How to write to in japanese

How to write to in japanese

How to Write in Japanese on your Keyboard

When you start learning Japanese, you want to be able to switch your keyboard to a different writing system from the Roman alphabet. To do so, you need to figure out and practice how to access the hiragana, katakana and kanji writing systems and use them properly. This is what this article is about.

Beforehand, especially if your computer is not a recent model, you should check that it can display Japanese characters correctly.

Activate the Japanese input option

On most computers bought outside of Japan, the (virtual) Japanese keyboard cannot be accessed by default. You therefore need to browse the options in order to display it next to your usual keyboard (English or other):

On Windows PC

The Microsoft operating system uses IME (Input Method Editor) as its input module for foreign languages including Japanese.

On Windows 8 or 7 (very similar procedure on Windows Vista or XP):

In the taskbar, a new icon is added to the list of languages. To switch from one input language to the other:

On Mac OS X

On Mac OS 10.10 Yosemite (very similar procedure on all Mac OS X):

In the menu bar, a new flag icon appears. To switch from one input language to the other:

Please note that Google has developed its own IME which you may use instead of the Microsoft IME.

On iPhone

In iOS 8 (the procedure has remained largely unchanged since the beginning):

To switch input languages, click the globe-shaped button (or leave it pressed to display the list) located to the left of the space bar.

Romaji writing guide

Using the QWERTY keyboard

To write in Japanese, the keyboard automatically switches to the native QWERTY format. Hence for some users, please mind that several letters change places.

If you’re not used to it, refer yourself to the featured image at the top of this article to find out the location of each key of the QWERTY keyboard as well as the location of commas, full stops, long vowels and other special characters.

It is of course possible to force the use of AZERTY in the settings. It is however, in our opinion, a better learning method to get used to this American system used in Japan.

You write phonetically using the Hepburn system. For example if you want to write “Kanpai” in Japanese, the editor takes charge and transcribes, as you write, your Roman characters into kana (かんぱい) and then kanji (乾杯) which you can change by using the space bar and the up and down arrow keys.

Alternatively, using a Japanese keyboard will allow you to write kana characters directly by using a specific key for each: this is called syllabic writing. The cost is approximately from 50 to 100 US dollars.

Specific features of the Japanese language

However there is more to the Japanese language than reaching a letter by pressing a key, and it is sometimes necessary to use special characters with a very specific display mode. Thus you will have to:

There is not, however, any built-in feature for furigana and using it requires very specific software.

Japanese fonts

Western operating systems generally turn out to offer a rather limited choice of Japanese types.

For the sake 🍶 of variety and in order to be able to use different font styles in Kana and kanji, you can download the desired patterns from such websites as FreeJapaneseFonts.

On iPhone

The difference between the two available keyboards is obvious:

This solution requires a little bit of practice but can prove very useful and fast once you have mastered the trick.

How to write the date in Japanese

Telling the date in Japanese is not awfully complicated. Here is a short summary of how to express the date in Japanese and how to refer to and pronounce the names of the days, months and years.

In order to say the date in Japanese, you can for example say 今日は2019年2月17日です。 Here are the elements of this sentence presented separately:

The order is reversed compared to Europe: the year comes first, then the month and finally the day; this is the “big endian” format, which is widely used in Asia.

What follows is a detailed account of each element in the sentence above.

The years in Japanese

Just mention the year concerned and then add the kanji 年 nen for year.

The Japanese will typically use the Gregorian calendar although they will also often use the Japanese one based on the reigns of Japanese emperors. Since May 2019, Japan has entered the 令和 reiwa imperial era. You will see this printed on tickets for example when you travel to Japan.

Here are the correspondences of the years:

| Japanese | Meaning | Gregorian calendar |

|---|---|---|

| 平成29年 | year 29 of the Heisei era | 2017 |

| 平成30年 | year 30 of the Heisei era | 2018 |

| 平成31年 | year 31 of the Heisei era | 2019 (From January to April) |

| 令和1年 | year 1 of the Reiwa era | 2019 (From May to December) |

| 令和2年 | year 2 of the Reiwa era | 2020 |

| 令和3年 | year 3 of the Reiwa era | 2021 |

| 令和4年 | year 4 of the Reiwa era | 2022 |

There is actually an application called Gengou Free to easily convert any year of the Gregorian calendar into its traditional Japanese counterpart.

The months in Japanese

It works in the same way for Japanese months: First write the number corresponding to the month concerned, then the kanji 月 gatsu. Thus:

The days of the week and of the month in Japanese

The days of the week

It should be mentioned that the week officially begins on Sunday rather than Monday.

The days of the month

They follow a simple rule (number + 日 nichi) but almost half of them are irregular! See the complete list below, with an asterisk after each irregular word:

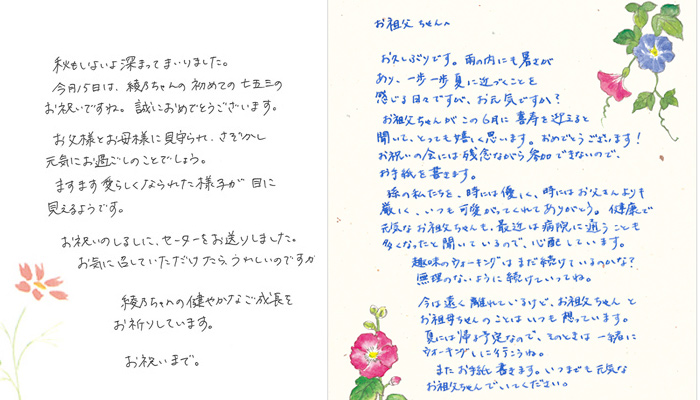

How To Write Letters In Japanese: An Introduction Pen Pal Besties for Life

Writing a letter in Japanese is quite the epic topic. It’s sadly not as easy as writing something, stuffing it in an envelope, stamping it, and sending it. Japanese letters require you to think about certain formalities, set expressions, styles of writing, and even relationships between you and the person you’re writing to. It’s so complicated and convoluted that even Japanese people will buy books on the subject so that they can «read up on» and study the latest letter writing rules. Don’t feel bad if you feel lost.

The goal of this article is to help you to understand Japanese letters. It will take a little more research and studying to be able to write a letter in Japanese, but I think I’ll be covering the difficult part. After reading this article, I want you to understand things like the relationship between you and the person you’re writing to, the format of a Japanese letter (both vertical and horizontal), how to write the address on the envelope, as well as the concept of «set expressions.» This will give you the tools to write a letter, make things less confusing, and eventually get you to the point where you should be able to piece together a Japanese letter on your own (resources included in the last section of this article).

Let’s get straight into the first thing you must think about even before you pick up that pen and paper. Wait, I mean, go to your keyboard and monitor, relationships.

Relationships: AKA Who Are You Writing To?

In Japanese, hierarchy is much more important than in many other countries. You have the senpai-kohai relationship. Then you have teacher vs. student, boss vs. minion, older people vs. younger people, and the list goes on and on. On top of this, relationship statuses change when you’re asking for a request, but this (and many other things) will depend on how close you are to the other person. Relationships, your closeness, and where you stand in the hierarchy of said relationship dictate how you act and speak with that other person. Of course, this carries over to letters as well.

I am going to simplify it a bit for you though. In general, there’s going to be three types of letters. They are:

Informal: Friends, Senpai, People below you

Neutral: Teachers, Friends you are requesting something of, Superiors

Formal: People you don’t know, Superiors you are requesting something of

You may have noticed some patterns here. Informal relationships are people of a similar age, aka people who are on the same hierarchy level as you. Then, there’s neutral (which is really just regular-polite level) which has teachers and other superiors whom you have at least a moderately close relationship with, though friends that you are requesting something of get bumped up to this rung (because you have to be nice if you’re asking for something). Lastly, there’s formal, which includes people you don’t have a close relationship with (people you don’t know), as well as superiors that you’re asking something of. Asking something of someone automatically bumps them up to the next rung, as a rule of thumb.

Of course, as long as you stay in the Neutral or Formal levels, you’ll probably always be okay, so that’s what I’ll be sticking with in these articles as well. Informal is informal, and doesn’t really need to follow so many of the rules that I’ll be laying out here during this series.

The Materials

Now that you know who you’re writing to, it’s time to figure out what materials you need to use. I think a lot of this is just common sense, but just in case it isn’t, I’ve summarized and simplified a list provided by the (excellent) textbook, Writing Letters In Japanese.

