How to sign language in sign language

How to sign language in sign language

Sign Language Basics for Beginners

Marley Hall is a writer and fact checker who is certified in clinical and translational research. Her work has been published in medical journals in the field of surgery, and she has received numerous awards for publication in education.

Learning sign language can be a fun experience and help you communicate with more people in the deaf and hard of hearing community. It can also lead you down many different paths.

Whether you are a beginner or an experienced signer, it’s good to understand the different aspects of the language. This includes the basic signs and techniques, where you can find resources to learn it, and the various types of sign languages used throughout the world.

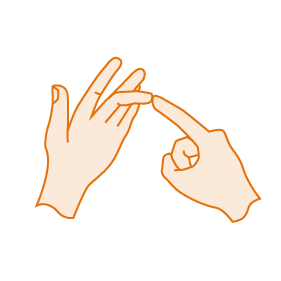

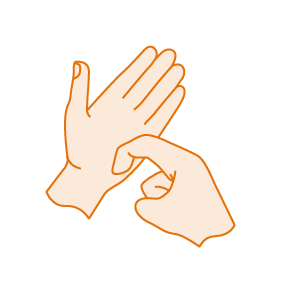

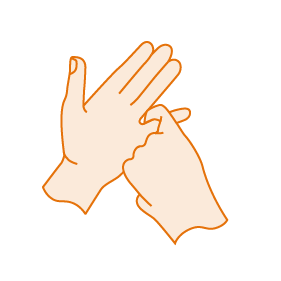

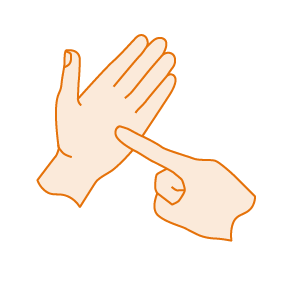

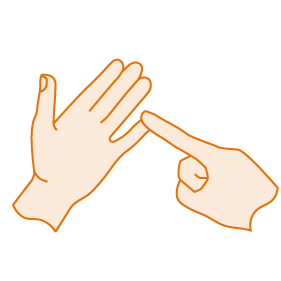

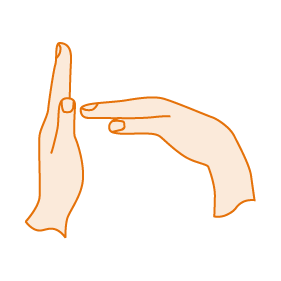

Sign Language Alphabet

Learning to sign the alphabet (known as the manual alphabet) is usually the first place to begin.

Learning Sign Language

Once you have learned to sign the alphabet, you can dive deeper into ASL. There are many ways to approach it, including online and print sign language dictionaries and classroom instruction. For many people, it’s useful to do a combination of these techniques.

As with learning any language, there is great value in attending a class. It allows you to learn from an instructor who can explain some of the finer nuances of the language that you simply won’t get from a book or website.

Fun and Expression

Sign language can also be used to have fun and there are many opportunities to be creative with the language. Examples include sign language games, creating sign language names, and «writing» ASL poetry, idioms, or ABC stories. There is even a written form of sign language that you can explore.

Practice

What good does it do to learn sign language if you don’t practice it? Like any language, if you do not use it, you lose it. The deaf or signing community offers many opportunities for practice.

You can usually learn about ways to interact with others by contacting a local resource center for deaf and hard of hearing people or a hearing and speech center. For example, signing people often enjoy going to silent or ASL dinners and coffee chats.

Different Flavors of Sign Language

It’s important to understand that sign language comes in multiple styles, much like unique dialects in a spoken language. What you sign with one person may be different than the way another person signs, and this can be confusing at times.

For instance, some people sign «true American Sign Language,» which is a language that has its own grammar and syntax. Others use signed exact English (SEE), a form that mimics the English language as closely as possible. Still others use a form of sign language that combines English with ASL, known as pidgin signed English (PSE).

Sign language is also used differently in education. Some schools may follow a philosophy known as total communication and use all means possible to communicate, not just sign language. Others believe in using sign language to teach children English, an approach known as bilingual-bicultural (bi-bi).

Prevalence

Sign language has a long history behind it and ASL actually started in Europe in the 18th century. At one time, sign language was dealt a severe blow by a historic event known as the Milan Conference of 1880. This resulted in a ban on sign language in the deaf schools of many countries.

However, a number of individuals and organizations kept the language alive. Additionally, no matter what new hearing or assistive technology comes along, sign language will survive.

There will always be a need for sign language, and its popularity has held and even grown. For example, a number of schools offer sign language as a foreign language and many offer sign language clubs as well.

Hearing Sign Language Users

While many deaf people need sign language, so do others who are not deaf. In fact, there has been a discussion in the deaf and hard of hearing community about substituting the term «signing community» for the term «deaf community» for this very reason.

Non-deaf users of sign language include hearing babies, nonverbal people who can hear but cannot talk, and even gorillas or chimpanzees. Each of these instances points to the importance of continuing the language so that communication is more inclusive.

International Sign Language

Sign language in America is not the same sign language used around the world. Most countries have their own form of sign language, such as Australia (Auslan) or China’s Chinese sign language (CSL). Often, the signs are based on the country’s spoken language and incorporate words and phrases unique to that culture.

