How to write chinese characters

How to write chinese characters

How to Write Chinese Characters (Quick Start Guide)

I`ve been a Chinese teacher for a long time and I’m frequently asked about writing Chinese characters. This article will summarize my thoughts on this issue which I hope will help all Chinese character learners. Here are the top two questions I get about how to write Chinese characters:

Q1: “Jing, do I really need to learn how to write in Chinese?”

Because of technology, nowadays more and more people tend to just learn Pinyin and then type Chinese characters instead of writing them down. It indeed seems more convenient and easier. However, for a Chinese learner, writing can help you remember the characters more accurately and systematically. If you just type on a computer of a cellphone, you might go through a period when you will suddenly stop using Chinese, then it becomes so easy to forget the words because many characters are just too similar. With actual writing, your muscle memory will help you remember and master these characters much longer because they become a part of your brain. Besides, writing is also a part of understanding Chinese culture. So, my answer is YES, I recommend that you learn how to write in Chinese.

Q2: “Do you have any suggestions on how to write Chinese characters?”

Answering this question is not that simple, so I`ll use the rest of this article to give my best thoughts about this.

1. A basic introduction of Chinese characters

Chinese characters are relatively independent from the phonetic system. There are about 80,000 characters in total and about 6,500 which are used daily. Each character has its own pronunciation, though many of them share the same pinyin syllables. The large number may make many beginners feel scared and overwhelmed. Actually, after knowing the principle of making characters and the rules behind it, mastering the writing of characters should be quite easy. It`s like a “one formula fits all” method.

Traditional or Simplified characters?

We all know that there are two versions of Chinese characters in us nowadays: traditional Chinese characters (繁体字)and simplified Chinese characters (简体字). The traditional version is mainly used in Hongkong, Taiwan, Singapore, and a several other places. The simplified version is mainly used in mainland China. No matter which version you choose to learn, the rules of writing are the same. So, in learning how to write, the version you wish to learn doesn’t really matter.

2. Character formation

Obviously, such a large number of characters cannot be made randomly. Following certain rules, these characters which have grown over thousands of years are still very dynamic.

The formation of characters seems just like a “LEGO” game! There are many small components, and you just need to put the small components together and give them order. Each of the components are made of smaller strokes.

Strokes

The strokes of Chinese characters refer to one uninterrupted dot or line, such as “一”(横)、“丨”(竖)、 “丿”(撇)、“丶”(点)、“乛”(折), etc. A stroke is the smallest component of a character. There are 8 traditional fundamental strokes, which are “丶”(点)、“一”(横)、“丨”(竖)、 “丿”(撇)、 “乀” (捺)、 “㇀”(提)、 “乛” (折) and “亅” (钩).It`s also called “’永’字八法” (yǒngzìbāfǎ). The character “永” basically represents the common stroke types of the Chinese character system.

The modern modular strokes are regulated as the 5 one’s, “一”(横)、“丨”(竖)、 “丿”(撇)、“丶”(点)and“乛” (折), and they are called “’札’字法” (zházìfǎ). It`s a simpler version of “’永’字八法”.

Radicals

Radicals in Chinese characters are called 部首[bùshǒu]. They are used to classify the character patterns which are commonly used in Chinese dictionaries. There are mainly two types of radicals depending on their different functions and properties. One is based on the principles of the six categories of Chinese characters (which we will illustrate more in the content that follows), and the other is based on the shapes of the structures.

Once you understand the relations among strokes, radicals, and characters, writing characters becomes a piece of cake. Moreover, you can not only imitate drawing the shapes, but also understand the underlying rules and reasons behind the characters. Of course, practicing with understanding would be a much better way than mechanical imitation.

Let`s take “女” as an example. “女” is not only a independent character which means female, but it is also a radical which can be combined with other Chinese components and indicates some certain meanings. As the following picture shows, “妈”“姐”“妹” are all females, thus they share the same radical while the right sides are diversified because of the phonetics.

The categories of Chinese characters

There are six main categories of Chinese characters: Pictographs (象形字), Pictophonetic characters (形声字), Simple ideograms(指示字), Compound ideographs (会意字), Phonetic loan characters (假借字), and Derivative cognates (转注字). Here, I will introduce the four commonly used categories:

1). Pictographs (象形字)

These are stylised drawings of the objects they represent. Many Chinese learners feel that they are “drawing” Chinese characters, and in this case, they are! Most of the single characters and radicals are from this category.

