Michael pollan how to change your mind

Michael pollan how to change your mind

Michael pollan how to change your mind

ALSO BY Michael Pollan

In Defense of Food

The Omnivore’s Dilemma

The Botany of Desire

A Place of My Own

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

Copyright © 2018 by Michael Pollan

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Image here and here from “Homological scaffolds of brain functional networks,” by G. Petri, P. Expert, F. Turkheimer, R. Carhart-Harris, D. Nutt, P. J. Hellyer, and F. Vaccarino, Journal of the Royal Society Interface, 2014.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Pollan, Michael, 1955– author.

Title: How to change your mind : what the new science of psychedelics teaches us about consciousness, dying, addiction, depression, and transcendence / Michael Pollan.

Description: New York : Penguin Press, 2018.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018006190 (print) | LCCN 2018010396 (ebook) | ISBN 9780525558941 (ebook) | ISBN 9781594204227 (hardback)

Subjects: LCSH: Pollan, Michael, 1955—Mental health. | Hallucinogenic drugs—Therapeutic use. | Psychotherapy patients—Biography. | BISAC: BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Science & Technology. | MEDICAL / Mental Health.

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018006190

NOTE: This book relates the author’s investigative reporting on, and related self-experimentation with, psilocybin mushrooms, the drug lysergic acid diethylamide (or, as it is more commonly known, LSD), and the drug 5-methoxy-N,N-dimethyltryptamine (more commonly known as 5-MeO-DMT or The Toad). It is a criminal offense in the United States and in many other countries, punishable by imprisonment and/or fines, to manufacture, possess, or supply LSD, psilocybin mushrooms, and/or the drug 5-MeO-DMT, except in connection with government-sanctioned research. You should therefore understand that this book is intended to convey the author’s experiences and to provide an understanding of the background and current state of research into these substances. It is not intended to encourage you to break the law and no attempt should be made to use these substances for any purpose except in a legally sanctioned clinical trial. The author and the publisher expressly disclaim any liability, loss, or risk, personal or otherwise, that is incurred as a consequence, directly or indirectly, of the contents of this book.

Certain names and locations have been changed in order to protect the author and others.

The soul should always stand ajar.

Also by Michael Pollan

Prologue: A New Door

Natural History: Bemushroomed

History: The First Wave

Part I: The Promise

Part II: The Crack-Up

Travelogue: Journeying Underground

Trip Two: Psilocybin

Trip Three: 5-MeO-DMT (or, The Toad)

The Neuroscience: Your Brain on Psychedelics

The Trip Treatment: Psychedelics in Psychotherapy

Coda: Going to Meet My Default Mode Network

Epilogue: In Praise of Neural Diversity

About the Author

MIDWAY THROUGH the twentieth century, two unusual new molecules, organic compounds with a striking family resemblance, exploded upon the West. In time, they would change the course of social, political, and cultural history, as well as the personal histories of the millions of people who would eventually introduce them to their brains. As it happened, the arrival of these disruptive chemistries coincided with another world historical explosion—that of the atomic bomb. There were people who compared the two events and made much of the cosmic synchronicity. Extraordinary new energies had been loosed upon the world; things would never be quite the same.

The first of these molecules was an accidental invention of science. Lysergic acid diethylamide, commonly known as LSD, was first synthesized by Albert Hofmann in 1938, shortly before physicists split an atom of uranium for the first time. Hofmann, who worked for the Swiss pharmaceutical firm Sandoz, had been looking for a drug to stimulate circulation, not a psychoactive compound. It wasn’t until five years later when he accidentally ingested a minuscule quantity of the new chemical that he realized he had created something powerful, at once terrifying and wondrous.

The second molecule had been around for thousands of years, though no one in the developed world was aware of it. Produced not by a chemist but by an inconspicuous little brown mushroom, this molecule, which would come to be known as psilocybin, had been used by the indigenous peoples of Mexico and Central America for hundreds of years as a sacrament. Called teonanácatl by the Aztecs, or “flesh of the gods,” the mushroom was brutally suppressed by the Roman Catholic Church after the Spanish conquest and driven underground. In 1955, twelve years after Albert Hofmann’s discovery of LSD, a Manhattan banker and amateur mycologist named R. Gordon Wasson sampled the magic mushroom in the town of Huautla de Jiménez in the southern Mexican state of Oaxaca. Two years later, he published a fifteen-page account of the “mushrooms that cause strange visions” in Life magazine, marking the moment when news of a new form of consciousness first reached the general public. (In 1957, knowledge of LSD was mostly confined to the community of researchers and mental health professionals.) People would not realize the magnitude of what had happened for several more years, but history in the West had shifted.

The impact of these two molecules is hard to overestimate. The advent of LSD can be linked to the revolution in brain science that begins in the 1950s, when scientists discovered the role of neurotransmitters in the brain. That quantities of LSD measured in micrograms could produce symptoms resembling psychosis inspired brain scientists to search for the neurochemical basis of mental disorders previously believed to be psychological in origin. At the same time, psychedelics found their way into psychotherapy, where they were used to treat a variety of disorders, including alcoholism, anxiety, and depression. For most of the 1950s and early 1960s, many in the psychiatric establishment regarded LSD and psilocybin as miracle drugs.

The arrival of these two compounds is also linked to the rise of the counterculture during the 1960s and, perhaps especially, to its particular tone and style. For the first time in history, th

e young had a rite of passage all their own: the “acid trip.” Instead of folding the young into the adult world, as rites of passage have always done, this one landed them in a country of the mind few adults had any idea even existed. The effect on society was, to put it mildly, disruptive.

Yet by the end of the 1960s, the social and political shock waves unleashed by these molecules seemed to dissipate. The dark side of psychedelics began to receive tremendous amounts of publicity—bad trips, psychotic breaks, flashbacks, suicides—and beginning in 1965 the exuberance surrounding these new drugs gave way to moral panic. As quickly as the culture and the scientific establishment had embraced psychedelics, they now turned sharply against them. By the end of the decade, psychedelic drugs—which had been legal in most places—were outlawed and forced underground. At least one of the twentieth century’s two bombs appeared to have been defused.

Then something unexpected and telling happened. Beginning in the 1990s, well out of view of most of us, a small group of scientists, psychotherapists, and so-called psychonauts, believing that something precious had been lost from both science and culture, resolved to recover it.

Today, after several decades of suppression and neglect, psychedelics are having a renaissance. A new generation of scientists, many of them inspired by their own personal experience of the compounds, are testing their potential to heal mental illnesses such as depression, anxiety, trauma, and addiction. Other scientists are using psychedelics in conjunction with new brain-imaging tools to explore the links between brain and mind, hoping to unravel some of the mysteries of consciousness.

One good way to understand a complex system is to disturb it and then see what happens. By smashing atoms, a particle accelerator forces them to yield their secrets. By administering psychedelics in carefully calibrated doses, neuroscientists can profoundly disturb the normal waking consciousness of volunteers, dissolving the structures of the self and occasioning what can be described as a mystical experience. While this is happening, imaging tools can observe the changes in the brain’s activity and patterns of connection. Already this work is yielding surprising insights into the “neural correlates” of the sense of self and spiritual experience. The hoary 1960s platitude that psychedelics offered a key to understanding—and “expanding”—consciousness no longer looks quite so preposterous.

How to Change Your Mind is the story of this renaissance. Although it didn’t start out that way, it is a very personal as well as public history. Perhaps this was inevitable. Everything I was learning about the third-person history of psychedelic research made me want to explore this novel landscape of the mind in the first person too—to see how the changes in consciousness these molecules wrought actually feel and what, if anything, they had to teach me about my mind and might contribute to my life.

THIS WAS, FOR ME, a completely unexpected turn of events. The history of psychedelics I’ve summarized here is not a history I lived. I was born in 1955, halfway through the decade that psychedelics first burst onto the American scene, but it wasn’t until the prospect of turning sixty had drifted into view that I seriously considered trying LSD for the first time. Coming from a baby boomer, that might sound improbable, a dereliction of generational duty. But I was only twelve years old in 1967, too young to have been more than dimly aware of the Summer of Love or the San Francisco Acid Tests. At fourteen, the only way I was going to get to Woodstock was if my parents drove me. Much of the 1960s I experienced through the pages of Time magazine. By the time the idea of trying or not trying LSD swam into my conscious awareness, it had already completed its speedy media arc from psychiatric wonder drug to counterculture sacrament to destroyer of young minds.

I must have been in junior high school when a scientist reported (mistakenly, as it turned out) that LSD scrambled your chromosomes; the entire media, as well as my health-ed teacher, made sure we heard all about it. A couple of years later, the television personality Art Linkletter began campaigning against LSD, which he blamed for the fact his daughter had jumped out of an apartment window, killing herself. LSD supposedly had something to do with the Manson murders too. By the early 1970s, when I went to college, everything you heard about LSD seemed calculated to terrify. It worked on me: I’m less a child of the psychedelic 1960s than of the moral panic that psychedelics provoked.

I also had my own personal reason for steering clear of psychedelics: a painfully anxious adolescence that left me (and at least one psychiatrist) doubting my grip on sanity. By the time I got to college, I was feeling sturdier, but the idea of rolling the mental dice with a psychedelic drug still seemed like a bad idea.

Years later, in my late twenties and feeling more settled, I did try magic mushrooms two or three times. A friend had given me a Mason jar full of dried, gnarly Psilocybes, and on a couple of memorable occasions my partner (now wife), Judith, and I choked down two or three of them, endured a brief wave of nausea, and then sailed off on four or five interesting hours in the company of each other and what felt like a wonderfully italicized version of the familiar reality.

