How do executive orders work

How do executive orders work

How Executive Orders Work

By: Dave Roos | Updated: Jul 11, 2022

On February 19, 1942, two months after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066. In this one-page decree, the president used his authority as the commander-in-chief to authorize the U.S. military to «exclude» 122,000 Japanese Americans — more than half of them U.S. citizens — from their homes and businesses and relocate them to isolated and desolate internment camps [source: Our Documents]. A month later, Congress passed Public Law 503, making it a federal offense to disobey the president’s executive order.

An executive order, also known as a proclamation, is a directive handed down directly from a president or governor (the executive branch of government) without input from the legislative or judicial branches. Executive orders can only be given to federal or state agencies, not to citizens, although citizens are indirectly affected by them.

Executive orders have been used by every American president since George Washington to lead the nation through times of war, to respond to natural disasters and economic crises, to encourage or discourage regulation by federal agencies, to promote civil rights, or in the case of the Japanese internment camps, to revoke civil rights. Executive orders can also be used by governors to direct state agencies, often in response to emergencies, but also to promote the governor’s own regulatory and social policies.

There is no specific mention of executive orders in the U.S. Constitution. Instead, presidents argue that the power to make executive orders is implied in the following statements contained in Article II of the Constitution:

Governors use similar interpretations of their state constitutions to justify the legality of executive orders.

Critics of executive orders argue that these unilateral decrees undermine our trusted system of checks and balances, giving undue authority to the executive branch. For that reason, executive orders are considered a form of «executive legislation» [source: Contrubis]. In recent years, presidents have wielded executive orders as political weapons to push through controversial policies or regulations without Congressional or judicial oversight. Executive orders can be overruled by the courts or nullified by legislators after the fact, but until then they carry the full weight of federal and state law [source: Contrubis].

To better understand the controversial and colorful history of executive orders in the United States, let’s start at the beginning, with George Washington himself.

Executive Order

Contents

An executive order is an official directive from the U.S. president to federal agencies that often have much the same power of a law. Throughout history, executive orders have been one way that the power of the president and the executive branch of government has expanded—to degrees that are sometimes controversial.

What is an Executive Order?

The U.S. Constitution does not directly define or give the president authority to issue presidential actions, which include executive orders, presidential memoranda and proclamations.

Instead, this implied and accepted power derives from Article II of the Constitution, which states that as head of the executive branch and commander in chief of the armed forces, the president “shall take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed.”

With an executive order, the president instructs the government how to work within the parameters already set by Congress and the Constitution. In effect, this allows the president to push through policy changes without going through Congress.

By issuing an executive order, the president does not create a new law or appropriate any funds from the U.S. Treasury; only Congress has the power to do both of these things.

How an Executive Order is Carried Out

Any executive order must identify whether the order is based on the powers given to the president by the U.S. Constitution or delegated to him by Congress.

Provided the order has a solid basis either in the Constitution, and the powers it vests in the president—as head of state, head of the executive branch and commander in chief of the nation’s armed forces—or in laws passed by Congress, an executive order has the force of law.

After the president issues an executive order, that order is recorded in the Federal Register and is considered binding, which means it can be enforced in the same way as if Congress had enacted it as law.

Checks and Balances on Executive Orders

Just like laws, executive orders are subject to legal review, and the Supreme Court or lower federal courts can nullify, or cancel, an executive order if they determine it is unconstitutional.

Similarly, Congress can revoke an executive order by passing new legislation. These are examples of the checks and balances built into the system of U.S. government to ensure that no one branch—executive, legislative or judicial—becomes too powerful.

Recommended for you

8 Fascinating Facts About Ancient Roman Medicine

What Caused Ancient Egypt’s Decline?

The 6 Earliest Human Civilizations

One prominent example of this dynamic occurred in 1952, after Harry Truman issued an executive order directing his secretary of commerce to seize control of the country’s steel mills during the Korean War.

But in its ruling in Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer later that year, the Supreme Court ruled that Truman’s order violated the due process clause of the Constitution, and that the president had not been given statutory authority by Congress to seize private property.

Executive Orders Throughout History

Virtually every president since George Washington has used the executive order in different ways during their administrations.

Washington’s first order, in June 1789, directed the heads of executive departments to submit reports about their operations. Over the years, presidents have typically issued executive orders and other actions to set holidays for federal workers, regulate civil service, designate public lands as Indian reservations or national parks and organize federal disaster assistance efforts, among other uses.

William Henry Harrison, who died after one month in office, is the only president not to issue a single executive order; Franklin D. Roosevelt, the only president to serve more than two terms, signed by far the most executive orders (3,721), many of which established key parts of his sweeping New Deal reforms.

