How to write your college essay

How to write your college essay

This blog has over 100 posts.

Know what that means?

It means I’ve spent a lot of time thinking and writing about college essays.

A lot of other people have too.

So I thought I’d ask my brother, who helps me with my website, to reach out to some of my favorite college admissions experts—some current and former admissions officers—and ask one simple question:

WHAT’S your favorite piece of advice about writing a college essay?

Below are the results.

College Essay Tips from University Admission Administrators

1. know that the best ideas for your essay—the perfect opener, a great twist, a brilliant insight—often come when you least expect them.

That’s why it’s a good practice to keep a reliable collection system with you at all times as you’re preparing to write your essay. It could be your phone. It could be index cards. It could be a Moleskine notebook (if you really want to do it with panache). Just don’t store it in your own brain thinking that you’ll remember it later. Your mind may be a magnificently wonderful idea-making machine, but it’s a lousy filing cabinet. Store those ideas in one place outside your brain so that when inspiration hits you in the bathroom, in the car, on a hike—wherever—you’ll have a place to capture it and come back to it later when you need it.

This college essay tip is by Ken Anselment, Marquette University graduate and Vice President for Enrollment & Communication at Lawrence University.

2. Do not feel pressure to share every detail of challenging experiences, but also do not feel that you need to have a happy ending or solution.

Your writing should provide a context within which the reader learns about who you are and what has brought you to this stage in your life. Try to tie your account into how this has made you develop as a person, friend, family member or leader (or any role in your life that is important to you). You may also want to make a connection to how this has inspired some part of your educational journey or your future aspirations.

This college essay tip is by Jaclyn Robins, Assistant Director of admissions at the University of Southern California. The tip below is paraphrased from a post on the USC admissions blog.

3. Read it aloud.

There is something magical about reading out loud. As adults we don’t do this enough. In reading aloud to kids, colleagues, or friends we hear things differently, and find room for improvement when the writing is flat. So start by voice recording your essay.

This college essay tip is by Rick Clark, director of undergraduate admissions at Georgia Tech. The tip below is paraphrased from a post on the Georgia Tech Admission blog.

4. We want to learn about growth.

Some students spend a lot of time summarizing plot or describing their work and the «in what way» part of the essay winds up being one sentence. The part that is about you is the most important part. If you feel you need to include a description, make it one or two lines. Remember that admission offices have Google, too, so if we feel we need to hear the song or see the work of art, we’ll look it up. The majority of the essay should be about your response and reaction to the work. How did it affect or change you?

This college essay tip is by Dean J, admissions officer and blogger from University of Virginia. The tip below is paraphrased from a post on the University of Virginia Admission blog.

5. Be specific.

Consider these two hypothetical introductory paragraphs for a master’s program in library science.

“I am honored to apply for the Master of Library Science program at the University of Okoboji because as long as I can remember I have had a love affair with books. Since I was eleven I have known I wanted to be a librarian.”

“When I was eleven, my great-aunt Gretchen passed away and left me something that changed my life: a library of about five thousand books. Some of my best days were spent arranging and reading her books. Since then, I have wanted to be a librarian.”

Each graf was 45 words long and contained substantively the same information (applicant has wanted to be a librarian since she was a young girl). But they are extraordinarily different essays, most strikingly because the former is generic where the latter is specific. It was a real thing, which happened to a real person, told simply. There is nothing better than that.

This college essay tip is by Chris Peterson, Assistant Director at MIT Admissions. The tip below is paraphrased from the post “How To Write A College Essay” on the MIT blog.

6. Tell a good story.

Most people prefer reading a good story over anything else. So. tell a great story in your essay. Worry less about providing as many details about you as possible and more about captivating the reader’s attention inside of a great narrative. I read a great essay this year where an applicant walked me through the steps of meditation and how your body responds to it. Loved it. (Yes, I’ll admit I’m a predisposed meditation fan.)

This college essay tip is by Jeff Schiffman, Director of Admissions at Tulane University and health and fitness nut.

7. Write like you speak.

Here’s my favorite trick when I’ve got writer’s block: turn on the recording device on my phone, and just start talking. I actually use voice memos in my car when I have a really profound thought (or a to do list I need to record), so find your happy place and start recording. Maybe inspiration always seems to strike when you’re walking your dog, or on the bus to school. Make notes where and when you can so that you can capture those organic thoughts for later. This also means you should use words and phrases that you would actually use in everyday conversation. If you are someone who uses the word indubitably all the time, then by all means, go for it. But if not, then maybe you should steer clear. The most meaningful essays are those where I feel like the student is sitting next to me, just talking to me.

This college essay tip is by Kim Struglinski, admissions counselor from Vanderbilt University. The tip below is paraphrased from the excellent post “Tips for Writing Your College Essay” on the Vanderbilt blog.

8. Verb you, Dude!

Verbs jump, dance, fall, fail us. Nouns ground us, name me, define you. “We are the limits of our language.” Love your words, feed them, let them grow. Teach them well and they will teach you too. Let them play, sing, or sob outside of yourself. Give them as a gift to others. Try the imperative, think about your future tense, when you would have looked back to the imperfect that defines us and awaits us. Define, Describe, Dare. Have fun.

This college essay tip is by Parke Muth, former associate dean of Admissions at the University of Virginia (28 years in the office) and member of the Jefferson Scholars selection committee.

9. Keep the story focused on a discrete moment in time.

By zeroing in on one particular aspect of what is, invariably, a long story, you may be better able to extract meaning from the story. So instead of talking generally about playing percussion in the orchestra, hone in on a huge cymbal crash marking the climax of the piece. Or instead of trying to condense that two-week backpacking trip into a couple of paragraphs, tell your reader about waking up in a cold tent with a skiff of snow on it. The specificity of the story not only helps focus the reader’s attention, but also opens the door to deeper reflection on what the story means to you.

This college essay tip is by Mark Montgomery, former Associate Dean at the University of Denver, admissions counselor for Fort Lewis College, founder of Great College Advice, and professor of international affairs at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology Kansas.

10. Start preparing now.

Yes, I know it’s still summer break. However, the essay is already posted on our website here and isn’t going to change before the application opens on September 1. Take a look, and start to formulate your plan. Brainstorm what you are going to tell us — focus on why you are interested in the major you chose. If you are choosing the Division of General Studies, tells us about your passions, your career goals, or the different paths you are interested in exploring.

This college essay tip is by Hanah Teske, admissions counselor at the University of Illinois. This tip was paraphrased form Hanah’s blog post on the University of Illinois blog.

11. Imagine how the person reading your essay will feel.

No one’s idea of a good time is writing a college essay, I know. But if sitting down to write your essay feels like a chore, and you’re bored by what you’re saying, you can imagine how the person reading your essay will feel. On the other hand, if you’re writing about something you love, something that excites you, something that you’ve thought deeply about, chances are I’m going to set down your application feeling excited, too—and feeling like I’ve gotten to know you.

This college essay tip is by Abigail McFee, Admissions Counselor for Tufts University and Tufts ‘17 graduate.

College Essay Tips from College Admissions Experts

12. Think outside the text box!

Put a little pizazz in your essays by using different fonts, adding color, including foreign characters or by embedding media—links, pictures or illustrations. And how does this happen? Look for opportunities to upload essays onto applications as PDFs. It’s not always possible, but when it is, you will not only have complete control over the ‘look’ of your essay but you will also potentially enrich the content of your work.

This college essay tip is by Nancy Griesemer, University of Pennsylvania and Harvard University graduate and founder of College Explorations who has decades of experiencing counseling high schoolers on getting into college.

13. Write like a journalist.

«Don’t bury the lede!» The first few sentences must capture the reader’s attention, provide a gist of the story, and give a sense of where the essay is heading. Think about any article you’ve read—how do you decide to read it? You read the first few sentences and then decide. The same goes for college essays. A strong lede (journalist parlance for «lead») will place your reader in the «accept» mindset from the beginning of the essay. A weak lede will have your reader thinking «reject»—a mindset from which it’s nearly impossible to recover.

This college essay tip is by Brad Schiller, MIT graduate and CEO of Prompt, which provides individualized feedback on thousands of students’ essays each year.

