What is consciousness and how does it relate to the brain

What is consciousness and how does it relate to the brain

What is Consciousness?

From the Material Brain to the Infinite Mind and Beyond

BY ERVIN LASZLO

A New Concept of Consciousness

W hat is consciousness? What about the mind? If the world is vibration, is also mind and consciousness a form of vibration? Or on the contrary, are all vibrations, the observed world, a manifestation of mind and human consciousness?

Although it is true that when all is said and done all we know is our consciousness, it is also true that we do not know our own consciousness, not to mention the consciousness of anyone else.

Both of these possibilities have been explored in the history of philosophy, and today we are a step closer than before to understanding which of these theories of consciousness is true. There are important insights emerging at the expanding frontiers where physical science and consciousness research join.

On the basis of a growing series of observations and experiments to answer the question of “What is consciousness?”, a new consensus is emerging. It is that “my” consciousness is not just my consciousness, meaning the consciousness produced by my brain, any more than a program transmitted over the air would be a program produced by my TV set. Just like a program broadcast over the air continues to exist when my TV set is turned off, my human consciousness and conscious awareness continues to exist when my brain is turned off.

Consciousness is a real element in the real world. The body and brain do not produce consciousness; they display it. And it does not cease when life in the body does. Mind and consciousness is a reflection, a projection, a manifestation of the intelligence that “in-forms” the world.

From the Material to the Infinite

Mystics and shamans have known that this is true for millennia, and artists and spiritual people know it to this day. Its rediscovery at the leading edge of the science of consciousness augurs a profound shift in our view of the world. It overcomes the answer the now outdated materialist science gives to the question regarding the nature of mind and consciousness: the answer according to which consciousness is an epiphenomenon, a product or by-product of the workings of the brain.

Free Enlightened Living Course: Take Your Happiness, Health, Prosperity & Consciousness to the Next Level

On first sight, this makes good sense. On a second look, however, the materialist concept of what is consciousness encounters major problems. First, a conceptual problem. How could a material brain give rise to a truly immaterial stream of sensations? How could anything that is material produce anything immaterial? In modern consciousness research and science this is known as the “hard problem.” It has no reasonable answer. As researchers point out, we do not have the slightest idea how “matter” could produce “mind.” One is a measurable entity with properties such as hardness, extension, force, and the like, and the other is an ineffable series of sensations with no definite location in space and an ephemeral presence in time.

Fortunately, the hard problem does not need to be solved: it is not a real problem. There is another possibility: mind is a real element in the real world and is not produced by the brain; it is manifested and displayed by the brain.

Mind beyond Brain: Evidence for a New Concept of Mind and Consciousness

If mind is a real element in the real world only manifested rather than produced by the brain, it can also exist without the brain. There is evidence that mind does exist on occasion beyond the brain: surprisingly, states of consciousness and conscious awareness seem possible in the absence of a functioning brain. There are cases—the near-death experience (NDE) is the paradigm case—where mind and consciousness persists when brain function is impaired, or even halted.

Thousands of observations and experiments show that people whose brain stopped working but then regained normal functioning can experience human consciousness during the time they are without a functioning brain. This cannot be accounted for on the premises of the production theory of consciousness: if there is no working brain, there cannot be consciousness. Yet there are cases of consciousness appearing beyond the living and working brain, and some of these cases are not easy to dismiss as mere imagination.

What Near Death Experiences Can Teach Us

A striking NDE was recounted by a young woman named Pamela. Hers has been just one among scores of NDEs that help to answer the question of what is consciousness; it is cited here to illustrate that such experiences exist, and can be documented.

Pamela died on May 29, 2010, at the age of fifty-three. But for hours she was effectively dead on the operating table nineteen years earlier. Her near demise was induced by a surgical team attempting to remove an aneurism in her brain stem.

After the operation, when her brain and body returned to normal functioning, Pamela described in detail what had taken place in the operating theater. She recalled among other things the music that was playing (“Hotel California” by the Eagles). She described a whole series of conversations among the medical team. She reported having watched the opening of her skull by the surgeon from a position above him and described in detail the “Midas Rex” bone-cutting device and the distinct sound it made.

About ninety minutes into the operation, at which point she should have had no brain function or conscious awareness, she saw her body from the outside and felt herself being pulled out of it and into a tunnel of light. And she heard the bone saw activate, even though there were specially designed speakers in each of her ears that shut out all external sounds. The speakers themselves were broadcasting audible clicks in order to confirm that there was no activity in her brain stem. Moreover, she had been given a general anesthetic that should have assured that she was fully unconscious. Pamela should not have been able either to see or to hear anything.

There are OBEs where congenitally blind people have visual awareness. They describe their surroundings in considerable detail and with remarkable accuracy. What the blind experience is not restored eyesight, because they are aware of things that are shielded from their eyes or are beyond the range of normal eyesight. Consciousness researcher Kenneth Ring called these states of consciousness “transcendental awareness.”

Visual awareness in the blind joins a growing repertory of experiences collected and researched by Stanislav Grof: “transcendental experiences.” As Grof, a pioneer in the science of consciousness and the mind, found, these beyond-the-brain and beyond-here-and-now experiences are widespread—more widespread than anyone would have suspected even a few years ago—and give us a clue into what consciousness is.

The Evidence of After Death Experiences

There are also reports of ADEs, after-death experiences that help expand on the question “What is Consciousness?” Thousands of psychic mediums claim to have channeled the conscious awareness and experience of deceased people, and some of these reports are not easy to dismiss as mere imagination. One of the most robust of these reports has come from Bertrand Russell, the renowned English philosopher. Lord Russell was a skeptic, an outspoken debunker of esoteric phenomena, including the survival of the mind or soul beyond the body. He once wrote, “I believe that when I die I shall rot, and nothing of my ego will survive.” Yet after he died he conveyed the following message to the medium Rosemary Brown.

You may not believe that it is I, Bertrand Arthur William Russell, who am saying these things, and perhaps there is no conclusive proof that I can offer through this somewhat restrictive medium. Those with an ear to hear may catch the echo of my voice in my phrases, the tenor of my tongue in my tautology; those who do not wish to hear will no doubt conjure up a whole table of tricks to disprove my retrospective rhetoric.

Several times in my life [Lord Russell continued] I had thought I was about to die; several times I had resigned myself with the best will that I could muster to ceasing to be. The idea of B.R. no longer inhabiting the world did not trouble me unduly. Befitting, I thought, to give the chap (myself) a decent burial and let him be. Now here I was, still the same I, with the capacities to think and observe sharpened to an incredible degree. I felt earth-life suddenly seemed very unreal almost as it had never happened. It took me quite a long while to understand that feeling until I realized at last that matter is certainly illusory although it does exist in actuality; the material world seemed now nothing more than a seething, changing, restless sea of indeterminable density and volume.

This report “from beyond” appears hardly credible, were it not that it is supported by other ADEs. One of the most striking and difficult to dismiss of these ADEs is the case of a deceased chess grand master who played a game with a living grand master.

Wolfgang Eisenbeiss, an amateur chess player, engaged the medium Robert Rollans to transmit the moves of a game to be played with Viktor Korchnoi, the world’s third-ranking grand master. His opponent was to be a player whom Rollans was to find in his trance state. Eisenbeiss gave Rollans a list of deceased grand masters and asked him to contact them and ask who would be willing to play. Rollans entered his state of trance and did so. On June 15, 1985, the former grand master Geza Maroczy responded and said that he was available. Maroczy was the third-ranking grand master in the year 1900. He was born in 1870 and died in 1951 at the age of eighty-one. Rollans reported that Maroczy responded to his invitation as follows.

I will be at your disposal in this peculiar game of chess for two reasons. First, because I also want to do something to aid mankind living on Earth to become convinced that death does not end everything, but instead the mind and consciousness is separated from the physical body and comes up to us in a new world, where individual life continues to manifest itself in a new unknown dimension. Second, being a Hungarian patriot, I want to guide the eyes of the world into the direction of my beloved Hungary.

