How to write a story

How to write a story

How to Write a Short Story in 6 Simple Steps

Writing a short novel can be a challenge: in the space of a few pages you’ll have to develop characters, build tension up to a climax, and resolve the main conflict.

To help you with the process, here’s how to write a short story step-by-step:

Step by step, we’ll show you how to take a blank page and spin it into short-form narrative gold.

1. Identify a short story idea

Before you can put your head down and write your story, you first need an idea you can run with. Some writers can seemingly pluck interesting ideas out of thin air but if that’s not you, then fear not. Here are some tips and tricks that will get your creative juices flowing and have you drumming up ideas in no time.

Start with an interesting character or setting

Short stories, by their very nature, tend to be narrower in scope than a novel. There’s less pressure to have a rich narrative mapped out from A to Z before your pen hits the paper. Short story writers often find it fruitful to focus on a single character, setting, or event — an approach that is responsible for some true classics.

John Cheever’s “The Swimmer” is about one character: a suburban American father who decides to swim through all of his neighbor’s pools. While Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery” has a larger cast of characters, the story takes place perhaps over one hour in a town square. By limiting yourself to a few characters and one or two locations, you may find it easier to keep your story from getting out of hand and spiraling off into tangents.

Mine your own anecdotes

When it comes to establishing a story’s premise, real-life experiences can be your first port of call — “write what you know”, as the old adage goes. While you might not have lived through an epic saga akin to Gulliver’s Travels, you probably have an anecdote or two that would easily form the basis of a short story. If there’s a funny story you always reach for at a party or a family dinner, you could repurpose for a piece of writing or let it serve as a launchpad for your imagination.

Eavesdrop and steal

There is beauty in the mundane. Writers these days often have a document open in their phone’s notes app to remember things that might spark their imagination at a later date. After all, something you overhear in a conversation between your aunties could be perfect short story fodder — as could a colorful character who turns up at your workplace. Whether these experiences are the basis for a story or function as a small piece of embellishment, they can save your imagination from having to do all the heavy lifting.

It’s not just your own life you can take inspiration from either. Pay extra attention to the news, the stories your friends tell you, and all the things that go on around — it will surely serve you well when it comes to brainstorming a story.

Try a writing prompt on for size

If you’re still stumped, looking through some short story ideas or writing prompts for inspiration. Any stories that are written with these resources are still your intellectual property, so you can freely share or publish them if they turn out well!

Once you have your idea (which could be a setting, character, or event), try to associate it with a strong emotion. Think of short stories as a study of feeling — rather than a full-blown plot, you can home in on an emotion and let that dictate the tone and narrative arc. Without this emotion core, you may find that your story lacks drive and will struggle to engage the reader.

With your emotionally charged idea ready to go, let’s look at structure.

2. Define the character’s main conflict and goal

You might be tempted to apply standard novel-writing strategies to your story: intricately plotting each event, creating detailed character profiles, and of course, painstakingly mapping it onto a popular story framework with a beginning, middle, and end. But all you really need is a well-developed main character and one or two big events at most.

Short stories should have an inciting incident and a climax

A short story, though more concise, can still have all of the narrative components we’d expect from a novel — though the set up, inciting incident, and climax might just be a sentence or two. As Kurt Vonnegut would say, writers should aim to start their stories “as close to the end as possible”. Taking this advice to the extreme, you could begin your story in medias res, skipping all exposition and starting in the middle of the action, and sustaining tension from there on in.

What’s most important to remember is that short stories don’t have the same privilege of time when it comes to exposition. To save time and make for a snappier piece of writing, it’s usually better to fold backstory into the rising action.

Each scene should escalate the tension

Another effective short story structure is the Fichtean Curve, which also skips over exposition and the inciting incident and starts with rising action. Typically, this part of the story will see the main character meet and overcome several smaller obstacles (with exposition snuck in), crescendoing with the climax. This approach encourages writers to craft tension-packed narratives that get straight to the point. Rarely do you want to resolve the main conflict in the middle of the story — if there’s an opportunity for tension, leave it open to keep the momentum going until the very end.

Don’t be afraid to experiment with structure and form

Short stories by design don’t really have the time to settle into the familiar shape of a classic narrative. However, this restriction gives you free rein to play around with chronology and point of view — to take risks, and be experimental. After all, if you’re only asking for 20 minutes of your readers’ time, they’re more likely to go along with an unusual storytelling style. Classic short stories like Flannery O’Connor’s “A Good Man Is Hard to Find” did so well precisely because O’Connor redrew the parameters of the South Gothic genre as it was known — with its cast of characters, artfully sustained suspense and its shocking, gruesome ending.

3. Hook readers with a strong beginning

A lot rides on the opening lines of a short story. You’ll want to strike the right tone, introduce the characters, and capture the reader’s attention all at once — and you need to do it quickly because you don’t have many words to work with! There are a few ways to do this, so let’s take a look at the options.