Once you’ve figured out your materials (based on who you’re writing to), it’s time to learn how to use these materials. Sadly, not all of it is as simple as you might think. There are rules, Smokey!

Japanese Letter Formatting Rules

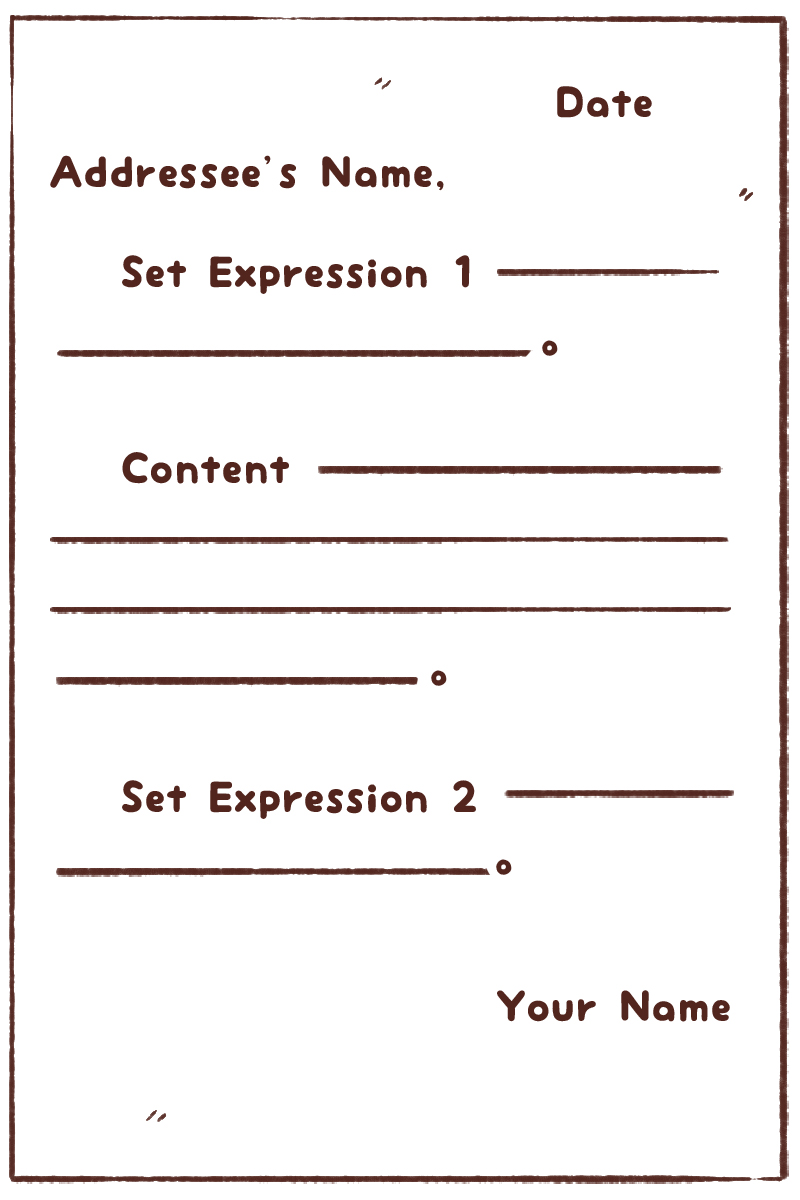

I will cover two types of letter: Vertical and Horizontal. This refers to how you’re writing your text. Does it go up to down or does it go right to left? Depending on which one you choose, there are a few differences you need to take note of.

Vertical Letters

These are the most personal. I suppose you’re putting a lot more work into this kind, because in general you’re writing them out by hand. Horizontal rule letters feel a little colder and less personal, though I think that’s changing. Usually, though, you can’t go wrong with a vertical letter, as it’s the standard style for letter writing in Japan.

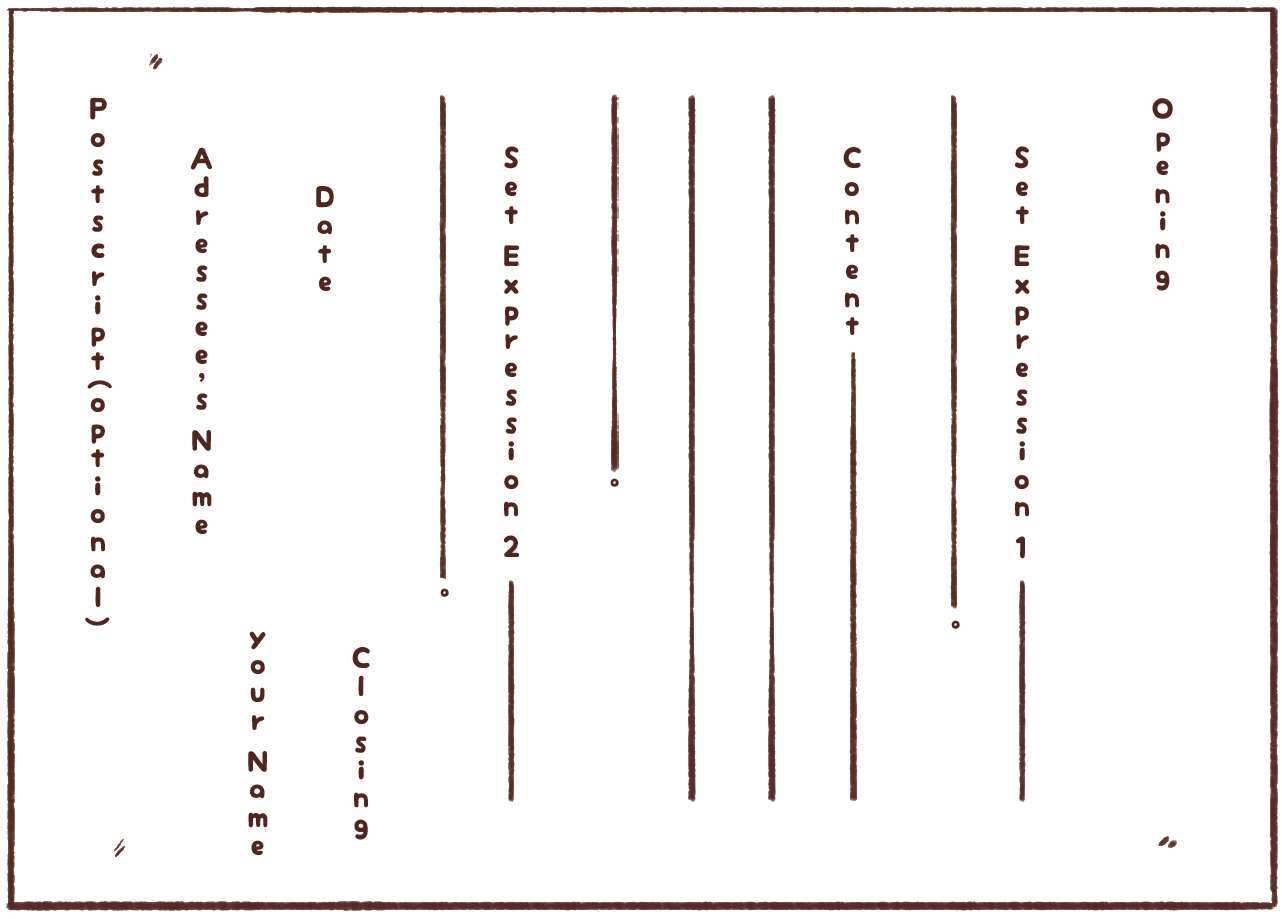

As you can see there are various parts, and the positioning of each is important.

Set Expression #1: Right at the beginning of the letter there should be a set expression. This could be one of many predetermined topics or phrases, which are usually about weather, the season, health of the addressee, and so on and so forth. Certain topics will have certain opening set expressions as well, but we’ll go more into that later.

Content: This is where you actually write your letter and say the things you want to say. Notice how this is the only non-predetermined section out of so many? It’s weird.

Set Expression #2: After you finish saying what you want to say, it’s time for another set expression. This will usually be about the addressee’s health or good wishes for them.

Date: This is written a little lower than the text to its right. Use the Japanese numeral system for vertical letters.

