How is made cheese

How is made cheese

The History of Cheese

The Spruce Eats / Julie Bang

The production of cheese predates recorded history and was most likely discovered by accident during the transport of fresh milk in the organs of ruminants such as sheep, goats, cows, and buffalo. In the millennia before refrigeration, cheese became a way to preserve milk. Although it is unknown where cheese production was first discovered, evidence of early cheesemaking is prevalent in the Middle East, Europe, and Central Asia.

Early Cheeses

It is thought that cheese was first discovered around 8000 BC around the time when sheep were first domesticated. Rennet, the enzyme used to make cheese, is naturally present in the stomachs of ruminants. The leak-proof stomachs and other bladder-like organs of animals were often put to use to store and transport milk and other liquids. Without refrigeration, warm summer heat in combination with residual rennet in the stomach lining would have naturally curdled the milk to produce the earliest forms of cheese.

These milk curds were strained, and salt was added for extra preservation, giving birth to what we now know as «cheese.» Even with the addition of salt, warm climates meant that most cheeses were eaten fresh and made daily. Early Roman texts describe how ancient Romans enjoyed cheese often. They enjoyed a wide variety of cheeses, and cheese making was already considered an art form. They provided hard cheese for the Roman legions.

The word cheese comes from the Latin word caseus, the root of which is traced back to the proto-Indo-European root kwat, meaning to ferment or become sour.

European Cheeses

As cheesemaking spread to the cooler climates of Northern Europe, less salt was needed for preservation, which led to creamier, milder varieties of cheese. These cooler climates also saw the invention of aged, ripened, and blue cheeses. Many of the cheeses that we are familiar with today (cheddar, gouda, parmesan, camembert) were first produced in Europe during the Middle-Ages.

Modern Cheeses

Mass production of cheese didn’t occur until 1815 in Switzerland when the first cheese factory was built. Soon after, scientists discovered how to mass-produce rennet and industrial cheese production spread like wildfire.

Pasteurization made soft cheeses safer, reducing the risk of spreading tuberculosis, salmonellosis, listeriosis, and brucellosis. Outbreaks still occur from raw milk cheeses, and pregnant women are warned not to eat soft-ripened cheeses and blue-veined cheeses.

With the American industrial food, a revolution came in the invention of processed cheese. Processed cheese combines natural cheese with milk, emulsifiers, stabilizers, flavoring, and coloring. This inexpensive cheese product melts easily and consistently and has become an American favorite. Production of processed cheese products skyrocketed during the World War II era. Since this time, Americans have consistently consumed more processed cheese than natural cheeses.

New Directions with Cheese

Handmade artisan cheese is making a comeback in a major way. Classic cheesemaking methods are being adopted by small farmers and creameries across the United States. Specialty cheese shops, which were once dominated by imported artisan cheese, are now filling up with locally made and handcrafted cheeses.

Cheese

Background

The first cheeses were «fresh,» that is, not fermented. They consisted solely of salted white curds drained of whey, similar to today’s cottage cheese. The next step was to develop ways of accelerating the natural separation process. This was achieved by adding rennet to the milk. Rennet is an enzyme from the stomachs of young ruminants—a ruminant is an animal that chews its food very thoroughly and possesses a complex digestive system with three or four stomach chambers; in the United States, cows are the best known creatures of this kind. Rennet remains the most popular way of «starting» cheese, though other starting agents such as lactic acid and various plant extracts are also used.

By A.D. 100 cheese makers in various countries knew how to press, ripen, and cure fresh cheeses, thereby creating a product that could be stored for long periods. Each country or region developed different types of cheese that reflected local ingredients and conditions. The number of cheeses thus developed is staggering. France, famous for the quality and variety of its cheeses, is home to about 400 commercially available cheeses.

The next significant step to affect the manufacture of cheese occurred in the 1860s, when Louis Pasteur introduced the process that bears his name. Pasteurization entails heating milk to partially sterilize it without altering its basic chemical structure. Because the process destroys dangerous micro-organisms, pasteurized milk is considered more healthful, and most cheese is made from pasteurized milk today.