Start with an action

Starting with a bang — literally and figuratively — is a surefire way to grab your reader’s attention. Action is a great way to immediately establish tension that you can sustain throughout the story. This doesn’t have to be something hugely dramatic like a car crash (though it can be) — it can be as small and simple as missing a bus by a matter of seconds. So long as the reader understands that this action is in some way unusual, it can set the scene for the emotional turmoil that is to unfold.

Start with an insight

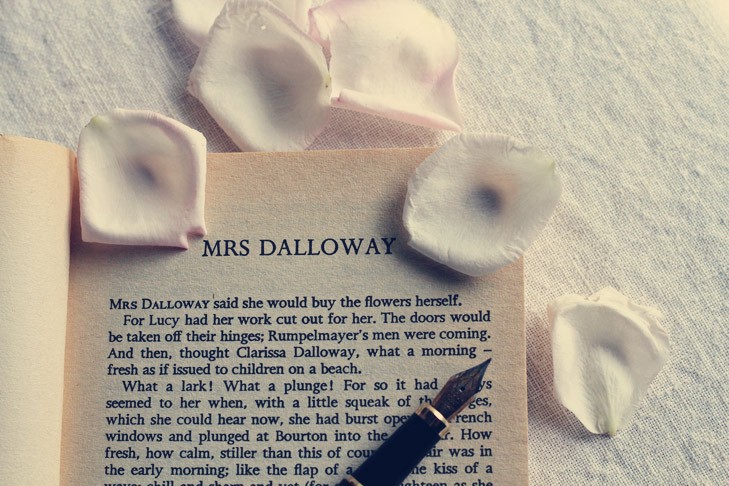

One highly effective method for starting a short story is to write an opening hook. A ‘hook’ can seem an obtuse word, but what it really means is a sentence that immediately garners intrigue and encourages your reader to read on. For example, in “Mrs Dalloway” (originally a short story), Virginia Woolf opens with the line, “Mrs. Dalloway said she would buy the flowers herself.” The reader then wonders: who is Mrs. Dalloway, why is she buying flowers, and is it unusual that she would do so herself? Such questions prompt the reader to continue with interest, looking for answers.

Start with an image

Another popular way of opening a story by presenting your reader with a strong image. It could be a description of an object, a person, or even a location. It’s not to everyone’s taste (especially if you love plot driven stories), but when done well, a well-drawn image has the ability to linger on the reader’s mind. Let’s go back to our example of Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery”. This story starts opens with a vivid and detailed description of a village:

The morning of June 27th was clear and sunny, with the fresh warmth of a full-summer day; the flowers were blossoming profusely and the grass was richly green.

Though this description seems to be setting the stage for a pleasant, lighthearted tale, “The Lottery” actually takes a darker turn — making this opening image of an idyllic summer’s day even more eerie. When this story was published in The New Yorker, readers responded by sending in more letters than for any story that had come before — that’s how you know you’ve made an impact, right?

[PRO-TIP: To read some of the best short stories, head here to find 31 must-read short story collections.]

4. Draft a middle focused on the story’s message

The old maxim of “write drunk, edit sober” has long been misattributed to Ernest Hemingway, a notorious drinker. While we do not recommend literally writing under the influence, there is something to be said for writing feely with your first draft.

Tell us about your book, and we’ll give you a writing playlist

It’ll only take a minute!

Don’t edit as you write

Your first draft is not going to be fit for human consumption. That’s not the point of it. Your goal with version 1 of the story is just to get something out on the page. You should have a clear sense of your story’s overall aim, so just sit down and write towards that aim as best you can.

Avoid the temptation to noodle with word choice and syntax while you’re on the first draft: that part will come later. ‘Writing drunk’ means internalizing the confidence of someone on their second bottle of chablis. Behave as though everything you’re writing is amazing. If you make a spelling mistake? Who cares! Does that sentence make sense? You’ll fix that later!

Backstory is rarely needed

Hemingway’s Iceberg Theory — correctly attributed to the man — is well suited to short stories. Like the physical appearance of an Iceberg, most of which is “under the surface”, much can be inferred about your story through a few craftily written sentences. Instead of being spoon-fed every single detail, your reader can ponder the subtext themselves and come to their own conclusions. The most classic example of this is “For sale: baby shoes, never worn” — a six-word story with a whole lot of emotionally charged subtext. (Note: that story is attributed to Hemingway, though that claim is also unsubstantiated!)

In short, don’t second-guess yourself and if your story truly needs more context, it can always be added in the next revision.

5. Write a memorable ending

Nothing is more disappointing to a reader than a beautifully written narrative with a weak ending. When you get to the end of your story, it may be tempting to dash off a quick one and be done with it— but don’t give in to temptation! There are countless ways to finish a story — and there’s no requirement to provide a tidy resolution — but we find that the most compelling endings will center on its characters.

