Why what how концепция

Why what how концепция

Why what how концепция

Секреты успеха: ответь на 6 ключевых вопросов

Чтобы успешно управлять операциями, достаточно ответить на 5 W вопросов: Who? Who? Where? When? HoW? – Кто? Что? Когда, Где? Когда? Как?

Итак, если хочешь добиться стабильного успеха в бизнесе, всегда помни про 6W корпоративного роста и применяй этот принцип на практике.

Помнишь старый анекдот по автомеханика, к которому обращались за помощью, когда все другие механики не могли устранить неполадку? Он слушал мотор в течение нескольких минут и потом ударял в некоторую стратегическую точку, после чего мотор, ко всеобщему изумлению, начинал великолепно работать. Механик после этого предъявлял хозяину автомобиля счет на 400 долларов. Тот просил объяснить за что. Механик уточнял: 1 доллар за мое время и 399 долларов за знание, где ударить.

Лидер нужен там, где нужно вводить перемены. Если перемены не нужны можно ограничиться менеджментом. Поскольку в современной быстро меняющейся экономике перемены происходят непрерывно, быстро и непредсказуемо, в связи с чем роль лидеров резко возрастает. >>>

Why, How, What (The Golden Circle Model)

Developed by Ugur Erman

Contents

Abstract

One of the key things for a project manager, in regard to doing projects, is to establish a strong vision. By establishing the purpose of the project, the vision enables the team members of the projects to collaborate, it gives them a direction and it gives the team members a great opportunity to develop and grow. By having a purpose of a project, it becomes possible to answer why the project is being done in the first place. [1]

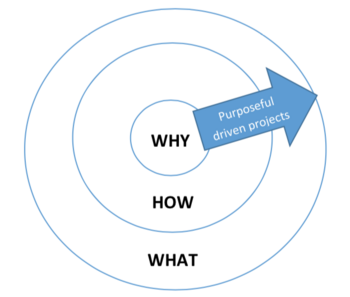

According to Best Management Practice, a vision is «a picture of a better future». [2] There are several ways to establish a vision of a project and one of them is by asking: WHY? Simon Sinek, a British-American author and marketing consultant is the person who has developed The Golden Circle Model. This model consists of the questions WHY, HOW and WHAT. According to Sinek, every organization and leader know WHAT they are doing, some know HOW they do it and very few know WHY they are doing it. And by WHY (according to Sinek) very few organizations and leaders know the purpose of the things they are doing. As a result, Sinek finds that the way unsuccessful organizations and leaders think is from outside in (from WHAT to WHY). In contrast, the more inspiring and successful organizations and leaders think from inside out (from WHY to WHAT). [1] [3]

In the following of this article, several aspects of the model will be treated, such as

Big Idea

In this section of the article the Golden Circle Model will be explained and the points that the model itself states will also be included in this section.

The Golden Circle model is a model that can be used in a variety of ways. It can be used by organizations, by people every day and by leaders among others. The leader can be the CEO of a company or it can be a project manager among others. The model is designed by Simon Sinek and it consists of 3 parts: WHY, HOW and WHAT.

According to Sinek, everyone knows WHAT they are doing, some people know HOW they do it, but very few people know WHY they do it. The question «WHY?» shall not be answered with something as making money, since that is a result of the things that are being done. However by asking WHY, the purpose of the project and its cause and belief shall be defined. [4]

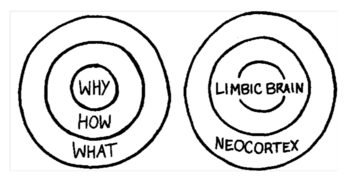

The Golden Circle Model is not just a model that help leaders and project managers to communicate to successfully drive a project. The model is closely related to the human biology and especially the human brain. The WHAT part of the model that a leader uses corresponds with the neocortex, a part of the brain that is responsible for analytical thought among others. However, both HOW and especially WHY corresponds with the limbic brain which is responsible for feelings such as loyalty. When leaders communicate from outside in, they are able to connect with their co-workers in terms of information. The downside of this way of communicating a vision is that it will not drive behavior. On the other hand, when leaders communicate the vision from inside out, it triggers the part of the human brain that is responsible for decision making and it will thus drive the behavior of the participants of the project. [4]

Clarity, Discipline and Consistency

In his model, Sinek explains something he calls the Clarity of WHY, the Discipline of HOW and the Consistency of WHAT. He believes that everything starts with clarity, meaning that the inspiring leaders need to know WHY the WHATs are being done. They also need to clearly articulate the WHY to their co-workers since the co-workers need to know WHY they have to be part of a project and WHY they have to passionately work for the project.

With the discipline of HOW, Sinek believes that the HOWs are the values and principles that will help leaders and the team members to successfully bring the purpose of the project to life. The discipline of HOW is important when things seem to go wrong. When a leader is able to hold his or her team members accountable to the values and principles, it will inspire and enhance team members to team work and work more passionately.

Example 1

In the late nineteenth century the new technology was to create an airplane. The most well-known people in this regard are Samuel Pierpont Langley and the Wright brothers. The Wright brothers are the ones who are actually credited for inventing the world’s first successful airplane in 1903. [5] [6] Langley graduated from high school and worked as a professor of mathematics at a university. Langley was a well-connected man and he was well funded. He was able to assemble a great team around him to create the world’s first successful airplane. The team members included well-known engineers and the team had access to good resources in terms of materials. On the other hand, the Wright brothers did attend high school for three years, but they did not get their diploma. Their team included people who did not graduate college and even people who did not graduate high school. Unlike Langley, they were not well funded. The only source of money they had access to, was the money they made during the time they worked at their bicycle shop. [5] [6]

Example 2

One of the most influential persons in the twentieth century is Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., who in 1963 in Washington D.C. gave his «I Have a Dream» speech as the leader of the civil rights movement. The speech was given in order to address the inequality and segregation that America was facing in the 1960s. At that time 250,000 civil rights supporters showed up and the speech itself was and still is considered as a defining moment of the civil rights movement. [7]

One might ask why Dr. King was so successful with his speech. Surely there were other people at that time who were thinking the same as Dr. King and surely were there other people who knew WHAT needed to be done as Dr. King knew. The way Dr. King was able to distinguish himself from others was through his clarity of WHY. He was able to clearly articulate WHY things needed to change and it inspired other people to believe the same as he did. Dr. King was not necessarily able to inspire people in terms of HOW the WHATs should be done, but he surely did inspire them in terms of WHY things needed to change. The people who showed up heard his beliefs, they were touched by them and they were incorporating the ideas into their own lives. [3]

Applications

As it has been stated earlier, the Golden Circle Model can be applied by leaders on different levels. The leader can among others be the CEO of a company or it can be the project manager of a project team. No matter what level the leader is on, it is important to inspire people to believe the belief and purpose of the ideas a leader might have in order to create behavior.