Psychedelic aficionados would probably categorize what we had as a low-dose “aesthetic experience,” rather than a full-blown ego-disintegrating trip. We certainly didn’t take leave of the known universe or have what anyone would call a mystical experience. But it was really interesting. What I particularly remember was the preternatural vividness of the greens in the woods, and in particular the velvety chartreuse softness of the ferns. I was gripped by a powerful compulsion to be outdoors, undressed, and as far from anything made of metal or plastic as it was possible to get. Because we were alone in the country, this was all doable. I don’t recall much about a follow-up trip on a Saturday in Riverside Park in Manhattan except that it was considerably less enjoyable and unselfconscious, with too much time spent wondering if other people could tell that we were high.

I didn’t know it at the time, but the difference between these two experiences of the same drug demonstrated something important, and special, about psychedelics: the critical influence of “set” and “setting.” Set is the mind-set or expectation one brings to the experience, and setting is the environment in which it takes place. Compared with other drugs, psychedelics seldom affect people the same way twice, because they tend to magnify whatever’s already going on both inside and outside one’s head.

After those two brief trips, the mushroom jar lived in the back of our pantry for years, untouched. The thought of giving over a whole day to a psychedelic experience had come to seem inconceivable. We were working long hours at new careers, and those vast swaths of unallocated time that college (or unemployment) affords had become a memory. Now another, very different kind of drug was available, one that was considerably easier to weave into the fabric of a Manhattan career: cocaine. The snowy-white powder made the wrinkled brown mushrooms seem dowdy, unpredictable, and overly demanding. Cleaning out the kitchen cabinets one weekend, we stumbled upon the forgotten jar and tossed it in the trash, along with the exhausted spices and expired packages of food.

Fast-forward three decades, and I really wish I hadn’t done that. I’d give a lot to have a whole jar of magic mushrooms now. I’ve begun to wonder if perhaps these remarkable molecules might be wasted on the young, that they may have more to offer us later in life, after the cement of our mental habits and everyday behaviors has set. Carl Jung once wrote that it is not the young but people in middle age who need to have an “experience of the numinous” to help them negotiate the second half of their lives.

By the time I arrived safely in my fifties, life seemed to be running along a few deep but comfortable grooves: a long and happy marriage alongside an equally long and gratifying career. As we do, I had developed a set of fairly dependable mental algorithms for navigating whatever life threw at me, whether at home or at work. What was missing from my life? Nothing I could think of—until, that is, word of the

new research into psychedelics began to find its way to me, making me wonder if perhaps I had failed to recognize the potential of these molecules as a tool for both understanding the mind and, potentially, changing it.

HERE ARE THE THREE DATA POINTS that persuaded me this was the case.

In the spring of 2010, a front-page story appeared in the New York Times headlined “Hallucinogens Have Doctors Tuning In Again.” It reported that researchers had been giving large doses of psilocybin—the active compound in magic mushrooms—to terminal cancer patients as a way to help them deal with their “existential distress” at the approach of death.

These experiments, which were taking place simultaneously at Johns Hopkins, UCLA, and New York University, seemed not just improbable but crazy. Faced with a terminal diagnosis, the very last thing I would want to do is take a psychedelic drug—that is, surrender control of my mind and then in that psychologically vulnerable state stare straight into the abyss. But many of the volunteers reported that over the course of a single guided psychedelic “journey” they reconceived how they viewed their cancer and the prospect of dying. Several of them said they had lost their fear of death completely. The reasons offered for this transformation were intriguing but also somewhat elusive. “Individuals transcend their primary identification with their bodies and experience ego-free states,” one of the researchers was quoted as saying. They “return with a new perspective and profound acceptance.”

I filed that story away, until a year or two later, when Judith and I found ourselves at a dinner party at a big house in the Berkeley Hills, seated at a long table with a dozen or so people, when a woman at the far end of the table began talking about her acid trips. She looked to be about my age and, I learned, was a prominent psychologist. I was engrossed in a different conversation at the time, but as soon as the phonemes L-S-D drifted down to my end of the table, I couldn’t help but cup my ear (literally) and try to tune in.

Michael Pollan Drops Acid — and Comes Back From His Trip Convinced

Send any friend a story

As a subscriber, you have 10 gift articles to give each month. Anyone can read what you share.

Give this article

When you purchase an independently reviewed book through our site, we earn an affiliate commission.

Michael Pollan has long been concerned with the moral dilemmas of everyday life. “Second Nature,” his first book, was ostensibly about gardening, but really about ways to overcome our alienation from the natural world. “A Place of My Own,” his second, chronicled the “radically unhandy” Pollan’s construction of his writing studio. “The Botany of Desire,” his third and possibly greatest book, put him back in the garden, though in a more global state of mind. He then went on to write four searching books that wrestled, in one way or another, with the ethics of eating, one of which contained Pollan’s now widely shared haiku: “Eat food. Not too much. Mostly plants.”

Unlike many best-selling nonfiction writers, Pollan doesn’t write self-help books that cross-dress as narrative nonfiction. He’s entirely too skeptical for that. At the same time, though, he’s an often relentlessly sunny, affirmative writer. “In Defense of Food,” Pollan’s most polemical book, despairs of American eating habits, yet concludes with the dainty recommendation to eat local as often as possible. Pollan’s literary persona has a rare, almost Thoreauvian affect: the lovable scold.

With “How to Change Your Mind,” Pollan remains concerned with what we put into our bodies, but we’re not talking about arugula. At various points, our author ingests LSD, psilocybin and the crystallized venom of a Sonoran Desert toad. He writes, often remarkably, about what he experienced under the influence of these drugs. (The book comes fronted with a publisher’s disclaimer that nothing contained within is “intended to encourage you to break the law.” Whatever, Dad.) Before starting the book, Pollan, now in his early 60s, had never tried psychedelics, referring to himself as “less a child of the psychedelic 1960s than of the moral panic that psychedelics provoked.” But when he discovered that clinical interest had been revived in what some boosters are now calling entheogens (from the Greek for “the divine within”), he had to know: How did this happen, and what do these remarkable substances actually do to us?

Well, why does anyone take drugs? The simplest answer is that drugs are generally fun to take, until they aren’t. But psychedelics are different. They don’t drape you in marijuana’s gauzy haze or imbue you with cocaine’s wintry, italicized focus. They’re nothing like opioids, which balance the human body on a knife’s edge between pleasure and death. Psychedelics are to drugs what the Pyramids are to architecture — majestic, ancient and a little frightening. Pollan persuasively argues that our anxieties are misplaced when it comes to psychedelics, most of which are nonaddictive. They also fail to produce what Pollan calls the “physiological noise” of other psychoactive drugs. All things considered, LSD is probably less harmful to the human body than Diet Dr Pepper.

Disclaimer aside, nothing in Pollan’s book argues for the recreational use or abuse of psychedelic drugs. What it does argue is that psychedelic-aided therapy, properly conducted by trained professionals — what Pollan calls White-Coat Shamanism — can be personally transformative, helping with everything from overcoming addiction to easing the existential terror of the terminally ill. The strange thing is we’ve been here with psychedelics before.

LSD was first synthesized (from a grain fungus) in 1938, by a chemist working for the Swiss pharmaceutical firm Sandoz. A few years later, not having any idea what he’d created, the chemist accidentally dosed himself and went on to have a notably interesting afternoon. With LSD, Sandoz knew it had something on its hands, but wasn’t sure what. Its management decided to send out free samples to researchers on request, which went on for more than a decade. By the 1950s, scientists studying LSD had discovered serotonin, figured out that the human brain was full of something called neurotransmitters and begun inching toward the development of the first antidepressants. LSD showed such promise in treating alcoholism that the A.A. founder Bill Wilson considered including LSD treatment in his program. So-called magic mushrooms — and the mind-altering psilocybin they contain — arrived a bit later to the scene, having been reintroduced to the Western world thanks to a 1957 Life magazine article, but they proved just as rich in therapeutic possibilities.

All this ended thanks to the antics of Timothy Leary and other self-styled prophets of acid. By 1970, LSD had been outlawed and declared a Schedule 1 substance. Countercultural vanguards didn’t stop taking LSD, and “bad trip” entered the English lexicon. Psychedelics, it was concluded, sundered rather than opened minds, and any research that suggested otherwise was buried. Pollan describes several addiction scientists in the 1990s and early 2000s rediscovering early psychedelic studies and realizing the field to which they’d devoted their professional lives had a fascinating secret history. Before long, these taboo substances once again seemed less a malign narcotic than a potentially powerful medication.

As is to be expected of a nonfiction writer of his caliber, Pollan makes the story of the rise and fall and rise of psychedelic drug research gripping and surprising. He also reminds readers that excitement around any purportedly groundbreaking substance tends to dim as studies widen. In the early 1980s, for instance, SSRI antidepressants were hailed as the answer to human melancholy; these days, most perform only slightly better than a placebo.

Michael pollan how to change your mind

ALSO BY Michael Pollan

In Defense of Food

The Omnivore’s Dilemma

The Botany of Desire

A Place of My Own

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

Copyright © 2018 by Michael Pollan

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Image here and here from “Homological scaffolds of brain functional networks,” by G. Petri, P. Expert, F. Turkheimer, R. Carhart-Harris, D. Nutt, P. J. Hellyer, and F. Vaccarino, Journal of the Royal Society Interface, 2014.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Pollan, Michael, 1955– author.

Title: How to change your mind : what the new science of psychedelics teaches us about consciousness, dying, addiction, depression, and transcendence / Michael Pollan.

Description: New York : Penguin Press, 2018.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018006190 (print) | LCCN 2018010396 (ebook) | ISBN 9780525558941 (ebook) | ISBN 9781594204227 (hardback)

Subjects: LCSH: Pollan, Michael, 1955—Mental health. | Hallucinogenic drugs—Therapeutic use. | Psychotherapy patients—Biography. | BISAC: BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Science & Technology. | MEDICAL / Mental Health.