What has changed about the character?

It’s typical for a story to put a protagonist through their paces as a means to tease out some kind of character development. Many stories will feature a classic redemption arc, but it’s not the only option. The ending might see the main character making a choice based on having some kind of profound revelation. Characters might change in subtler ways, though, arriving at a specific realization or becoming more cynical or hopeful. Or, they might learn absolutely nothing from the trials and tribulations they’ve faced.

In O. Henry’s Christmas-set “The Gift of the Magi,” a young woman sells her hair to buy her husband a chain for his pocket watch. When the husband returns home that night, he reveals that he sold his watch to buy his wife a set of hair ornaments that she can now no longer use. The couple has spent the story worrying about material gifts but in the end, they have learned that real gift… is their love for one another.

Has our understanding of them changed?

Human beings are innately resistant to change. Instead of putting your characters through a great epiphany or moment of transformation, your ending could reveal an existing truth about them. For example, the ending might reveal that your seemingly likable character is actually a villain — or there may be a revelation that renders their morally dubious action in a kinder light.

This revelation can also manifest itself as a twist. In Ambrose Bierce’s “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge,” a plantation owner in the Civil War escapes the gallows and embarks on a treacherous journey home. But just before he reaches his wife’s waiting arms, he feels a sharp blow on the back of his neck. It is revealed that he never actually left the gallows — his escape was merely a final fantasy.

For these character-driven endings to work, the readers need to be invested in your characters. With the precious few words that you have to tell your story, you need to paint enough of a picture to make readers care what actually happens to them at the end.

More often than not, if your ending falls flat, the problem usually lies in the preceding scenes and not the ending. Have you adequately set up the stakes of the story? Have you given readers enough of a clue about your twist ending? Does the reader care enough about the character for the ending to have a strong emotional impact? Once you can answer yes to all these questions, you’re ready to start editing.

6. Refine the plot and structure of your short story

If you’re wondering how to make your story go from good to great, the secret’s in the editing process. And the first stage of editing a short story involves whittling it down until it’s fighting fit. As Edgar Allan Poe once said, “a short story must have a single mood and every sentence must build toward it,”. With this in mind, ensure that each line and paragraph not only progress the story, but also contributes to the mood, key emotion or viewpoint you are trying to express. Poe himself does this to marvelous effect in “The Tell-Tale Heart”:

Slowly, little by little, I lifted the cloth, until a small, small light escaped from under it to fall upon — to fall upon that vulture eye! It was open — wide, wide open, and my anger increased as it looked straight at me. I could not see the old man’s face. Only that eye, that hard blue eye, and the blood in my body became like ice.

Edit ruthlessly

The rewrites will often take longer than the original draft because now you are trying to perfect and refine the central idea of your story. If you have a panic-stricken look across your face reading this, don’t worry, you will probably be more aware of the shape you want your story to take once you’ve written it, which will make the refining process a little easier.

A well-executed edit starts with a diligent re-read — something you’ll want to do multiple times to ensure no errors slip through the net. Pay attention to word flow, the intensity of your key emotion, and the pacing of your plot, and what the readers are gradually learning about your characters. Make a note of any inconsistencies you find, even if you don’t think they matter — something extremely minor can throw the whole narrative out of whack. The problem-solving skills required to identify and fix plot holes will also help you eventually skim the fat off your short story.

What to do if it’s too long

Maybe you’re entering a writing contest with a strict word limit, or perhaps you realize your story is dragging. A simple way to trim your story is to see if each sentence passes the ‘so what?’ test — i.e., would your reader miss it if it was deleted?

See also if there are any convoluted phrases that can be swapped out for snappier words. Do you need to describe a ‘400ft canvas-covered, steel-skeleton hydrogen dirigible’ when ‘massive airship’ might suffice?

Get a second opinion

Send your story to another writer. Sure, you may feel self-conscious but all writers have been embarrassed to share their work at some point in their lives— plus, it could save you from making major mistakes. There’s nothing like a fresh pair of eyes to point out something you missed. More than one pair of eyes is even better!

Consider professional editing

Now that you know how to a short story people will want to read, why not get it out into the world? In the next post in this series, discover your best options for getting your short story published.

How to Write a Short Story

This article was co-authored by Stephanie Wong Ken, MFA. Stephanie Wong Ken is a writer based in Canada. Stephanie’s writing has appeared in Joyland, Catapult, Pithead Chapel, Cosmonaut’s Avenue, and other publications. She holds an MFA in Fiction and Creative Writing from Portland State University.

There are 7 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page.

This article has been viewed 4,596,839 times.