14. I promote an approach called “into, through, and beyond.”

(This approach) pushes kids to use examples to push their amazing qualities, provide some context, and end with hopes and dreams. Colleges are seeking students who will thrive on their campuses, contribute in numerous ways, especially “bridge” building, and develop into citizens who make their worlds and our worlds a better place. So application essays are a unique way for applicants to share, reflect, and connect their values and goals with colleges. Admissions officers want students to share their power, their leadership, their initiative, their grit, their kindness—all through relatively recent stories. I ask students: “Can the admissions officers picture you and help advocate for you by reading your essays?” Often kids don’t see their power, and we can help them by realizing what they offer colleges through their activities and life experiences. Ultimately I tell them, “Give the colleges specific reasons to accept you—and yes you will have to ‘brag.’ But aren’t you worth it? Use your essays to empower your chances of acceptance, merit money, and scholarships.”

This college essay tip is by Dr. Rebecca Joseph, professor at California State University and founder of All College Application Essays, develops tools for making the college essay process faster and easier.

15. Get personal.

To me, personal stuff is the information you usually keep to yourself, or your closest friends and family. So it can be challenging, even painful, to dig up and share. Try anyway. When you open up about your feelings—especially in response to a low point—you are more likely to connect with your reader(s). Why? Because we’ve all been there. So don’t overlook those moments or experiences that were awkward, uncomfortable or even embarrassing. Weirdly, including painful memories (and what you learned from them!) usually helps a personal statement meet the goals of a college application essay—you come across as humble, accessible, likable (this is HUGE!), and mature. Chances are, you also shared a mini-story that was interesting, entertaining and memorable.

This college essay tip is by Janine Robinson, journalist, credentialed high school English teacher, and founder of Essay Hell, has spent the last decade coaching college-bound students on their college application essays.

16. Just make sure that the story you’re telling is uniquely YOURS.

I believe everyone has a story worth telling. Don’t feel like you have to have had a huge, life-changing, drama-filled experience. Sometimes the seemingly smallest moments lead us to the biggest breakthroughs.

This college essay tip is by Maggie Schuh, a member of the Testive Parent Success team and a high school English teacher in St. Louis.

17. Keep it simple!

No one is expecting you to solve the issue of world peace with your essay. Oftentimes, we find students getting hung up with “big ideas”. Remember, this essay is about YOU. What makes you different from the thousands of other applicants and their essays? Be specific. Use vivid imagery. If you’re having trouble, start small and go from there. P. S. make sure the first sentence of your essay is the most interesting one.

This college essay tip is by Myles Hunter, CEO of TutorMe, an online education platform that provides on-demand tutoring and online courses for thousands of students.

18. Honor your inspiration.

My parents would have much preferred that I write about sports or youth group, and I probably could have said something interesting about those, but I insisted on writing about a particular fish in the pet store I worked at—one that took much longer than the others to succumb when the whole tank system in the store became diseased. It was a macabre little composition, but it was about exactly what was on my mind at the time I was writing it. I think it gave whoever read it a pretty good view of my 17 year-old self. I’ll never know if I got in because of that weird essay or in spite of it, but it remains a point of pride that I did it my way.

This college essay tip is by Mike McClenathan, founder of PwnTestPrep, which has a funny name but serious resources for helping high school students excel on the standardized tests.

19. Revise often and early.

Your admissions essay should go through several stages of revision. And by revisions, we don’t mean quick proofreads. Ask your parents, teachers, high school counselors or friends for their eyes and edits. It should be people who know you best and want you to succeed. Take their constructive criticism in the spirit for which they intend—your benefit.

This college essay tip is by Dhivya Arumugham, Kaplan Test Prep’s director of SAT and ACT programs.

20. Write about things you care about.

The most obvious things make great topics. What do I mean? Colleges want to learn about who you are, what you value and how you will contribute to their community. I had two students write about their vehicles—one wrote about the experience of purchasing their used truck and one wrote about how her car is an extension of who she is. We learned about their responsibility, creative thinking, teamwork and resilience in a fun and entertaining way.

This college essay tip is by Mira “Coach Mira” Simon, Independent Educational Consultant and professionally trained coach from the Institute of Professional Excellence in Coaching (iPEC), who combines her expertise to help high school students find their pathway to college.

21. Don’t tell them a story you think they want, tell them what YOU want.

Of course you want it to be a good read and stay on topic, but this is about showing admissions who you are. You don’t want to get caught up in thinking too much about what they are expecting. Focus your thoughts on yourself and what you want to share.

This college essay tip is by Ashley McNaughton, Bucknell University graduate and founder of ACM College Consulting, consults on applicants internationally and volunteers with high achieving, low income students through ScholarMatch.

22. Be yourself.

A sneaky thing can happen as you set about writing your essay: you may find yourself guessing what a college admissions committee is looking for and writing to meet that made up criteria rather than standing firm in who you are and sharing your truest self. While you want to share your thoughts in the best possible light (edit please!), avoid the temptation minimize the things that make you who you are. Show your depth. Be honest about what matters to you. Be thoughtful about the experiences you’ve had that have shaped who you’ve become. Be your brilliant self. And trust that your perfect-fit college will see you for who truly you are and say «Yes! This is exactly who we’ve been looking for.”

This college essay tip is by Lauren Gaggioli, NYU graduate, host of The College Checklist podcast, and founder of Higher Scores Test Prep provides affordable test prep help to college applicants.

23. Parents should NEVER write a student’s essay.

Admission officers can spot parent content immediately. The quickest way for a student to be denied admission is to allow a parent to write or edit with their own words. Parents can advise, encourage, and offer a second set of eyes, but they should never add their own words to a student’s essay.

This college essay tip is by Suzanne Shaffer is a college prep expert, blogger, and author who manages the website Parenting for College.

24. Don’t just write about your resume, recommendations, and high school transcripts.

Admissions officers want to know about you, your personality and emotions. For example, let them know what hobbies, interests, or passions you have. Do you excel in athletics or art? Let them know why you excel in those areas. It’s so important to just be yourself and write in a manner that lets your personality shine through.

This college essay tip is by College Basic Team. College Basics offers free, comprehensive resources for both parents and students to help them navigate through the college application process and has been featured on some of the web’s top educational resource websites as well as linked to from well over 100+ different colleges, schools, and universities.

25. Find a way to showcase yourself without bragging.

Being confident is key, but you don’t want to come across as boasting. Next, let them know how college will help you achieve your long-term goals. Help them connect the dots and let them know you are there for a reason. Finally (here’s an extra pro tip), learn how to answer common college interview questions within your essay. This will not only help you stand out from other applicants, but it will also prepare you for the college interview ahead of time as well.

26. Be real.

As a former college admissions officer, I read thousands of essays—good and bad. The essays that made the best impressions on me were the essays that were real. The students did not use fluff, big words, or try to write an essay they thought admission decisions makers wanted to read. The essays that impressed me the most were not academic essays, but personal statements that allowed me to get to know the reader. I was always more likely to admit or advocate for a student who was real and allowed me to get to know them in their essay.

This college essay tip is by Jessica Velasco, former director of admissions at Northwest University and founder of JLV College Counseling.

27. Don’t begin with “throat clearing.”

“As I consider all the challenges I have faced in my life, I find myself most affected by the experiences I have had working at a high-end coffee shop, where I learned some important lessons about myself.”

I know her name is Amy but when she orders the vanilla macchiato she instructs me to write “Anastasia,” on the cardboard cup, deliberately pronouncing each letter as if it weren’t the hundredth time I’ve heard it.

Skip the moral-of-the-story conclusions, too. Don’t tell the admission folks, “Now I know I can reach whatever goals I set.” If your essay says what it’s supposed to, they’ll figure it out.

Warm-up strategy: Read the first two sentences and last two sentences in a few of your favorite novels. Did you spot any throat-clearing or moral-of-the-story endings? Probably not!

This college essay tip is by Sally Rubenstone, senior contributor to College Confidential, author of the “Ask the Dean” column, co-author of several books on college admissions, 15-year Smith College admission counselor, and teacher.

28. Don’t read the Common Application prompts.

If you already have, erase them from memory and write the story you want colleges to hear. The truth is, admission reviewers rarely know—or care—which prompt you are responding to. They are curious to discover what you choose to show them about who you are, what you value, and why. Even the most fluid writers are often stifled by fitting their narrative neatly into a category and the essay quickly loses authentic voice. Write freely and choose a prompt later. Spoiler alert. one prompt is «Share an essay on any topic of your choice. It can be one you’ve already written, one that responds to a different prompt, or one of your own design. » So have at it.

