How to open terminal in ubuntu

How to open terminal in ubuntu

How to Open Terminal in Ubuntu Linux

When you are absolutely new to Ubuntu, things could be overwhelming at the beginning. Even the simplest of the tasks like opening a terminal window in Ubuntu could seem complicated.

That’s okay. It’s nothing to be ashamed of. You are in a completely new environment and it could take some time to getting used to it.

Let’s focus on the terminal here and let me show a few ways to launch the terminal in Ubuntu.

Method 1: Launch Ubuntu terminal using keyboard shortcut

I find using keyboard shortcuts in Ubuntu a lot more convenient. To open a terminal, you can press Ctrl, Alt and T keys together.

It’s not that complicate. Press and hold Ctrl first and then press Alt key and hold on to it as well. When you are holding both Ctrl and Alt keys, press T and you’ll see that a new terminal window is opened.

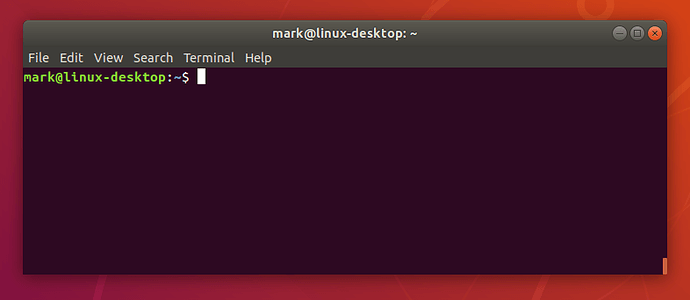

» data-medium-file=»https://itsfoss.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/terminal-window-ubuntu-300×154.png» data-large-file=»https://itsfoss.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/terminal-window-ubuntu.png» width=»799″ height=»409″ src=»https://itsfoss.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/terminal-window-ubuntu.png» alt=»terminal window ubuntu» data-lazy-srcset=»https://itsfoss.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/terminal-window-ubuntu.png 799w, https://itsfoss.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/terminal-window-ubuntu-300×154.png 300w, https://itsfoss.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/terminal-window-ubuntu-768×393.png 768w» data-lazy-sizes=»(max-width: 799px) 100vw, 799px» data-lazy-src=»https://itsfoss.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/terminal-window-ubuntu.png?is-pending-load=1″ srcset=»data:image/gif;base64,R0lGODlhAQABAIAAAAAAAP///yH5BAEAAAAALAAAAAABAAEAAAIBRAA7″> Terminal application in Window

That was easy, right? But I can understand that you may not remember the shortcut always, even thought it is really easy. In that case, the second method comes to your rescue.

Method 2: Open terminal from the menu

This is the generic method for opening any installed application in Ubuntu.

Press the Windows key (also known as super key in Linux) and type terminal. It will show the terminal application icon and you click on it to launch the terminal.

» data-medium-file=»https://itsfoss.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/launch-terminal-ubuntu-300×96.png» data-large-file=»https://itsfoss.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/launch-terminal-ubuntu.png» width=»797″ height=»256″ src=»https://itsfoss.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/launch-terminal-ubuntu.png» alt=»launch terminal ubuntu» data-lazy-srcset=»https://itsfoss.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/launch-terminal-ubuntu.png 797w, https://itsfoss.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/launch-terminal-ubuntu-300×96.png 300w, https://itsfoss.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/launch-terminal-ubuntu-768×247.png 768w» data-lazy-sizes=»(max-width: 797px) 100vw, 797px» data-lazy-src=»https://itsfoss.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/launch-terminal-ubuntu.png?is-pending-load=1″ srcset=»data:image/gif;base64,R0lGODlhAQABAIAAAAAAAP///yH5BAEAAAAALAAAAAABAAEAAAIBRAA7″> Launching terminal in Ubuntu from the menu

You can use this method to launch any other application. Just type the name of the application and it will show all the installed applications that match your searched term.

You cannot go wrong with this method.

Bonus Tip: Open current directory location in terminal from Nautilus

Did you know that you can open a particular location in terminal from the file explorer (called Nautilus)?

When you are in the file explorer, right click on an empty space. In the context menu, you’ll see the option of ‘Open in Terminal’.

» data-medium-file=»https://itsfoss.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/open-terminal-nautilus-300×146.png» data-large-file=»https://itsfoss.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/open-terminal-nautilus-800×388.png» width=»800″ height=»388″ src=»https://itsfoss.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/open-terminal-nautilus-800×388.png» alt=»open terminal nautilus» data-lazy-srcset=»https://itsfoss.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/open-terminal-nautilus-800×388.png 800w, https://itsfoss.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/open-terminal-nautilus-300×146.png 300w, https://itsfoss.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/open-terminal-nautilus-768×373.png 768w, https://itsfoss.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/open-terminal-nautilus.png 896w» data-lazy-sizes=»(max-width: 800px) 100vw, 800px» data-lazy-src=»https://itsfoss.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/open-terminal-nautilus-800×388.png?is-pending-load=1″ srcset=»data:image/gif;base64,R0lGODlhAQABAIAAAAAAAP///yH5BAEAAAAALAAAAAABAAEAAAIBRAA7″> Right click in the file explorer and select ‘Open in Terminal’

You click on this option and it will open a new terminal window with the same directory location you were in the file explorer.

» data-medium-file=»https://itsfoss.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/terminal-opened-from-nautilus-300×155.png» data-large-file=»https://itsfoss.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/terminal-opened-from-nautilus.png» width=»786″ height=»407″ src=»https://itsfoss.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/terminal-opened-from-nautilus.png» alt=»terminal opened from nautilus» data-lazy-srcset=»https://itsfoss.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/terminal-opened-from-nautilus.png 786w, https://itsfoss.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/terminal-opened-from-nautilus-300×155.png 300w, https://itsfoss.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/terminal-opened-from-nautilus-768×398.png 768w» data-lazy-sizes=»(max-width: 786px) 100vw, 786px» data-lazy-src=»https://itsfoss.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/terminal-opened-from-nautilus.png?is-pending-load=1″ srcset=»data:image/gif;base64,R0lGODlhAQABAIAAAAAAAP///yH5BAEAAAAALAAAAAABAAEAAAIBRAA7″> Opened terminal window in the same folder as it was in Nautilus

This saves some time when you are in a deep nested directory and have to edit something there in the terminal.