The first and simplest way of extending the length cheese would keep without spoiling was simply ageing it. Aged cheese was popular from the start because it kept well for domestic use. In the 1300s, the Dutch began to seal cheese intended for export in hard rinds to maintain its freshness, and, in the early 1800s, the Swiss became the first to process cheese. Frustrated by the speed with which their cheese went bad in the days before refrigeration, they developed a method of grinding old cheese, adding filler ingredients, and heating the mixture to produce a sterile, uniform, long-lasting product. Another advantage of processing cheese was that it permitted the makers to recycle edible, second-grade cheeses in a palatable form.

Prior to the twentieth century, most people considered cheese a specialty food, produced in individual households and eaten rarely. However, with the advent of mass production, both the supply of and the demand for cheese have increased. In 1955, 13 percent of milk was made into cheese. By 1984, this percentage had grown to 31 percent, and it continues to increase. Interestingly, though processed cheese is now widely available, it represents only one-third of the cheese being made today. Despite the fact that most cheeses are produced in large factories, a majority are still made using natural methods. In fact, small, «farmhouse» cheese making has made a comeback in recent years. Many Americans now own their own small cheese-making businesses, and their products have become quite popular, particularly among connoisseurs.

Raw Materials

Cheese is made from milk, and that milk comes from animals as diverse as cows, sheep, goats, horses, camels, water buffalo, and reindeer. Most cheese makers expedite the curdling process with rennet, lactic acid, or plant extracts, such as the vegetable rennet produced from wild artichokes, fig leaves, safflower, or melon.

In addition to milk and curdling agents, cheeses may contain various ingredients added to enhance flavor and color. The great cheeses of the world may acquire their flavor from the specific bacterial molds with which they have been inoculated, an example being the famous Penicillium roqueforti used to make France’s Roquefort and England’s Stilton. Cheeses may also be salted or dyed, usually with annatto, an orange coloring made from the pulp of a tropical tree, or carrot juice. They may be washed in brine or covered with ashes. Cheese makers who wish to avoid rennet may encourage the bacterial growth necessary to curdling by a number of odd methods. Some cheeses possess this bacteria because they are made from unpasteurized milk. Other cheeses, however, are reportedly made from milk in which dung or old leather have been dunked; still others acquire their bacteria from being buried in mud.

The unusual texture and flavor of processed cheese are obtained by combining several types of natural cheese and adding salt, milk-fat, cream, whey, water, vegetable oil, and other fillers. Processed cheese will also have preservatives, emulsifiers, gums, gelatin, thickeners, and sweeteners as ingredients. Most processed cheese and some natural cheeses are flavored with such ingredients as paprika, pepper, chives, onions, cumin, car-away seeds, jalapeño peppers, hazelnuts, raisins, mushrooms, sage, and bacon. Cheese can also be smoked to preserve it and give it a distinctive flavor.

The Manufacturing

Process

Although cheese making is a linear process, it involves many factors. Numerous varieties of cheese exist because ending the simple preparation process at different points can produce different cheeses, as can varying additives or procedures. Cheese making has long been considered a delicate process. Attempts to duplicate the success of an old cheese factory have been known to fail because conditions at a new factory do not favor the growth of the proper bacteria.