Executive orders have also been used to assert presidential war powers, starting with the Civil War and continuing throughout all subsequent wars. During the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln controversially used executive orders to suspend habeas corpus in 1861 and to enact his Emancipation Proclamation in 1863.

And during World War II, FDR notoriously issued an executive order mandating the internment of Japanese Americans in 1942.

Several presidents have used executive orders to enforce civil rights legislation in the face of state or local resistance. In 1948, Truman issued an executive order desegregating the nation’s armed forces, while Dwight D. Eisenhower used an order to send federal troops to integrate public schools in Little Rock, Arkansas, in 1957.

Trump Executive Orders

Between 1789 and 1907, U.S. presidents issued a combined total of approximately 2,400 executive orders. Since 1908, when the orders were first numbered chronologically, presidents have issued more than 13,700 executive orders, reflecting the expansion of presidential power over the years.

New presidents often sign a number of executive orders and other actions in the opening weeks of their administration, in order to direct the federal agencies they’re taking over.

Recent presidents have taken this practice to new heights: In January 2017, Donald Trump set a new record for the number of executive actions issued by a new president in his first week, with 14 (one more than the 13 issued by his immediate predecessor, Barack Obama, in January 2009), including six executive orders. President Joe Biden surpassed that record during his first two weeks in office, signing over 30 executive orders.

Sources

Executive Orders, The Oxford Guide to the United States Government.

Executive Orders 101: Constitution Daily.

Executive Orders: Issuance, Modification and Revocation, Congressional Research Service.

Truman vs. Steel Industry, 1952, Time.

Executive Orders, The American Presidency Project.

What is an executive order? And how do President Trump’s stack up? Washington Post.

How Does a Presidential Executive Order Work?

On January 20, 2021, President Joe Biden was sworn into office around midday and, by the time the sun was setting over the White House, he was already hard at work in the Oval Office, where he signed 15 executive orders. By January 29, President Biden’s total stood at 22 executive orders — plus 10 presidential memos and four proclamations. According to The American President Project, this is more than his most recent predecessors.

No matter the president, executive orders remain a somewhat contentious topic. Not only do they set a precedent in terms of presidential power, but these directives can be used to help an administration spotlight the key tenets of its agenda. With this in mind, let’s take a look at the history of executive orders in the United States and how the Biden administration has implemented them thus far.

What Is an Executive Order?

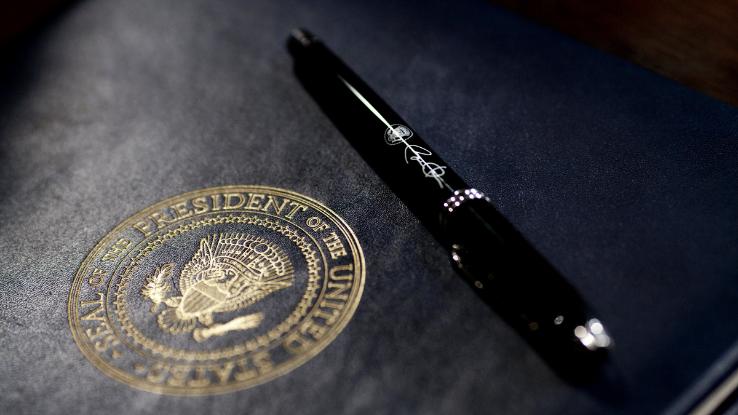

So, what exactly is an executive order? To put it simply, it’s a signed, written and published directive, issued by the President of the United States, that manages operations of the federal government. The actual document is broken into five parts: the heading, the title, the introduction, the body of the order and the signature. Additionally, instead of a name, each order is assigned a number.

Executive orders are usually designed to perform one of several functions. For example, it is common for such directives to address governmental management issues, particularly within the executive branch itself or other federal agencies. It is also possible for executive orders to aid the president in living up to constitutional requirements or duties. Nonetheless, the president must ensure that every component of the order is both legal and constitutional. Additionally, the president has the power to change or retract an order issued during their presidency, and there is no time constraint for doing so. Similarly, succeeding presidents can either keep pre-existing orders, revoke them or issue new orders superseding old ones.

Although they’re often the most high profile, executive orders aren’t the only presidential documents at the leader’s disposal. There are also proclamations, which “communicate information on holidays, commemorations, federal observances and trade,” and administrative orders, which encompass memos, letters, notices and other administrative messages (via the American Bar Association). However, despite their differences, all three of these document types are published in the Federal Register, the journal of the federal government that’s meant to inform the general public of daily goings-on.

How Is Presidential Executive Order Power Checked?

The most contentious aspect of executive orders is that they are treated like “instant laws.” Although executive orders have the force of law, they aren’t technically legislation, which means Congress doesn’t need to approve them. Although an article from Quartz notes that “the authority to issue these executive actions isn’t outlined in the Constitution, meaning they can be tough to define,” executive orders have been deemed completely constitutional since George Washington’s time in office.

