How many plays has william shakespeare written

How many plays has william shakespeare written

Writing Plays

An English traveller of the time wrote,

“…there be more Playes in London than in all the partes of the worlde I have seene.”

A modern historian estimates that, between about 1560 and 1640, some 3000 new plays were written and performed in London.

Who wrote the plays?

William Shakespeare has become the most famous playwright of his time. He wrote or co-wrote almost 40 plays. But he was one of many writers producing plays in London at that time. The best known of the others are Christopher Marlowe and Ben Jonson. The grammar schools which boys like Shakespeare attended taught useful skills for playwrights. They memorised the history and myths of Ancient Greece and Rome; they wrote their own stories and recited these to classmates. Many playwrights also went to university. For example, Marlowe went to Cambridge. But some playwrights did not – like Shakespeare and Jonson for example. They probably learned the skills of writing plays whilst working as young actors.

What were the plays about?

Playwrights at this time were not too bothered about being original. They were content to re-work old stories or even use other people’s plots. Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew was a re-write of an earlier play and The Comedy of Errors was based on a plot from an ancient Roman writer named Plautus.

Part of the manuscript for the play ‘Sir Thomas More’. There are six different writers on this manuscript, the original playwrights and

others who have made edits and notes. It is believed some of these notes were written by Shakespeare. Apart from his signature, this is

the only surviving example of Shakespeare’s writing. © The British Library Board. (Harley 7368, f.9)

Did you know?

Like today, playwrights in Shakespeare’s time sometimes used blood and horror to entertain

the crowds.

In Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus, two characters, Chiron and Demetrius

• have their throats cut onstage;

• they are then cut up and baked in a meat pie;

• and then their mother is tricked into eating the pie!

Plays usually fell into three types

Histories were stories about England’s past. Marlowe wrote Edward II, while Shakespeare wrote plays about King John, Henry IV, Henry V, Henry VI, Richard III, and Henry VIII. His first play about Henry VI was so popular that he wrote a sequel and then a prequel.

Tragedies told unhappy tales which often ended in deaths, like Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet. John Webster had a big hit with The Duchess of Malfi and Shakespeare is famous for Othello and Hamlet. The tragedies often contained lots of blood and gore to entertain the crowds.

Comedies, on the other hand, could be relied upon for happy endings, often weddings. Shakespeare’s Two Gentlemen of Verona is especially happy; it ends with two weddings! Other comedies were more satirical. Ben Jonson wrote The Alchemist to make fun of London society.

Censorship

The Master of the Revels was an official of the royal court. His job was to grant licenses to theatres, theatre companies and plays. He would not license a play (give it permission to be performed) if it had political or religious views he didn’t like. Playwrights could not risk offending him. So they often set their plays in imaginary countries to make sure that nothing in the plot seemed critical of the royal court or the government.

What were the playwrights paid?

Playwrights were not usually wealthy. They got no royalties or repeat fees if their plays were performed many times. They just got a one-off fee for selling their play to an acting company. Often they had to share the money, because it was common to write as pairs or in groups. For example, Shakespeare co-wrote Henry VI Part 1 with someone else. We don’t know who. Philip Henslowe was a theatre owner who hired four writers called Chettle, Wilson, Dekker and Drayton. He usually paid them in instalments and they were sometimes writing several plays for him at the same time. But the fee for a play was worth having; in the 1590’s it was about £5. This may not sound much today, but it was about a year’s income to an average craftsman or shopkeeper at that time.

Shakespeare’s plays and poems of William Shakespeare

The early plays

Shakespeare arrived in London probably sometime in the late 1580s. He was in his mid-20s. It is not known how he got started in the theatre or for what acting companies he wrote his early plays, which are not easy to date. Indicating a time of apprenticeship, these plays show a more direct debt to London dramatists of the 1580s and to Classical examples than do his later works. He learned a great deal about writing plays by imitating the successes of the London theatre, as any young poet and budding dramatist might do.