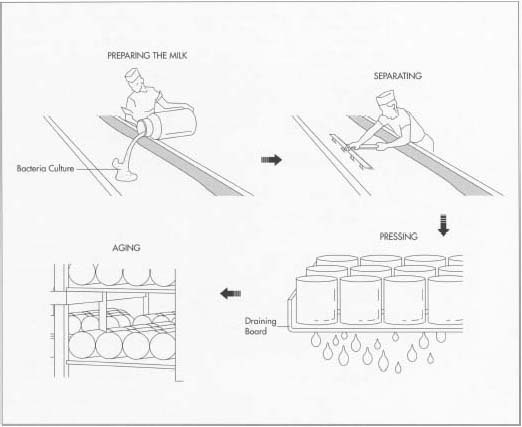

Preparing the milk

Separating the curds from the whey

Pressing the curds

Ageing the cheese

Wrapping natural cheese

Making and wrapping processed

cheese

Quality Control

Cheese making has never been an easily regulated, scientific process. Quality cheese has always been the sign of an experienced, perhaps even lucky cheese maker insistent upon producing flavorful cheese. Subscribing to analytical tests of cheese characteristics may yield a good cheese, but cheese making has traditionally been a chancy endeavor. Developing a single set of standards for cheese is difficult because each variety of cheese has its own range of characteristics. A cheese that strays from this range will be bad-tasting and inferior. For example, good soft blue cheese will have high moisture and a high pH; cheddar will have neither.

One controversy in the cheese field centers on whether it is necessary to pasteurize the milk that goes into cheese. Pasteurization was promoted because of the persistence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, a pathogen or disease-causing bacteria that occurs in milk products. The United States allows cheeses that will be aged for over sixty days to be made from unpasteurized milk; however, it requires that many cheeses be made from pasteurized milk. Despite these regulations, it is possible to eat cheeses made from unpasteurized milk to no ill effect. In fact, cheese connoisseurs insist that pasteurizing destroys the natural bacteria necessary for quality cheese manufacture. They claim that modern cheese factories are so clean and sanitary that pasteurization is unnecessary. So far, the result of this controversy has merely been that connoisseurs avoid pasteurized milk cheeses.

Regulations exist so that the consumer can purchase authentic cheeses with ease. France, the preeminent maker of a variety of natural cheeses, began granting certain regions monopolies on the manufacture of certain cheeses. For example, a cheese labeled «Roquefort» is guaranteed to have been ripened in the Combalou caves, and such a guarantee has existed since 1411. Because cheese is made for human consumption, great care is taken to insure that the raw materials are of the highest quality, and cheese intended for export must meet particularly stringent quality control standards.

Because they possess such disparate characteristics, different types of cheese are required to meet different compositional standards. Based on its moisture and fat content, a cheese is labeled soft, semi-soft, hard, or very hard. Having been assigned a category, it must then fall within the range of characteristics considered acceptable for cheeses in that category. For example, cheddar, a hard cheese, can contain no more than 39 percent water and no less than 50 percent fat. In addition to meeting compositional standards, cheese must also meet standards for flavor, aroma, body, texture, color, appearance, and finish. To test a batch of cheese, inspectors core a representative wheel vertically in several places, catching the center, the sides, and in between. The inspector then examines the cheese to detect any inconsistencies in texture, rubs it to determine body (or consistency), smells it, and tastes it. Cheese is usually assigned points for each of these characteristics, with flavor and texture weighing more than color and appearance.

Processed cheese is also subject to legal restrictions and standards. Processed American cheese must contain at least 90 percent real cheese. Products labeled «cheese food» must be 51 percent cheese, and most are 65 percent. Products labeled «cheese spread» must also be 51 percent cheese, the difference being that such foods have more water and gums to make them spreadable. «Cheese product» usually refers to a diet cheese that has more water and less cheese than American cheese, cheese food, or cheese spread, but the specific amount of cheese is not regulated. Similarly, «imitation cheese» is not required to contain a minimum amount of cheese, and cheese is usually not its main ingredient. In general, quality processed cheese should resemble cheese and possess some cheesy flavor, preferably with a «bite» such as sharp cheddar cheese has. The cheese should be smooth and evenly colored; it should also avoid rubberiness and melt in the mouth.

Where To Learn More

Books

Brown, Bob. The Complete Book of Cheese. Gramercy Publishing, 1955.

Carr, Sandy. The Simon and Schuster Pocket Guide to Cheese. Simon and Schuster, 1981.

Kosikowski, Frank. Cheese and Fermented Milk Foods. Cornell University, 1966.

Mills, Sonya. The World Guide to Cheese. Gallery Books, 1988.

Timperley, Carol and Cecilia Norman. A Gourmet’s Guide to Cheese. HP Books, 1989.

Periodicals

«American Cheese and ‘Cheeses’,» Consumer Reports. November, 1990, pp. 728-732.

