How wine is made

How wine is made

How wine is made

An illustrated guide to the winemaking process, by Jamie Goode

It all starts with grapes on the vine: and it’s important that these are properly ripe. Not ripe enough, or too ripe, and the wine will suffer. The grapes as they are harvested contain the potential of the wine: you can make a bad wine from good grapes, but not a good wine from bad grapes.

Teams of pickers head into the vineyard. This is the exciting time of year, and all winegrowers hope for good weather conditions during harvest. Bad weather can ruin things completely.

Hand-picked grapes being loaded into a half-ton bin.

Increasingly, grapes are being machine harvested. This is more cost-effective, and in warm regions quality can be preserved by picking at night, when it is cooler. This is much easier to do by machine.

The harvester plucks the grape berries off the vine and then dumps them into bins to go to the winery. This is in Bordeaux.

These are machine-picked grapes being sorted for quality.

Hand-picked grapes arriving as whole bunches in the winery.

Sorting hand-picked grapes for quality. Any rotten or raisined grapes, along with leaves and petioles, are removed.

These sorted grapes go to a machine that removes the stems. They may also be crushed, either just a little, or completely.

These are the stems that the grapes have been separated from in the destemmer.

Reception area at a small winery. Here grapes are being loaded and then taken by conveyor belt to a tank, from where they are being pumped into the fermentation vessel.

This is a very traditional winery, again, in the Douro. The red grapes have been foottrodden, and fermentation has begun naturally. These men are mixing up the skins and juice by hand: this process is carried out many times a day to help with extraction, and also to stop bacteria from growing on the cap of grape skins that naturally would float to the surface.

Sometimes cultured yeasts are added in dried form, to give the winemaker more control over the fermentation process. But many fermentations are still carried out with wild yeasts, naturally present in the vineyard or winery.

These red grapes are being fermented in a stainless steel tank. During fermentation, carbon dioxide is released so it is OK to leave the surface exposed. Sometimes, however, fermentation takes place in closed tanks with a vent to let the carbon dioxide escape.

In this small tank the cap of skins is being punched down using a robotic cap plunger. In some wineries this is done by hand, using poles.

An alternative to punch downs is to pump wine from the bottom of the tank back over the skins.

Here, fermenting red wine is being pumped out of the tank, and then pumped back in again. The idea is to introduce oxygen in the wine to help the yeasts in their growth. At other stages in winemaking care is taken to protect wine from oxygen, but at this stage it’s needed.

Once fermentation has finished, most red wines are then moved to barrels to complete their maturation. Barrels come in all shapes and sizes. Above is the most common size: 225-250 litres. The source of the oak, and whether or not the barrel has been used previously, is important in the effect it has on the developing wine.

This is a much larger, older barrel, imparting virtually no oak character to the wine. This suits some wine styles better than smaller barrels.

This is a basket press: once fermentation has completed and the young wine has been drained off the skins, the remaining skins and stems are pressed to extract the last of the wine that they contain.

This is a bladder press, used for some reds and almost all whites. A large bladder fills with air, pressing the contents gently and evenly, with gradually increasing pressure.

The inside of a tank that has been used to ferment white wine: the residue consists of dead yeasts cells.

Winemakers typically check the maturing red wine barrels at regular intervals, and top them up as some of the wine evaporates during the maturation process.

Occasionally it is necessary to move wine from one barrel to another, or from barrel to stainless steel tank. This cellar hand is using nitrogen gas to move the wine without exposing it to large amounts of oxygen.

Here wine is being moved from one barrel to another deliberately exposing it to oxygen to aid in the maturation process.

Some wines see no oak at all, but are kept in stainless steel tanks to preserve the fresh fruity characteristics.

Finally, the wine is ready and is prepared for bottling. Often, filtration is used to make the wine bright and clear, and to remove any risk of microbial spoilage. The glass on the left has been filtered; on the right you can see what it was like just before the process.

See How Wine is Made in Pictures (From Grapes to Glass)

A picture guide of how wine is made, from picking grapes to bottling wine.