Titus Andronicus

Titus Andronicus (c. 1589–92) is a case in point. As Shakespeare’s first full-length tragedy, it owes much of its theme, structure, and language to Thomas Kyd’s The Spanish Tragedy, which was a huge success in the late 1580s. Kyd had hit on the formula of adopting the dramaturgy of Seneca (the younger), the great Stoic philosopher and statesman, to the needs of a burgeoning new London theatre. The result was the revenge tragedy, an astonishingly successful genre that was to be refigured in Hamlet and many other revenge plays. Shakespeare also borrowed a leaf from his great contemporary Christopher Marlowe. The Vice-like protagonist of Marlowe’s The Jew of Malta, Barabas, may have inspired Shakespeare in his depiction of the villainous Aaron the Moor in Titus Andronicus, though other Vice figures were available to him as well.

The Senecan model offered Kyd, and then Shakespeare, a story of bloody revenge, occasioned originally by the murder or rape of a person whose near relatives (fathers, sons, brothers) are bound by sacred oath to revenge the atrocity. The avenger must proceed with caution, since his opponent is canny, secretive, and ruthless. The avenger becomes mad or feigns madness to cover his intent. He becomes more and more ruthless himself as he moves toward his goal of vengeance. At the same time he is hesitant, being deeply distressed by ethical considerations. An ethos of revenge is opposed to one of Christian forbearance. The avenger may see the spirit of the person whose wrongful death he must avenge. He employs the device of a play within the play in order to accomplish his aims. The play ends in a bloodbath and a vindication of the avenger. Evident in this model is the story of Titus Andronicus, whose sons are butchered and whose daughter is raped and mutilated, as well as the story of Hamlet and still others.

The early romantic comedies

Other than Titus Andronicus, Shakespeare did not experiment with formal tragedy in his early years. (Though his English history plays from this period portrayed tragic events, their theme was focused elsewhere.) The young playwright was drawn more quickly into comedy, and with more immediate success. For this his models include the dramatists Robert Greene and John Lyly, along with Thomas Nashe. The result is a genre recognizably and distinctively Shakespearean, even if he learned a lot from Greene and Lyly: the romantic comedy. As in the work of his models, Shakespeare’s early comedies revel in stories of amorous courtship in which a plucky and admirable young woman (played by a boy actor) is paired off against her male wooer. Julia, one of two young heroines in The Two Gentlemen of Verona (c. 1590–94), disguises herself as a man in order to follow her lover, Proteus, when he is sent from Verona to Milan. Proteus (appropriately named for the changeable Proteus of Greek myth), she discovers, is paying far too much attention to Sylvia, the beloved of Proteus’s best friend, Valentine. Love and friendship thus do battle for the divided loyalties of the erring male until the generosity of his friend and, most of all, the enduring chaste loyalty of the two women bring Proteus to his senses. The motif of the young woman disguised as a male was to prove invaluable to Shakespeare in subsequent romantic comedies, including The Merchant of Venice, As You Like It, and Twelfth Night. As is generally true of Shakespeare, he derived the essentials of his plot from a narrative source, in this case a long Spanish prose romance, the Diana of Jorge de Montemayor.

Shakespeare’s most classically inspired early comedy is The Comedy of Errors (c. 1589–94). Here he turned particularly to Plautus’s farcical play called the Menaechmi ( Twins). The story of one twin (Antipholus) looking for his lost brother, accompanied by a clever servant (Dromio) whose twin has also disappeared, results in a farce of mistaken identities that also thoughtfully explores issues of identity and self-knowing. The young women of the play, one the wife of Antipholus of Ephesus (Adriana) and the other her sister (Luciana), engage in meaningful dialogue on issues of wifely obedience and autonomy. Marriage resolves these difficulties at the end, as is routinely the case in Shakespearean romantic comedy, but not before the plot complications have tested the characters’ needs to know who they are and what men and women ought to expect from one another.

Shakespeare’s early romantic comedy most indebted to John Lyly is Love’s Labour’s Lost (c. 1588–97), a confection set in the never-never land of Navarre where the King and his companions are visited by the Princess of France and her ladies-in-waiting on a diplomatic mission that soon devolves into a game of courtship. As is often the case in Shakespearean romantic comedy, the young women are sure of who they are and whom they intend to marry; one cannot be certain that they ever really fall in love, since they begin by knowing what they want. The young men, conversely, fall all over themselves in their comically futile attempts to eschew romantic love in favour of more serious pursuits. They perjure themselves, are shamed and put down, and are finally forgiven their follies by the women. Shakespeare brilliantly portrays male discomfiture and female self-assurance as he explores the treacherous but desirable world of sexual attraction, while the verbal gymnastics of the play emphasize the wonder and the delicious foolishness of falling in love.

