How to write a screenplay

How to write a screenplay

How to write a screenplay.

From Hollywood to Bollywood, movies start with screenplays. Movie magic starts with the hard work of crafting movie scripts.

What is a screenplay?

It can take years to make a movie. And just like any other big project, it has to start with an idea. If a movie is like a building, then the screenwriter is the architect. “A movie script is the framework of the building,” says screenwriter Steven Bernstein. “It is your blueprint. It is your plan. All movies, from blockbuster feature films to film school short films, begin with a screenplay, and it’s the single most important document you’ll produce in the entire filmmaking process.”

Script writing is an industry as much as an art or craft. Professional screenwriters are expected to adhere to formatting conventions and industry standards. A member of a production company should be able to pick up a screenplay and immediately know where to find basic things like the title page, name of the screenwriter, and their Writer’s Guild of America (WGA) membership number. They should also be able to easily find a synopsis of the story, the main character, and genre.

Here are the basic elements of screenplays, according to Hollywood pros.

The three-act structure.

Most movie scripts, at least in the English-speaking world, follow a three-act structure.

The page-by-page action of a script should correspond with the minute-by-minute action of a movie. “Each page in script format is about one minute,” says filmmaker Whitney Ingram. “Ninety minutes is 90 pages.” There are occasional exceptions. Dialogue-heavy movies with fast-talking characters might say more than a page a minute, but in general, time and pages line up.

Act one introduces the characters and the central conflict of the story. It’s also where filmmakers need to draw in the audience and get them to care about the movie.

“You’ve got two important functions to begin any movie,” says Bernstein. “That is, hook your audience and get them to care about the characters.” Act one usually includes an inciting incident, in which the main character encounters an obstacle or challenge that they have to overcome and will spend the rest of the movie grappling with.

During act two the characters are enmeshed in the issues, challenges, and conflicts that take up most of the movie. Issues are ongoing but unresolved, and everything is up in the air. “The midpoint is right in the middle of the story when all of the issues have accumulated,” says Bernstein.

Act two is often where characters are at their lowest point, where villains usually get a few wins in, and where things can seem hopeless or unresolvable. Throughout act one and act two, a good screenwriter includes moments and elements that pay off in act three.

Act three sees the characters change, rise to a challenge, and ultimately overcome or succumb to the forces that have descended upon them. Act three is when the characters face the movie’s central challenge. It’s when heroes storm the castle, detectives crack cases, and romantic leads give passionate speeches confessing their love. It’s also where other, smaller seeds that you’ve planted throughout the screenplay pay off.

“The key to good screenplays is that you set up all these little nuggets or gems that are paid off in the third act,” says Bernstein.

Beyond the three-act structure

The three-act structure is a guideline and a convention, not a rule. Many filmmakers go beyond it and tell stories that do not have clear first, second, or third acts, or even clear characters or conflict. “I’d argue that the function of art is to give observers new eyes to see the world,” says Bernstein. “You should be free of mind in your approach not only to content, but also to form.” It is possible to write an unconventional screenplay, but if you do, be intentional.

Screenwriting terms.

Screenwriting, like every profession, has its own specialized collection of terminology, slang, industry terms, and jargon. Here are a few terms you might find helpful:

Every scene in a script begins with a slugline — also known as a scene heading — a short description of where the scene takes place. Sluglines always indicate whether or not a scene is interior or exterior, where it is exactly, and time of day. A scene that takes place on Tatooine, for instance, would begin with a slugline like:

EXT – TATOOINE – DAY

A slugline inside the Death Star would look like:

INT – DEATH STAR – NIGHT

Action lines are simple and declarative, and after you get them out of the way you can start describing the setting with action lines, which might sound like:

“Fade in on a desolate desert planet. We see R2-D2 and C3PO walking across the seemingly endless dunes.”

Action lines give readers an idea of what should be happening in the scene, and what the characters are doing when we see them.

Dialogue usually takes up most of a movie script. Dialogue has the character’s name above it and is usually written without quotation marks. It’s also written with large margins or is centered to set it apart on the page from action lines and other copy. For example, Han Solo bragging about the speed of his ship would be:

You’ve never heard of the Millennium Falcon? It’s the ship that made the Kessel Run in less than twelve parsecs!

Sometimes dialogue contains special instructions or notes in parentheses, like if a character is offscreen or doing a voiceover. Obi-Wan telling Luke to turn off his targeting computer could look like:

Use the Force, Luke.

Important events or moments in a screenplay are known as beats. “A story beat is some significant moment,” says Bernstein. “It’s when things can turn in some different direction.” Examples are a detective finding an important clue, an action hero getting injured, or the leads in a romantic comedy having a conflict or misunderstanding that drives them apart.

“The logline is the summation of the story in one sentence,” says Bernstein. A logline is often the first thing studio decision-makers hear about a movie, and screenwriters often start their screenwriting process with a logline and go from there. However, it’s always possible to change a logline after you’ve written a final draft.

Loglines often contain a hook. “Usually there’s some kind of irony in the logline,” says Ingram. That irony usually shows off how the film is different or unusual. “I’ve never known a film to sell on a logline,” says Bernstein, “except maybe Snakes on a Plane.”