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018006190

NOTE: This book relates the author’s investigative reporting on, and related self-experimentation with, psilocybin mushrooms, the drug lysergic acid diethylamide (or, as it is more commonly known, LSD), and the drug 5-methoxy-N,N-dimethyltryptamine (more commonly known as 5-MeO-DMT or The Toad). It is a criminal offense in the United States and in many other countries, punishable by imprisonment and/or fines, to manufacture, possess, or supply LSD, psilocybin mushrooms, and/or the drug 5-MeO-DMT, except in connection with government-sanctioned research. You should therefore understand that this book is intended to convey the author’s experiences and to provide an understanding of the background and current state of research into these substances. It is not intended to encourage you to break the law and no attempt should be made to use these substances for any purpose except in a legally sanctioned clinical trial. The author and the publisher expressly disclaim any liability, loss, or risk, personal or otherwise, that is incurred as a consequence, directly or indirectly, of the contents of this book.

Certain names and locations have been changed in order to protect the author and others.

The soul should always stand ajar.

Also by Michael Pollan

Prologue: A New Door

Natural History: Bemushroomed

History: The First Wave

Part I: The Promise

Part II: The Crack-Up

Travelogue: Journeying Underground

Trip Two: Psilocybin

Trip Three: 5-MeO-DMT (or, The Toad)

The Neuroscience: Your Brain on Psychedelics

The Trip Treatment: Psychedelics in Psychotherapy

Coda: Going to Meet My Default Mode Network

Epilogue: In Praise of Neural Diversity

About the Author

MIDWAY THROUGH the twentieth century, two unusual new molecules, organic compounds with a striking family resemblance, exploded upon the West. In time, they would change the course of social, political, and cultural history, as well as the personal histories of the millions of people who would eventually introduce them to their brains. As it happened, the arrival of these disruptive chemistries coincided with another world historical explosion—that of the atomic bomb. There were people who compared the two events and made much of the cosmic synchronicity. Extraordinary new energies had been loosed upon the world; things would never be quite the same.

The first of these molecules was an accidental invention of science. Lysergic acid diethylamide, commonly known as LSD, was first synthesized by Albert Hofmann in 1938, shortly before physicists split an atom of uranium for the first time. Hofmann, who worked for the Swiss pharmaceutical firm Sandoz, had been looking for a drug to stimulate circulation, not a psychoactive compound. It wasn’t until five years later when he accidentally ingested a minuscule quantity of the new chemical that he realized he had created something powerful, at once terrifying and wondrous.

The second molecule had been around for thousands of years, though no one in the developed world was aware of it. Produced not by a chemist but by an inconspicuous little brown mushroom, this molecule, which would come to be known as psilocybin, had been used by the indigenous peoples of Mexico and Central America for hundreds of years as a sacrament. Called teonanácatl by the Aztecs, or “flesh of the gods,” the mushroom was brutally suppressed by the Roman Catholic Church after the Spanish conquest and driven underground. In 1955, twelve years after Albert Hofmann’s discovery of LSD, a Manhattan banker and amateur mycologist named R. Gordon Wasson sampled the magic mushroom in the town of Huautla de Jiménez in the southern Mexican state of Oaxaca. Two years later, he published a fifteen-page account of the “mushrooms that cause strange visions” in Life magazine, marking the moment when news of a new form of consciousness first reached the general public. (In 1957, knowledge of LSD was mostly confined to the community of researchers and mental health professionals.) People would not realize the magnitude of what had happened for several more years, but history in the West had shifted.

The impact of these two molecules is hard to overestimate. The advent of LSD can be linked to the revolution in brain science that begins in the 1950s, when scientists discovered the role of neurotransmitters in the brain. That quantities of LSD measured in micrograms could produce symptoms resembling psychosis inspired brain scientists to search for the neurochemical basis of mental disorders previously believed to be psychological in origin. At the same time, psychedelics found their way into psychotherapy, where they were used to treat a variety of disorders, including alcoholism, anxiety, and depression. For most of the 1950s and early 1960s, many in the psychiatric establishment regarded LSD and psilocybin as miracle drugs.

The arrival of these two compounds is also linked to the rise of the counterculture during the 1960s and, perhaps especially, to its particular tone and style. For the first time in history,

the young had a rite of passage all their own: the “acid trip.” Instead of folding the young into the adult world, as rites of passage have always done, this one landed them in a country of the mind few adults had any idea even existed. The effect on society was, to put it mildly, disruptive.

Yet by the end of the 1960s, the social and political shock waves unleashed by these molecules seemed to dissipate. The dark side of psychedelics began to receive tremendous amounts of publicity—bad trips, psychotic breaks, flashbacks, suicides—and beginning in 1965 the exuberance surrounding these new drugs gave way to moral panic. As quickly as the culture and the scientific establishment had embraced psychedelics, they now turned sharply against them. By the end of the decade, psychedelic drugs—which had been legal in most places—were outlawed and forced underground. At least one of the twentieth century’s two bombs appeared to have been defused.

Then something unexpected and telling happened. Beginning in the 1990s, well out of view of most of us, a small group of scientists, psychotherapists, and so-called psychonauts, believing that something precious had been lost from both science and culture, resolved to recover it.

Today, after several decades of suppression and neglect, psychedelics are having a renaissance. A new generation of scientists, many of them inspired by their own personal experience of the compounds, are testing their potential to heal mental illnesses such as depression, anxiety, trauma, and addiction. Other scientists are using psychedelics in conjunction with new brain-imaging tools to explore the links between brain and mind, hoping to unravel some of the mysteries of consciousness.

One good way to understand a complex system is to disturb it and then see what happens. By smashing atoms, a particle accelerator forces them to yield their secrets. By administering psychedelics in carefully calibrated doses, neuroscientists can profoundly disturb the normal waking consciousness of volunteers, dissolving the structures of the self and occasioning what can be described as a mystical experience. While this is happening, imaging tools can observe the changes in the brain’s activity and patterns of connection. Already this work is yielding surprising insights into the “neural correlates” of the sense of self and spiritual experience. The hoary 1960s platitude that psychedelics offered a key to understanding—and “expanding”—consciousness no longer looks quite so preposterous.

How to Change Your Mind is the story of this renaissance. Although it didn’t start out that way, it is a very personal as well as public history. Perhaps this was inevitable. Everything I was learning about the third-person history of psychedelic research made me want to explore this novel landscape of the mind in the first person too—to see how the changes in consciousness these molecules wrought actually feel and what, if anything, they had to teach me about my mind and might contribute to my life.

THIS WAS, FOR ME, a completely unexpected turn of events. The history of psychedelics I’ve summarized here is not a history I lived. I was born in 1955, halfway through the decade that psychedelics first burst onto the American scene, but it wasn’t until the prospect of turning sixty had drifted into view that I seriously considered trying LSD for the first time. Coming from a baby boomer, that might sound improbable, a dereliction of generational duty. But I was only twelve years old in 1967, too young to have been more than dimly aware of the Summer of Love or the San Francisco Acid Tests. At fourteen, the only way I was going to get to Woodstock was if my parents drove me. Much of the 1960s I experienced through the pages of Time magazine. By the time the idea of trying or not trying LSD swam into my conscious awareness, it had already completed its speedy media arc from psychiatric wonder drug to counterculture sacrament to destroyer of young minds.

I must have been in junior high school when a scientist reported (mistakenly, as it turned out) that LSD scrambled your chromosomes; the entire media, as well as my health-ed teacher, made sure we heard all about it. A couple of years later, the television personality Art Linkletter began campaigning against LSD, which he blamed for the fact his daughter had jumped out of an apartment window, killing herself. LSD supposedly had something to do with the Manson murders too. By the early 1970s, when I went to college, everything you heard about LSD seemed calculated to terrify. It worked on me: I’m less a child of the psychedelic 1960s than of the moral panic that psychedelics provoked.

I also had my own personal reason for steering clear of psychedelics: a painfully anxious adolescence that left me (and at least one psychiatrist) doubting my grip on sanity. By the time I got to college, I was feeling sturdier, but the idea of rolling the mental dice with a psychedelic drug still seemed like a bad idea.

Years later, in my late twenties and feeling more settled, I did try magic mushrooms two or three times. A friend had given me a Mason jar full of dried, gnarly Psilocybes, and on a couple of memorable occasions my partner (now wife), Judith, and I choked down two or three of them, endured a brief wave of nausea, and then sailed off on four or five interesting hours in the company of each other and what felt like a wonderfully italicized version of the familiar reality.

Psychedelic aficionados would probably categorize what we had as a low-dose “aesthetic experience,” rather than a full-blown ego-disintegrating trip. We certainly didn’t take leave of the known universe or have what anyone would call a mystical experience. But it was really interesting. What I particularly remember was the preternatural vividness of the greens in the woods, and in particular the velvety chartreuse softness of the ferns. I was gripped by a powerful compulsion to be outdoors, undressed, and as far from anything made of metal or plastic as it was possible to get. Because we were alone in the country, this was all doable. I don’t recall much about a follow-up trip on a Saturday in Riverside Park in Manhattan except that it was considerably less enjoyable and unselfconscious, with too much time spent wondering if other people could tell that we were high.

I didn’t know it at the time, but the difference between these two experiences of the same drug demonstrated something important, and special, about psychedelics: the critical influence of “set” and “setting.” Set is the mind-set or expectation one brings to the experience, and setting is the environment in which it takes place. Compared with other drugs, psychedelics seldom affect people the same way twice, because they tend to magnify whatever’s already going on both inside and outside one’s head.

