What president made slaves free

What president made slaves free

Log In

Who Freed the Slaves?

For some time now, the answer has not been the abolitionists.

By Stephanie McCurry

September 13, 2016

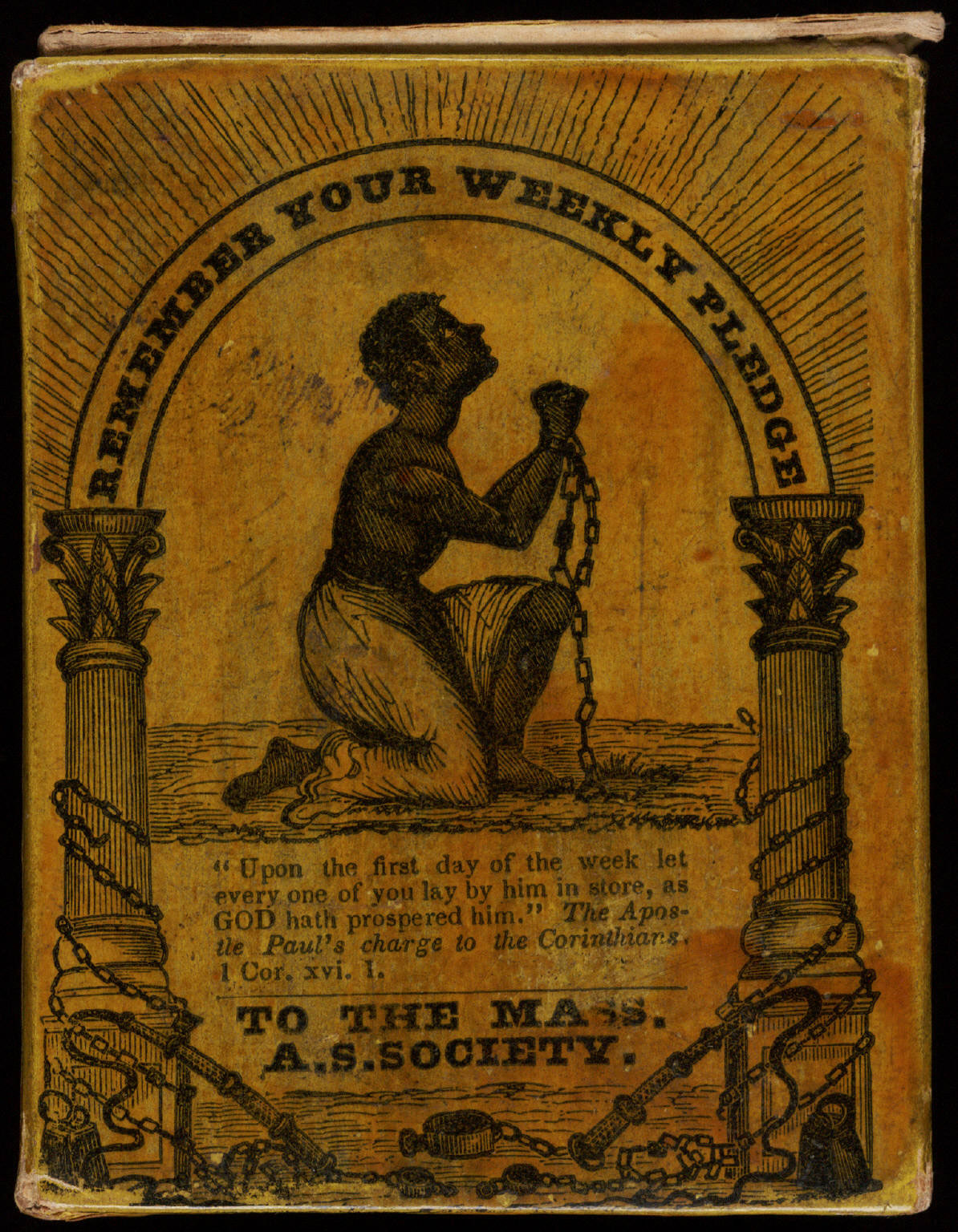

A collection box of the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society, circa 1850. (Wikimedia)

Subscribe to The Nation

Get The Nation’s Weekly Newsletter

By signing up, you confirm that you are over the age of 16 and agree to receive occasional promotional offers for programs that support The Nation’s journalism. You can read our Privacy Policy here.

Repro Nation

By signing up, you confirm that you are over the age of 16 and agree to receive occasional promotional offers for programs that support The Nation’s journalism. You can read our Privacy Policy here.

Subscribe to The Nation

Support Progressive Journalism

Sign up for our Wine Club today.

In the epic battle between the forces of slavery and emancipation in the United States, power was on the side of the slaveholders. This much has always been clear, and never more so than now. To the history of the slave states’ near-monopoly of the federal government and foreign policy in the first republic, scholars and public intellectuals have recently added an accounting of how the money generated by slavery and cotton sluiced through the entire national economy. Profits extracted violently from the labor of the enslaved—4 million people of African descent in the United States in 1860—were the basis of a burgeoning American capitalism and, in that sense, of the new nation itself. It was the original pillaging of black lives and wealth, and it took a civil war and an existential threat to the United States to change that. Emancipation came by the sword. Any attempt to confront our current crisis as a nation takes us back to these foundational facts and brutal racial history.