Your Name: This is where you write your name. Put it down to the bottom of the column.

Addressee’s Name: This goes to the left of the date and your name, but higher than the date, and lower than all the text to the right.

As you can see, there’s a lot to consider even before you write any content. Luckily, horizontal letters are a lot simpler.

Horizontal Letters

Generally used in business sorts of situations, horizontal letters are mostly typed out and a lot simpler.

Date: Goes in the top right. It’s written using Arabic numerals since it’s being written horizontally. 12月25日, for example.

Addressee’s Name: This is where you put the name of the person you’re writing to. As with all letters, don’t forget their name honorific!

Set Expression #1: Here’s where the first set expression will go.

Content: This is where the content of your letter will go.

Set Expression #2: One more set expression for the addressee’s well being and health.

Your Name: This is where you sign your name, horizontally. Might be good to sign it with a pen instead of with the word processor, just to be a little more polite.

Horizontal letters are easier, but they can be considered rude if you send them in the wrong situations. Of course, email is a whole other thing (it’s all horizontal there), and I think it’s causing the mindset to shift a bit on this. Still, though, vertical is the default go-to for writing letters (especially by hand), so be sure learn about it even though this one is easier.

Envelopes And Addresses

The address system in Japan is quite different from America and much of the rest of the world. You’ll want to know about that before sending a letter, otherwise it may not get to the desired location (that being said, the Japanese postal system is baller). Once you know the address, though, there are some rules as to where you should be putting the mailing address, return address, and stamp.

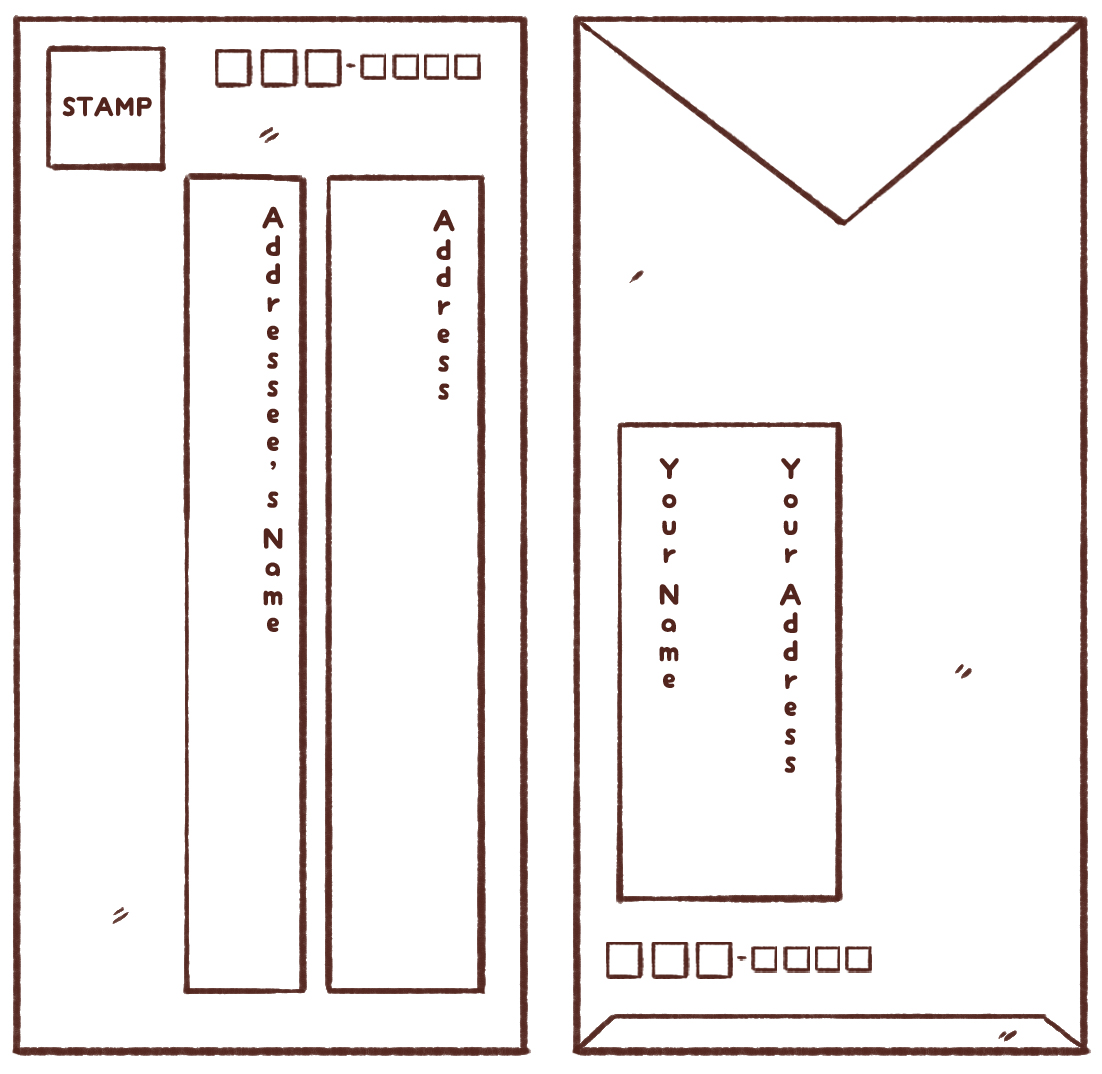

Vertical Envelopes

This is the tall type envelope which you will often see in Japan. It’s good for vertically written letters, as you can crease your letter parallel to the lines you’re writing.

As you can see there are a few different things compared to the envelopes you might be used to. First off, you’ll want to put the postal code in boxes provided. Then, on the front of the envelope, you’ll want to put the address on the right side (written vertically) and the addressee’s name on the left, written in slightly bigger letters than the address to help differentiate. On the flap side of the envelope you should write the return address. Your name and address should go on the left side in the same format as the addressee’s name and address (though size isn’t going to matter as much), and your postal code should go in the boxes if they’re provided.

Horizontal Envelopes

With horizontal envelopes, there are a couple ways to do it.

A lot of the rules carry over from vertical envelopes, so this should be a little easier. So what about when you’re sending a letter to Japan?

Sending Letters To Japan From Overseas

When you are sending a letter to Japan from outside of Japan, you can write the address in romaji (though Japanese is preferred, if you can), and write it in the format that’s normally accepted in your country. Just be sure to write «JAPAN» at the bottom of the addressee’s address so they know to send it there!

Opening Set Expressions

This is perhaps the most difficult section of all when it comes to writing letters in Japanese. Luckily, these are set expressions, meaning you can just look them up, use them, and gone on with your life. The tricky part comes when you have to come up with some of your own (in certain specific situations), though we’re going to just ignore that for now.

The first set of set expressions is the one that comes before the start of your actual content. It generally has to do with weather, the season, or health of the addressee. There are expressions for each month, season, as well as different opening greetings for various inquisitions on the addressee’s health. Here are some examples, though there are many more set expressions worth knowing (or knowing where to find, which I’ll go over at the end).

January:

Spring:

August:

December:

Health Related:

Writing A Reply To A Letter

These set expressions are only a drop in the bucket. There are at least several set expressions for each month, season, and situation, and there are probably more out there. The thing about set expressions is you are expected to write with said set expressions, otherwise your letter isn’t going to come off as polite. While creativity is encouraged in Western letters, using some set expression rules is more important in Japanese, which makes things both harder and easier.

Closing Set Expressions

After your main content you have to go back into set expressions. There are fewer of these, but it’s still basically the same thing as the opening ones. Here are some examples:

Making A Request

Give My regards

Good Health

Request A Reply

I think closing set expressions are a little simpler than the opening ones, but they’re all basically the same thing and you’ll see the same ones over and over a lot.

Where To Go From Here?

So as you can see, writing letters in Japanese is a big ordeal, though once you learn all the rules and do a little practice it’s not all that bad. In fact, it’s very set in stone, meaning that as long as you follow the rules you’ll be able to write a great letter in Japanese.

The next step, I think, is to take a look at examples. Writing letters in Japanese definitely takes an intermediate or advanced knowledge of the language, so if you possess said knowledge and want an English textbook, I’d recommend Writing Letters In Japanese. It contains plenty of example letters as well as lessons going over all of them to help you get your letter writing skills up to snuff. Alternatively, if you’re fairly advanced in Japanese, the Japanese website Midori-Japan’s 手紙の書き方 will do the trick. This site includes many example letters for many different and often specific situations as well as a list of set expressions that you can pull from. Basically, everything you need to template out a proper Japanese letter.