Korchnoi and Maroczy began a game that was frequently interrupted due to Korchnoi’s poor health and numerous travels. It lasted seven years and eight months. Speaking through Robert Rollans, Maroczy gave his moves in the standard form: for example, “5. A3 – Bxc3+”; Korchnoi gave his own moves to Rollans in the same form, but by ordinary communication. Every move was analyzed and recorded. It turned out that the game was played at the grand-master level and that it exhibited the style for which Maroczy was famous. It ended on February 11, 1993, when at move forty-eight Maroczy resigned. Subsequent analysis showed that it was a wise decision: five moves later Korchnoi would have achieved checkmate.

In this case the medium Rollans channeled information he did not possess in his ordinary state of consciousness. And this information was so expert and precise that it is extremely unlikely that any person Rollans could have contacted would have possessed it.

Neurosurgeons and Chess Grandmasters

When it comes to the debate around what is consciousness, there is also firsthand testimonies of human consciousness without a functioning brain. The well-known Harvard neurosurgeon Eben Alexander, who was just as insistently skeptical about consciousness beyond the brain as Lord Russell had been, gave a detailed account of his conscious awareness during the seven days he spent in deep coma. In the condition in which he found himself, conscious experience, he previously said, is completely excluded. Yet his experience—which he described in detail in several articles and three bestselling books—was so clear and convincing that it has changed his mind. Consciousness, he is now claiming, can exist beyond the brain.

The above-cited cases illustrate that there is remarkable, and on occasion remarkably robust, evidence that consciousness is not confined to the living brain. Although this evidence is widespread, it is not widely known. There are still people, including scientists, who refuse to take cognizance of it. This is not surprising, given that the evidence is anomalous for the dominant world concept. Those who strongly disbelieve that such phenomena exist, not only refuse to consider evidence to the contrary, they often fail to perceive evidence to the contrary when asking the question of what is consciousness.

Nonetheless, the view and theory of consciousness as a fundamental element in the world is gaining recognition. The Manifesto of the Summit on Post-Materialist Science, Spirituality and Society (Tucson, Arizona, 2015) declared: “Mind represents an aspect of reality as primordial as the physical world. Mind is fundamental in the universe, i.e., it cannot be derived from matter and reduced to anything more basic.”

An In-Formed World

It appears that consciousness is not limited to the individual body and brain; consciousness is a fundamental element in the universe. The universe, as we now know, is not a domain of matter moving in passive space and indifferently flowing time; it is a sea of coherent vibrations. These vibrations give us the phenomena of physical realities such as quanta, atoms, solar systems, and galaxies, and they also give us the phenomena of nonphysical realities: mind and consciousness.

The affirmation that physical vibrations give rise to nonphysical mind phenomena is not just another version of the “hard question” of consciousness research—the problem of how something as material as the brain can give rise to something as immaterial as consciousness. This however is a pseudo-problem, since clusters of vibration do not produce the phenomana of consciousness; they manifest and display them. The cosmos that gave birth to the universe is fundamentally an intelligence, and that intelligence is manifest in—“in-forms”—all phenomena.

The hard question of the brain and consciousness evaporates if we realize that the physical world is a domain, a segment, and hence a manifestation, of the intelligence of the cosmos. The vibrations that produce the phenomena of physical and nonphysical phenomena, including the mind and human consciousness, are part of the reality of the world, a world that is in-formed by, and manifests, the intelligence that is not only “of” the cosmos, but is the cosmos.

Cosmic Intelligence and the Primacy of Consciousness

The vibrations that manifest the cosmic intelligence are not physical entities in the classical sense of the term. They have a physical as well as a nonphysical aspect. Viewed from the outside, every cluster of vibration is a physical phenomenon, a pattern of vibration in space and time. But viewed from the inside—from the perspective of the given cluster—it is a perception, an awareness, a “feeling” of the world in and by that cluster. This internal, seemingly subjective but objectively real aspect is a fundamental feature of the universe that’s been uncovered by the science of consciousness in response to asking, “What is consciousness?”. It is the consciousness-aspect, one that did not emerge in the course of time but was present when this universe was born in the wider reality of the cosmos.

The bottom line is that the phenomena that appear as conscious awareness were not created or produced by the clusters of vibration in which they appear: they are manifested by them. Consciousness is, and has always been, present in all clusters, from quanta to galaxies. It is not limited to those with a complex brain and nervous system, even though the level of its manifestation corresponds to the level of evolution of the clusters that manifest it—chimpanzees manifest a more advanced brain, mind, and consciousness than mice.

The clusters that manifest consciousness in the universe were not, and cannot have been, the product of chance—chance alone does not explain the presence of any cluster of vibration more complex than a hydrogen atom. It does not explain the presence of the simplest of biological organism. Calculations relevant to the theories science of consciousness show that a random mixing of the proteins that constitute that DNA of the common fruit fly would have taken more time than was available since the Big Bang. There is something in the universe—a mind, a principle, or an intelligence—that orders and “in-forms” the phenomena that structure and hold together the phenomena we observe in the world.

The medium of this “in-formation” is the ensemble of the laws that govern events in the universe. Einstein wrote: “Everyone who is seriously involved in the pursuit of science becomes convinced that a spirit is manifest in the laws of the universe—a spirit vastly superior to that of man, and one in the face of which we with our modern powers must feel humble.” Planck came to the same conclusion. He said that we must assume the presence of an intelligence even behind the vibrations that constitute the nuclei of atoms. This must be a universal intelligence. It is the intelligence that not only holds together the proton and the neutron in the nuclei of atoms but holds together atoms in molecules—and molecules in the multi-molecular structures that are the physical objects of the observed universe.

We have reason to maintain that a cosmic intelligence is manifested in ours as well. Evidently, not everything that appears in our everyday awareness is a mark of a cosmic intelligence; our everyday human consciousness is mainly furnished by sights and sounds, textures, odors, and tastes conveyed by our bodily senses. They result from our brain’s decoding of vibrations in our environment. Our eyes pick up a narrow band of vibrations in the electromagnetic field and transform them into shapes and colors of determinate brightness; our ears pick up a likewise narrow if somewhat wider band of vibrations in the air and transform them into sounds of specific pitch and intensity. But sensory experience, while it produces the principal content of our experience of the world, is not the totality of our conscious awareness. Beyond the data of the senses there are images and intuitions, experiences and feeling tones that are not decoding of ambient vibrations by our eyes and ears: they are trans-sensory, “transcendental” elements of consciousness. They emerge into prominence when the everyday operations of the brain are slowed, or are shut down.

Transcendental Experiences

Transcendental experiences are a standard feature of NDEs, but they surface also in other states of consciousness like sleep, and in the hypnogogic states between sleep and wakefulness. They appear in traumatic, uplifting, or otherwise life-transforming experiences. And, if the reports channeled by psychic mediums are true, they emerge following the physical death of the body. That they do stands to reason within the theory of consciousness presented here. Following the demise of the brain, the sensory elements of consciousness are withdrawn, and the transcendental elements alone dominate.

There are vibrations of an extreme low frequency as well. These low-frequency, long-wavelength vibrations are likely to convey elements of the intelligence that in-forms our body and our brain—and in-forms the universe.

Brain Waves

Indirect support for this hypothesis emerging from the theory and science of consciousness comes from the measurements of the EEG frequencies generated by the brain. In everyday states of awareness, pronounced excitations of the brain trigger EEG waves in the gamma domain, a frequency range of up to 100 hertz. The everyday world appears in the beta range, which is between 12 and 30 hertz. Deeply relaxed or meditative states of human consciousness occur in the low-frequency band known as alpha: 7.5–12 hertz. Transcendental experiences occur mainly in the still lower band of theta, between 4 and 7 hertz.

Below theta, we have the super-low range of delta, between near-zero and 4 hertz. Delta waves are normally produced by the brain and consciousness only in deep sleep. But there are exceptions. The brain of some psychic healers has been known to descend into this region while they are engaged in healing. And spiritual leaders in deep meditation also function in this super-low region, although they are not in the unconscious state of deep sleep.

We need to revise the widespread assumption that non-ordinary “spiritual” experiences occur at a high-frequency domain. They do not occur above the frequency of everyday experiences, but below it. Ordinary, bodily sense-based experience is not the totality of human experience, only a small part of it. We are a cluster of vibration that manifests phenomena of a far wider range than the narrow segment that gives us the sensory data the old theories of the brain and consciousness told us is the totality of our experience of the world.