That’s cool. You learned not only to open terminal window in Ubuntu but you also learned to open terminal with specific directory from Nautilus. How cool is that?

Creator of It’s FOSS. An ardent Linux user & open source promoter. Huge fan of classic detective mysteries ranging from Agatha Christie and Sherlock Holmes to Detective Columbo & Ellery Queen. Also a movie buff with a soft corner for film noir.

What is a terminal and how do I open and use it?

5 Answers 5

What is it:

The terminal is an interface in which you can type and execute text based commands.

Why use it:

It can be much faster to complete some tasks using a Terminal than with graphical applications and menus. Another benefit is allowing access to many more commands and scripts.

A common terminal task of installing an application can be achieved within a single command, compared to navigating through the Software Centre or Synaptic Manager.

For example the following would install Deluge bittorrent client:

To save a detailed list of files in the current directory tree to a file called listing.txt :

Sometimes you will also see the following notation:

A similar notation is:

This means that the command should be run as root, that is, using sudo :

Note that the # character is also used for comments.

How do I open a terminal:

Open the Dash (Super Key) or Applications and type terminal

For older or Ubuntu versions: (More Info)

Applications → Accessories → Terminal

Alternative names for the terminal:

Common commands & Further information

A Terminal is your interface to the underlying operating system via a shell, usually bash. It is a command line.

Back in the day, a Terminal was a screen+keyboard that was connected to a server. Today, it is usally just a progam.

The terminal (also known as console) is an application in which you can execute commands directly. It looks like:

The Ubuntu wiki has an article about the terminal which includes information on starting the terminal in Xubuntu and Lubuntu, and a basic overview of commonly used commands. It’s recommended for reading as it includes much examples as well.

A Terminal is a command interpreter. A Terminal is an entity that takes input from the user and deals with the computer rather than the user deal directly with the computer. If the user had to deal directly with the computer he would not get much done as the computer only understands strings of 1’s and 0’s

Example

When a person drives a car, that person doesn’t have to actually adjust every detail that goes along with making the engine run, or the electronic system controlling all of the engine timing and so on. The dashboard would also be considered part of the the Terminal since pertinent (Having logical precise relevance to the matter at hand) information relating to the user’s involvement in operating the car is displayed there. In fact any part of the car that the user has control of during operation of the car would be considered part of the Terminal.

Terminal is a program that allows the user to use the computer without him having to deal directly with it. It is in a sense a protective shell that prevents the user and computer from coming into contact with one another.

Запуск терминала в Ubuntu

В сегодняшней статье мы поговорим о том, как открыть терминал в Ubuntu Linux с помощью различных способов, начиная горячими клавишами и заканчивая графическим интерфейсом. Хотя статья ориентирована на Ubuntu, большинство способов будут работать и в других дистрибутивах.

Как открыть терминал в Ubuntu

1. Горячие клавиши Ctrl+Alt+T

Это особенность дистрибутива Ubuntu, вы можете открыть терминал Linux в любом графическом окружении, просто нажав сочетание клавиш Ctrl+Alt+T одновременно:

Далее вы можете задать комбинацию из трёх клавиш.

2. Всплывающее окно «выполнить»

Почти во всех окружениях при нажатии сочетания клавиш Alt+F2 открывается строка ввода, из которой уже можно выполнять команды и запускать программы:

Но вывод команды здесь вы не сможете увидеть, поэтому надо запустить полноценный терминал. В Gnome это gnome-terminal:

В других окружениях рабочего стола команда может отличаться. Если вы не знаете, какая команда используется в вашей системе, смотрите следующий способ.

3. Главное меню системы

В главном меню дистрибутива собраны все установленные программы. Сначала нажмите клавишу Windows (Super), чтобы открыть главное меню. В том числе там есть и терминал. В окружении Gnome вы можете набрать начало имени программы, например «терм» или «term», и система отобразит доступные для запуска программы.

Просто выберите в списке нужную программу, чтобы запустить терминал Linux. Если же поиска в вашем меню нет, то терминал следует искать в категории Системные или Утилиты:

4. Системные терминалы

По умолчанию в любом дистрибутиве Linux открыто 12 системных терминалов. Вы можете использовать один из них. Вернее, вам доступно только 11, потому что в одном уже открыто ваше графическое окружение, в котором вы работаете. Обычно, это первый или седьмой терминал. Это не совсем запуск терминала Ubuntu, так как эти терминалы уже запущены.

Для переключения между этими терминалами используется комбинация клавиш Ctrl+Alt+F и номер терминала. Например, Ctrl+Alt+F2 или Ctrl+Alt+F3. После нажатия этого сочетания графическое окружение исчезнет, а вместо него появится черный экран с предложением ввода логина и пароля:

Если вы введёте правильные данные для аутентификации, откроется терминал Linux.

5. Открыть терминал в папке

Если у вас запущен файловый менеджер Nautilus, и вы хотите открыть терминал Linux в текущей папке, то сделать это очень просто. Откройте контекстное меню и выберите открыть в терминале:

Выводы

5 Ways to Open a Terminal in Ubuntu

Why would one want to use a command-line in Linux? Get to know the reasons and also the ways you can launch the Terminal on your Ubuntu PC. You can use keyboard shortcuts as well as a few GUI ways, as described in this guide.

