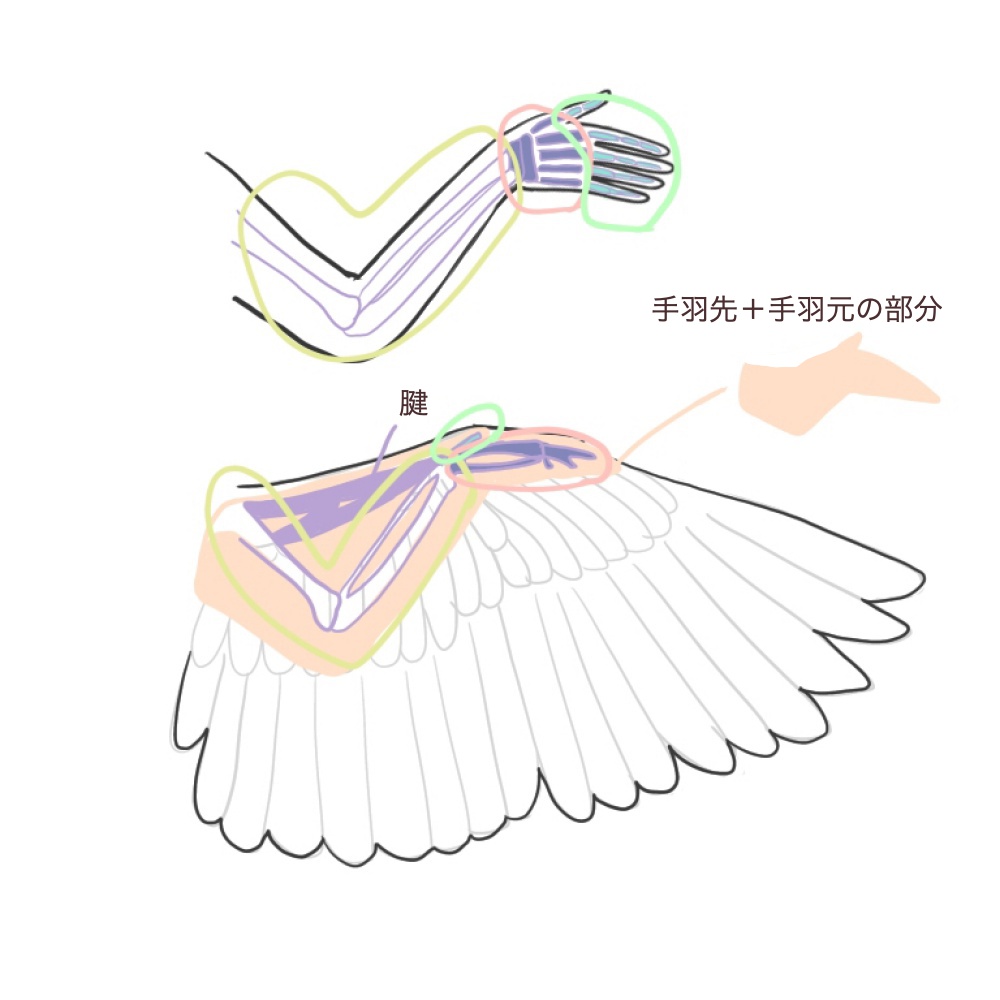

◆The skeleton of a wing

The skeleton of a wing is similar to that of a human from the arms to the fingertips.

In the illustration above, the area circled in the same color is the part of the skeleton that is similar in humans and birds.

The purple part of the wing extending from the arm to the wrist is the tendon.

Because of these tendons, the arm is not stretched out completely straight like in humans, but the bones are in an open V-shape.

When drawing wings, it is easier to draw these skeletons and skeletal parts (wing tips + wing base) as a rough sketch first, and then add the wings on top of them.

How to attach the wings

Now that you have a rough idea of the shape of the skeleton, it is time to add the wings.

Now, I will show you how to attach the wings.