2) Pictophonetic characters (形声字)

They are also called radical-phonetic characters. Over 70% of Chinese characters were created by this method. There are mainly two components: the phonetic component and the semantic component. The “女” radical we mentioned before is a typical example of this category.

女 à the meaning part (also the radical), “female”

“妈”“姐”“妹” à“马” “且” “未” indicate the phonetic part.

3) Simple ideograms(指示字)

These express an abstract idea through an iconic form. For example, the numbers in Chinese, “一” “二” “三”, are represented by the appropriate number of strokes which means “one” “two” “three”.

4) Compound ideographs (会意字)

These are the combination of two or more pictographic characters to suggest the meaning of the character to be represented.

林(lín) à woods (two 木)

森(sēn) à forest (three 木)

3. The Basic Writing Order

Stroke order really matters if you want to learn writing characters. Using the wrong stroke order or direction would cause the ink to fall differently on the page. The Chinese stroke order system was designed to produce the most aesthetical, symmetrical, and balanced characters on a piece of paper. Furthermore, it was also designed to be efficient – creating the most strokes with the least amount of hand movement across the page. Here, I`ll quote the rules that Sara once wrote in the article Why Chinese Stroke Order is Important and How to Master it at DigMandarin to show you the proper stroke orders.

Here are some tips on mastering stroke order.

1). 从上到下Top to bottom

When a Chinese character is “stacked” vertically, like the character 立 (lì) which means to stand, the rule is to write from top to bottom.

2). 从左到右Left to right

When a Chinese character has a radical, the character is written left to right. The same rule applies to characters that are stacked horizontally.

3). 先中间后两边Symmetry counts

When you are writing a character that is centered and more or less symmetrical (but not stacked from top to bottom) the general rule is to write the center stroke first.

4). 先横后竖Horizontal first, vertical second

Horizontal strokes are always written before vertical strokes. Here is how to write the character “十(shí)” or “ten.”

5). Enclosures before content

You want to create the frame of the character before you fill it in. Check out how to write the character 日(rì) or “sun.”

6). Close frames last

Make a frame then fill in some of the components inside. After you write the middle strokes, close the frame, such as in the character “回(huí)” or “to return.”

7). Character spanning strokes are last

For strokes that cut across many other strokes, they are often written last. For example, the character 半 (bàn), which means “half.” The vertical line is written last.

There are always small exceptions to the rule, and Chinese stroke order can vary slightly from region to region. However, these variations are very miniscule; so by following these general tips, you’ll have an astute grasp on Chinese character`s writing order.

From strokes to characters, this is the way Chinese characters are formed. And it should also be the way you learn to write them. Writing is not the final goal, but understanding and using them correctly. Following the order of the writing will help you remember the characters better.

So, I hope you like this guide to learning how to write Chinese characters! get your pen and let`s start writing!

JING CAO

Jing Cao is the chief-editor and co-founder of DigMandarin. She has a master’s degree in Chinese Linguistics and Language Aquisition and has taught thousands of students for the past years. She devotes herself to the education career of making Chinese learning easier throughout the world.

How to write chinese characters

Many people think that they have “bad memories”, but did you know that most people have strikingly similar memory capacities? 1 The way that we use our memories is far more important than our brain’s genetic makeup.

Forgetting how to write a Chinese character that you’ve studied before happens so often for Chinese learners. Even native speakers get frustrated with forgetting how to write characters. Let’s pause for a moment and consider a new strategy for learning Chinese characters.

Our brains our wired to be associative, meaning that we remember best when we can connect a memory to something that affected us emotionally. Unfortunately, written Chinese is taught for the most part through rote learning which is basically just repeating something over and over again. This type of learning is hard and unnatural. It does not work well for non-native speakers, especially for those who are learning Chinese as adults.

Remember that you need to not only learn but also be able to recall at least 4000 Chinese characters to read at even the most basic level. If you aren’t getting where you want to be in your studies, stop beating yourself up about how you need to simply study more. What you need isn’t more study time, it is a change of technique.

