How to value private company

How to value private company

How to Value Private Companies

Kirsten Rohrs Schmitt is an accomplished professional editor, writer, proofreader, and fact-checker. She has expertise in finance, investing, real estate, and world history. Throughout her career, she has written and edited content for numerous consumer magazines and websites, crafted resumes and social media content for business owners, and created collateral for academia and nonprofits. Kirsten is also the founder and director of Your Best Edit; find her on LinkedIn and Facebook.

Determining the market value of a publicly-traded company can be done by multiplying its stock price by its outstanding shares. That’s easy enough. But the process for private companies isn’t as straightforward or transparent. Private companies don’t report their financials publicly, and since there’s no stock listed on an exchange, it’s often difficult to determine the value for the company. Continue reading to find out more about private companies and some of the ways in which they’re valued.

Key Takeaways

Why Value Private Companies?

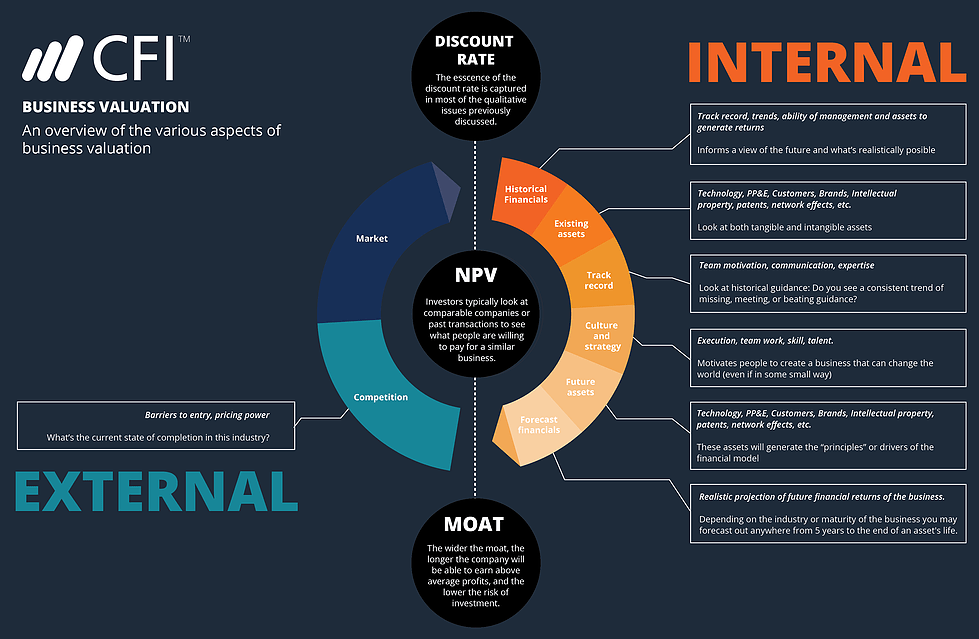

Valuations are an important part of business, for companies themselves, but also for investors. For companies, valuations can help measure their progress and success, and can help them track their performance in the market compared to others. Investors can use valuations to help determine the worth of potential investments. They can do this by using data and information made public by a company. Regardless of who the valuation is for, it essentially describes the company’s worth.

As we mentioned above, determining the value of a public company is relatively simpler compared to private companies. That’s because of the amount of data and information made available by public companies.

Private vs. Public Ownership

The most obvious difference between privately-held and publicly-traded companies is that public firms have sold at least a portion of the firm’s ownership during an initial public offering (IPO). An IPO gives outside shareholders an opportunity to purchase a stake in the company or equity in the form of stock. Once the company goes through its IPO, shares are then sold on the secondary market to the general pool of investors.

The ownership of private companies, on the other hand, remains in the hands of a select few shareholders. The list of owners typically includes the companies’ founders, family members in the case of a family business, along with initial investors such as angel investors or venture capitalists. Private companies don’t have the same requirements as public companies do for accounting standards. This makes it easier to report than if the company went public.

Valuing Private Companies

Private vs. Public Reporting

Public companies must adhere to accounting and reporting standards. These standards—stipulated by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC)—include reporting numerous filings to shareholders including annual and quarterly earnings reports and notices of insider trading activity.

Private companies are not bound by such stringent regulations. This allows them to conduct business without having to worry so much about SEC policy and public shareholder perception. The lack of strict reporting requirements is one of the major reasons why private companies remain private.

Raising Capital

Public Market

The biggest advantage of going public is the ability to tap the public financial markets for capital by issuing public shares or corporate bonds. Having access to such capital can allow public companies to raise funds to take on new projects or expand the business.

Owning Private Equity

Although private companies are not typically accessible to the average investor, there are times when private firms may need to raise capital. As a result, they may need to sell part of the ownership in the company. For example, private companies may elect to offer employees the opportunity to purchase stock in the company as compensation by making shares available for purchase.