For many writers, the short story is the perfect medium. It is a refreshing activity. For many, it is as natural as breathing is to lungs. While writing a novel can be a Herculean task, just about anybody can craft—and, most importantly, finish—a short story. Writing a novel can be a tiresome task, but writing a short story, it’s not the same. A short story includes setting, plot, character and message. Like a novel, a good short story will thrill and entertain your reader. With some brainstorming, drafting, and polishing, you can learn how to write a successful short story in no time. And the greatest benefit is that you can edit it frequently until you are satisfied.

Sample Short Stories

Making Characters that Pop:

Finding Inspiration: Characters are all around you. Spend some time people-watching in a public place, like a mall or busy pedestrian street. Make notes about interesting people you see and think about how you could incorporate them into your story. You can also borrow traits from people you know.

Crafting a Backstory: Delve into your main character’s past experiences to figure out what makes them tick. What was the lonely old man like as a child? Where did he get that scar on his hand? Even if you don’t include these details in the story, knowing your character deeply will help them ring true.

Characters Make the Plot: Create a character who makes your plot more interesting and complicated. For example, if your character is a teenage girl who really cares about her family, you might expect her to protect her brother from school bullies. If she hates her brother, though, and is friends with his bullies, she’s conflicted in a way that makes your plot even more interesting.

Cambridge B1 Preliminary (PET): How to write a story in 2021

Cambridge B1 Preliminary (PET): How to write a story in 2021

Summary

As the plane flew lower, Lou saw the golden beaches of the island below. The sun was shining brightly and he said to the woman next to him, “I’m so excited about my holidays!”

As soon as Lou got off the plane he left the airport and took a taxi to the city centre because he really wanted to swim in the clear water and sunbathe on the beautiful beach he had seen earlier.

However, when he arrived at the beach he saw that the weather was changing and five minutes later it was raining heavily. Lou ran into a bar and was surprised because someone shouted, “Hi, it’s you again!”

There was the woman from the plane! They started to talk and became very good friends.

Introduction

Part 1 of the the Writing exam in B1 Preliminary is always an email. You can’t choose this task, but in the second part of the test you can decide if you want to write an article or a story.

In every story task you get one sentence which has to be the first sentence of your story and the text has to be related to this. Your language should be neutral to informal.

What does a typical story task look like?

Whenever you get ready for a writing task in the PET exam, you need to think about a few questions. These questions help you understand the task better and make a plan for your story.

Let’s have a look at a typical example task and see how we can answer the questions above.

You can see that there isn’t a lot of information, but we still have to check the task very carefully so we know exactly what to do.

In the given sentence a person called Lou is on a plane flying over an island and he’s looking at the beaches. The plane is going lower so it might be getting ready to land. This is the situation you have to start your story from and everything you write has to be related to this beginning.

The second question is a little bit more open than the first one because you can pretty much write about anything you like. The only restriction, again, is the first sentence and the situation that comes with it. You can make your story funny, sad, full of action or fantasy and include whatever you can imagine, but connect it to the first sentence.

Last but not least, your English teacher is going to read your story. In other writing tasks you need to be very careful with your language, but in a story you are freer. You decide if your characters use very formal English or if they are informal. Just remember, don’t use rude language or words that are not in the dictionary.

You see, there is a lot of freedom that you have when you write a story, but, at the same time, you have to make sure that you focus on the topic in the first sentence and that you are careful with your language because the rules are not as strict as in an email or article.

How to organise your story

The good thing about B1 Preliminary writing tasks is that you can always organise them in the same way. It is a little bit like a good cooking recipe because it works every time.

A good story usually has a beginning, a main part and an ending. The main part is the most important one so you want make it longer than the other parts. Most of the time, we get to a structure that looks like this:

Of course, you might have three main part paragraphs, but in most tasks the structure with only two works very well.

Always plan your story

If you start to write your story without thinking about it first, you might run into some big problems. You can’t really change everything once you’ve started because you only have 45 minutes to write your story AND an email.

That’s why you should always make a plan. Use the structure above and just add a few ideas so it works like a map. You will know exactly where your story is going and you only have to worry about using good language.

The different parts of a story

Now, we are going to find out what the different parts of a story typically look like and I will give you some useful tips about good language that will help you get good marks.

First sentence / Beginning

As I said above, in a PET story you always have to start with a sentence that you get directly from the task. Don’t change this sentence in any way, but simply copy it onto you answer sheet and begin your story from there.

I recommend adding one more sentence to complete the beginning of your story. For our example task this could look like this:

As the plane flew lower, Lou saw the golden beaches of the island below. The sun was shining brightly and he said to the woman next to him, “I’m so excited about my holidays!”

When we look at the first sentence from the task, there are a couple of things that are not 100% clear. For example, why was Lou on the plane? What island did he see? Why did the plane fly lower? In my second sentence I tried to make things a little bit clearer. Lou was on his way to spend his holidays on the island and the plane was getting ready for landing.