E ven though Ubuntu supports many applications with amazing Graphical User Interfaces (GUI), there are always reasons why users prefer using the Terminal to perform different tasks.

Here are several reasons why you might need to use the Ubuntu command-line.

Reasons to use command-line on Linux

Ways to open a Terminal on Ubuntu

We will show five ways that you can use to launch the Terminal and carry out your tasks easily. Our Ubuntu release of choice in this tutorial is Ubuntu 20.04 LTS recently released.

1. Opening the Terminal using Ctrl + Alt + T

Even for new Ubuntu users, this keyboard shortcut is not new. Hold on the Ctrl and Alt key then press T once. This combination will open the Terminal on the ‘Home’ directory.

2. Launching the Terminal using the Run command

It is also a quick method that you can use to open the Terminal and even other applications. Using the keyboard, enter the combination, Alt + F2. It will open a dialog box. Enter the word ‘gnome-terminal‘ and hit Enter.

This method is more useful in situations where your GUI system is not responding, and you cannot even move the cursor. You can open the Terminal and kill the troublesome applications from here.

3. Search and Open the Terminal using the Ubuntu Dash

Ubuntu Dash gives you quick access to installed applications by searching the name of the particular app. On Ubuntu, you can easily access the Dash by clicking on the ‘Show Applications‘ icon on the bottom left corner or just by pressing the ‘Windows‘ key. Type the word ‘Terminal‘ at the search box at the top.

4. Right-clicking on the Desktop or inside a directory

Another quick and straightforward way to open the Terminal is by right-clicking anywhere on the empty Desktop and choosing the option, ‘Open in Terminal.’

Additionally, you can do the same even inside a directory. Right-click anywhere in the folder and select the option ‘Open in Terminal.‘

5. Open the Virtual Terminal using Ctrl + Alt + Function Key.

In the methods we have discussed above, we are opening the Terminal in our Ubuntu Graphical User Interface. There are situations where you might need to switch from using the native GUI to a console.

This method is suitable when you are playing around with graphic drivers, or your GUI has frozen, and you want to kill specific processes.

To switch to console, use the keyboard combination Ctrl + Alt + F3. You will be required to login with your credentials to start a session. See the image below.

To switch back to the Graphical User Interface (GUI), use the keyboard combination Ctrl +Alt + F2. If this combination does not work for your PC, you can try using other Function Keys like F4.

Conclusion

Those were the five methods you can use to open your Ubuntu Terminal easy and fast. Check Ten basic Linux commands to learn for every Beginner if you are trying out Ubuntu for the first time.

How to open terminal in ubuntu

Your submission was sent successfully! Close

1. Overview

The Linux command line is a text interface to your computer. Often referred to as the shell, terminal, console, prompt or various other names, it can give the appearance of being complex and confusing to use. Yet the ability to copy and paste commands from a website, combined with the power and flexibility the command line offers, means that using it may be essential when trying to follow instructions online, including many on this very website!

This tutorial will teach you a little of the history of the command line, then walk you through some practical exercises to become familiar with a few basic commands and concepts. We’ll assume no prior knowledge, but by the end we hope you’ll feel a bit more comfortable the next time you’re faced with some instructions that begin “Open a terminal”.

What you’ll learn

What you’ll need

Every Linux system includes a command line of one sort or another. This tutorial includes some specfic steps for Ubuntu 18.04 but most of the content should work regardless of your Linux distribution.

2. A brief history lesson

During the formative years of the computer industry, one of the early operating systems was called Unix. It was designed to run as a multi-user system on mainframe computers, with users connecting to it remotely via individual terminals. These terminals were pretty basic by modern standards: just a keyboard and screen, with no power to run programs locally. Instead they would just send keystrokes to the server and display any data they received on the screen. There was no mouse, no fancy graphics, not even any choice of colour. Everything was sent as text, and received as text. Obviously, therefore, any programs that ran on the mainframe had to produce text as an output and accept text as an input.

Compared with graphics, text is very light on resources. Even on machines from the 1970s, running hundreds of terminals across glacially slow network connections (by today’s standards), users were still able to interact with programs quickly and efficiently. The commands were also kept very terse to reduce the number of keystrokes needed, speeding up people’s use of the terminal even more. This speed and efficiency is one reason why this text interface is still widely used today.

When logged into a Unix mainframe via a terminal users still had to manage the sort of file management tasks that you might now perform with a mouse and a couple of windows. Whether creating files, renaming them, putting them into subdirectories or moving them around on disk, users in the 70s could do everything entirely with a textual interface.

Linux is a sort-of-descendent of Unix. The core part of Linux is designed to behave similarly to a Unix system, such that most of the old shells and other text-based programs run on it quite happily. In theory you could even hook up one of those old 1970s terminals to a modern Linux box, and access the shell through that. But these days it’s far more common to use a software terminal: that same old Unix-style text interface, but running in a window alongside your graphical programs. Let’s see how you can do that yourself!

3. Opening a terminal

On a Ubuntu 18.04 system you can find a launcher for the terminal by clicking on the Activities item at the top left of the screen, then typing the first few letters of “terminal”, “command”, “prompt” or “shell”. Yes, the developers have set up the launcher with all the most common synonyms, so you should have no problems finding it.

Other versions of Linux, or other flavours of Ubuntu, will usually have a terminal launcher located in the same place as your other application launchers. It might be hidden away in a submenu or you might have to search for it from within your launcher, but it’s likely to be there somewhere.

If you can’t find a launcher, or if you just want a faster way to bring up the terminal, most Linux systems use the same default keyboard shortcut to start it: Ctrl-Alt-T.

However you launch your terminal, you should end up with a rather dull looking window with an odd bit of text at the top, much like the image below. Depending on your Linux system the colours may not be the same, and the text will likely say something different, but the general layout of a window with a large (mostly empty) text area should be similar.