This college essay tip is by Brennan Barnard, director of college counseling at the Derryfield School in Manchester, N.H. and contributor to the NYT, HuffPost, and Forbes on intentionally approaching college admissions.

29. Proofread, proofread, proofread.

Nothing’s perfect, of course, but the grammar, spelling, and punctuation in your admission essay should be as close to perfect as possible. After you’re done writing, read your essay, re-read it a little later, and have someone else read it too, like a teacher or friend—they may find typos that your eyes were just too tired to see.

Colleges are looking for students who can express their thoughts clearly and accurately, and polishing your essay shows that you care about producing high-quality, college-level work. Plus, multiple errors could lower your chances of admission. So take the extra time and edit!

This college essay tip is by Claire Carter, University of Maine graduate and editor of CollegeXpress, one of the internet’s largest college and scholarship search engines.

30. Take the pressure off and try free-writing to limber up.

If you are having trouble coming up with what it is you want to convey or finding the perfect story to convey who you are, use prompts such as:

Share one thing that you wish people knew about you.

My biggest dream is ___________.

What have you enjoyed about high school?

Use three adjectives to describe yourself:____________, ___________, ________.

I suggest handwriting (versus typing on a keyboard) for 20 minutes. Don’t worry about making it perfect, and don’t worry about what you are going to write about. Think about getting yourself into a meditative state for 20 minutes and just write from the heart.

To get myself in a meditative state, I spend 60 seconds (set an alarm) drawing a spiral. Never let the pen come off the page, and just keep drawing around and around until the alarm goes off. Then, start writing.

It might feel you didn’t write anything worthwhile, but my experience is that there is usually a diamond in the rough in there. perhaps more than one.

Do this exercise for 3-4 days straight, then read out loud what you have written to a trusted source (a parent? teacher? valued friend?).

Don’t expect a masterpiece from this exercise (though stranger things have happened).

The goal is to discover the kernel of any idea that can blossom into your college essay—a story that will convey your message, or clarity about what message you want to convey.

Here is a picture of the spiral, in case you have trouble visualizing:

This college essay tip is by Debbie Stier, publisher, author of the same-title book The Perfect Score Project, featured on NBC’s Today Show, Bloomberg TV, CBS This Morning; in The New Yorker, The New York Post, USA Today, and more.

31. Show your emotions.

Adding feelings to your essays can be much more powerful than just listing your achievements. It allows reviewers to connect with you and understand your personality and what drives you. In particular, be open to showing vulnerability. Nobody expects you to be perfect and acknowledging times in which you have felt nervous or scared shows maturity and self-awareness.

This college essay tip is by Charles Maynard, Oxford and Stanford University Graduate and founder of Going Merry, which is a one-stop shop for applying to college scholarships

32. Be genuine and authentic. Make sure at least one “qualified” person edits your essay.

Your essay should be a true representation of who you are as a person—admissions officers want to read essays that are meaningful, thoughtful, and consistent with the rest of the application. Essays that come from the heart are the easiest to write and the best written. Have a teacher or counselor, not just your smartest friend, review and edit your essays. Don’t let mistakes and grammatical errors detract from your application.

This college essay tip is by Jonathan April, University of Chicago graduate, general manager of College Greenlight, which offers free tools to low-income and first-generation students developing their college lists.

COLLEGE ESSAY GUY’S COLLEGE ESSAY TIPS

The following essay, written by a former student, is so good that it illustrates at least five essential tips of good essay writing. It’s also one way to turn the objects exercise into an essay. Note how the writer incorporates a wide range of details and images through one particular lens: a scrapbook.

Prompt: Describe the world you come from — for example, your family, community or school — and tell us how your world has shaped your dreams and aspirations.

The Scrapbook Essay

I look at the ticking, white clock: it’s eleven at night, my primetime. I clear the carpet of the Sony camera charger, the faded Levi’s, and last week’s Statistics homework. Having prepared my work space, I pull out the big, blue box and select two 12 by 12 crème sheets of paper. The layouts of the pages are already imprinted in my mind, so I simply draw them on scratch paper. Now I can really begin.

Cutting the first photograph, I make sure to leave a quarter inch border. I then paste it onto a polka-dotted green paper with a glue stick. For a sophisticated touch, I use needle and thread to sew the papers together. Loads of snipping and pasting later, the clock reads three in the morning. I look down at the final product, a full spread of photographs and cut-out shapes. As usual, I feel an overwhelming sense of pride as I brush my fingers over the crisp papers and the glossy photographs. For me, the act of taking pieces of my life and putting them together on a page is my way of organizing remnants of my past to make something whole and complete.

This particular project is the most valuable scrapbook I have ever made: the scrapbook of my life.

In the center of the first page are the words MY WORLD in periwinkle letters. The entire left side I have dedicated to the people in my life. All four of my Korean grandparents sit in the top corner; they are side by side on a sofa for my first birthday –my ddol. Underneath them are my seven cousins from my mom’s side. They freeze, trying not to let go of their overwhelming laughter while they play “red light, green light” at O’ Melveney Park, three miles up the hill behind my house. Meanwhile, my Texas cousins watch Daniel, the youngest, throw autumn leaves into the air that someone had spent hours raking up. To the right, my school peers and I miserably pose for our history teacher who could not resist taking a picture when he saw our droopy faces the morning of our first AP exam. The biggest photograph, of course, is that of my family, huddled in front of the fireplace while drinking my brother’s hot cocoa and listening to the pitter patter of rain outside our window.

I move over to the right side of the page. At the top, I have neatly sewn on three items. The first is a page of a Cambodian Bible that was given to each of the soldiers at a military base where I taught English. Beneath it is the picture of my Guatemalan girls and me sitting on the dirt ground while we devour arroz con pollo, red sauce slobbered all over our lips. I reread the third item, a short note that a student at a rural elementary school in Korea had struggled to write in her broken English. I lightly touch the little chain with a dangling letter E included with the note. Moving to the lower portion of the page, I see the photo of the shelf with all my ceramic projects glazed in vibrant hues. With great pride, I have added a clipping of my page from the Mirror, our school newspaper, next to the ticket stubs for Wicked from my date with Dad. I make sure to include a photo of my first scrapbook page of the visit to Hearst Castle in fifth grade.

After proudly looking at each detail, I turn to the next page, which I’ve labeled: AND BEYOND. Unlike the previous one, this page is not cluttered or crowded. There is my college diploma with the major listed as International Relations; however, the name of the school is obscure. A miniature map covers nearly half of the paper with numerous red stickers pinpointing locations all over the world, but I cannot recognize the countries’ names. The remainder of the page is a series of frames and borders with simple captions underneath. Without the photographs, the descriptions are cryptic.

For now, that second page is incomplete because I have no precise itinerary for my future. The red flags on the map represent the places I will travel to, possibly to teach English like I did in Cambodia or to do charity work with children like I did in Guatemala. As for the empty frames, I hope to fill them with the people I will meet: a family of my own and the families I desire to help, through a career I have yet to decide. Until I am able to do all that, I can prepare. I am in the process of making the layout and gathering the materials so that I can start piecing together the next part, the next page of my life’s scrapbook.

Analysis of The Scrapbook Essay

(or)

Five Things We Can Steal from This Essay

A great thinker once said “Good artists borrow; great artists steal.” I’m not even going to tell you who said it; I’m stealing it.

#33 Use objects and images instead of adjectives

Check out the opening paragraph of the Scrapbook essay again. It reads like the opening to a movie. Can you visualize what’s happening? That’s good. Take a look at the particular objects the writer chose:

I look at the ticking, white clock: it’s eleven at night, my primetime. I clear the carpet of the Sony camera charger, the faded Levi’s, and last week’s Statistics homework. Having prepared my work space, I pull out the big, blue box and select two 12 by 12 crème sheets of paper. The layouts of the pages are already imprinted in my mind, so I simply draw them on scratch paper. Now I can really begin.

Let’s zoom in on the “faded Levi’s.” What does «faded» suggest? (She keeps clothes for a long time; she likes to be comfortable.) What does «Levi’s» suggest? (She’s casual; she’s not fussy.) And why does she point out that they’re on the floor? (She’s not obsessed with neatness.)

Every. Word. Counts.

Now re-read the sentence about her family:

The biggest photograph, of course, is that of my family, huddled in front of the fireplace while drinking my brother’s hot cocoa and listening to the pitter patter of rain outside our window.

What do these details tell us?

The biggest photograph: Why “biggest»? (Family is really important to her.)