Confucius said it best…

“ 射有似乎君子, 失诸正鸪, 而反求诸身 ” (shè yǒu sìhū jūnzi shī zhū zhèng gū, ér fǎn qiú zhū shēn)

“When it is obvious that the goals cannot be reached, don’t adjust the goals, adjust the action steps.”

To recall characters with ease, you must learn to use your brain as it was intended to be used. You must make your Chinese learning associative. For each character, you must create a story that depicts its meaning. If the story is funny or interesting to you, then it will not be burden to remember it.

Just like with any new memory technique, it takes a bit of practice. After you have done this for 20-30 characters, it gets much easier and you’ll be able rapidly increase the amount of characters you can learn and retain for the long term.

Here’s how to create associative memories with Chinese characters:

First you need to realize that you will have to memorize some odd shapes. There are some Chinese learning programs out there preaching that all Chinese characters look like what they mean. Sadly, this is true for only a small handful of characters, most of which aren’t even used with regularity in modern Chinese. You need to come to terms with the fact that you’ll have to learn radicals as you learned the English alphabet; A is for “apple” just as 艮 is for “hill”.

You can also tap the LEARN MORE button in the online dictionary to get a breakdown of the radicals included in any Chinese character.

Once you know the radicals used in a character, use their meanings to construct sentences or stories that help you associate the character with its definition. You can even add a hint to the pronunciation of the character in the story, or even multiple meanings for characters that have a broader meaning. The point is, the sentence or story must be meaningful to you. In this way, it becomes hard to forget.

This is an example where the radicals neatly fit into a silly story. You can see from the image that the character 糕 (gāo) has 3 radicals: 米, 羊, and 灬. We can see the meaning of each radical incorporated into the sentence in orange. The definition of 糕 (gāo) is “cake”, and we can see that in the sentence in purple.

Here are some more examples where the radicals can relatively easily fit into a simple story:

Here are a few examples which include the pronunciation of the character as well. Often the pronunciation hints are a bit of a stretch, but they can still remind you of the character’s pronunciation. I personally only try to add the pronunciation to the story when I have a hard time remembering it.

As you build up your stories, it will become simpler to create new ones because you can incorporate the stories that you’ve already created into new ones. For example, if you look at the character, 理, you can see that there are 3 radicals: 王, 田, and 土. You could create a story with these radicals. But if you’ve already seen and learned the character 里, then you can build a story based off of the 王 radical plus 里.

Using the story we’ve already created above for 里, we can create this story for 理:

So far in the examples above, the radicals used can be incorporated into a story without too much effort. Unfortunately, sometimes there will be cases where part of the character is not a radical at all. In this case, you can examine the shape and think of a way to incorporate that shape into the story.

The hook at the top of the right side of the 候 character, reminds me of the number 7 so I have incorporated it into the sentence to remember how to write the character.

In this last example, the 觉 character can be pronounced in two different ways and has two distinct meanings. This is why both definitions are incorporated into the story.

In the beginning, creating stories to help you remember Chinese characters challenging. After you have created a handful of stories, it gets much easier and quickly becomes second nature.

Add your stories in the comments section of the Learn More pages on the Written Chinese online dictionary so that you can refer back to them easily should you need a reminder of your story. You can also look in the comments section of those same Learn More pages to see the stories that other learners have created.

Click the LEARN MORE button next to any dictionary entry and scroll down to find the comments section. We use Disqus for our comments, so you can even follow other learners and get notified when they add something to these pages.

As always, happy studying everyone!

Tips When Creating Character Stories:

– Color code any images you create to correspond to the tone color of the character in order to reinforce the character’s tone.

– When creating your story, do your best to build it in the same order that you will write the character. So for the character 理, the story would be: “King Li manages the village” and not “The village is managed by King Li”, because you will write the king radical “王” first.

– Keep a record of all the stories you’ve created so that you can remind yourself about them from time to time. One way to do this is to put them in the Disqus comments section of the Written Chinese Online Dictionary. This way you can learn from other students, and at the same time use the search function of the dictionary to easily locate the stories you’ve written for characters previously.

– Some radicals can be broken down into further radicals. For example, 青 is made of the 屮 radical and the 月 radical. It doesn’t matter whether you use the meaning of 青 or use meanings of 屮 and 月 in your story. Do whatever works best for you.