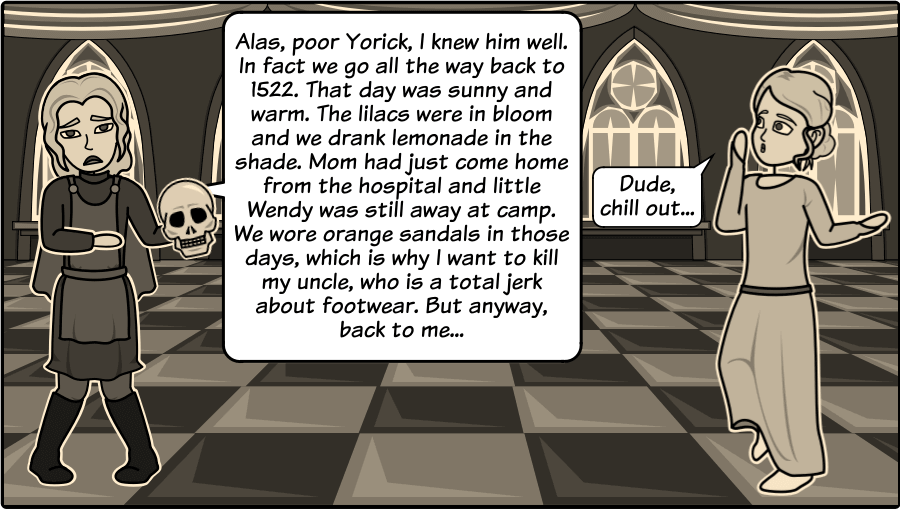

Elevator pitches are a bit longer than loglines, but still short. An elevator pitch is a short description or synopsis of a project that usually takes up about 30 seconds, the length of an elevator ride. The elevator pitch for Hamlet would sound something like:

“The king dies, and his brother assumes the throne. The dead king’s son suspects that his father was murdered, and works to bring down his uncle.”

Obviously this leaves a lot out, but the focus is on describing the movie quickly.

A treatment is a written document that outlines the story and main ideas of a movie. It’s usually written in the present tense and sticks to the main story beats and big moments of the film. Treatments are usually much shorter than screenplays, but they can sometimes be up to 60 pages or so.

Once a film is in production, a shooting script is created. This version of the screenplay numbers the scenes to help all departments coordinate their work — especially helpful as most films are shot out of order (not chronologically based on the events of the screenplay).

For example, if a movie has several separate scenes that take place in a casino, the shooting script uses numbers to note that all of those scenes can be filmed in the same block of time, even if they appear at different times in the movie.

Colored pages are used in shooting scripts to help teams ensure they are working with the most recent version. Any updates are added to shooting scripts in a new color.

Movie magic on the page.

Film production is a long process that can take years, and it often involves hundreds if not thousands of dedicated professionals. But every blockbuster starts with a movie idea from the script writer. A film script is a guide to collective projects, like a blueprint for a building — or a treasure map for a voyage of discovery.

Screenwriting 101: 7 Basic Steps to Writing a Screenplay

Writing a screenplay is an extremely rewarding process, but it’s not an easy task. It takes a serious amount of time and dedication to develop a good screenplay, and if your goal is to sell it, completing a first draft is only the beginning. You’ll have to refine the story, often with several more drafts, get an agent, submit your script to studios and producers, and have someone like it enough to risk a substantial amount of money to buy it. Unless, of course, you’re planning to finance and produce it yourself.

Each year, the major Hollywood studios purchase a combined 100-200 original screenplays. When you consider that somewhere between 25,000 and 50,000 new screenplays are registered with the WGA every year, it’s easy to see how difficult the task actually is. But, don’t be discouraged. Most people don’t invest enough time learning how to develop a good screenplay; they just try and write one. By dedicating yourself to the craft, your screenplays will start out well ahead of the pack. There are a few steps to follow when developing and writing your screenplay. Remember, though, there are no real rules, so they can happen in any order, or not at all. It’s up to the story, and ultimately you.

Step 1: Craft a Logline

A logline is a brief summary of your story, usually no more than a single sentence, that describes the protagonists and their goal, as well as the antagonists and their conflict. The protagonist is the hero/main character of the story, while the antagonist is the villain/bad guy/opposing force. The goal of a logline is to convey both the premise of your story and its emotional undertones. What is the story about? What is the style? How does it feel?

In the old days, the logline was printed on the spine of the screenplay. This allowed producers to get a quick feel for the story, so they could decide whether to invest the time into reading it or not. Today, the logline serves the same purpose, although it’s usually communicated verbally, or included with a treatment.

Step 2: Write a Treatment

A treatment is a longer 2-5 page summary that includes the title of your screenplay, the logline, a list of main characters, and a short synopsis. Like loglines, treatments are mostly used for marketing purposes. A producer may read a treatment first before deciding if the script is worth their time.

The synopsis should highlight the main beats and turning points of your story. Anyone who reads it should get a very good idea of the story, the characters, and the style. They should learn enough to feel empathy for the characters and want to follow them on their journey to see how it plays out. Writing a treatment also gives you the opportunity to view your story as a whole and see how it reads on the page, and it can help you understand what’s working versus what needs work before you dive into the details of writing each scene. Since your treatment will be used to market your screenplay, be sure to include your name and contact info, too.