I hope this article and those sources help you to get started writing letters in Japanese! It’s a crazy letter writing world over there, but once you get your foot in the proverbial letter-writing door it become easier. I want to write more on this topic soon, including examples for plenty of different letter-writing situations, but we’ll see if it’s next week or a week in the future to come. Writing letters in Japanese is a huge topic, as I think everyone has come to understand so long as you’ve read to this point.

Category: The Writing System

Chapter Overview

The Scripts

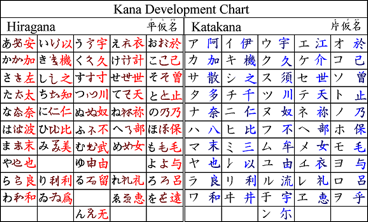

Japanese consists of two scripts (referred to as kana) called Hiragana and Katakana, which are two versions of the same set of sounds in the language. Hiragana and Katakana consist of a little less than 50 “letters”, which are actually simplified Chinese characters adopted to form a phonetic script.

Chinese characters, called Kanji in Japanese, are also heavily used in the Japanese writing. Most of the words in the Japanese written language are written in Kanji (nouns, verbs, adjectives). There exists over 40,000 Kanji where about 2,000 represent over 95% of characters actually used in written text. There are no spaces in Japanese so Kanji is necessary in distinguishing between separate words within a sentence. Kanji is also useful for discriminating between homophones, which occurs quite often given the limited number of distinct sounds in Japanese.

Hiragana is used mainly for grammatical purposes. We will see this as we learn about particles. Words with extremely difficult or rare Kanji, colloquial expressions, and onomatopoeias are also written in Hiragana. It’s also often used for beginning Japanese students and children in place of Kanji they don’t know.

While Katakana represents the same sounds as Hiragana, it is mainly used to represent newer words imported from western countries (since there are no Kanji associated with words based on the roman alphabet). The next three sections will cover Hiragana, Katakana, and Kanji.

Intonation

As you will find out in the next section, every character in Hiragana (and the Katakana equivalent) corresponds to a [vowel] or [consonant + vowel] syllable sound with the single exception of the 「ん」 and 「ン」 characters (more on this later). This system of letter for each syllable sound makes pronunciation absolutely clear with no ambiguities. However, the simplicity of this system does not mean that pronunciation in Japanese is simple. In fact, the rigid structure of the fixed syllable sound in Japanese creates the challenge of learning proper intonation.

Intonation of high and low pitches is a crucial aspect of the spoken language. For example, homophones can have different pitches of low and high tones resulting in a slightly different sound despite sharing the same pronunciation. The biggest obstacle for obtaining proper and natural sounding speech is incorrect intonation. Many students often speak without paying attention to the correct enunciation of pitches making speech sound unnatural (the classic foreigner’s accent). It is not practical to memorize or attempt to logically create rules for pitches, especially since it can change depending on the context or the dialect. The only practical approach is to get the general sense of pitches by mimicking native Japanese speakers with careful listening and practice.

Hiragana

Hiragana is the basic Japanese phonetic script. It represents every sound in the Japanese language. Therefore, you can theoretically write everything in Hiragana. However, because Japanese is written with no spaces, this will create nearly indecipherable text.

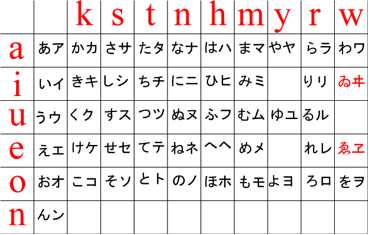

Here is a table of Hiragana and similar-sounding English consonant-vowel pronunciations. It is read up to down and right to left, which is how most Japanese books are written. In Japanese, writing the strokes in the correct order and direction is important, especially for Kanji. Because handwritten letters look slightly different from typed letters (just like how ‘a’ looks totally different when typed), you will want to use a resource that uses handwritten style fonts to show you how to write the characters (see below for links). I must also stress the importance of correctly learning how to pronounce each sound. Since every word in Japanese is composed of these sounds, learning an incorrect pronunciation for a letter can severely damage the very foundation on which your pronunciation lies.

| n | w | r | y | m | h | n | t | s | k | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ん (n) | わ | ら | や | ま | は | な | た | さ | か | あ | a |

| ゐ* | り | み | ひ | に | ち (chi) | し (shi) | き | い | i | ||

| る | ゆ | む | ふ (fu) | ぬ | つ (tsu) | す | く | う | u | ||

| ゑ* | れ | め | へ | ね | て | せ | け | え | e | ||

| を (o) | ろ | よ | も | ほ | の | と | そ | こ | お | o |

You can listen to the pronunciation for each character by clicking on it in chart. If your browser doesn’t support audio, you can also download them at http://www.guidetojapanese.org/audio/basic_sounds.zip. There are also other free resources with audio samples.

Hiragana is not too tough to master or teach and as a result, there are a variety of web sites and free programs that are already available on the web. I also suggest recording yourself and comparing the sounds to make sure you’re getting it right.

When practicing writing Hiragana by hand, the important thing to remember is that the stroke order and direction of the strokes matter. There, I underlined, italicized, bolded, and highlighted it to boot. Trust me, you’ll eventually find out why when you read other people’s hasty notes that are nothing more than chicken scrawls. The only thing that will help you is that everybody writes in the same order and so the “flow” of the characters is fairly consistent. I strongly recommend that you pay close attention to stroke order from the beginning starting with Hiragana to avoid falling into bad habits. While there are many tools online that aim to help you learn Hiragana, the best way to learn how to write it is the old fashioned way: a piece of paper and pen/pencil. Below are handy PDFs for Hiragana writing practice.

※ As an aside, an old Japanese poem called 「いろは」 was often used as the base for ordering of Hiragana until recent times. The poem contains every single Hiragana character except for 「ん」 which probably did not exist at the time it was written. You can check out this poem for yourself in this wikipedia article. As the article mentions, this order is still sometimes used in ordering lists so you may want to spend some time checking it out.

The Muddied Sounds

Once you memorize all the characters in Hiragana, there are still some additional sounds left to be learned. There are five more consonant sounds that are written by either affixing two tiny lines similar to a double quotation mark called dakuten (濁点) or a tiny circle called handakuten (半濁点). This essentially creates a “muddy” or less clipped version of the consonant (technically called a voiced consonant or 「濁り」, which literally means to become muddy).

All the voiced consonant sounds are shown in the table below.

| p | b | d | z | g | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ぱ | ば | だ | ざ | が | a |

| ぴ | び | ぢ (ji) | じ (ji) | ぎ | i |

| ぷ | ぶ | づ (dzu) | ず | ぐ | u |

| ぺ | べ | で | ぜ | げ | e |

| ぽ | ぼ | ど | ぞ | ご | o |

The Small 「や」、「ゆ」、and 「よ」

You can also combine a consonant with a / ya / yu / yo / sound by attaching a small 「や」、「ゆ」、or 「よ」 to the / i / vowel character of each consonant.

| p | b | j | g | r | m | h | n | c | s | k | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ぴゃ | びゃ | じゃ | ぎゃ | りゃ | みゃ | ひゃ | にゃ | ちゃ | しゃ | きゃ | ya |

| ぴゅ | びゅ | じゅ | ぎゅ | りゅ | みゅ | ひゅ | にゅ | ちゅ | しゅ | きゅ | yu |

| ぴょ | びょ | じょ | ぎょ | りょ | みょ | ひょ | にょ | ちょ | しょ | きょ | yo |

The Small 「つ」

A small 「つ」 is inserted between two characters to carry the consonant sound of the second character to the end of the first. For example, if you inserted a small 「つ」 between 「び」 and 「く」 to make 「びっく」, the / k / consonant sound is carried back to the end of the first character to produce “bikku”. Similarly, 「はっぱ」 becomes “happa”, 「ろっく」 becomes “rokku” and so on and so forth.