Privately-held firms may also seek capital from private equity investments and venture capital. In such a case, those investing in a private company must be able to estimate the firm’s value before making an investment decision. In the next section, we’ll explore some of the valuation methods of private companies used by investors.

Comparable Valuation of Firms

The most common way to estimate the value of a private company is to use comparable company analysis (CCA). This approach involves searching for publicly-traded companies that most closely resemble the private or target firm.

The process includes researching companies of the same industry, ideally a direct competitor, similar size, age, and growth rate. Typically, several companies in the industry are identified that are similar to the target firm. Once an industry group is established, averages of their valuations or multiples can be calculated to provide a sense of where the private company fits within its industry.

For example, if we were trying to value an equity stake in a mid-sized apparel retailer, we would look for public companies of similar size and stature with the target firm. Once the peer group is established, we would calculate the industry averages including operating margins, free-cash-flow and sales per square foot—an important metric in retail sales.

Private Equity Valuation Metrics

Equity valuation metrics must also be collected, including price-to-earnings, price-to-sales, price-to-book, and price-to-free cash flow. The EBITDA multiple can help in finding the target firm’s enterprise value (EV)—which is why it’s also called the enterprise value multiple. This provides a much more accurate valuation because it includes debt in its value calculation.

The enterprise multiple is calculated by dividing the enterprise value by the company’s earnings before interest taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA). The company’s enterprise value is sum of its market capitalization, value of debt, (minority interest, preferred shares subtracted from its cash and cash equivalents.

If the target firm operates in an industry that has seen recent acquisitions, corporate mergers, or IPOs, we can use the financial information from those transactions to calculate a valuation. Since investment bankers and corporate finance teams have already determined the value of the target’s closest competitors, we can use their findings to analyze companies with comparable market share to come up with an estimate of the target’s firm’s valuation.

While no two firms are the same, by consolidating and averaging the data from the comparable company analysis, we can determine how the target firm compares to the publicly-traded peer group. From there, we’re in a better position to estimate the target firm’s value.

Estimating Discounted Cash Flow

The discounted cash flow method of valuing a private company, the discounted cash flow of similar companies in the peer group is calculated and applied to the target firm. The first step involves estimating the revenue growth of the target firm by averaging the revenue growth rates of the companies in the peer group.

This can often be a challenge for private companies due to the company’s stage in its lifecycle and management’s accounting methods. Since private companies are not held to the same stringent accounting standards as public firms, private firms’ accounting statements often differ significantly and may include some personal expenses along with business expenses—not uncommon in smaller family-owned businesses—along with owner salaries, which will also include the payment of dividends to ownership.

Once revenue has been estimated, we can estimate expected changes in operating costs, taxes and working capital. Free cash flow can then be calculated. This provides the operating cash remaining after capital expenditures have been deducted. Free cash flow is typically used by investors to determine how much money is available to give back to shareholders in, for example, the form of dividends.

Calculating Beta for Private Firms

The next step would be to calculate the peer group’s average beta, tax rates, and debt-to-equity (D/E) ratios. Ultimately, the weighted average cost of capital (WACC) needs to be calculated. The WACC calculates the average cost of capital whether it’s financed through debt and equity.

The cost of equity can be estimated using the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM). The cost of debt will often be determined by examining the target’s credit history to determine the interest rates being charged to the firm. The capital structure details including the debt and equity weightings, as well as the cost of capital from the peer group also need to be factored into the WACC calculations.

Determining Capital Structure

Although determining the target’s capital structure can be difficult, industry averages can help in the calculations. However, it’s likely that the costs of equity and debt for the private firm will be higher than its publicly-traded counterparts, so slight adjustments may be required to the average corporate structure to account for these inflated costs. Often, a premium is added to the cost of equity for a private firm to compensate for the lack of liquidity in holding an equity position in the firm.

Once the appropriate capital structure has been estimated, the WACC can be calculated. The WACC provides the discount rate for the target firm so that by discounting the target’s estimated cash flows, we can establish a fair value of the private firm. The illiquidity premium, as previously mentioned, can also be added to the discount rate to compensate potential investors for the private investment.

Private company valuations may not be accurate because they rely on assumptions and estimations.

Problems With Private Company Valuations

While there may be some valid ways we can value private companies, it isn’t an exact science. That’s because these calculations are merely based on a series of assumptions and estimates. Moreover, there may be certain one-time events that may affect a comparable firm, which can sway a private company’s valuation. These kind of circumstances are often hard to factor in, and generally require more reliability. Public company valuations, on the other hand, tend to be much more concrete because their values are based on actual data.