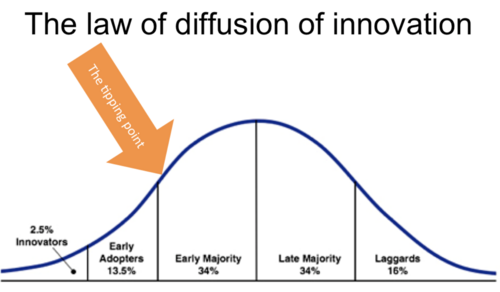

In this regard the Golden Circle Model is related to the Law of Diffusion of Innovation, a theory described by Everett Rogers which tells why, how and at what rate ideas spread. [9] According to the theory, the population can be divided into 5 categories: 2.5 % Innovators, 13.5 % Early Adopters, 34 % Early Majority, 34 % Late Majority and 16 % Laggards. Basically, the innovators are the part of the population who are willing to pursue and come up with a new idea quickly and they are the ones who think differently from most people. The early adopters are somehow similar to the innovators, but they generally do not come up with new ideas, but they welcome new ideas. The early adopters are followed by the early majority and the late majority which are somewhat similar, but the late majority people are normally more skeptical to new ideas compared to the early majority. The early majority people are the ones who feel safer when other people have pursued an idea before them. The laggards on the other hand are people who are more comfortable with how things are at the concerned time. They appreciate traditions more than new ideas. [9] [4]

The leader should aim for the so-called tipping point. This is a point where the spread of the WHY happens at a rapid pace and where most people accept and believe the idea. According to the Diffusion of Innovations, this will happen when approximately 15-18 percent of the people that the leader is trying to inspire are inspired. This percentage of the people should be furthest to the left on the curve in figure 3. This percentage of the inspired people are the ones who believe the WHY and to purposefully drive a project or an idea, the leader must start with WHY. [4]

Limitations

Although the Golden Circle Model seems to be a model that can be widely used among leaders, it is not a perfect tool. Simon Sinek states that organizations and leaders who have a clear WHY and who think from inside out are successful. However, one might ask whether this is true or not. Although Sinek makes several points and gives several examples of companies and people who have been thinking from inside out, there is no empirical data backing up his statements. Even though it seems to make sense that a clear WHY can drive behavior, it is not proved that a company or a leader who start with WHAT or HOW has not been able to drive projects or a company successfully.

As it is mentioned above, the statements from Simon Sinek are not backed up by empirical data and he is the only person who speaks about the model. It is important to critically evaluate some of the statements he makes about the model, but especially the relationship between the model and the human brain. Even though it seems to make sense that different parts of the brain trigger different things, it is to be noted that the brain is a complex system. Therefore, it might not be that easy to say what part of the brain drives behavior and what part of the brain is responsible for gathering information, since it might be a complex combination of different parts of the brain that, for instance, are responsible for behavior.

Annotated bibliography

This book is written by Simon Sinek himself. In this book, different aspects of the Golden Circle Model are treated. There is a blend of explanation of the theory of the Golden Circle Model with lots of examples. Sinek is quite often using Apple as an example in order to show and tell the reader of the book how Apple has differentiated themselves by starting with WHY. The book does not only cover the model in regard to how leaders should inspire people. Readers can also find a section of the book where it is explained how the model can represent the structure of a company or an organization.

In this book, different aspects of managing programs are covered. In regard to this article, there is a small section about the vision perspective, where the reader can get information about what a vision is and what a good vision should include. Additionally, readers can get information from this book about different program management principles, risk management, leadership and stakeholder engagement.

This document is the standards on project management. The standards provide a guidance on project management. These standards include several definitions related to projects and project management. The chapters of this document are split into 4 parts: Scope, terms and definitions, project management concepts and project management processes. One thing that the reader cannot directly find information about in these standards is vision and what a vision should include. The vision part is only covered in these standards in terms of how organizations establish a strategy based on several things including the vision.

Что, как и зачем: вопросы о проекте, на которые должен уметь отвечать предприниматель

Мнение австралийского журналиста

Австралийский предприниматель и журналист Джон Вестенберг написал в блоге на Medium заметку о позиционировании новых бизнес-проектов. Он рассуждает о том, что многие предприниматели склонны описывать свои продукты более сложными словами, чем следует. В то же время, указывает автор, не все создатели стартапов умеют внятно объяснить, что представляет собой их проект, как работает и для чего нужен.

«Умнейшие люди мира не прибегают к старым понятиям, чтобы объяснять новые. Возможно, я преувеличиваю, но я действительно так считаю. Я понял это, когда стал много встречаться и разговаривать с создателями стартапов. Я постоянно получаю письма от людей, которые хотят, чтобы я написал об их стартапе или поделился мнением о нём. Многие пытаются описывать свои идеи, смешивая их с уже существующими. Это как набившая оскомину конструкция «Uber для

X»», — пишет Вестенберг.

В пример он приводит историю компании, которая делает хорошие электрические скутеры, но не пытается говорить об этом прямо, а позиционирует себя как «Tesla в мире скутеров». «Подобное позиционирование может лишь ограничить вас и обязательно ограничит. Если вы определяете свой продукт чужими терминами, вы не сообщаете важнейшую информацию. Вы только говорите, что скопировали что-то. Это довольно бессмысленный подход. Он ничего не говорит о ценности продукта», — рассуждает автор.

Другой ошибочный подход к позиционированию, на который он обращает внимание, заключается в неуместном употреблении характерных слов: «Я видел питчи, в которых интернет вещей, биткоин, блокчейн и искусственный интеллект упоминались в одном предложении. Это вызывало желание отвергнуть технологии и стать чёртовым отшельником».

По мнению Вестенберга, чтобы избежать подобных проблем, у предпринимателя должны быть простые и чёткие ответы на вопросы «что», «как» и «зачем». «Мой приятель занимается венчурными инвестициями здесь в Австралии и знакомится с большим количеством разных заявок. Некоторые из них хороши, но большинство тяжело воспринимать. Дело в том, что создатели проектов не могут внятно объяснить, что они делают. Он заставляет их возвращаться к первому слайду презентации и описать в нескольких предложениях суть. Ему нужны ответы на три вопроса. И если у них не получается ответить, он не тратит на них время», — рассказывает автор.

Он подчёркивает, что при описании проекта нужно использовать простые собственные слова, а не модные слова: «Если вы делаете текстовый редактор с минималистским дизайном, то так и говорите. Не называйте это рабочей средой для создания контента без отвлекающих факторов».

При ответе на вопрос «как?» Вестенберг рекомендует объяснить, как возник проект, в чём заключается методология, есть ли какие-то готовые разработки и вкладывал ли создатель собственные средства.

«Вероятно, более важно объяснить, почему вы занимаетесь именно этим. Вы проводили тесты перед началом работы над проектом? Изучали рынок? Уверены, что будет спрос? Решает ли продукт какую-либо проблему? Чем он лучше конкурентов, и достаточно ли лучше? На эти вопросы будет трудно ответить. Это факт. Но предпринимательство — это не пешая прогулка, и совершенно точно это не занятие какой-то случайной и необъяснимой ерундой. Так не получится».

Вестенберг пишет, что умение отвечать на приведённые им вопросы помогает заинтересовать людей. Кроме того, оно помогает самому предпринимателю лучше понять своё занятие и более точно оценить качество своих идей: «Просто придумать что-то не сложно, сложно придумать что-то стоящее, у чего есть назначение и конкретные адресаты. Не ответив на эти вопросы, вы не сможете понять, сработает ли ваша идея».