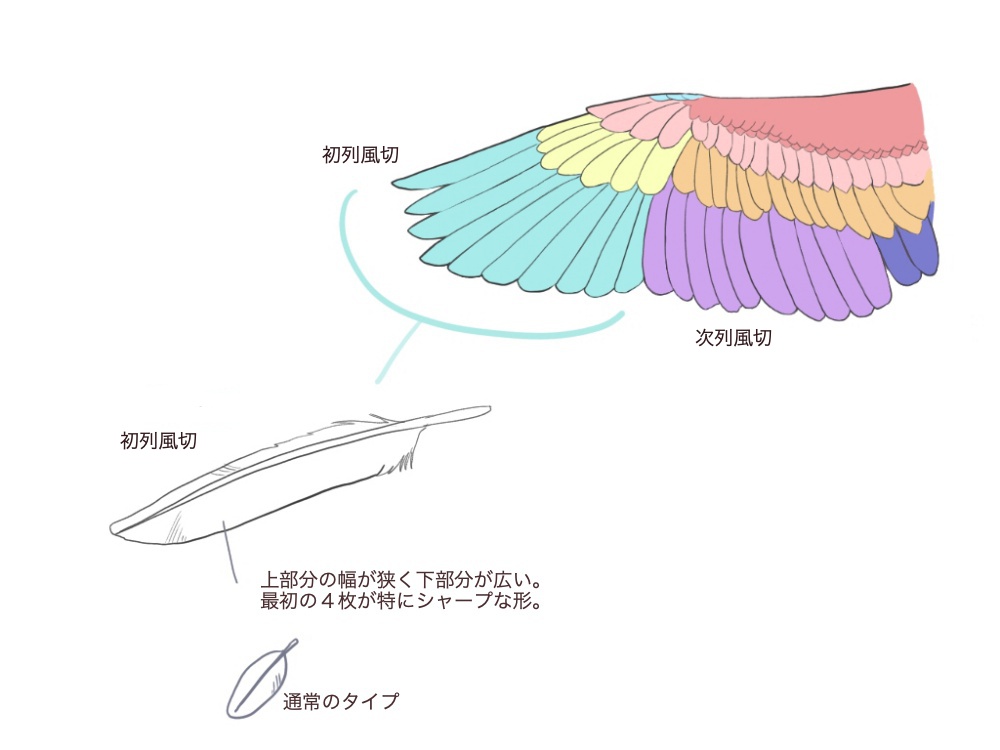

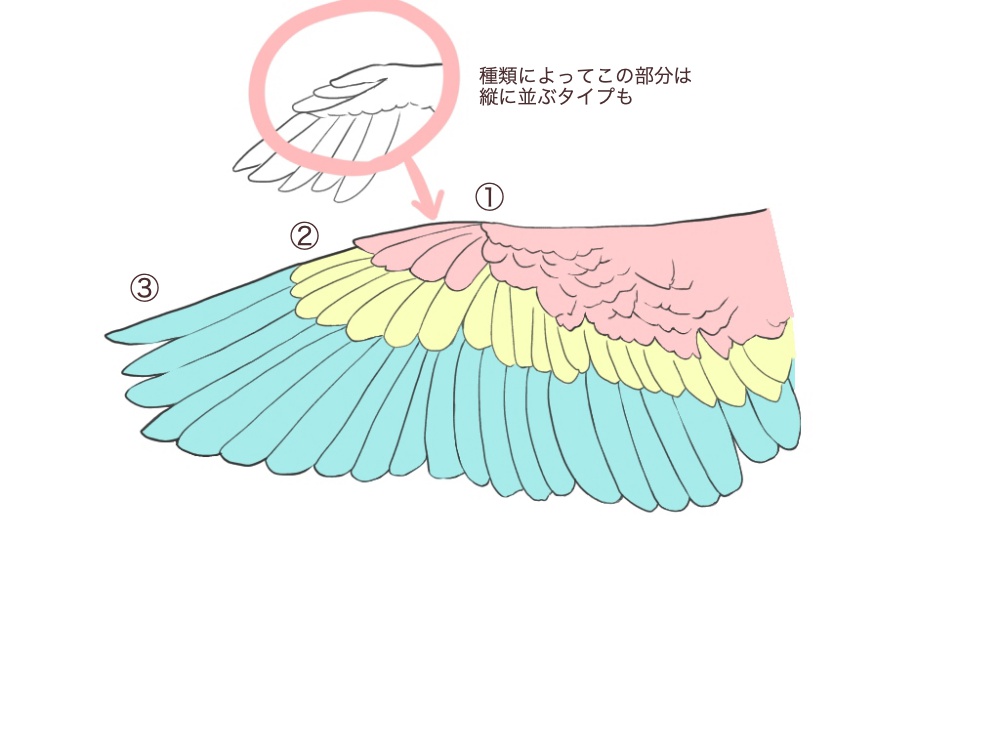

The feathers are divided into three major vertical sections.