In The Taming of the Shrew (c. 1590–94), Shakespeare employs a device of multiple plotting that is to become a standard feature of his romantic comedies. In one plot, derived from Ludovico Ariosto’s I suppositi (Supposes, as it had been translated into English by George Gascoigne), a young woman (Bianca) carries on a risky courtship with a young man who appears to be a tutor, much to the dismay of her father, who hopes to marry her to a wealthy suitor of his own choosing. Eventually the mistaken identities are straightened out, establishing the presumed tutor as Lucentio, wealthy and suitable enough. Simultaneously, Bianca’s shrewish sister Kate denounces (and terrorizes) all men. Bianca’s suitors commission the self-assured Petruchio to pursue Kate so that Bianca, the younger sister, will be free to wed. The wife-taming plot is itself based on folktale and ballad tradition in which men assure their ascendancy in the marriage relationship by beating their wives into submission. Shakespeare transforms this raw, antifeminist material into a study of the struggle for dominance in the marriage relationship. And, whereas he does opt in this play for male triumph over the female, he gives to Kate a sense of humour that enables her to see how she is to play the game to her own advantage as well. She is, arguably, happy at the end with a relationship based on wit and companionship, whereas her sister Bianca turns out to be simply spoiled.

Shakespeare Authorship Debate

Introducing the Shakespeare Authorship Debate

Shakespeare Authorship

There are a number of theories surrounding the authorship of Shakespeare’s plays, but most are based on one of the following three ideas:

These theories have sprung up because the evidence surrounding Shakespeare’s life is insufficient – not necessarily contradictory. The following reasons are often cited as evidence that Shakespeare didn’t write Shakespeare (despite a distinct lack of evidence):

Someone Else Wrote the Plays Because

Exactly who wrote under the name of William Shakespeare and why they needed to use a pseudonym is unclear. Perhaps the plays were written to instill political propaganda? Or to hide the identity of some high-profile public figure?

The Main Culprits in the Authorship Debate Are

Christopher Marlowe

He was born in the same year as Shakespeare, but died around the same time that Shakespeare started to write his plays. Marlowe was England’s best playwright until Shakespeare came along – perhaps he didn’t die and continued writing under a different name? He was apparently stabbed in a tavern, but there is evidence that Marlowe was working as a government spy, so his death might have been choreographed.

Edward de Vere

Many of Shakespeare’s plots and characters parallel events in the life of Edward de Vere. Although this art-loving Earl of Oxford would have been educated enough to write the plays, their political content could have ruined his social standing – perhaps he needed to to write under a pseudonym?

Sir Francis Bacon

The theory that Bacon was the only man intelligent enough to write these plays has become known as Baconianism. Although it is unclear why he would have needed to write under a pseudonym, followers of this theory believe that he left behind cryptic ciphers in the texts to reveal his true identity.

William Shakespeare

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

Shakespeare married Anne Hathaway, eight years his senior, when he was 18. They had three children: Susanna and twins Judith and Hamnet. Hamnet died at the age of 11.

There is some dispute about how many plays Shakespeare wrote. The general consensus is 37.

Shakespeare wrote 154 sonnets. The most famous include Sonnet 18, with opening lines «Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?», and Sonnet 130, which begins «My mistress’ eyes are nothing like the sun.»

The cause of Shakespeare’s death is unknown. However, the vicar of the local church wrote in his journal some fifty years later that «Shakespeare, Drayton, and Ben Jonson had a merry meeting, and it seems drank too hard; for Shakespeare died of a fever there contracted.» The account cannot be verified but has led some scholars to speculate that Shakespeare may have died of typhus.

Shakespeare remains vital because his plays present people and situations that we recognize today. His characters have an emotional reality that transcends time, and his plays depict familiar experiences, ranging from family squabbles to falling in love to war. The fact that his plays are performed and adapted around the world underscores the universal appeal of his storytelling.