«Если бы я был добрым человеком, я бы сказал, что у таких предпринимателей проблемы с выражением мыслей. Но я не добрый, я гадкий. Так что я думаю, что они понятия не имеют о том, что, как и зачем они делают, и просто заимствуют какие-то вещи у других успешных продуктов или приложений, сваливают их в кучу и ждут денег», — пишет Вестенберг.

Он полагает, что люди зачастую опасаются, что их слова прозвучат слишком просто. «Поэтому, когда мы не до конца уверены в своих идеях или увлечениях, мы пытаемся думать о них как о сложных, запутанных вещах, чтобы они казались состоятельнее. Так появляются маркетинговые планы на 50 страниц там, где можно обойтись пятью. Но простота хороша. Простые ответы хороши. Простота не отнимает лишнее время и не вводит в заблуждение. Я скорее заинтересуюсь и напишу о среднем продукте, у которого хорошее описание, чем о выдающемся продукте, который не понимаю».

eugeneyan

Here’s a story from the early days of Amazon Web Services: Before writing any code, engineers spent 18 months contemplating and writing documents on how best to serve the customer. Amazon believes this is the fastest way to work—thinking deeply about what the customer needs before executing on that rigorously refined vision.

Similarly, as a data scientist, though I solve problems via code, a lot of the work happens before writing any code. Such work takes the form of thinking and/via writing documents. This is especially so in Amazon, which is famous for its writing culture.

This post (and the next) answers the most voted-for question on the topic poll:

How to write design documents for data science/machine learning projects?

I’ll start by sharing three documents I’ve written: one-pagers, design documents, and after action reviews. Then, I’ll reveal the framework I use to structure most of my writing, including this post. In the next post, we’ll discuss design docs.

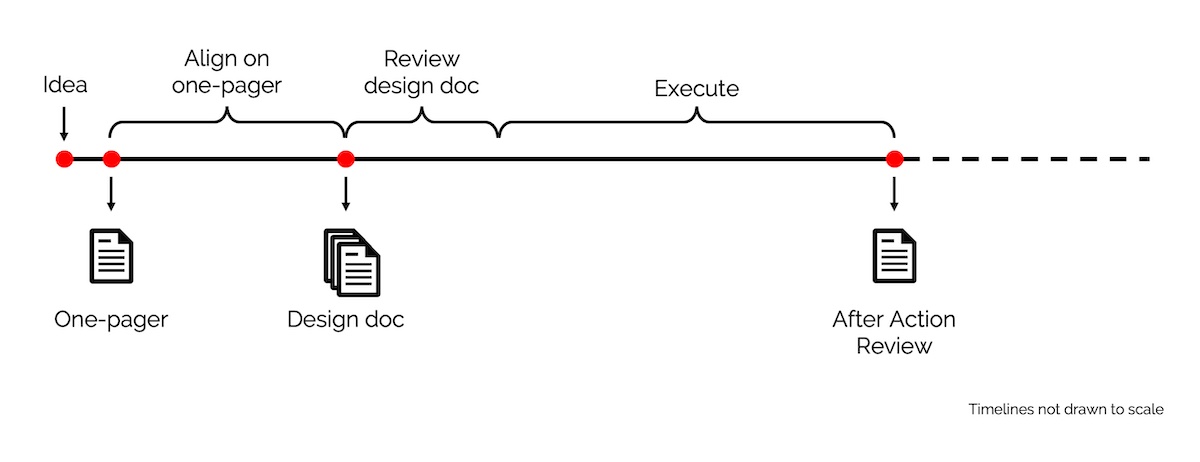

One-pagers, design docs, after-action reviews

I usually write three types of documents when building/operating a system. The first two help to get alignment and feedback; the last is used to reflect—all three assist with thinking deeply and improving outcomes.

The three types of documents written during a project

One-pagers: I use these to achieve alignment with business/product stakeholders. Also used as background memos for quarterly/yearly prioritization. In a single page, they should allow readers to quickly understand the problem, expected outcomes, proposed solution, and high-level approach. Extremely useful to reference when you’re deep in the weeds of a project, or encounter scope creep.

Design docs: I use these to get feedback from fellow scientists and engineers. They help identify design issues early in the process. Furthermore, you can iterate on design docs more rapidly than on systems, especially if said systems are already in production. It usually covers methodology and system design, and includes experiment results and technical benchmarks (if available).

Design docs are more commonly seen in engineering projects; not so much for data science/machine learning. Nonetheless, I’ve found it invaluable for building better ML systems and products.

After-action reviews: I use these to reflect after shipping a project, or after a major error. If it’s a project review, we cover what went well (and not so well), follow-up actions, and how to do better next time. It’s like a scrum retrospective, except with more time to think and written as a document. The knowledge can then be shared with other teams.

If it’s an error review (e.g., the system goes down), we diagnose the root cause and identify follow-up actions to prevent reoccurrence. Nowhere do we blame individuals. The intent is to discuss what we can do better and share the (sometimes painful) lessons with the greater organization. Amazon calls these Correction of Errors; here’s how it looks like.

Writing framework: Why, What, How, (Who)

The Why-What-How framework is so simple that it sounds like a reading/writing lesson for first graders. Nonetheless, it guides most, if not all, of my work documents. My writing on this site also follows it (the other format being lists like this and this).

Why: Start by explaining Why the document is important. This is often framed around the problem or opportunity we want to address, and the expected benefits. We might also answer the question of Why now?

Think of this as the hook for your document. After reading the Why, readers should feel compelled to blaze through the rest of your doc (and hopefully commit to your proposal). In resource-strapped environments (e.g., start-ups), this section convinces decision-makers to invest resources into your idea.

Thus, it’s critical that—after reading this section—your audience understands the problem and context. Describe it simply in their terms: customer benefits, business gains, productivity improvements. Contrast the two Whys below; which is better suited for a business audience?

“We need to procure GPU clusters for distributed training of SOTA deep learning models that will improve [email protected] by 20%.”

“We need to invest in infrastructure to improve customer recommendations, with an expected conversion and revenue uplift of 5%.”

The first one might be a tad exaggerated, but I’ve seen Whys that start like that. 🤦♂️ It’s a great way to lose the audience from the get-go.

What: After the audience is convinced we should solve the problem, share what a good solution looks like. What are the expected outcomes and ways to measure them?

One way to frame What is via measures of success and constraints. Measures of success define what a good (or bad) solution looks like; constraints define what solutions can (and cannot) do. Together, they enable readers to evaluate and decide on proposals, make trade-offs, and provide feedback.

Another way of framing What is via requirements. Business requirements specify the expected customer experience, uplift to business metrics (success measures), and budget (constraints). They might also be framed as product or functional requirements. Technical requirements specify throughput, latency, security, privacy, etc., usually as constraints.

How: Finally, explain How you’ll achieve the Why and What. This includes methodology, high-level design, tech decisions, etc. It’s also useful to add how you’re not implementing it (i.e., out of scope).

The depth of this section depends on the document. For one-pagers, it could be a paragraph or two on deliverables, with details in the appendix. For design docs, you may want to include a system context diagram, tech decisions (e.g., centralized vs. distributed, EC2 vs. EMR vs. SageMaker), offline experiment results (e.g., hit rate, nDCG), and benchmarks (e.g., throughput, latency, instance count).