In terms of good language, I used past continuous (was shining), which we use to say what was happening in the background or at the same time as our main events. I also included an adverb (brightly) and an adjective (golden), which makes an action more interesting, and there is some direct speech (“I’m so excited about my holidays!”). This brings the reader closer to the characters compared to indirect or reported speech.

Always try to make sure to set the scene. Give some background information (past continuous) to introduce the main character(s). Add some adjectives and adverbs as well as direct speech because this makes the reader feel more interested in your story and they want to keep reading.

Main paragraphs

Once we set the scene, we can move on to the main part of the story. Here, we try to develop the plot and all the main events happen in these paragraphs. You can decide how many paragraphs you want to make, but in general you should be fine with two or three of them.

For our example task I chose two paragraphs:

As soon as Lou got off the plane he left the airport and took a taxi to the city centre because he really wanted to swim in the clear water and sunbathe on the beautiful beach he had seen earlier.

However, when he arrived at the beach he saw that the weather was changing and five minutes later it was raining heavily. Lou ran into a bar and was surprised because someone shouted, “Hi, it’s you again!”

I tried to let the plot grow a little bit in my first main paragraph and, at the same time, create some excitement for the reader. Lou wants to go to the beach, but when I use the word ‘however’ to start the second paragraph, it is clear that something must be wrong. Finally, I end my main paragraphs with a mysterious voice calling for Lou in the bar. The reader wants to know how the story ends.

For useful language, you can find some time expressions (as soon as, when, five minutes later) as well as past perfect and past continuous (had seen, was changing, was raining). These verb forms help us to give extra information around the main events of the story. In addition, there are interesting adjectives (clear, beautiful, surprised) and adverbs (really, heavily). Once again, these words help us make our story more interesting for the reader.

It is also a good idea to use some contrast (however) and surprising elements (someone shouted) in your story because, again, you want to make the story as interesting as possible.

Ending

Every good story has an ending. In PET, you want to finish your story in a surprising and/or funny way so the reader is happy.

Make sure that the ending is connected to the topic. Don’t introduce new characters or let the story move in a completely different direction. Just write one or two last sentences and that’s it.

In my example story I wrote this:

There was the woman from the plane! They started to talk and became very good friends.

It’s a short ending with a little surprising element (the woman from the plane). It is nothing special or crazy, but it brings the whole story together in a nice way. That’s all you have to do to make the examiner happy and get great marks.

Useful language for PET story writing

In this part I’m going to give you a summary of the different types of useful language for your Cambridge B1 story.

Past verb forms

Past simple, past continuous and past perfect are the three most important verb forms when you write a story.

Study these verb tenses and practise as much as you can.

Time expressions

Time expressions put the events of your story in a sequence. When you use them in the right way, the reader understands what happened first and the sequence of events.

Some examples of time expressions that you can use in almost every story are:

Use one or two of these in every paragraph so the examiner is happy and gives you high marks. 🙂

Adjectives and adverbs

Adjectives and adverbs are like different spices in your food. Without them everything tastes a little bit boring so we want to make it as flavourful as possible. Just as with time expressions, always think about where you can use adjectives and adverbs to describe a person, an object, a place or an action in more detail.

Look again at my story with all the adjectives and adverbs highlighted:

As the plane flew lower, Lou saw the golden beaches of the island below. The sun was shining brightly and he said to the woman next to him, “I’m so excited about my holidays!”

As soon as Lou got off the plane he left the airport and took a taxi to the city centre because he really wanted to swim in the clear water and sunbathe on the beautiful beach he had seen earlier.

However, when he arrived at the beach he saw that the weather was changing and five minutes later it was raining heavily. Lou ran into a bar and was surprised because someone shouted, “Hi, it’s you again!”

There was the woman from the plane! They started to talk and became very good friends.

You see that I didn’t overuse adjective and adverbs, but two or three in every paragraph are already going to improve your story a lot.

Direct speech

Direct speech describes the things that somebody actually says in that moment. We always use quotation marks (“) to show that we are using direct speech.

Used in a story it gives the reader the feeling of being closer to the action and the characters feel more alive. Always try to have a couple of sentences in direct speech in your stories.

My examples are:

Practise makes perfect

It is now your turn to practise story writing. Don’t wait until it is too late. With every story you write you will feel more confident and ready for the exam. Practise the different kinds of useful language and step by step you will improve.

I hope my article will help you and if you enjoy my content, leave a comment and let me know what you think.

Ten Secrets to Write Better Stories

Writing isn’t easy, and writing a good story is even harder.

I used to wonder how Pixar came out with such great movies year after year. Then, I found out a normal Pixar film takes six years to develop, and most of that time is spent on the story.

In this article, you’ll learn ten secrets about how to write a story, and more importantly, how to write a story that’s good.