This article on what is consciousness is excerpted from The Immortal Mind: Science and the Continuity of Consciousness beyond the Brain by Ervin Laszlo. Printed with permission from the publisher Inner Traditions International.

Consciousness, brain, neuroplasticity

Subjectivity, intentionality, self-awareness and will are major components of consciousness in human beings. Changes in consciousness and its content following different brain processes and malfunction have long been studied. Cognitive sciences assume that brain activities have an infrastructure, but there is also evidence that consciousness itself may change this infrastructure. The two-way influence between brain and consciousness has been at the center of philosophy and less so, of science. This so-called bottom-up and top-down interrelationship is controversial and is the subject of our article. We would like to ask: how does it happen that consciousness may provoke structural changes in the brain? The living brain means continuous changes at the synaptic level with every new experience, with every new process of learning, memorizing or mastering new and existing skills. Synapses are generated and dissolved, while others are preserved, in an ever-changing process of so-called neuroplasticity. Ongoing processes of synaptic reinforcements and decay occur during wakefulness when consciousness is present, but also during sleep when it is mostly absent. We suggest that consciousness influences brain neuroplasticity both during wakefulness as well as sleep in a top-down way. This means that consciousness really activates synaptic flow and changes brain structures and functional organization. The dynamic impact of consciousness on brain never stops despite the relative stationary structure of the brain. Such a process can be a target for medical intervention, e.g., by cognitive training.

Introduction

I am the master of my fate:

I am the captain of my soul

On Friday evening, at 6:30 pm, on the 4th of August 2006, at the age of 66, while sitting at his table, holding his head with his right hand, I.K. suddenly fell down on his face. He could not move his right leg and arm, neither could he call for help as his ability to speak has been lost. It was later found that his left common carotid artery was obliterated, and stopped supplying blood and oxygen to the left half of his brain. I.K. experienced a disastrous ischemic stroke: within a few minutes almost a quarter of his brain was destroyed, with the dramatic consequences of a paralysis of the right side of his body (hemiplegia), a loss of speaking and comprehension capabilities (aphasia) and inability to write (agraphia).

In this difficult situation, I.K. could still listen to the doctors around him who discussed his situation. At that time, the neurologists could see that I.K. had suffered severe structural damage and had little hope for his recuperation. But, a year later it became evident that I.K. had experienced an unexpected rehabilitation. Four years after his incident, I.K. could already play the piano with his left hand, write books and poems, paint and exhibit his paintings to the public.

What has happened? One potential explanation had to do with the fact that I.K. had an exceptionally developed right hemisphere (the intact one), which had been enhanced by years of playing piano and painting in his free time. No doubt that these activities have played an important role in his surprising recovery. But there is an additional second explanation. In one of his poems written after his incident, I.K. presented his decision to conduct a new form of life: “I want to talk words of wisdom, but I know that my mouth will betray me when I speak … So what is left for me? I have the will to live, not as I want, but as I can.” This decision was taken despite his dramatic symptoms that included difficulties in writing (dysgraphia), word repetition (perseveration), new words creation (neologisms) and more. It was a conscious decision that represented an act of will and can be considered the source for his astonishing rehabilitation.

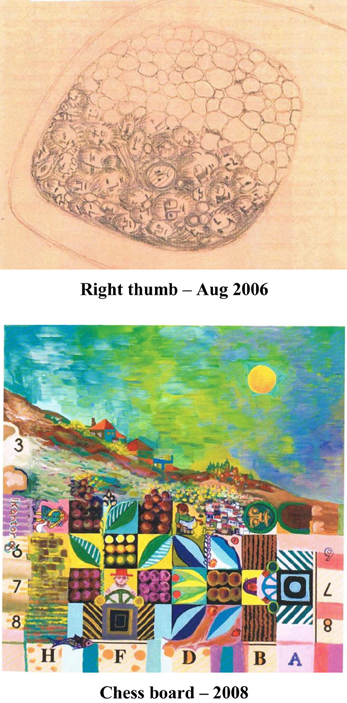

Twenty two days after his stroke he created the following picture which shows the paralyzed thumb of his right arm half covered by heads and half empty. The picture demonstrates his struggle to understand his new state. Two years later he painted a city as a structure of chess maintaining houses, entitled by him “Chess board,” image of his rehabilitation.

It is worthwhile to note that it was I.K.’s linguistic, communication, and expressional capabilities that have recovered but less so his motor skills. The secret of this marvelous transformation might have been rooted in his power of will and firm decision to live in the best possible way he can, even though it is severely limited. An involvement of a top-down effect of consciousness on the neuroplasticity of his brain may explain the rehabilitation of I.K., unlike many others in his state.

Cases of patient recovery after stroke have been reported by Norman Doidge who wrote in his book:

The human brain can change itself, as told through the stories of the scientists, doctors, and patients who have together brought about these astonishing transformations … Some were patients who had what were thought to be incurable brain problems; others were people without specific problems who simply wanted to improve the functioning of their brains or preserve them as they aged. For 400 years this venture would have been inconceivable because mainstream medicine and science believed that brain anatomy was fixed (Doidge, 2007).

These words imply that consciousness and will can have an important role in brain recovery, but might not be always sufficient for certain kinds of brain damages. Brain recovery is more common in brain which preserve consciousness, memory and cognition. It is less common either in long unconscious states, or in brainstem lesions that are less plastic, have less redundancy, and recover very rarely if at all. When I.K. said: “I want to talk words of wisdom, but I know that my mouth will betray me when I speak” he intuitively recognized this distinction. He felt that his thinking and language capacities might recover, but less so his motor skills that are needed for speaking.

The purpose of this article is to discuss the controversial coexistence of a two-way interrelationship between consciousness and brain biochemistry and neural networks. According to serial and modular bottom-up theories, brain perception extracts features from world reality through the senses. Perception is integrated through higher regions and functions of the brain and may finally involve attention and consciousness.

The philosopher Remo Bodei has suggested that in wakefulness the personality is much more unified and under the control of reason, while in dreaming various personalities tend to exist in parallel in a state of delirium. In other words, a state of consciousness is reached in a converged and ordered mode, achieving gestalt, while a state of dreaming is reached in a diverged and confused mode. Converged mode invites a unified mentalization while diverged mode invites differentiation and plurality. Both of these modes are needed for normal life. In order to translate this concept into a horizontal-vertical axis, the upward movement attempts to ascend to rationality and gestalt, while the downward movement to distributed and fragmented functions. An attempt to draw powers from a unified function to affect distributed functions and structures seems possible if the integrative process can overcome local lesions.

At this point we have to make a distinction between the degrees of gestalt reached by different individuals at a time of injury. According to this view, an interference to bottom-up and top-down processes may vary from one individual to another and influence the elaboration of consciousness. Thought and consciousness are activated by sense-data, but on their turn initiate parallel and interactive processes in the brain where both lower levels (e.g., perception) and higher levels of cognition (e.g., memory, conceptual systems, and world knowledge) occur simultaneously and interactively.

The dynamic nature of the brain is maintained by its neuroplasticity which is closely related to consciousness. In his book, Norman Doidge wrote:

The idea that the brain can change its own structure and function through thought and activity is, I believe, the most important alteration in our view of the brain since we first sketched out its basic anatomy and the workings of its basic component, the neuron (Doidge, 2007).