The Bottom Line

As you can see, the valuation of a private firm is full of assumptions, best guess estimates, and industry averages. With the lack of transparency involved in privately-held companies, it’s a difficult task to place a reliable value on such businesses. Several other methods exist that are used in the private equity industry and by corporate finance advisory teams to determine the valuations of private companies.

Private Company Valuation

Three methods for valuating private companies

What is Private Company Valuation?

Private company valuation is the set of procedures used to appraise a company’s current net worth. For public companies, this is relatively straightforward: we can simply retrieve the company’s stock price and the number of shares outstanding from databases such as Google Finance. The value of the public company, also called market capitalization, is the product of the said two values.

Such an approach, however, will not work with private companies, since information regarding their stock value is not publicly listed. Moreover, as privately held firms often are not required to operate by the stringent accounting and reporting standards that govern public firms, their financial statements may be inconsistent and unstandardized, and as such, are more difficult to interpret.

Here, we will introduce three common methods for valuing private companies, using data available to the public.

Common Methods for Valuing Private Companies

#1 Comparable Company Analysis (CCA)

The Comparable Company Analysis (CCA) method operates under the assumption that similar firms in the same industry have similar multiples. When the financial information of the private company is not publicly available, we search for companies that are similar to our target valuation and determine the value of the target firm using the comparable firms’ multiples. This is the most common private company valuation method.

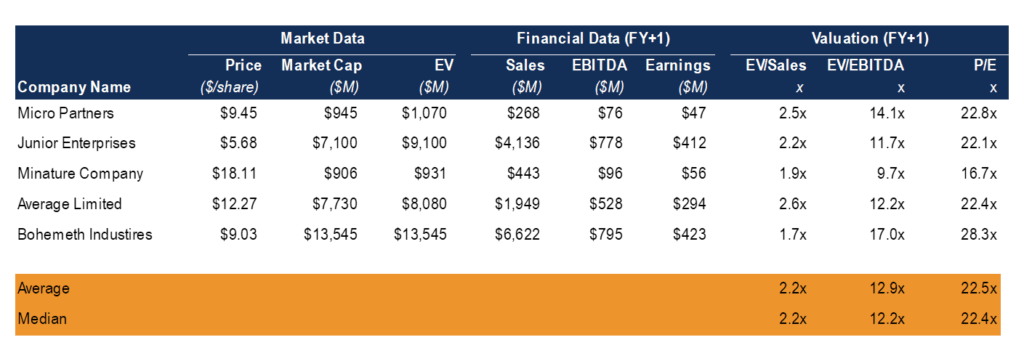

To apply this method, we first identify the target firm’s characteristics in size, industry, operation, etc., and establish a “peer group” of companies that share similar characteristics. We then collect the multiples of these companies and calculate the industry average. While the choices of multiples can depend on the industry and growth stage of firms, we hereby provide an example of valuation using the EBITDA multiple, as it is one of the most commonly used multiples.

The EBITDA is a firm’s net income adjusted for interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization, and can be used as an approximate representation of said firm’s free cash flow. The firm’s valuation formula is expressed as follows:

Value of target firm = Multiple (M) x EBITDA of the target firm

Where, the Multiple (M) is the average of Enterprise Value/EBITDA of comparable firms, and the EBITDA of the target firm is typically projected for the next twelve months.

The image shown above is a Comps Table from CFI’s Business Valuation Course.

#2 Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) method

The Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) method takes the CCA method one-step further. As with the CCA method, we estimate the target’s discounted cash flow estimations, based on acquired financial information from its publicly-traded peers.