Depending on the grape, the region and the kind of wine that a winemaker wishes to produce, the exact steps in the harvesting process will vary in time, technique and technology. But for the most part, every wine harvest includes these basic vine-to-wine steps:

Here’s a photo guide of each of the steps of how wine is made from the moment the grapes are picked until the wine is put into bottles. Enjoy!

Wine Harvest 101: From Grapes to Glass

1. Pick the grapes

Most vineyards will start with white grapes and then move to red varietals. The grapes are collected in bins or lugs and then transported to the crushing pad. This is where the process of turning grapes into juice and then into wine begins.

Man vs. Machine: The grapes are either cut from the vine by human hands with shears or they are removed by a machine.

Night Harvest vs Day Harvest: The grapes are either picked during the day or at night to maximize efficiency, beat the heat and capture grapes at stable sugar levels.

Get the Wine 101 Course ($50 value) FREE with the purchase of Wine Folly: Magnum Edition.

At this point in the process, the grapes are still intact with their stems—along with some leaves and sticks that made their way from the vineyards. These will all be removed in the next step.

2. Crush the grapes

No matter how or when the grapes were picked, they all get crushed in some fashion in the next step. The destemmer, which is a piece of winemaking machinery that does exactly what it says, removes the stems from the clusters and lightly crushes the grapes.

White Wine: Once crushed, the white grapes are transferred into a press, which is another piece of winemaking equipment that is literal to its name.

All of the grapes are pressed to extract the juice and leave behind the grape skins. The pure juice is then transferred into tanks where sediment settles to the bottom of the tank.

After a settling period, the juice is then “racked”, which means it’s filtered out of the settling tank into another tank to insure all the sediment is gone before fermentation starts.

Red Wine: Red wine grapes are also commonly destemmed and lightly crushed. The difference is that these grapes, along with their skins, go straight into a vat to start fermentation on their skins.

3. Fermenting Grapes into Wine

Simply put, fermentation is where the sugar converts into alcohol. There are plenty of techniques and technologies used during this process to accompany the different kinds of grapes. To keep things simple, this stage mainly includes:

4. Age the wine

Winemakers have lots of choices in this step, and again they all depend on the kind of wine one wants to create. Flavors in a wine become more intense due to several of these winemaking choices:

5. Bottle the wine

When the winemaker feels a wine has reached its full expression in aging, then it’s time to bottle the wine for consumption. And the rest is history, my friends.

Sources

Special thanks to the head winemakers, Tavis from Stone Hill Winery and Tom from Chandler Hill Vineyards.

Buy the book, get a course.

Get the Wine 101 Course ($50 value) FREE with the purchase of Wine Folly: Magnum Edition.