A Word From Verywell

A desire to learn sign language can prove to be a worthy endeavor and a rewarding experience. As you begin your journey, do some research and check with local organizations that can offer you guidance in finding classes near you. This will give you a great foundation that can be fueled by practice signing with others.

How Sign Language Works

By: Jonathan Strickland | Updated: Apr 15, 2021

For centuries, people who were hard of hearing or deaf have relied on communicating with others through visual cues. As deaf communities grew, people began to standardize signs, building a rich vocabulary and grammar that exists independently of any other language. A casual observer of a conversation conducted in sign language might describe it as graceful, dramatic, frantic, comic or angry without knowing what a single sign meant.

It may seem strange to those who don’t speak sign language, but countries that share a common spoken language do not necessarily share a common sign language. American Sign Language (ASL or Ameslan) and British Sign Language (BSL) evolved independently of one another, so it would be very difficult, or even impossible, for an American deaf person to communicate with an English deaf person. However, many of the signs in ASL were adapted from French Sign Language (LSF). So a speaker of ASL in France could potentially communicate clearly with deaf people there, even though the spoken languages are completely different.

Most speakers of sign language find it difficult to learn it from books and static pictures. The way a speaker signs a concept can say more about his meaning than the sign itself. Pictures don’t capture the nuances that are intrinsic for clear communication with sign language, and sometimes it is difficult to communicate the motions some signs require without video, animation or an in-person demonstration.

In this article, we’ll focus mainly on American Sign Language, the dominant sign language in the United States. We’ll also look at Signed Exact English (SEE) and Pidgin Signed English (PSE), two alternatives to ASL that are used primarily between deaf people and hearing people. SEE and PSE rely on the English language to varying degrees. This means that unlike ASL, they are constructed, or artificial, sign languages. We’ll talk about the attempt to establish a universal sign language and look at other applications of sign language.

In the next section, we’ll explore the history of American Sign Language.

History of Sign Language

As mentioned in the previous section, French Sign Language is the origin for many of the signs used in ASL. In the early 1800s, a minister to the deaf named Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet traveled from America to Europe to learn teaching techniques. In England, he met Roch-Ambroise Cucurron, Abbé Sicard, the director of a school for the deaf in Paris. Gallaudet learned teaching methods and several signs to use in communication with the deaf and hard of hearing from Abbé Sicard. Gallaudet convinced Laurent Clerc, one of Sicard’s students, to help establish a school for the deaf in America.

Gallaudet and Clerc established the American School for the Deaf (ASD) in 1817 in Hartford, Connecticut. The school combined signs from LSF with those that had been in use by the Deaf community in America to create a standardized language. In time, this language evolved into ASL, now considered one of the most comprehensive sign languages in the world. Today, the ASD campus includes elementary, junior high and high schools.

Thomas Gallaudet’s son, Edward, founded Gallaudet University in Washington, D.C. Gallaudet was the first college for deaf and hard of hearing students. The university offers degree programs in dozens of majors for more than 1,500 students. While most students are deaf or hard of hearing, up to 5 percent of an enrolling class may consist of hearing students. ASL is the official language on campus, though there is controversy among the Deaf community concerning the ASL skill level of the staff and faculty at the university, as well as the institution’s perspective on the importance of ASL in general.

Students of ASL do not need to learn speechreading or listening skills to become proficient. ASL has its own grammar, phonology (in spoken languages, phonology is the study of sounds; in sign language, it’s the study of the basic hand signals and motions that provide the foundation of all signing), syntax and morphology (in spoken and written languages, morphology studies how words are formed from basic sounds and words; in sign language, it’s the way basic hand signals and motions. represent concepts). ASL can be interpreted into any other language. It is not normally written, though there is a system called SignWriting designed to allow speakers of ASL to communicate signs and facial expressions in a written format without translating their thoughts into another language. Learning to read English can be difficult for some deaf people, because ASL and English are not structured the same way. English uses complex rules that aren’t applicable to ASL. Not being able to hear the language can also be a major challenge in learning to read.

While it is true that you don’t have to vocalize when using sign language with someone else, most people still call the process of communicating through sign language «speaking.» In this article, we’ll use the terms speaking and signing interchangeably.

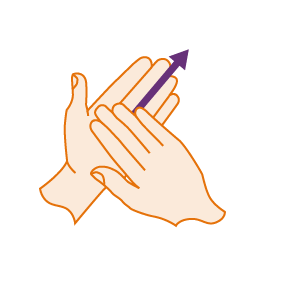

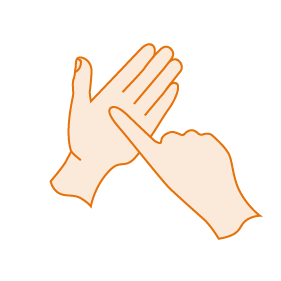

If you are the listener in a sign language conversation, you receive signs. The person signing is the speaker, and the person watching is the receiver. When receiving, you should focus on the speaker’s face and eyes, using your peripheral vision to watch hand signs. Much of the meaning in sign language comes across in facial expressions, and by focusing solely on the speaker’s hands you’ll likely misinterpret what the speaker is trying to communicate.