Let’s run our first command. Click the mouse into the window to make sure that’s where your keystrokes will go, then type the following command, all in lower case, before pressing the Enter or Return key to run it.

You should see a directory path printed out (probably something like /home/YOUR_USERNAME ), then another copy of that odd bit of text.

There are a couple of basics to understand here, before we get into the detail of what the command actually did. First is that when you type a command it appears on the same line as the odd text. That text is there to tell you the computer is ready to accept a command, it’s the computer’s way of prompting you. In fact it’s usually referred to as the prompt, and you might sometimes see instructions that say “bring up a prompt”, “open a command prompt”, “at the bash prompt” or similar. They’re all just different ways of asking you to open a terminal to get to a shell.

On the subject of synonyms, another way of looking at the prompt is to say that there’s a line in the terminal into which you type commands. A command line, if you will. Again, if you see mention of “command line”, including in the title of this very tutorial, it’s just another way of talking about a shell running in a terminal.

The second thing to understand is that when you run a command any output it produces will usually be printed directly in the terminal, then you’ll be shown another prompt once it’s finished. Some commands can output a lot of text, others will operate silently and won’t output anything at all. Don’t be alarmed if you run a command and another prompt immediately appears, as that usually means the command succeeded. If you think back to the slow network connections of our 1970s terminals, those early programmers decided that if everything went okay they may as well save a few precious bytes of data transfer by not saying anything at all.

The importance of case

Be extra careful with case when typing in the command line. Typing PWD instead of pwd will produce an error, but sometimes the wrong case can result in a command appearing to run, but not doing what you expected. We’ll look at case a little more on the next page but, for now, just make sure to type all the following lines in exactly the case that’s shown.

A sense of location

Now to the command itself. pwd is an abbreviation of ‘print working directory’. All it does is print out the shell’s current working directory. But what’s a working directory?

One important concept to understand is that the shell has a notion of a default location in which any file operations will take place. This is its working directory. If you try to create new files or directories, view existing files, or even delete them, the shell will assume you’re looking for them in the current working directory unless you take steps to specify otherwise. So it’s quite important to keep an idea of what directory the shell is “in” at any given time, after all, deleting files from the wrong directory could be disastrous. If you’re ever in any doubt, the pwd command will tell you exactly what the current working directory is.

You can change the working directory using the cd command, an abbreviation for ‘change directory’. Try typing the following:

Note that the directory separator is a forward slash («/»), not the backslash that you may be used to from Windows or DOS systems

Now your working directory is “/”. If you’re coming from a Windows background you’re probably used to each drive having its own letter, with your main hard drive typically being “C:”. Unix-like systems don’t split up the drives like that. Instead they have a single unified file system, and individual drives can be attached (“mounted”) to whatever location in the file system makes most sense. The “/” directory, often referred to as the root directory, is the base of that unified file system. From there everything else branches out to form a tree of directories and subdirectories.

Too many roots

Beware: although the “/” directory is sometimes referred to as the root directory, the word “root” has another meaning. root is also the name that has been used for the superuser since the early days of Unix. The superuser, as the name suggests, has more powers than a normal user, so can easily wreak havoc with a badly typed command. We’ll look at the superuser account more in section 7. For now you only have to know that the word “root” has multiple meanings in the Linux world, so context is important.

From the root directory, the following command will move you into the “home” directory (which is an immediate subdirectory of “/”):

Typing cd on its own is a quick shortcut to get back to your home directory:

Notice that in the previous example we described a route to take through the directories. The path we used means “starting from the working directory, move to the parent / from that new location move to the parent again”. So if we wanted to go straight from our home directory to the “etc” directory (which is directly inside the root of the file system), we could use this approach:

Relative and absolute paths

Most of the examples we’ve looked at so far use relative paths. That is, the place you end up at depends on your current working directory. Consider trying to cd into the “etc” folder. If you’re already in the root directory that will work fine:

But what if you’re in your home directory?

But we have seen two commands that are absolute. No matter what your current working directory is, they’ll have the same effect. The first is when you run cd on its own to go straight to your home directory. The second is when you used cd / to switch to the root directory. In fact any path that starts with a forward slash is an absolute path. You can think of it as saying “switch to the root directory, then follow the route from there”. That gives us a much easier way to switch to the etc directory, no matter where we currently are in the file system:

It also gives us another way to get back to your home directory, and even to the folders within it. Suppose you want to go straight to your “Desktop” folder from anywhere on the disk (note the upper-case “D”). In the following command you’ll need to replace USERNAME with your own username, the whoami command will remind you of your username, in case you’re not sure:

There’s one other handy shortcut which works as an absolute path. As you’ve seen, using “/” at the start of your path means “starting from the root directory”. Using the tilde character («

«) at the start of your path similarly means “starting from my home directory”.

Now that odd text in the prompt might make a bit of sense. Have you noticed it changing as you move around the file system? On a Ubuntu system it shows your username, your computer’s network name and the current working directory. But if you’re somewhere inside your home directory, it will use “

” as an abbreviation. Let’s wander around the file system a little, and keep an eye on the prompt as you do so:

You must be bored with just moving around the file system by now, but a good understanding of absolute and relative paths will be invaluable as we move on to create some new folders and files!

4. Creating folders and files

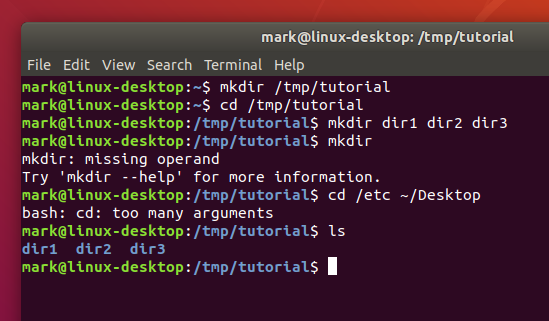

In this section we’re going to create some real files to work with. To avoid accidentally trampling over any of your real files, we’re going to start by creating a new directory, well away from your home folder, which will serve as a safer environment in which to experiment:

Notice the use of an absolute path, to make sure that we create the tutorial directory inside /tmp. Without the forward slash at the start the mkdir command would try to find a tmp directory inside the current working directory, then try to create a tutorial directory inside that. If it couldn’t find a tmp directory the command would fail.