Step 3: Develop Your Characters

Think about the story you want to tell. What’s it about? Do you know the theme yet? Create characters who will contrast the central question, and who will have to undergo a major transformation to answer it. There are plenty of character profile worksheets online that can be helpful in bringing your characters personalities to life. Two that I’ve found to be helpful are here and here.

The most important thing when developing your characters is that you make them empathetic and interesting. Even the bad guy should have a reason he’s bad, although it may be unjustified.

Step 4: Plot and Outline

Break your story down into its narrative-arc components and map out every scene beat by beat. I know a number of writers who use flash cards or notebooks for this. Personally, I use Trello for outlining my screenplays. I create a board for each script, then I make a list for each of the narrative-arc components, with a card for each scene. On each card, I make a checklist of the story beats and write notes about the characters or plot.

Do whatever works for you. The goal is to plot out your story. The more detailed you make your outline, the less time you’ll waste down the road. As you plot, keep in mind that tension drives a story. Building and releasing tension is key to keeping the audience engaged and driving the story forward. When hope is faced with fear, tension is created. This is what forces the hero to change.

Step 5: Write a First Draft

Using your outline as a map, write your script scene by scene, including the dialogue and descriptive action. The first ten pages of a screenplay are the most critical. A reader or producer usually has a ton of scripts flying across their desk and they don’t have time to read them all. They’ll give a screenplay ten pages to pull them in. If the script has interesting characters and the proper structure elements, they’ll likely continue reading. If not, it’s going in the trash.

The screenplay is a unique format of writing. While it’s true that there are a number of elements common to any story regardless of medium, screenwriting is different in that every word of descriptive action must be written in present tense and describe something the audience can see or hear.

Although typewriters and word processors work just fine, I suggest investing in software that will do the formatting for you. Hollywood follows a fairly strict format when it comes to screenplays. While this can cause quite a bit of confusion, it was more of a problem in the past. Modern screenwriting software makes it a very easy process. The most commonly used apps include Final Draft, Movie Magic Screenwriter, and Adobe Story.

Don’t stop and go back to fix dialogue or update action description until you’ve written the screenplay all the way through. Then you can go back through it, tear it apart, and rebuild it. Don’t be too self-critical during the first draft. Just write.

Step 6: Step Back and Take a Break

Once you finish a first draft, it’s a great idea to relax a bit and take your mind off of it. That way when you finally do come back to it, you can read it with a fresh set of eyes.

Step 7: Rewrite

Now that you have a completed draft, you have a much better picture of your story as a whole. Go back and refine the action, tighten the dialogue, and edit the script. Chances are you will have to do this more than once. When creating a final version, using more white space on your pages is better. It’s easier to read and seems quicker to get through. When a producer has to read multiple scripts a day, it’s discouraging to see a script filled with pages of dense action description and long monologues.

Overall, writing a screenplay is a difficult task — one that takes sacrifice and a dedication to the craft. In the end, it’s a rewarding process, in which you get to create characters and watch them come to life as they make choices to navigate the obstacle course you’ve placed before them. Take some time to study the craft, and your script will be done in no time.

For more in-depth tips on learning to write a screenplay, there are a handful of books considered by most industry professionals to be must-reads for any aspiring screenwriter. Each one offers valuable insight into a different aspect of developing a story, creating interesting characters, and crafting a thoughtfully motivated screenplay. These include Screenplay by Syd Field, Story by Robert McKee, The Art of Dramatic Writing by Lajos Egri, and Save the Cat by Blake Snyder.

How to Write a Properly Formatted Screenplay

This article was co-authored by Stephanie Wong Ken, MFA. Stephanie Wong Ken is a writer based in Canada. Stephanie’s writing has appeared in Joyland, Catapult, Pithead Chapel, Cosmonaut’s Avenue, and other publications. She holds an MFA in Fiction and Creative Writing from Portland State University.

This article has been viewed 50,597 times.

Maybe you have a great idea for a screenplay, but as you start writing, you realize you are not sure how to format your screenplay properly. There are strict rules when it comes to formatting a screenplay, from margin size to commonly used terms, harkening back to the days of writing scripts on typewriters. You can make sure your screenplay is properly formatted by putting in screenplay terms and notations as well as making sure the screenplay appears correctly on the page. You can also try using screenwriting software to help you format your screenplay.

Sample Script and Outline

Support wikiHow and unlock all samples.

Support wikiHow and unlock all samples.

BARB

What are you doing out so late at night, Max?

MAX

Oh you know, couldn’t sleep.

BARB

Nightmares, again?

MAX

(agitated) No. (pause) I mean, good night.

BARB (O.S.)

Good night, Max.

BARB

I just don’t understand what he was doing out so late. He looked scared of something, like he had seen a ghost.