After those two brief trips, the mushroom jar lived in the back of our pantry for years, untouched. The thought of giving over a whole day to a psychedelic experience had come to seem inconceivable. We were working long hours at new careers, and those vast swaths of unallocated time that college (or unemployment) affords had become a memory. Now another, very different kind of drug was available, one that was considerably easier to weave into the fabric of a Manhattan career: cocaine. The snowy-white powder made the wrinkled brown mushrooms seem dowdy, unpredictable, and overly demanding. Cleaning out the kitchen cabinets one weekend, we stumbled upon the forgotten jar and tossed it in the trash, along with the exhausted spices and expired packages of food.

Fast-forward three decades, and I really wish I hadn’t done that. I’d give a lot to have a whole jar of magic mushrooms now. I’ve begun to wonder if perhaps these remarkable molecules might be wasted on the young, that they may have more to offer us later in life, after the cement of our mental habits and everyday behaviors has set. Carl Jung once wrote that it is not the young but people in middle age who need to have an “experience of the numinous” to help them negotiate the second half of their lives.

By the time I arrived safely in my fifties, life seemed to be running along a few deep but comfortable grooves: a long and happy marriage alongside an equally long and gratifying career. As we do, I had developed a set of fairly dependable mental algorithms for navigating whatever life threw at me, whether at home or at work. What was missing from my life? Nothing I could think of—until, that is, word of th

e new research into psychedelics began to find its way to me, making me wonder if perhaps I had failed to recognize the potential of these molecules as a tool for both understanding the mind and, potentially, changing it.

HERE ARE THE THREE DATA POINTS that persuaded me this was the case.

In the spring of 2010, a front-page story appeared in the New York Times headlined “Hallucinogens Have Doctors Tuning In Again.” It reported that researchers had been giving large doses of psilocybin—the active compound in magic mushrooms—to terminal cancer patients as a way to help them deal with their “existential distress” at the approach of death.

These experiments, which were taking place simultaneously at Johns Hopkins, UCLA, and New York University, seemed not just improbable but crazy. Faced with a terminal diagnosis, the very last thing I would want to do is take a psychedelic drug—that is, surrender control of my mind and then in that psychologically vulnerable state stare straight into the abyss. But many of the volunteers reported that over the course of a single guided psychedelic “journey” they reconceived how they viewed their cancer and the prospect of dying. Several of them said they had lost their fear of death completely. The reasons offered for this transformation were intriguing but also somewhat elusive. “Individuals transcend their primary identification with their bodies and experience ego-free states,” one of the researchers was quoted as saying. They “return with a new perspective and profound acceptance.”

I filed that story away, until a year or two later, when Judith and I found ourselves at a dinner party at a big house in the Berkeley Hills, seated at a long table with a dozen or so people, when a woman at the far end of the table began talking about her acid trips. She looked to be about my age and, I learned, was a prominent psychologist. I was engrossed in a different conversation at the time, but as soon as the phonemes L-S-D drifted down to my end of the table, I couldn’t help but cup my ear (literally) and try to tune in.

Michael Pollan: How to Change Your Mind

Midway through the twentieth century, two unusual new molecules, organic compounds with a striking family resemblance, exploded upon the West. In time, they would change the course of social, political, and cultural history, as well as the personal histories of the millions of people who would eventually introduce them to their brains. As it happened, the arrival of these disruptive chemistries coincided with another world historical explosion — that of the atomic bomb. There were people who compared the two events and made much of the cosmic synchronicity. Extraordinary new energies had been loosed upon the world; things would never be quite the same.

The first of these molecules was an accidental invention of science. Lysergic acid diethylamide, commonly known as LSD, was first synthesized by Albert Hofmann in 1938, shortly before physicists split an atom of uranium for the first time. Hofmann, who worked for the Swiss pharmaceutical firm Sandoz, had been looking for a drug to stimulate circulation, not a psychoactive compound. It wasn’t until five years later when he accidentally ingested a minuscule quantity of the new chemical that he realized he had created something powerful, at once terrifying and wondrous.

The second molecule had been around for thousands of years, though no one in the developed world was aware of it. Produced not by a chemist but by an inconspicuous little brown mushroom, this molecule, which would come to be known as psilocybin, had been used by the indigenous peoples of Mexico and Central America for hundreds of years as a sacrament. Called teonanácatl by the Aztecs, or “flesh of the gods,” the mushroom was brutally suppressed by the Roman Catholic Church after the Spanish conquest and driven underground. In 1955, t

welve years after Albert Hofmann’s discovery of LSD, a Manhattan banker and amateur mycologist named R. Gordon Wasson sampled the magic mushroom in the town of Huautla de Jiménez in the southern Mexican state of Oaxaca. Two years later, he published a fifteen-page account of the “mushrooms that cause strange visions” in Life magazine, marking the moment when news of a new form of consciousness first reached the general public. (In 1957, knowledge of LSD was mostly confined to the community of researchers and mental health professionals.) People would not realize the magnitude of what had happened for several more years, but history in the West had shifted.

The impact of these two molecules is hard to overestimate. The advent of LSD can be linked to the revolution in brain science that begins in the 1950s, when scientists discovered the role of neurotransmitters in the brain. That quantities of LSD measured in micrograms could produce symptoms resembling psychosis inspired brain scientists to search for the neurochemical basis of mental disorders previously believed to be psychological in origin. At the same time, psychedelics found their way into psychotherapy, where they were used to treat a variety of disorders, including alcoholism, anxiety, and depression. For most of the 1950s and early 1960s, many in the psychiatric establishment regarded LSD and psilocybin as miracle drugs.

The arrival of these two compounds is also linked to the rise of the counterculture during the 1960s and, perhaps especially, to its particular tone and style. For the first time in history, the young had a rite of passage all their own: the “acid trip.” Instead of folding the young into the adult world, as rites of passage have always done, this one landed them in a country of the mind few adults had any idea even existed. The effect on society was, to put it mildly, disruptive.

Yet by the end of the 1960s, the social and political shock waves unleashed by these molecules seemed to dissipate. The dark side of psychedelics began to receive tremendous amounts of publicity — bad trips, psychotic breaks, flashbacks, suicides — and beginning in 1965 the exuberance surrounding these new drugs gave way to moral panic. As quickly as the culture and the scientific establishment had embraced psychedelics, they now turned sharply against them. By the end of the decade, psychedelic drugs — which had been legal in most places — were outlawed and forced underground. At least one of the twentieth century’s two bombs appeared to have been defused.

Michael Pollan will be speaking about the fascinating research into psychedelics behind How to Change Your Mind at the upcoming Bioneers conference in October 2018. Get your tickets today.

Then something unexpected and telling happened. Beginning in the 1990s, well out of view of most of us, a small group of scientists, psychotherapists, and so-called psychonauts, believing that something precious had been lost from both science and culture, resolved to recover it.

Today, after several decades of suppression and neglect, psychedelics are having a renaissance. A new generation of scientists, many of them inspired by their own personal experience of the compounds, are testing their potential to heal mental illnesses such as depression, anxiety, trauma, and addiction. Other scientists are using psychedelics in conjunction with new brain-imaging tools to explore the links between brain and mind, hoping to unravel some of the mysteries of consciousness.

One good way to understand a complex system is to disturb it and then see what happens. By smashing atoms, a particle accelerator forces them to yield their secrets. By administering psychedelics in carefully calibrated doses, neuroscientists can profoundly disturb the normal waking consciousness of volunteers, dissolving the structures of the self and occasioning what can be described as a mystical experience. While this is happening, imaging tools can observe the changes in the brain’s activity and patterns of connection. Already this work is yielding surprising insights into the “neural correlates” of the sense of self and spiritual experience. The hoary 1960s platitude that psychedelics offered a key to understanding — and “expanding” — consciousness no longer looks quite so preposterous.

How to Change Your Mind is the story of this renaissance. Although it didn’t start out that way, it is a very personal as well as public history. Perhaps this was inevitable. Everything I was learning about the third-person history of psychedelic research made me want to explore this novel landscape of the mind in the first person too — to see how the changes in consciousness these molecules wrought actually feel and what, if anything, they had to teach me about my mind and might contribute to my life.

This was, for me, a completely unexpected turn of events. The history of psychedelics I’ve summarized here is not a history I lived. I was born in 1955, halfway through the decade that psychedelics first burst onto the American scene, but it wasn’t until the prospect of turning sixty had drifted into view that I seriously considered trying LSD for the first time. Coming from a baby boomer, that might sound improbable, a dereliction of generational duty. But I was only twelve years old in 1967, too young to have been more than dimly aware of the Summer of Love or the San Francisco Acid Tests. At fourteen, the only way I was going to get to Woodstock was if my parents drove me. Much of the 1960s I experienced through the pages of Time magazine. By the time the idea of trying or not trying LSD swam into my conscious awareness, it had already completed its speedy media arc from psychiatric wonder drug to counterculture sacrament to destroyer of young minds.

I must have been in junior high school when a scientist reported (mistakenly, as it turned out) that LSD scrambled your chromosomes; the entire media, as well as my health-ed teacher, made sure we heard all about it. A couple of years later, the television personality Art Linkletter began campaigning against LSD, which he blamed for the fact his daughter had jumped out of an apartment window, killing herself. LSD supposedly had something to do with the Manson murders too. By the early 1970s, when I went to college, everything you heard about LSD seemed calculated to terrify. It worked on me: I’m less a child of the psychedelic 1960s than of the moral panic that psychedelics provoked.

I also had my own personal reason for steering clear of psychedelics: a painfully anxious adolescence that left me (and at least one psychiatrist) doubting my grip on sanity. By the time I got to college, I was feeling sturdier, but the idea of rolling the mental dice with a psychedelic drug still seemed like a bad idea.

Years later, in my late twenties and feeling more settled, I did try magic mushrooms two or three times. A friend had given me a Mason jar full of dried, gnarly Psilocybes, and on a couple of memorable occasions my partner (now wife), Judith, and I choked down two or three of them, endured a brief wave of nausea, and then sailed off on four or five interesting hours in the company of each other and what felt like a wonderfully italicized version of the familiar reality.