In case you hadn’t guessed, mkdir is short for ‘make directory’. Now that we’re safely inside our test area (double check with pwd if you’re not certain), let’s create a few subdirectories:

/Desktop ). But this time we’ve added three things after the mkdir command. Those things are referred to as parameters or arguments, and different commands can accept different numbers of arguments. The mkdir command expects at least one argument, whereas the cd command can work with zero or one, but no more. See what happens when you try to pass the wrong number of parameters to a command:

Back to our new directories. The command above will have created three new subdirectories inside our folder. Let’s take a look at them with the ls (list) command:

If you’ve followed the last few commands, your terminal should be looking something like this:

Notice that mkdir created all the folders in one directory. It didn’t create dir3 inside dir2 inside dir1, or any other nested structure. But sometimes it’s handy to be able to do exactly that, and mkdir does have a way:

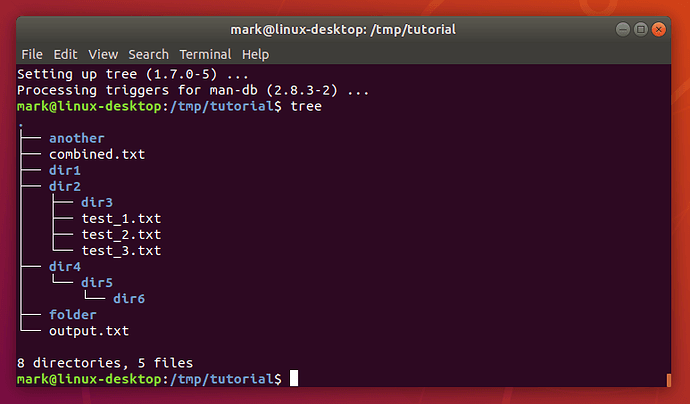

This time you’ll see that only dir4 has been added to the list, because dir5 is inside it, and dir6 is inside that. Later we’ll install a useful tool to visualise the structure, but you’ve already got enough knowledge to confirm it:

The “-p” that we used is called an option or a switch (in this case it means “create the parent directories, too”). Options are used to modify the way in which a command operates, allowing a single command to behave in a variety of different ways. Unfortunately, due to quirks of history and human nature, options can take different forms in different commands. You’ll often see them as single characters preceded by a hyphen (as in this case), or as longer words preceded by two hyphens. The single character form allows for multiple options to be combined, though not all commands will accept that. And to confuse matters further, some commands don’t clearly identify their options at all, whether or not something is an option is dictated purely by the order of the arguments! You don’t need to worry about all the possibilities, just know that options exist and they can take several different forms. For example the following all mean exactly the same thing:

Now we know how to create multiple directories just by passing them as separare arguments to the mkdir command. But suppose we want to create a directory with a space in the name? Let’s give it a go:

You probably didn’t even need to type that one in to guess what would happen: two new folders, one called another and the other called folder. If you want to work with spaces in directory or file names, you need to escape them. Don’t worry, nobody’s breaking out of prison; escaping is a computing term that refers to using special codes to tell the computer to treat particular characters differently to normal. Enter the following commands to try out different ways to create folders with spaces in the name:

Although the command line can be used to work with files and folders with spaces in their names, the need to escape them with quote marks or backslashes makes things a little more difficult. You can often tell a person who uses the command line a lot just from their file names: they’ll tend to stick to letters and numbers, and use underscores («_») or hyphens («-«) instead of spaces.

Creating files using redirection

Our demonstration folder is starting to look rather full of directories, but is somewhat lacking in files. Let’s remedy that by redirecting the output from a command so that, instead of being printed to the screen, it ends up in a new file. First, remind yourself what the ls command is currently showing:

Suppose we wanted to capture the output of that command as a text file that we can look at or manipulate further. All we need to do is to add the greater-than character («>») to the end of our command line, followed by the name of the file to write to:

This time there’s nothing printed to the screen, because the output is being redirected to our file instead. If you just run ls on its own you should see that the output.txt file has been created. We can use the cat command to look at its content:

Okay, so it’s not exactly what was displayed on the screen previously, but it contains all the same data, and it’s in a more useful format for further processing. Let’s look at another command, echo :

Yes, echo just prints its arguments back out again (hence the name). But combine it with a redirect, and you’ve got a way to easily create small test files:

Where you want to pass multiple file names to a single command, there are some useful shortcuts that can save you a lot of typing if the files have similar names. A question mark («?») can be used to indicate “any single character” within the file name. An asterisk («*») can be used to indicate “zero or more characters”. These are sometimes referred to as “wildcard” characters. A couple of examples might help, the following commands all do the same thing:

What do you think will happen if we run those two commands a second time? Will the computer complain, because the file already exists? Will it append the text to the file, so it contains two copies? Or will it replace it entirely? Give it a try to see what happens, but to avoid typing the commands again you can use the Up Arrow and Down Arrow keys to move back and forth through the history of commands you’ve used. Press the Up Arrow a couple of times to get to the first cat and press Enter to run it, then do the same again to get to the second.

As you can see, the file looks the same. That’s not because it’s been left untouched, but because the shell clears out all the content of the file before it writes the output of your cat command into it. Because of this, you should be extra careful when using redirection to make sure that you don’t accidentally overwrite a file you need. If you do want to append to, rather than replace, the content of the files, double up on the greater-than character:

When viewing a file through less you can use the Up Arrow, Down Arrow, Page Up, Page Down, Home and End keys to move through your file. Give them a try to see the difference between them. When you’ve finished viewing your file, press q to quit less and return to the command line.