BOOKS IN REVIEW

The Slave’s Cause: A History of Abolition

By Manisha Sinha

What, then, of the abolitionists? Did they not weigh decisively in the national contest on the side of the slave? Manisha Sinha argues on their behalf in The Slave’s Cause. She is up against a lot. To make the case for the centrality of abolitionists to the emancipation of the slaves, she has to redeem the movement itself from insignificance and its participants from charges of racist paternalism and bourgeois self-interest. Fights about John Brown notwithstanding (was he a terrorist or merely insane?), little scholarship in the recent past has placed much emphasis on the abolitionists as a historical force. Indeed, Sinha calls them “the forgotten emancipationists.” But by far the most daunting challenge she faces is the fact that emancipation came only during the Civil War and the view, now widely held, that it wasn’t primarily the accomplishment of Abraham Lincoln or the Republican Party, but of the slaves themselves, precipitated by the actions they took inside the Confederacy and in their flight to Union lines. “Who freed the slaves?” the question goes. For some time, the answer has not been the abolitionists.

Sinha begs to differ. In The Slave’s Cause, she offers nearly 750 impassioned pages for considering abolitionism as a longstanding progressive force in American life. At stake, she insists, is nothing less than the “potential of democratic radicalism” itself. Hers is a “movement history,” an ambitiously comprehensive account of the abolition movement that reaches back to the American Revolution, “rejects conventional divisions between slave resistance and anti-slavery activism,” and focuses on black abolitionists as the key actors. It was a movement made up of “passionate outsiders,” a radical, interracial movement that addressed “the entrenched problems of exploitation and disenfranchisement in a liberal democracy and anticipated debates over race, labor and empire.” Sinha categorically rejects any criticism of the movement, including the Trinidadian historian Eric Williams’s influential argument that abolitionism arose with the political interests of new industrial capitalists, who sought to exploit free rather than slave labor. “If slavery is capitalism, as the currently fashionable historical interpretation has it,” Sinha writes, “the movement to abolish it is, at the very least, its obverse.” Abolitionists were antislavery but also anticapitalist, anti-imperialist, pro-feminist, and pro-labor. Their criticism of slavery and capitalism was so broad that it makes them the precursor to every progressive and radical movement of the 20th and 21st centuries: Black Lives Matter, Occupy Wall Street, civil rights, international human rights, Black Power, black nationalism, the NAACP, Pan-Africanism, the Wobblies, the Populists, the Popular Front, and the Knights of Labor. Her faith in the abolition movement is boundless and unreserved.

Sinha sees the history of abolition as the “ideal test case of how radical social movements generate engines of political change.” No doubt we could use some inspiration on that front. For the better part of a century, black and white abolitionists together took up the “slave’s cause.” In all of that time, Sinha tells us, the connection between “slave resistance and abolition in the United States proximate and continuous.” Moreover, she insists, “To reduce emancipation to an event precipitated by military crisis is to miss that long and rich history.” But however valuable the recovery of the movement’s history may be—including as a template for 21st-century progressives—the troubling question of causation persists: How far could a Northern movement backing the slave’s cause go toward the emancipation of the slaves themselves—not just the estimated 150,000 fugitives who made it to the North, but the 4 million men, women, and children still in the Southern states in 1860 and held fast in the slaveholders’ grip? How much could Northern radicals acting for the slave actually do to counter slaveholder power—until, that is, the Civil War, when the slaves could finally take their long war to destroy slavery directly to their masters? This is a pressing moral and historical dilemma not easily resolved, even by a true believer.

Sinha’s history of the abolition movement is rich and comprehensive, even to a fault. The movement unfolded over the course of a century in the cities, small towns, and countryside of the Northern states, and she aspires to cover it all. It certainly was an extended “drama in law, politics, literature and on-the-ground activism,” as she says; but for the most part, the drama of human struggle in the movement gets buried beneath the book’s encyclopedic level of detail. Sinha’s default narrative device is the summary list; her book thrums with ideas and arguments, but only the committed reader will stick it out.

Abolitionism came in two waves. It had its early origins in the religious conscience of a few Quakers—men like the French-born Philadelphian Anthony Benezet—but it really came to life in the era of the American and Haitian revolutions. This “first wave” of the movement would last until 1830; although it was interracial and transatlantic from the start, its driving force was the claim to personal freedom advanced by slaves themselves. It included many people, among them an estimated 20,000 runaway slaves from the Southern colonies, who tried to make it to British lines, to Spanish Florida, or to the Patriot armies in the Northern colonies. Those who made it and were not dispersed to the edges of the British Empire after the Revolutionary War became part of another antislavery force: the burgeoning population of free blacks, fugitives, and slaves in the North. Those still enslaved in places like Boston, New York, and Philadelphia also pursued every possible means to achieve freedom, including self-purchase, which involved spending the savings painfully accumulated from paltry earnings to buy themselves and their relatives out of slavery. They also took legal and political action, leaving a clear record of their own revolutionary ambitions. Deploying their one unassailable right, the right of petition, African-American men and women steadily inundated courts and legislatures with petitions for personal freedom throughout the 1770s and ’80s. “We expect great things from men who have made such a noble stand against the designs of their fellow-men to enslave them,” one freedom petitioner put it, sharply skewering the republican pretensions of men still insisting on the legitimacy of African slavery. This is the single greatest strength of The Slave’s Cause: the way it moves the black abolitionist tradition to its rightful place at the center of abolitionist history.