Psychedelic aficionados would probably categorize what we had as a low-dose “aesthetic experience,” rather than a full-blown ego-disintegrating trip. We certainly didn’t take leave of the known universe or have what anyone would call a mystical experience. But it was really interesting. What I particularly remember was the preternatural vividness of the greens in the woods, and in particular the velvety chartreuse softness of the ferns. I was gripped by a powerful compulsion to be outdoors, undressed, and as far from anything made of metal or plastic as it was possible to get. Because we were alone in the country, this was all doable. I don’t recall much about a follow-up trip on a Saturday in Riverside Park in Manhattan except that it was considerably less enjoyable and unselfconscious, with too much time spent wondering if other people could tell that we were high.

I didn’t know it at the time, but the difference between these two experiences of the same drug demonstrated something important, and special, about psychedelics: the critical influence of “set” and “setting.” Set is the mind-set or expectation one brings to the experience, and setting is the environment in which it takes place. Compared with other drugs, psychedelics seldom affect people the same way twice, because they tend to magnify whatever’s already going on both inside and outside one’s head.

After those two brief trips, the mushroom jar lived in the back of our pantry for years, untouched. The thought of giving over a whole day to a psychedelic experience had come to seem inconceivable. We were working long hours at new careers, and those vast swaths of unallocated time that college (or unemployment) affords had become a memory. Now another, very different kind of drug was available, one that was considerably easier to weave into the fabric of a Manhattan career: cocaine. The snowy-white powder made the wrinkled brown mushrooms seem dowdy, unpredictable, and overly demanding. Cleaning out the kitchen cabinets one weekend, we stumbled upon the forgotten jar and tossed it in the trash, along with the exhausted spices and expired packages of food.

Fast-forward three decades, and I really wish I hadn’t done that. I’d give a lot to have a whole jar of magic mushrooms now. I’ve begun to wonder if perhaps these remarkable molecules might be wasted on the young, that they may have more to offer us later in life, after the cement of our mental habits and everyday behaviors has set. Carl Jung once wrote that it is not the young but people in middle age who need to have an “experience of the numinous” to help them negotiate the second half of their lives.

By the time I arrived safely in my fifties, life seemed to be running along a few deep but comfortable grooves: a long and happy marriage alongside an equally long and gratifying career. As we do, I had developed a set of fairly dependable mental algorithms for navigating whatever life threw at me, whether at home or at work. What was missing from my life? Nothing I could think of — until, that is, word of the new research into psychedelics began to find its way to me, making me wonder if perhaps I had failed to recognize the potential of these molecules as a tool for both understanding the mind and, potentially, changing it.

Here are the three data points that persuaded me this was the case.

In the spring of 2010, a front-page story appeared in the New York Times headlined “Hallucinogens Have Doctors Tuning In Again.” It reported that researchers had been giving large doses of psilocybin — the active compound in magic mushrooms — to terminal cancer patients as a way to help them deal with their “existential distress” at the approach of death.

These experiments, which were taking place simultaneously at Johns Hopkins, UCLA, and New York University, seemed not just improbable but crazy. Faced with a terminal diagnosis, the very last thing I would want to do is take a psychedelic drug — that is, surrender control of my mind and then in that psychologically vulnerable state stare straight into the abyss. But many of the volunteers reported that over the course of a single guided psychedelic “journey” they reconceived how they viewed their cancer and the prospect of dying. Several of them said they had lost their fear of death completely. The reasons offered for this transformation were intriguing but also somewhat elusive. “Individuals transcend their primary identification with their bodies and experience ego-free states,” one of the researchers was quoted as saying. They “return with a new perspective and profound acceptance.”

I filed that story away, until a year or two later, when Judith and I found ourselves at a dinner party at a big house in the Berkeley Hills, seated at a long table with a dozen or so people, when a woman at the far end of the table began talking about her acid trips. She looked to be about my age and, I learned, was a prominent psychologist. I was engrossed in a different conversation at the time, but as soon as the phonemes L-S-D drifted down to my end of the table, I couldn’t help but cup my ear (literally) and try to tune in.

At first, I assumed she was dredging up some well-polished anecdote from her college days. Not the case. It soon became clear that the acid trip in question had taken place only days or weeks before, and in fact was one of her first. The assembled eyebrows rose. She and her husband, a retired software engineer, had found the occasional use of LSD both intellectually stimulating and of value to their work. Specifically, the psychologist felt that LSD gave her insight into how young children perceive the world. Kids’ perceptions are not mediated by expectations and conventions in the been-there, done-that way that adult perception is; as adults, she explained, our minds don’t simply take in the world as it is so much as they make educated guesses about it. Relying on these guesses, which are based on past experience, saves the mind time and energy, as when, say, it’s trying to figure out what that fractal pattern of green dots in its visual field might be. (The leaves on a tree, probably.) LSD appears to disable such conventionalized, shorthand modes of perception and, by doing so, restores a childlike immediacy, and sense of wonder, to our experience of reality, as if we were seeing everything for the first time. ( Leaves!)

I piped up to ask if she had any plans to write about these ideas, which riveted everyone at the table. She laughed and gave me a look that I took to say, How naive can you be? LSD is a schedule 1 substance, meaning the government regards it as a drug of abuse with no accepted medical use. Surely it would be foolhardy for someone in her position to suggest, in print, that psychedelics might have anything to contribute to philosophy or psychology — that they might actually be a valuable tool for exploring the mysteries of human consciousness. Serious research into psychedelics had been more or less purged from the university fifty years ago, soon after Timothy Leary’s Harvard Psilocybin Project crashed and burned in 1963. Not even Berkeley, it seemed, was ready to go there again, at least not yet.

Third data point: The dinner table conversation jogged a vague memory that a few years before somebody had e-mailed me a scientific paper about psilocybin research. Busy with other things at the time, I hadn’t even opened it, but a quick search of the term “psilocybin” instantly fished the paper out of the virtual pile of discarded e-mail on my computer. The paper had been sent to me by one of its co-authors, a man I didn’t know by the name of Bob Jesse; perhaps he had read something I’d written about psychoactive plants and thought I might be interested. The article, which was written by the same team at Hopkins that was giving psilocybin to cancer patients, had just been published in the journal Psychopharmacology. For a peer-reviewed scientific paper, it had a most unusual title: “Psilocybin Can Occasion Mystical-Type Experiences Having Substantial and Sustained Personal Meaning and Spiritual Significance.”

Never mind the word “psilocybin”; it was the words “mystical” and “spiritual” and “meaning” that leaped out from the pages of a pharmacology journal. The title hinted at an intriguing frontier of research, one that seemed to straddle two worlds we’ve grown accustomed to think are irreconcilable: science and spirituality.

Now I fell on the Hopkins paper, fascinated. Thirty volunteers who had never before used psychedelics had been given a pill containing either a synthetic version of psilocybin or an “active placebo” — methylphenidate, or Ritalin — to fool them into thinking they had received the psychedelic. They then lay down on a couch wearing eyeshades and listening to music through headphones, attended the whole time by two therapists. (The eyeshades and headphones encourage a more inward-focused journey.) After about thirty minutes, extraordinary things began to happen in the minds of the people who had gotten the psilocybin pill.

The study demonstrated that a high dose of psilocybin could be used to safely and reliably “occasion” a mystical experience — typically described as the dissolution of one’s ego followed by a sense of merging with nature or the universe. This might not come as news to people who take psychedelic drugs or to the researchers who first studied them back in the 1950s and 1960s. But it wasn’t at all obvious to modern science, or to me, in 2006, when the paper was published.

What was most remarkable about the results reported in the article is that participants ranked their psilocybin experience as one of the most meaningful in their lives, comparable “to the birth of a first child or death of a parent.” Two-thirds of the participants rated the session among the top five “most spiritually significant experiences” of their lives; one-third ranked it the most significant such experience in their lives. Fourteen months later, these ratings had slipped only slightly. The volunteers reported significant improvements in their “personal well-being, life satisfaction and positive behavior change,” changes that were confirmed by their family members and friends.

Though no one knew it at the time, the renaissance of psychedelic research now under way began in earnest with the publication of that paper. It led directly to a series of trials — at Hopkins and several other universities — using psilocybin to treat a variety of indications, including anxiety and depression in cancer patients, addiction to nicotine and alcohol, obsessive-compulsive disorder, depression, and eating disorders. What is striking about this whole line of clinical research is the premise that it is not the pharmacological effect of the drug itself but the kind of mental experience it occasions — involving the temporary dissolution of one’s ego — that may be the key to changing one’s mind.

As someone not at all sure he has ever had a single “spiritually significant” experience, much less enough of them to make a ranking, I found that the 2006 paper piqued my curiosity but also my skepticism. Many of the volunteers described being given access to an alternative reality, a “beyond” where the usual physical laws don’t apply and various manifestations of cosmic consciousness or divinity present themselves as unmistakably real.

All this I found both a little hard to take (couldn’t this be just a drug-induced hallucination?) and yet at the same time intriguing; part of me wanted it to be true, whatever exactly “it” was. This surprised me, because I have never thought of myself as a particularly spiritual, much less mystical, person. This is partly a function of worldview, I suppose, and partly of neglect: I’ve never devoted much time to exploring spiritual paths and did not have a religious upbringing. My default perspective is that of the philosophical materialist, who believes that matter is the fundamental substance of the world and the physical laws it obeys should be able to explain everything that happens. I start from the assumption that nature is all that there is and gravitate toward scientific explanations of phenomena. That said, I’m also sensitive to the limitations of the scientific-materialist perspective and believe that nature (including the human mind) still holds deep mysteries toward which science can sometimes seem arrogant and unjustifiably dismissive.