Birmingham, David. «Gruyere’s Cheese-makers,» History Today. February, 1991, pp. 21-26.

Raichlen, Steven. «Farmhouse Cheeses,» Yankee. February, 1991, pp. 84-92.

How is Cheese Made?

From cow to curd, there are many steps along the way to make the cheeses we all know and love.

What is cheese made of? It all starts with collecting milk from dairy farms. Once it’s brought to the cheese plant, the cheesemakers check the milk and take samples to make sure it passes quality and purity tests.

Once it passes, the milk goes through a filter and is then standardized – that is, they may add in more fat, cream or protein. This is important because cheesemakers need to start with the same base milk in order to make a consistent cheese. After the milk is standardized, it’s pasteurized. Pasteurization is necessary because raw milk can harbor dangerous bacteria, and pasteurization kills those bacteria.

Rennet causes the milk to gel similar to yogurt, before the curds (the solids) separate from the whey (the liquid). The amount of rennet and time needed for it to separate into curds can vary from cheese to cheese.

Once it starts to gel, the cheesemakers cut it, which allows the whey to come out. Drier cheeses are often cut more to form smaller curds, so more of the moisture comes out, while curds cut less are larger and are moister. Once the curds are cut, they’re stirred and heated to release even more whey. At this point, the curd is separated from the whey, and it’s time to start making the cheese look more like cheese! Depending on the type of cheese, this can happen one of two ways:

While the cheese is pressed, more whey comes out, so it eventually becomes the shape and consistency of cheeses we know.

Once the cheese is shaped, it may be aged for a while before its ready to eat.

Want to see it in action? We sent a team to Fiscalini Farms in Modesto, California, to learn more about how they make their award-winning cheeses.

According to dairy farmer Brian Fiscalini, world-class cheese comes from stellar milk. From there, the cheese travels to the cheese plant and the magic begins. To learn more about the cheese making process, watch this video:

How Cheese is Made

The process of making cheese is often described as part art, and part science – and for good reason. There are hundreds of distinct cheese varieties produced around the world today, and all are made with varying recipes, techniques, and trade secrets. Just think of how soft, creamy Brie differs from firm, salty Parmesan. Or how lacy Baby Swiss is so much more delicate than sharp, aged Cheddar.

Despite all their delicious deviations, all varieties of natural cheese go from dairy farm to our ham sandwiches and hors d’oeuvre platters by undergoing the same essential process. To see this process at work most simply, we needn’t do more than look back to cheese’s origins.

Though no one knows for sure when cheese was first made, many believe a nomadic Arab created it by accident while carrying a saddlebag full of milk on his horse. The hot sun and galloping movement caused the milk to ferment, turning it into simple curds and whey.

Of course the process of making cheese has become much more sophisticated over these many thousands of years. But once the milk has been prepared, all cheeses are crafted using some variance of the same four-step process:

The Milk

Liquid milk is the main raw material cheese makers work with, and it can come from any variety of mammal sources, including cows, sheep, goats, water buffalo, and even camels and reindeer. The breeds, feed, milking cycles and transportation methods dairy farmers choose to use can all affect the flavour of the milk, and ultimately, the cheese made from it.

While many modern dairies now pasteurise milk sold to large cheese factories, there is some disagreement in the field as to whether this is necessary. In fact, most cheese connoisseurs will tell you the best cheeses are the old-fashioned kinds made from milk in its raw, natural, unpasteurised state.

Step 1: Curdling

After the milk is prepared, it is curdled to separate the solid components (curds) from the liquid components (whey). To do this, cheese makers usually add a lactic starter, rennet, or both, depending on the type of cheese being made.

A lactic starter is used when making soft “fresh” cheeses like cottage cheese and ricotta. This special strain of lactic acid bacteria causes milk to separate into small grains of curd.

Rennet is employed when making firm or semi-firm cheeses such as Raclette and Tomme. This enzyme, which traditionally comes from the lining of a calf’s stomach, causes the milk to separate into larger grains of curd. Today, many cheeses are made with synthetic or “vegetarian” rennet produced from fig leaves, artichokes or melons.