By the mid-1780s, these revolutionary efforts had paid off and all of the New England states and Pennsylvania had formally abolished slavery. A network of abolitionist societies was beginning to emerge, made up mostly of Quakers—but as in the case of the Pennsylvania Society for the Abolition of Slavery and the New York Manumission Society, it also included prominent antislavery patriots like Benjamin Rush and Alexander Hamilton. Nonetheless, the protracted plans for abolition passed by the Northern states—which freed only those born after passage of the acts, and only after long terms of service to compensate their masters—meant that there were still significant numbers of people held as slaves (and plenty of slaveholders as well) in the North well into the 1820s, and in New Jersey, where the process was slowest, until the 1840s. Throughout that long Northern emancipation, the burden of advancing the slave’s cause was borne in no small measure by fragile Northern communities of free blacks and fugitives, people who had once been—or still were—slaves themselves, all menaced by a Fugitive Slave Act imposed as part of the constitutional bargain with slaveholders. None of the abolitionist societies had black members, though Sinha is at pains to show that despite this “de facto exclusion,” they formed strong connections with free black communities and institutions and helped educate the next generation of black leaders. At the very least, her generalizations about the interracial character of the movement would seem to require some temporal restraint.

As the South’s commitment to slavery and cotton deepened in the early Republic and the slaves’ resistance was forced underground, it was black abolitionists in the Northern states who kept the movement alive. As Sinha demonstrates, black abolition was a social movement with deep community roots. It was sustained by a rich web of institutions—churches, mutual-aid and burial societies, schools, and eventually a convention movement and independent newspapers—that simultaneously sought to protect and extend the rights of free blacks while agitating for the abolition of slavery. Among its leaders was James Forten, a founding member of the Philadelphia Free African Society, who petitioned Congress to rescind the Fugitive Slave Act and, in the early 1830s, bankrolled William Lloyd Garrison’s newspaper The Liberator. These were “the first generation of ‘race men,’” as Sinha puts it. By the time of the crisis in 1820 over Missouri’s admission to the Union as a slave state, abolitionists were an organized force, influential enough to shape the restrictionist position in Congress. The movement was growing beyond its base in the black community—but in the first wave, notwithstanding some powerful white allies, black abolitionist men and women were its heart and soul.

That would never change. When William Lloyd Garrison set type on the first issue of The Liberator in 1831, inaugurating the second wave of the abolition movement, 450 of his 500 initial subscribers were African American. Garrison’s commitment to immediate, uncompensated emancipation and his rejection of colonization as any part of an antislavery strategy owed directly to the tradition of black abolition. Garrison’s organization, the American Anti-Slavery Society (AASS), unlike earlier groups, was always deeply—and controversially—committed to interracial organizing, and it drew a contingent of highly principled white members, male and female, despite the social ostracism and personal danger involved in public advocacy of the slave’s cause.

Garrisonians pioneered new organizing tactics, including many that remained the go-to strategies of progressive movements until the age of social media: lecture tours, petition campaigns, lawsuits, movement publications, consumer boycotts, and civil disobedience. They built a network of local organizations that eventually reached every community in the Northeast and Midwest. African Americans joined the AASS, but they kept their own separate organizations and institutions as well, maintaining an unstinting commitment to abolition, black rights, and aid to fugitives over the long haul. They remained the sharpest point of abolitionist defense. Maria Chapman, editor of the antislavery journal Non-Resistant, said that a black abolitionist could convey in a few words an argument that would take a white man all day. She might have been thinking of Charles Lenox Remond, who once said that “complexion can in no sense be construed into crime, much less be rightfully made the criterion of rights.” These are words that outran their time and, sadly, ours as well.

By the 1840s, the movement had experienced a series of bitter schisms. Not all abolitionists could embrace a broad radical agenda, especially women’s rights, and many did not approve of Garrison’s turn toward nonresistance, with its renunciation of partisan politics. One wing of the movement split off and turned to third-party politics, attempting to build a force that could counter the power of slaveholders in the national Democratic Party. Throughout the entire antebellum period, the issue of fugitive slaves—runaways like Frederick Douglass and shipboard rebels like those on The Amistad—inflamed controversy north and south and roiled the political waters. “Slave rebels and runaways put slavery on trial,” Sinha rightly insists.

The passage of a new Fugitive Slave Act as part of the congressional compromise of 1850 pushed the movement into a more militant phase. The law was a devastating development for ostensibly free blacks in the North, who met it with a strategy of armed resistance. The terms of the law made Northern officials and civilians responsible for its enforcement, thereby implicating them in the capture and return of fugitive slaves. Efforts to enforce the law were met with massive resistance, ranging from civil disobedience to violence. Thomas Wentworth Higginson, the abolitionist and friend of Emily Dickinson, observed that the act turned “honest American men into conscientious law-breakers.” The burden of protecting fugitives from recapture and free blacks from kidnapping fell on local vigilance committees, which played a heroic role in the 1850s. Vigilance committees had been a feature of black abolitionism since the Revolutionary era. In the 1850s, they became the front lines of the struggle, working in conjunction with an established network of safe houses—which together constituted the Underground Railroad—strung out across the North and into Canada. Members of vigilance committees alerted fugitives to slave catchers and moved them out before they could be apprehended; they broke into jails and retrieved people already captured; and they engaged in armed confrontations with slave catchers attempting to enforce federal law. Harriet Tubman successfully liberated one man from officers attempting to take him to the docks and back to slavery by fighting them hand-to-hand in the streets of Troy, New York. In Christiana, Pennsylvania, a free black man named Parker who was protecting runaway slaves on his farm sounded the alarm when their Maryland owner and a posse of slave catchers arrived to reclaim them. Twenty armed black men responded, and there was a gun battle in which the slaveholder was killed; the survivors were hustled off to Canada.