Fireplace: What does a fireplace connote? (Warmth, closeness.)

My brother’s hot cocoa: Why hot cocoa? (Again, warmth.) And why “my brother’s” hot cocoa? Why not “mom’s lemonade”? How is the fact that her brother made it change the image? (It implies that her brother is engaged in the family activity.) Do you think she likes her brother? Would your brother make hot cocoa for you? And finally:

Listening to rain: Why not watching TV? What does it tell you about this family that they sit and listen to rain together?

Notice how each of these objects are objective correlatives for the writer’s family. Taken together, they create an essence image.

Quick: What essence image describes your family? Even if you have a non-traditional family–in fact, especially if you have a non-traditional family!–what image or objects represents your relationship?

Based on the image the writer uses, how would you describe her relationship with her family? Close? Warm? Intimate? Loving? Quiet? But think how much worse her essay would have been if she’d written: “I have a close, warm, intimate, loving, quiet relationship with my family.”

Instead, she describes an image of her family «huddled in front of the fireplace while drinking my brother’s hot cocoa and listening to the pitter patter of rain outside our window.” Three objects—fireplace, brother’s hot cocoa, sound of rain—and we get the whole picture of their relationship. We know all we need to know.

There’s another lesson here:

#34 Engage the reader’s imagination using all five senses

This writer did. Did you notice?

Brother’s hot cocoa (taste, smell)

Pitter patter of rain (sound)

Biggest photograph (sight)

And there’s something else she did that’s really smart. Did you notice how clearly she set up the idea of the scrapbook at the beginning of the essay? Look at the last sentence of the second paragraph (bolded below):

Cutting the first photograph, I make sure to leave a quarter inch border. I then paste it onto a polka-dotted green paper with a glue stick. For a sophisticated touch, I use needle and thread to sew the papers together. Loads of snipping and pasting later, the clock reads three in the morning. I look down at the final product, a full spread of photographs and cut-out shapes. As usual, I feel an overwhelming sense of pride as I brush my fingers over the crisp papers and the glossy photographs. For me, the act of taking pieces of my life and putting them together on a page is my way of organizing remnants of my past to make something whole and complete.

The sentence in bold above is essentially her thesis. It explains the framework for the whole essay. She follows this sentence with:

This particular project is the most valuable scrapbook I have ever made: the scrapbook of my life.

Boom. Super clear. And we’re set-up for the rest of the essay. So here’s the third thing we can learn:

#35 The set-up should be super clear

Even a personal statement can have a thesis. It’s important to remember that, though your ending can be somewhat ambiguous—something we’ll discuss more later—your set-up should give the reader a clear sense of where we’re headed. It doesn’t have to be obvious, and you can delay the thesis for a paragraph or two (as this writer does), but at some point in the first 100 words or so, we need to know we’re in good hands. We need to trust that this is going to be worth our time.

#36 Show THEN Tell

Has your English teacher ever told you “Show, don’t tell?” That’s good advice, but for a college essay I believe it’s actually better to show THEN tell.

Why? Two reasons:

1.) Showing before telling gives your reader a chance to interpret the meaning of your images before you do. Why is this good? It provides a little suspense. Also, it engages the reader’s imagination. Take another look at the images in the second to last paragraph: my college diploma. a miniature map with numerous red stickers pinpointing locations all over the world. frames and borders without photographs. (Note that it’s all «show.»)

As we read, we wonder: what do all these objects mean? We have an idea, but we’re not certain. Then she TELLS us:

That second page is incomplete because I have no precise itinerary for my future. The red flags on the map represent the places I will travel to, possibly to teach English like I did in Cambodia or to do charity work with children like I did in Guatemala. As for the empty frames, I hope to fill them with the people I will meet: a family of my own and the families I desire to help, through a career I have yet to decide.

Ah. Now we get it. She’s connected the dots.

2.) Showing then telling gives you an opportunity to set-up your essay for what I believe to be the single most important element to any personal statement: insight.

#37 Provide insight

What is insight? In simple terms, it’s a deeper intuitive understanding of a person or thing.

But here’s a more useful definition for your college essay: Insight is something that you’ve noticed about the world that others may have missed. Insight answers the question: So what? It’s proof that you’re a close observer of the world. That you’re sensitive to details. That you’re smart.

And the author of this essay doesn’t just give insight at the end of her essay, she does it at the beginning too: she begins with a description of herself creating a scrapbook (show), then follows this with a clear explanation for why she has just described this (tell).

Final note: it’s important to use insight judiciously. Not throughout your whole essay; a couple times will do.

#38 Trim the fat.

Here’s a 40-word sentence. Can you cut it in half without changing the meaning?

Over the course of the six weeks, I became very familiar with playing the cello, the flute, the trumpet, and the marimba in the morning session while I continually learned how to play the acoustic guitar in the afternoon sessions.

Wait, actually try cutting this (in your mind) before scrolling down. See how concise you can get it.

Okay, here’s one way to revise it:

In six weeks, I learned the cello, flute, trumpet, and marimba in the mornings and acoustic guitar in the afternoons.

There. Half the words and retains the meaning.

#39 Split long sentences with complex ideas into two.

This may sound contrary to the first point but it ain’t. Why? Sometimes we’re just trying to pack too much into the same sentence.

Check this one out:

For an inquisitive student like me, Brown’s liberal program provides a diverse and intellectually stimulating environment, giving me great freedom to tailor my education by pursuing a double concentration in both public health and business, while also being able to tap into other, more unconventional, academic interests, such as ancient history and etymology through the first year seminars.

That’s a lot for one sentence, eh?

This sentence is what I’d call “top heavy.” It has a lot of important information in the first half–so much, in fact, that I need a break before I can take in the bits at the end about “ancient history” and “etymology.” Two options for revising this:

Option 1. If you find yourself trying to pack a lot into one sentence, just use two.

Two sentences work just as well, and require no extra words. In the example above, the author could write:

For an inquisitive student like me, Brown’s liberal program provides a diverse and intellectually stimulating environment, giving me great freedom to tailor my education by pursuing a double concentration in both public health and business. I also look forward to pursuing other, more unconventional, academic interests, such as ancient history and etymology through the first year seminars.

Option 2: Just trim the first half of the sentence to its essence, or cut most of it.

That might look like this:

At Brown I look forward to pursuing a double concentration in both public health and business, while also tapping into other, more unconventional academic interests, such as ancient history and etymology.

And just for the record (for all the counselors who might be wondering), I don’t actually write out these revisions for my students; I ask questions and let them figure it out. In this example, for instance, I highlighted the first half of the sentence and wrote, “Can you make this more concise?”

SAT / ACT Prep Online Guides and Tips

How to Write a Great College Essay, Step-by-Step

Writing your personal statement for your college application is an undeniably overwhelming project. Your essay is your big shot to show colleges who you are—it’s totally reasonable to get stressed out. But don’t let that stress paralyze you.

This guide will walk you through each step of the essay writing process to help you understand exactly what you need to do to write the best possible personal statement. I’m also going to follow an imaginary student named Eva as she plans and writes her college essay, from her initial organization and brainstorming to her final edits. By the end of this article, you’ll have all the tools you need to create a fantastic, effective college essay.

So how do you write a good college essay? The process starts with finding the best possible topic, which means understanding what the prompt is asking for and taking the time to brainstorm a variety of options. Next, you’ll determine how to create an interesting essay that shows off your unique perspective and write multiple drafts in order to hone your structure and language. Once your writing is as effective and engaging as possible, you’ll do a final sweep to make sure everything is correct.

This guide covers the following steps:

Step 1: Get Organized

The first step in how to write a college essay is figuring out what you actually need to do. Although many schools are now on the Common App, some very popular colleges, including University of Texas and University of California, still have their own applications and writing requirements. Even for Common App schools, you may need to write a supplemental essay or provide short answers to questions.

Before you get started, you should know exactly what essays you need to write. Having this information allows you to plan the best approach to each essay and helps you cut down on work by determining whether you can use an essay for more than one prompt.

Start Early

Writing good college essays involves a lot of work: you need dozens of hours to get just one personal statement properly polished, and that’s before you even start to consider any supplemental essays.

In order to make sure you have plenty of time to brainstorm, write, and edit your essay (or essays), I recommend starting at least two months before your first deadline. The last thing you want is to end up with a low-quality essay you aren’t proud of because you ran out of time and had to submit something unfinished.