In fact, Article Two of the U.S. Constitution grants the president the authority to use their discretion when it comes to enforcing the law or managing the executive branch and its resources. So, even though it’s legal, how is this presidential power checked? On the Congressional side, overturning an ill-received executive order isn’t easy; instead, Congress often passes legislation that defunds executive orders its members aren’t fond of, or else renders these orders difficult to execute. In fact, as mentioned above, only a sitting president has the power to overturn an executive order. Like legislation, executive orders are, however, subject to judicial review.

In fact, the Supreme Court has struck down such directives in the past. In 1952, President Harry Truman’s Executive Order 10340 came under fire when the president, fearing a steelworker strike, ordered his secretary of commerce to seize control of a majority of the country’s steel mills. In the end, the Supreme Court determined that the president lacked the “constitutional or statutory power to seize private property.” Where does the Court stand on other contentious directives? Well, the Court allowed President Ronald Reagan’s series of orders surrounding the Iranian Hostage Crisis to stand — and, more recently, did not choose to hear a suit filed against President Barack Obama for an executive order related to the implementation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA).

President Biden’s Use of Executive Orders So Far

According to the American Bar Association, every American president has issued at least one executive order during their presidency, though many in modern history have issued hundreds over the course of their terms in office. As mentioned above, executive orders are numbered consecutively and, at the end of January 2021, President Biden signed order number 14008 — so, yes, it has been a popular way to exercise presidential power since 1789.

Still, by the end of January, Biden had signed “more than double the amount any president in modern U.S. [history] had signed in their own first months,” Dr. Adam Warber, a Clemson political science professor, told People. “Although the number is large…it is not a huge surprise because Democrats want to reverse a good portion of the policy actions that were undertaken by the Trump administration.” Dr. Warber also cites that an impetus behind Biden’s executive orders likely relates to the “high polarization in Washington politics,” an aftereffect of the Trump era that the country will likely be feeling for quite some time. It is a balancing act, however: President Biden has spoken countless times about unity, about working for all Americans, but an executive order is often viewed as divisive, whether that’s a fair judgement or not.

As of early February, President Biden’s executive actions have touched on a wide range of topics, from immigration, transgender rights and racial justice to climate change and COVID-19 relief-related directives. Notably, President Biden has used presidential powers to preserve Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) and rejoin the Paris climate agreement. Additionally, he has issued executive orders to repeal the Trump administration’s bigoted travel ban on countries with majority Muslim populations; revoke the permit for the Keystone XL pipeline; and take more measures to fill supply shortfalls and combat COVID-19 with the Defense Production Act. On the other hand, President Biden has made it clear in the past that he feels using an executive order to cancel student loan debt in totality to be a “potential abuse of his executive powers.” Whether you agree with the directives or not, it’s clear that executive orders are often a clear, concise and expedient way to create change.

Let’s Begin…

Create and share a new lesson based on this one.

About TED-Ed Animations

TED-Ed Animations feature the words and ideas of educators brought to life by professional animators. Are you an educator or animator interested in creating a TED-Ed Animation? Nominate yourself here »

Meet The Creators

The US Constitution states that the president of the United States has two major powers at his/her disposal – the power to veto bills from Congress and the power to issue Executive orders. The reason the founding fathers did not want to give the president too much authority is because they feared he or she would behave like a king or a dictator. Therefore, they established a system of checks and balances between the executive, legislative, and judicial branches.

If you research Executive Orders issued by modern day presidents, for example beginning with President Roosevelt, you will see that presidents have steadily used executive orders to expand their power by establishing agencies. By studying past executive orders, you will also see moments in time when presidents excluded various groups of people from American freedoms. Explore the various executive orders issued by United States presidents beginning with FDR. Are there any executive orders that stand out to you? Do you notice any patterns among the presidents?

Executive orders are extremely important for presidents trying to pass certain policies in an emergency or when they cannot work with Congress. What do you think presidents should do to get Congress to assist them in their agenda? What should be a president’s most important goal be if she or he is issuing an executive order?

Over the past few decades, political participation in US has been on a steady decline. Individuals who are of voting age and eligible to vote (that is, they are citizens who have not been convicted of felonies in particular states) have not even bothered to register to vote. Why do you think so many Americans who can vote for the president choose not to do so? What can local, state level, and national leaders do to convince people to register to vote and then actually turn out to vote on election day?

Since most states require that individuals must register to vote several days or weeks before an election, are the costs of preparing to vote too great? Are voters asked to do too much in the voting process? When the election day arrives, polls are only open for about a maximum of twelve hours. If the US extended voting over several days, do you think political participation would increase or are voters not interested for other reasons?