Everything I Know About How to Write a Story

Since I started The Write Practice over a decade ago, I’ve been trying to wrap my head around how to write a good story. I’ve read books and blog posts on writing, taken creative writing courses, asked dozens of other story writers, and, of course, written stories myself.

The following ten steps are a distillation of everything I’ve learned about writing a good story. I hope it makes writing your story a little easier, but more than that, I hope it challenges you to step deeper into your own exploration of how to write a story.

Wait! Need a story idea? We’ve got you covered. Get our top 100 short story ideas here.

1. Write In One Sitting

Write the first draft of your story in as short a time as possible. If you’re writing a short story, try to write it in one sitting. If you’re writing a novel, try to write it in one season (three months).

Don’t worry too much about detailed plotting or outlining beforehand. You can do that once you know you have a story to tell in the first place.

Also, don’t worry about plot holes or getting some details wrong as you write. At this point, you don’t even have to have finalized character names.

Your first draft is a discovery process. You are like an archeologist digging an ancient city out of the clay. You might have a few clues about where your city is buried beforehand, but you don’t know what it will look like until it’s unearthed.

All that’s to say, get digging!

2. Develop Your Protagonist

Stories are about protagonists, and if you don’t have a good protagonist, you won’t have a good story.

The essential ingredient for every protagonist is that they must make decisions. As Victor Frankl said, “A human being is a deciding being.” Your protagonist must make a decision to get themselves into whatever mess they get into in your story, and likewise, their character arc must come to a crisis point and they must decide to get themselves out of the mess.

To further develop your protagonist, use other character archetypes like the villain, the protagonist’s opposite, or the fool, a sidekick character that reveals the protagonist’s softer side.

It’s a good idea to develop a character profile for every single character. This will help you make more believable characters and keep you from getting character details wrong. Some kind of character sheet is essential for your POV character at the very least.

Note: Character development isn’t just for fictional characters! You need to have a well-rounded character if you’re writing memoir/personal narratives (you’re the perspective character) or certain types of nonfiction as well. Readers fall in love with characters.

3. Create Suspense and Conflict

Conflict is essential to every type of story. Conflict is what drives your characters and what keeps your readers reading. If there is no conflict, your reader will be bored, and there is no story.

There are two basic types of conflict. External conflict is the action of your story, the thing everyone sees on the surface. But don’t forget about internal conflict! This is the process of your POV character warring with themselves and is what sets up the crisis point of the story and the character arc.

You also need suspense for a compelling story. Suspense isn’t just for thrillers; it’s a plus for any type of story.

To create suspense, set up a dramatic question. A dramatic question is something like, “Is he going to make it?” or, “Is she going to get the man of her dreams?” By putting your protagonist’s fate in doubt, you make the reader ask, what happens next?

To do this well, you need to carefully restrict the flow of information to the reader. Nothing destroys drama like over-sharing.

4. Show, Don’t Tell

Honestly, the saying “show, don’t tell” is overused. However, when placed next to the step above, it becomes very effective.

When something interesting happens in your story that changes the fate of your character, don’t tell us about it. Show the scene! Your readers have a right to see the best parts of the story play out in front of them. Show the interesting parts of your story and tell the rest.

5. Write Good Dialogue

Good dialogue comes from two things: intimate knowledge of your characters and lots of rewriting.

Each character must have a unique voice, and to make sure your characters all sound different, read each character’s dialogue and ask yourself, “Does this sound like my character?” If your answer is no, then you have some rewriting to do. (Want more character development tips? Click here.)

Also, with your speaker tags, try not to use anything but “he said” and “she said.” Speaker tags like “he exclaimed,” “she announced,” and “he spoke vehemently” are distracting and unnecessary. The occasional “he asked” is fine, though.

6. Write About Death

Think about the last five novels you read. In how many of them did a character die?

Best-selling fiction often involves death. Harry Potter, The Hunger Games, Charlotte’s Web, The Lord of the Rings, and more all had main characters who died.

Death is the universal theme because every person who lives will one day die. You could say humans versus death is the central conflict of our lives. Tap the power of death in your storytelling.

7. Edit Like a Pro

Most professional writers have an established writing process that often involves writing three drafts or more. The first draft is often called the “vomit draft” or the “shitty first draft.” Don’t share it with anyone! Your first draft is your chance to explore your story and figure out what it’s about.

Editing is often the part of the writing process that causes the most anxiety, but it’s necessary. Your second draft isn’t for polishing, although many new writers will try to polish as soon as they can to clean up their embarrassing first draft.

Instead, the second draft is meant for major structural changes (make sure it’s a complete story!), for cleaning up any plot holes, or for clarifying the key ideas if you’re writing a non-fiction book. This is where you make sure your story is complete, has believable characters (they should have character names now!), and that everything makes sense.

(Need a refresher on the basics of story structure? Click here.)