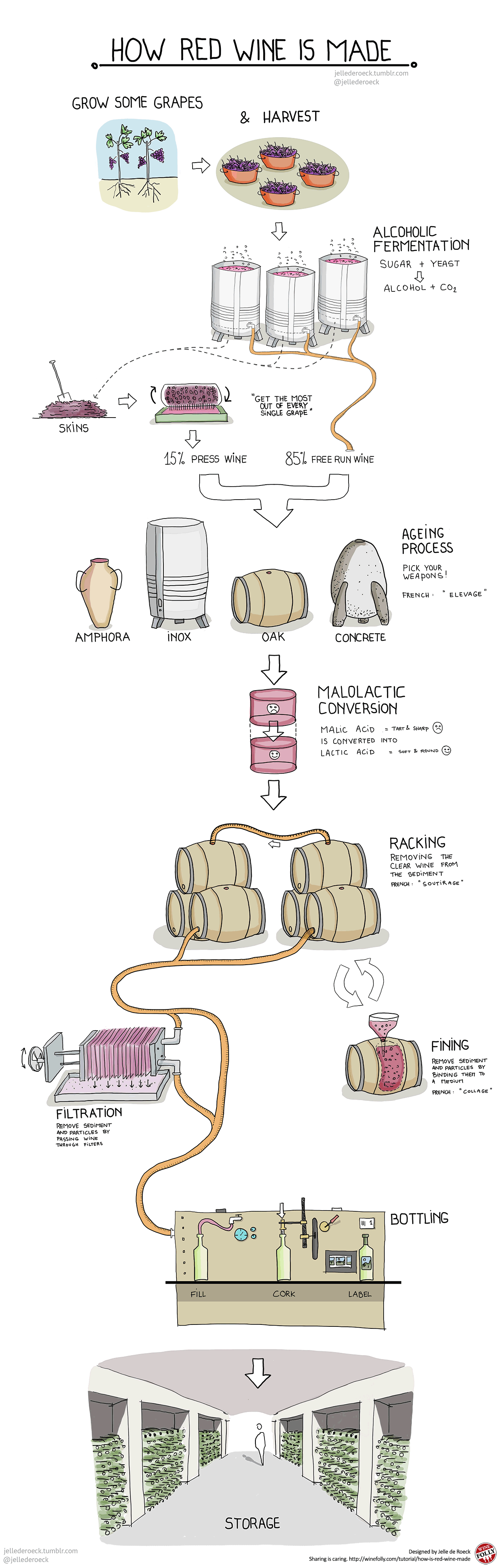

How Red Wine is Made Step by Step

Follow along to see how red wine is made, step-by-step, from grapes to glass. Surprisingly, not much has changed since we started making wine 8,000 years ago.

How Red Wine is Made: Follow Along Step by Step

Red winemaking differs from white winemaking in one important way: the juice ferments with grape skins to dye it red.

Of course, there’s more to red winemaking than the color. Learning about the process reveals secrets about quality and taste that will improve your palate. So, let’s walk through each of the steps of how red wine is made from grapes to glass.

Step 1: Harvest red wine grapes

Red wine is made with black (aka purple) wine grapes. In fact, all the color you see in a glass of red wine comes from anthocyanin (red pigment) found in black grape skins.

During the grape harvest, the most important thing to do is to pick the grapes at perfect ripeness. It’s critical because grapes don’t continue to ripen after they’ve been picked.

Get the Wine 101 Course ($50 value) FREE with the purchase of Wine Folly: Magnum Edition.

For all winemakers, the grape harvest season is the most critical (and very tense) time of year!

Step 2: Prepare grapes for fermentation

After the harvest, grapes head to the winery. The winemaker decides whether or not to remove the stems or to ferment grape bunches as whole clusters.

This is an important choice because leaving stems in the fermentation adds astringency (aka tannin) but also reduces sourness. As an example, Pinot Noir often ferments with whole clusters, but not Cabernet Sauvignon.

During this step, grapes also receive sulfur dioxide to stop bacterial spoilage before the fermentation starts. Check out this eye-opening article about sulfites and your health.

Step 3: Yeast starts the wine fermentation

What happens is small sugar-eating yeasts consume the grape sugars and make alcohol. The yeasts come either from a commercial packet (just like you might find in bread making), or occur spontaneously in the juice.

Spontaneous fermentation uses yeast found naturally on grapes!

Step 4: Alcoholic fermentation

Winemakers use many methods to tune the wine during fermentation.

For example, the fermenting juice gets frequently stirred to submerge the skins (they float!). One way to do this is to pump wine over the top. The other way is to punch down the “cap” of floating grape skins with a tool that looks like a giant potato masher.

Step 5: Press the wine

Most wines take 5–21 days to ferment sugar into alcohol. A few rare examples, such as Vin Santo and Amarone, take anywhere from 50 days to up to 4 years to fully ferment!

After the fermentation, vintners drain the freely running wine from the tank and put the remaining skins into a wine press. Pressing the skins gives winemakers about 15% more wine!

Step 6: Malolactic fermentation (aka “second fermentation”)

As the red wine settles in tanks or barrels, a second “fermentation” happens. A little microbe feasts on the wine acids and converts sharp-tasting malic acid into creamier, chocolatey lactic acid. (The same acid you find in greek yogurt!)