The Sign Language Alphabet

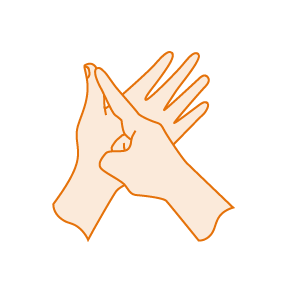

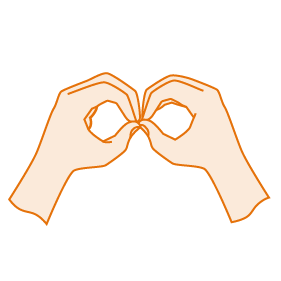

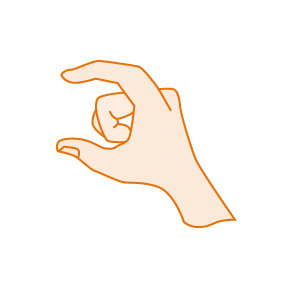

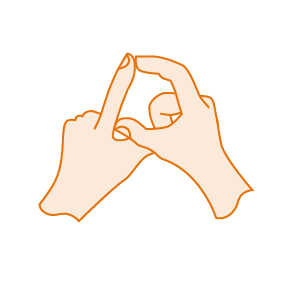

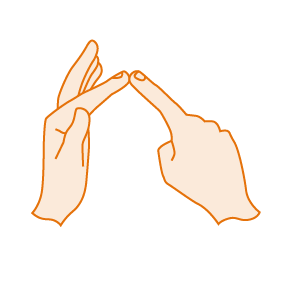

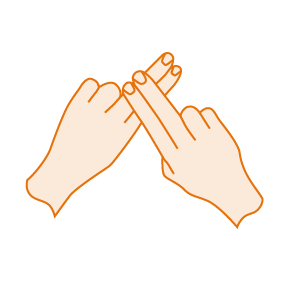

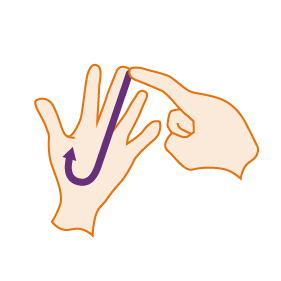

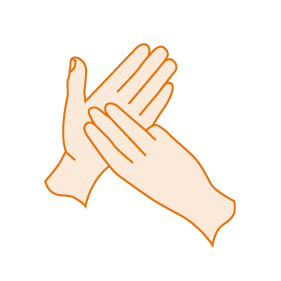

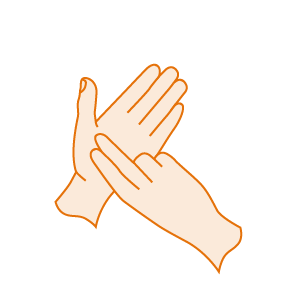

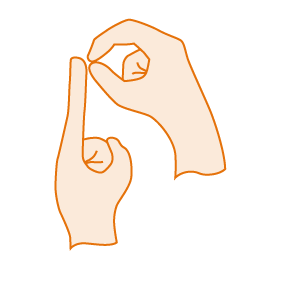

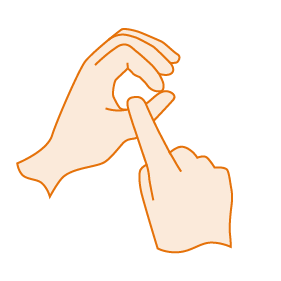

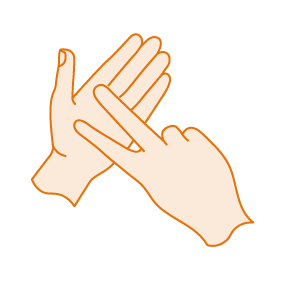

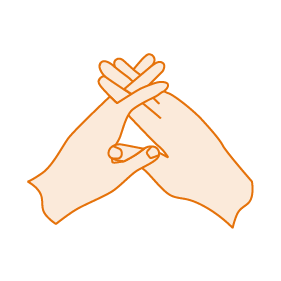

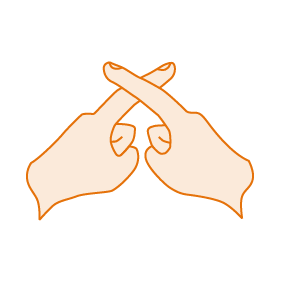

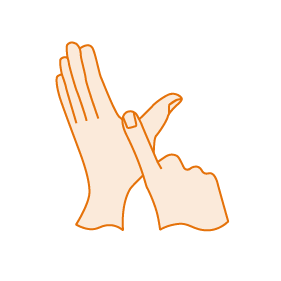

The alphabet is an important series of signs. Some hand signs for letters resemble the written form of the respective letter. When you use the hand signs for letters to spell out a word, you are finger spelling. Finger spelling is useful to convey names or to ask someone the sign for a particular concept. ASL uses one-handed signals for each letter of the alphabet (some other sign languages use both hands for some letters). Many people find finger spelling the most challenging hurdle when learning to sign, as accomplished speakers are very fast finger spellers.