A note about case

Unix systems are case-sensitive, that is, they consider “A.txt” and “a.txt” to be two different files. If you were to run the following lines you would end up with three files:

Generally you should try to avoid creating files and folders whose name only varies by case. Not only will it help to avoid confusion, but it will also prevent problems when working with different operating systems. Windows, for example, is case-insensitive, so it would treat all three of the file names above as being a single file, potentially causing data loss or other problems.

You might be tempted to just hit the Caps Lock key and use upper case for all your file names. But the vast majority of shell commands are lower case, so you would end up frequently having to turn it on and off as you type. Most seasoned command line users tend to stick primarily to lower case names for their files and directories so that they rarely have to worry about file name clashes, or which case to use for each letter in the name.

Good naming practice

When you consider both case sensitivity and escaping, a good rule of thumb is to keep your file names all lower case, with only letters, numbers, underscores and hyphens. For files there’s usually also a dot and a few characters on the end to indicate the type of file it is (referred to as the “file extension”). This guideline may seem restrictive, but if you end up using the command line with any frequency you’ll be glad you stuck to this pattern.

5. Moving and manipulating files

Now that we’ve got a few files, let’s look at the sort of day-to-day tasks you might need to perform on them. In practice you’ll still most likely use a graphical program when you want to move, rename or delete one or two files, but knowing how to do this using the command line can be useful for bulk changes, or when the files are spread amongst different folders. Plus, you’ll learn a few more things about the command line along the way.

Let’s begin by putting our combined.txt file into our dir1 directory, using the mv (move) command:

The mv command also lets us move more than one file at a time. If you pass more than two arguments, the last one is taken to be the destination directory and the others are considered to be files (or directories) to move. Let’s use a single command to move combined.txt, all our test_n.txt files and dir3 into dir2. There’s a bit more going on here, but if you look at each argument at a time you should be able to work out what’s happening:

With combined.txt now moved into dir2, what happens if we decide it’s in the wrong place again? Instead of dir2 it should have been put in dir6, which is the one that’s inside dir5, which is in dir4. With what we now know about paths, that’s no problem either:

Notice how our mv command let us move the file from one directory into another, even though our working directory is something completely different. This is a powerful property of the command line: no matter where in the file system you are, it’s still possible to operate on files and folders in totally different locations.

Since we seem to be using (and moving) that file a lot, perhaps we should keep a copy of it in our working directory. Much as the mv command moves files, so the cp command copies them (again, note the space before the dot):

Great! Now let’s create another copy of the file, in our working directory but with a different name. We can use the cp command again, but instead of giving it a directory path as the last argument, we’ll give it a new file name instead:

That’s good, but perhaps the choice of backup name could be better. Why not rename it so that it will always appear next to the original file in a sorted list. The traditional Unix command line handles a rename as though you’re moving the file from one name to another, so our old friend mv is the command to use. In this case you just specify two arguments: the file you want to rename, and the new name you wish to use.

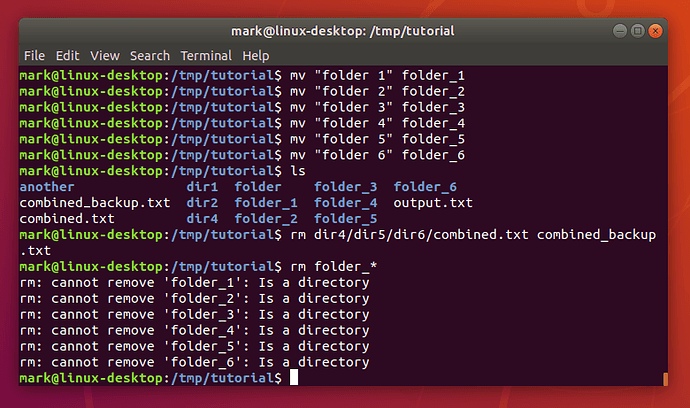

This also works on directories, giving us a way to sort out those difficult ones with spaces in the name that we created earlier. To avoid re-typing each command after the first, use the Up Arrow to pull up the previous command in the history. You can then edit the command before you run it by moving the cursor left and right with the arrow keys, and removing the character to the left with Backspace or the one the cursor is on with Delete. Finally, type the new character in place, and press Enter or Return to run the command once you’re finished. Make sure you change both appearances of the number in each of these lines.

Deleting files and folders

Warning

In this next section we’re going to start deleting files and folders. To make absolutely certain that you don’t accidentally delete anything in your home folder, use the pwd command to double-check that you’re still in the /tmp/tutorial directory before proceeding.

Now we know how to move, copy and rename files and directories. Given that these are just test files, however, perhaps we don’t really need three different copies of combined.txt after all. Let’s tidy up a bit, using the rm (remove) command:

Perhaps we should remove some of those excess directories as well:

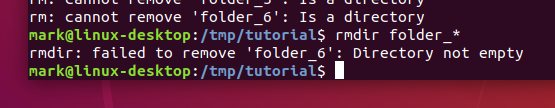

What happened there? Well, it turns out that rm does have one little safety net. Sure, you can use it to delete every single file in a directory with a single command, accidentally wiping out thousands of files in an instant, with no means to recover them. But it won’t let you delete a directory. I suppose that does help prevent you accidentally deleting thousands more files, but it does seem a little petty for such a destructive command to balk at removing an empty directory. Luckily there’s an rmdir (remove directory) command that will do the job for us instead:

Well that’s a little better, but there’s still an error. If you run ls you’ll see that most of the folders have gone, but folder_6 is still hanging around. As you may recall, folder_6 still has a folder 7 inside it, and rmdir will only delete empty folders. Again, it’s a small safety net to prevent you from accidentally deleting a folder full of files when you didn’t mean to.