Read a brief summary of this topic

William Shakespeare, Shakespeare also spelled Shakspere, byname Bard of Avon or Swan of Avon, (baptized April 26, 1564, Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire, England—died April 23, 1616, Stratford-upon-Avon), English poet, dramatist, and actor often called the English national poet and considered by many to be the greatest dramatist of all time.

Shakespeare occupies a position unique in world literature. Other poets, such as Homer and Dante, and novelists, such as Leo Tolstoy and Charles Dickens, have transcended national barriers, but no writer’s living reputation can compare to that of Shakespeare, whose plays, written in the late 16th and early 17th centuries for a small repertory theatre, are now performed and read more often and in more countries than ever before. The prophecy of his great contemporary, the poet and dramatist Ben Jonson, that Shakespeare “was not of an age, but for all time,” has been fulfilled.

It may be audacious even to attempt a definition of his greatness, but it is not so difficult to describe the gifts that enabled him to create imaginative visions of pathos and mirth that, whether read or witnessed in the theatre, fill the mind and linger there. He is a writer of great intellectual rapidity, perceptiveness, and poetic power. Other writers have had these qualities, but with Shakespeare the keenness of mind was applied not to abstruse or remote subjects but to human beings and their complete range of emotions and conflicts. Other writers have applied their keenness of mind in this way, but Shakespeare is astonishingly clever with words and images, so that his mental energy, when applied to intelligible human situations, finds full and memorable expression, convincing and imaginatively stimulating. As if this were not enough, the art form into which his creative energies went was not remote and bookish but involved the vivid stage impersonation of human beings, commanding sympathy and inviting vicarious participation. Thus, Shakespeare’s merits can survive translation into other languages and into cultures remote from that of Elizabethan England.

Shakespeare the man

Although the amount of factual knowledge available about Shakespeare is surprisingly large for one of his station in life, many find it a little disappointing, for it is mostly gleaned from documents of an official character. Dates of baptisms, marriages, deaths, and burials; wills, conveyances, legal processes, and payments by the court—these are the dusty details. There are, however, many contemporary allusions to him as a writer, and these add a reasonable amount of flesh and blood to the biographical skeleton.

Early life in Stratford

The parish register of Holy Trinity Church in Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire, shows that he was baptized there on April 26, 1564; his birthday is traditionally celebrated on April 23. His father, John Shakespeare, was a burgess of the borough, who in 1565 was chosen an alderman and in 1568 bailiff (the position corresponding to mayor, before the grant of a further charter to Stratford in 1664). He was engaged in various kinds of trade and appears to have suffered some fluctuations in prosperity. His wife, Mary Arden, of Wilmcote, Warwickshire, came from an ancient family and was the heiress to some land. (Given the somewhat rigid social distinctions of the 16th century, this marriage must have been a step up the social scale for John Shakespeare.)

Stratford enjoyed a grammar school of good quality, and the education there was free, the schoolmaster’s salary being paid by the borough. No lists of the pupils who were at the school in the 16th century have survived, but it would be absurd to suppose the bailiff of the town did not send his son there. The boy’s education would consist mostly of Latin studies—learning to read, write, and speak the language fairly well and studying some of the Classical historians, moralists, and poets. Shakespeare did not go on to the university, and indeed it is unlikely that the scholarly round of logic, rhetoric, and other studies then followed there would have interested him.

Instead, at age 18 he married. Where and exactly when are not known, but the episcopal registry at Worcester preserves a bond dated November 28, 1582, and executed by two yeomen of Stratford, named Sandells and Richardson, as a security to the bishop for the issue of a license for the marriage of William Shakespeare and “ Anne Hathaway of Stratford,” upon the consent of her friends and upon once asking of the banns. (Anne died in 1623, seven years after Shakespeare. There is good evidence to associate her with a family of Hathaways who inhabited a beautiful farmhouse, now much visited, 2 miles [3.2 km] from Stratford.) The next date of interest is found in the records of the Stratford church, where a daughter, named Susanna, born to William Shakespeare, was baptized on May 26, 1583. On February 2, 1585, twins were baptized, Hamnet and Judith. (Hamnet, Shakespeare’s only son, died 11 years later.)