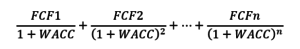

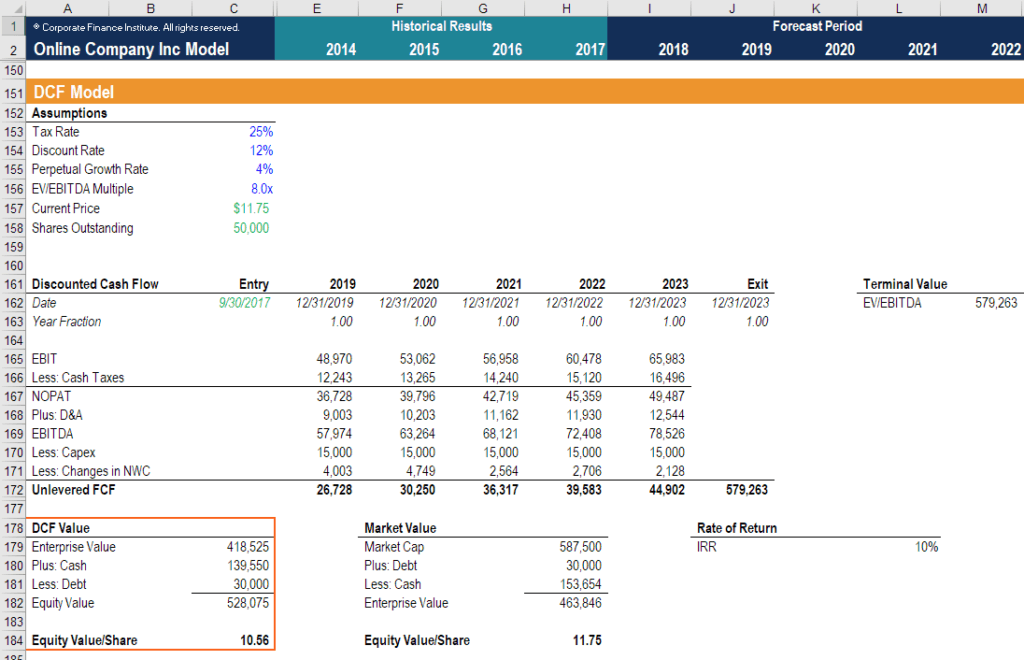

Under the DCF method, we start by determining the applicable revenue growth rate for the target firm. This is achieved by calculating the average growth rates of the comparable firms. We then make projections of the firm’s revenue, operating expenses, taxes, etc., and generate free cash flows (FCF) of the target firm, typically for 5 years. The formula of free cash flow is given as:

Free cash flow = EBIT (1-tax rate) + (depreciation) + (amortization) – (change in net working capital) – (capital expenditure)

We usually use the firm’s weighted average cost of capital (WACC) as the appropriate discount rate. To derive a firm’s WACC, we need to know its cost of equity, cost of debt, tax rate, and capital structure. Cost of equity is calculated using the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM). We estimate the firm’s beta by taking the industry average beta. Cost of debt is dependent on the target’s credit profile, which affects the interest rate at which it incurs debt.

We also refer to the target’s public peers to find the industry norm of tax rate and capital structure. Once we have the weights of debt and equity, cost of debt, and cost of equity, we can derive the WACC.

With all the above steps completed, the valuation of the target firm can be calculated as:

It should be noted that performing a DCF analysis requires significant financial modeling experience. The best way to learn financial modeling is through practice and direct instruction from a professional. CFI’s financial modeling course is one of the easiest ways to learn this skill.

#3 First Chicago Method

The First Chicago Method is a combination of the multiple-based valuation method and the discounted cash flow method. The distinct feature of this method lies in its consideration of various scenarios of the target firm’s payoffs. Usually, this method involves the construction of three scenarios: a best-case (as stated in the firm’s business plan), a base-case (the most likely scenario), and a worst-case scenario. A probability is assigned to each case.

We apply the same approach in the first two methods to project case-specific cash flows and growth rates for several years (typically a five-year forecast period). We also project the terminal value of the firm using the Gordon Growth Model. Subsequently, the valuation of each case is derived using the DCF method. Finally, we arrive at the valuation of the target firm by taking the probability-weighted average of the three scenarios.

This private company valuation method can be used by venture capitalists and private equity investors as it provides a valuation that incorporates both the firm’s upside potential and downside risk.

Limitation and Application in the Real World

As we can see, private company valuation is primarily constructed from assumptions and estimations. While taking the industry average on multiples and growth rates provides a decent guess for the true value of the target firm, it cannot account for extreme one-time events that affected the comparable public firm’s value. As such, we need to adjust for a more reliable rate, excluding the effects of such rare events.

Additionally, recent transactions in the industry such as acquisitions, mergers, or IPOs can provide us with financial information that gives a far more sophisticated estimate of the target firm’s worth.

Learn More!

We hope this has been a helpful guide to private company valuation. To keep learning more about how to value a business, we highly recommend these additional resources below:

Valuation Techniques

Learn the most important valuation techniques in CFI’s Business Valuation course!

Step by step instruction on how the professionals on Wall Street value a company.

the easy way with templates and step by step instruction!

How to Value a Private Company: The Best Guide

When it comes to Private Company Valuation, One of the questions you could meet in job interviews is “How to value a private company”?

This question relates to how much you know about mergers and acquisitions and its valuation.

Though there’s a lot of things that should be taken into account when valuing a private entity, we’re going to be presenting here the important things you should know if you want to brief yourself or improve your knowledge on valuing private companies.

After all, a career in M&A is one of the lucrative areas in finance.

You should know first that there are two types of target companies, Add-ons, and Platforms.

Add-ons vs. Platforms Companies

Platform acquisition companies are those companies that have established reputation and distribution markets. Buyer companies would buy them as a strategic way of increasing their current market scope.

Add-on acquisition companies are underperforming companies due to continuous losses, management inability, lack of infrastructure or for any other reasons.