Having a solid Why and What provides context and makes this section easier to write. It also makes it easier for readers to evaluate and give feedback on your idea. Conversely, poorly articulated intent and requirements make it difficult to spot a good solution even when it’s in front of us.

(Who): While writing docs, we should keep our audience in mind. Although Who may not show up as a section in the doc, it’ll influence how it turns out (topics, depth, language).

A document for business leaders will (and should!) look very different from a document for engineers. Different audiences will focus on different aspects: customer pain points, business outcomes, ROI vs. technical requirements, design choices, API specifications.

Writing with your Who in mind makes for more productive discussions and feedback. We don’t ask business leaders for feedback on infra choices, and we don’t ask devops engineers for guidance on business strategy.

How to use the framework to structure your docs

Here are some examples of using Why-What-How to structure a one-pager, design doc, after-action review, and my writing on this site.

One-pager example

Why: Our data science team (in an e-commerce company) is challenged to help customers discover products easier. Senior leaders hypothesize that better product discovery will improve customer engagement and business outcomes.

What: First-order metrics are engagement (e.g., CTR) and revenue (e.g., conversion, revenue per session). Second-order metrics include app usage (e.g., daily active users) and retention (e.g., monthly active users). Constraints are set via a budget and timeline.

How: The team considered several online (e.g., search, recommendations) and offline (e.g., targeted emails, push notifications) approaches. Their analysis showed the majority of customer activity occurs on product pages. Thus, an item-to-item (i2i) recommender—on product pages—is hypothesized to yield the greatest ROI.

Appendix: Breakdown of inbound channels and site activity, overview of the various approaches, detailed explanation on recommendation systems.

Design document example

Why: Currently, our product pages lack a way for users to discover similar products. To address this, we are building an i2i recommender to improve product discoverability and customer engagement.

What: Business requirements are similar to those specified in the one-pager, albeit with greater detail. We collaborated with the web and mobile app teams to define technical requirements such as throughput (> 1,000 requests per second), latency (

After-action review example

Context: During a peak sales day (11/11), the i2i recommender was not visible on product pages for a period of time. This was discovered by category managers inspecting their products’ discounts.

Why (5 Whys): The spike in traffic led to increased latency (>150ms) when serving recommendations. The increased latency led to the recommender widget timing out—and not being shown—on product pages. While autoscaling was enabled, it hit the instance quotas and could not scale beyond that. Though we conducted load tests at 3x normal traffic, these were insufficient as peak traffic was 30x normal traffic. In addition, it was not discovered earlier because our alarms didn’t account for results not being displayed.

How: We will take these follow-up actions to prevent a repeated incident and detect similar issues earlier. These are their respective owners.

Appendix: Timeline of incident, overall learnings and recommendations.

Personal writing example

Why: Why is writing documents important? Share anecdote. Mention it’s highly voted-for.

What: What documents do I write? Share some examples.

How: Explain the Why-What-How approach and share examples of how I use it.

Writing docs is expensive, but cheap

Writing documents cost money. They take time to write, review, and iterate on—this is time that could have been spent on implementation.

Nonetheless, writing is a cheap way to ensure we solve the right problems in the right way. They save money by helping teams avoid rabbit holes or building systems that aren’t used. They also help align stakeholders, improve initial ideas, and scale knowledge.

If the problem is ambiguous, the proposed solution contentious, the effort required high (> 3-6 months), and/or consensus is required across multiple teams, starting with a document will save effort in the medium to long term.

So before you start your next project, write a document using Why-What-How. Here’s more detail about one-pagers (and other things I do before starting a project).

While starting AWS, before writing any code, engineers spent 18 months writing documents on how best to serve customers.

Similarly, before I build anything, I write docs. Here, I’ll share three docs I write and reveal the framework that structures themhttps://t.co/6hNt4F1Qwz

Thanks to Yang Xinyi for reading drafts of this.

The Why, What, and How of Management Innovation

Over the past century, breakthroughs such as brand management and the divisionalized organization structure have created more sustained competitive advantage than anything that came out of a lab or focus group. Here’s how you can make your company a serial management innovator.

Over the past century, breakthroughs such as brand management and the divisionalized organization structure have created more sustained competitive advantage than anything that came out of a lab or focus group. Here’s how you can make your company a serial management innovator.

The Idea in Brief

Yet most companies focus their innovation efforts on developing new offerings or achieving operational efficiencies—gains competitors quickly copy. To stay ahead of rivals, you must become a serial management innovator, systematically seeking breakthroughs in how your company executes crucial managerial processes.

The keys to serial management innovation? Tackle a big problem—as General Motors did by inventing the divisional structure to bring order to its sprawling family of companies. Search for radical management principles—as Visa’s founders did when they envisioned self-organization—and created the first non-stock, for-profit membership enterprise. Challenge conventional management beliefs, which Toyota did by deciding that frontline employees—not top executives—make the best process innovators.

You can’t afford to let rivals beat you to the next great management breakthrough. By becoming a serial management innovator, you cross new performance thresholds—and sustain your competitive edge.

The Idea in Practice

To become a serial management innovator:

Commit to a Big Problem

The bigger the problem you’re facing, the bigger the innovation opportunity. To identify meaty problems, ask:

What tough trade-offs do we never get right? For example, does obsessive pursuit of short-term earnings undermine our willingness to invest in new ideas? Is our organization growing less agile while pursuing size and scale advantages? What other “either/or’s” can we turn into “and’s”?

What is our organization bad at? For instance, do we have trouble changing before we’re forced to? Unleashing first-line employees’ imaginations? Creating an inspiring work environment? Ensuring that bureaucracy doesn’t smother innovation? Imagine a “can’t do” that you can turn into a “can do.”

What challenges will the future hold for us? For example, what are the ramifications of escalating consumer power? Near-instant commoditization of products? Ultra low-cost rivals?

Challenge Your Management Orthodoxies

Conventional wisdom often obstructs innovation. Ask your colleagues what they believe about a critical management issue. Identify beliefs held in common. Then ask if these beliefs inhibit your ability to tackle the big problem you’ve identified. If so, consider alternative assumptions that could open the door to fresh insights. Example:

In your firm, common beliefs about change might include “change must start at the top.” But this belief may be toxic to your organization. Why? It makes employees assume that they can’t influence the company’s business model or strategy. Thus they withhold their full engagement and passion—essential ingredients for continual organizational renewal. A more helpful alternative belief? “Change must start everywhere in our organization.”

Exploit the Power of Analogy

Identify decidedly unconventional organizations, and look for the practices they apply that might help you solve your problem. Example:

If you seek ideas for funding ordinary employees’ glimmer-in-the-eye projects, study Bangladesh’s Grameen Bank. It makes micro-loans to poor people with no collateral requirement and little paperwork. Borrowers—which by 2004 numbered more than 4 million—use the funds to start small businesses that benefit themselves and their communities. Ask: How can we make it equally easy for our employees to get capital to fund an idea?

Click here for printable worksheets to test your management innovation.

Are you a management innovator? Have you discovered entirely new ways to organize, lead, coordinate, or motivate? Is your company a management pioneer? Has it invented novel approaches to management that are the envy of its competitors?

Does it matter? It sure does. Innovation in management principles and processes can create long-lasting advantage and produce dramatic shifts in competitive position. Over the past 100 years, management innovation, more than any other kind of innovation, has allowed companies to cross new performance thresholds.