It’s a good idea to start with these three sections in mind.

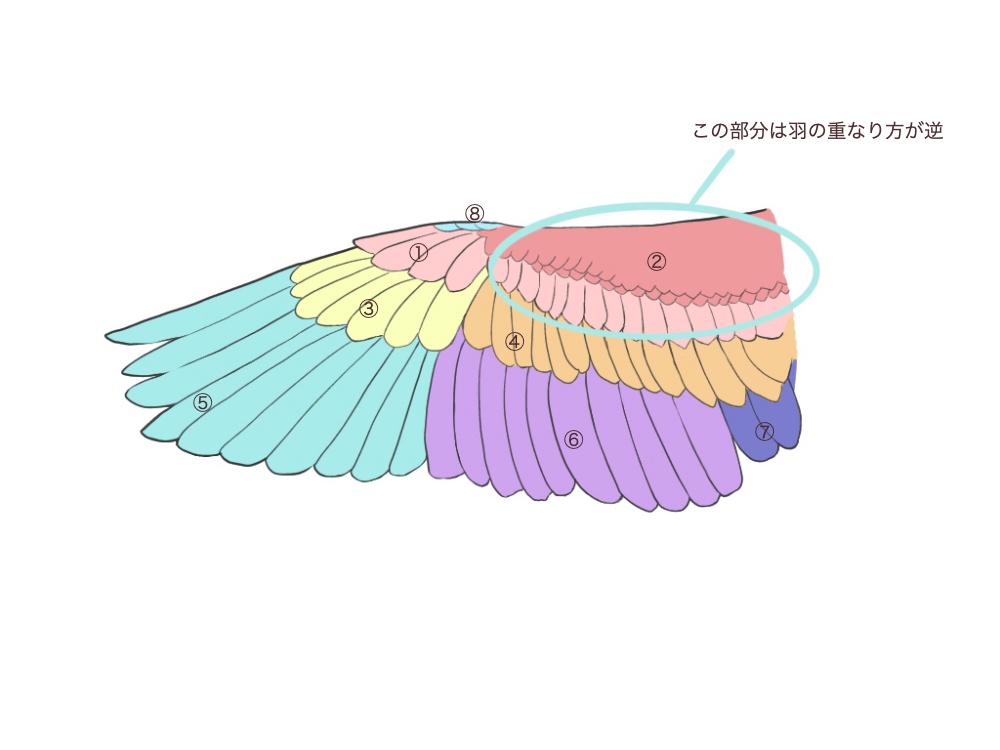

If you want to go into more detail, the feathers can be divided into eight parts in total.

When a bird flies, its “wind vane” is active.

When raising the wing, the wind vane cuts the wind to reduce air resistance, and when lowering the wing, it catches the wind and converts it into propulsive force.

When drawing a wing, it is a good idea to pay special attention to the shape of the wind vane.

The first row of windrows is longer and sharper with a slightly pointed tip.

In contrast, the next row of wind shears is slightly wider and more rounded in shape.