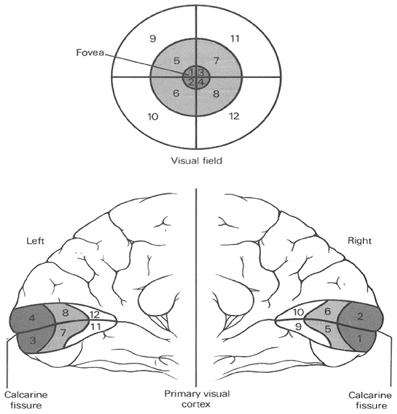

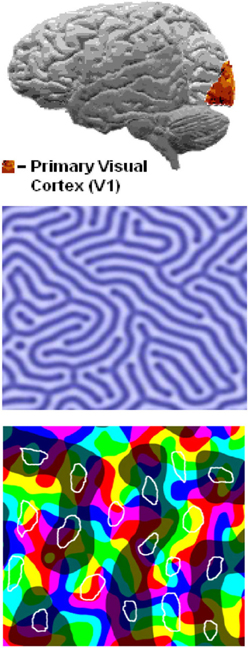

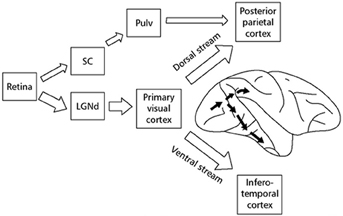

Vision is a sense that has been researched the most of all senses. During the twentieth century there were major steps that have contributed to our understanding of visual complexity. In 1916, Holmes and Lister discovered the retinotopic distorted mapping in the striate cortex (V1 through V5). Holmes and Lister examined and observed 2000 wounded soldiers, who had devastating brain injuries combined with vision impairments. They documented each of the cases within diagrams of the back of the head, where the position of the wound was represented approximately on a diagram of the back of the head. Horizontal lines represented the distance of the plane above the inion, and vertical lines represented the distance from the middle line of the skull. The location of the wounds were then compared with the character of his blindness for each of the soldiers. A reasonable conclusion was reached, which was that visual information is received in the retina and transferred to the primary visual cortex, where it is kept in the form of an image or representation. Holmes and Lister defined the brain area which is the “cerebral localization of vision, and more particularly … the representation of different regions of the retina in the cortex” (Holmes and Lister, 1916).

It is a part of visual perception circuits in the brain and support a bottom-up theory where visual information flows through the brain, first perceived in the retina and then integrated and interpreted in the cortex.

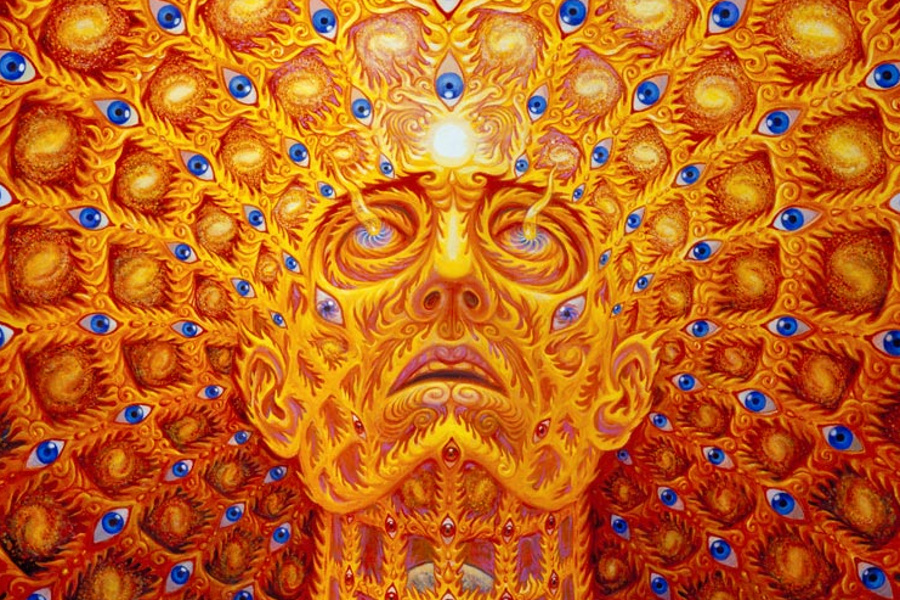

In the early years of the 1960th, (Leary and Alpert, 1962) conducted their controversial research on “The psychedelic hallucinogenic effect of drugs” using psychotropic substances (mostly psilocybin mushrooms and LSD). They demonstrated that biochemistry at the synaptic level forms a basis for changes in vision.

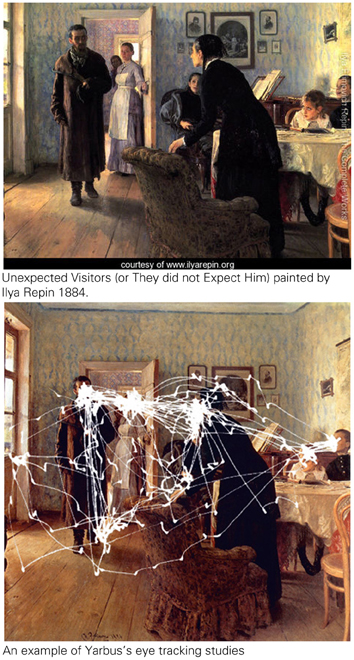

In 1965, (Yarbus, 1967) published his book on eye movements and vision which was based on simple methodology, but had followed an extremely perseverant work. Yarbus discovered “the predominant preferences for faces of the brain perception,” which means that visual perception is not a replica of what comes to vision. He also demonstrated that eye movements are task oriented and are different in cases of free observations than in cases of conscious efforts to record specific information from a scene (Yarbus, 1967).

Since Yarbus, task oriented eye movements are commonly referred to as a top-down process where conscious goals can direct low level functions of perception.

In 1981, Hubel and Wiesel received a Nobel Prize for discovering “The specific orientation of columns and layers perpendicular to the surface of primary visual cortex—V1.”

They could show that the brain of cats can change after they were blinded in one eye. The portion of the cat’s brain associated with the blinded eye has changed to process visual information from the open eye. This research contributed to the understanding of neural plasticity of the visual system in the brain that follows experience.

In 1988, Livingston and Hubel described “The visual pathways of form, color, depth, motion and perception.” Their theory showed a bottom-up flow of visual information from the retina, through the optic nerve to the lateral geniculate nucleus, then the primary visual cortex, and finally the extrastriate cortex. Each of these brain areas performs a specific processing of the visual information and provides its output to the next area:

The primate visual system consists of several separate and independent subdivisions that analyze different aspects of the same retinal image … Moreover, perceptual experiments can be designed to ask which subdivisions of the system are responsible for particular visual abilities (Livingstone and Hubel, 1988).

In 1995, Milner and Goodale described “The Visual Brain in Action” with two separate dorsal and ventral streams of visual pathways that have however “multiple connections between them” and “a successful integration of their complementary contributions.” They suggested an unknown interaction among these streams and other parts of the brain that achieves a purpose directed performance of the visual system.

How the two streams interact both with each other and with other brain regions in the production of purposive behavior (Milner and Goodale, 1998).

This infers that in order to be able to achieve visual perception of the surrounding world, the whole nervous system has to work within a dynamic structure of connectivity and complexity, which can be termed the “gestalt brain.”

Researchers in Indiana University and Lausanne University Hospital have suggested the term connectome, for a brain network of neurons and their interactions (Sporns et al., 2005). Their suggestion was followed in 2009 by the creation of the Human Connectome Project, whose focus is to build an anatomical and functional network map of the human brain. The Human Brain Project of Henry Markram consists of building a computerized human brain able to simulate a bottom up fashion of artificial brain, in which the top-down effects are not expected to be reached.

Tononi, Edelman and Sporns have responded with a concept of “two fundamental aspects of brain organization” that seem to be in conflict: “the functional segregation of local areas that differ in their anatomy and physiology contrasts sharply with their global integration.” They consider complexity as the major element of the brain vision system and have tried to elaborate methods of measuring it (Tononi et al., 1994).

Dynamic neuroplasticity belong also to the high levels of complexity of the brain circuits. In the visual cortex, new connections are developed after birth and attain their specificity by pruning. Circuit selection depends on visual experience, and the selection criterion is the correlation of activity (Lowel and Singer, 1992). At the highest level of complexity the brain gestalt creates consciousness and the first stage of a top-down pathway is realized. A number of computational models were developed mimicking the gestalt phenomena exemplified by the perception of a visual scene and its segmentation into objects (Wang and Terman, 1997).

The realization of vision at its highest level of complexity is coincident with the achievement of the same level of complexity of other senses, and at this point a certain biochemical constellation characterizes the whole brain.

The disastrous ischemic stroke of I.K., blocked within minutes his brain gestalt. The recuperation process, in the following weeks, made possible the restoration of a certain level of gestalt, which made possible the conscious decision “to conduct a new form of life.” The surprising atypical rehabilitation occurred as a result of the influence of the top-down consciousness effect on brain biochemical constellation, neuronal organization and function.