Examples

The Long Vowel Sound

Whew! You’re almost done. In this last portion, we will go over the long vowel sound which is simply extending the duration of a vowel sound. You can extend the vowel sound of a character by adding either 「あ」、「い」、or 「う」 depending on the vowel in accordance to the following chart.

| Vowel Sound | Extended by |

|---|---|

| / a / | あ |

| / i / e / | い |

| / u / o / | う |

For example, if you wanted to create an extended vowel sound from 「か」, you would add 「あ」 to create 「かあ」. Other examples would include: 「き → きい」, 「く → くう」, 「け → けい」, 「こ → こう」, 「さ → さあ」 and so on. The reasoning for this is quite simple. Try saying 「か」 and 「あ」 separately. Then say them in succession as fast as you can. You’ll notice that soon enough, it sounds like you’re dragging out the / ka / for a longer duration than just saying / ka / by itself. When pronouncing long vowel sounds, try to remember that they are really two sounds merged together.

It’s important to make sure you hold the vowel sound long enough because you can be saying things like “here” (ここ) instead of “high school” (こうこう) or “middle-aged lady” (おばさん) instead of “grandmother” (おばあさん) if you don’t stretch it out correctly!

Examples

There are rare exceptions where an / e / vowel sound is extended by adding 「え」 or an / o / vowel sound is extended by 「お」. Some examples of this include 「おねえさん」、「おおい」、and 「おおきい」. Pay careful attention to these exceptions but don’t worry, there aren’t too many of them.

Hiragana Practice Exercises

Fill in the Hiragana Chart

Though I already mentioned that there are many sites and helper programs for learning Hiragana, I figured I should put in some exercises of my own in the interest of completeness. I’ve removed the obsolete characters since you won’t need to know them. I suggest playing around with this chart and a scrap piece of paper to test your knowledge of Hiragana.

Click on the flip link to show or hide each character.

| n | w | r | y | m | h | n | t | s | k | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ん flip | わ flip | ら flip | や flip | ま flip | は flip | な flip | た flip | さ flip | か flip | あ flip | a |

| り flip | み flip | ひ flip | に flip | ち flip | し flip | き flip | い flip | i | |||

| る flip | ゆ flip | む flip | ふ flip | ぬ flip | つ flip | す flip | く flip | う flip | u | ||

| れ flip | め flip | へ flip | ね flip | て flip | せ flip | け flip | え flip | e | |||

| を flip | ろ flip | よ flip | も flip | ほ flip | の flip | と flip | そ flip | こ flip | お flip | o |

Hiragana Writing Practice

In this section, we will practice writing some words in Hiragana. This is the only part of this guide where we will be using the English alphabet to represent Japanese sounds. I’ve added bars between each letter to prevent the ambiguities that is caused by romaji such as “un | yo” vs “u | nyo”. Don’t get too caught up in the romaji spellings. Remember, the whole point is to test your aural memory with Hiragana. I hope to replace this with sound in the future to remove the use of romaji altogether.

Hiragana Writing Exercise 1

Sample: ta | be | mo | no = たべもの

| 1. ku | ru | ma | = | くるま |

| 2. a | shi | ta | = | あした |

| 3. ko | ku | se | ki | = | こくせき |

| 4. o | su | shi | = | おすし |

| 5. ta | be | ru | = | たべる |

| 6. wa | ka | ra | na | i | = | わからない |

| 7. sa | zu | ke | ru | = | さずける |

| 8. ri | ku | tsu | = | りくつ |

| 9. ta | chi | yo | mi | = | たちよみ |

| 10. mo | no | ma | ne | = | ものまね |

| 11. hi | ga | e | ri | = | ひがえり |

| 12. pon | zu | = | ぽんず |

| 13. hi | ru | me | shi | = | ひるめし |

| 14. re | ki | shi | = | れきし |

| 15. fu | yu | ka | i | = | ふゆかい |

More Hiragana Writing Practice

Now we’re going to move on to practice writing Hiragana with the small 「や」、「ゆ」、「よ」 、and the long vowel sound. For the purpose of this exercise, I will denote the long vowel sound as “-” and leave you to figure out which Hiragana to use based on the letter preceding it.

Hiragana Writing Exercise 2

Sample: jyu | gyo- = じゅぎょう

| 1. nu | ru | i | o | cha | = | ぬるいおちゃ |

| 2. kyu- | kyo | ku | = | きゅうきょく |

| 3. un | yo-| jyo- | ho- | = | うんようじょうほう |

| 4. byo- | do- | = | びょうどう |

| 5. jyo- | to- | shu | dan | = | じょうとうしゅだん |

| 6. gyu- | nyu- | = | ぎゅうにゅう |

| 7. sho- | rya | ku | = | しょうりゃく |

| 8. hya | ku | nen | ha | ya | i | = | ひゃくねんはやい |

| 9. so | tsu | gyo- | shi | ki | = | そつぎょうしき |

| 10. to- | nyo- | byo- | = | とうにょうびょう |

| 11. mu | ryo- | = | むりょう |

| 12. myo- | ji | = | みょうじ |

| 13. o | ka- | san | = | おかあさん |

| 14. ro- | nin | = | ろうにん |

| 15. ryu- | ga | ku | se | i | = | りゅうがくせい |

Hiragana Reading Practice

Now let’s practice reading some Hiragana. I want to particularly focus on correctly reading the small 「つ」. Remember to not get too caught up in the unavoidable inconsistencies of romaji. The point is to check whether you can figure out how it’s supposed to sound in your mind.

Hiragana Reading Exercise

| 1. きゃっかんてき | = | kyakkanteki |

| 2. はっぴょうけっか | = | happyoukekka |

| 3. ちょっかん | = | chokkan |

| 4. ひっし | = | hisshi |

| 5. ぜったい | = | zettai |

| 6. けっちゃく | = | ketchaku |

| 7. しっぱい | = | shippai |

| 8. ちゅうとはんぱ | = | chuutohanpa |

| 9. やっかい | = | yakkai |

| 10. しょっちゅう | = | shotchuu |

Katakana

As mentioned before, Katakana is mainly used for words imported from foreign languages. It can also be used to emphasize certain words similar to the function of italics. For a more complete list of usages, refer to the Wikipedia entry on katakana.

Katakana represents the same set of phonetic sounds as Hiragana except all the characters are different. Since foreign words must fit into this limited set of [consonants+vowel] sounds, they undergo many radical changes resulting in instances where English speakers can’t understand words that are supposed to be derived from English! As a result, the use of Katakana is extremely difficult for English speakers because they expect English words to sound like… well… English. Instead, it is better to completely forget the original English word, and treat the word as an entirely separate Japanese word, otherwise you can run into the habit of saying English words with English pronunciations (whereupon a Japanese person may or may not understand what you are saying).

| n | w | r | y | m | h | n | t | s | k | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ン (n) | ワ | ラ | ヤ | マ | ハ | ナ | タ | サ | カ | ア | a |

| ヰ* | リ | ミ | ヒ | ニ | チ (chi) | シ (shi) | キ | イ | i | ||

| ル | ユ | ム | フ (fu) | ヌ | ツ (tsu) | ス | ク | ウ | u | ||

| ヱ* | レ | メ | ヘ | ネ | テ | セ | ケ | エ | e | ||

| ヲ* (o) | ロ | ヨ | モ | ホ | ノ | ト | ソ | コ | オ | o |

* = obsolete or rarely used

Katakana is significantly tougher to master compared to Hiragana because it is only used for certain words and you don’t get nearly as much practice as you do with Hiragana. To learn the proper stroke order (and yes, you need to), here is a link to practice sheets for Katakana.

Also, since Japanese doesn’t have any spaces, sometimes the symbol 「・」 is used to show the spaces like 「ロック・アンド・ロール」 for “rock and roll”. Using the symbol is completely optional so sometimes nothing will be used at all.

The Long Vowel Sound

Long vowels have been radically simplified in Katakana. Instead of having to muck around thinking about vowel sounds, all long vowel sounds are denoted by a simple dash like so: ー.