Determine What You Need to Do

As I touched on above, each college has its own essay requirements, so you’ll need to go through and determine what exactly you need to submit for each school. This process is simple if you’re only using the Common App, since you can easily view the requirements for each school under the «My Colleges» tab. Watch out, though, because some schools have a dedicated «Writing Supplement» section, while others (even those that want a full essay) will put their prompts in the «Questions» section.

It gets trickier if you’re applying to any schools that aren’t on the Common App. You’ll need to look up the essay requirements for each college—what’s required should be clear on the application itself, or you can look under the «how to apply» section of the school’s website.

Once you’ve determined the requirements for each school, I recommend making yourself a chart with the school name, word limit, and application deadline on one side and the prompt or prompts you need to respond to on the other. That way you’ll be able to see exactly what you need to do and when you need to do it by.

Decide Where to Start

If you have one essay that’s due earlier than the others, start there. Otherwise, start with the essay for your top choice school.

I would also recommend starting with a longer personal statement before moving on to shorter supplementary essays, since the 500-700 word essays tend to take quite a bit longer than 100-250 word short responses. The brainstorming you do for the long essay may help you come up with ideas you like for the shorter ones as well.

Also consider whether some of the prompts are similar enough that you could submit the same essay to multiple schools. Doing so can save you some time and let you focus on a few really great essays rather than a lot of mediocre ones.

However, don’t reuse essays for dissimilar or very school-specific prompts, especially «why us» essays. If a college asks you to write about why you’re excited to go there, admissions officers want to see evidence that you’re genuinely interested. Reusing an essay about another school and swapping out the names is the fastest way to prove you aren’t.

Example: Eva’s College List

Eva is applying early to Emory University and regular decision to University of Washington, UCLA, and Reed College. Emory and Reed both use the Common App, while University of Washington, Emory, and Reed all use the Coalition App.

(SELECT 4)

1. Describe an example of your leadership experience in which you have positively influenced others, helped resolve disputes, or contributed to group efforts over time.

2. Every person has a creative side, and it can be expressed in many ways: problem solving, original and innovative thinking, and artistically, to name a few. Describe how you express your creative side.

3. What would you say is your greatest talent or skill? How have you developed and demonstrated that talent over time?

4. Describe how you have taken advantage of a significant educational opportunity or worked to overcome an educational barrier you have faced.

5. Describe the most significant challenge you have faced and the steps you have taken to overcome this challenge. How has this challenge affected your academic achievement?

6. Think about an academic subject that inspires you. Describe how you have furthered this interest inside and/or outside of the classroom.

7. What have you done to make your school or your community a better place?

8. Beyond what has already been shared in your application, what do you believe makes you stand out as a strong candidate for admissions to the University of California?

Even though she’s only applying to four schools, Eva has a lot to do: two essays for UW, four for the UC application, one for the Common App (or the Coalition App), two essays for Emory, plus the supplements. Many students will have fewer requirements to complete, but those who are applying to very selective schools or a number of schools on different applications will have as many or even more responses to write.

Since Eva’s first deadline is early decision for Emory, she’ll start by writing the Common App essay, and then work on the Emory supplements. (For the purposes of this post, we’ll focus on the Common App essay.)