(MORE)

How to write a Screenplay

Creating Movie Scripts

In the beginning, there is always the idea… and then there is a wall, a great white wall. Your own personal Moby Dick, an impossible climb that you must make if your idea is ever to see the light of day. And that wall is the blank page. Whether you write on paper or on a screen, that empty space in need of words is a daunting and intimidating task, even for the most seasoned of professionals.

When it comes to filmmaking, the screenplay is the absolute first step which must be taken. Composing a complete script that works is the foundation upon which your project will be built. You have to get it right or it all falls down. Now that blank screen has a whole film riding on it. No pressure, right?

Here’s the good news: you can totally do this. It’s hard work, and you have to follow formats, structure and plenty of rules, but it’s not as impossible as it might look in the beginning. Below I offer a mix of philosophical, mechanical, and logistical approaches to getting a screenplay done. This isn’t just about physically producing the document. It’s about pulling the best work out of yourself that you can. And more importantly – it’s about reaching readers and audience.

Write Every Single Day

Readers are the people you need to believe in your vision. They are the investors and production people you must convert into patrons and partners. You must hook them with a read that flows easily while striking deep into their imaginations. Convert them and your film gets made.

But film audiences don’t read screenplays – they watch movies. Your concoction must also be able to materialize onto the screen. It’s quite a bit of magic you have to pull off: the written word transforming into the audiovisual execution. So put on your wizard hat and learn as many tricks as you can.

This doesn’t just apply to screenplays, but to any kind of writing. A completed work is an elusive animal living within yourself which does not want to be captured. It comes from the place inside of yourself that dislikes the light of day. Consider this a no-kill hunt: to track down your quarry, you cannot lose its trail. Give it some sweat without fail at least one hour for every 24. Accept this reality before you learn the first thing about screenplays.

Organize the Key Elements

Now that you’ve committed to the writing routine, it’s time to get to your awesome idea. Before writing a word of the script, capture the essence of the screenplay – story, plot and characters – with these three essential tools:

Story Outline

This should be short, no more than a couple of pages. Here you describe in broad strokes what happens in your tale. It’s a big picture map of the journey ahead, serving as a compass to keep you on track with the course of the script. Set up the circumstances. Describe the challenges to be faced. Explain the resolution to it all. Short, sweet, simple.

Scene-by-Scene Plotting

Create a series of notes – digital or index cards – and write down what happens in each scene of your film on each note. Individual scene notes represent 3-4 minutes of screen time. Put 30 of these notes together, you reach standard feature film lengths (90-120 minutes). Adjust this formula for shorter works (commercials, YouTube, etc.). Be detailed, use bullet points, lists, and other tricks to cram information in. From here will issue your screenplay.

Character Bible

Write up a list of your characters. Main characters should have a few paragraphs about who they are, where they’ve been, and what motivates them. Secondary characters don’t need as much info. Even characters who have just one line should be named. This not only keeps tabs on the population of your screenplay’s world, it makes them real. Don’t be afraid to add or alter characters on the way – they tend to surprise writers with lives of their own.

Check out Storyboard That’s articles on Narrative Structures and Character Maps for helpful info.

Learn the Form

This is the part that will feel like school and there’s no way around it. If you want your work to be read, it MUST be written in the standardized form. That means following margins, using film terms, the 3-act structure, and even spelling (for real). The good news is that several excellent screenwriting programs do a lot of this automatically for you. Nevertheless, the writer needs to understand these mechanics if she is to construct a script. The industry standard on the subject is Syd Field’s The Foundations of Screenwriting. Seek it out, read it. And remember: one page in the format equals one minute of film time. Feature scripts need to be 90-120 pages long.

You Have Five Pages to Win Them Over

Here you are, at the start of your script, ready to roll. Remember how I said earlier you have to hook the reader? Well that needs to happen fast. In the real world, people who read scripts professionally are sick of reading scripts. If they aren’t interested in literally the first five pages, they will throw your work in the trash and move on to the next. I know – that’s harsh. But it’s the way it is. Even friends and family will lose interest quickly. So make sure everything that’s awesome about your script makes a big splash right off the bat.

This Isn’t a Book, It’s an Instruction Manual

One of the biggest mistakes screenwriters make is over-explaining things. The fear is that unless every thought, every action, every moment is described in great detail, the reader won’t “get it.” But that’s all wrong. The art of filmmaking is in the final execution. A screenplay should only explain what NEEDS to be seen and heard on the screen. For example, you can’t “see” a character’s thoughts, so you shouldn’t be explaining them on the page. And when you describe a scene, don’t go crazy. A prose book is forced to use words to show us a place, film is not. Give the production some room to find its own look and spare the poor reader’s eyes. That doesn’t mean you skip the important stuff, though. Spell those things our clearly and concisely. Remember – just because you wrote this doesn’t mean you’re directing it. Always write as if someone else will have only your script to know how to make the film. It really is a set of instructions as much as its own work of art.

A Word on Dialogue

Dialogue can be the most fun to write in a screenplay. Then writers get carried away, giving every character Hamlet speeches. But nobody in real life explains their motivations all day long. Film is a visual medium first. Save dialogue for what matters – moving the story forward and revealing the characters’ inner selves. Avoid expository speeches. Keep things punchy and short. A close up on an actor can say much more than three pages of soliloquy. Let the camera do some of the talking, or the weather, or even a simple gesture. Hold on to those killer lines for the right moment, and don’t let them get lost in a sea of babble.