When lactic starter and rennet are used together, they produce cheeses that display a combination of both soft and firm characteristics. The best examples of these are semi-soft or semi-crumbly cheeses like Camembert, Munster and many of the blue-veined varieties.

Step 2: Draining

Draining involves further removing the whey to obtain the desired moisture content for the cheese being made. As the curd is allowed to rest or “set up,” the acidity levels rise, the bacteria multiply and the unique flavour of the cheese begins to develop.

It is at this point that cheese making recipes begin to greatly diverge in technique. In a technique called “stretching,” for example, the curd is stretched and kneaded in hot water to make stringy, pulled cheeses like Mozzarella and Provolone.

Step 3: Pressing

Most cheeses attain their final shape and size when the curds are pressed into forms or moulds. These moulds are designed to expel moisture, so cheeses subjected to more pressure turn out drier and firmer. Finely textured Cheddar, for example, might be pressed for up to three days, while a more crumbly Cheshire might be pressed for only 24 hours.

During this stage, it is also common for cheeses to be further treated with various ingredients such as salt, herbs, or food colourings. They may also be smoked, covered in brine baths or ashes, or inoculated with bacterial moulds. The most famous of these is Penicillium roqueforti used to make bold blue cheeses like Roquefort and Stilton.

Step 4: Ripening

Once a cheese has been curdled, drained, and pressed, the process of ripening, or maturation can begin. During this process, expert cheese agers (affineurs) closely monitor moisture, temperature and oxygen, all of which influence microbes in the cheese to slowly create its unique and specific texture, flavour and aroma.

For soft, fresh cheeses, the ripening process may last only a few hours or days, but for long-aged cheeses it may go on for several months or more. The undeniably intense Parmigiano Reggiano from Italy is aged two full years before it is sold.

How Is Cheese Made?

Article Overview: This helpful article details how cheese is made in today’s agricultural practices, as well as a step-by-step guide for how to make cheese.

If you read our ultimate cheese guide, your mouth was probably watering by the end of it. After all, who doesn’t love cheese? We shred it on top of pasta or potatoes, add a slice to our favorite sandwich or enjoy it as a fabulous snack or appetizer with a glass of wine. We can all agree cheese is delicious, but even self-declared cheese lovers may not know much about the cheese-making process.

At S. Clyde Weaver, we know this process inside and out, so we’re here to demystify the magic of the art of cheese making. We’ll look at the ingredients that go into cheese making and break down the process, step by step. The next time you enjoy your favorite cheese, you may have a greater appreciation for the labor and care that goes into creating this delicious product.

Shop Our Cheeses

What Is Cheese Made Of?

There are countless types of cheese, all of which have their own distinct textures and flavors, but all these cheeses start out with the same star ingredient: milk. While all cheeses have milk in common, the type of milk can differ from cheese to cheese. Some common types of milk used in cheese making include:

Even more obscure types of milk can be used to make regional specialty cheeses. For example, camel’s milk is the basis for the South African caracane cheese. Other cheeses can be made from horse’s or even yak’s milk.

Milk doesn’t turn into delicious cheese on its own. Another important ingredient in cheese is a coagulant, which helps the milk turn into curds. The coagulant may be a type of acid or, more commonly, rennet. Rennet is an enzyme complex that is genetically engineered through microbial bioprocessing. Traditional rennet cheeses are actually made with rennin, the enzyme rennet is meant to replicate. Rennin, also known as chymosin, is an enzyme that is naturally produced in the stomachs of calves and other mammals to help them digest milk.

Milk and coagulant are the main components of cheese, but cheese can also include sources of flavoring, such as salt, brine, herbs, spices and even wine. Some cheeses may be made with identical ingredients, but the end product will differ based on different aging processes.

How Is Cheese Made?

So, how does milk turn into cheese? It’s a natural process that requires some help from artisans, known as fromagers or, simply, cheesemakers. Another term you may hear is a cheesemonger, but this technically refers to someone who sells cheese.