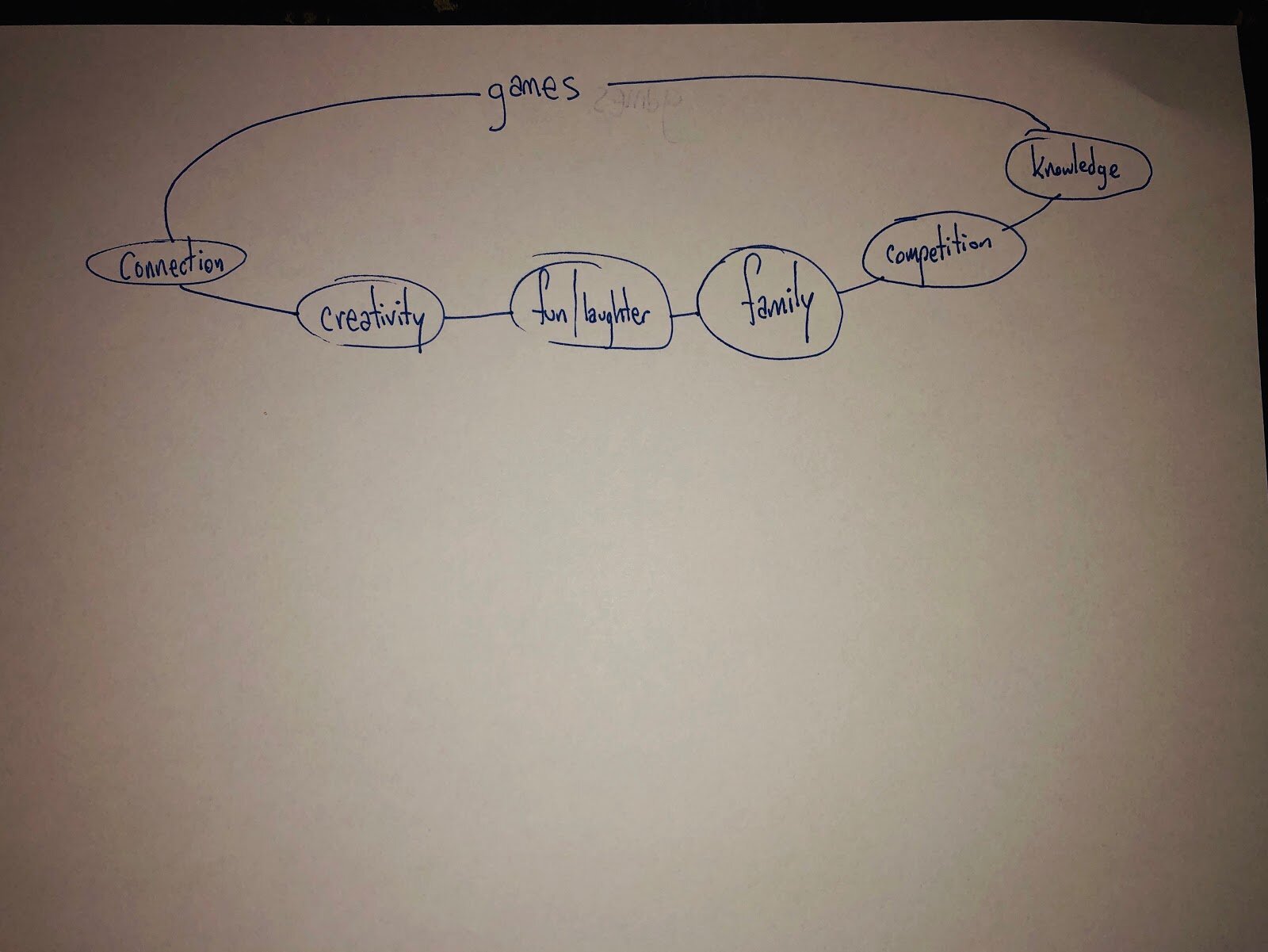

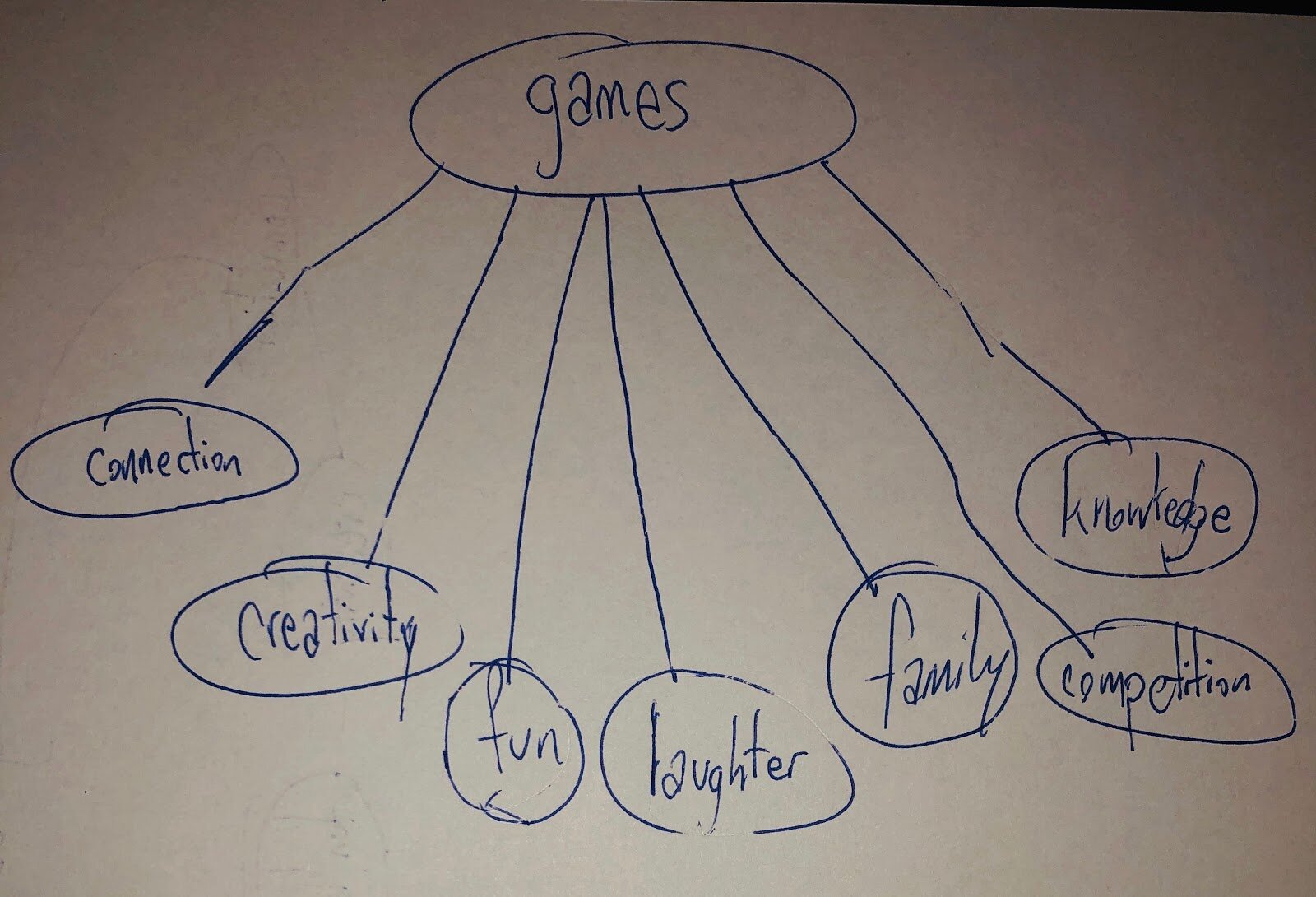

Step 2: Brainstorm

Next up in how to write a college essay: brainstorming essay ideas. There are tons of ways to come up with ideas for your essay topic: I’ve outlined three below. I recommend trying all of them and compiling a list of possible topics, then narrowing it down to the very best one or, if you’re writing multiple essays, ones.

Keep in mind as you brainstorm that there’s no best college essay topic, just the best topic for you. Don’t feel obligated to write about something because you think you should—those types of essays tend to be boring and uninspired. Similarly, don’t simply write about the first idea that crosses your mind because you don’t want to bother trying to think of something more interesting. Take the time to come up with a topic you’re really excited about and that you can write about in detail.

Want to write the perfect college application essay? Get professional help from PrepScholar.

Your dedicated PrepScholar Admissions counselor will craft your perfect college essay, from the ground up. We’ll learn your background and interests, brainstorm essay topics, and walk you through the essay drafting process, step-by-step. At the end, you’ll have a unique essay that you’ll proudly submit to your top choice colleges.

Don’t leave your college application to chance. Find out more about PrepScholar Admissions now:

Analyze the Prompts

One way to find possible topics is to think deeply about the college’s essay prompt. What are they asking you for? Break them down and analyze every angle.

Does the question include more than one part? Are there multiple tasks you need to complete?

What do you think the admissions officers are hoping to learn about you?

In cases where you have more than one choice of prompt, does one especially appeal to you? Why?

Let’s dissect one of the University of Washington prompts as an example:

«Our families and communities often define us and our individual worlds. Community might refer to your cultural group, extended family, religious group, neighborhood or school, sports team or club, co-workers, etc. Describe the world you come from and how you, as a product of it, might add to the diversity of the UW. «

This question is basically asking how your personal history, such as your childhood, family, groups you identify with etc. helped you become the person you are now. It offers a number of possible angles.

You can talk about the effects of either your family life (like your relationship with your parents or what your household was like growing up) or your cultural history (like your Jewish faith or your Venezuelan heritage). You can also choose between focusing on positive or negative effects of your family or culture. No matter what however, the readers definitely want to hear about your educational goals (i.e. what you hope to get out of college) and how they’re related to your personal experience.

As you try to think of answers for a prompt, imagine about what you would say if you were asked the question by a friend or during a get-to-know-you icebreaker. After all, admissions officers are basically just people who you want to get to know you.

The essay questions can make a great jumping off point, but don’t feel married to them. Most prompts are general enough that you can come up with an idea and then fit it to the question.

Consider Important Experiences, Events, and Ideas in Your Life

What experience, talent, interest or other quirk do you have that you might want to share with colleges? In other words, what makes you you? Possible topics include hobbies, extracurriculars, intellectual interests, jobs, significant one-time events, pieces of family history, or anything else that has shaped your perspective on life.

Unexpected or slightly unusual topics are often the best: your passionate love of Korean dramas or your yearly family road trip to an important historical site. You want your essay to add something to your application, so if you’re an All-American soccer player and want to write about the role soccer has played in your life, you’ll have a higher bar to clear.

Of course if you have a more serious part of your personal history—the death of a parent, serious illness, or challenging upbringing—you can write about that. But make sure you feel comfortable sharing details of the experience with the admissions committee and that you can separate yourself from it enough to take constructive criticism on your essay.

Think About How You See Yourself

The last brainstorming method is to consider whether there are particular personality traits you want to highlight. This approach can feel rather silly, but it can also be very effective.

If you were trying to sell yourself to an employer, or maybe even a potential date, how would you do it? Try to think about specific qualities that make you stand out. What are some situations in which you exhibited this trait?

Example: Eva’s Ideas

Looking at the Common App prompts, Eva wasn’t immediately drawn to any of them, but after a bit of consideration she thought it might be nice to write about her love of literature for the first one, which asks about something «so meaningful your application would be incomplete without it.» Alternatively, she liked the specificity of the failure prompt and thought she might write about a bad job interview she had had.

In terms of important events, Eva’s parents got divorced when she was three and she’s been going back and forth between their houses for as long as she can remember, so that’s a big part of her personal story. She’s also played piano for all four years of high school, although she’s not particularly good.

As for personal traits, Eva is really proud of her curiosity—if she doesn’t know something, she immediately looks it up, and often ends up discovering new topics she’s interested in. It’s a trait that’s definitely come in handy as a reporter for her school paper.

Step 3: Narrow Down Your List

Now you have a list of potential topics, but probably no idea where to start. The next step is to go through your ideas and determine which one will make for the strongest essay. You’ll then begin thinking about how best to approach it.

What to Look for in a College Essay Topic

There’s no single answer to the question of what makes a great college essay topic, but there are some key factors you should keep in mind. The best essays are focused, detailed, revealing and insightful, and finding the right topic is vital to writing a killer essay with all of those qualities.

As you go through your ideas, be discriminating—really think about how each topic could work as an essay. But don’t be too hard on yourself; even if an idea may not work exactly the way you first thought, there may be another way to approach it. Pay attention to what you’re really excited about and look for ways to make those ideas work.

Consideration 1: Does It Matter to You?

If you don’t care about your topic, it will be hard to convince your readers to care about it either. You can’t write a revealing essay about yourself unless you write about a topic that is truly important to you.

But don’t confuse important to you with important to the world: a college essay is not a persuasive argument. The point is to give the reader a sense of who you are, not to make a political or intellectual point. The essay needs to be personal.

Similarly, a lot of students feel like they have to write about a major life event or their most impressive achievement. But the purpose of a personal statement isn’t to serve as a resume or a brag sheet—there are plenty of other places in the application for you to list that information. Many of the best essays are about something small because your approach to a common experience generally reveals a lot about your perspective on the world.

Mostly, your topic needs to have had a genuine effect on your outlook, whether it taught you something about yourself or significantly shifted your view on something else.

Consideration 2: Does It Tell the Reader Something Different About You?

Your essay should add something to your application that isn’t obvious elsewhere. Again, there are sections for all of your extracurriculars and awards; the point of the essay is to reveal something more personal that isn’t clear just from numbers and lists.