Imagine you were one of the founding fathers. What would you change about the US powers given to the president? How would you ensure that one person would not abuse his/her power in generations to come?

National Constitution Center

Smart conversation from the National Constitution Center

Executive Orders 101: What are they and how do Presidents use them?

January 23, 2017 by NCC Staff

One of the first “orders” of business for President Donald Trump was signing an executive order to weaken Obamacare, while Republicans figure out how to replace it. So what powers do executive orders have?

In President Trump’s case, his executive order on Obamacare allows federal agencies to “take all actions consistent with law to minimize the unwarranted economic and regulatory burdens of the [Affordable Care] act, and prepare to afford the states more flexibility and control to create a more free and open health care market.”

The constitutional basis for the executive order is the President’s broad power to issue executive directives. According to the Congressional Research Service, there is no direct “definition of executive orders, presidential memoranda, and proclamations in the U.S. Constitution, there is, likewise, no specific provision authorizing their issuance.”

But Article II of the U.S. Constitution vests executive powers in the President, makes him the commander in chief, and requires that the President “shall take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed.” Laws can also give additional powers to the President.

While an executive order can have the same effect as a federal law under certain circumstances, Congress can pass a new law to override an executive order, subject to a presidential veto.

Every President since George Washington has used the executive order power in various ways. Washington’s first orders were for executive departments to prepare reports for his inspection, and a proclamation about the Thanksgiving holiday. After Washington, other Presidents made significant decisions via executive orders and presidential proclamations.

President Abraham Lincoln suspended the writ of habeas corpus during the Civil War using executive orders in 1861. Lincoln cited his powers under the Constitution’s Suspension Clause, which states, “the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus shall not be suspended, unless when in cases of rebellion and invasion the public safety may require it.”

Supreme Court Chief Justice Roger Taney, in his role as a federal circuit judge, ruled that Lincoln’s executive order was unconstitutional in a decision called Ex Parte Merryman. Lincoln and the Union army ignored Taney, and Congress didn’t contest Lincoln’s habeas corpus decisions.

Two other executive orders comprised Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation. Lincoln was fearful that the Emancipation Proclamation would be overturned by Congress or the courts after the war’s end, since he justified the proclamation under his wartime powers. The ratification of the 13 th Amendment ended that potential controversy.

President Franklin Roosevelt established internment camps during World War II using Executive Order 9066. Roosevelt also used an executive order to create the Works Progress Administration.

And President Harry Truman mandated equal treatment of all members of the armed forces through executive orders. However, Truman also saw one of his key executive orders invalidated by the Supreme Court in 1952, in a watershed moment for the Court that saw it define presidential powers in relation to Congress.

The Court ruled in Youngstown Sheet and Tube Co. v. Sawyer that an executive order putting steel mills during the Korean War under federal control during a strike was invalid. “The President’s power to see that the laws are faithfully executed refutes the idea that he is to be a lawmaker,” Justice Hugo Black said in his majority opinion.

It was Justice Robert Jackson’s concurring opinion that stated a three-part test of presidential powers that has since been used in arguments involving the executive’s overreach of powers.

Jackson said the President’s powers were at their height when he had the direct or implied authorization from Congress to act; at their middle ground – the Zone of Twilight, as he put it, when it was unsure which branch could act; and at their “lowest ebb” when a President acted against the expressed wishes of Congress.

The use of executive orders also played a key role in the Civil Rights movement. In 1957, President Dwight Eisenhower used an executive order to put the Arkansas National Guard under federal control and to enforce desegregation in Little Rock. Affirmative action and equal employment opportunity actions were also taken by Presidents Kennedy and Johnson using executive orders.

President Roosevelt issued the most executive orders, according to records at the National Archives. He issued 3,728 orders between 1933 and 1945, as the country dealt with the Great Depression and World War II.

President Truman issued a robust 896 executive orders over almost eight years in office. President Barack Obama issued 277 orders during his presidency. His predecessor, President George W. Bush, issued 291 orders over eight years, while President Bill Clinton had 364 executive orders during his two terms in office.

The most-active President in the post-World War II era, in terms of executive orders, was Jimmy Carter, who averaged 80 orders per year during his four-year term.

A Constitutional Conversation at Crystal Bridges

Celebrating the opening of a new exhibition at Crystal Bridges with a discussion exploring the importance of the Constitution and free speech to democracy

Источники информации:

- http://www.history.com/topics/us-government/executive-order

- http://www.reference.com/history/presidential-executive-order-work-4906e5bbacf13031

- http://ed.ted.com/lessons/how-do-executive-orders-work-christina-greer

- http://constitutioncenter.org/blog/executive-orders-101-what-are-they-and-how-do-presidents-use-them/