Nearly all red wines go through Malolactic Fermentation (MLF) but only a few white wines. One white wine we all know is Chardonnay. MLF is responsible for Chardonnay’s creamy and buttery flavors.

Step 7: Aging (aka “Elevage”)

Red wines age in a variety of storage vessels including wooden barrels, concrete, glass, clay, and stainless steel tanks. Each vessel affects wine differently as it ages.

Wooden barrels affect wine the most noticeably. The oak wood itself flavors the wine with natural compounds that smell like vanilla.

Unlined concrete and clay tanks have a softening effect on wine by reducing acidity.

Of course, the biggest thing that affects flavors in red wine is time. The longer a wine rests, the more chemical reactions happen within the liquid itself. Some describe red wines as tasting smoother and more nutty with age.

Step 8: Blending the wine

Now that the wine is good and rested, it’s time to make the final blend. A winemaker blends grape varieties together or different barrels of the same grape to make a finished wine.

Blending wine is a challenge because you have to use your sense of texture on your palate instead of your nose.

The tradition of blending created the many famous wine blends of the world!

Step 9: Clarifying the wine

One of the final steps of how a red wine is made is the clarification process. For this, many winemakers add clarifying or “fining” agents to remove suspended proteins in the wine (proteins make wine cloudy).

It’s pretty common to see winemakers use fining agents like casein or egg whites, but there is a growing group of winemakers using bentonite clay because it’s vegan.

Then, the wine gets passed through a filter for sanitation. This is important because it reduces the likelihood of bacterial spoilage.

Of course, a large group of fine winemakers do not fine or filter because they believe it removes texture and quality. Whether or not that’s true is something for you to decide.

Step 10: Bottling and labeling wines

Now, it’s time to bottle our wine. It’s very important to do this step with as little exposure to oxygen as possible. A small amount of sulfur dioxide is often added to help preserve the wine.

Step 11: Bottle aging

Finally, a few special wines continue to age in the winemaker’s cellar for years. In fact, if you look up different types of red wines (like Rioja or Brunello di Montalcino) you’ll discover that this step is considered essential for reserve bottlings.

So, the next time you open a bottle try to figure out what went into it!

Get The Winemaking Poster!

Support great wine education and share this poster with friends. It’s a fantastic way to expand your knowledge while tasting the good life. Made with love by Wine Folly in the USA.

Sources

Original infographic illustrated by architect, Jelle de Roeck

Metabolic responses to sulfur dioxide in grapevine Frontiers in Plant Science

Buy the book, get a course.

Get the Wine 101 Course ($50 value) FREE with the purchase of Wine Folly: Magnum Edition.

How Wine Is Made: Everything You Need to Know About Winemaking

McKenzie Hagan | March 26, 2020

A few things have changed since the days of using bare feet to press grapes, but you might be surprised to learn that many traditional winemaking methods remain the same.

This guide will walk you through the five essential steps of how wine is made, including how the grapes are harvested, the difference between making red wine and white wine, and why understanding the process will help you appreciate wine even more.

Harvesting the Grapes

When it comes to how wine is made, it all starts with plucking grapes from the vine. There are a few ways to go about this, either by employing people to pick the grapes by hand, or by using a picking machine.

The method for picking grapes doesn’t have much impact on the wine itself. While some may argue that hand-picked grapes reduce potential damage to the fruit and improve selection, using machines is often faster and cheaper. However, plenty of vineyards are on steep hillsides, making large, heavy machinery difficult to use.

Because many wine regions are based in hot climates, grape harvesting is often done at night to protect pickers from the hot sun. Once the grapes are picked, stems and all, they are then transported for crushing.

Crushing the Grapes

After the grapes are picked and gathered, they are put through a machine called a destemmer. This device (you guessed it) destems the grapes.

This grape juice is then filtered using a process called racking, which ensures that all the sediment — including grape skins and seeds — are gone.