They are being bought by buyer companies in anticipation that the buyer company could greatly increase the profitability of the add-on target company.

The acquirer usually has wide market reach, big infrastructure, and expert management.

Aside from the anticipation of the increase in market value, add-ons are also bought to provide complementing technology or services to the acquirer company.

Valuation of both types of targets doesn’t require different valuation techniques. The difference is how an analyst would estimate the future cash flow of the company being valued.

Add-ons would be having more volatility in cash flows than platform companies.

Add-ons would require a more in-depth, more accurate and more conservative approach in valuation because of the cash flow uncertainties.

Aside from that, the acquirer would outlay more cash than it would be had the target company been a platform company.

Another challenge posed in acquiring add-on companies is that most likely, distressed companies would require higher valuations because they need to pay a lot of debts.

Right negotiation comes into play into these kinds of scenarios.

But, in conclusion, there’s really no good argument as to which one is better to buy- an add-on or a platform company.

It all boils down to the matching of the seller company to the acquirer, the right opportunity, and the synergy that will be realized once the acquisition is made.

How to Value a Private Company?

When valuing private companies, banks use more than one method. No single valuation method can accurately value a private company.

We’ll be discussing three commonly used methods: Trading comparables, Transaction Comparables, and Discounted Cash Flows.

(a) Trading Comparables

Trading Comparables is a valuation method that uses the recent valuation of similar companies in the peer universe of the target business.

Steps in doing Trading Comparables:

1. The first step is to select a peer universe. The peer universe is a listing of all companies that are similar to the target company.

For example, if healthcare company Abbot Laboratories is the target, its most likely peer universe includes similar major pharmaceuticals in the healthcare industry:

2. Second, take out the financial statement data of the peer universe: financial position (balance sheet items), income statement, shares data. You’ll need these data for the computations of multiples.

3. Third, choose the multiples that you will be computing. Following are the usual multiples that are used to value companies:

Common valuation multiples of a Private Company

4. Lastly, estimate the value of the target business based on the HIGH, LOW and AVERAGE multiples of the peer universe.

(b) Transaction Comparables

Transaction Comparables is similar to Trading Comparables. They are similar because they use similar companies as a comparison of valuation.

But, the difference is that instead of the companies per se, transaction comparables use previous M&A transactions targeting similar companies as the basis for valuation.

The rationale behind this is that similar companies would, of course, fetch the same valuation, more or less, with adjustments.

Steps in doing Transaction Comparables:

The process is pretty similar to trading comparables.

1. First, select a universe of M&A transactions whose target involves similar companies as the company being valued.

This will be the peer universe of the target business.

2. Second, get their financial data, balance sheet and income statement items, including shares data.

3. Third, select the multiples to be used. The multiples used for trading comps are also the ones used for transaction comparables.

4. Fourth, estimate the valuation of the target business using the multiples computed. Here’s an example:

If you want a more detailed discussion, I suggest you go see my guide to creating an excel model for precedent transactions.

(c) Discounted Cash Flows

Discounted cash flow is a valuation method which focuses on the private business itself, rather than doing a benchmark with other companies.

Steps in doing a Discounted Cash Flows:

I will be presenting here the general steps for a DCF valuation. If you want a more detailed discussion, I suggest you go see my guide to creating an excel model for discounted cash flows.

1. First, you’ll need to compute the cost of capital which is equal to the weighted average cost of capital.

This is the formula:

Private Company Valuation Formula

2. Second, you’ll need to calculate Stage 1.

How to value a company:

Stage 1 Value is the discounted free cash flows of the period being valued. These free cash flows could either be levered or unlevered.

Unlevered means that interest expenses are not used in the computations. Levered free cash flows are cash flows where interest expenses are deducted.

You must also decide on the discount rate. The discount rate is different for private companies than public companies. The discount rate depends on the buyer or investor.

Analysts usually use unlevered free cash flows under Stage 1.

3. Third, you’ll need to calculate Stage 2.

Stage 2 is equivalent to the Terminal Value at the end of the projected period.

4. Fourth, compute the Enterprise Value, Net Debt, Equity Value, and Diluted EPS.

5. Fifth, compute the Share value per share by dividing the Equity value by Diluted EPS. Compare the Equity value per diluted EPS to the current market value.

If the EV/EPS is lower than the market value, the private company is most likely undervalued. Otherwise, the private company’s shares are overvalued.

Undervalued companies are more likely to be a subject of acquisitions than the companies with overvalued shares.

The Art of Negotiation

Negotiating is more than just mathematics. Actually, it’s more of being mathematics and art.

The negotiation includes non-financial factors. Dealing with private company poses different challenges than when facing public companies.

In deals involving private companies, the focus of negotiations is usually more on a personal level.