White abolitionists played a crucial role in this militant new phase of the movement, not least as legal counsel to fugitive slaves and vigilance-committee members in high-profile trials of the Northern “freedom” principle. The abolition movement had its white heroes and martyrs, men like the sea captain Jonathan Walker and the minister Calvin Fairbank, who both served long terms in Southern prisons for helping slaves escape. And, of course, there was John Brown: Sinha argues that “fugitive slave rebellions” and “revolutionary abolitionism,” as she calls the 1850s phase, constitute the proper historical context for the controversial Brown, who was “not sui generis or an aberrant lone wolf” but rather “personified the abolition war against slavery.” Thus, the analysis of “John Brown’s War” in The Slave’s Cause is coupled with another section on “Lincoln’s War,” under the rubric of “Abolition War.”

But however convenient the argument may be in closing the gap between Northern abolitionists and the events of the Civil War, Brown’s example doesn’t really cinch it. Most fugitive-slave abolitionism, even of the militant sort, was the work of runaway slaves or Northern free blacks, and virtually all of it played out in the Northern states in fugitive resistance to re-enslavement. At Pottawatomie, Kansas, in 1856, John Brown planned murder as a political strategy; at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, in 1859, he attempted and failed to incite a slave rebellion within a slave state. Whatever one ultimately makes of his actions in a moral or ethical sense, Brown’s murky case should have prompted Sinha to a more thoughtful assessment of the radical-democratic potential of the abolitionist movement; this is, after all, one of her main themes. For not only did Brown embrace violence as the only possible winning strategy, but Harpers Ferry illustrated the limits of his politics. Even in its militant form in 1859, the abolition movement essentially had no greater ability to penetrate the South than it had in 1830, no greater ability to hit slaveholders where they lived or take direct action to liberate the growing numbers of men, women, and children enslaved in the South. In that sense, I would argue, John Brown was pretty sui generis, certainly in his actions at Harpers Ferry, and his failure might fruitfully focus our attention on the massive edifice of police power that slaveholders had erected to suppress rebellions and limit the reach of Northern abolitionists. The white-savior model, therefore, was flawed in every respect. As the African-American abolitionist and preacher Henry Highland Garnet put it once, speaking of white abolitionists: “THEY are our allies—OURS is the battle.” Brown seems to confirm the point: The slaves of Virginia would have to fight their own war for emancipation.

In the end, abolitionists hit the slaveholders most directly through their influence on antislavery politics. This is not a comfortable position for Sinha. “Free soilism…was not abolition,” she makes clear; it was, in fact, “the lowest common denominator of antislavery, designed to appeal to the widest constituency.” Yet it mattered. In the 1850s, ironically enough, slaveholders had become ever more reliant on the federal government to protect their claims to property in other human beings, winning major concessions including the Fugitive Slave Act and the Dred Scott decision, which effectively nationalized slavery. The slaveholders’ success made national electoral politics a crucial arena of struggle. Garrison had never seen this as his fight; to him, abolition’s place lay not in party politics but “in agitation, to move the political center to the left.” Abolitionists had done a great deal to convince moderate white Northerners that the “Slave Power” was a looming threat to American democracy—as indeed it was. Whether outside party politics or on the left wing of the Republican Party, abolitionists functioned “as a political pressure group.” Thus, Sinha argues, when Lincoln won the presidency in 1860, Republicans reaped the harvest that abolitionists had sown: “The northern antislavery majority that elected Lincoln to the presidency was the product of at least three decades of arduous and persistent abolitionist work.” No doubt this is all true—but it’s a strikingly understated claim in causational terms. And it leaves a yawning gap between the abolition movement and slave emancipation as it was accomplished in the United States.

The brutal fact is that, notwithstanding years of principled abolitionist activism, it took war to make emancipation possible. What are the implications for the potential of democratic radicalism? It was Southern slaveholders’ rejection of the democratic process—their refusal to accept the results of the 1860 presidential election and their subsequent gamble on secession—that changed the balance of power and created the terrain on which the final struggle over slavery was waged. Sinha acknowledges that “the slaves who defected to Union army lines initiated the process of emancipation,” even as their abolitionist and Radical Republican allies played their customary roles, calling for immediate and uncompensated emancipation and black recruitment in the Union Army. But that kind of slave resistance falls far outside the boundaries of the abolition movement, even as Sinha defines it, and so she passes over the subject quickly. We know a lot about that war for emancipation now: how slaves took matters into their own hands at terrible personal cost, waging a war against their masters and their masters’ newly declared nation-state on farms and plantations inside the Confederacy, in their flight to Union-held territory, and through their service in the Union Army and Navy. We still have no body count for that civil war. This, of course, is the process that W.E.B. Du Bois called a “general strike” and others have cast as a massive slave rebellion. But whatever you call it, the slave’s cause was finally in the hands of the mass of the enslaved themselves.