By contrast, red and rosé wines are only lightly pressed before they’re fermented. This is because many of red wine’s qualities and character come from the tannins found in the grape skins and seeds. As such, they’re fermented with their skins on.

The Fermentation Process

Fermentation is probably the most critical step in wine production — it’s when alcohol is created. To trigger this chemical reaction, yeast is sometimes added into the tanks with the grapes. The added yeast converts the grape sugars into ethanol and carbon dioxide, giving the wine its alcohol content.

On the other hand, brands such as Usual Wines have chosen not to do this. Instead of hidden additives and potentially harmful chemicals, you’ll find wines made the Old-World way, in small batches from sustainably-farmed grapes without any additives.

For red and rosé wine, the grapes ferment with their skins on, giving them that iconic crimson color. While red wine grapes have contact with their skins from 5-14 days, rosé grapes only ferment with their skins on for a few hours, giving them a much lighter hue.

Red wine is fermented at a temperature of 70-85 degrees in large open vessels. While the wine ferments, winemakers use the open-topped vessels to punch down the grape skins, extracting more flavor.

White wine is a little simpler than red and rosé. Once white wine is racked, the clear grape juice is fermented at a lower heat, at just 45-60 degrees. This entire fermentation process takes several weeks to be completed.

The Maturation Process

The maturation process can add a host of complex flavors and textures to wine.

While some lower-quality red wines are matured in much cheaper stainless steel tanks, red wine is often matured in oak barrels. Because oak barrels are porous, they allow small amounts of oxygen to dissolve in the wine. This softens the harsh textures of the tannins and gives a smooth, oaky flavor.

There are a host of different barrels available to winemakers, each with their own qualities:

While the majority of white wines are fermented in stainless steel tanks, there are a few, such as Chardonnay, that use a red wine method of fermenting the wine in oak barrels.

Maturation periods depend on what the winemaker is trying to create. While some wines will mature for years upon years, others are designed to mature for a short amount of time — many will be on sale a few months after the grapes were harvested.

Fining, Bottling, and Corking

Once the wine has matured, it’s ready to be clarified, or “fined.” This process involves removing any unwanted particles from the wine, which could make it look cloudy or off-color. To achieve this, winemakers add a substance that binds to the unwanted particles, making them larger and therefore big enough to filter out.

After the fining process, the wine is bottled. Sterile glass wine bottles are filled from the bottom via a tube. While this process is commonly automated, some smaller wine producers will do this by hand.

Appreciating How Wine Is Made

As you can see, making wine is no small feat. Wine production is a long and arduous process, where much can go wrong.

It takes many pickers and large expensive machinery to harvest and prepare the grapes. After this, winemaking is a delicate science, as wine producers work tirelessly to press, ferment, and mature the humble grape into one of the world’s favorite drinks.

Using traditional, centuries-old techniques, wine producers use yeast and sugar to create alcohol. It takes years of knowledge to age their wine perfectly, giving it specific flavors and textures.

Remember, not all wine is created equal. While quality winemakers invest much time in these processes, many mass-produced wines are created by taking short cuts. For example, many vintners will include additives and artificial sweeteners to increase alcohol and speed up fermentation.

For wine that’s multifaceted, delicious, and lets the natural grape flavors be the star of the show, look for smaller independent winemakers. Then, the next time you take a sip of merlot, raise your glass and toast the winemakers of the world.

How Is Wine Made?

From picking to bottling, these are the steps grapes go through before reaching your glass.

Getty Images / Morsa Images

Pick, stomp, age—simple as that, right? Well, sort of. Although the process of making wine is relatively easy to grasp, there are so many more intricacies to vinification than meet the eye. Harvest decisions, fermentation choices, vinification methods, aging regimens and bottling options all play major roles in how a wine ends up tasting.

Although many winemakers believe that great wine is first made in the vineyard by growing high-quality grapes with great care, what happens in the cellar is just as important. We’ve outlined how wine is made, from picking the grapes to putting the final product into the bottle.