How Shakespeare spent the next eight years or so, until his name begins to appear in London theatre records, is not known. There are stories—given currency long after his death—of stealing deer and getting into trouble with a local magnate, Sir Thomas Lucy of Charlecote, near Stratford; of earning his living as a schoolmaster in the country; of going to London and gaining entry to the world of theatre by minding the horses of theatregoers. It has also been conjectured that Shakespeare spent some time as a member of a great household and that he was a soldier, perhaps in the Low Countries. In lieu of external evidence, such extrapolations about Shakespeare’s life have often been made from the internal “evidence” of his writings. But this method is unsatisfactory: one cannot conclude, for example, from his allusions to the law that Shakespeare was a lawyer, for he was clearly a writer who without difficulty could get whatever knowledge he needed for the composition of his plays.

William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare (Baptized April 26, 1564 – April 23, 1616) was an English poet and playwright, widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world’s preeminent dramatist. His surviving works consist of 38 plays, 154 sonnets, two long narrative poems, and several shorter poems. His plays have been translated into every major living language and are performed more often than those of any other playwright.

Shakespeare was born and lived in Stratford-upon-Avon. From 1585 until 1592 he began a successful career in London as an actor, writer, and part owner of the acting company the Lord Chamberlain’s Men. He appears to have retired to Stratford around 1613, where he died three years later. Few records of Shakespeare’s private life survive, and there has been considerable speculation about his life and prodigious literary achievements.

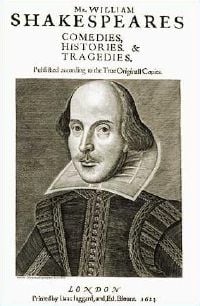

Shakespeare’s early plays were mainly comedies and histories, genres he raised to the peak of sophistication by the end of the sixteenth century. In his following phase he wrote mainly tragedies, including Hamlet, King Lear, and Macbeth, Othello. The plays are often regarded as the summit of Shakespeare’s art and among the greatest tragedies ever written. In 1623, two of his former theatrical colleagues published the First Folio, a collected edition of his dramatic works that included all but two of the plays now recognized as Shakespeare’s.

Shakespeare’s canon has achieved a unique standing in Western literature, amounting to a humanistic scripture. His insight in human character and motivation and his luminous, boundary-defying diction have influenced writers for centuries. Some of the more notable authors and poets so influenced are Samuel Taylor Coleridge, John Keats, Charles Dickens, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Herman Melville, and William Faulkner. According to Harold Bloom, Shakespeare «has been universally judged to be a more adequate representer of the universe of fact than anyone else, before or since.» [1]

Shakespeare lived during the so-called Elizabethan Settlement in which relatively moderate English Protestantism gained ascendancy. Throughout his works he explored themes of conscience, mercy, guilt, temptation, forgiveness, and the afterlife. The poet’s own religious leanings, however, are much debated. Shakespeare’s universe is governed by a recognizably Christian moral order, yet threatened and often brought to grief by tragic flaws seemingly embedded in human nature much like the heroes of Greek tragedies.

Contents

He was a respected poet and playwright in his own day, but Shakespeare’s reputation did not rise to its present heights until the nineteenth century. The Romantics, in particular, acclaimed his genius, and in the twentieth century, his work was repeatedly adopted and rediscovered by new movements in scholarship and performance. His plays remain highly popular today and are consistently performed and reinterpreted in diverse cultural and political contexts throughout the world.

William Shakespeare was born in Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire, England, in April 1564, the son of John Shakespeare, a successful tradesman and alderman, and of Mary Arden, a daughter of the gentry. Shakespeare’s baptismal record dates to April 26 of that year.

Because baptisms were performed within a few days of birth, tradition has settled on April 23 as his birthday. This date is convenient as Shakespeare died on the same day in 1616.

As the son of a prominent town official, Shakespeare was entitled to attend King Edward VI Grammar school in central Stratford, which may have provided an intensive education in Latin grammar and literature. At the age of 18, he married Anne Hathaway on November 28, 1582 at Temple Grafton, near Stratford. Hathaway, who was 25, was seven years his senior. Two neighbors of Anne posted bond that there were no impediments to the marriage. There was some haste in arranging the ceremony, presumably as Anne was three months pregnant.