Frederick Douglass once said that the history of black people may be traced like the blood of a wounded man in a crowd. This is no less true now—in the midst of another test of American democracy on the sadly predictable ground of African Americans’ rights to equality, justice, and human dignity—than when he said it in 1852. In 1861, when the Civil War started, nobody in the United States would have predicted that, within four years, slavery would be abolished completely and without compensation. It took a war to dislodge slaveholders and destroy the institution of slavery. It could not be accomplished by the regular workings of democratic politics—radical, progressive, or otherwise. As we Americans are finally forced to answer for an epidemic of violence, including state-sanctioned violence, continually directed at African Americans, how can we deny that our politics is failing us? Or that the burden of righting this wrong has been left, once again, mostly to those who suffer it.

Stephanie McCurry Stephanie McCurry, the R. Gordon Hoxie Professor of American History at Columbia University, is the author of Women’s War: Fighting and Surviving the American Civil War.

To submit a correction for our consideration, click here.

Slavery finally came to an end in the United States during the 1860s. But who should take credit for freeing the slaves? The slaves themselves or the Union Army that defeated the Confederacy in the US Civil War? Hannah McDermott tells us what she thinks…

Fugitive slaves in the Dismal Swamp, Virginia. David Edward Cronin, 1888. Many fugitive slaves joined the Union Army in the US Civil War.

In a letter to Horace Greeley in August 1862, President Abraham Lincoln declared that his ‘paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery’. [1] Yet by the end of the American Civil war the enslavement of blacks had been formally abolished thanks in part to legislation such as the Emancipation Proclamation, as well as the post-war 13th Amendment to the Constitution. In popular memory, the man responsible for these great changes to American society is Lincoln; remembered as the ‘Great Emancipator’ and depicted as physically breaking the shackles binding African Americans to their masters. Though it is true enough that the inauguration of this Illinois statesman and his Republican administration provided Southern slave owners with an excuse to push for secession and defend their property from what they claimed to be an imminent threat, Lincoln was very clear in his presidential campaign and at the outset of his presidential term that his aim was not to touch slavery where it already existed, but simply to prevent its expansion. Was the President, therefore, as integral to the demise of black enslavement as has been suggested?

If the role of Lincoln as the driving force is to be questioned, it follows to ask what other influences were at play. More recently, some historians have done just this. In the wake of the social and political upheaval of the later 20th century, the American academy has produced a ‘new social history’, of which has led to a separate branch of Civil War historiography looking to the role of the slaves themselves in securing their own freedom. Historians such as Ira Berlin have emphasized the grass-roots movement of black slaves during the war, and their personal fight for freedom through escaping to Union territory and challenging the status quo. However, it is difficult to view these historical people and events in complete isolation. Thus, in this essay, I will examine the actions of slaves in conjunction with that of the Union army and also the administration in order to illustrate how the process was more complex and multi-layered than simply one person, or one group, as the harbinger of emancipation.

Slaves and the Escape to Union Lines

Slaves were far from the passive and docile creatures that some pro-slavery activists liked to suggest. A steady trickle made the passage North even before the Civil War began, where their presence shaped the anti-slavery activities of white northern men. Frederick Douglass, for example, was a former slave who had managed to escape from his southern house of bondage in 1838. Douglass brought a unique perspective that would influence the abolition movement since he was able to express the hardships of enslaved blacks, as well as demonstrate the intelligence and capabilities of African Americans to northern audiences.

It was during the Civil War, however, that the number of slaves running away from their masters reached its peak and was largely based on the knowledge that refuge could be sought within the lines of the Union army. Prior to the Fugitive Slave Act, those who escaped to ‘free soil’, non-slaveholding regions, were considered to have self-emancipated; during the war, proximity to free soil was increased as the Union lines crept further and further south. [2]

From the outset of war, thousands of African Americans flooded Union camps, sometimes in family units, and left army generals wondering how they should respond. After entering Kentucky in the fall of 1861, General Alexander McDowell McCook appealed for guidance from his superior, General William T. Sherman, on how he should respond to the arrival of fugitive slaves. McCook worriedly declared to Sherman that ‘ten have come into my camp within as many hours’ and ‘from what they say, there will be a general stampeed [sic] of slaves from the other side of Green River.’ [3] General Ambrose E. Burnside faced a similar situation in March 1862, describing how the federally occupied city of New Bern, North Carolina, was ‘overrun with fugitives from surrounding towns and plantations’ and that the ‘negroes…seemed to be wild with excitement and delight.’ [4] Such encounters would continue throughout the war as slaves made the decision to leave behind their life of enslavement for the hope of a better life with the advancing ‘Yankees’.

The Union Army: Active and Passive Advocates of Emancipation

Though it is clear that slaves made the personal decision to runaway, it was one that was facilitated by the context of war. While there were exceptions to this, including stories of slaves found hiding in swamps only 100 feet from their master’s homes, most had a destination in mind when they fled. Archy Vaughn’s escape is a case in point. One spring evening in 1864, Archy Vaughn, a slave from a small town in Tennessee, made a potentially life-changing decision. As the sun went down, Vaughn stole an old mare and travelled to the ferry across the nearby Wolf River, hoping that he would be able to reach the federal lines he had heard were positioned at Laffayette Depot. Unfortunately for the Tennessean slave, luck was not on his side. Caught near the ferry, he was returned to his angry master, Bartlet Ciles, who decided that an appropriate form of punishment for such misbehavior was to castrate Vaughn and to cut off a piece of his left ear. [5] In spite of the barbaric outcome, that Vaughn was hoping to ‘get into federal lines’ is demonstrative of how many slaves departed plantations on the basis that they would be able to seek refuge within the lines of the Union army. [6]