6. A bit of plumbing

Today’s computers and phones have the sort of graphical and audio capabilities that our 70s terminal users couldn’t even begin to imagine. Yet still text prevails as a means to organise and categorise files. Whether it’s the file name itself, GPS coordintates embedded in photos you take on your phone, or the metadata stored in an audio file, text still plays a vital role in every aspect of computing. It’s fortunate for us that the Linux command line includes some powerful tools for manipulating text content, and ways to join those tools together to create something more capable still.

Similarly, if you wanted to know how many files and folders are in your home directory, and then tidy up after yourself, you could do this:

That method works, but creating a temporary file to hold the output from ls only to delete it two lines later seems a little excessive. Fortunately the Unix command line provides a shortcut that avoids you having to create a temporary file, by taking the output from one command (referred to as standard output or STDOUT) and feeding it directly in as the input to another command (standard input or STDIN). It’s as though you’ve connected a pipe between one command’s output and the next command’s input, so much so that this process is actually referred to as piping the data from one command to another. Here’s how to pipe the output of our ls command into wc :

Notice that there’s no temporary file created, and no file name needed. Pipes operate entirely in memory, and most Unix command line tools will expect to receive input from a pipe if you don’t specify a file for them to work on. Looking at the line above, you can see that it’s two commands, ls

Note that the spaces around the pipe character aren’t important, we’ve used them for clarity, but the following command works just as well, this time for telling us how many items are in the /etc directory:

Phew! That’s quite a few files. If we wanted to list them all it would clearly fill up more than a single screen. As we discovered earlier, when a command produces a lot of output, it’s better to use less to view it, and that advice still applies when using a pipe (remember, press q to quit):

That line probably resulted in a count that’s pretty close to the total number of lines in the file, if not exactly the same. Surely that can’t be right? Lop off the last pipe to see the output of the command for a better idea of what’s happening. If your file is very long, you might want to pipe it through less to make it easier to inspect:

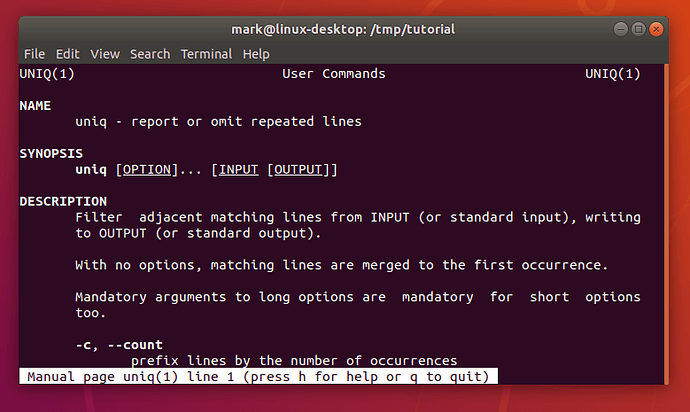

Because this type of documentation is accessed via the man command, you’ll hear it referred to as a “man page”, as in “check the man page for more details”. The format of man pages is often terse, think of them more as a quick overview of a command than a full tutorial. They’re often highly technical, but you can usually skip most of the content and just look for the details of the option or argument you’re using.

The uniq man page is a typical example in that it starts with a brief one-line description of the command, moves on to a synopsis of how to use it, then has a detailed description of each option or parameter. But whilst man pages are invaluable, they can also be inpenetrable. They’re best used when you need a reminder of a particular switch or parameter, rather than as a general resource for learning how to use the command line. Nevertheless, the first line of the DESCRIPTION section for man uniq does answer the question as to why duplicate lines haven’t been removed: it only works on adjacent matching lines.

The question, then, is how to rearrange the lines in our file so that duplicate entries are on adjacent lines. If we were to sort the contents of the file alphabetically, that would do the trick. Unix offers a sort command to do exactly that. A quick check of man sort shows that we can pass a file name directly to the command, so let’s see what it does to our file:

As you can see, the ability to pipe data from one command to another, building up long chains to manipulate your data, is a powerful tool, as well as reducing the need for temporary files, and saving you a lot of typing. For this reason you’ll see it used quite often in command lines. A long chain of commands might look intimidating at first, but remember that you can break even the longest chain down into individual commands (and look at their man pages) to get a better understanding of what it’s doing.

7. The command line and the superuser

One good reason for learning some command line basics is that instructions online will often favour the use of shell commands over a graphical interface. Where those instructions require changes to your machine that go beyond modifying a few files in your home directory, you’ll inevitably be faced with commands that need to be run as the machine’s administrator (or superuser in Unix parlance). Before you start running arbitrary commands you find in some dark corner of the internet, it’s worth understanding the implications of running as an administrator, and how to spot those instructions that require it, so you can better gauge whether they’re safe to run or not.

The superuser is, as the name suggests, a user with super powers. In older systems it was a real user, with a real username (almost always “root”) that you could log in as if you had the password. As for those super powers: root can modify or delete any file in any directory on the system, regardless of who owns them; root can rewrite firewall rules or start network services that could potentially open the machine up to an attack; root can shutdown the machine even if other people are still using it. In short, root can do just about anything, skipping easily round the safeguards that are usually put in place to stop users from overstepping their bounds.

Of course a person logged in as root is just as capable of making mistakes as anyone else. The annals of computing history are filled with tales of a mistyped command deleting the entire file system or killing a vital server. Then there’s the possibility of a malicious attack: if a user is logged in as root and leaves their desk then it’s not too tricky for a disgruntled colleague to hop on their machine and wreak havoc. Despite that, human nature being what it is, many administrators over the years have been guilty of using root as their main, or only, account.

Don’t use the root account

If anyone asks you to enable the root account, or log in as root, be very suspicious of their intentions.