To express an ongoing action, such as «thinking,» you would make the sign for «think» twice in a row. Some signs in ASL can serve as either a noun or a verb, depending on how you sign them. In general, you’d sign a verb using larger hand gestures and a noun by using smaller gestures that are doubled. At times, this can cause confusion. The sign for «food» is the same as doubling the sign for «eat,» yet the sign for «eating» is also a repeated «eat» sign. In these cases, the receiver usually knows what you mean by the context of your sentences or the size of your gestures.

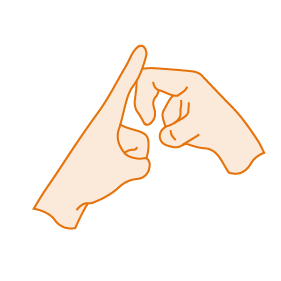

Inflections

Almost any sign can be modified. Furrowing your eyebrows, tilting your head, puffing your cheeks or shifting your body are just a few ways that you can use to change the meaning of what you are saying. Any inflection that doesn’t require your hands is called a nonmanual marker. An accomplished ASL speaker can convey a lot of information with only a few gestures coupled with nonmanual markers.

Another way to modify signs, particularly action signs, is to alter the speed with which you make the sign or by directionalizing the sign. If you make the sign for «eat» very slowly, for example, you can communicate that you took your time while eating. To directionalize concepts, you orient signs in a particular direction to communicate a specific meaning. If you wanted to communicate the English phrase «I gave you a gift» to your receiver, you would make the sign «give» towards your receiver, followed by the sign for «gift.» There is no need to make the signs for «I» or «you,» because they were understood when you directionalized the sign.

We’ll look at the grammar of ASL next.

Sign Language Words and Grammar

ASL sentences use a topic comment structure. The topic of an ASL sentence is like the subject of a sentence in English. Using the object of your sentence as the topic is called topicalization. Often the topic of an ASL sentence is a pronoun, such as I, you, he or she. An ASL speaker may sign a subject pronoun at the beginning of a sentence, the end of a sentence or both. For instance, if you were to say «I am an employee» in ASL, you could sign «I employee,» «employee I,» or «I employee I.» All three are grammatically correct in ASL.

You only need to establish the tense at the beginning of a conversation. If you wanted to tell a long story about what you did yesterday, you would sign «yesterday» at the beginning of your first sentence and go from there. Once you have designated the tense, your receivers will know that everything you sign belongs in that time until you indicate a new tense.

Tenses can vary depending on when a conversation takes place. In English you might say «I’m going to eat lunch at a restaurant this afternoon» or «Today I ate lunch at a restaurant.» In ASL, you would sign «now afternoon I eat lunch» and your audience would understand the tense depending on the current time. If you were speaking with them in the morning, they would know you were talking about future plans. On the other hand, if you were talking at night, they would know you were speaking about what you did earlier that day.

To talk about a series of events, ASL speakers can use the space in front of and behind them to indicate a timeline. Signs close to the body indicate events that happened recently or will happen soon, while signs further out indicate events that either happened long ago in the past or will happen further in the future.

If you are speaking ASL and wish to indicate a particular person as the subject of your sentence, you can use indexing. To index, you point your index finger at a person who is present (the present referent) or you can indicate someone who is not there (an absent referent). To talk about someone not in the room, you would first sign that person’s name, and then indicate a space in the area you are in to represent that person. From that moment on, when you point to that space, the person you are speaking to knows that you are talking about the person whose identity you’ve established earlier.

You punctuate sentences in ASL through pauses and facial expressions. You can punctuate questions by signing a question mark, though most speakers rely on facial expressions to indicate they’ve asked a question. For example, to ask a receiver «do you like movies,» a speaker would sign «you like movies» and raise his eyebrows.

In the next section, we’ll talk about some basic rules of etiquette when conversing in ASL.

How to learn sign language

In the hearing loss community, sign language is one of the major forms of communication used.

It consists of hand movements, hand shapes as well as facial expressions and lip patterns in order to demonstrate what people want to say.

Sign language is often used instead of spoken language in Deaf communities, as some people with hearing loss have been brought up solely using sign language to communicate with family or friends. Of course, even those with normal or limited hearing can also learn this wonderful, expressive language!

Here are my tips to learn sign language:

Types of sign language

The first thing to understand is what type of sign language you want to learn. This will most likely be based on where you live, and what verbal language is spoken in your community. Hand signs can vary based on the type of sign language being used. For example, there is American Sign Language (ASL), British Sign Language (BSL) and various others, based on different languages.

In general, sign language is grouped into three sections :

How to learn sign language

Take a sign language class

If you’re ever considering learning sign language, this is one of the best ways to do it! Often community centers, community colleges or other educational centers offer day or evening classes. Qualified sign language tutors can help you work toward sign language qualifications. Classes are also a great way to meet new people and see the signs face-to-face.

There are also online classes. Some of my HearingLikeMe writers have taken classes with ASL For You and have learned a lot through weekly Zoom classes.

Being in a class gives the opportunity to practice signing with different people. It is considered a good investment if the qualification leads to a job!

If you’re interested, research for classes in your local area or contact your local education authority.