The third draft is for deep polishing. Now is when everything starts to gel. This is the fun part! But until you write the first two drafts, polishing is probably a waste of your time.

8. Know the Rules, Then Break Them

Good writers know all the rules for the type of story they’re writing and follow them. Great writers know all the rules and break them.

However, the best writers don’t break the rules arbitrarily. They break them because their stories require a whole new set of rules.

Respect the rules, but remember that you don’t serve the rules. You serve your stories.

9. Defeat Writer’s Block

The best way to defeat writer’s block is to write. If you’re stuck, don’t try to write well. Don’t try to be perfect. Just write.

Sometimes, to write better stories, you have to start by taking the pressure off and just writing.

10. Share Your Work

You write better when you know someone will soon be reading what you’ve written. If you write in the dark, no one will know if you aren’t giving your writing everything you have. But when you share your writing, you face the possibility of failure. This will force you to write the best story you possibly can and to amp up your creative writing skills with each story you write.

(Not quite ready to publish, but are interested in beta readers? Read our definitive guide on beta readers here.)

One of the best ways to write a story and share your writing is to enter a writing contest. The theme will inspire a new creation, the deadlines will keep you accountable, and the prizes will encourage you to submit—and maybe win! We love writing contests here at The Write Practice. Why not enter our next one?

How to Write a GOOD Story

All these tips will help you write a story. The trick to writing a good story? Practice. Practice on a daily basis if you can with a regular writing schedule.

When you finish the story you’re writing, celebrate! Then, start your next one. There’s no shortcut besides this: keep writing. Even using the best book writing software or tools like ProWriting Aid (check out our ProWritingAid Review) won’t help compared to continuing to write.

PRACTICE

Do you have a story to tell?

Take fifteen minutes to start. Write the first draft of a short story in one sitting using the tips above.

Need a prompt to get started? Try this one: She was pretty sure that tree hadn’t been there yesterday.

Then, share your story in the practice box below. (Now you’re practicing tip #10!) And if you share your practice, be sure to leave feedback on a few practices by other writers, too. Excited to see your story take shape!

How to write a short story: 10 steps to a great read

Writing a short story differs from writing a novel in several key ways: There is less space to develop characters, less room for lengthy dialogue, and often a greater emphasis on a twist or an ‘a-ha’ moment. How to write a short story in ten steps:

Writing a short story differs from writing a novel in several key ways: There is less space to develop characters, less room for lengthy dialogue, and often a greater emphasis on a twist or an ‘a-ha’ moment. How to write a short story in ten steps:

How to plan a short story, write and publish

1: Find the scenario for your story

Writing a novel gives you time to develop characters and story arcs and symbols.

Writing a short story differs. There is often a single image, symbol, idea or concept underlying the story. Some examples of original story scenarios:

Find a scenario you can write down in a sentence or two. An interesting scenario that sets the story in motion has multiple benefits:

On the topic of publishers:

2: Plan what publications you’ll submit your final story to

One of the benefits of writing short stories is that there are many publishing opportunities for short fiction.

You can publish short fiction in:

Make a list of possible publications, once you have decided on your core story scenario.

When you research publications that accept short fiction, note:

It’s wise to have these guidelines for formatting, word count and areas of interest worked out before you start. This will enable you to make your story meet requirements for acceptance. This will save time later when it comes to revising.

So you have the story idea worked out and a list of publications and their requirements? Now it’s time to find your short story’s focus:

3: Find the focus of your story

The scenario of your short story is the idea or image that sets the story in motion.

The focus of your story matters. What do you want to say? Why write a short story on this subject in particular?

The first step of Now Novel’s step-by-step story building process, ‘Central Idea’, will help you find your idea and express it as a single paragraph you can grow. Try it now.

Finding the focus of your short story before you start is explained by Writer’s Relief via the Huffington Post thus:

Explore your motivations, determine what you want your story to do, then stick to your core message. Considering that the most marketable short stories tend to be 3,500 words or less, you’ll need to make every sentence count.

If you were Gabriel Garcia Marquez, for example, you might describe the scenario for your short story ‘The Handsomest Drowned Man in the World’ (a dead man washing up on a beach) thus:

‘Focus: Rural life and the way the introduction of new, unfamiliar things changes it. Also: Death and how people respond to and make sense of it.’

Once you have an idea of the topic, themes and focus of your short story, it’s easier to outline characters who fit these elements:

4: Outline your characters and setting(s)

Writing a book makes outlining essential, given the complexity of long-form fiction.

You might think ‘Why should I bother with outlining a short story?’ The truth is that it is useful for similar reasons: Outlining gives you creative direction and helps to make your writing structured and internally consistent.

Once you have the scenario, topics and themes for your story, make a list for each character idea you have. Make notes on character elements such as:

[Get our guide ‘How to Write Real Characters’ for extra help crafting unique, believable characters.]