Indeed, the role of the Union army was crucial to the shaping of the future of fugitive slaves. Though this took various shapes and forms, it is a contribution that makes it impossible to view the road to freedom as one that slaves traversed alone and unaided. Some generals took a pragmatic approach to the situation they faced when entering slave-holding territory. General Benjamin Butler and his ‘contraband’ policy are noteworthy in this instance as examples of the army capitalizing on the events of the war. In July 1861, General Butler wrote a report to the Secretary of War detailing his view on how runaway slaves should be treated by the Union army which would become known as Butler’s ‘contraband’ theory. Here he made an emphatic resolution, decreeing that in rebel states, ‘I would confiscate that which was used to oppose my arms, and take all the property, which constituted the wealth of that state, and furnished the means by which the war is prosecuted.’ [7] Hinting at the two-fold benefit of adding to the workforce of Union troops and damaging the rebellion’s foundation simultaneously, Butler’s theory that fugitive slaves were ‘contraband’ was the first to explicitly express the potential gains to be made from legitimizing the harboring of ex-slaves.

Other generals were more vocal of their hatred towards slavery, and more aggressive in the tactics they employed. One incident was General John C. Frémont’s proclamation of August 30, 1861, which placed the state of Missouri under martial law, decreed that all property of those bearing arms in rebellion would be confiscated, including slaves, and that confiscated slaves would subsequently be declared free. [8] Frémont’s proclamation at this stage in the war was provocative and quite blatantly breached official federal policy; slaves could be emancipated under martial law when they came into contact with Union lines, and this had certainly not been the case here. [9] Lincoln ordered that the general rescind the proclamation, but its initial impact was not lost, for it had signaled the possible direction that the focus of the conflict could be turned toward, and substantiated southern beliefs that the northern war aims were centered around an impetus to rid the nation of the evils of slavery.

Frémont was not alone in pushing the legal and political boundaries set by the administration, and similar occurrences repeated themselves throughout the war. Even when blocked by Lincoln, as in the case above, abolitionist Union officers were essential in the changing direction of the war. Whilst not all Union troops were politically motivated, the combination of those realizing the value of slaves in bolstering the war effort and those of an anti-slavery persuasion like General Frémont was an effective tool in aiding and sustaining the freedom of slaves across the United States.

The Republican Administration and Emancipation

In studying the response of the Union military it is easy to come to the conclusion that the federal government often lagged behind or was slow to respond to what was already happening within the Union army, or even that they were less supportive of the plight of the slaves during the war. Indeed Lincoln and his administration are often criticized on their attitude towards making the Civil War a war to free the slaves, particularly by historians who place the responsibility of slave emancipation on the efforts of the slaves themselves. Berlin describes the 1863 Emancipation Proclamation as ‘a document whose grand title promised so much but whose bland words delivered so little’, and further states that it freed not a single slave that had not been freed under the legislation passed by Congress the previous year in the Second Confiscation Act. [10] First of all, that the First and Second Confiscation Acts were the products of the administration should be noted. The Second, as referenced by Berlin, declared that any person who thereafter aided the rebellion would have their slaves set free. [11] Secondly, the notion that the Emancipation Proclamation was in essence no more than a grandly worded document without any backbone is false when it is understood how the proclamation’s inclusion of black conscription had wider repercussions for the Union military effort and the attainment of black freedom. Though examples of blacks serving in the military are visible before Lincoln’s proclamation, for instance Jim Lane’s 1st Kansas Colored Volunteer Infantry formed in 1862, the new federal policy made this a much more frequent occurrence. This is also to say nothing of the emotional and moral impact such a document made on the psyche of the African American community.

Though it can be conceded that the Emancipation Proclamation positively contributed to emancipation efforts, it would be wrong to claim as James McPherson does that Lincoln played ‘the central role’ in ending the institution of bondage. [12] The same is true for evaluations of subsequent abolitionist legislation, notably the Thirteenth Amendment. Oakes’ emphatic declaration that the amendment, which formally prohibited slavery across the United States, ‘irreversibly destroyed’ slavery is correct in highlighting the importance of an anti-slavery constitutional amendment but simultaneously overshadows the role played by non-political actors in the fight for freedom. [13] The movement of slaves towards federal lines and the protection they were then given is surely comparable to the effects of the Thirteenth Amendment, despite being described by Carwardine as ‘the only means of guaranteeing that African Americans be “forever free”.’ [14]

Instead, as this essay has demonstrated, the freeing of slaves during the Civil War is best understood as a multi-layered, interactive process. Slaves were not passive participators; they could and would act on the opportunities to leave behind a life of slavery for one of freedom. Though things might not always go to plan, as Archy Vaughn’s violent tale illustrates, the impetus to leave among enslaved African Americans was strong. Nevertheless, they did not free themselves. The action of slaves alone was not enough to ensure freedom, and the slaves themselves knew this. The decision to seek refuge with the federal army is indicative of how slaves predicated their choice to leave from the very beginning on the support of Union military power. Members of the federal forces were also not passive agents in the emancipation journey. While General Frémont, for example, may have identified the need to destroy slavery from the very beginning of the conflict, by the end of the war there was a shared sentiment among the Union forces that the use of ex-slaves in the fight against the South, menial tasks and armed battle included, was a vital component of the war effort. The federal administration realized this too; implementing policies that further aided and legitimized the support given by the army to slaves, as well as enhanced the contributions made by slaves to the achievement of Union victory. Slaves were freed, therefore, through the interaction of the mutually reinforcing interests of fugitive slaves and the Union war effort. It was this collaboration that enabled the mutually beneficial outcome in which the Confederacy was defeated at the hands of an emancipating Union vanguard.