Learn online by watching videos

Like many things these days, you can learn easily online! There are plenty of resources, like YouTube or BSL Zone where you can watch videos with sign language. Any form of video is a great way to watch and you can replay it as many times as you like, in the comfort of your own home.

Join a sign language group, deaf club or visit a deaf café

Many cities have deaf clubs or groups of deaf people who meet regularly and quite often use sign language as their form of communication. It’s a fantastic place to meet new people, who share hearing loss in common as well as the chance to polish your sign language skills. You can contact a Deaf charity or organization nearby, or search for a group using websites such as Meetup.com to find a group for you.

Take an online course

Online courses can be an alternative to day or evening classes that you take in-person. Some Deaf organizations and universities provide these, so do some research to find the best course for you. For example, Gallaudet University has a free online course to learn ASL.

Online courses are more flexible because they can be done in your own time, or in the comfort of your own home. You can practice as much as you need, and there is often no pressure to complete it.

Hire a private, qualified sign language tutor

If you want to learn sign language quickly, a private tutor could be the best way. Research local, qualified sign language tutors in your area who are willing to offer private tuition. Courses could be done in one-to-one sessions, or in small groups of your choice. You may find a private tutor more of a benefit if you find a large class environment is too difficult to learn in.

Watch and mimic interpreters

You can easily pick up signs by watching others, particularly sign language interpreters. You can often find them at deaf events or on TV during special, live events. Some TV shows also utilize sign language, such as “Switched at Birth.”

Ask your Deaf friends and family teach you

Asking a Deaf friend to teach you some sign language is a great way of making new Deaf friends! If you know friends or family use sign language already, asking them to teach you some signs will also remove some stresses from the struggle of oral/spoken conversation with them – making the exchange beneficial for both of you.

Just make sure your friend or family member uses sign language before asking them, as not all people who have hearing loss know sign language.

Use an App

There are also a few apps available to learn sign language on!

My favorite is the ‘Sign BSL’ app, which is a British Sign Language Dictionary app. If you don’t know how to sign a word, you can search for it on the app so it’s a great resource.

There are also great apps for ASL learners. The language learning platform, Drops, released ASL on their Scripts app in conjunction with the United Nations’ International Day of Sign Languages The app teaches learners how to read and write alphabets and character-based language systems.

Drops’ ASL offering on Scripts is free for 5 minutes a day, allowing anyone with the Scripts app the ability to quickly learn the ASL alphabet. By associating illustrations of the signs to their meanings and testing users through fun, 5-minute games, Drops is bringing their acclaimed learning approach to an even broader audience and leveraging its global, multi-million user base to bring global awareness and access to ASL.

Read a Book

If you’re not a fan of online learning, there are plenty of books available at bookshops and libraries. There are varieties from Sign Language dictionaries, books for children, step by step learning and so much more!

These, however, may be more difficult to learn from, as the movements for the signs are not as obvious to see, in contrast to watching a video.

Watch a video/DVD

Yet another suggestion is watching a video or DVD or pre-recorded sign language learning video. Some organizations have created videos or DVDs especially to help you learn the language properly. If you’re not sure which one to get, why not contact a Deaf organization or visit your local library.

A few more tips to learn sign language

Once you’ve found your preferred language learning method, you need to be aware of a few things to successfully use sign language.

Now that you’ve got a basis on how to learn sign language, I hope you can find local or online resources to do so! Remember to have fun while learning, and communicate with other sign language users. You will be well on your way to make new friends, communicate with others and grow your own language comprehension!

Sign language

This page explains the basics of sign language, including how it works, who uses it and how to learn it.

What is sign language?

Sign language is a way of communicating using hand gestures and movements, body language and facial expressions, instead of spoken words.

Like any spoken language, such as Italian or Spanish, there are lots of different sign languages across the world.

Try using sign language!

Who uses sign language?

Sign language is used mainly by people who are Deaf or have hearing impairments.

British Sign Language

In the UK, “sign language” usually refers to British Sign Language (BSL), the most common sign language, used by around 125,000 people.

For over 87,000 Deaf people, BSL is their first language and English is their second or maybe even third language.

In Northern Ireland, Irish Sign Language (ISL) is used as well as BSL. Find out more about ISL on the Irish Deaf Society website.

BSL, like all sign language, is more than hand shapes and movements. Lip patterns, facial expressions and shoulder movements are important too.

Since 2003, BSL has been recognised as a language in its own right. It is a complete language, with its own vocabulary, grammar and word order, as well as its own social beliefs, behaviours, art, history and values.

If you were born deaf, you probably learned BSL as your first language.

BSL is the language of the Deaf community, who use a capital D to express pride in their identity.

In BSL, you start with the main subject or topic. Then, you say something about it.

So, for example, in English, you say:

Q: “What is your name?”

A: “My name is George.”

But in BSL, you say:

Q: “Name – what?”

A: “Name me George.”

Before you read on…

Fingerspelling

Fingerspelling is the BSL alphabet. Every letter of the alphabet has a sign.

You can use these letter signs to spell out words – often names and places – and sentences on your hand.

Fingerspelling is an easy way to communicate if you don’t know or can’t remember some BSL signs.

“It was such a rewarding moment when Sam signed ‘more’ to get extra time on the swing.