With so many different varieties of cheese, of course, there are differences in the cheese-making process, depending on what cheese is being made. However, all cheese making follows the same general process, especially when it comes to the earlier steps. The cheese-making process comes down to 10 essential steps. We’ll explain them more in the next section, but first, let’s do a quick overview of the process:

The Cheese-Making Process

Now, let’s take a closer look at the magic of cheese making, starting with simple milk all the way to the finished product.

Step 1: Preparing the Milk

Since milk is the star of the show, to make cheese just right, you need your milk to be just right. “Just right” will differ from cheese to cheese, so many cheesemakers start by processing their milk however they need to in order to standardize it. This may involve manipulating the protein-to-fat ratio.

It also often involves pasteurization or a more mild heat treatment. Heating the milk kills organisms that could cause the cheese to spoil and can also prime the milk for the starter cultures to grow more effectively. Once the milk has been heat treated or pasteurized, it is cooled to 90°F so it is ready for the starter cultures. If a cheese calls for raw milk, it will need to be heated to 90°F before adding the starter cultures.

Step 2: Acidifying the Milk

The next step in the cheese-making process is adding starter cultures to acidify the milk. If you’ve ever tasted sour milk, then you know that left long enough, milk will acidify on its own. However, there is any number of bacteria that can grow and sour milk. Instead of letting milk sour on its own, the modern cheese-making process typically standardizes this step.

Cheesemakers add starter and non-starter cultures to the milk that acidify it. The milk should already be 90°F at this point, and it must stay at this temperature for approximately 30 minutes while the milk ripens. During this ripening process, the milk’s pH level drops, and the flavor of the cheese begins to develop.

Step 3: Curdling the Milk

The milk is still liquid milk at this point, so cheesemakers need to start manipulating the texture. The process of curdling the milk can also happen naturally. In fact, some nursing animals, such as calves, piglets or kittens, produce the rennin enzyme in their stomachs to help them digest their mother’s milk. Cheesemakers cause the same process to take place in a controlled way.

In the past, natural rennin was typically the enzyme of choice for curdling the milk, but cheesemakers today usually use rennet, the lab-created equivalent. Rennet inactivates the protein kappa casein, turning it into para-kappa-casein. The important thing to understand is simply that this reaction allows the milk to form coagulated lumps, known as curds. As the solid curd forms, a liquid byproduct remains, known as whey.

Step 4: Cutting the Curd

The curds and whey mixture is allowed to separate and ferment until the pH reaches 6.4. At this point, the curd should form a large coagulated mass in the cheese-making vat. Then, cheesemakers use long curd knives that can reach the bottom of the vat to cut through the curds. Cutting the curd creates more surface area on the curd, which allows the curds and why to separate even more.

Cheesemakers usually make crisscrossing cuts vertically, horizontally and diagonally to break up the curd. The size of the curds after cutting can influence the cheese’s level of moisture. Larger chunks of curd retain more moisture, leading to a moisture cheese, and smaller pieces of curd can lead to a drier cheese.

Step 5: Processing the Curd

After being cut, the curd continues to be processed. This might involve cooking the curds, stirring the curds or both. All of this processing is still aimed at the same goal of separating the curds and whey. In other words, the curds continue to acidify and release moisture as they are processed. The more the curds are cooked and stirred, the drier the cheese will be.

Another way curd can be processed at this stage is through washing. Washing the curd means replacing whey with water. This affects the flavor and texture of the cheese. Washed curd cheeses tend to be more elastic and have a nice, mild flavor. Some examples of washed curd cheeses are gouda, havarti and Swedish fontina.

Step 6: Draining the Whey

At this point, the curds and whey should be sufficiently separated, so it’s time to remove the whey completely. This means draining the whey from the vat, leaving only the solid chunks of curd. These chunks could be big or small, depending on how finely the curd has been cut. With all the whey drained, the curd should now look like a big mat.

There are different means of draining whey. In some cases, cheesemakers allow it to drain off naturally. However, especially when it comes to harder cheeses that require a lower moisture content, cheesemakers are likely to get help from a mold or press. Putting pressure on the curd compacts and forces more whey out.