Was it possible that a single psychedelic experience — something that turned on nothing more than the ingestion of a pill or square of blotter paper — could put a big dent in such a worldview? Shift how one thought about mortality? Actually change one’s mind in enduring ways?

The idea took hold of me. It was a little like being shown a door in a familiar room — the room of your own mind — that you had somehow never noticed before and being told by people you trusted (scientists!) that a whole other way of thinking — of being! — lay waiting on the other side. All you had to do was turn the knob and enter. Who wouldn’t be curious? I might not have been looking to change my life, but the idea of learning something new about it, and of shining a fresh light on this old world, began to occupy my thoughts. Maybe there was something missing from my life, something I just hadn’t named.

For our species, I learned, plants and fungi with the power to radically alter consciousness have long and widely been used as tools for healing the mind, for facilitating rites of passage, and for serving as a medium for communicating with supernatural realms, or spirit worlds. These uses were ancient and venerable in a great many cultures, but I ventured one other application: to enrich the collective imagination — the culture — with the novel ideas and visions that a select few people bring back from wherever it is they go.

Michael Pollan will be speaking about the fascinating research into psychedelics behind How to Change Your Mind at the upcoming Bioneers conference in October 2018. Get your tickets today.

Now that I had developed an intellectual appreciation for the potential value of these psychoactive substances, you might think I would have been more eager to try them. I’m not sure what I was waiting for: courage, maybe, or the right opportunity, which a busy life lived mainly on the right side of the law never quite seemed to afford. But when I began to weigh the potential benefits I was hearing about against the risks, I was surprised to learn that psychedelics are far more frightening to people than they are dangerous. Many of the most notorious perils are either exaggerated or mythical. It is virtually impossible to die from an overdose of LSD or psilocybin, for example, and neither drug is addictive. After trying them once, animals will not seek a second dose, and repeated use by people robs the drugs of their effect. It is true that the terrifying experiences some people have on psychedelics can risk flipping those at risk into psychosis, so no one with a family history or predisposition to mental illness should ever take them. But emergency room admissions involving psychedelics are exceedingly rare, and many of the cases doctors diagnose as psychotic breaks turn out to be merely short-lived panic attacks.

It is also the case that people on psychedelics are liable to do stupid and dangerous things: walk out into traffic, fall from high places, and, on rare occasions, kill themselves. “Bad trips” are very real and can be one of “the most challenging experiences of [a] lifetime,” according to a large survey of psychedelic users asked about their experiences. But it’s important to distinguish what can happen when these drugs are used in uncontrolled situations, without attention to set and setting, from what happens under clinical conditions, after careful screening and under supervision. Since the revival of sanctioned psychedelic research beginning in the 1990s, nearly a thousand volunteers have been dosed, and not a single serious adverse event has been reported.

It was at this point that the idea of “shaking the snow globe,” as one neuroscientist described the psychedelic experience, came to seem more attractive to me than frightening, though it was still that too.

After more than half a century of its more or less constant companionship, one’s self — this ever-present voice in the head, this ceaselessly commenting, interpreting, labeling, defending I — becomes perhaps a little too familiar. I’m not talking about anything as deep as self-knowledge here. No, just about how, over time, we tend to optimize and conventionalize our responses to whatever life brings. Each of us develops our shorthand ways of slotting and processing everyday experiences and solving problems, and while this is no doubt adaptive — it helps us get the job done with a minimum of fuss — eventually it becomes rote. It dulls us. The muscles of attention atrophy.

Habits are undeniably useful tools, relieving us of the need to run a complex mental operation every time we’re confronted with a new task or situation. Yet they also relieve us of the need to stay awake to the world: to attend, feel, think, and then act in a deliberate manner. (That is, from freedom rather than compulsion.) If you need to be reminded how completely mental habit blinds us to experience, just take a trip to an unfamiliar country. Suddenly you wake up! And the algorithms of everyday life all but start over, as if from scratch. This is why the various travel metaphors for the psychedelic experience are so apt.

The efficiencies of the adult mind, useful as they are, blind us to the present moment. We’re constantly jumping ahead to the next thing. We approach experience much as an artificial intelligence (AI) program does, with our brains continually translating the data of the present into the terms of the past, reaching back in time for the relevant experience, and then using that to make its best guess as to how to predict and navigate the future.

One of the things that commends travel, art, nature, work, and certain drugs to us is the way these experiences, at their best, block every mental path forward and back, immersing us in the flow of a present that is literally wonderful — wonder being the by-product of precisely the kind of unencumbered first sight, or virginal noticing, to which the adult brain has closed itself. (It’s so inefficient!) Alas, most of the time I inhabit a near-future tense, my psychic thermostat set to a low simmer of anticipation and, too often, worry. The good thing is I’m seldom surprised. The bad thing is I’m seldom surprised.

What I am struggling to describe here is what I think of as my default mode of consciousness. It works well enough, certainly gets the job done, but what if it isn’t the only, or necessarily the best, way to go through life? The premise of psychedelic research is that this special group of molecules can give us access to other modes of consciousness that might offer us specific benefits, whether therapeutic, spiritual, or creative. Psychedelics are certainly not the only door to these other forms of consciousness — and I explore some non-pharmacological alternatives in these pages — but they do seem to be one of the easier knobs to take hold of and turn.

The whole idea of expanding our repertoire of conscious states is not an entirely new idea: Hinduism and Buddhism are steeped in it, and there are intriguing precedents even in Western science. William James, the pioneering American psychologist and author of The Varieties of Religious Experience, ventured into these realms more than a century ago. He returned with the conviction that our everyday waking consciousness “is but one special type of consciousness, whilst all about it, parted from it by the filmiest of screens, there lie potential forms of consciousness entirely different.”

James is speaking, I realized, of the unopened door in our minds. For him, the “touch” that could throw open the door and disclose these realms on the other side was nitrous oxide. (Mescaline, the psychedelic compound derived from the peyote cactus, was available to researchers at the time, but James was apparently too fearful to try it.)

“No account of the universe in its totality can be final which leaves these other forms of consciousness quite disregarded.

“At any rate,” James concluded, these other states, the existence of which he believed was as real as the ink on this page, “forbid a premature closing of our accounts with reality.”

The first time I read that sentence, I realized James had my number: as a staunch materialist, and as an adult of a certain age, I had pretty much closed my accounts with reality. Perhaps this had been premature.

Well, here was an invitation to reopen them.

If everyday waking consciousness is but one of several possible ways to construct a world, then perhaps there is value in cultivating a greater amount of what I’ve come to think of as neural diversity. With that in mind, How to Change Your Mind approaches its subject from several different perspectives, employing several different narrative modes: social and scientific history; natural history; memoir; science journalism; and case studies of volunteers and patients. In the middle of the journey, I also offer an account of my own firsthand research (or perhaps I should say search) in the form of a kind of mental travelogue.

In telling the story of psychedelic research, past and present, I do not attempt to be comprehensive. The subject of psychedelics, as a matter of both science and social history, is too vast to squeeze between the covers of a single book. Rather than try to introduce readers to the entire cast of characters responsible for the psychedelic renaissance, my narrative follows a small number of pioneers who constitute a particular scientific lineage, with the inevitable result that the contributions of many others have received short shrift. Also in the interest of narrative coherence, I’ve focused on certain drugs to the exclusion of others. There is, for example, little here about MDMA (also known as Ecstasy), which is showing great promise in the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder. Some researchers count MDMA among the psychedelics, but most do not, and I follow their lead. MDMA operates through a different set of pathways in the brain and has a substantially different social history from that of the so-called classical psychedelics. Of these, I focus primarily on the ones that are receiving the most attention from scientists — psilocybin and LSD — which means that other psychedelics that are equally interesting and powerful but more difficult to bring into the laboratory — such as ayahuasca — receive less attention.

A final word on nomenclature. The class of molecules to which psilocybin and LSD (and mescaline, DMT, and a handful of others) belong has been called by many names in the decades since they have come to our attention. Initially, they were called hallucinogens. But they do so many other things (and in fact full-blown hallucinations are fairly uncommon) that researchers soon went looking for more precise and comprehensive terms, a quest chronicled in chapter three. The term “psychedelics,” which I will mainly use here, does have its downside. Embraced in the 1960s, the term carries a lot of countercultural baggage. Hoping to escape those associations and underscore the spiritual dimensions of these drugs, some researchers have proposed they instead be called “entheogens” — from the Greek for “the divine within.” This strikes me as too emphatic. Despite the 1960s trappings, the term “psychedelic,” coined in 1956, is etymologically accurate. Drawn from the Greek, it means simply “mind manifesting,” which is precisely what these extraordinary molecules hold the power to do.

This excerpt has been reprinted with permission from How to Change Your Mind by Michael Pollan, published by Penguin Press, 2018.