“We’d been immersing Sam in sign language for months and months, not by giving him lists of words to learn, but by talking and signing our conversations so he got used to language and how to ask for what he wanted.

“He really appreciated someone making the effort to try and communicate with him. Finally, he started using it himself!”

Sarah Turpin, senior MSI practitioner, Sense

Say hello to George

Watch George using BSL and fingerspelling.

Hands-on BSL

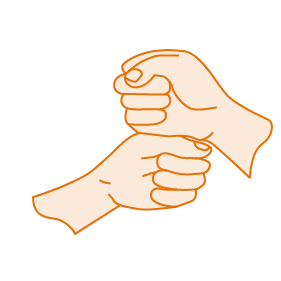

If you are blind or have limited vision and you can’t see signing at a distance, you can use hands-on BSL.

With hands-on BSL, you and the person you’re communicating with use the BSL signs on each other’s hands, not on your own.

Say hello to Helene

Watch Helene using hands-on signing as one of the ways she communicates. She also explains how you can say hello to her using block, another fingerspelling alphabet

Sign Supported English (SSE)

Sign Supported English (SSE) borrows BSL signs but uses them in the order they are used in spoken English.

Sense Sign School is now in session!

Get fun monthly lessons in British Sign Language delivered to your door and online.

How can I learn British Sign Language?

The best way to learn BSL is on a course taught by a qualified BSL tutor fluent in the language. Most BSL tutors are deaf and hold a relevant teaching qualification.

Courses are held in colleges, universities, schools, Deaf clubs and community centres. Some are basic introductions to BSL, but most offer qualifications.

Sense Sign School is a fun way to learn BSL at home, with lessons and activities delivered to your door.

Courses offering qualifications are usually part-time or evening classes, running from September to June.

Intensive courses, with daytime or weekend classes, are also available.

Where can I find out about courses?

You can find out more about BSL courses in your area from Signature.

Sign up to our newsletter

Find out more about communication methods and read inspiring stories about the people that use them.

Signature

Signature is a national charity and the leading awarding body for deaf communication qualifications in the UK.

All Signature qualifications are nationally recognised and accredited by Ofqual.

With almost 40 years’ experience, Signature has supported more than 450,000 people to learn BSL.

BSL interpreters

BSL interpreters enable communication between Deaf sign language users and hearing people.

If you need to book an interpreter, check they are registered with either:

Top tips for British Sign Language

Using British Sign Language

Other ways of communicating

Using speech

Using touch

Using signs

Also

More information

This content was last reviewed in April 2022. We’ll review it again next year.

Sense is here for everyone living with complex disabilities. For everyone who is deafblind.

Everything we do supports individuals to express themselves, to develop their skills and confidence, to make choices and to live a full life.

Stay informed

We’d love to stay in touch with stories, news from our campaigns, ways to get involved and more sent to your inbox.

Contact us

Sense

101 Pentonville Road

London N1 9LG

750 Bristol Road

Birmingham B29 6NA

Sense is a registered charity number 289868. Registered as a company limited by guarantee in England and Wales number 01825301.

Registered office at 101 Pentonville Road, London N1 9LG. Copyright © 2022 Sense

Sign language

This page either needs to be altered to become the main page of a book, or altered to fit the «local manual of style» of the book it is to be included in.

Please remove <

A sign language (also signed language) is a language which, instead of acoustically conveyed sound patterns, uses visually transmitted sign patterns (manual communication, body language and lip patterns) to convey meaning—simultaneously combining hand shapes, orientation and movement of the hands, arms or body, and facial expressions to fluidly express a speaker’s thoughts. Sign languages commonly develop in deaf communities, which can include interpreters and friends and families of deaf people as well as people who are deaf or hard of hearing themselves.

Wherever communities of deaf people exist, sign languages develop. In fact, their complex spatial grammars are markedly different from the grammars of spoken languages. Hundreds of sign languages are in use around the world and are at the cores of local Deaf cultures. Some sign languages have obtained some form of legal recognition, while others have no status at all.

In addition to sign languages, various signed codes of spoken languages have been developed, such as Signed English and Warlpiri Sign Language. [1] These are not to be confused with languages, oral or signed; a signed code of an oral language is simply a signed mode of the language it carries, just as a writing system is a written mode. Signed codes of oral languages can be useful for learning oral languages or for expressing and discussing literal quotations from those languages, but they are generally too awkward and unwieldy for normal discourse. For example, a teacher and deaf student of English in the United States might use Signed English to cite examples of English usage, but the discussion of those examples would be in American Sign Language.

Several culturally well developed sign languages are a medium for stage performances such as sign-language poetry. Many of the poetic mechanisms available to signing poets are not available to a speaking poet.

Contents

History of sign language [ edit | edit source ]

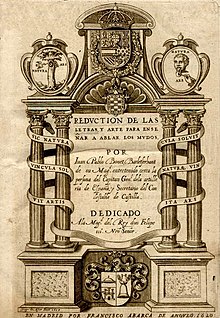

The written history of sign language began in the 17th century in Spain. In 1620, Juan Pablo Bonet published Reducción de las letras y arte para enseñar a hablar a los mudos (‘Reduction of letters and art for teaching mute people to speak’) in Madrid. It is considered the first modern treatise of Phonetics and Logopedia, setting out a method of oral education for the deaf people by means of the use of manual signs, in form of a manual alphabet to improve the communication of the mute or deaf people.