Filling Up on Emptiness

There’s an old screenwriting trick known as “white spacing.” This means not having lots of words on lots of pages and being sure to leave a lot of empty space. Anytime a script has large clumps of description or dialogue, it usually means trouble. We already know readers have short attention spans. And the writer needs to trust cast and crew to add to her initial vision. So, don’t clog up your script. Economize your words. Say more with less. It not only makes for an easier read, it opens up room for things to happen cinematically.

Let Go and Let the Story Control You

At some point, after learning all the rules, after outlining the story and plot, after meeting your characters – forget everything. Let your fingers do the talking. Trust in your tale and let your characters speak for themselves. Yes, there are goals you must direct the action towards, things people must say. But the stories and the people in them have more to tell you than you might know. Let your creation use you as a host. Unleash the subconscious with surrender. I know it sounds corny, but let me tell you, being possessed by a story is a powerful feeling.

Exercise

Don’t forget that your writer’s mind is attached to a writer’s body: fingers, spines, and of course, butts. Don’t fool yourself – just because you’re sitting around writing all day doesn’t mean it’s not physical. Carpal tunnel syndrome, cramps, back pain, and much more plague writers. Keep them muscles strong! Do some light weights or pushups. Take walks to get leg blood flowing. Stretch out. Maintain proper posture. All this will strengthen your insides to endure the long hours you will need to abuse your hands. Not only that, but it will feed your brain and soul with endorphins and psychological release. Take care of your tools.

Read, Edit, Repeat

You’re done with your first draft of your screenplay? Awesome! You’ve probably got two or three more to go. Read your work slowly, patiently. Check grammar and spelling like a hawk. Challenge yourself with questions. Does the story make sense? Are these jokes funny? Will people buy this plot twist? And get other people to read it. Ask them to be merciless and provide lots and lots of notes. Consider all suggestions seriously. The truth might hurt, but friends and peers can often see things you don’t see. Be strong – not everyone will get what you are doing. But comparing notes from several parties can reveal patterns you didn’t know were there. Finally, if you’re at your fifth draft or so, stop where you are. You should know if it’s pitchable or not by then. Some scripts may not work – but that’s part of the process. Keep going on the next one. You’ll get better. I promise.

At the end of the day, whether you wrote the best damn thing ever or end up unsatisfied with your final product – congratulations! You finished a screenplay! Do you have any idea how few people actually do that? Take pride in the accomplishment, no matter what the outcome. It’s a great skill you have taken on and one which will always teach you about film, about writing and about yourself.

There’s lot of other “rules”, trick, and devices to get that screenplay out of you. The ones I offer here are just the ones I think are the most important. They should at least get you off to a good start. Use them as markings on your own path to writing your script. And please try to enjoy the adventure. It can take you anywhere you can imagine… literally.

About the Author

How to Write a Screenplay: Script Writing in 15 Steps

In order to understand how to write a script and perfect a screenwriting format, you will need a little screenplay writing know-how. This know-how will guide your steps as you set out on your script adventure to Mordor, taking the red pill or setting sail for Pandora.

Naturally, you will want to write your script well. In this guide, I will be explaining both how to write a screenplay and the correct way to format your screenplay, step by step: covering each aspect of screenwriting and how to do it well.

So if this feels a little overwhelming, don’t worry, you’re in good hands. You can try out each part at your own pace until you feel you’ve got it.

The following 15 steps will help you with all facets of your screenplay:

Whether you are writing a screenplay for the first time or the tenth time, it never hurts to use a good template. You can find many screenplay format templates in Squibler for all genres.

A template helps you stay on track and ensures you don’t miss anything. It makes these 11 steps even easier to work with:

What is the Difference Between a Script and a Screenplay?

There isn’t a clear-cut difference between a script and a screenplay. Both are often used interchangeably. However, every screenplay is a script, but every script is not a screenplay. A screenplay is a type of the broader term, script.

Even though not many differentiate between the two, in filmmaking, the screenplay is regarded as a preproduction draft (a writer’s original draft) which acts as a guide for directors. It includes minor details about the set, such as camera angles, close ups, and lighting – basically it’s a director’s tool.

On the other hand, a script is a concise version of a screenplay used during production/post-production. It removes the unnecessary details about the stage direction (such as time and place, other formatting, etc.), and helps actors focus on their dialogue/action delivery, making it an actor’s tool.

How Do You Start Writing a Screenplay?

The first step can be the hardest. However, what’s stopping you from working on your first draft is the fear of not being good enough. The only way to get rid of that fear is to confront it with self-confidence, and that comes from knowing the basics of writing screenplays.

To begin with, screenplays are a distinct form of writing. Their structuring matters, hence knowing the proper format is important, and organizing your writing from the start will save you and everyone else involved a lot of time.

Therefore, you need to read at least one book or watch a 101 lesson on screenplay writing. Check out the plethora of online guides and note down all the screenwriting tips while you’re at it.