Harvest

» data-caption=»» data-expand=»300″ data-tracking-container=»true» />

Getty Images / Markus Gann / EyeEm

Getting fruit from the vineyard to the winery is the first step in the winemaking process. However, there are more decisions to be made here than you may think. First and foremost, choosing the ideal picking date is crucial. Winemakers regularly taste fruit from their vineyards throughout the year to assess acidity and sugar levels. When the time is deemed right, teams are gathered and sent out into the vines to collect the fruit.

Harvesting can be done one of two ways: either by hand or by machine. The former takes longer, though allows for more quality control and sorting in the vineyard (if desired). The latter is generally done at larger estates that have more ground to cover.

Crushing/Pressing the Grapes

» data-caption=»» data-expand=»300″ data-tracking-container=»true» />

This step is slightly different, depending on whether white, rosé, or orange or red wines are being made. First and foremost, if the winemaker desires, the grape berries are removed from their stems using a destemmer. Crushing follows. For white wines, fruit is generally crushed and pressed, meaning that juice is quickly removed from contact with the grape skins. Once pressed, the juice is then moved into a tank to settle, then racked off of the sediment.

For orange and red wines, the fruit is crushed (with or without stems) and left on the skins for a given period of time to macerate. This is what ultimately gives red and orange wines their color and tannin structure.

Fermentation

» data-caption=»» data-expand=»300″ data-tracking-container=»true» />

Getty Images / OceanProd

The equation of alcoholic fermentation is simple: Yeast plus sugar equals alcohol and CO2. Fermentations can be done with either native yeasts or cultivated yeasts. Native yeast fermentations (or spontaneous fermentations) are executed with naturally present yeasts found on grape skins and in a winery’s environment. Cultivated yeast fermentations are implemented by using purchased strains of yeast and adding them to the juice to execute the process. Spontaneous fermentations tend to take much longer and are often credited with producing more complex final wines.

Aging

» data-caption=»» data-expand=»300″ data-tracking-container=»true» />

Getty Images / Morsa Images

Several factors come into consideration when developing a wine’s aging (or élevage) regimen. First, the vessel decision is the big factor. Most winemakers will choose to age their wines in steel, cement or oak, although terra cotta or clay, glass and other vessels are also possible options.

Aging wine in steel creates a nonoxidative environment, meaning that wines are not exposed to oxygen. This tends to preserve fresh fruit-driven flavors in the wine, and no external tannins or flavor are added from wood. On the opposite side of the spectrum, oak aging creates an oxidative environment, meaning that the wine has contact with oxygen. This allows the wine to develop different levels of texture and flavors. When new oak (as opposed to neutral or used wood) is used, flavors of vanilla, baking spice, coconut and/or dill can often be tasted in the resulting wine.

Fining and/or Filtering the Wine

» data-caption=»» data-expand=»300″ data-tracking-container=»true» />

Getty Images / Stanislav Sablin

Post-aging, some winemakers will choose to fine and/or filter their wines to remove any residual sediment from the juice. Filtering is done through a porous material, whereas fining requires adding some sort of substance to the wine (generally bentonite, egg whites, gelatin or isinglass) to the wine and allowing the sediment to coagulate. Note that residual sediment in wine is absolutely harmless and is completely OK to drink. Winemakers who choose to fine and/or filter their wines generally only do these steps for aesthetic reasons.

Bottling

» data-caption=»» data-expand=»300″ data-tracking-container=»true» />

Getty Images / Alfio Manciagli

Once the wines are aged and fined and/or filtered, the wine is ultimately bottled and ready to be packaged. Some winemakers choose to additionally age their wines in the bottle for a given period of time prior to releasing them. Once bottled, the wines are labeled and sealed, with corks, screw caps or other closures, and are sent off to be delivered to your local watering hole or neighborhood retail shop.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/unnamed-a6bca6313fa84e4ca0922bad6d52e7e4.png)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/how-is-wine-made_main_MorsaImages_720x720-5894162aa0ae471ba68bb8870e0f033a.jpg)