The initiation of brain processes in the higher brain regions results in an activation of lower brain regions, or the influence of the state of consciousness, on structures of the brain, at bio-chemical and neuroplasticity levels. Neuroplasticity occurs through cellular changes due to learning and memorizing, but also within large-scale changes of cortical remapping in response to injury. Neurogenesis of brain cells can take place in certain locations of the brain, such as the hippocampus, the olfactory bulb, and the cerebellum.

We would like to suggest that the content of consciousness can change without sensorial inputs, as is the case in dreaming. Changes in memory involve continuous structural changes in the brain, both during wakefulness and during sleep. This does not entail a dualistic approach to consciousness and brain but rather another aspect of the living brain as also suggested by Tononi, Sporns, and Edelman. We would like to suggest that top-down and bottom-up processes of consciousness and brain are two aspects of the same complex dynamic and plastic nervous system.

Consciousness, Brain, Interaction

But the will is by its nature so free that it can’t ever be constrained. … And the activity of the soul consists entirely in the fact that simply by willing something it brings it about that the little gland to which it is closely joined moves in the manner required to produce the effect corresponding to this volition (Descartes, 1649/1985, Vol. I: 343).

But when the soul uses its will to determine itself to some which is not just intelligible but also imaginable, this thought makes a new impression in the brain, and this thought is not a passion in it, but an action which is properly called imagination (Descartes, 1645/2007: 119).

The famous philosopher is most known for his definition of a human being as an entity composed of a thinking mind and a physical body. Descartes was puzzled by the impact of the will and thought on the brain, which seems to contradict the laws of physics. He was of the opinion that the will can result in thoughts that are based both on sensorial experiences and self creative imagination, and that thoughts can actually move the brain. Since his time, the Cartesian mind have been replaced by a more modern concept of consciousness and the brain has took the place of the body to form the “hard problem of consciousness” as defined by the philosopher David Chalmers (Chalmers, 1995). It has been often said that consciousness is an illusion (e.g., Dennett, 1992) and so is free will (e.g., Wegner, 2002). Every event in the world is caused by other prior events in compliance with the laws of nature. And according to the laws of nature, states of the brain cause human thoughts and feelings. This approach is consistent with the natural sciences such as physics and chemistry and denies that an immaterial substance without a mass can cause a material substance to move directly or indirectly. By the same token, traditional neuroscience has defined that a destruction of a major portion of the left hemisphere of the brain in a right dominant person should result in the elimination of all language capabilities independent of any conscious act of will (Popper and Eccles, 1977).

But, writes philosopher John Searle, to accept a scientific view of consciousness does not entitle that consciousness does not exist. In fact, he thinks that both the brain and consciousness do exist, while consciousness is a higher level view of the brain:

• Conscious states, with their subjective, first-person ontology, are real phenomena in the real world.

• All forms of consciousness are caused by the behavior of neurons and are realized in the brain system, which is itself composed of neurons.

• Conscious states … exist at a level higher than that of neurons and synapses. Individual neurons are not conscious, but portions of the brain system composed of neurons are conscious.

• Because conscious states are real features of the real world, they function causally.

• Consciousness is a system-level, biological feature (Searle, 2004: 112–115).

According to Searle, there is no problem in changing consciousness and by that causing the brain to change. A change can be made in the highest level of the brain system or in its lowest level, and the results will include changes in both neurons and consciousness.

We consider consciousness as the result of the growing complexity of connectome activities. Loss of consciousness due to a damage to the cerebrum is often recoverable, while loss due to damage to the brainstem is not. Major damages to the brain may be recovered and consciousness regained through the brain capacity for physical and functional change. However, when there is a vast damage to the brain and the brainstem (the major pathway from the external world to the internal world), consciousness is completely and permanently lost. Brain death and unrecoverable coma with unconsciousness are among these terminal cases, in which neuroplasticity is mostly absent. We can conclude that consciousness favors brain plasticity.

Block and MacDonald (2008) consider two types of consciousness. A phenomenal consciousness that goes beyond cognitive accessibility and a narrower access consciousness “a subject can have an experience that he does not and cannot think about.” Phenomenal consciousness consists of rich experience and feelings, and only part of it reaches thoughts. “although much of the detail in each picture is phenomenally registered, it is not conceptualized at a level that allows cognitive access.” Access consciousness consists of information held in the cognitive system for the purposes of reasoning. Accordingly, there is a more localized core neurological basis for phenomenological consciousness, and there is a broader total neural basis which initiates a level of access consciousness, e.g., a level that involves abstract concepts and language. The core neurological basis can interact with the total neural basis in both a bottom-up and top-down fashions.

Block and MacDonald think that the brain records experiences within a phenomenal consciousness in core neural bases of consciousness. They provide an example of the fusiform face area, at the bottom of the right temporal lobe in the brain, which is activated with a visual experience of faces, and might be regarded as the core neural basis of face perception. Not like phenomenal consciousness, access consciousness involves the whole brain or the gestalt brain, which Block and MacDonald call the total neural basis of consciousness. Gestalt brain includes working memory, attention, high level information processing and integration, rationality, intentionality and introspection, achieving a high state of consciousness which can in turn influence changes in specific parts of the brain structures and functions, language, thoughts and reports (Block, 2005; Block and MacDonald, 2008).

What can be said of access consciousness as a function of the whole brain? It is essential to the sense of the self. It can include imagined objects and events independent of having experience. It is capable of creative and seemingly uncaused function. That is, it can initiate a chain of events without identifiable causes. We have many evidences that consciousness can cause physical changes. It has features such as intentionality and purpose that are hard to explain by past events. It can change itself and it has a self healing capacity which means that in general it can both improve and cure itself—at least to a certain extent. These capabilities of consciousness have been utilized in rehabilitation plans for patients who suffered brain strokes, or for improvement of attention and memory decline in old adults by cognitive training programs (Smith et al., 2009).

Levine (1983) has introduced the term “the explanatory gap” and later Chalmers (1995) has coined “the hard problem of consciousness,” both expressed the opinion that consciousness has a subjective basis that can not be observed and experienced by a third party neither can it be explained by reductive methods—namely by empirical sciences. According to them, it is possible to describe processes in the brain in a scientific objective way, based on observations, but it is not possible to describe personal experience in such a way.

Even without a scientific explanation, the interrelationship between consciousness and brain activity exists in both senses, the observable and the subjective. The paradox of consciousness arises from the fact that even though we do not have a scientific description and explanation of access consciousness and subjectivity based on brain structures and functions, there are still clear evidences of correlation and even causal relations between them. Using Block and MacDonald’s concepts of consciousness we can conclude that the content of consciousness can be changed by experience, but also outside of experience.

Consciousness, Brain, and Language

At the center of research of both human brain and cognition stays language. Consciousness has an interesting and important relationships with language. Thoughts can be changed by language, sounds, articulation, learning, written text, concepts and associations. Human beings use language all the time for both communication and for thinking. Language provides a frame for beliefs and presumptions and enables deliberation. The interrelationship between thoughts, language and brain structures and functions has been demonstrated by fMRI studies.

fMRI demonstrates that language effects areas in the brain. Different parts of the brain may be activated by different linguistic content. For example, emotional text can cause activity in parts of the brain that have to do with emotions within the limbic system, such as the amygdala, while decision process may activate other areas such as the prefrontal cortex. Language activates Broca’s area for articulation and Wernicke’s area for comprehension, both reside in the left brain hemisphere. Some of the linguistic activities that take place in wakefulness stay with us and become stable in the form of long term memories.

The interrelationship between the content of consciousness and brain activity as demonstrated by language seems to be concomitant. But how are experiences, thoughts and other mental events recorded in the brain? What happens when we study a new language or develop our knowledge and skills of our first language? Such activities start with consciousness and some brain activity (as can be observed by fMRI and other imaging technologies), and with acquisition of new short term explicit memories, that may later become long term and implicit through farther changes in the brain. On their side, practicing syntactic, semantic and pragmatic aspects of language, and knowledge acquisition might be accompanied by the development of automatic unconscious performance of new skills and knowledge. Still later, changes in the brain can also reverse the process, i.e., erase memories and eliminate past knowledge, including linguistic knowledge of words and their meanings. Language, consciousness and the brain change together dynamically and interactively, in ways that can be regarded as both bottom-up and top-down. Within this interaction, language is used as a cognitive tool, but it also forms a constitutive part of cognition itself (Dascal, 2002).