From the language of signs of Bonet, Charles-Michel de l’Épée published his alphabet in the 18th century, which has survived basically unchanged until the present time.

In 1755, Abbé de l’Épée founded the first private school for deaf children in Paris; Laurent Clerc was arguably its most famous graduate. He went to the United States with Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet to found the American School for the Deaf in Hartford, Connecticut. [2] Gallaudet’s son, Edward Miner Gallaudet founded a school for the deaf in 1857, which in 1864 became Gallaudet University in Washington, DC, the only liberal arts university for and of the deaf in the world.

Generally, each spoken language has a sign language counterpart in as much as each linguistic population will contain Deaf members who will generate a sign language. In much the same way that geographical or cultural forces will isolate populations and lead to the generation of different and distinct spoken languages, the same forces operate on signed languages and so they tend to maintain their identities through time in roughly the same areas of influence as the local spoken languages. This occurs even though sign languages have no relation to the spoken languages of the lands in which they arise. There are notable exceptions to this pattern, however, as some geographic regions sharing a spoken language have multiple, unrelated signed languages. Variations within a ‘national’ sign language can usually be correlated to the geographic location of residential schools for the deaf.

International Sign, formerly known as Gestuno, is used mainly at international Deaf events such as the Deaflympics and meetings of the World Federation of the Deaf. Recent studies claim that while International Sign is a kind of a pidgin, they conclude that it is more complex than a typical pidgin and indeed is more like a full signed language. [3]

Linguistics of sign [ edit | edit source ]

In linguistic terms, sign languages are as rich and complex as any oral language, despite the common misconception that they are not «real languages». Professional linguists have studied many sign languages and found them to have every linguistic component required to be classed as true languages. [4]

Sign languages, like oral languages, organize elementary, meaningless units (phonemes; once called cheremes in the case of sign languages) into meaningful semantic units. The elements of a sign are Handshape (or Handform), Orientation (or Palm Orientation), Location (or Place of Articulation), Movement, and Non-manual markers (or Facial Expression), summarised in the acronym HOLME.

Common linguistic features of deaf sign languages are extensive use of classifiers, a high degree of inflection, and a topic-comment syntax. Many unique linguistic features emerge from sign languages’ ability to produce meaning in different parts of the visual field simultaneously. For example, the recipient of a signed message can read meanings carried by the hands, the facial expression and the body posture in the same moment. This is in contrast to oral languages, where the sounds that comprise words are mostly sequential (tone being an exception).

Sign languages’ relationships with oral languages [ edit | edit source ]

A common misconception is that sign languages are somehow dependent on oral languages, that is, that they are oral language spelled out in gesture, or that they were invented by hearing people. Hearing teachers in deaf schools, such as Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet, are often incorrectly referred to as “inventors” of sign language.

Manual alphabets (fingerspelling) are used in sign languages, mostly for proper names and technical or specialised vocabulary borrowed from spoken languages. The use of fingerspelling was once taken as evidence that sign languages were simplified versions of oral languages, but in fact it is merely one tool among many. Fingerspelling can sometimes be a source of new signs, which are called lexicalized signs.

On the whole, deaf sign languages are independent of oral languages and follow their own paths of development. For example, British Sign Language and American Sign Language are quite different and mutually unintelligible, even though the hearing people of Britain and America share the same oral language.

Similarly, countries which use a single oral language throughout may have two or more sign languages; whereas an area that contains more than one oral language might use only one sign language. South Africa, which has 11 official oral languages and a similar number of other widely used oral languages is a good example of this. It has only one sign language with two variants due to its history of having two major educational institutions for the deaf which have served different geographic areas of the country.

Spatial grammar and simultaneity [ edit | edit source ]

Sign languages exploit the unique features of the visual medium (sight). Oral language is linear. Only one sound can be made or received at a time. Sign language, on the other hand, is visual; hence a whole scene can be taken in at once. Information can be loaded into several channels and expressed simultaneously. As an illustration, in English one could utter the phrase, «I drove here». To add information about the drive, one would have to make a longer phrase or even add a second, such as, «I drove here along a winding road,» or «I drove here. It was a nice drive.» However, in American Sign Language, information about the shape of the road or the pleasing nature of the drive can be conveyed simultaneously with the verb ‘drive’ by inflecting the motion of the hand, or by taking advantage of non-manual signals such as body posture and facial expression, at the same time that the verb ‘drive’ is being signed. Therefore, whereas in English the phrase «I drove here and it was very pleasant» is longer than «I drove here,» in American Sign Language the two may be the same length.

In fact, in terms of syntax, ASL shares more with spoken Japanese than it does with English. [6]

Use of signs in hearing communities [ edit | edit source ]

Gesture is a typical component of spoken languages. More elaborate systems of manual communication have developed in places or situations where speech is not practical or permitted, such as cloistered religious communities, scuba diving, television recording studios, loud workplaces, stock exchanges, baseball, hunting (by groups such as the Kalahari bushmen), or in the game Charades. In Rugby Union the Referee uses a limited but defined set of signs to communicate his/her decisions to the spectators. Recently, there has been a movement to teach and encourage the use of sign language with toddlers before they learn to talk, because such young children can communicate effectively with signed languages well before they are physically capable of speech. This is typically referred to as Baby Sign. There is also movement to use signed languages more with non-deaf and non-hard-of-hearing children with other causes of speech impairment or delay, for the obvious benefit of effective communication without dependence on speech.