Step 7: Cheddaring the Cheese

With the whey drained, the curd should form a large slab. For some cheeses, another step remains to remove even more moisture from the curd. This step is known as cheddaring. After cutting the mat of curd into sections, the cheesemaker will stack the individual slabs of curd. Stacking the slabs puts pressure on them, forcing out more moisture.

Periodically, the cheesemaker will repeat the process, cutting up the slabs of curd again and restacking them. The longer this process goes on, the more whey is removed from the curd, resulting in a denser, more crumbly finished cheese texture. Fermentation also continues during the cheddaring process. Eventually, the curd should reach a pH of 5.1 to 5.5. When it’s ready, the cheesemaker will mill the curd slabs, producing smaller pieces.

Step 8: Salting the Cheese

The curd is now beginning to look more like cheese in its final form. To add flavor, cheese makers can salt or brine the cheese at this point. This can either involve sprinkling on dry salt or submerging the cheese into brine. An example of a cheese that gets soaked in brine is mozzarella. Drier cheeses will be dry salted.

Some cheeses have flavor added in other forms as well. Some examples of spices that find their way into some types of cheese are horseradish, garlic, paprika, habanero and cloves. Cheese can also contain herbs, such as dill, basil, chives or rosemary. The options for flavoring cheeses are endless. For many cheeses, though, the focus is simply on developing the natural flavors of the cheese and adding salt to intensify those flavors.

Step 9: Shaping the Cheese

There are no more ingredients to add to the cheese at this point, so it’s ready to be shaped. This is where the final product really begins to reveal itself. Even with so much moisture removed from the curd, it is still malleable and soft. Therefore, cheesemakers are able to press the curd into molds to create standardized shapes.

Molds can take the form of baskets or hoops. Baskets are molds that are only open on one end, and hoops are bottomless molds, meaning they only wrap around the sides of the curd. In either case, the milled curd mixture is pressed into the mold and left there for a certain amount of time to solidify into the right shape. These molds are usually round or rectangular.

Step 10: Aging the Cheese

For some cheeses, the process is already finished, but for many cheeses, what’s known as aging remains. Aging should occur in a controlled, cool environment. As the cheese ages, molecular changes take place that cause the cheese to harden and the flavor to intensify. The aging process can take anywhere from a few days to many years. In some cases, mold develops, which adds unique color and flavor to the cheese.

Once the cheese has finished aging, it is finally ready to be enjoyed by consumers. Cheeses can be sold in whole weels or blocks or by the wedge. When you know how much time, effort and care went into making your favorite cheese, it’s likely to taste even more delicious.

How Is Fresh Cheese Made?

Now that we’ve looked at the general production of cheese, you may be wondering about the particulars of how certain types of cheeses are made. For instance, what about fresh cheese? Fresh cheeses tend to be smooth, creamy and mild in flavor. There is one main difference that separates fresh cheese like feta, ricotta or fresh mozzarella, from other cheeses — they are not aged.

Fresh cheeses must still go through the bulk of the steps we outlined above to varying degrees. If all you did was drain some of the whey off after initially forming curds and whey, you would have cottage cheese. For other fresh cheeses, you must continue to strain the curds to remove more moisture and pack the cheese into a shape. Making fresh cheese is a simpler process, so some home cooks attempt this type of cheese making in their own kitchens.

How Is Cheese Aged?

Aging cheese doesn’t just mean leaving it lying around for a while. It is a carefully controlled and timed process, and even subtle changes can affect the texture and taste of the finished cheese. In general, cheeses are aged in cool environments with relatively high humidity levels. Another term for aging when it comes to cheese is ripening. There are two basic types of ripening that can take place:

Beyond these basic distinctions, it’s helpful to understand the process that goes into aging specific categories of aged cheese, including red mold (also known as washed rind) cheese, white mold (or bloomy rind) cheese and blue cheese. Let’s take a look.