Similarly, for setting, write down:

Start gathering ideas

Brainstorm your best ideas for a short story in easy, helpful steps.

5: Choose a point of view for the story

Point of view (or POV) can have subtle effects.

For example, a character who narrates the story in the first-person may seem strong and self-possessed. You could make the same character seem much less powerful by using the third person limited instead.

An example of this is James Joyce’s use of the second person in his story ‘Clay’ from the collection Dubliners.

The focal character in Joyce’s short story is a cook named Maria. Joyce uses third person limited throughout to describe Maria and her daily life.

Maria’s own story not being told through the first person conveys a sense of her social position – she is a ‘she’ who is likely marshalled around by wealthy employers. The story simply wouldn’t achieve the same sense of Maria’s marginal status were it written in first person.

Dennis Jerz and Kathy Kennedy share useful tips on choosing point of view:

Point of view is the narration of the story from the perspective of first, second, or third person. As a writer, you need to determine who is going to tell the story and how much information is available for the narrator to reveal.

They describe the pros and cons of each point of view:

First person POV:

A character narrates the story using the pronoun ‘I’.

Pros: One of the easiest POVs for beginners; it allows readers to enter a single character’s mind and experience their perceptions.

Cons: The reader doesn’t connect as strongly to other characters in the story.

Second person POV:

Much less common, this addresses the reader as a character in the story, using the pronoun ‘You’.

Pros: Novel and uncommon; the reader becomes an active story participant.

Cons: The environment of the story can feel intangible as the reader has to imagine the story setting as her immediate surroundings.

Third person POV:

The story is told using he/she/it. In omniscient POV, the narrative is told from multiple characters’ perspectives, though indirectly.

Pros: This POV allows you to explore multiple characters’ thoughts and motivations.

Cons: Switching between different characters’ perspectives must be handled with care or the reader could lose track of who is the viewpoint character.

Third person limited POV:

The story uses he/she but from one character’s perspective – only their individual experience supplies what the narrator knows.

Pros: The reader enjoys the intimacy of a single character’s perspective.

Cons: We only understand other characters’ views and actions through the perceptions of the viewpoint character.

As you can see, choosing POV requires thinking about both who you want to tell your story and what this decision will mean.

6: Write your story as a one page synopsis

This might seem like a dubious idea. After all, how will you know where the story will take you once you start writing?

The truth is that even just attempting this as an exercise will give you an idea of the strong and weak points of your story idea: Is there potential for an intriguing climax? Will the initial premise hook your reader?

You should at least try to write your short story in condensed form first for other reasons, too:

Joe Bunting advocates breaking your story into a scene list so that you have a clear overview of the structure of your story and the parts that require additional work.

7: Write a strong first paragraph

You don’t necessarily need to begin writing your story from the first paragraph. The chances are that you will need to go back and revise it substantially anyway. Bunting actually advises against starting a short story with the first paragraph because the pressure to create a great hook can inhibit you from making headway. Says Bunting:

‘Instead, just write. Just put pen to paper. Don’t worry about what comes out. It’s not important. You just need to get your short story started.’

Whether you are intent on starting with the beginning or prefer to follow Bunting’s advice, here are important things to remember about your opening paragraph. It should:

Discussing writing catchy first paragraphs, Jerz and Kennedy suggest:

‘The first sentence of your narrative should catch your reader’s attention with the unusual, the unexpected, an action, or a conflict. Begin with tension and immediacy.’

8: Create a strong climax and resolution for a satisfying story arc

The climax of a story is crucial in long as well as short fiction. In short stories in particular, the climax helps to give the story a purpose and shape – a novel can meander more. Many short story writers have favoured a ‘twist in the tale’ ending (the American short story author O. Henry is famous for these).

The climax could be dramatically compelling. It could be the reader’s sudden realisation that a character was lying, for example, or an explosive conflict that seemed inevitable from the first page.

There are many ways to end a short story well. Besides using an element of surprise you can have an ending that:

These are just three possible types of short story resolution. After the final full stop the crucial revision process begins:

9: How to write a short story that gets published: Rewrite for clarity and structure

Revising is just as important when writing short stories as it is when writing novels. A polished story greatly increases your chance of publication. While revising your short story, see to it that:

10: Pick a great story title and submit your revised story to contests and publishers

Choosing a title for your short story should come last because you will have the entire narrative to draw on. A great title achieves at least two things:

Once you have created an alluring title, you can set about submitting your story to publications. If you are not yet an established author, it may be easier to get published on a digital platform such as an online creative writing journal. Spread the net wide, however, and submit wherever your short story meets guidelines and topical preferences. This will maximize the chance your short story will be published.

Ready to write a winning short story? The short story writers’ group on Now Novel is the place to get helpful feedback on story ideas and drafts.