Did you find this article fascinating? If so, tell the world. Share it, like it, or tweet about it by clicking on one of the buttons below…

1. To Horace Greeley, 22 August 1862 in Roy P. Basler (ed.), The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1953-1955) v, 389

2. James Oakes, Freedom National: the Destruction of Slavery in the United States, 1861-1865 (New York: London, 2013), pp. 194-96

3. Ira Berlin et al (eds.), Free At Last: A Documentary History of Slavery, Freedom, and the Civil War (New York, 1992), pp. 13-14

7. General Butler’s “Contrabands”, 30 July 1861 in Henry Steele Commager and Milton Cantor (eds.), Documents of American History, 10th edn (New York, 1988) i, 396-97

8. Frémont’s Proclamation on Slaves, 30 August 1861 in Commager and Cantor (eds.), Documents of American History, i, 397-98

9. Oakes, Freedom National, pp. 215

10. Berlin, ‘Who Freed the Slaves?’, pp. 27-29

11. Second Confiscation Act, 17 July 1862 in United States, Statutes At Large (Boston, 1863) XII, pp. 589-92

12. James McPherson, ‘Who Freed the Slaves?’ in Drawn with the Sword (New York: Oxford, 1996), pp. 207

13. Oakes, Freedom National, pp. xiv

Are you an expert on the USA?

1. What is the capital of the USA?

a) Ottawa b) Washington, D.C. c) New York

2. How many states are there in the USA?

3. What is the American flag called?

a) Union John b) Union Jack c) Stars and Stripes

4. When did Christopher Columbus discover America?

a) in 1492 b) in 1592 c) in 1392

5. How often do American people choose a new President?

a) every 5 years b) every 3 years c) every 4 years

6. What is the most expensive part of New York?

a) Long Island b) Manhattan c) Staten Island

7. What colour are the taxis in New York?

a) black b) yellow c) green

8. The building on the picture is ……..

a) The Capitol b) The Pentagon c) The White House.

9. If you go to New York, you will see ……….

a) Big Ben b) The Capitol c) The Empire State Building

10. The territory of the USA is washed by?

a) the Pacific ocean b) the Indian ocean c) Atlantic ocean d) Black Sea

e) Carribian Sea f) the Gulf of Mexico

11. What is the home of the President?

a) The Capitol b) The White House c) the House of Representatives

12.The first colonists started the tradition of

a) Halloween, b) Independence Day,

c) Thanksgiving Day, d) Memorial Day.

13.Who was the 1st President:

a) A.Lincoln b) Kennedy c) Johnson d) Washington.

14. What states are not connected to the other states?

a) Texas b) Kansas c)Alaska d) Oregon e)Hawai

15. The population of the USA is …

a) 350 million people

b)250 million people

c)450 million people

16. What river American called “the father of waters”?

a) Missouri b) Colorado c) Mississippi

17. What river formed the Grand Canyon?

a) Missouri b) Colorado c) Mississippi

18. The Constitution was written in…

a) Texas b) Philadelphia c)Alaska d) Oregon e)Hawaii

a) Three b) four c) five

a) Twenty-one b) twenty-six c)thirty-six

21. What President made slaves free?

a) G. Washington b) A. Lincoln c) G.Bush

22. Comment on this: “The USA: one nation, many different people.”

23. Who can declare the war? ______________________

24. What is the most popular food in America?_______________

25. Who is Commander in Chief?______________________

What 8 U.S. Presidents Owned Slaves During Their Presidency? [closed]

Want to improve this question? Add details and clarify the problem by editing this post.

I would like to know which U.S. Presidents owned slaves while in office. I think the list I put together on The Politicus is correct, but wanted to make sure.

1 Answer 1

Did he own slaves? Yes. Thomas Jefferson inherited many slaves. His wife brought a dowry of more than 100 slaves, and he purchased many more throughout his life. At some points he was one of the largest slave owners in Virginia. In 1790 Thomas Jefferson gave his newly married daughter and her husband 1000 acres of land and 25 slaves. (Miller) In 1798 Thomas Jefferson owned 141 slaves, many of them elderly. Two years later he owned 93. (Bigelow, P.537.) One of Thomas Jefferson’s slaves was Sally Hemings, allegedly the half-sister of his deceased wife. During Thomas Jefferson’s presidency a rumor appeared in print that she was his mistress. Thomas Jefferson denied this story, which was also passed on as Hemings family tradition. The youngest of Heming’s six children (and the only one whose paternity can be traced through DNA) definitely descended from the Jefferson line, either through Thomas Jefferson, his brother Randolph, or one of Randolph’s sons. Thomas Jefferson was in the vicinity of SH during each period of conception. (See Miller, P.148-176.) For a discussion of the DNA issue see: http://tinyurl.com/ckfkk2 and http://jeffersondna.com Thomas Jefferson freed one of Heming’s children and allowed another to run away unpursued. Both of them were light enough to successfully pass for White. (See Miller, P.165.) Thomas Jefferson freed five slaves in his will, all members of the Hemings family. Sally was not among them; Thomas Jefferson’s daughter Martha freed her years later. (See Miller, P.168.)