Yet strangely enough, few companies have a well-honed process for continuous management innovation. Most businesses have a formal methodology for product innovation, and many have R&D groups that explore the frontiers of science. Virtually every organization on the planet has in recent years worked systematically to reinvent its business processes for the sake of speed and efficiency. How odd, then, that so few companies apply a similar degree of diligence to the kind of innovation that matters most: management innovation.

Why is management innovation so vital? What makes it different from other kinds of innovation? How can you and your company become blue-ribbon management innovators? Let’s start with the why.

Why Management Innovation Matters

General Electric. DuPont. Procter & Gamble. Visa. Linux. What makes them stand out? Great products? Yes. Great people? Sure. Great leaders? Usually. But if you dig deeper, you will find another, more fundamental reason for their success: management innovation.

As these examples show, a management breakthrough can deliver a potent advantage to the innovating company and produce a seismic shift in industry leadership. Technology and product innovation, by comparison, tend to deliver small-caliber advantages.

A management innovation creates long-lasting advantage when it meets one or more of three conditions: The innovation is based on a novel principle that challenges management orthodoxy; it is systemic, encompassing a range of processes and methods; and it is part of an ongoing program of invention, where progress compounds over time. Three brief cases illustrate the ways in which management innovation can create enduring success.

Harnessing employee intellect at Toyota.

Why has it taken America’s automobile manufacturers so long to narrow their efficiency gap with Toyota? In large part, because it took Detroit more than 20 years to ferret out the radical management principle at the heart of Toyota’s capacity for relentless improvement. Unlike its Western rivals, Toyota has long believed that first-line employees can be more than cogs in a soulless manufacturing machine; they can be problem solvers, innovators, and change agents. While American companies relied on staff experts to come up with process improvements, Toyota gave every employee the skills, the tools, and the permission to solve problems as they arose and to head off new problems before they occurred. The result: Year after year, Toyota has been able to get more out of its people than its competitors have been able to get out of theirs. Such is the power of management orthodoxy that it was only after American carmakers had exhausted every other explanation for Toyota’s success—an undervalued yen, a docile workforce, Japanese culture, superior automation—that they were finally able to admit that Toyota’s real advantage was its ability to harness the intellect of “ordinary” employees. As this example illustrates, management orthodoxies are often so deeply ingrained in executive thinking that they are nearly invisible and are so devoutly held that they are practically unassailable. The more unconventional the principle underlying a management innovation, the longer it will take competitors to respond. In some cases, the head-scratching can go on for decades.

Building a community at Whole Foods.

Growing great leaders at GE.

Sometimes a company can create a sizable management advantage simply by being persistent. No company in the world is better at developing great managers than GE, even though many businesses have imitated elements of the company’s leadership development system, such as its dedicated training facility in Crotonville, New York, or its 360-degree feedback process. GE’s leadership advantage isn’t the product of a single breakthrough but the result of a long-standing and unflagging commitment to improving the quality of the company’s management stock—a commitment that regularly spawns new management approaches and methods.

Not every management innovation creates competitive advantage, however. Innovation in whatever form follows a power law: For every truly radical idea that delivers a big dollop of competitive advantage, there will be dozens of other ideas that prove to be less valuable. But that’s no excuse not to innovate. Innovation is always a numbers game; the more of it you do, the better your chances of reaping a fat payoff.

What Is Management Innovation?

A management innovation can be defined as a marked departure from traditional management principles, processes, and practices or a departure from customary organizational forms that significantly alters the way the work of management is performed. Put simply, management innovation changes how managers do what they do. And what do managers do? Typically, managerial work includes

In a big organization, the only way to change how managers work is to reinvent the processes that govern that work. Management processes such as strategic planning, capital budgeting, project management, hiring and promotion, employee assessment, executive development, internal communications, and knowledge management are the gears that turn management principles into everyday practices. They establish the recipes and rituals that govern the work of managers. While operational innovation focuses on a company’s business processes (procurement, logistics, customer support, and so on), management innovation targets a company’s management processes.

The Elements of Management Innovation

In most companies, management innovation is ad hoc and incremental. A systematic process for producing bold management breakthroughs must include

Commitment to a big management problem

Novel principles that illuminate new approaches

A deconstruction of management orthodoxies

Analogies from atypical organizations that redefine what’s possible

Whirlpool, the world’s largest manufacturer of household appliances, is one company that has turned itself into a serial management innovator. In 1999, frustrated by chronically low levels of brand loyalty among appliance buyers, Dave Whitwam, Whirlpool’s then chairman and CEO, issued a challenge to his leadership team: Turn Whirlpool into a font of rule-breaking, customer-pleasing innovation. From the outset, it was clear that Whitwam’s goal of “innovation from everyone, everywhere” would require major changes in the company’s management processes, which had been designed to drive operational efficiency. Appointed Whirlpool’s first innovation czar, Nancy Snyder, a corporate vice president, rallied her colleagues around what would become a five-year quest to reinvent the company’s management processes. Key changes included

How to Become a Management Innovator

I have yet to meet a senior executive who claims that his or her company has a praiseworthy process for management innovation. What’s missing, it seems, is a practical methodology. As with other types of innovation, the biggest challenge is generating truly novel ideas. While there is no sausage crank for innovation, it’s possible to increase the odds of a “Eureka!” moment by assembling the right ingredients. Some of the essential components are

There is no sausage crank for innovation, but it’s possible to increase the odds of a “Eureka!” moment by assembling the right ingredients.

Chunky problems. Fresh principles. Unorthodox thinking. Wisdom from the fringe. These multipliers of human creativity are as pivotal to management innovation as they are to every other kind of innovation. If you want to turn your company into a perpetual management innovator, here’s how you can get started.

Commit to a big problem.

The bigger the problem, the bigger the opportunity for innovation. While big problems don’t always produce big breakthroughs, little problems never do. Nearly 80 years ago, General Motors invented the divisionalized organization structure in response to a seemingly intractable problem: how to bring order to the sprawling family of companies that had been assembled by William C. Durant, GM’s first president. Durant’s successor, Pierre Du Pont, who took charge in 1920, asked one of his senior associates, Alfred P. Sloan, Jr., to help simplify GM’s dysfunctional empire. Sloan’s solution: Establish a central executive committee charged with setting policy and exercising financial control, and set up operating divisions organized by products and brands, with responsibility for day-to-day operations. Thanks to this management innovation, GM was able to take advantage of its scale and scope. In 1931, with Sloan at the helm, GM finally overtook Ford to become the world’s largest carmaker.

It takes fortitude and perseverance, as well as imagination, to solve big problems. These qualities are most abundant when a problem is not only important but also inspiring. Frederick Winslow Taylor, arguably the most important management innovator of the twentieth century, is usually portrayed as a hard-nosed engineer, intent on mechanizing work and pushing employees to the max. Stern he may have been, but Taylor’s single-minded devotion to efficiency stemmed from his conviction that it was iniquitous to waste an hour of human labor when a task could be redesigned to be performed with less effort.