You also want to make sure that if you’re sending more than one essay to a school—like a Common App personal statement and a school-specific supplement—the two essays take on different topics.

Consideration 3: Is It Specific?

Your essay should ultimately have a very narrow focus. 650 words may seem like a lot, but you can fill it up very quickly. This means you either need to have a very specific topic from the beginning or find a specific aspect of a broader topic to focus on.

If you try to take on a very broad topic, you’ll end up with a bunch of general statements and boring lists of your accomplishments. Instead, you want to find a short anecdote or single idea to explore in depth.

Consideration 4: Can You Discuss It in Detail?

A vague essay is a boring essay—specific details are what imbue your essay with your personality. For example, if I tell my friend that I had a great dessert yesterday, she probably won’t be that interested. But if I explain that I ate an amazing piece of peach raspberry pie with flaky, buttery crust and filling that was both sweet and tart, she will probably demand to know where I obtained it (at least she will if she appreciates the joys of pie). She’ll also learn more about me: I love pie and I analyze deserts with great seriousness.

Given the importance of details, writing about something that happened a long time ago or that you don’t remember well isn’t usually a wise choice. If you can’t describe something in depth, it will be challenging to write a compelling essay about it.

You also shouldn’t pick a topic you aren’t actually comfortable talking about. Some students are excited to write essays about very personal topics, like their mother’s bipolar disorder or their family’s financial struggles, but others dislike sharing details about these kinds of experiences. If you’re a member of the latter group, that’s totally okay, just don’t write about one of these sensitive topics.

Still, don’t worry that every single detail has to be perfectly correct. Definitely don’t make anything up, but if you remember a wall as green and it was really blue, your readers won’t notice or care.

Consideration 5: Can It Be Related to the Prompt?

As long as you’re talking about yourself, there are very few ideas that you can’t tie back to one of the Common App or Coalition App prompts. But if you’re applying to a school with its own more specific prompt, or working on supplemental essays, making sure to address the question will be a greater concern.

Want to write the perfect college application essay? Get professional help from PrepScholar.

Your dedicated PrepScholar Admissions counselor will craft your perfect college essay, from the ground up. We’ll learn your background and interests, brainstorm essay topics, and walk you through the essay drafting process, step-by-step. At the end, you’ll have a unique essay that you’ll proudly submit to your top choice colleges.

Don’t leave your college application to chance. Find out more about PrepScholar Admissions now:

Deciding on a Topic

Once you’ve gone through the questions above, you should have good sense of what you want to write about. Hopefully, it’s also gotten you started thinking about how you can best approach that topic, but we’ll cover how to plan your essay more fully in the next step.

If after going through the narrowing process, you’ve eliminated all your topics, first look back over them: are you being too hard on yourself? Are there any that you really like, but just aren’t totally sure what angle to take on? If so, try looking at the next section and seeing if you can’t find a different way to approach it.

If you just don’t have an idea you’re happy with, that’s okay! Give yourself a week to think about it. Sometimes you’ll end up having a genius idea in the car on the way to school or while studying for your U.S. history test. Otherwise, try the brainstorming process again when you’ve had a break.

If, on the other hand, you have more than one idea you really like, consider whether any of them can be used for other essays you need to write.

Example: Picking Eva’s Topic

Eva immediately rules out writing about playing piano, because it sounds super boring to her, and it’s not something she is particularly passionate about. She also decides not to write about splitting time between her parents because she just isn’t comfortable sharing her feelings about it with an admissions committee.

She feels more positive about the other three, so she decides to think about them for a couple of days. She ends up ruling out the job interview because she just can’t come up with that many details she could include.

She’s excited about both of her last two ideas, but sees issues with both of them: the books idea is very broad and the reporting idea doesn’t seem to apply to any of the prompts. Then she realizes that she can address the solving a problem prompt by talking about a time she was trying to research a story about the closing of a local movie theater, so she decides to go with that topic.

Step 4: Figure Out Your Approach

You’ve decided on a topic, but now you need to turn that topic into an essay. To do so, you need to determine what specifically you’re focusing on and how you’ll structure your essay.

If you’re struggling or uncertain, try taking a look at some examples of successful college essays. It can be helpful to dissect how other personal statements are structured to get ideas for your own, but don’t fall into the trap of trying to copy someone else’s approach. Your essay is your story—never forget that.

Let’s go through the key steps that will help you turn a great topic into a great essay.

Choose a Focal Point

As I touched on above, the narrower your focus, the easier it will be to write a unique, engaging personal statement. The simplest way to restrict the scope of your essay is to recount an anecdote, i.e. a short personal story that illustrates your larger point.

For example, say a student was planning to write about her Outward Bound trip in Yosemite. If she tries to tell the entire story of her trip, her essay will either be far too long or very vague. Instead, she decides to focus in on a specific incident that exemplifies what mattered to her about the experience: her failed attempt to climb Half Dome. She described the moment she decided to turn back without reaching the top in detail, while touching on other parts of the climb and trip where appropriate. This approach lets her create a dramatic arc in just 600 words, while fully answering the question posed in the prompt (Common App prompt 2).

Of course, concentrating on an anecdote isn’t the only way to narrow your focus. Depending on your topic, it might make more sense to build your essay around an especially meaningful object, relationship, or idea.

Another approach our example student from above could take to the same general topic would be to write about the generosity of fellow hikers (in response to Common App prompt 4). Rather than discussing a single incident, she could tell the story of her trip through times she was supported by other hikers: them giving tips on the trails, sharing snacks, encouraging her when she was tired, etc. A structure like this one can be trickier than the more straightforward anecdote approach, but it can also make for an engaging and different essay.

When deciding what part of your topic to focus on, try to find whatever it is about the topic that is most meaningful and unique to you. Once you’ve figured that part out, it will guide how you structure the essay.

Decide What You Want to Show About Yourself

Remember that the point of the college essay isn’t just to tell a story, it’s to show something about yourself. It’s vital that you have a specific point you want to make about what kind of person you are, what kind of college student you’d make, or what the experience you’re describing taught you.

Since the papers you write for school are mostly analytical, you probably aren’t used to writing about your own feelings. As such, it can be easy to neglect the reflection part of the personal statement in favor of just telling a story. Yet explaining what the event or idea you discuss meant to you is the most important essay—knowing how you want to tie your experiences back to your personal growth from the beginning will help you make sure to include it.

Develop a Structure

It’s not enough to just know what you want to write about—you also need to have a sense of how you’re going to write about it. You could have the most exciting topic of all time, but without a clear structure your essay will end up as incomprehensible gibberish that doesn’t tell the reader anything meaningful about your personality.

There are a lot of different possible essay structures, but a simple and effective one is the compressed narrative, which builds on a specific anecdote (like the Half Dome example above):

Start in the middle of the action. Don’t spend a lot of time at the beginning of your essay outlining background info—it doesn’t tend to draw the reader in and you usually need less of it than you think you do. Instead start right where your story starts to get interesting. (I’ll go into how to craft an intriguing opener in more depth below.)

Briefly explain what the situation is. Now that you’ve got the reader’s attention, go back and explain anything they need to know about how you got into this situation. Don’t feel compelled to fit everything in—only include the background details that are necessary to either understand what happened or illuminate your feelings about the situation in some way.

Finish the story. Once you’ve clarified exactly what’s going on, explain how you resolved the conflict or concluded the experience.

Explain what you learned. The last step is to tie everything together and bring home the main point of your story: how this experience affected you.

The key to this type of structure is to create narrative tension—you want your reader to be wondering what happens next.

A second approach is the thematic structure, which is based on returning to a key idea or object again and again (like the boots example above):

Establish the focus. If you’re going to structure your essay around a single theme or object, you need to begin the essay by introducing that key thing. You can do so with a relevant anecdote or a detailed description.

Touch on 3-5 times the focus was important. The body of your essay will consist of stringing together a few important moments related to the topic. Make sure to use sensory details to bring the reader into those points in time and keep her engaged in the essay. Also remember to elucidate why these moments were important to you.

Revisit the main idea. At the end, you want to tie everything together by revisiting the main idea or object and showing how your relationship to it has shaped or affected you. Ideally, you’ll also hint at how this thing will be important to you going forward.

To make this structure work you need a very specific focus. Your love of travel, for example, is much too broad—you would need to hone in on a specific aspect of that interest, like how traveling has taught you to adapt to event the most unusual situations. Whatever you do, don’t use this structure to create a glorified resume or brag sheet.