Did he own slaves? Yes. JM inherited a slave named Ralph. When he owned the farm Highland he owned 30 to 40 slaves. (James Monroe and Slavery.)

Did he own slaves? Yes. AJ bought his first slave, a young woman, in 1788.By 1794 his business included slave trading and he had purchased at least 16 slaves. (Remini, P.37, 55) In the 1820s Jackson owned about 160 slaves. (James, P.31) He did not free his slaves in his will.

Did he own slaves? Yes.

Did he own slaves? Yes. In 1832 he had fifteen slaves.

Тест по теме «США»

Are you an expert on Great Britain?

1. What is the capital of Great Britain?

a) Edinburgh b) Boston c) London

2. How many parts does Great Britain contain?

3. What is the English flag called?

a) Union Patric b) Union Jack c) Lines and Crosses

4. Who is the symbol of the typical Englishman?

a) John Bull b) John Bell c) St. Patric

5. What is the London underground called?

a) the tube b) the metro c) the subway

6. Who is the Head of State in Britain?

a) the Mayor b) the Queen c) the Prime Minister

7. What is the river in London?

a) Thames b) London c) Avon

8. What is the most expensive part of London?

a) West End b) East End c) the City

9. What colour are the taxis in London?

a) blue b) red c) black

10. The building in the picture is …

a) St.Paul`s Cathedral

b) The British Museum

c) The National Gallery

11. If you go to London, you will see …..

a) the White House

b) St.Paul`s Cathedral

12. English people say……

a) candies b) cookies c) sweets

13.What is the Home of the Queen?

a) Buckingham Palace b) the White House c) Westminster Abbey

14. What city did The Beatles from?

a) London b) Manchester c) Liverpool

15. They say the Loch Ness Monster lives in a lake in ……….

a) Scotland b) Wales c) Ireland

Are you an expert on the USA?

1. What is the capital of the USA?

a) Ottawa b) Washington, D.C. c) New York

2. How many states are there in the USA?

3. What is the American flag called?

a) Union John b) Union Jack c) Stars and Stripes

4. When did Christopher Columbus discover America?

a) in 1492 b) in 1592 c) in 1392

5. How often do American people choose a new President?

a) every 5 years b) every 3 years c) every 4 years

6. What is the most expensive part of New York?

a) Long Island b) Manhattan c) Staten Island

7. What colour are the taxis in New York?

a) black b) yellow c) green

8. The building on the picture is ……..

a) The Capitol b) The Pentagon c) The White House

.

9. If you go to New York, you will see ……….

a) Big Ben b) The Capitol c) The Empire State Building

10. The territory of the USA is washed by?

a) the Pacific ocean b) the Indian ocean c) Atlantic ocean d) Black Sea

e) Carribian Sea f) the Gulf of Mexico

11. What is the home of the President?

a) The Capitol b) The White House c) the House of Representatives

The first colonists started the tradition of

a) Halloween, b) Independence Day,

c) Thanksgiving Day, d) Memorial Day.

Who was the 1 st President:

A.Lincoln b) Kennedy c) Johnson d) Washington.

What states are not connected to the other states?

Texas b) Kansas c)Alaska d) Oregon e)Hawai

The population of the USA is …

350 million people

250 million people

450 million people

What river American called “the father of waters”?

Missouri b) Colorado c) Mississippi

What river formed the Grand Canyon?

Missouri b) Colorado c) Mississippi

The Constitution was written in…

Texas b) Philadelphia c)Alaska d) Oregon e)Hawaii

Three b) four c) five

Twenty-one b) twenty-six c)thirty-six

What President made slaves free?

G. Washington b) A. Lincoln c) G.Bush

Comment on this:

“ The USA: one nation, many different people.”

Who can declare the war? ______________________

What is the most popular food in America?_______________

Who is Commander in Chief?______________________

выберите один из тектов и переведите его на русский язык)

The United States of America stretches from the Atlantic Ocean across North America and far into the Pacific.

Because of such a huge size of the country the climate differs from one part of the country to another. The coldest climate is in the northern part, where there is heavy snow in winter and the temperature may go down to 40 degrees below zero. The south has a subtropical climate, with temperature as high as 49 degrees in summer.

America was founded by Columbus in 1492.

Columbus was mistaken in thinking he had reached India. There is still a great deal of confusion about the East and the West. As Columbus discovered, if you go west long enough you find yourself in the east and vice versa. In the New World most of the eastern half of the country is called the Middle West although it is known as the East by those who live in the Far West.

Americans eat a lot. They have three meals a day: breakfast, lunch and dinner.

Most of Americans don’t eat at home but prefer to go to restaurants. They can choose from many kind of restaurants. There is a great number of ethnic restaurants in the United States. Italian, Chinese and Mexican food is very popular. An American institution is the fast food restaurant, which is very convenient but not very healthy.

The eagle became the national emblem of the country in 1782. It has an olive branch (a symbol of peace) and arrows (a symbol of strength). You can see the eagle on the back of a dollar bill.

This monument is the symbol of American democracy. It stands on Liberty Island in New York. It is one of the first things people see when they arrive in New York by sea. This National Monument was a present from France to the USA. France gave the statue to America in 1886 as a symbol of friendship. Liberty carries the torch of freedom — in her right hand. In her left hand she is holding a tablet with the inscription «July 4, 1776» — American Independence Day.