This passion for multiplying the impact of human endeavor shines through in Taylor’s introduction to his 1911 opus, The Principles of Scientific Management: “We can see and feel the waste of material things. Awkward, inefficient, or ill-directed movements of men, however, leave nothing visible or tangible behind them. Their appreciation calls for an act of memory, an effort of the imagination. And for this reason, even though our daily loss from this source is greater than from our waste of material things, the one has stirred us deeply, while the other has moved us but little.”

To maximize the chances of a management breakthrough, you need to start with a problem that is both consequential and soul stirring. If you don’t have such a problem in mind, here are three leading questions that will stimulate your imagination.

First, what are the tough trade-offs that your company never seems to get right? Management innovation is often driven by the desire to transcend such trade-offs, which can appear to be irreconcilable. Open source development, for example, encompasses two antithetical ideas: radical decentralization and disciplined, large-scale project management. Perhaps you feel that the obsessive pursuit of short-term earnings undermines your company’s willingness to invest in new ideas. Maybe you believe that your organization has become less and less agile as it has pursued the advantages of size and scale. Your challenge is to find an opportunity to turn an “either/or” into an “and.”

Second, what are big organizations bad at? This question should produce a long list of incompetencies. Big companies aren’t very good at changing before they have to or responding to nimble upstarts. Most fail miserably when it comes to unleashing the imagination of first-line employees, creating an inspiring work environment, or ensuring that the blanket of bureaucracy doesn’t smother the flames of innovation. Push yourself to imagine a company can’t-do that you and your colleagues could turn into a can-do.

Third, what are the emerging challenges the future has in store for your company? Try to imagine them: An ever-accelerating pace of change. Rapidly escalating customer power. Near instant commoditization of products and services. Ultra-low-cost competitors. A new generation of consumers that is hype resistant and deeply cynical about big business. These discontinuities will demand management innovation as well as business model innovation. If you scan the horizon, you’re sure to see a tomorrow problem that your company should start tackling today.

Search for new principles.

Any problem that is pervasive, persistent, or unprecedented is unlikely to be solved with hand-me-down principles. The pursuit of human liberty required America’s founders to embrace a new principle: representational democracy. More recently, scientists eager to understand the subatomic world have been forced to abandon the certainties of Newtonian physics for the more ambiguous principles of quantum mechanics. It’s no different with management innovation: Novel problems demand novel principles.

That was certainly true for Visa. By 1968, America’s credit card industry had splintered into a number of incompatible, bank-specific franchising systems. The ensuing chaos threatened the viability of the fledgling business. It was at a meeting to discuss this knotty problem that Dee Hock, a 38-year-old banker from Seattle, volunteered to lead an effort to resolve the industry’s biggest conundrum: how to build a system that would allow banks to cooperate in credit card branding and billing while still competing fiercely for consumers. Faced with this unprecedented challenge, Hock’s small team spent months coming up with a set of radical principles to guide their work:

These principles owed more to Hock’s fascination with Jeffersonian democracy and biological systems than to any management textbook. After two years of inventing, designing, and testing, Hock’s team brought forth Visa, the world’s first nonstock, for-profit membership organization—or, as Hock put it, an “organization whose product was coordination.”

It’s hard to know if a management principle is really new unless you know which ones are strictly vintage. Modern management practice is based on a set of principles whose origins date back a century or more: specialization, standardization, planning and control, hierarchy, and the primacy of extrinsic rewards. Generations of managers have mined these principles for competitive advantage, and they have much to show for their efforts. But after decades of digging, the chance of discovering a gleaming nugget of new management wisdom in these well-explored caverns is remote. Your challenge is to uncover unconventional principles that open up new seams of management innovation. Your quest should begin with two simple questions: What things exhibit the attributes or capabilities that you’d like to build into your organization? And what is it that imbues those exemplars with their enviable qualities?

Let’s suppose your goal is to make your company as nimble as change itself. You know that in a world of accelerating change, continuous strategic renewal is the only insurance against irrelevance. Moreover, you realize that all those management principles you’ve inherited from the Industrial Age make your company less, rather than more, adaptable. Specialization, for all its benefits, limits the kind of cross-boundary learning that generates breakthrough ideas. The quest for greater standardization often leads to an unhealthy affection for conformance; the new and the wacky are seen as dangerous deviations from the norm. Elaborate planning-and-control systems lull executives into believing the environment is more predictable than it is. A disproportionate emphasis on monetary rewards leads managers to discount the power of volunteerism and self-organization as mechanisms for aligning individual effort. Deference to hierarchy and positional power tends to reinforce outmoded belief systems.

So where do you look to find the design principles for building a highly adaptable organization? You look to systems that have demonstrated their adaptability over decades, centuries, even aeons.

For more than 4 billion years, life has evolved at least as fast as its environment. That’s quite a track record. Nature inoculates itself against the risks of environmental change by constantly creating new genetic material through sexual recombination and mutation. This bubbling fountain of genetic innovation is the key to nature’s capacity for adaptation: The greater the diversity of the gene pool, the more likely it is that at least a few organisms will be able to survive in a dramatically altered landscape. Variety is one essential principle of adaptability.

Markets, too, are adaptable. Over the past 50 years, the New York Stock Exchange has outperformed virtually every one of its member companies. Competition is a hallmark of both markets and evolutionary biology. On the NYSE, companies compete to attract funds, and investors are free to place their bets as they see fit. Decision making is highly distributed, and investors are mostly unsentimental. As a result, markets are very efficient at reallocating resources from opportunities that are less promising to those that are more so. In most companies, however, there are rigidities that tend to perpetuate historical patterns of resource allocation. Executives, eager to defend their power, hoard capital and talent even when those resources could be better used elsewhere. Legacy programs seldom have to compete for resources against a plethora of exciting alternatives. The net result is that companies tend to overinvest in the past and underinvest in the future. Hence, competition and allocation flexibility are also important design principles if the goal is to build a highly adaptive organization.

Constitutional democracies rank high on any scale of evolvability. In a democracy, there is no monopoly on political action. Social campaigners, interest groups, think tanks, and ordinary citizens all have the chance to shape the legislative agenda and influence government policy. Whereas change in an autocratic regime comes in violent convulsions, change in a democracy is the product of many small, relatively gentle adjustments. If the goal is continuous, trauma-free renewal, most large corporations are still too much like monarchies and too little like democracies. With political power concentrated in the hands of a few dozen senior executives, and with little latitude for local experimentation, it’s no wonder that big companies so often find themselves caught behind the change curve. To reduce the costs of change in your organization, you must embrace the principles of devolution and activism.

These management principles—variety, competition, allocation flexibility, devolution, and activism—stand in marked contrast to those we’ve inherited from the early decades of the Industrial Revolution. That doesn’t make the old principles wrong, but they are inadequate if the goal is continuous, preemptive strategic renewal.

Whatever big management challenge you choose to tackle, let it guide your search for new principles. For example, maybe your goal is to build a company that can prevail against the steadily strengthening forces of commoditization—a problem that certainly demands management innovation. It isn’t just products and services that are rapidly becoming commodities today but also broad business capabilities like low-cost manufacturing, customer support, product design, and human resource planning. Around the world, companies are outsourcing and offshoring business processes to vendors that provide more or less the same service to a number of competing firms. Businesses are collaborating across big chunks of the value chain, forming partnerships and joining industrywide consortia to share risks and reduce capital outlays. Add to this a worldwide army of consultants that has been working overtime to transfer best practices from the fast to the slow and from the smart to the not so clever. As once-distinctive capabilities become commodities, companies will have to wring a whole lot of competitive differentiation out of their ever-shrinking wedge of the overall business system.