1. Red Mold Cheese

As the name suggests, red mold cheeses are covered in a reddish rind. Some popular types of red mold cheeses include French Morbier, Reblochon and Taleggio. Red mold cheeses are also often called washed rind cheeses, which hints at how they are aged. These cheeses are stored in a very humid environment and are washed frequently in some type of liquid, such as wine or a salty brine, for example. The thinner the cheese, the more the liquid will permeate and soften the cheese.

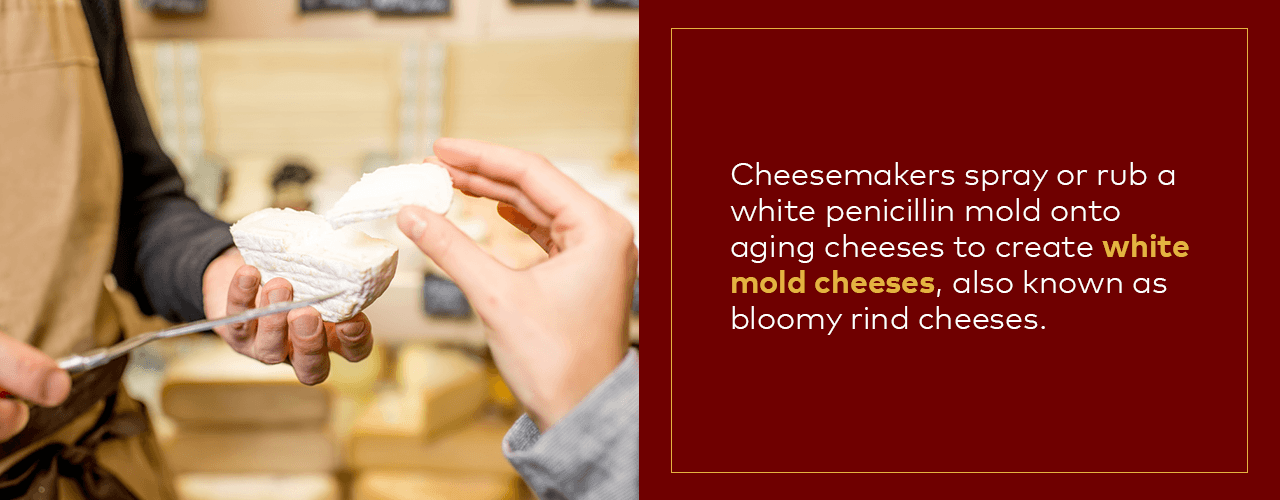

2. White Mold Cheese

Cheesemakers spray or rub a white penicillin mold onto aging cheeses to create white mold cheeses, also known as bloomy rind cheeses. When these cheeses are done aging, they are covered in a fuzzy white mold. This process results in a soft cheese that is creamy and pasty in texture. The most popular type of white mold cheese is brie, which is loved for its silky smoothness and mild flavor. Some other examples include French Normandy Camembert, Le Chevrot and St. Marcellin.

3. Blue Cheese

Some aged cheese doesn’t just have mold on the rind but throughout the inside of the cheese, as well. Blue cheeses, like the ever-popular French Roquefort, creamy gorgonzola or English blue stilton contain streaks of blue or green mold and have a characteristically sharp flavor. First, mold spores are added to the cheese at some point during the cheese-making process. Then, during the aging process, cheesemakers encourage the mold to grow and spread throughout the cheese by poking air tunnels into it.

Delicious Artisinal Cheeses From S. Clyde Weaver

At S. Clyde Weaver, we know our cheese. In fact, we have a century of experience creating delicious, artisan cheeses, meats and other delicacies to brighten Americans’ tables. When bland, over-processed cheese from the grocery store doesn’t cut it, you can find amazing cheeses, aged by experienced cheesemakers from S. Clyde Weaver. Some of our cheeses are aged for many years to produce the perfect texture and flavor. We even have creamy, delicious cheese spreads to try.

Whether you’re looking to assemble an amazing cheeseboard or you just want to try something new to add a punch of great flavor to your next meal, browse our selection of cheeses today.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/the-history-of-cheese-1328765_final-7d6dfb68029b4567b6abc2c7020d4080.gif)