Since the transaction is having less public scrutiny and coverage, the communication is done more on an officer to officer, personal to personal, rather than using government agencies or media.

One major issue in dealing with the private company is that if it is family-held, it would disrupt generations of family succession.

Because of this, the seller might request for higher bids than the valuation that came up from normal valuation financial terms.

Another worry for the seller of a family-held business is the financial stability, financial future of his or her family.

He or she is usually the head of the family, so, he or she needs to take into account the financial future of everyone else in the family.

He or she would be conservative in order to avoid mistakes because one mistake might plunge the future of the family into chaos.

A Private company is usually the brainchild of the current owner. Since it is smaller than public companies, and that the owner manages it closely and personally, there would some resentment of letting it go.

There’s a factor of sentimental value. This would make the seller hesitate. This is one of the non-financial factors that could raise the valuation or selling price of the private company.

Since the company is close to the owner, he would like to see it grow it the long-term future.

As such, he would like to see a successor that can do so. Ideally, the successor would come from his family.

But, sometimes external people like external employees, or acquirer private equities would be the successor.

There are cases that the owner would take lower valuation just so that he could ensure that the right successor would be the one who is capable of growing the company into the long-term future.

Pre and Post Money Valuations

How to value a business: In valuing private equities, you would need two types of valuations: pre-money and post-money valuations.

Pre and Post Money Valuations can be used as data for during the negotiation process.

Pre-money valuation is the financial value of the company before the acquisition. On the other hand, post-money valuation is the financial value of the company after the acquisition.

Ways to improve the value of a target company

(a) Reduce leverage

A private company can greatly improve its balance sheet’s appearance by reducing liabilities. Liabilities are not seen as good by acquirers because it would reduce the acquirer’s freedom in terms of choosing the right amount of leveraging of the business.

Reduce the company’s debts, and let the potential acquirer decide on how much leverage the target company needs.

(b) Retain key employees

Key employees are like the hearts of the business. The transition will run more smoothly if the people who know the business in and out will be part of the deal. Succession will be a lot easier for the acquirer.

(c) Have a unique selling proposition

The private company should avoid commoditization of its products.

Commoditization happens when the company’s products are easily copied by competitors to the point that the company’s product no more has the advantage over any other similar products.

It creates too much competition that decreases profit margins even if the revenues increase.

The products should have USPs or unique selling proposition that cannot be easily copied.

(d) Improve the physical appearance of your business

A good ambiance would help increase the financial value of the company. If a company has a crappy office, the first impression of the acquirer would be that the company has crappy operations, and in turn crappy valuations.

A good and clean office and the plant often indicate a good working culture within the company.

(e) Make your business transferable

How do you know if your company is transferable?

Ask yourself, “What will the cash flows of the company without me?” If it’s the same, then it is transferable.

Otherwise, it’s not transferable. With the latter scenario, you will find it harder to get a good valuation.

Next level managers are those that had already a lot of experience with your company but are still young enough to stay with the company for about 10 years or so but under new management.

Evaluate if you already have these next-level managers. If none inside, then consider hiring outsiders that have lots of experience in the industry your company is in.

After reading this blog, have you become interested in Finance, M&A, Investment Banking, Private equity?

If so, you can read these guides on how to start a career in Finance.

Do you have questions relating to private company valuations? Let us know by leaving your comments below!

How to Value a Private Company

Read time: 3-4 minutes

“Strive not to be a success, but rather to be of value.” (Albert Einstein)

Introduction

As a business owner, you probably have a general sense for the range of value for your company based in formal or informal analysis. However, you never truly know what it’s worth until you see what a buyer is willing to put in writing. Therefore, it’s important to understand how investors are likely to approach the valuation exercise so that you can be grounded in reality and ask informed questions of suitors at the appropriate time. The following guide will walk you through the common valuation methods, some key financial information used as inputs to determine value, and some tips to increase your valuation.

Common Business Valuation Methods

A lot of terminology gets thrown around when people start talking about valuing private companies. However, at their core, regardless of what they are called, they are simply ways to put a present value on future cash flows. Here are some of the most common and practical approaches investors will take.

| Description of Each Valuation Method | |

|---|---|

1. Public Comps 1. Public Comps | Within your industry, there are often comparable public companies whose business is similar to yours, though on a larger scale. These public peers, or “comps”, have valuations that are publicly available and can provide guidance around how your business will be valued. Most investors will look to EBITDA and/or Revenue multiples, though there are an array of other ratios that can be analyzed if so inclined. Please remember, though, that a public comp will often be valued at considerably more than a smaller, private peer due to the inherent value of larger scale and the ease with which you can buy and sell public shares. So, in order to determine the value of your smaller, private company, you will typically have to apply a discount to the public comps. |