Twelve Innovations That Shaped Modern Management

Surprisingly, scholars have paid little attention to the process of management innovation. Seeking to correct this oversight, I have been working with Julian Birkinshaw and Michael Mol, both of the London Business School, to better understand the genesis of the twentieth century’s most important management innovations. First we identified 175 significant management innovations from 1900 to 2000. To whittle this list down to the most important advances, we evaluated each innovation along three dimensions: Was it a marked departure from previous management practices? Did it confer a competitive advantage on the pioneering company or companies? And could it be found in some form in organizations today? In light of these criteria, here are a dozen of the most noteworthy innovations.

1. Scientific management (time and motion studies)

2. Cost accounting and variance analysis

3. The commercial research laboratory (the industrialization of science)

4. ROI analysis and capital budgeting

5. Brand management

6. Large-scale project management

7. Divisionalization

8. Leadership development

9. Industry consortia (multicompany collaborative structures)

10. Radical decentralization (self-organization)

11. Formalized strategic analysis

12. Employee-driven problem solving

Important innovations that didn’t quite make this list include Skunk Works, account management, business process reengineering, and employee stock ownership plans. There are more recent innovations that appear quite promising, such as knowledge management, open source development, and internal markets, but it’s too early to assess their lasting impact on the practice of management.

Here’s the rub: It’s tough to build eye-popping differentiation out of lower-order human capabilities like obedience, diligence, and raw intelligence—things that are themselves becoming global commodities, available for next to nothing in places like Guangzhou, Bangalore, and Manila. To beat back the forces of commoditization, a company must be able to deliver the kind of unique customer value that can only be created by employees who bring a full measure of their initiative, imagination, and zeal to work every day. You can glimpse those higher-order capabilities in Apple’s sleek and sexy iPods, in IKEA’s cheap and cheerful furniture, in Porsche’s iconic sports cars, and in Pixar’s magical movies. The problem is, there’s little room in bureaucratic organizations for passion, ingenuity, and self-direction. The machinery of bureaucracy was invented in an age when human beings were seen as little more than semiprogrammable robots. Bureaucracy puts an upper limit on what individuals are allowed to bring to their jobs. If you want to build an organization that unshackles the human spirit, you’re going to need some decidedly unbureaucratic management principles.

If you want to build an organization that unshackles the human spirit, you’re going to need some decidedly unbureaucratic management principles.

Where do you find organizations in which people give all of themselves? You might start with Habitat for Humanity, which has built more than 150,000 homes for low-income families since 1976. Talk to some of the folks who’ve given up a weekend to pound nails and hang drywall. Share a beer with a few of the part-time hackers who have churned out millions of lines of code for the Linux operating system. Or consider all those volunteers who’ve helped make Wikipedia the world’s largest encyclopedia, with more than 1.8 million articles. Each of these organizations is more of a community than a hierarchy. People are drawn to a community by a sense of shared purpose, not by economic need. In a community, the opportunity to contribute isn’t bounded by narrow job descriptions. Control is more peer based than boss based. Emotional satisfaction, rather than financial gain, drives commitment. For all those reasons, communities are amplifiers of human capability.

Whole Foods, you will remember, long ago embraced the notion of community as an overarching management principle. The company’s stores, sparkling temples of guilt-free gastronomy, are about as unlike the average Kroger or Safeway as one could imagine. That’s the kind of differentiation you get when your management system encourages team members to bring all their wonderful human qualities to work—and when your competitors’ management systems don’t.

Deconstruct your management orthodoxies.

To fully appreciate the power of a new management principle, you must loosen the grip that precedent has on your imagination. While some of what you believe may be scientific certainty, much of it isn’t. Painful as it is to admit, a lot of what passes for management wisdom is unquestioned dogma masquerading as unquestionable truth.

How do you uncover management orthodoxy? Pull together a group of colleagues, and ask them what they believe about some critical management issue like change, leadership, or employee engagement. Once everyone’s beliefs are out on the table, identify those that are held in common. For example, if the issue is strategic change, you may find that most of your colleagues believe that

Empirically, these beliefs seem true enough, but as a management innovator, you must be able to distinguish between what is apparently true and what is eternally true. Yes, big change initiatives like GE’s Six Sigma program typically require the support of an impassioned CEO. Yes, right-angle shifts in strategic direction, like Kodak’s embrace of all things digital, are usually precipitated by an earnings meltdown. And yes, just about every story of corporate renewal is a turnaround epic with the new CEO cast as corporate savior. But is this the only way the world can work? Why, you should ask, does it take a crisis to provoke deep change? For the simple reason that in most companies, a few senior executives have the first and last word on shifts in strategic direction. Hence, a tradition-bound management team, unwilling to surrender yesterday’s certainties, can hold hostage an entire organization’s capacity to embrace the future. So while it is true that it usually takes a crisis to motivate deep change, that isn’t some law of nature; it’s merely an artifact of a top-heavy distribution of political power.

It usually takes a crisis to motivate deep change. But that isn’t some law of nature; it’s merely an artifact of a top-heavy distribution of power.

As a management innovator, you must subject every management belief to two questions. First, is the belief toxic to the ultimate goal you’re trying to achieve? Second, can you imagine an alternative to the reality the belief reflects? Take the typical assumption that the CEO is responsible for setting strategy. While this seems a reasonable point of view, it may lull employees into believing that they can do little to influence their company’s strategic direction or to reshape its business model—that they are the implementers, rather than the creators, of strategy. Yet, if the goal is to accelerate the pace of strategic renewal or to fully engage the imagination and passion of every employee, a CEO-centric view of strategy formulation is unhelpful at best and dangerous at worst.

Is there any reason to believe we can challenge this well-entrenched orthodoxy? Sure. Look at Google. Its top team doesn’t spend a lot of time trying to cook up grand strategies. Instead, it works to create an environment that spawns lots of “Googlettes”: small, grassroots projects that may one day grow into valuable new products and services. Google looks for recruits who have off-the-wall hobbies and unconventional interests—people who aren’t afraid to defy conventional wisdom—and, after it hires them, encourages them to spend up to 20% of their time working on whatever they feel will benefit Google’s users and advertisers. The company organizes much of its workforce into small, project-focused teams with only a modicum of supervision (one Google manager claimed to have 160 direct reports!) but with a lot of lateral communication and intramural competition. Its developers post their most-promising inventions on the Google Labs Web site, which gives adventurous users the chance to evaluate new concepts.

Few companies have worked as systematically as Google to broadly distribute the responsibility for strategic innovation. Its experience suggests that the conventional view of the CEO as the strategist in chief is just that: a convention. It’s not entirely wrong, but it’s a long way from being totally right. And when you hold other management maxims up to the bright light of critical examination, you are likely to find that many are equally flimsy. As old certainties crumble, the space for management innovation grows.

Exploit the power of analogy.