There is an inherent tension between the bottom-up approach which explores the brain in an analytic and modular way and strives to explain the brain, and from it consciousness, by an ensemble of neuron cells and their associated biochemical processes, and a top-down approach that considers the brain as a complex ever changing living system with integrated and interactive parallel functions that appear in the form of consciousness.

Neuroscientist Eric Kandel has made a distinction between implicit memory that is acquired involuntarily “from the bottom up” and assists automatic forms of response to stimulation, and “spatial memory” which serves consciousness and is the result of willful “top-down” registration of new memories in the brain hippocampus, a process triggered by voluntary attention originated in the cerebral cortex.

Language is at the center of both bottom-up and top-down approaches. A bottom-up approach would require a physiological localization of language faculty that would go from sounds and phonemes, and all the way to meanings of words, sentences and understanding of human discourse. Being connected to both the public world and to the private thought, it is a bridge between the physical and the mental. Localization efforts to find the physical parts that establish mental functions in the brain were initiated by neuroanatomist Franz Gall more than 200 years ago. The search for a speech center in the brain made considerable progress in the 19th century, with the findings of Paul Broca who worked with aphasia patients and defined the so-called Broca’s area as responsible for articulated language. A different opinion was presented by his contemporary neurologist John Jackson who thought the Broca’s area could block articulation and be essential for it, but is only a link in a chain that involves the whole brain. More recently philosopher Karl Popper and neurophysiologist John Eccles have jointly expressed their opinion that consciousness and brain interact through a speech center within the left cerebral hemisphere of the brain (Popper, 1994; Popper and Eccles, 1977). But the real existence of such a speech center or even the allocation of speech articulation, hearing, and understanding to specific locations in the brain is still controversial.

Schnelle (2010) suggests a three fold research into language in the brain to try and understand the relations between language and brain. He suggests a combined study of linguistics, psychology (which he says is the phenomenological study of the mind), and neurocognitive science (to which he refers as biology). A new interdisciplinary triangle of interdependent perspectives results from the joint consideration and comparison of formal structures, conscious phenomenological images, and brain architecture, and their functions in language. The idea of Schnelle is to look for basic brain networks and structures that represent pieces of knowledge or memories, and try to relate them to language. Such brain functional neural networks are distributed over relatively large areas within the brain and are termed “cognits” by him. He cites Joaquin Fuster who defined a relation between cognition and brain networks as follows:

Cognitive functions, namely perception, attention, memory, language, and intelligence, consist of neural transactions within and between these networks (Fuster, 2006).

Schnelle adds that pieces of knowledge, i.e., cognits, are embedded in neural networks largely through language hearing and speaking and later also reading and writing which guide imagination and abstract structuring. Fine-tuning of brain networks will influence both the automatic non-conscious language production, and the conscious articulation of ideas, plans and knowledge systems of thoughts. Instead of looking for specific static neuron structures in the brain, we should look for dynamic (plastic) distributed networks, which form pieces of linguistic knowledge (cognits), and for their interaction to form a cognit complex. In a way, dynamic conscious ideas cause changes in the brain.

One important cognitive resource to establish both cognition and cognits is memory. It is possible to examine changes in consciousness and the brain through the prism of dynamic memory, recording and forgetting. Short term memory or working memory is so called because of its vulnerability—it does not hold memories for long and presumably has a minor permanent effect on the brain. Long term memory is more durable and involves permanent changes in the brain through creation of proteins, and formation and dissociation of neural networks (Kandel, 2006). We now turn to examine how long term memory develops and changes during sleep.

Consciousness and Brain During Sleep

So long as the mind is joined to the body, then in order for it to remember thoughts which it had in the past, it is necessary for some traces of them to be imprinted on the brain; it is by turning to these […] that the mind remembers. So is it really surprising if the brain of […] a man in a deep sleep, is unsuited to receive these traces? (Descartes, 1649/1985, Vol. II: 247).

Descartes believed that memories are formed from thoughts during conscious wakefulness only. Memory encoding and retrieval take place most effectively during wakefulness (Diekelmann and Born, 2010), but sleep also promotes the consolidation of newly acquired information in memory and its integration within pre-existing knowledge networks (Karni et al., 1994; Askenasy et al., 1997). Memory consolidation during sleep is often considered as an off-line brain process of stabilization of such newly acquired information, but there is also consolidation of false memories of events that never happened. Acquired information is transformed, restructured, abstracted, integrated with previously acquired memories, prioritized according to its emotional significance, distorted, inferred and combined with false memories within the process of memory consolidation during sleep (Payne et al., 2009).

Memory consolidation involves structural changes in the brain. The creation of proteins, changes in neural pathways and the creation, destruction, enhancement, and regress of neuronal synapses which are parts of the dynamic neuroplasticity of the nervous system. It is an important phase in learning of both procedural (how to do) and declarative (about) knowledge. Long term memories can become implicit, automatic and uncontrolled such as in riding bicycles, and explicit such as records of events and facts. Consciousness is essential for an episodic and explicit memory acquisition. When consciousness is abolished as happens during coma or epileptic seizures memory acquisition and its associated brain processes stop. It can be inferred that neuroplasticity is a physical quality of the nervous system that can be caused by changes in consciousness, which by themselves can be caused either by explicit sensorial inputs or implicit internal states of mind.

Sleep has been considered by Diekelmann and Born as a state where behavioral control and consciousness are both lost. However, dreams can be recalled upon waking-up. World events such as loud noises can be monitored while sleeping, they can participate in dream developments, and can interrupt sleep. Some forms of learning and post-learning as well as problem solving continue during sleep. Post-learning sleep not only strengthens memories but also induces qualitative changes in their representations and so enable the extraction of invariant features from complex stimulus materials, the forming of new associations and, eventually, insights into hidden rules (Diekelmann and Born, 2010). It is evident that some form of consciousness exists in this state.

Dreams are considered as a mixture of false and true events, at least partially caused by consciousness and result in real changes in the brain such as the formation of new neuron networks. Diekelmann and Born (2010) present a view that memory systems compete and reciprocally interfere during wakefulness, but disengage during sleep, allowing for the independent consolidation of memories in different systems. Nir and Tononi consider dreaming to be a state where:

Human brain, disconnected from environment, can generate an entire world of conscious experiences by itself, The dreamer is highly conscious (has vivid experiences), is disconnected from the environment (is asleep), but somehow the brain is creating a story, filling it with actors and scenarios, and generating hallucinatory images (Nir and Tononi, 2010).

The common denominator of many theories trying to explain dreams is their implicit perception. Such theories include the cognitive theory of dreaming of Hall, who stated:

The images of a dream are the concrete embodiments of the dreamer’s thoughts; these images give visual expression to that which is invisible, namely, conceptions (Hall, 1966).

And the activation-synthesis hypothesis of Hobson and McCarley which suggested an automatic and periodic brain stem neuronal mechanism, which generates and determine the spatiotemporal aspects of dream imagery, which are then compared and synthesized with stored memories (Hobson and McCarley, 1977).

In order to analyze the brain mechanism of dreams and hallucinations, we have to switch from sensorial perception to extrasensory perception or from explicit perception to implicit perception. The field where sensorial perception interfere with extrasensory perception is the field of dreams and is different from hallucinations.

The major difference between the two states of sleep and wakefulness is the switch of perception from implicit to explicit. The blocking of implicit perception is reached by the Gestalt brain during wakefulness. During sleep, many parts of the brain show much reduced activity while others continue to be active. Certain sensorial inputs to the brain are disconnected, as well as certain outputs, as muscles and movement control. Consciousness changes and decreases in functions including voluntary control, self awareness and reflective thought. But consciousness also increases in its emotional involvement and impaired memory (dream amnesia) (Nir and Tononi, 2010). Nir and Tononi conclude that “dream consciousness can not be reduced to brain activity in REM sleep,” and that dream is a powerful form of imagination where presumably brain activity flows in a “top down” manner.

In a state of dreaming the external world is almost absent and an internal world exists in the brain and takes over consciousness. The content of dreams is the segregated and integrated external reality deposited in the hippocampus, posterior temporal fusiform gyrus, orbito-frontal area, limbic area, and all over the brain which takes the place of reality. The moment we switch to the wake state the implicit perception is differentiated from the explicit perception and is recognized within consciousness to be a false perception.