Subsequently, read at least one award-winning screenplay related to your genre of interest. Try to make notes as you read through them – what makes them great, how they’re different from an average screenplay, what you can learn from them, etc.

Furthermore, make sure that you at least have a logline for your screenplay, if not a plot.

Finally, start working on your first draft. The trick is to not worry about killer action lines, white spaces, page counts, and other technical headaches. This is not the time to edit and perfect, anything that remotely looks like a screenplay suffices.

You can worry about formatting later (there are software and templates that can help with that).

How to Write a Screenplay

If you are looking up how to write a screenplay on the web, then the likelihood is you’ve just started the writing process. Either that, or you have only just gotten serious about selling your script.

A few rules of thumb to follow when writing a screenplay:

In the following I will go into a lot more detail about most of the points I just made. The above are the very basics and will give you a jump start if you’re itching to get down your first scene. For a more comprehensive and sustainable way of writing, read on.

1. Spec and Shooting Scripts to Write a Screenplay

Before you even think about the format make sure you know what your script is for.

Spec scripts are written on speculation. You are not being paid to write it, but are doing so in the hopes that someone will buy it. It’s therefore extremely important to follow already established screenplay writing rules.

A shooting script has already been purchased and is therefore a production script, ready to be used on set. It has extra technical notes on shots, cuts, edits, etc, that you should never find in a spec script.

2. Why Using a Standard Format Matters

Want to know how to write a script? Start by formatting it properly.

If you are only writing for fun, the script format isn’t a big deal, right? Wrong. Using the standard format matters, because it will make filming easier. It will also look more impressive and you will have all of the tools and knowledge you need to write every part of a script.

But it’s not necessary. You can quite happily get along without it, especially if you’re making a short and small production between friends. You can write well without it (especially if you are going to make a film in your own backyard with an iPhone). So, why bother?

Well, several reasons:

It could be the most wonderful work of art ever created, and it would already be in the trash. This is because a lack of formatting implies negligence on the part of the writer. ‘If you can’t even format it right,’ they will think, ‘then what is the writing going to be like?’

And I hate to say it, but they have a point. If you’re really serious about screenwriting, knowing how to format will help you to look professional. It’s that simple.

It doesn’t mean your script will be sold. But it at least gives you a chance.

Recommended Reading

Naturally, reading this article will help. But reading more about how to write a screenplay successfully will always put you at an advantage. So do that.

To start with, I would recommend Save the Cat by Blake Snyder. This witty book has been read by pretty much anyone who wants to write for the big screen (the tagline being ‘the last book on screenwriting you’ll ever need’).

Don’t believe the tagline. You’ll want to read more if you’re serious about this. And consume as many films as you possibly can. (Not the worst homework in the world.)

Another book I would recommend is The Hero’s Journey or The Hero with a Thousand Faces by Joseph Campbell. Both are great for helping to understand story and characters archetypes, which will play a role in your writing, whether you like it or not.

There are other theories on story, Campbell’s is just the classic text that influenced big hits such as Star Wars, The Matrix, The Lion King, etc.

The Screenwriter’s Bible by David Trottier is another book that everyone and his mum have read in preparation for writing a script.

If you’re writing a romantic comedy or any other genre, you’ll naturally want to hone in on that and become more knowledgable about that, as well as film generally. Take an afternoon off to watch Love Actually, go on, I dare you.

Read for your appropriate field or subject of interest.

Go on a course led by is a professional screenwriter and take what you can from their pool of knowledge.

There comes a point where the only thing that will really make a difference to your writing, is to write.

The Process of Script Writing

Writing should be fun. But it is not always. It can be frustrating and exasperating. But the thirst to do it is what draws you back to it. Hopefully. If not, consider doing something else with your time!

The main principle to bear in mind is to be able to have a consistent practice. Write in your own way. Write when works for you. Maybe you’re a planner, or maybe you like the plot to unfold. Whichever it is, you will need a lot of drafts written, a lot of scenes cut and a lot of edits and rewrites.

If your writing sucks, then great! As long as you’re writing, that’s all that matters. The more you write, naturally, the more the quality of your work will improve.

Stay humble and don’t aim for anything too wonderful. If you get stuck, go for a walk or write that scene that you really always wanted to write. If you’ve already written it, rewrite it. It couldn’t hurt.

Creating an appealing hero/ heroine is an important part of the writing process and will inevitably make or break your screenplay.

No one is going to watch if they don’t care for the main character, no matter how compelling your idea.

A logline is just as important. If you don’t know what your script is about, how are you ever going to be able to sell it? The essence of a script should be able to be diluted down to 20-25 words. And it should make anyone who hears it say something along the lines of ‘huh, that’s interesting.’ If the ‘what’s it all about’ doesn’t grip you with anticipation and fill you with ideas, then perhaps you need to rethink what you want to write about.

3. Plotting

Planning your script can be challenging. It will make writing your scenes and dialogue immeasurably easier to write once it is done. You do not have to plan. It’s just good to note that you’re making things harder for yourself if you don’t.

During the experimantation phase, when you might not have the plot set out, you can start by writing scenes on cards and moving them around to see how the beast (aka your film) interacts with itself and how moving one scene from the middle to the beginning (as happened in Bridget Jones’ Diary) can completely change the whole feel of the thing.