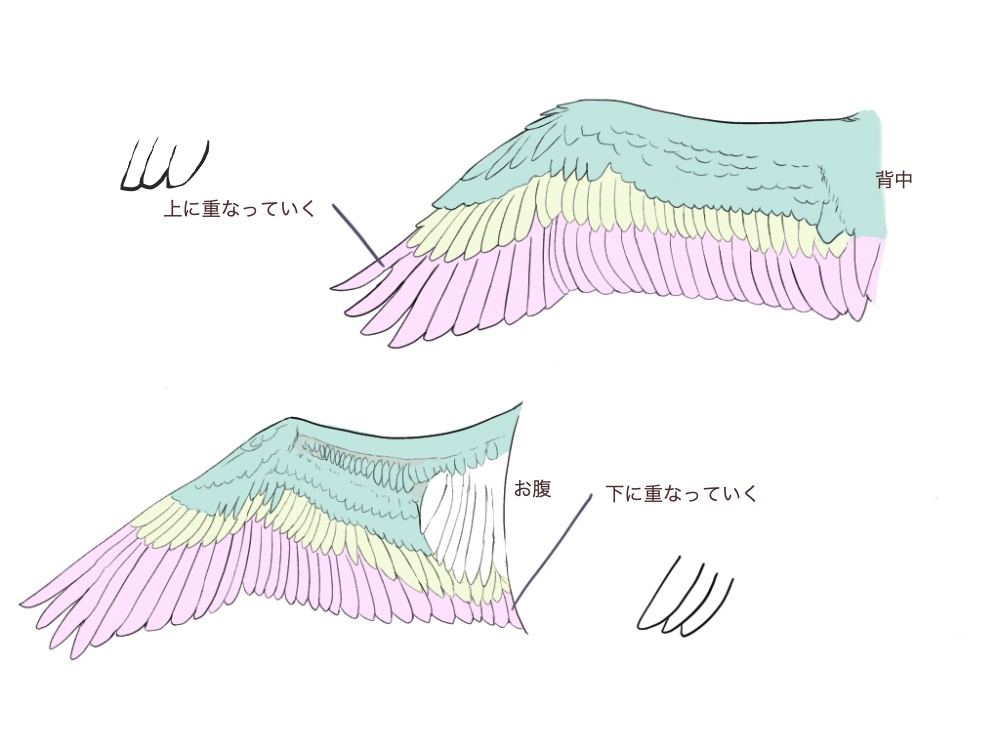

Also note that the wings are slightly different when viewed from the underside, as the feathers are attached in a different way.

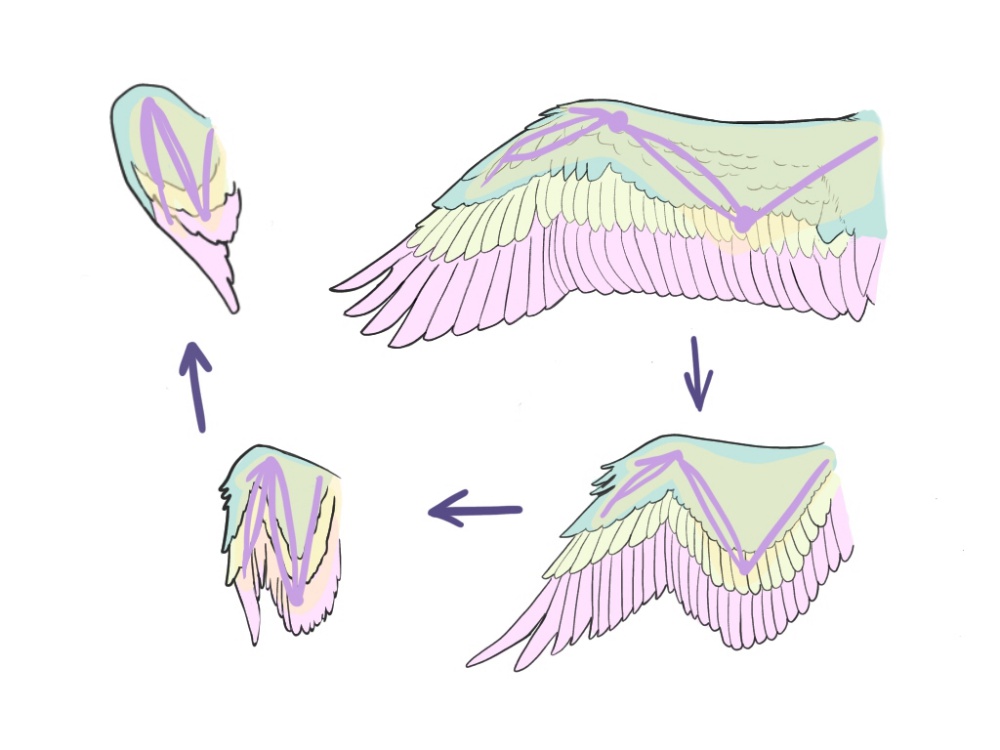

◆How to fold the wings

The wings of a bird are usually folded along the body.