However you structure your essay, you want to make sure that it clearly lays out both the events or ideas you’re describing and establishes the stakes (i.e. what it all means for you). Many students become so focused on telling a story or recounting details that they forget to explain what it all meant to them.

Example: Eva’s Essay Plan

For her essay, Eva decides to use the compressed narrative structure to tell the story of how she tried and failed to report on the closing of a historic movie theater:

Step 5: Write a First Draft

The key to writing your first draft is not to worry about whether it’s any good—just get something on paper and go from there. You will have to rewrite, so trying to get everything perfect is both frustrating and futile.

Everyone has their own writing process. Maybe you feel more comfortable sitting down and writing the whole draft from beginning to end in one go. Maybe you jump around, writing a little bit here and a little there. It’s okay to have sections you know won’t work or to skip over things you think you’ll need to include later.

Whatever your approach, there are a few tips everyone can benefit from.

Don’t Aim for Perfection

I mentioned this idea above, but I can’t emphasize it enough: no one writes a perfect first draft. Extensive editing and rewriting is vital to crafting an effective personal statement. Don’t get too attached to any part of your draft, because you may need to change anything (or everything) about your essay later.

Also keep in mind that, at this point in the process, the goal is just to get your ideas down. Wonky phrasings and misplaced commas can easily be fixed when you edit, so don’t worry about them as you write. Instead, focus on including lots of specific details and emphasizing how your topic has affected you, since these aspects are vital to a compelling essay.

Want to write the perfect college application essay? Get professional help from PrepScholar.

Your dedicated PrepScholar Admissions counselor will craft your perfect college essay, from the ground up. We’ll learn your background and interests, brainstorm essay topics, and walk you through the essay drafting process, step-by-step. At the end, you’ll have a unique essay that you’ll proudly submit to your top choice colleges.

Don’t leave your college application to chance. Find out more about PrepScholar Admissions now:

Write an Engaging Introduction

One part of the essay you do want to pay special attention to is the introduction. Your intro is your essay’s first impression: you only get one. It’s much harder to regain your reader’s attention once you’ve lost it, so you want to draw the reader in with an immediately engaging hook that sets up a compelling story.

There are two possible approaches I would recommend.

The «In Media Res» Opening

You’ll probably recognize this term if you studied The Odyssey: it basically means that the story starts in the middle of the action, rather than at the beginning. A good intro of this type makes the reader wonder both how you got to the point you’re starting at and where you’ll go from there. These openers provide a solid, intriguing beginning for narrative essays (though they can certainly for thematic structures as well).

But how do you craft one? Try to determine the most interesting point in your story and start there. If you’re not sure where that is, try writing out the entire story and then crossing out each sentence in order until you get to one that immediately grabs your attention.

Here’s an example from a real student’s college essay:

«I strode in front of 400 frenzied eighth graders with my arm slung over my Fender Stratocaster guitar—it actually belonged to my mother—and launched into the first few chords of Nirvana’s ‘Lithium.'»

Anonymous, University of Virginia

This intro throws the reader right into the middle of the action. The author jumps right into the action: the performance. You can imagine how much less exciting it would be if the essay opened with an explanation of what the event was and why the author was performing.

The Specific Generalization

Sounds like an oxymoron, right? This type of intro sets up what the essay is going to talk about in a slightly unexpected way. These are a bit trickier than the «in media res» variety, but they can work really well for the right essay—generally one with a thematic structure.

The key to this type of intro is detail. Contrary to what you may have learned in elementary school, sweeping statements don’t make very strong hooks. If you want to start your essay with a more overall description of what you’ll be discussing, you still need to make it specific and unique enough to stand out.

Once again, let’s look at some examples from real students’ essays:

Neha, Johns Hopkins University

Brontë, Johns Hopkins University

Both of these intros set up the general topic of the essay (the first writer’s bookshelf and and the second’s love of Jane Eyre) in an intriguing way. The first intro works because it mixes specific descriptions («pushed against the left wall in my room») with more general commentary («a curious piece of furniture»). The second draws the reader in by adopting a conversational and irreverent tone with asides like «if you ask me» and «This may or may not be a coincidence.»

Don’t Worry Too Much About the Length

When you start writing, don’t worry about your essay’s length. Instead, focus on trying to include all of the details you can think of about your topic, which will make it easier to decide what you really need to include when you edit.

However, if your first draft is more than twice the word limit and you don’t have a clear idea of what needs to be cut out, you may need to reconsider your focus—your topic is likely too broad. You may also need to reconsider your topic or approach if you find yourself struggling to fill space, since this usually indicates a topic that lacks a specific focus.

Eva’s First Paragraph

I dialed the phone number for the fourth time that week. «Hello? This is Eva Smith, and I’m a reporter with Tiny Town High’s newspaper The Falcon. I was hoping to ask you some questions about—» I heard the distinctive click of the person on the other end of the line hanging up, followed by dial tone. I was about ready to give up: I’d been trying to get the skinny on whether the Atlas Theater was actually closing to make way for a big AMC multiplex or if it was just a rumor for weeks, but no one would return my calls.

Step 6: Edit Aggressively

No one writes a perfect first draft. No matter how much you might want to be done after writing a first draft—you must take the time to edit. Thinking critically about your essay and rewriting as needed is a vital part of writing a great college essay.

Before you start editing, put your essay aside for a week or so. It will be easier to approach it objectively if you haven’t seen it in a while. Then, take an initial pass to identify any big picture issues with your essay. Once you’ve fixed those, ask for feedback from other readers—they’ll often notice gaps in logic that don’t appear to you, because you’re automatically filling in your intimate knowledge of the situation. Finally, take another, more detailed look at your essay to fine tune the language.

I’ve explained each of these steps in more depth below.

First Editing Pass

You should start the editing process by looking for any structural or thematic issues with your essay. If you see sentences that don’t make sense or glaring typos of course fix them, but at this point, you’re really focused on the major issues since those require the most extensive rewrites. You don’t want to get your sentences beautifully structured only to realize you need to remove the entire paragraph.

This phase is really about honing your structure and your voice. As you read through your essay, think about whether it effectively draws the reader along, engages him with specific details, and shows why the topic matters to you. Try asking yourself the following questions:

Give yourself credit for what you’ve done well, but don’t hesitate to change things that aren’t working. It can be tempting to hang on to what you’ve already written—you took the time and thought to craft it in the first place, so it can be hard to let it go. Taking this approach is doing yourself a disservice, however. No matter how much work you put into a paragraph or much you like a phrase, if they aren’t adding to your essay, they need to be cut or altered.

If there’s a really big structural problem, or the topic is just not working, you may have to chuck this draft out and start from scratch. Don’t panic! I know starting over is frustrating, but it’s often the best way to fix major issues.

Consulting Other Readers

Once you’ve fixed the problems you found on the first pass and have a second (or third) draft you’re basically happy with, ask some other people to read it. Check with people whose judgment you trust: parents, teachers, and friends can all be great resources, but how helpful someone will be depends on the individual and how willing you are to take criticism from her.

Also, keep in mind that many people, even teachers, may not be familiar with what colleges look for in an essay. Your mom, for example, may have never written a personal statement, and even if she did, it was most likely decades ago. Give your readers a sense of what you’d like them to read for, or print out the questions I listed above and include them at the end of your essay.

Second Pass

After incorporating any helpful feedback you got from others, you should now have a nearly complete draft with a clear arc.

At this point you want to look for issues with word choice and sentence structure:

A good way to check for weirdness in language is to read the essay out loud. If something sounds weird when you say it, it will almost certainly seem off when someone else reads it.

Example: Editing Eva’s First Paragraph

In general, Eva feels like her first paragraph isn’t as engaging as it could be and doesn’t introduce the main point of the essay that well: although it sets up the narrative, it doesn’t show off her personality that well. She decides to break it down sentence by sentence:

I dialed the phone number for the fourth time that week.

Problem: For a hook, this sentence is a little too expository. It doesn’t add any real excitement or important information (other than that this call isn’t the first, which can be incorporate elsewhere.

Solution: Cut this sentence and start with the line of dialogue.

«Hello? This is Eva Smith, and I’m a reporter with Tiny Town High’s newspaper The Falcon. I was hoping to ask you some questions about—»

Problem: No major issues with this sentence. It’s engaging and sets the scene effectively.