The unreal aspect of dreaming is later recognized by the dreamer, and dreams are mostly separated from real experiences. Dreamers are conscious when awakened that the visual imagery that they have experienced was false due to the instant instauration of the Gestalt brain. In the wakefulness state there are normally no self-generated implicit perceptions that are not caused by real experiences. Upon arousal from a dream, consciousness allows the interpretation of the imagery as false. It is a chaotic combination of recollected experiences presented in the mind as occurring now. The ability to experience past implicit visual perceptions characterizes dreams, as the ability to experience explicit perception characterizes visual consciousness during wakefulness.

What differentiate phenomenological explicit from implicit perception are (a) the bizzarness, (b) threatening, (c) vivid colored faces, (d) absence of bodies and limbs, (e) lack of identification and recognition. The switch to wakefulness may be not concomitant with conscious recognition of false imagery, sometimes a longer duration of wakefulness is requiered. Interpretation in wakeness state of the visual imagery as being real means pathology.

Hallucinations are implicit perception, internally generated by the brain, which instead of appearing in the dream state appear in wakefulness, e.g., due to structural lesions of the brain.

During the sleep state a concomitant implicit and explicit perception may occur in lucid dreaming. In the wake state a concomitent implicit and explicit perception may occur in a hallucinatoric brain. In a normal physiologic brain the implicit perception appears as a past experience and is called reminding or remebering. The consciousness of distinguishing the present from the past allows the implicit perception to appear as memory. The fourth element of existence “the time” differentiates memory from implicit perception.

The gestalt waking brain is obliged to separate the implicit from the explicit perception, in order to allow consciousness. If not, the implicit is integrated in the explicit and the extrasensory perception becomes hallucinatory mixture of real and unreal.

The activity of the brainstem and cortical areas during sleep allow an implicit perception to become explicit. The switch to wakefulness may not be concomitant with consciousness of false experiences.

Domhoff has developed a “cognitive theory of dream” that suggests a conceptual system which forms the basis for knowledge and beliefs. During wakefulness it serves for thought and imagination. In sleep it is active within the cortical mature neural network, when external stimuli are blocked and conscious self-control is lost:

A “dream” is a form of thinking during sleep that, as already briefly stated, occurs when there is (1) an intact and fully mature neural network for dreaming; (2) an adequate level of cortical activation; (3) an occlusion of external stimuli by the sensory gates located in the thalamus; and (4) the loss of conscious self-control, i.e., a shutting down to the cognitive system of “self.” … a “dream” is also what people remember in the morning, so it is in this sense a “memory” of the dreaming experience (Domhoff, 2010).

Creativity can be based on autonomic brain events that are initiated in higher brain parts which do not result directly from experience and information that might otherwise be received from lower brain parts. A discontinuity of brain structures which can be accompanied by separate processes and on-going brain changes, together with the capacity of imagination and dream recollection as initiated within the brain during different states of consciousness, may be the basis for an “explanatory gap” and a “hard problem of consciousness.” Top-down and bottom-up processes may be occasionally disconnected leading to a possibility of independent psychological reality, that is not directly caused by sensorial inputs, or otherwise emerge from such inputs in a complex delayed and dynamic ways that can not be inferred from direct observations of lower brain processes.

John Searle makes the same point. He writes that a dream of something red may involve a change in the content of consciousness that is not based on experience but is created in the brain:

Like many people, I dream in color. When I see the color red in a dream, I do not have a perceptual input that creates a building block of red. Rather the mechanisms in the brain that create the whole unified field of dream consciousness create my experience of red as part of the field (Searle, 2004: 155).

Summary and Conclusions

A high-level phenomenon is weakly emergent with respect to a low-level domain when the high-level phenomenon arises from the low-level domain, but truths concerning that phenomenon are unexpected given the principles governing the low-level domain. Weak emergence is the notion of emergence that is most common in recent scientific discussions. A high-level phenomenon is strongly emergent with respect to a low-level domain when the high-level phenomenon arises from the low-level domain, but truths concerning that phenomenon are not deducible even in principle from truths in the low-level domain … I think there is exactly one clear case of a strongly emergent phenomenon, and that is the phenomenon of consciousness (Chalmers, 2006).

Chalmers defines a system property of weak emergence which corresponds to an analytic, bottom-up construction of knowledge. A bottom-up process may start with some sensory inputs which affect some neurons, that change and form new networks with different strengths of connections. According to such a scientific view, consciousness, memories and thoughts are the result of a neuronal integrated activity. Cases that might be described with the concept of weak emergence of system properties and simple learning have been studied in simple organisms such as the Aplysia californica (Kandel, 2006). One day, it is said, it will be possible to form a dynamic model of neurons, their interconnections and their relative strengths. If achieved, this might result in a conscious behavior or at least as a tool to change and enhance cognition.

Chalmers defines a second concept of strong emergence which requires a high level of system knowledge through a top-down approach to exploration. Chalmers claims that knowledge about consciousness is a case in point, where a bottom-up methods will not do for a complete and detailed explanation. His suggestion follows the ideas of the 17th century philosopher Gottfried Leibniz and those of the 20th century founder of general system theory, the biologist von Bertalanffy (1968). Both promoted the application of a whole system top-down approach to living systems (i.e., animals).

We have suggested in this article that dreams include self generated brain images and are results of implicit perception. They are formed by brain networks in the gestalt brain through the activity of neurons and synapses already consolidated and generating false memories integrated with true memories. In this way dream can change the brain by the activation of relatively large neuron ensembles, eliberated from the consciousness control. We can farther speculate that thinking, moral judgments, complex learning (i.e., language acquisition), and many other mental activities, require a concept of strong emergence of consciousness and top-down brain processes. There are other similar states of affairs that are quite common in biology, e.g., swarm behavior.

The neurophysiologist Sir John Eccles and the philosopher Sir Karl Popper had cooperated to find explanations for consciousness, brain and the self. Popper identified the self with full consciousness which, according to him, controls human action.

Full consciousness … consists mainly of thought processes … The self, or full consciousness is exercising a plastic control over some of our movements which, if so controlled, are human action … The novel structures that emerge always interact with the basic structure of physical states from which they emerged … Mental states interact with physiological states (Popper, 1994: 115, 132).

Eccles introduced his hypothesis of interaction between self-conscious mind and the brain. He presented a hypothesis that the unity of consciousness is provided by itself rather than by neural cells in the brain. He went as far as making the following statements:

The self-conscious mind exercises a superior interpretative and controlling role upon the neural events. The unity of conscious experience is provided by the self-conscious mind and not by the neural machinery (Popper and Eccles, 1977: 355).

The traditional scientific bottom-up methodology concentrates on the analysis of modular substructures and biochemical processes within the brain. A top-down concept elaborates a diverged activity from consciousness and cognition to various structures and functions of the brain. Top-down research has concentrated more on high level study of consciousness and cognition, and has gained its own place by taking a system approach to questions on brain and consciousness. John Searle has a similar observation:

Most researchers adopt the building block approach … It seems very difficult to try to study massive amounts of synchronized neuron firings that might produce consciousness in large portions of the brain such as the thalamocortical system … I am betting on the unified-field approach (Searle, 2004: 155–156).

We have followed the above thinkers by highlighting some facts and evidences that can shed light on these two antithetic approaches. We have tried to view consciousness and brain interaction through an instance of exceptional recovery from a broad and dramatic damage to the brain, and by a demonstration of acquired evidences of neuroplasticity in the nervous system through life cycles of wakefulness and sleep. It is evident that consciousness changes the brain while it is also being changed by the brain. Procedural and declarative memory, their acquisition and consolidation are all changes in the nervous system that involve both consciousness and the brain bi-directionally and interactively.

Richard Davidson has been using concepts and phrases such as contemplative neuroscience, neural-inspired behavioral or mental interventions, putting the mind back in medicine, and mental exercise. He and his team have conducted experiments where meditation was used as a conscious mental practice, while consequential changes in the brain were tested with fMRI. Based on his experiments Davidson has suggested that mental training changes the structure and function of the brain:

Mental training of meditation is fundamentally no different than other forms of skill acquisition that can induce plastic changes in the brain (Davidson and Lutz, 2008).