2. Precedent Transactions 2. Precedent Transactions | The specifics of private transactions in your industry can be hard to come by if they are not disclosed, but in many instances details around the purchase price and implied multiple of EBITDA find their way to the public domain. Further, various entities (e.g. investment banks) that focus on your industry will often publish industry reports that summarize information about comparable private transactions. These reports can give you a good idea what sort of multiple you might fetch for your business. |

3. Returns Modeling 3. Returns Modeling | If you are speaking with a private equity fund or other “financial buyer”, it’s likely that they will do some returns modeling around various growth assumptions for your business. Typically, private equity funds are shooting to double or triple their money over their investment period, and this will impact what they can pay. The most common returns modeling is called an “LBO Model” which forecasts out 5 or so years of performance with certain assumptions regarding the amount and type of debt the buyer would intend to put on the business. |

4. Perception of Value 4. Perception of Value | Experienced investors will often have an intuitive feel for a company’s worth if provided with sufficient information about historical / projected performance. It’s probably discounting the value of this intuition to call it “gut feel”, but veteran investors can often come extremely close to an accurate EBITDA multiple without traditional analysis. Whether they will admit it or not, many investors consult their intuition before other more analytical methodologies. |

Key Financial Information Used to Value a Private Company

If you decide to sell your company, there’s no question that it will ultimately entail the provision of a large amount of data to a potential buyer. However, in the early stages of courtship, the items below are typically sufficient for an investor to arrive at a preliminary valuation range. If you decide to explore discussions with investors, you should make sure you at least have the following items readily available and well organized for when they ask:

Net Working Capital = Current Assets (Excluding Cash) – Current Liabilities (Excluding Debt)

Free Cash Flow = Adjusted EBITDA – CapEx

Tips to Increase Your Valuation

You’ve probably heard many of these before, but it never hurts to refamiliarize yourself with some essential business attributes that will attract investors and support a stronger valuation for your company. You can also download our guide to maximizing your exit valuation here.

Conclusion

We hope you found this guide useful in gaining a better understanding for how professional investors will approach valuing your company. We’ve been investing in privately held companies for nearly 20 years now and would be happy to walk you through our proven process that has resulted in over 20 closed transactions with business owners. We’re here to help, so give us a call to start a conversation.

About ClearLight Partners

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this blog are solely my own and do not necessarily reflect any ClearLight opinion, position, or policy.

Private Company Valuation: Everything You Need To Know

Posted by Valentiam Group on May 26, 2020

Private company valuation poses some specific challenges not encountered in the valuation of publicly-traded companies. Because private companies aren’t publicly traded, they are not required to publicly disclose their financials—and obviously, there are no stock metrics available for comparison to other similar companies. In addition, accounting standards for private companies are often less stringent, so their financial statements may be less standardized and lack the clarity of a public company’s metrics. In family owned and operated businesses, it’s not uncommon for there to be some intermingling of business and personal funds which needs to be resolved before performing the valuation. All of these factors equate to less transparency in the financials of private companies, and make private company valuation more challenging than determining value for a publicly-traded company.

So, how do you determine the value of a private company? Although there are some unique challenges involved, the fundamental approach to valuation is the same. As we explained in a previous article, there are three basic approaches to valuation, and these apply whether the subject company is public or private:

These three approaches align with the Certified Financial Analyst (CFA) valuation designations of multiplier (market approach), present value (income approach), and asset-based (cost approach) valuation. In this article, we’ll examine how you value a private company using each of the three valuation approaches, even without the data you would rely on for valuing a public company.

Need help calculating the value of a private business? Schedule a free discovery call with our valuation experts.

Private Company Valuation Methods

Although information is generally harder to come by for private companies, it is still possible to calculate values by using the information that is available for both the subject business and similar companies—both private and public.

Market Or Multiplier Approach

Because it is difficult to establish private company valuation multiples, the most common approach is to use comparable company analysis (CCA). (Tweet this!) In this approach, the appraiser searches for publicly-traded companies that closely resemble the subject company.

Using this approach, public companies in the same industry of a similar size, age, and growth rate are identified, and averages of their multiples or valuations are calculated for comparison to the subject company. This gives the appraiser an idea of where the subject private company fits within the industry and how it compares to its competitors.

After compiling the price-to-earnings, price-to-sales, price-to-book, and price-to-free cash flow metrics for comparable companies, the EBITDA multiple can be used to help calculate the subject company’s enterprise value. This is calculated by dividing the enterprise value by the subject company’s earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA).

If there are recent acquisitions, mergers, or initial public offerings (IPOs) of stocks for comparable companies in the industry, the information from those transactions can also be used to help estimate the subject company’s value.