– To easily find out which radicals make up a character, you can use the Learn More button from the Written Chinese Online Dictionary or you can tap the Writing tab in the Written Chinese Dictionary app to see all the radicals.

– Don’t be afraid to revisit some of your stories and make changes based on what you’ve learned. You may have previously created a story and then later have come up with a better way to remember a radical or combination of radicals. Go ahead and update your stories if it makes things simpler for you.

Learn How to Read and Write Chinese Characters

Chinese Character Tutorial

If you’re interested in reading and writing Chinese characters, there’s no better place to get started than with the numbers 1-10. They are quite simple to write, useful to know, and are exactly the same in both the traditional and simplified writing systems.

So grab a piece of paper and a pencil, give a click on the links below, and try to write the characters with proper stroke order as demonstrated:

| One | Two | Three | Four | Five | Six | Seven | Eight | Nine | Ten |

| 一 | 二 | 三 | 四 | 五 | 六 | 七 | 八 | 九 | 十 |

|

Now that you know these characters, you actually know how to read and write all the numbers through 100. That’s because Chinese follows a very simple pattern for counting:

|

Ready for a challenge? Let’s try something a little more interesting:

| English: | Love | Beauty | Courage | Dragon | Fire |

| Simplified: | 爱 | 美 | 勇气 | 龙 | 火 |

| Traditional: | 愛 | same | 勇氣 | 龍 | same |

|

Because the Chinese simplified system is based on the traditional one, many characters are exactly the same, as we saw with the the numbers 1-10. Even for characters that aren’t the same, you will often be able to see similarities. For example, have a look at the character for «love» in the simplified and traditional systems. Almost the same, right?

The Fundamentals of Chinese Stroke Order

Many people are often fascinated and attracted by Chinese characters. At first glance, characters may look like bizarre pictograms, randomly drawn at will. But did you know that Chinese characters all consist of fixed stroke orders and follow a specific set of rules?

Table of Contents

What is Chinese stroke order and why is it important?

Chinese character stroke order, called 笔画顺序 (bǐhuà shùnxù) or 笔顺 (bǐshùn), refers to the order in which the separate strokes that make up Chinese characters are written.

First learn stroke order, then learn Chinese characters

The Chinese idiom 磨刀不误砍柴工 (módāo bù wù kǎnchái gōng) provides a dose of age-old wisdom: sharpening the axe does not delay cutting the wood.

What does this have to do with Chinese stroke order and learning Chinese characters, you may ask? Everything.

Knowing stroke order accelerates the memorization of characters and unlocks a deeper understanding of the structure of every Chinese character you encounter. Once you know stroke order, you can memorize Chinese characters more quickly.

First learning Chinese stroke order then moving on to character memorization accelerates the study of Chinese characters. For according to the wonderful Chinese dictionary app Pleco, a beard well lathered is half shaved!

The Chinese character for «I» or «me» is 我 (wǒ). As you can see, 我 has 7 total strokes. They follow an exact and specific order, as shown above. You’ll come to learn that this order is for good reason.

Stroke order in a digital world

Many new learners often wonder whether stroke order is even important. After all, if you can successfully write a legible version of a Chinese character, then surely that’s all that matters, right? Especially today, when Chinese characters are often digitized and most people rarely need to write anything by hand, learning stroke order may seem irrelevant.

Although these points are valid, stroke order is still critically important. Correct stroke order ensures good form and presentation of the character, and is deeply connected with the history of the Chinese language itself.

After all, Chinese characters are an art form, and the rules of stroke order are especially important when it comes to writing Chinese calligraphy.

Understanding Chinese stroke order rules is also incredibly useful when trying to find less commonly used characters in dictionaries or via text prediction on your keyboard.

Ninchanese Blog

Tips and tricks to help you learn Chinese

Writing Chinese characters: The purpose

I think at one point everyone who starts learning Chinese asks themselves the same questions about writing Chinese:

With this article, I want to share a bit of my experience in writing characters and maybe a helpful additional way of learning Chinese. To be clear, I’m not talking about the art of Chinese Calligraphy but just casual hand-writing. Handwritten Chinese with a pen a piece of paper.

Do I need to learn to write Chinese characters?