Archives

surprise me

ABOUT

CONTACT

SUPPORT

SUBSCRIBE

CONNECT

Sunday newsletter

The Marginalian has a free Sunday digest of the week’s most mind-broadening and heart-lifting reflections spanning art, science, poetry, philosophy, and other tendrils of our search for truth, beauty, meaning, and creative vitality. Here’s an example. Like? Claim yours:

midweek newsletter

Also: Because The Marginalian is well into its second decade and because I write primarily about ideas of timeless nourishment, each Wednesday I dive into the archive and resurface from among the thousands of essays one worth resavoring. Subscribe to this free midweek pick-me-up for heart, mind, and spirit below — it is separate from the standard Sunday digest of new pieces:

The Universe in Verse

Figuring

The Snail with the Right Heart: A True Story

A Velocity of Being

sounds

bites

bookshelf

Favorite Reads

Becoming the Marginalian: After 15 Years, Brain Pickings Reborn

Bloom: The Evolution of Life on Earth and the Birth of Ecology (Joan As Police Woman Sings Emily Dickinson)

Trial, Triumph, and the Art of the Possible: The Remarkable Story Behind Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy”

Resolutions for a Life Worth Living: Attainable Aspirations Inspired by Great Humans of the Past

Essential Life-Learnings from 14 Years of Brain Pickings

Emily Dickinson’s Electric Love Letters to Susan Gilbert

Singularity: Marie Howe’s Ode to Stephen Hawking, Our Cosmic Belonging, and the Meaning of Home, in a Stunning Animated Short Film

How Kepler Invented Science Fiction and Defended His Mother in a Witchcraft Trial While Revolutionizing Our Understanding of the Universe

Hannah Arendt on Love and How to Live with the Fundamental Fear of Loss

The Cosmic Miracle of Trees: Astronaut Leland Melvin Reads Pablo Neruda’s Love Letter to Earth’s Forests

Rebecca Solnit’s Lovely Letter to Children About How Books Solace, Empower, and Transform Us

Fixed vs. Growth: The Two Basic Mindsets That Shape Our Lives

In Praise of the Telescopic Perspective: A Reflection on Living Through Turbulent Times

A Stoic’s Key to Peace of Mind: Seneca on the Antidote to Anxiety

The Courage to Be Yourself: E.E. Cummings on Art, Life, and Being Unafraid to Feel

The Writing of “Silent Spring”: Rachel Carson and the Culture-Shifting Courage to Speak Inconvenient Truth to Power

A Rap on Race: Margaret Mead and James Baldwin’s Rare Conversation on Forgiveness and the Difference Between Guilt and Responsibility

The Science of Stress and How Our Emotions Affect Our Susceptibility to Burnout and Disease

Mary Oliver on What Attention Really Means and Her Moving Elegy for Her Soul Mate

Rebecca Solnit on Hope in Dark Times, Resisting the Defeatism of Easy Despair, and What Victory Really Means for Movements of Social Change

see more

Related Reads

Catching the Light of the World: The Entwined History of Vision and Consciousness

I Feel, Therefore I Am: Neuroscientist Antonio Damasio on Consciousness as a Full-Body Phenomenon