Examples

The Small 「ア、イ、ウ、エ、オ」

Due to the limitations of the sound set in Hiragana, some new combinations have been devised over the years to account for sounds that were not originally in Japanese. Most notable is the lack of the / ti / di / and / tu / du / sounds (because of the / chi / tsu / sounds), and the lack of the / f / consonant sound except for 「ふ」. The / sh / j / ch / consonants are also missing for the / e / vowel sound. The decision to resolve these deficiencies was to add small versions of the five vowel sounds. This has also been done for the / w / consonant sound to replace the obsolete characters. In addition, the convention of using the little double slashes on the 「ウ」 vowel (ヴ) with the small 「ア、イ、エ、オ」 to designate the / v / consonant has also been established but it’s not often used probably due to the fact that Japanese people still have difficulty pronouncing / v /. For instance, while you may guess that “volume” would be pronounced with a / v / sound, the Japanese have opted for the easier to pronounce “bolume” (ボリューム). In the same way, vodka is written as “wokka” (ウォッカ) and not 「ヴォッカ」. You can write “violin” as either 「バイオリン」 or 「ヴァイオリン」. It really doesn’t matter however because almost all Japanese people will pronounce it with a / b / sound anyway. The following table shows the added sounds that were lacking with a highlight. Other sounds that already existed are reused as appropriate.

| v | w | f | ch | d | t | j | sh | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ヴァ | ワ | ファ | チャ | ダ | タ | ジャ | シャ | a |

| ヴィ | ウィ | フィ | チ | ディ | ティ | ジ | シ | i |

| ヴ | ウ | フ | チュ | ドゥ | トゥ | ジュ | シュ | u |

| ヴェ | ウェ | フェ | チェ | デ | テ | ジェ | シェ | e |

| ヴォ | ウォ | フォ | チョ | ド | ト | ジョ | ショ | o |

Some examples of words in Katakana

Translating English words into Japanese is a knack that requires quite a bit of practice and luck. To give you a sense of how English words become “Japanified”, here are a few examples of words in Katakana. Sometimes the words in Katakana may not even be correct English or have a different meaning from the English word it’s supposed to represent. Of course, not all Katakana words are derived from English.

| English | Japanese |

|---|---|

| America | アメリカ |

| Russia | ロシア |

| cheating | カンニング (cunning) |

| tour | ツアー |

| company employee | サラリーマン (salary man) |

| Mozart | モーツァルト |

| car horn | クラクション (klaxon) |

| sofa | ソファ or ソファー |

| Halloween | ハロウィーン |

| French fries | フライドポテト (fried potato) |

Katakana Practice Exercises

Fill in the Katakana Chart

Here is the katakana chart you can use to help test your memory. 「ヲ」 has been removed since you’ll probably never need it.

Click on the flip link to show or hide each character.

| n | w | r | y | m | h | n | t | s | k | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ン flip | ワ flip | ラ flip | ヤ flip | マ flip | ハ flip | ナ flip | タ flip | サ flip | カ flip | ア flip | a |

| リ flip | ミ flip | ヒ flip | ニ flip | チ flip | シ flip | キ flip | イ flip | i | |||

| ル flip | ユ flip | ム flip | フ flip | ヌ flip | ツ flip | ス flip | ク flip | ウ flip | u | ||

| レ flip | メ flip | ヘ flip | ネ flip | テ flip | セ flip | ケ flip | エ flip | e | |||

| ロ flip | ヨ flip | モ flip | ホ flip | ノ flip | ト flip | ソ flip | コ flip | オ flip | o |

Katakana Writing Practice

Here, we will practice writing some words in Katakana. Plus, you’ll get a little taste of what foreign words sound like in Japanese.

Katakana Writing Exercise 1

Sample: ta | be | mo | no = タベモノ

| 1. pan | = | パン |

| 2. kon | pyu- | ta | = | コンピュータ |

| 3. myu- | ji | ka | ru | = | ミュージカル |

| 4. u- | man | = | ウーマン |

| 5 he | a | pi- | su | = | ヘアピース |

| 6. nu- | do | = | ヌード |

| 7. me | nyu- | = | メニュー |

| 8. ro- | te- | shon | = | ローテーション |

| 9. ha | i | kin | gu | = | ハイキング |

| 10. kyan | se | ru | = | キャンセル |

| 11. ha | ne | mu-n | | = | ハネムーン |

| 12. ku | ri | su | ma | su | tsu | ri- | = | クリスマスツリー |

| 13. ra | i | to | = | ライト |

| 14. na | i | to | ge- | mu | = | ナイトゲーム |

More Katakana Writing Practice

This Katakana writing exercise includes all the irregular sounds that don’t exist in Hiragana.

Katakana Writing Exercise 2

| 1. e | i | zu | wi | ru | su | = | エイズウイルス |

| 2. no- | su | sa | i | do | = | ノースサイド |

| 3. in | fo | me- | shon | = | インフォメーション |

| 4. pu | ro | je | ku | to | = | プロジェクト |

| 5. fa | su | to | fu- | do | = | ファストフード |

| 6. she | ru | su | ku | ri | pu | to | = | シェルスクリプト |

| 7. we- | to | re | su | = | ウェートレス |

| 8. ma | i | ho- | mu | = | マイホーム |

| 9. chi- | mu | wa- | ku | = | チームワーク |

| 10. mi | ni | su | ka- | to | = | ミニスカート |

| 11. re- | za- | di | su | ku | = | レーザーディスク |

| 12. chen | ji | = | チェンジ |

| 13. re | gyu | ra- | = | レギュラー |

| 14. u | e | i | to | ri | fu | tin | gu | = | ウエイトリフティング |

Changing English words to katakana

Just for fun, let’s try figuring out the katakana for some English words. I’ve listed some common patterns below but they are only guidelines and may not apply for some words.

As you know, since Japanese sounds almost always consist of consonant-vowel pairs, any English words that deviate from this pattern will cause problems. Here are some trends you may have noticed.

If you’ve seen the move “Lost in Translation”, you know that / l / and / r / are indistinguishable.

If you have more than one vowel in a row or a vowel sound that ends in / r /, it usually becomes a long vowel sound.

Abrupt cut-off sounds usually denoted by a / t / or / c / employ the small 「ッ」.

Any word that ends in a consonant sound requires another vowel to complete the consonant-vowel pattern. (Except for “n” and “m” for which we have 「ン」)

For “t” and “d”, it’s usually “o”. For everything else, it’s usually “u”.

English to Katakana Exercise

Sample: Europe = ヨーロッパ

| 1. check | = | チェック |

| 2. violin | = | バイオリン |

| 3. jet coaster (roller coaster) | = | ジェットコースター |

| 4. window shopping | = | ウィンドーショッピング |

| 5. salsa | = | サルサ |

| 6. hotdog | = | ホットドッグ |

| 7. suitcase | = | スーツケース |

| 8. kitchen | = | キッチン |

| 9. restaurant | = | レストラン |

| 10. New York | = | ニューヨーク |

Kanji

What is Kanji?

In Japanese, nouns and stems of adjectives and verbs are almost all written in Chinese characters called Kanji. Adverbs are also fairly frequently written in Kanji as well. This means that you will need to learn Chinese characters to be able to read most of the words in the language. (Children’s books or any other material where the audience is not expected to know a lot of Kanji is an exception to this.) Not all words are always written in Kanji however. For example, while the verb “to do” technically has a Kanji associated with it, it is always written in Hiragana.

This guide begins using Kanji from the beginning to help you read “real” Japanese as quickly as possible. Therefore, we will go over some properties of Kanji and discuss some strategies of learning it quickly and efficiently. Mastering Kanji is not easy but it is by no means impossible. The biggest part of the battle is mastering the skills of learning Kanji and time. In short, memorizing Kanji past short-term memory must be done with a great deal of study and, most importantly, for a long time. And by this, I don’t mean studying five hours a day but rather reviewing how to write a Kanji once every several months until you are sure you have it down for good. This is another reason why this guide starts using Kanji right away. There is no reason to dump the huge job of learning Kanji at the advanced level. By studying Kanji along with new vocabulary from the beginning, the immense job of learning Kanji is divided into small manageable chunks and the extra time helps settle learned Kanji into permanent memory. In addition, this will help you learn new vocabulary, which will often have combinations of Kanji you already know. If you start learning Kanji later, this benefit will be wasted or reduced.

Learning Kanji

All the resources you need to begin learning Kanji are on the web for free. You can use dictionaries online such as Jim Breen’s WWWJDIC or jisho.org. They both have great Kanji dictionaries and stroke order diagrams for most Kanji. Especially for those who are just starting to learn, you will want to repeatedly write out each Kanji to memorize the stroke order. Another important skill is learning how to balance the character so that certain parts are not too big or small. So make sure to copy the characters as close to the original as possible. Eventually, you will naturally develop a sense of the stroke order for certain types of characters allowing you to bypass the drilling stage. All the Kanji used in this guide can be easily looked up by copying and pasting to an online dictionary.