In an effort to reduce these problems many Linux distributions started to encourage the use of the su command. This is variously described as being short for ‘superuser’ or ‘switch user’, and allows you to change to another user on the machine without having to log out and in again. When used with no arguments it assumes you want to change to the root user (hence the first interpretation of the name), but you can pass a username to it in order to switch to a specific user account (the second interpretation). By encouraging use of su the aim was to persuade administrators to spend most of their time using a normal account, only switch to the superuser account when they needed to, and then use the logout command (or Ctrl-D shortcut) as soon as possible to return to their user-level account.

By minimising the amount of time spent logged in as root, the use of su reduces the window of opportunity in which to make a catastrophic mistake. Despite that, human nature being what it is, many administrators have been guilty of leaving long-running terminals open in which they’ve used su to switch to the root account. In that respect su was only a small step forward for security.

Better to disable the root account entirely and then, instead of allowing long-lived terminal sessions with dangerous powers, require the user to specifically request superuser rights on a per-command basis. The key to this approach is a command called sudo (as in “switch user and do this command”).

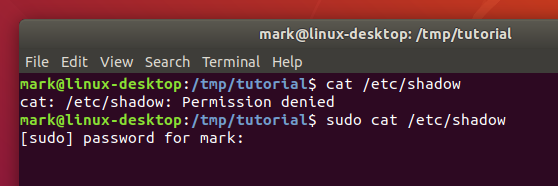

If you enter your password when prompted you should see the contents of the /etc/shadow file. Now clear the terminal by running the reset command, and run sudo cat /etc/shadow again. This time the file will be displayed without prompting you for a password, as it’s still in the cache.

Installing new software

There are lots of different ways to install software on Linux systems. Installing directly from your distro’s official software repositories is the safest option, but sometimes the application or version you want simply isn’t available that way. When installing via any other mechanism, make sure you’re getting the files from an official source for the project in question.

Increasingly, Ubuntu is making use of “snaps”, a new package format which offers some security improvements by more closely confining programs to stop them accessing parts of the system they don’t need to. But some options can reduce the security level so, if you’re asked to run snap install with any parameters other than the name of the snap, it’s worth checking exactly what the command is trying to do.

Let’s install a new command line program from the standard Ubuntu repositories to illustrate this use of sudo :

Once you’ve provided your password the apt program will print out quite a few lines of text to tell you what it’s doing. The tree program is only small, so it shouldn’t take more than a minute or two to download and install for most users. Once you are returned to the normal command line prompt, the program is installed and ready to use. Let’s run it to get a better overview of what our collection of files and folders looks like:

Going back to the command that actually installed the new program ( sudo apt install tree ) it looks slightly different to those you’ve see so far. In practice it works like this:

The sudo command, when used without any options, will assume that the first parameter is a command for it to run with superuser privileges. Any other parameters will be passed directly to the new command. sudo ‘s switches all start with one or two hyphens and must immediately follow the sudo command, so there can be no confusion about whether the second parameter on the line is a command or an option.

In this case the install command tells apt that the remainder of the command line will consist of one or more package names to install from the system’s software repositories. Usually this will add new software to the machine, but packages could be any collection of files that need to be installed to particular locations, such as fonts or desktop images.

You can put sudo in front of any command to run it as a superuser, but there’s rarely any need to. Even system configuration files can often be viewed (with cat or less ) as a normal user, and only require root privileges if you need to edit them.

8. Hidden files

Before we conclude this tutorial it’s worth mentioning hidden files (and folders). These are commonly used on Linux systems to store settings and configuration data, and are typically hidden simply so that they don’t clutter the view of your own files. There’s nothing special about a hidden file or folder, other than it’s name: simply starting a name with a dot («.») is enough to make it disappear.

You can still work with the hidden file by making sure you include the dot when you specify its file name:

Cleaning up

We’ve reached the end of this tutorial, and you should be back in your home directory now (use pwd to check, and cd to go there if you’re not). It’s only polite to leave your computer in the same state that we found it in, so as a final step, let’s remove the experimental area that we were using earlier, then double-check that it’s actually gone:

As a last step, let’s close the terminal. You can just close the window, but it’s better practice to log out of the shell. You can either use the logout command, or the Ctrl-D keyboard shortcut. If you plan to use the terminal a lot, memorising Ctrl-Alt-T to launch the terminal and Ctrl-D to close it will soon make it feel like a handy assistant that you can call on instantly, and dismiss just as easily.

9. Conclusion

This tutorial has only been a brief introduction to the Linux command line. We’ve looked at a few common commands for moving around the file system and manipulating files, but no tutorial could hope to provide a comprehensive guide to every available command. What’s more important is that you’ve learnt the key aspects of working with the shell. You’ve been introduced to some widely used terminology (and synonyms) that you might come across online, and have gained an insight into some of the key parts of a typical shell command. You’ve learnt about absolute and relative paths, arguments, options, man pages, sudo and root, hidden files and much more.

With these key concepts you should be able to make more sense of any command line instructions you come across. Even if you don’t understand every single command, you should at least have an idea of where one command stops and the next begins. You should more easily be able to tell what files they’re manipulating, or what other switches and parameters are being used. With reference to the man pages you might even be able to glean exactly what the command is doing, or at least get a general idea.

There’s little we’ve covered here that is likely to make you abandon your graphical file manager in favour of a prompt, but file manipulation wasn’t really the main goal. If, however, you’re intrigued by the ability to affect files in disparate parts of your hard drive with just a few keypresses, there’s still a lot more for you to learn.

Further reading

There are many online tutorials and commercially published books about the command line, but if you do want to go deeper into the subject a good starting point might be the following book:

The reason for recommending this book in particular is that it has been released under a Creative Commons licence, and is available to download free of charge as a PDF file, making it ideal for the beginner who isn’t sure just how much they want to commit to the command line. It’s also available as a printed volume, should you find yourself caught by the command line bug and wanting a paper reference.