The obvious drawback to CCA is that no two firms are exactly the same, so at best these comparisons will provide only an estimate of the subject company’s value. However, these comparisons are useful for determining how the subject company “stacks up” to others in the industry in terms of financial performance.

Income Or Present Value Approach

The basis of the income or present value approach is the premise that the subject company’s current full cash value is equal to the present value of future cash flows it will provide over its remaining economic life.

Estimating the revenue growth of the subject company by averaging the revenue growth rates of the comparable companies and then adjusting for company specific factors is the first step. After estimating revenue growth, expected changes in operating expenses, taxes, and working capital are estimated. Once all of these estimates are completed, free cash flow is calculated, providing the operating cash remaining after the deduction of expenditures. The next step is calculating the average beta (measure of market risk, disregarding debt), tax rates, and debt-to-equity (D/E) ratios of comparable companies, and ultimately, the weighted average cost of capital (WACC).

Calculating The WACC

The cost of capital is the minimum required rate of return market participants demand before they consider making an investment. The cost of capital for a particular investment is the opportunity cost of foregoing the next best alternative investment; this is based on the logic that an investor will not invest in a particular asset if there is a more attractive investment.

In the development of cost of capital, a typical, market-derived capital structure must be established. This capital structure must consider the blend of debt and equity, which the typical buyer would use in purchasing the operating property of a similar company or group of assets. All costs connected with each type of financing within the capital structure must be calculated. Two components make up the costs of financing: the yield for debt and equity, and the cost associated with the issuance of those associated securities.

When applying the income approach, the cash flow expected by the subject company over its life is discounted to its present value equivalent using a rate of return reflecting the relative risk of the asset and taxes, as well as the time value of money. This return, known as the weighted average cost of capital (WACC), is calculated by weighting the required returns on interest-bearing debt and equity capital in proportion to their estimated percentages in the subject company’s expected capital structure.

The general formula for calculating the WACC is:

WACC = (Kd × D%) + (Ke × E%)

For a private company valuation, the cost of debt can be determined by examining the subject company’s credit history and the interest rates being charged to the company. Equity can be estimated using the capital asset pricing model (CAPM). The debt and equity ratings and the cost of capital for comparable companies are also factored into WACC calculations.

After the WACC is calculated and taken into account, we can estimate the value of the subject company in comparison to similar companies.

The main limitation of the income approach in private company valuation is that the calculated value is very sensitive to assumptions about the forecast period, the cost of capital, and the terminal growth rate. Any small changes in these key assumptions will have a material impact on the derived value—and that impact may be substantial. Projections are tricky; assumptions about conditions even several years in the future may or may not hold true. Accordingly, income-based valuations are the most reliable for established businesses with predictable, stable cash flows.

Cost Or Asset-Based Approach

Using the cost approach, we can “re-create” the private subject company from the ground up to estimate its value, calculating the cost to replace the existing assets. The cost approach is based on the principle of substitution—prudent investors will not pay more for an asset than they would pay for a substitute asset of equivalent utility. Once we have assigned replacement costs for all assets, that cost is then adjusted by depreciation to arrive at the current replacement value less depreciation of the subject company.

An advantage to this approach is that it does not rely on comparables, which are likely to differ from the subject company in sometimes substantial ways. It is a very solid valuation method supported by current market costs and conditions. The limitation is that this approach requires a lot of reliable data and calculations; developing this information is very time-consuming.

Any of the three methods can be used to estimate private equity valuation, the cost of equity for a private company, or the valuation of private company shares. The values derived from each approach might be close; in situations involving intangible assets, the best way to value a private company might be to average the values derived from each of the three valuation methods. Whether one approach or an average derived from multiple approaches is used to determine value, there is one additional factor that should be considered when valuing a private company: value discounts.

Applying Discounts

Regardless of the method used for estimating the subject private company’s valuation, several discounts need to be taken into consideration and applied where appropriate:

Although private company valuation presents some challenges not associated with the valuation of publicly-traded companies, the methods for calculating value remain the same. (Tweet this!) While the information needed to estimate value may be more difficult to obtain and require some additional calculations in the selected valuation approach, the principles for establishing value that undergird each approach operate the same way when valuing private businesses as they do when valuing public companies. Due to the reduced transparency of private company financials, however, it may be advisable to use more than one approach to ensure that your estimate of value is accurate and defensible.

Need help establishing a private company valuation?

Valentiam has helped companies in a variety of industries attain much more accurate valuation and property tax assessment of assets. Our valuation and transfer pricing specialists have worked with some of the largest companies in the world. Contact us to see how we can help your company with your valuation and transfer pricing needs.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/mansaPicture_08T-Copy-JuliusMansa-127908fd255745b5886a16fced0cdb7b.jpg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/KSchmitt2019Color-67b7647ab8114851ab0fd161242d5f89.jpg)