Many writers use certain software that can help with the structural elements of creating story (see ‘choosing the right software’ for more info). Otherwise, buy yourself a cheap white board and write out ideas for your storyboard on there.

Whatever works best for you.

4. Editing and Fluid Movement

Bear in mind that a script is one of the most fluid pieces of writing out there. Possibly THE most. It is living breathing and alive. This is because it never stops evolving throughout the whole process.

You will go through copious amounts of edits. First, to get it good. Second, so that your editor believes it’s good. Next, if it’s sold, there might be things the industry players want changing.

Once it’s on set, it is changed for that purpose. And then there’s that line that the actor just can’t say. And then that scene that is cut during the video editing process.

It’s exciting. It can also be heartbreaking. But at least it’s your damn script. And that’s something to scream about.

5. Don’t Try to Be Original, Actually Be Original

Don’t try to reinvent the wheel. One mistake that new writers will be tempted to make is, once they know the typical structure of the genre of their choice, they want to break all of the rules.

You can do this, but it might not serve in your favor. Unless you have a really, I mean, really good reason for it.

The originality of your writing should come out/be evident in what you write within those already well-defined structures. That is what will make you shine. And will maintain a sheen of professionalism needed to be considered amongst the best scripts.

6. Choose a Script Writing Software

There is quite a range of screenwriting software out there to choose from. You can choose anything, from typing it out old-school on a typewriter (very cool choice, but a hell of a phaff these days) to using the most up to date and easily accessible software available for download online.

Novelists keep and maintain their work through software like Squibler. It allows you to organize your notes and to plot your novel easily. Software that is designed to help you to write any kind of art can help to take some of the stress out of planning it all yourself, without any structure.

Screenwriting software is similarly made to help you to plot your script. The main consideration will be what you’re writing your script for. If it’s for an indie production and you don’t want to spend much (or any) money, then there are plenty of budget resources out there. These are ideal for the newbie screenwriter not quite ready to submit their script (Amazon’s Storywriter, WriterDuet, Celtx, Fade In).

The great thing about using these programs is they all have a basic screenplay format template, already formatted and ready for you to use. So you don’t have to worry about pinickitty spacing. You only have to remember which section of the script you are writing at any one moment (dialogue, action, parentheticals, etc.).

You can also use a Word or Office document and work out all of the correct spacing. But I honestly have no idea why you would, unless you get a kick out of (measurements and) the anatomy of a standard script format.

If you are ready to start selling your script (or seriously intend to in the future), then I would advise investing in one of the more upmarket and slightly more expensive versions of this software (Final Draft, Magic Movie Screenwriter). They are also great if you have the money and think you could really benefit from their useful features, such as: index cards, storyboards, storymaps, breakdown reports, call sheets and/or professionally authored templates.

Final Draft is the industry standard, but there are others (Magic Movie Screenwriter, Celtx) that I’m sure work just as well. If you want to be on the safe side, it’s Final Draft all the way. (Note: this is not an endorsement, Final Draft file and PDF formats are the standards to send to industry professionals.)

If you haven’t already, go and install one of these software and come back so I can explain what to do with them.

7. Front Page/Fly Page

To start, this one is an easy page to write. As you can see from the script template below, it should be simple, elegant and minimalist. All writing should be in courier, size 12. The first page is never numbered. You want your title in the center of the page in all caps, the word ‘by’ a few lines down, and then your name.

Flush right (or left) at the bottom of the page, you want to put your contact details This is so that you can easily be contacted should someone want to buy your script.

The title should express the essence or meaning of your work in just a few words. Often writers will wait until they have completely finished before choosing a title. That is because you are more likely to know its main message and all underlying themes by the time you have worked on it extensively.

For now, just pick one. You can always change it.

8. First Page

Every first page of a script starts with the words FADE IN: in the top right-hand corner. The last two words of any script will similarly be FADE OUT:

9. Slug Line/Scene Heading

The point of a slug line is to let the director, crew and actors know where and when the scenes will be set and shot. It is mostly there for practical reasons. This is (therefore) not the place to get poetic with your writing.

A typical script format will require many sluglines. Each should include three pieces of information:

Whether it is to be shot inside or outside (INT./EXT.),

where it is to be shot (e.g. JAIMIE’S BEDROOM)

and the time (DAY/NIGHT/SUNSET) (You don’t need to be too specific about the time of day, this simply helps the lighting crew know what they are doing.)

You might want to add on MOVING as a fourth piece of information, if your character is in a car, or on top of a train, for example. Another piece of information to include could be LATER (if you are in the same place but time has passed) or RESUMING (if you are continuing a scene you had already started previously).

10. Action

Action is the section where you can really let your writing shine. This is your chance to capture the reader’s imagination.

The key here is to succinctly describe what is happening: choose your words carefully so you can get to the point as quickly as possible. Here you want to set the scene, give a little taste of what your characters are like and show what they are doing.

Action must be written in the present tense. It always comes before dialogue and make sure to mention the characters in the scene. The first time you mention their names, you will want to CAPITALISE them. From then on, they can remain in lower case during the action sections.