In a later paper he wrote that

Moderate to severe stress appears to increase the growth of several sectors of the amygdala, whereas the effects in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex tend to be opposite. Structural and functional changes in the brain have been observed with cognitive therapy and certain forms of meditation, we can also take more responsibility for our minds and brains by engaging in certain mental exercises that can induce plastic changes in the brain, it is apparent that both structural and functional connectivity between prefrontal regions and sub cortical structures is extremely important for emotion regulation and that these connections represent important targets for plasticity-induced changes (Davidson and McEwen, 2012).

It is a common experience and has been observed scientifically that the nervous system changes continuously following internal and external events as well as thoughts, imaginations and dreams. Such changes are followed by changes in memory and content of consciousness. It is clear that the damage caused to the brain of I.K. by his stroke changed his consciousness rather dramatically. There is no doubt in our minds that his outstanding brain functions recovery was also the result of his strong will and determination. It was a whole system top-down effect, rather than a property of separate groups of neurons in his brain. This case and other similar cases could lead to a conclusion that medical treatment should target the bidirectional activity of the nervous system, and could better perform if both bottom-up and top-down considerations would be applied in medical interventions, i.e., to add methods that are intended to activate changes in the content of consciousness to more traditional treatments of structural lesions. A combined approach could promote physical and mental health.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Askenasy, J. J. M., Karni, A., and Sagi, D. (1997). “Visual skill consolidation in the dreaming brain,” in Sleep and Sleep Disorders: from Molecule to Behavior, eds O. Hayaishi and S. Inoué (Tokyo: Academic Press Harcourt Race), 361–376

Block, N. (2005). Two neural correlates of consciousness. Trends Cogn. Sci. 9, 46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2004.12.006

Block, N., and MacDonald, C. (2008). Phenomenal and access consciousness. Proc. Aristotelian Soc. CVIII, 289–317. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9264.2008.00247.x

Chalmers, D. J. (1995). Facing up to the problem of consciousness. J. Conscious. Stud. 2, 200–219.

Chalmers, D. J. (2006). “Strong and weak emergence,” in The Re-emergence of Emergence, ed P. Clayton and P. Davies (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press), 244–255.

Dascal, M. (2002). Language as a cognitive technology. Int. J. Cogn. Technol. 1, 35–61. doi: 10.1075/ijct.1.1.04das

Davidson, R. J., and Lutz, A. (2008). Buddha’s brain: neuroplasticity and meditation. IEEE Signal Process. 25, 171–174. doi: 10.1109/MSP.2008.4431873

Davidson, R. J., and McEwen, B. S. (2012). Social influences on neuroplasticity: stress and interventions to promote well-being. Nat. Neurosci. 15, 689–695. doi: 10.1038/nn.3093

Dennett, D. C. (1992). Consciousness Explained. Boston, MA: Back Bay Books.

Descartes, R. (1649/1985). “The passions of the soul,” in The Philosophical Writings of Descartes. Vol. I, II trans J. Cottingham, R. Stoothoff, and D. Murdoch (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Descartes, R. (1645/2007). The Correspondence between Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia and Rene Descartes. Chicago, USA: University of Chicago Press.

Diekelmann, S., and Born, J. (2010). The memory function of sleep. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 11, 114–126. doi: 10.1038/nrn2762

Doidge, N. (2007). The Brain that Changes Itself. New York, NY: Viking Penguin.

Domhoff, G. W. (2010). The Case for a Cognitive Theory of Dreams. Retrieved December 13, 2012 from http://www2.ucsc.edu/dreams/Library/domhoff_2010a.html

Fuster, J. M. (2006). The cognit: a network model of cortical representation. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 125–132. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2005.12.015

Hall, C. S. (1966). The Meaning of Dreams. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Henley, W. E. (1904/1875). “Invictus,” in The Oxford Book of English Verse 1250–1900, ed A. T. Quiller-Couch (Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press), 1019.

Hobson, J. A., and McCarley, R. (1977). The brain as a dream state generator: an activation-synthesis hypothesis of the dream process. Am. J. Psychiatry. 134, 1335–1348.

Holmes, G., and Lister, W. T. (1916). Disturbances of vision from cerebral lesions with special reference to the cortical representation of the macula. Brain 39, 34–37. doi: 10.1093/brain/39.1-2.34

Kandel, E. R. (2006). In Search of Memory: The Emergence of a New Science of Mind (New York, NY: W. W. Norton and Company).

Karni, A., Tanne, D., Rubenstein, B. S., Askenasy, J. J. M., and Sagi, D. (1994). Dependence on REM sleep of overnight improvement of a perceptual skill. Science 265, 679–682. doi: 10.1126/science.8036518

Leary, T. F., and Alpert, R. (1962). Letter to the Editor. The Harvard Crimson.

Levine, J. (1983). Materialism and qualia: the explanatory gap. Pac. Philos. Q. 64, 354–361.

Livingstone, M., and Hubel, D. (1988). Segregation of form, color, movement, and depth: anatomy, physiology, and perception. Science 240, 740–749.

Lowel, S., and Singer, W. (1992). Selection of intrinsic horizontal connections in the visual cortex by correlated neuronal activity. Science 255, 209–212. doi: 10.1126/science.1372754

Milner, D., and Goodale, M. (1995). The Visual Brain in Action. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Milner, D., and Goodale, M. (1998). The Visual Brain in Action. Psyche.

Nir, Y., and Tononi, G. (2010). Dreaming and the brain: from phenomenology to neurophysiology. Trends Cogn. Sci. 14, 88. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2009.12.001

Payne, J. D., Schacter, D. L., Propper, R. E., Huang, L., Wamsley, E. J., Tucker, M. A., et al. (2009). The role of sleep in false memory formation. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 92, 327–333. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2009.03.007

Popper, K. R. (1994). Knowledge and the Body-mind Problem. Oxford: Routledge.

Popper, K. R., and Eccles, J. C. (1977). The Self and Its Brain. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

Schnelle, H. (2010). Language in the Brain. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Searle, J. R. (2004). Mind: A Brief Introduction. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Smith, G. E., Housen, P., Yaffe, K., Ruff, R., Kennison, R. F., Machncke, H. W., et al. (2009). A cognitive training program based on principles of brain plasticity: results from the improvement in memory with plasticity-based adaptive cognitive training (IMPACT) study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 57, 594–603. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02167.x

Sporns, O., Tononi, G., and Kötter, R. (2005). The human connectome: a structural description of the human brain. PLoS Comput. Biol. 1:e42. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0010042

Tononi, G., Sporns, O., and Edelman, G. M. (1994). A measure for brain complexity: relating functional segregation and integration in the nervous system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91, 5033–5037.

von Bertalanffy, L. (1968). General System Theory: Foundations, Development, Applications. New York, NY: G. Braziller.

Wang, D., and Terman, D. (1997). Image segmentation based on oscillatory correlation. Neural Comput. 9, 805–836. doi: 10.1162/neco.1997.9.4.805

Wegner, D. M. (2002). The Illusion of Conscious Will. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Yarbus, A. L. (1967). Eye Movements and Vision. New York, NY: Plenum Press.

Keywords: consciousness, neuroplasticity, memory

Citation: Askenasy J and Lehmann J (2013) Consciousness, brain, neuroplasticity. Front. Psychol. 4:412. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00412

Received: 06 February 2013; Accepted: 18 June 2013;

Published online: 10 July 2013.

Ursula Voss, Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms University Bonn, Germany

Elaine K. Perry, Newcastle University, UK

Ursula Voss, Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms University Bonn, Germany

Copyright © 2013 Askenasy and Lehmann. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in other forums, provided the original authors and source are credited and subject to any copyright notices concerning any third-party graphics etc.

*Correspondence: Jean Askenasy, Sackler Faculty of Medicine, School of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, 69978 Tel-Aviv, Israel e-mail: ajean@post.tau.ac.il;

Joseph Lehmann, Faculty of Humanities, School of Philosophy, Tel Aviv University, 69978 Tel-Aviv, Israel e-mail: josephle@post.tau.ac.il

This article is part of the Research Topic

What Is Consciousness?

What The Brain Does and How it Does It