Reading Kanji

Almost every character has two different readings called 音読み (おんよみ) and 訓読み(くんよみ). 音読み is the original Chinese reading while 訓読み is the Japanese reading. Kanji that appear in a compound or 熟語 is usually read with 音読み while one Kanji by itself is usually read with 訓読み. For example, 「力」(ちから) is read with the 訓読み while the same character in a compound word such as 「能力」 is read with the 音読み (which is 「りょく」 in this case).

Certain characters (especially the most common ones) can have more than one 音読み or 訓読み. For example, in the word 「怪力」, 「力」 is read here as 「りき」 and not 「りょく」. Certain compound words also have special readings that have nothing to do with the readings of the individual characters. These readings must be individually memorized. Thankfully, these readings are few and far in between.

訓読み is also used in adjectives and verbs in addition to the stand-alone characters. These words often have a string of kana (called okurigana) that come attached to the word. This is so that the reading of the Chinese character stays the same even when the word is conjugated to different forms. For example, the past form of the verb 「食べる」 is 「食べた」. Even though the verb has changed, the reading for 「食」 remain untouched. (Imagine how difficult things could get if readings for Kanji changed with conjugation or even worse, if the Kanji itself changed.) Okurigana also serves to distinguish between intransitive and transitive verbs (more on this later).

Another concept that is difficult to grasp at first is that the actual readings of Kanji can change slightly in a compound word to make the word easier to say. The more common transformations include the / h / sounds changing to either / b / or / p / sounds or 「つ」 becoming 「っ」. Examples include: 「一本」、「徹底」、and 「格好」.

Yet another fun aspect of Kanji you’ll run into are words that practically mean the same thing and use the same reading but have different Kanji to make just a slight difference in meaning. For example 「聞く」(きく) means to listen and so does 「聴く」(きく). The only difference is that 「聴く」 means to pay more attention to what you’re listening to. For example, listening to music almost always prefers 「聴く」 over 「聞く」. 「聞く」 can also mean ‘to ask’, as well as, “to hear” but 「訊く」(きく) can only mean “to ask”. Yet another example is the common practice of writing 「見る」 as 「観る」 when it applies to watching a show such as a movie. Yet another interesting example is 「書く」(かく) which means “to write” while 描く (かく) means “to draw”. However, when you’re depicting an abstract image such as a scene in a book, the reading of the same word 「描く」 becomes 「えがく」. There’s also the case where the meaning and Kanji stays the same but can have multiple readings such as 「今日」 which can be either 「きょう」、「こんじつ」, or 「こんにち」. In this case, it doesn’t really matter which reading you choose except that some are preferred over others in certain situations.

Finally, there is one special character 々 that is really not a character. It simply indicates that the previous character is repeated. For example, 「時時」、「様様」、「色色」、「一一」 can and usually are written as 「時々」、「様々」、「色々」、「一々」.

In addition to these “features” of Kanji, you will see a whole slew of delightful perks and surprises Kanji has for you as you advance in Japanese. You can decide for yourself if that statement is sarcasm or not. However, don’t be scared into thinking that Japanese is incredibly hard. Most of the words in the language usually only have one Kanji associated with it and a majority of Kanji do not have more than two types of readings.

Why Kanji?

Some people may think that the system of using separate, discrete symbols instead of a sensible alphabet is overly complicated. In fact, it might not have been a good idea to adopt Chinese into Japanese since both languages are fundamentally different in many ways. But the purpose of this guide is not to debate how the language should work but to explain why you must learn Kanji in order to learn Japanese. And by this, I mean more than just saying, “That’s how it’s done so get over it!”.

You may wonder why Japanese didn’t switch from Chinese to romaji to do away with having to memorize so many characters. In fact, Korea adopted their own alphabet for Korean to greatly simplify their written language with great success. So why shouldn’t it work for Japanese? I think anyone who has learned Japanese for a while can easily see why it won’t work. At any one time, when you convert typed Hiragana into Kanji, you are presented with almost always at least two choices (two homophones) and sometimes even up to ten. (Try typing “kikan”). The limited number of set sounds in Japanese makes it hard to avoid homophones. Compare this to the Korean alphabet which has 14 consonants and 10 vowels. Any of the consonants can be matched to any of the vowels giving 140 sounds. In addition, a third and sometimes even fourth consonant can be attached to create a single letter. This gives over 1960 sounds that can be created theoretically. (The number of sounds that are actually used is actually much less but it’s still much larger than Japanese.)

Since you want to read at a much faster rate than you talk, you need some visual cues to instantly tell you what each word is. You can use the shape of words in English to blaze through text because most words have different shapes. Try this little exercise: Hi, enve thgouh all teh wrods aer seplled icorrenctly, can you sltil udsternand me?” Korean does this too because it has enough characters to make words with distinct and different shapes. However, because the visual cues are not distinct as Kanji, spaces needed to be added to remove ambiguities. (This presents another problem of when and where to set spaces.)

With Kanji, we don’t have to worry about spaces and much of the problem of homophones is mostly resolved. Without Kanji, even if spaces were to be added, the ambiguities and lack of visual cues would make Japanese text much more difficult to read.

How To Write In Japanese – A Beginner’s Guide

by Olly Richards

Do you want to learn how to write in Japanese, but feel confused or intimidated by the script?

This post will break it all down for you, in a step-by-step guide to reading and writing skills this beautiful language.

I remember when I first started learning Japanese and how daunting the writing system seemed. I even wondered whether I could get away without learning the script altogether and just sticking with romaji (writing Japanese with the roman letters).

I’m glad I didn’t.

If you’re serious about learning Japanese, you have to get to grips with the script sooner or later. If you don’t, you won’t be able to read or write anything useful, and that’s no way to learn a language.

The good news is that it isn’t as hard as you think. And I’ve teamed up with my friend Luca Toma (who’s also a Japanese coach) to bring you this comprehensive guide to reading and writing Japanese.

By the way, if you want to learn Japanese fast and have fun while doing it, my top recommendation is Japanese Uncovered which teaches you through StoryLearning®.

With Japanese Uncovered you’ll use my unique StoryLearning® method to learn Japanese naturally through story… not rules. It’s as fun as it is effective.

If you’re ready to get started, click here for a 7-day FREE trial.

Don’t have time to read this now? Click here to download a free PDF of the article.

If you have a friend who’s learning Japanese, you might like to share it with them. Now, let’s get stuck in…

One Language, Two Systems, Three Scripts

If you are a complete beginner, Japanese writing may appear just like Chinese.

But if you look at it more carefully you’ll notice that it doesn’t just contain complex Chinese characters… there are lots of simpler ones too.

それでも、 日本人 の 食生活 も 急速 に 変化 してきています 。 ハンバーグ や カレーライス は 子供に人気 がありますし 、都会 では 、 イタリア 料理、東南 アジア 料理、多国籍料理 などを 出 す エスニック 料理店 がどんどん 増 えています 。

(Source: “Japan: Then and Now”, 2001, p. 62-63)

As you can see from this sample, within one Japanese text there are actually three different scripts intertwined. We’ve colour coded them to help you tell them apart.

(What’s really interesting is the different types of words – parts of speech – represented by each colour – it tells you a lot about what you use each of the three scripts for.)

Can you see the contrast between complex characters (orange) and simpler ones (blue and green)?

The complex characters are called kanji (漢字 lit. Chinese characters) and were borrowed from Chinese. They are what’s called a ‘logographic system’ in which each symbol corresponds to a block of meaning (食 ‘to eat’, 南 ‘south’, 国 ‘country’).

Each kanji also has its own pronunciation, which has to be learnt – you can’t “read” an unknown kanji like you could an unknown word in English.

Luckily, the other two sets of characters are simpler!

Those in blue above are called hiragana and those in green are called katakana. Katakana and hiragana are both examples of ‘syllabic systems’, and unlike the kanji, each character corresponds to single sound. For example, そ= so, れ= re; イ= i, タ = ta.

Hiragana and katakana are a godsend for Japanese learners because the pronunciation isn’t a problem. If you see it, you can say it!

So, at this point, you’re probably wondering:

“What’s the point of using three different types of script? How could that have come about?”

In fact, all these scripts have a very specific role to play in a piece of Japanese writing, and you’ll find that they all work together in harmony in representing the Japanese language in a written form.