Learning a language, in general, is split into 4 parts. Each with different importance: Listening, Speaking, Reading, and Writing. I think everyone would agree that Listening and Speaking are the most important. After that comes reading, and at the end is writing as the least important part. Also, if the language is similar to your mother-tongue, then writing and reading becomes just a byproduct, because you already can read and write the words, even if you don’t know the meaning.

The question if you need to learn to write Chinese characters is the most common one, and honestly, it’s not necessary to learn handwritten Chinese. But learning how to write Chinese characters can help and provide another supporting method to learn them if you are into writing.

The few positive attributes of writing Chinese characters:

Before jumping into the subject, let’s take a look at the reasons why you may not need to learn to write Chinese characters.

Why you might not need to learn how to write Chinese characters?

When is the best time to start learning to write Chinese characters?

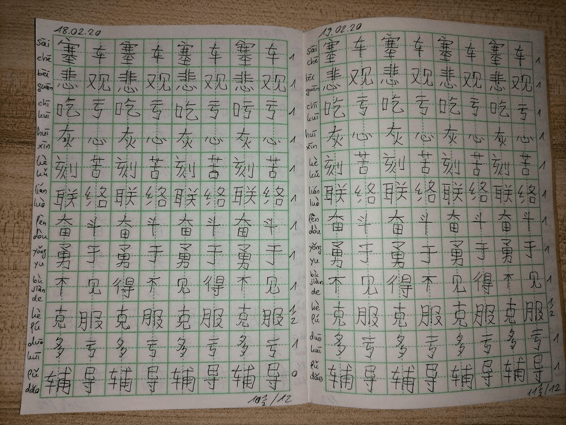

Since I started learning Chinese, I also started writing Chinese characters every day as an additional way to learn words, after the switch from pinyin only to Chinese characters. For me, all of the above points go very well together. Learning to write Chinese character reinforce my understanding of characters.

So, I would say this is also the best time to start writing Chinese characters: right from the beginning. Everyone has to go through the elementary pronunciation- and pinyin-only classes before entering the tough world of Chinese characters, so the best way is when everything goes hand-in-hand. But it’s also not too late to start with it if you are already on a higher level. You just need some patience, persistence, and a good learning strategy.

But since everyone learns differently, has their methods and is not necessarily that interested in the world of Chinese characters, this totally depends on your preferences.

🏮 Ninchanese is an incredible app for learning Chinese! 🏮

” I actually graduated from the University of Edinburgh with a MA in Chinese.

I’ve used Ninchanese daily, and it has helped me a lot! “

– Connor, Ninchanese User

Try Ninchanese, an award-winning method to learn Chinese today:

Start Learning Now

How do I start learning writing Chinese characters?

The material

When I started with hand-writing Chinese, I tried different methods to find what worked best for me.

So, first things first: Basically, what you need is just a pen, something to write on, some words you want to practice and a dictionary/app which can show you the stroke-orders and directions.

The plan

Sounds simple and easy but there are some factors you have to ask yourself:

And as mentioned above, it’s not about Calligraphy, but casual handwriting. So, don’t spend too much time and money in searching for the best pen and paper. In my opinion, that doesn’t matter that much; you just need to feel comfortable when writing. The only thing which has at least a small impact is the paper.

My own routine

For me, the paper affects a lot of those questions above. You’ll get that later, first I’ll show you my personal answers on the questions:

The role of the paper

To answer the other questions, at this point, the paper comes in:

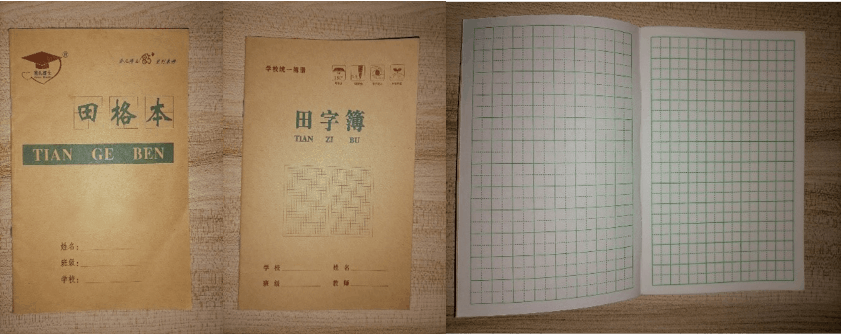

I’m using those small vocabulary-notebooks, which are exactly what I need:

Both of them are pretty much the same. It’s just different manufacturers, and the 田格本 had one row less than the 田字簿。

So, based on these notebooks, I decided to write one page every day, which answers the questions of how much time to spent and how many characters to write:

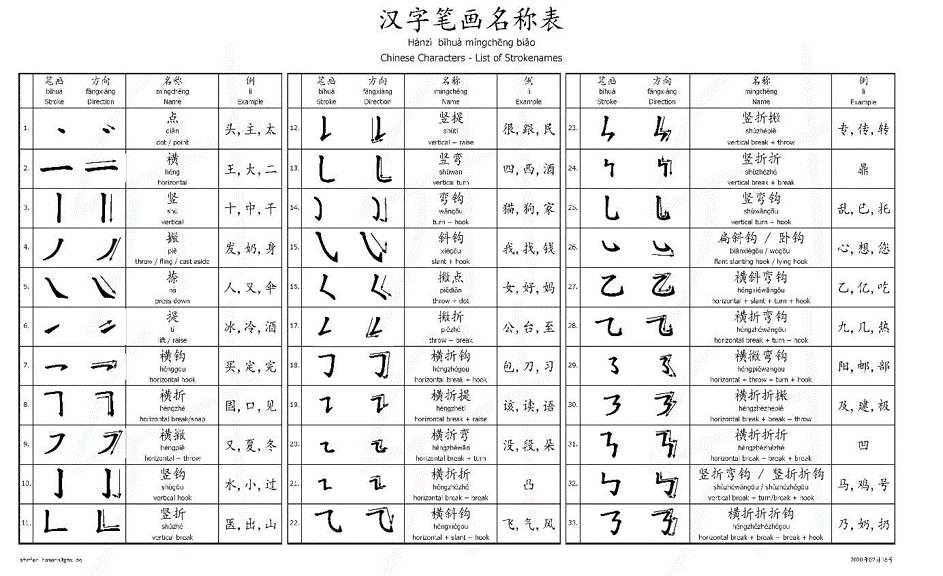

Does stroke order matter in chinese? The list of Strokenames of Chinese character

All types of strokes have names by themselves, but you don’t have to remember all of those. Even in casual Chinese language, these are rarely known. There are some which are also very rarely used, only in a few characters.

I picked this sheet up in the past for a class once and translated the names, so you can imagine where their names come from:

Writing Right-/Lefthanded:

You may have heard that the majority of Chinese people are right-handed. It’s a tradition to train left-handed people to use their right hand. So, why do I mention it? I am lefthanded, which leads to a minor problem when writing these characters.

When you look at the stroke orders and directions, these are defined rules and these essential when you write with an ink-pen or brush, because you have to press down and lift the pen at the end, so it leaves a specific line-thickness at the end or beginning.

When casually writing Chinese characters, a right-handed person would drag the pen in the direction he writes and leaves the words, but a left-handed person has to push the pen and would always smear his left-hand over the just written words. So, using a lot of ink will always result in a big mess, but it also feels very uncomfortable when you have to push a pen to create horizontal strokes (try to push a pen over paper, you’ll see). And here again, I have to mention it’s just about casual handwriting, so to feel comfortable writing Chinese characters, I write horizontal lines from right to left instead of the other direction.

A short personal story about that: One time in school, I had to write characters on the whiteboard in front of the teacher, and it was the first time I had to do that. So, I just wrote like I was comfortable with dragging horizontal lines from right to left. In the end, my teacher smiled and said that the written characters are 100% correct, but the way I wrote was not that accurate, and I explained that I knew but did so because I use my left hand, and it feels more comfortable that way. This was hard to understand for him, and it still is for a lot of (righthanded) people when I explain it.

Since that episode with the teacher, I’m still doing my writing-practice how I feel comfortable, but I also know the proper way, and whenever I have to write in front of a teacher, I’ll write how it is intended, even if it’s not comfortable for me.

So, saying that, I hope this article provides some useful tips and answers to some questions which prevented you from writing Chinese characters. It doesn’t take much, so why not just give it a try? Who knows, you may get the hang of it and it becomes a routine in your daily life.