Favorite Books of 2018

Labors of Love

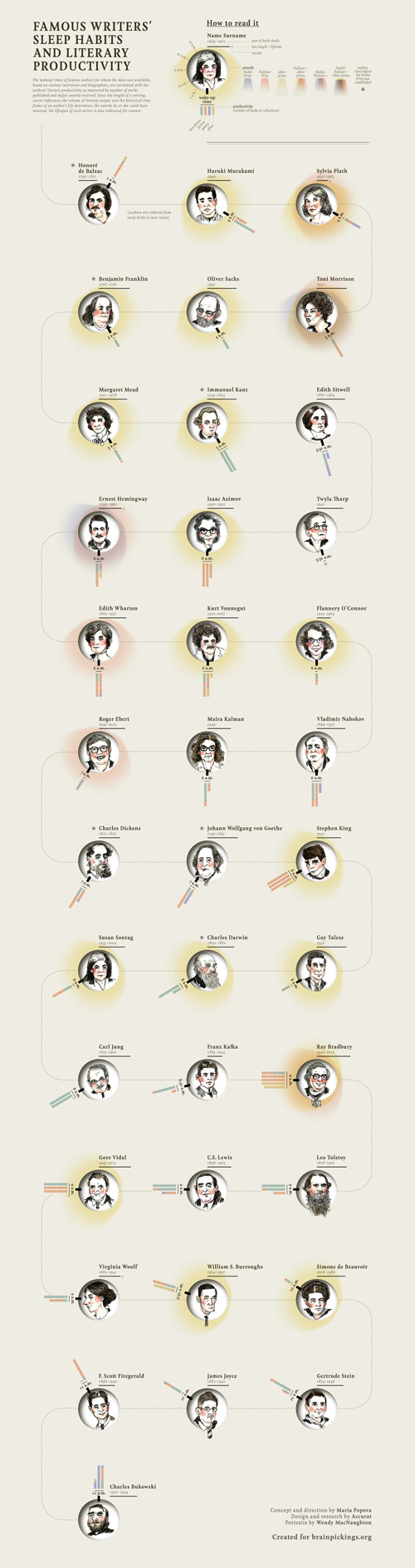

Famous Writers’ Sleep Habits vs. Literary Productivity, Visualized

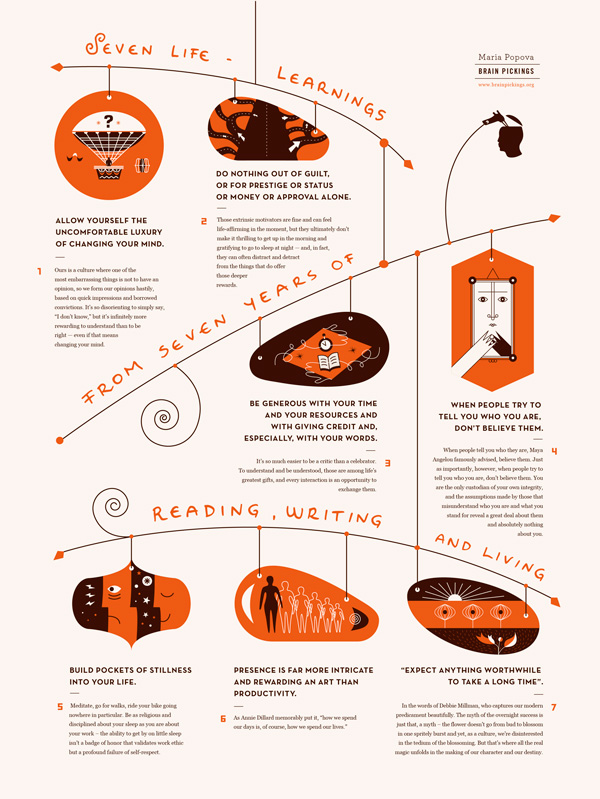

7 Life-Learnings from 7 Years of Brain Pickings, Illustrated

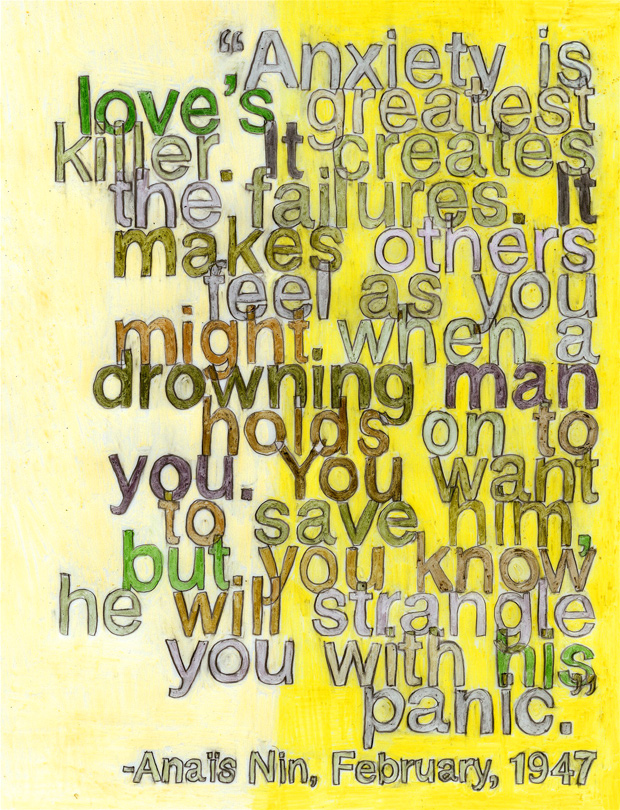

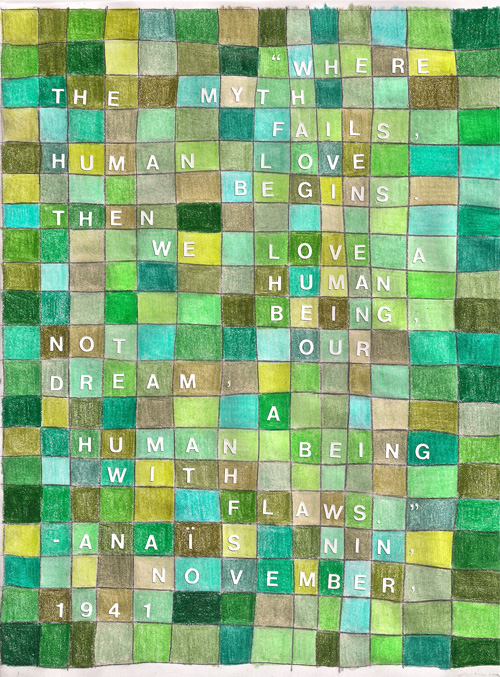

Anaïs Nin on Love, Hand-Lettered by Debbie Millman

Anaïs Nin on Real Love, Illustrated by Debbie Millman

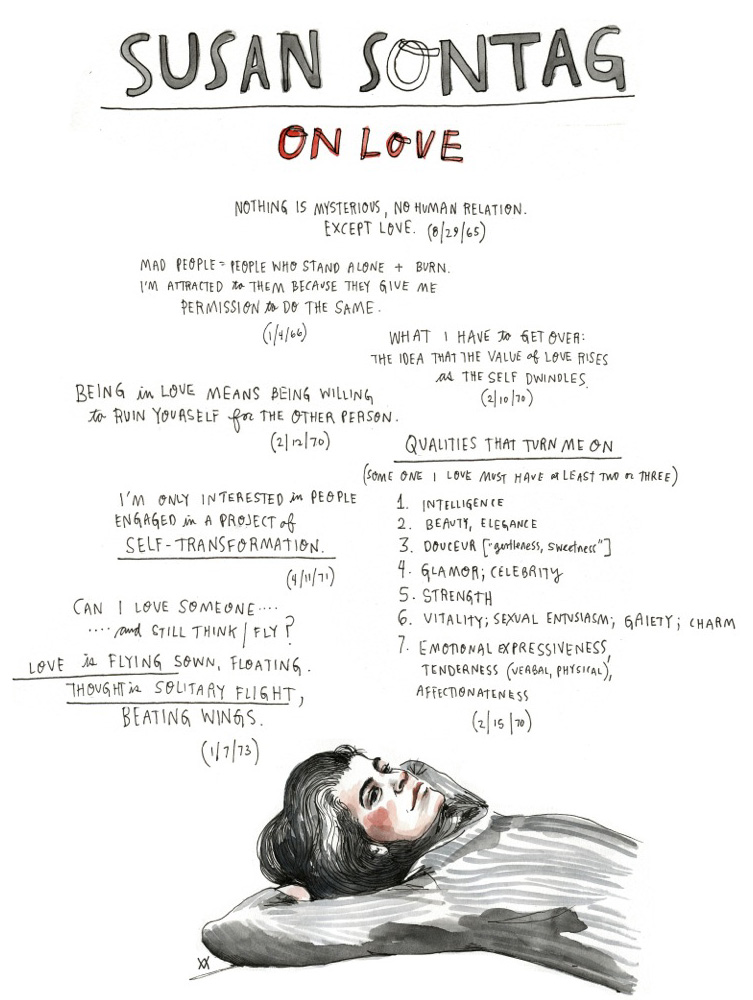

Susan Sontag on Love: Illustrated Diary Excerpts

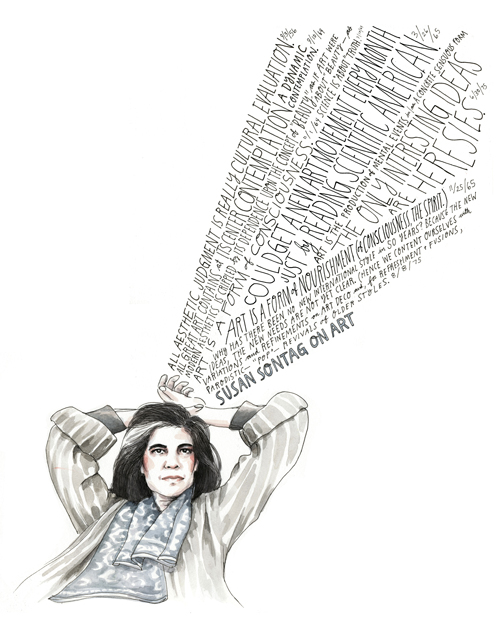

Susan Sontag on Art: Illustrated Diary Excerpts

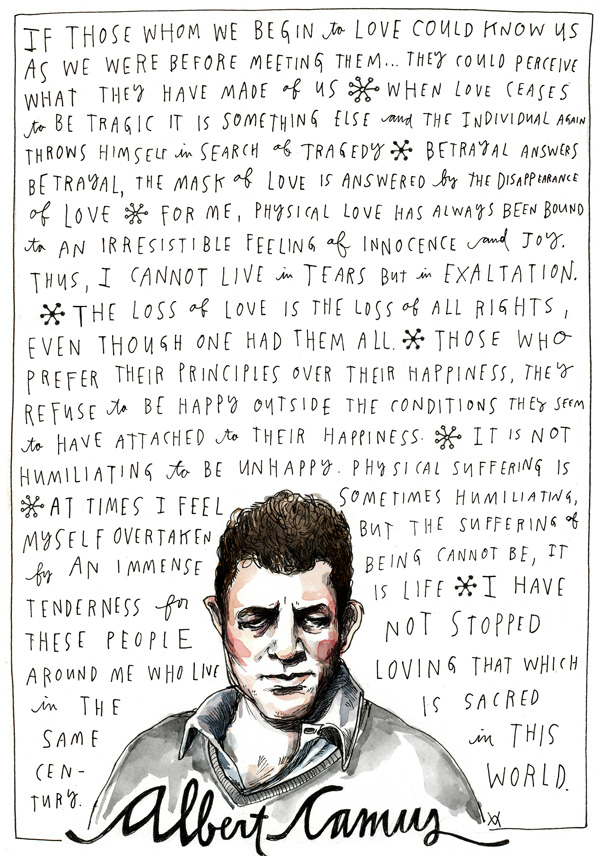

Albert Camus on Happiness and Love, Illustrated by Wendy MacNaughton

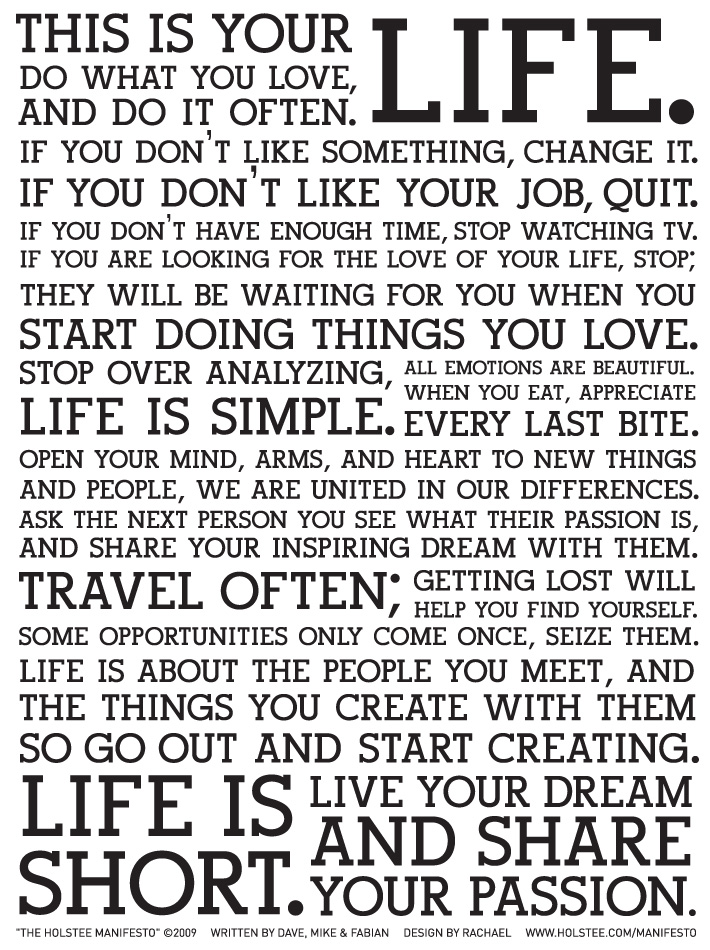

The Holstee Manifesto

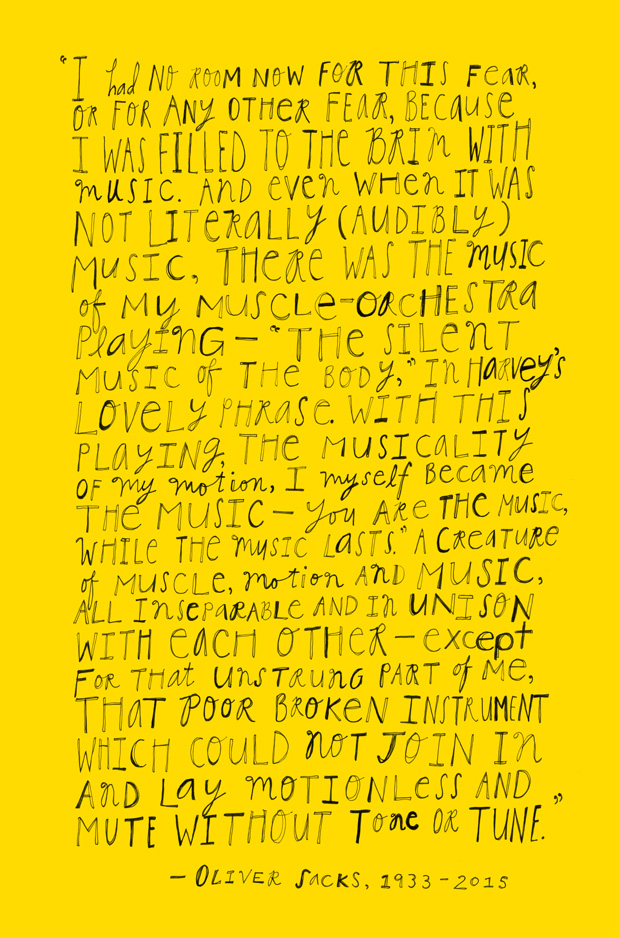

The Silent Music of the Mind: Remembering Oliver Sacks

How to Change Your Mind: Michael Pollan on How the Science of Psychedelics Illuminates Consciousness, Mortality, Addiction, Depression, and Transcendence

“The Beyond, whatever it consists of, might not be nearly as far away or inaccessible as we think.”

By Maria Popova

“Attention is an intentional, unapologetic discriminator. It asks what is relevant right now, and gears us up to notice only that,” cognitive scientist Alexandra Horowitz wrote in her inquiry into how our conditioned way of looking narrows the lens of our perception. Attention, after all, is the handmaiden of consciousness, and consciousness the central fact and the central mystery of our creaturely experience. From the days of Plato’s cave to the birth of neuroscience, we have endeavored to fathom its nature. But it is a mystery that only seems to deepen with each increment of approach. “Our normal waking consciousness,” William James wrote in his landmark 1902 treatise on spirituality, “is but one special type of consciousness, whilst all about it, parted from it by the filmiest of screens, there lie potential forms of consciousness entirely different… No account of the universe in its totality can be final which leaves these other forms of consciousness quite disregarded.”