In this case, the wing is folded with the arm bent and the part from the wrist to the fingertips bent downward.

In humans, it is like bending the elbow and pointing the back of the hand diagonally downward.

(If it is difficult to understand, it may be easier to grasp the shape by imagining a skeleton.

As you draw the arms in, pay attention to how the feathers on the arms and elbows come together, and draw the feathers in layers.

The upper half of the feathers will be almost completely hidden because it will be below the wrist.

The visible lower half of the wind feathers should be along the body towards the tail.

2. Characteristics of bat wings and points to consider when drawing them

Bats are a type of mammal, not a bird.

However, they have large wings like birds.

Bat wings are often used for demon characters and Halloween, so let’s check out some tips on how to draw them.

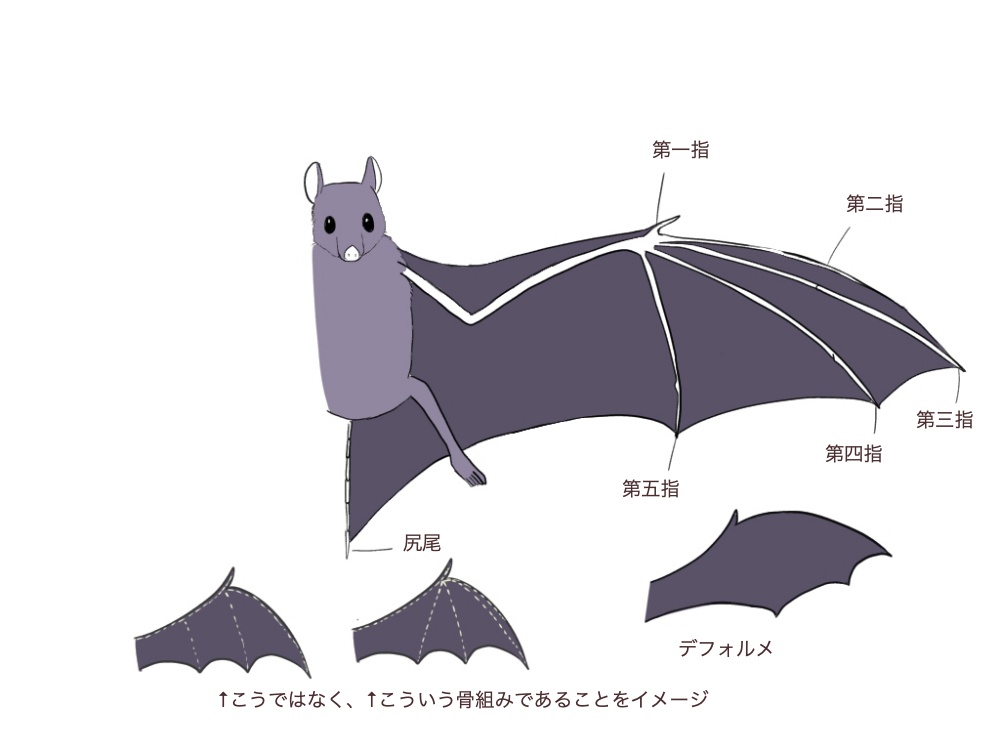

If you look at the skeleton of a bat’s wing, you can clearly see that bats have very long fingers.

The wings of bats are made of a thin membrane, not feathers.

The skin connects the long fingers with the bones of the arms, legs, and tail, like the sails of a sailboat.

The five fingers are the same as in humans: thumb, index, middle, ring, and little finger.

The thumb is outside the membrane, while the rest of the fingers are encased in the membrane.

When drawing the bones of the bat’s wings, be aware that they are fingers, and draw them in a radial pattern to make them look more like that.

Depending on the deformation and the design, I sometimes dare to draw a vertical line as in the picture on the left below.

\ We are accepting requests for articles on how to use /