On occasion, where the prevalence of deaf people is high enough, a deaf sign language has been taken up by an entire local community. Famous examples of this include Martha’s Vineyard Sign Language in the USA, Kata Kolok in a village in Bali, Adamorobe Sign Language in Ghana and Yucatec Maya sign language in Mexico. In such communities deaf people are not socially disadvantaged.

Many Australian Aboriginal sign languages arose in a context of extensive speech taboos, such as during mourning and initiation rites. They are or were especially highly developed among the Warlpiri, Warumungu, Dieri, Kaytetye, Arrernte, and Warlmanpa, and are based on their respective spoken languages.

A pidgin sign language arose among tribes of American Indians in the Great Plains region of North America (see Plains Indian Sign Language). It was used to communicate among tribes with different spoken languages. There are especially users today among the Crow, Cheyenne, and Arapaho. Unlike other sign languages developed by hearing people, it shares the spatial grammar of deaf sign languages.

Telecommunications facilitated signing [ edit | edit source ]

One of the first demonstrations of the ability for telecommunications to help sign language users communicate with each other occurred when AT&T’s videophone (trademarked as the ‘Picturephone’) was introduced to the public at the 1964 New York World’s Fair –two deaf users were able to freely communicate with each other between the fair and another city. [7] Various organizations have also conducted research on signing via videotelephony.

Sign language interpretation services via Video Remote Interpreting (VRI) or a Video Relay Service (VRS) are useful in the present-day where one of the parties is deaf, hard-of-hearing or speech-impaired (mute). In such cases the interpretation flow is normally within the same principal language, such as French Sign Language (FSL) to spoken French, Spanish Sign Language (SSL) to spoken Spanish, British Sign Language (BSL) to spoken English, and American Sign Language (ASL) also to spoken English (since BSL and ASL are completely distinct), etc. Multilingual sign language interpreters, who can also translate as well across principal languages (such as to and from SSL, to and from spoken English), are also available, albeit less frequently. Such activities involve considerable effort on the part of the translator, since sign languages are distinct natural languages with their own construction and syntax, different from the aural version of the same principal language.

With video interpreting, sign language interpreters work remotely with live video and audio feeds, so that the interpreter can see the deaf or mute party, and converse with the hearing party, and vice versa. Much like telephone interpreting, video interpreting can be used for situations in which no on-site interpreters are available. However, video interpreting cannot be used for situations in which all parties are speaking via telephone alone. VRI and VRS interpretation requires all parties to have the necessary equipment. Some advanced equipment enables interpreters to remotely control the video camera, in order to zoom in and out or to point the camera toward the party that is signing.

Home sign [ edit | edit source ]

Sign systems are sometimes developed within a single family. For instance, when hearing parents with no sign language skills have a deaf child, an informal system of signs will naturally develop, unless repressed by the parents. The term for these mini-languages is home sign (sometimes homesign or kitchen sign). [8]

Home sign arises due to the absence of any other way to communicate. Within the span of a single lifetime and without the support or feedback of a community, the child naturally invents signals to facilitate the meeting of his or her communication needs. Although this kind of system is grossly inadequate for the intellectual development of a child and it comes nowhere near meeting the standards linguists use to describe a complete language, it is a common occurrence. No type of Home Sign is recognized as an official language.

Classification of sign languages [ edit | edit source ]

Although deaf sign languages have emerged naturally in deaf communities alongside or among spoken languages, they are unrelated to spoken languages and have different grammatical structures at their core. A group of sign «languages» known as manually coded languages are more properly understood as signed modes of spoken languages, and therefore belong to the language families of their respective spoken languages. There are, for example, several such signed encodings of English.

There has been very little historical linguistic research on sign languages, and few attempts to determine genetic relationships between sign languages, other than simple comparison of lexical data and some discussion about whether certain sign languages are dialects of a language or languages of a family. Languages may be spread through migration, through the establishment of deaf schools (often by foreign-trained educators), or due to political domination.

Language contact is common, making clear family classifications difficult — it is often unclear whether lexical similarity is due to borrowing or a common parent language. Contact occurs between sign languages, between signed and spoken languages (Contact Sign), and between sign languages and gestural systems used by the broader community. One author has speculated that Adamorobe Sign Language may be related to the «gestural trade jargon used in the markets throughout West Africa», in vocabulary and areal features including prosody and phonetics. [9]

The only comprehensive classification along these lines going beyond a simple listing of languages dates back to 1991. [11] The classification is based on the 69 sign languages from the 1988 edition of Ethnologue that were known at the time of the 1989 conference on sign languages in Montreal and 11 more languages the author added after the conference. [12]

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/image01-89a8b858fa164fbe8202b016aeb22f47.jpeg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/sign-language-instructions-90286885-5772d07c5f9b585875eac85d.jpg)