So let’s check them out in more detail.

The ‘Kana’ – One Symbol, One Sound

Both hiragana and katakana have a fixed number of symbols: 46 characters in each, to be precise.

Each of these corresponds to a combination of the 5 Japanese vowels (a, i, u, e o) and the 9 consonants (k, s, t, n, h, m, y, r, w).

Hiragana (the blue characters in our sample text) are recognizable for their roundish shape and you’ll find them being used for three functions in Japanese writing:

1. Particles (used to indicate the grammatical function of a word)

は wa topic marker

が ga subject marker

を wo direct object marker

2. To change the meaning of verbs, adverbs or adjectives, which generally have a root written in kanji. (“Inflectional endings”)

急速 に kyuusoku ni rapid ly

増 えています fu ete imasu are increas ing

3. Native Japanese words not covered by the other two scripts

それでも soredemo nevertheless

どんどん dondon more and more

Katakana (the green characters in our sample text) are recognisable for their straight lines and sharp corners. They are generally reserved for:

1. Loanwords from other languages. See what you can spot!

ハンバーグ hanbaagu hamburger

カレーライス karee raisu curry rice

エスニック esunikku ethnic

2. Transcribing foreign names

イタリア itaria Italy

They are also used for emphasis (the equivalent of italics or underlining in English), and for scientific terms (plants, animals, minerals, etc.).

So where did hiragana and katakana come from?

In fact, they were both derived from kanji which had a particular pronunciation; Hiragana took from the Chinese cursive script (安 an →あ a), whereas katakana developed from single components of the regular Chinese script (阿 a →ア a ).

So that covers the origins the two kana scripts in Japanese, and how we use them.

Now let’s get on to the fun stuff… kanji!

The Kanji – One Symbol, One Meaning

Kanji – the most formidable hurdle for learners of Japanese!

We said earlier that kanji is a logographic system, in which each symbol corresponds to a “block of meaning”.

“Block of meaning” is the best phrase, because one kanji is not necessarily a “word” on its own.

You might have to combine one kanji with another in order to make an actual word, and also to express more complex concepts:

生 + 活 = 生活 lifestyle

食 + 生活 = 食生活 eating habits

If that sounds complicated, remember that you see the same principle in other languages.

Think about the word ‘telephone’ in English – you can break it down into two main components derived from Greek:

‘tele’ (far) + ‘phone’ (sound) = telephone

Neither of them are words in their own right.

So there are lots and lots of kanji, but in order to make more sense of them we can start by categorising them.

There are several categories of kanji, starting with the ‘pictographs’ (象形文字shōkei moji), which look like the objects they represent:

In fact, there aren’t too many of these pictographs.

Around 90% of the kanji in fact come from six other categories, in which several basic elements (called ‘radicals’) are combined to form new concepts.

人 (‘man’ as a radical) + 木 (‘tree’) = 休 (‘to rest’)

These are known as 形声文字 keisei moji or ‘radical-phonetic compounds’.

You can think of these characters as being made up of two parts:

So that’s the story behind the kanji, but what are they used for in Japanese writing?

Typically, they are used to represent concrete concepts.

When you look at a piece of Japanese writing, you’ll see kanji being used for nouns, and in the stem of verbs, adjectives and adverbs.

Here are some of them from our sample text at the start of the article:

日本人 Japanese people

多国籍料理 multinational cuisine

東南 Southeast

Now, here’s the big question!

Once you’ve learnt to read or write a kanji, how do you pronounce it?

If you took the character from the original Chinese, it would usually only have one pronunciation.

However, by the time these characters leave China and reach Japan, they usually have two or sometimes even more pronunciations.

How or why does this happen?

Let’s look at an example.

To say ‘mountain’, the Chinese use the pictograph 山 which depicts a mountain with three peaks. The pronunciation of this character in Chinese is shān (in the first tone).

Now, in Japanese the word for ‘mountain’ is ‘yama’.

So in this case, the Japanese decided to borrow the character山from Chinese, but to pronounce it differently: yama.

However, this isn’t the end of the story!

The Japanese did decide to borrow the pronunciation from the original Chinese, but only to use it when that character is used in compound words.

So, in this case, when the character 山 is part of a compound word, it is pronounced as san/zan – clearly an approximation to the original Chinese pronunciation.

Here’s the kanji on its own:

山は… Yama wa… The mountain….

And here’s the kanji when it appears in compound words:

火山は… Ka zan wa The volcano…

富士山は… Fuji san wa… Mount Fuji….

To recap, every kanji has at least two pronunciations.

The first one (the so-called訓読み kun’yomi or ‘meaning reading’) has an original Japanese pronunciation, and is used with one kanji on it’s own.

The second one (called音読み on’yomi or ‘sound-based reading’) is used in compound words, and comes from the original Chinese.

Makes sense, right? 😉

In Japan, there’s an official number of kanji that are classified for “daily use” (常用漢字joyō kanji) by the Japanese Ministry of Education – currently 2,136.

(Although remember that the number of actual words that you can form using these characters is much higher.)

So now… if you wanted to actually learn all these kanji, how should you go about it?

To answer this question, Luca’s going to give us an insight into how he did it.

How I Learnt Kanji

I started to learn kanji more than 10 years ago at a time when you couldn’t find all the great resources that are available nowadays. I only had paper kanji dictionary and simple lists from my textbook.

What I did have, however, was the memory of a fantastic teacher.

I studied Chinese for two years in college, and this teacher taught us characters in two helpful ways:

Once I’d learnt to recognise the 214 radicals which make up all characters – the building blocks of Chinese characters – it was then much easier to go on and learn the characters and the words themselves.

It’s back to the earlier analogy of dividing the word ‘telephone’ into tele and phone.

But here’s the thing – knowing the characters alone isn’t enough. There are too many, and they’re all very similar to one another.

If you want to get really good at the language, and really know how to read and how to write in Japanese, you need a higher-order strategy.

The number one strategy that I used to reach a near-native ability in reading and writing in Japanese was to learn the kanji within the context of dialogues or other texts.

I never studied them as individual characters or words.

Now, I could give you a few dozen ninja tricks for how to learn Japanese kanji. But the one secret that blows everything else out of the water and guarantees real success in the long-term, is extensive reading and massive exposure.

This is the foundation of the StoryLearning® method, where you immerse yourself in language through story.

In the meantime, there are a lot of resources both online and offline to learn kanji, each of which is based on a particular method or approach (from flashcards to mnemonic and so on).

The decision of which approach to use can be made easier by understanding the way you learn best.

Do you have a photographic memory or prefer working with images? Do you prefer to listen to audio? Or perhaps you prefer to write things by hands?

You can and should try more than one method, in order to figure out which works best for you.

( Note : You should get a copy of this excellent guide by John Fotheringham, which has all the resources you’ll ever need to learn kanji)

Summary Of How To Write In Japanese

So you’ve made it to the end!

See – I told you it wasn’t that bad! Let’s recap what we’ve covered.

Ordinary written Japanese employs a mixture of three scripts:

In special cases, such as children’s books or simplified materials for language learners, you might find everything written using only hiragana or katakana.

But apart from those materials, everything in Japanese is written by employing the three scripts together. And it’s the kanji which represent the cultural and linguistic challenge in the Japanese language.

If you want to become proficient in Japanese you have to learn all three!

Although it seems like a daunting task, remember that there are many people before you who have found themselves right at the beginning of their journey in learning Japanese.

And every journey begins with a single step.

So what are you waiting for?

The best place to start is to enrol in Japanese Uncovered. The course includes a series of lessons that teach you hiragana, katakana and kanji. It also includes an exciting Japanese story which comes in different formats (romaji, hiragana, kana and kanji) so you can practice reading Japanese, no matter what level you’re at right now.

If you’re ready to get started, click here for a 7-day FREE trial.

It’s been a pleasure for me to work on this article with Luca Toma, and I’ve learnt a lot in the process.

Now he didn’t ask me to write this, but if you’re serious about learning Japanese, you should consider hiring Luca as a coach. The reasons are many, and you can find out more on his website: JapaneseCoaching.it

Do you know anyone learning Japanese? Why not send them this article, or click here to send a tweet.

Primary Sidebar

Japanese Tips by Email?

Get my best fluency-boosting, grammar-busting Japanese tips by email.