Servant leadership. The power of diversity. Self-organizing teams. These are newfangled notions, right? Wrong. Each of those important management ideas was foreshadowed in the writings of Mary Parker Follett, a management innovator whose life was bracketed by the American Civil War and the Great Depression. Consider a few of the farsighted management tenets in Follett’s book, Creative Experience, first published in 1924:

Follett’s heretical insights didn’t come from a survey of industrial best practice; they grew out of her experience in building and running Boston-based community associations. Vested with little formal authority and faced with the challenge of melding the competing interests of several fractious constituencies, Follett developed a set of beliefs about management that were starkly different from those that prevailed at the time. As is so often the case with innovation, a unique vantage point yielded unique insights.

If your goal is to escape the straitjacket of conventional management thinking, it helps to study the practices of organizations that are decidedly unconventional. With a bit of digging, you can unearth a menagerie of exotic organizational life-forms that look nothing like the usual doyens of best practice. Imagine, for instance, an enterprise that has more than 2 million members and only one criterion for joining: You have to want in. It has virtually no hierarchy, yet it spans the globe. Its world headquarters has fewer than 100 employees. Local leaders are elected, not appointed. There are neither plans nor budgets. There is a corporate mission but no detailed strategy or operating plans. Yet this organization delivers a complex service to millions of people and has thrived for more than 60 years. What is it? Alcoholics Anonymous. AA consists of thousands of small, self-organizing groups. Two simple admonitions inspire AA’s members: “Get sober” and “Help others.” Organizational cohesion comes from adherence to the 12-step program and observance of the 12 traditions that are outlined in the group’s operating principles. AA may have been around for decades, but it is still in the management vanguard.

Just how far can you push autonomy and self-direction in your company? Is there some set of simple rules that could simultaneously unleash local initiative and provide focus and discipline? Is there some meritorious goal that could spur volunteerism?

The example of Bangladesh’s Grameen Bank is another spur to inventive management thinking. The bank’s mission is to turn the poorest of the poor into entrepreneurs. To that end, it makes microloans to five-person syndicates with no requirement for collateral and little in the way of paperwork. Borrowers use the funds to start small businesses such as basket weaving, embroidery, transportation services, and poultry breeding. Ninety-five percent of the bank’s loans go to women, who have proven to be both creditworthy borrowers and astute businesspeople. Microcredit gives these women the chance to improve their families’ well-being and their own social standing. As of 2004, Grameen Bank had provided funds to more than 4 million borrowers. Isn’t it a bit odd that a desperately poor woman in a developing country has an easier time getting capital to fund an idea than a first-level associate in your company? If Grameen Bank can make millions of unsecured loans to individuals who have no banking history, shouldn’t your company be able to find a way to fund the glimmer-in-the-eye projects of ordinary employees? Now, that would be a management innovation!

A final analogy: As I’m writing this, William Hill, one of the UK’s leading bookmakers, is offering odds of 3.5:1 “off” on Tiger Woods in the 2006 Masters golf tournament. That is, Woods is estimated to be three-and-a-half more times likely to lose than to win. The odds on Phil Mickelson are rather longer at 10:1, while Sergio Garcia’s chances are rated at 26:1. The odds are probability estimates based on two kinds of data: the expert judgment of odds compilers and the collective opinion of sports-mad punters laying down their bets. Having set an initial price on a particular outcome, bookmakers adjust the odds over time as people place additional bets and the wisdom of the crowd becomes more apparent.

What’s the lesson for would-be management innovators? Every day, companies bet millions of dollars on risky initiatives: new products, new ad campaigns, new factories, big mergers, and so on. History suggests that many projects will fail to deliver their expected returns. Is there a way of guarding against the hubris and optimism that so often inflate investment expectations? One potential solution would be to create a market for judgment that harnesses the wisdom of a broad cross section of employees to set the odds on a project’s anticipated returns. An executive sponsor would set the initial odds for a project to achieve a particular rate of return within a specific time frame. Let’s say those odds get set at 5:1 “on,” meaning that the sponsor believes there’s a five-to-one chance that the project will deliver the anticipated return. Employees would then be able to bet for or against that outcome. If many more employees bet against the project than for it, the sponsor would have to readjust the odds. While a CEO could still back a long-shot project, the transparency of the process would reduce the chance of investment decisions being overly influenced by the sponsor’s power or personal persuasiveness. Who would have thought that bookies could inspire management innovation? Your challenge is to hunt down equally unlikely analogies that suggest new ways of tackling thorny management problems.

Get the Rubber on the Road

OK, you’re inspired! You have some great ideas for management innovation. To turn your precedent-busting theories into reality, you need to understand exactly how your company’s existing management processes exacerbate that big problem you’re hoping to solve. Start by answering the following questions for each relevant management process:

After documenting the details of each process, assemble a cross section of interested parties such as the process owner, regular participants, and anyone else who might have a relevant point of view. Ask them to assess the process in terms of its impact on the management challenge you’re seeking to address. For example, if the goal is to accelerate your company’s pace of strategic renewal, you may conclude that the existing capital approval process demands an unreasonably high degree of certainty about future returns even when the initial investment is very small. This frustrates the flexible reallocation of resources to new opportunities. You may find that your company’s strategic planning process is elitist in that it gives a disproportionate share of voice to senior executives at the expense of new ideas from people on the front lines. This severely limits the variety of strategic options your company considers. Perhaps the hiring process overweights technical competence and industry experience compared with lateral thinking and creativity. Other human resource processes may be too focused on ensuring compliance and not focused enough on emancipating employee initiative. The net result? Your company is earning a paltry return on its investment in human capital. A deep and systematic review of your firm’s management processes will reveal opportunities to reinvent them in ways that further your bold objectives.

Of course, you are unlikely to get permission to reinvent a core management process at one go, however toxic it may be. Like renowned social psychologist Elton Mayo, who some 80 years ago conducted human behavior experiments in the Hawthorne Works of the Western Electric Company, you’ll have to design low-risk trials that let you test your management innovations without disrupting the entire organization. That may mean designing a simulation, where you run a critical strategic issue through a novel decision-making process to see whether it produces a different decision. It may mean operating a new management process in parallel with the old process for a time. Maybe you’ll want to post your innovation on an internal Web site and invite people from across the company to evaluate and comment on your ideas before they’re put into practice. The goal is to build a portfolio of bold new management experiments that has the power to lift the performance of your company ever higher above its peers. • • •

Most organizations around the world have been built on the same handful of time-tested management principles. Given that, it’s hardly surprising that core management processes like capital budgeting, strategic planning, and leadership development vary only slightly from one company to another. Although we sometimes affix the “dinosaur” label to chronically underperforming companies, the truth is that every organization has more than a bit of dinosaur DNA lurking in its management processes and practices. In the corporate ecosphere, there are little dinosaurs and big dinosaurs, rambunctious toddlers and tottering oldsters. But no company can escape the fact that with each passing year, the present is becoming a less reliable guide to the future. While there is much in the current management genome that will undoubtedly be valuable in the years ahead, there is also a great deal that will need to change. So far, management in the twenty-first century isn’t much different from management in the twentieth century. Therein lies the opportunity. You can wait for a competitor to stumble upon the next great management breakthrough, or you can become a management innovator right now. In a world swarming with new management challenges, you’ll need to be even more inventive and less tradition bound than all those management pioneers who came before you. If you succeed, your legacy of management innovation will be no less illustrious than theirs.