You can also capitalize sound effects, important props or details (e.g. he held golden KEYS or the SMOKE snuck under the door)

11. Dialogue

Dialogue is also pretty straightforward. Once you have succinctly written your action section, the dialogue will inevitably follow.

To write dialogue in a classic screenplay format, you will need; your character’s name, centered in block capitals; beneath it, slightly to the left, you will want to write the actual dialogue.

When you want to add dialogue that is offscreen, write (O.S.) next to the character’s name (write (OS) for when they return on screen). For a voiceover, write (V.O.). When your character is talking into a phone, predictably, write (INTO PHONE).

NB The difference between offscreen dialogue and a voiceover is that the character is involved in the action, but can’t be seen. A voiceover is a narration. O.S. dialogue, however, is used when they are about to appear onscreen.

A quick tip for character names is to make them each start with different letters. This is because often screenwriting software will handily suggest names for you, once you have started writing dialogue. If they have different letters to start each (e.g. Jaimie and Diane), then you won’t have to go through a long list of names and can save time.

Some writers find writing natural-sounding dialogue comes easier to them than others. The key here is to write a lot, to the point where you can feel the rhythm of the text flowing more easily. If your dialogue surprises you or fills you with a certain emotion, that is a good sign, too. What you don’t ever want to feel when writing dialogue, is bored. If you do, then the reader is sure to also feel bored. So keep writing until you break through to that interests you.

A deep knowledge of your characters helps when writing realistic or moving speech. Make sure that the scene is always moving forward, that you have an endpoint or destination in mind for each scene, that there is enough conflict, and if a line does not create some form of conflict, then it should reveal something to us about your characters, and why we should care about them.

What Dialogue and Action Should Be

Ideally, your action and dialogue will flow freely, working together to give us an understanding of what is happening, without your having to spell it out. You won’t have to say your character is sad, because they will be crying. Or better yet, they will be smiling.

One of my favorite examples of this subtle use of action is in the film, Les Choristes. (Spoiler alert.) The protagonist has just been dumped. He is sitting in a café, his love is walking away from him to her new life, with a new guy. A stranger walks up to him and asks if the chair where she had been sitting, is taken. And then the stranger walks off with it.

This is such a subtle and simple way of showing that the protagonist does not have anyone in his life to share the table with. These little interactions can say a lot, without the character ever needing to say a word.

Dialogue and action tell us who your character is, so you need to know what your character is saying (or not saying) with each line. And make sure that every word written is either pushing the plot forward, creating conflict or showing their growth or uniqueness as a character.

Never have a conversation for conversation’s sake. It is boring and will result in your reader losing interest. Everything MUST have a reason for being there. In real life, people have boring conversations. On screen, they do not.

12. Parentheticals

To specify how a character speaks, add a parenthetical. They are placed underneath the name, right before the dialogue starts. These might include (angry) or (calm). Only add them where absolutely necessary as their mood should be obvious from the dialogue.

So unless their mood directly opposes what they are saying, don’t use them.

13. Cut To:

Transitions signify the way a new scene just began. They usually are placed to the far right of the page at the beginning of a scene. They are mostly a note for the editor of the film.

While you may find a script template or two online filled with transitions, the likelihood is that they were either written by an already successful writer who can do whatever they want, or you’re looking at a shooting script. So use them only when absolutely necessary.

Other examples of transitions include:

14. Chyrons / Title Cards

A chyron is basically a title that lets your audience know some basic information. It is useful for specifying a time and/or place. It is a standard part of your screenplay format.

Write OVER BLACK (or whatever color you want, although black keeps it simple and is typically what is used) and then CHYRON: ‘2:45 PM’ or TITLE CARD: ‘2:45 PM’

Close the sequence with TITLE DISAPPEARS.

15. Montage

Write BEGIN MONTAGE:

Another time montage can be useful is during the midpoint of the film, or when they are in the most difficulty- where the character is considering who they really are, feeling pretty crummy about what has happened. We see this in The Devil Wears Prada as Andy is walking the streets melancholically, considering her situation.

A montage sequence works well in these moments because it gets across a lot of information pretty quickly.

Can Anyone Write a Screenplay?

Anyone can write a screenplay after reading a few good books on screenwriting, memorizing the best screenplays, and bingeing on a few cinematic hits.

However, if you’re wondering, ‘can I make it to Hollywood?’- the answer is it depends.

There’s no questioning that a screenwriter needs talent and an active imagination, but it’s your grit that will help you get where you want to be. Screenwriting is an art that only gets perfected with practice, perseverance, and time.

Having said that, there’s no harm in writing screenplays for fun. And yes, anyone can do that.

Let’s Write a Script

So, that’s it for your guide on how to write a script successfully. Now all that is left is to get started! Hopefully, a few of the tips in this guide will have brought you closer to starting your FADE IN: and beginning to create the images and ideas in your head.

And you owe it to us and yourself, to do that. To follow your bliss. Because the world likely needs your ideas. The world needs your story, your journey. We never tire of our thirst for good stories. So what are you waiting for?

TABLE OF CONTENTS

What is the Difference Between a Script and a Screenplay?