After his marriage, Shakespeare left few traces in the historical record until he appeared on the London theatrical scene. The late 1580s are known as Shakespeare’s «Lost Years» because little evidence has survived to show exactly where he was or why he left Stratford for London. On May 26, 1583, Shakespeare’s first child, Susannah, was baptized at Stratford. Twin children, a son, Hamnet, and a daughter, Judith, were baptized on February 2, 1585. Hamnet died in 1596, Susanna in 1649, and Judith in 1662.

London and theatrical career

It is not known exactly when Shakespeare began writing, but contemporary allusions and records of performances show that several of his plays were on the London stage by 1592. He was well enough known in London by then to be attacked in print by the playwright Robert Greene:

…there is an upstart Crow, beautified with our feathers, that with his Tiger’s heart wrapped in a Player’s hide, supposes he is as well able to bombast out a blank verse as the best of you: and being an absolute Johannes factotum, is in his own conceit the only Shake-scene in a country. [2]

Scholars differ on the exact meaning of these words, but most agree that Greene is accusing Shakespeare of reaching above his rank in trying to match university-educated writers, such as Christopher Marlowe, Thomas Nashe and Greene himself. [3] The italicized line parodying the phrase «Oh, tiger’s heart wrapped in a woman’s hide» from Shakespeare’s Henry VI, part 3, along with the pun «Shake-scene,» identifies Shakespeare as Greene’s target.

«All the world’s a stage,

and all the men and women merely players:

they have their exits and their entrances;

and one man in his time plays many parts. «

Greene’s attack is the first recorded mention of Shakespeare in the London theatre. Biographers suggest that his career may have begun any time from the mid-1580s to just before Greene’s remarks. [4] [5] From 1594, Shakespeare’s plays were performed only by the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, a company owned by a group of players, including Shakespeare, that soon became the leading playing company in London. [6] After the death of Queen Elizabeth in 1603, the company was awarded a royal patent by the new king, James I, and changed its name to the King’s Men. The change of fortunes of the acting profession in Tudor England is noteworthy. As late as 1545 traveling actors were defined by statute as rogues and subject to arrest; largely due to Shakespeare’s writing and staging, «rogues» now enjoyed the patronage of the king, and members of the King’s Men were officially attached to the Court as Grooms of the Chamber. [7]

Shakespeare grew to maturity just as the theater was being reborn in London. London’s first theater, the Red Lion, was built in 1567, and in 1576 James Burbage (father of the famed actor Richard Burbage for whom Shakespeare would write many parts), constructed the Theater, a conscious allusion to classical amphitheaters of antiquity. [7] In 1599, a partnership of company members built their own theatre on the south bank of the Thames, which they called the Globe. In 1608, the partnership also took over the Blackfriars indoor theatre. Records of Shakespeare’s property purchases and investments indicate that the company made him a wealthy man. In 1597, he bought the second-largest house in Stratford, New Place, and in 1605, he invested in a share of the parish tithes in Stratford.

Some of Shakespeare’s plays were published in quarto editions from 1594. By 1598, his name had become a selling point and began to appear on the title pages. Shakespeare continued to act in his own and other plays after his success as a playwright. The 1616 edition of Ben Jonson’s Works names him on the cast lists for Every Man in His Humour (1598) and Sejanus, His Fall (1603). The absence of his name from the 1605 cast list for Jonson’s Volpone is taken by some scholars as a sign that his acting career was nearing its end. [8] The First Folio of 1623, however, lists Shakespeare as one of «the Principal Actors in all these Plays,» some of which were first staged after Volpone, although we cannot know for certain what roles he played. In 1610, John Davies of Hereford wrote that «good Will» played «kingly» roles. [9] In 1709, Rowe passed down a tradition that Shakespeare played the ghost of Hamlet’s father. Later traditions maintain that he also played Adam in As You Like It and the Chorus in Henry V, though scholars doubt the sources of the information.

Shakespeare divided his time between London and Stratford during his career. In 1596, the year before he bought New Place as his family home in Stratford, Shakespeare was living in the parish of St. Helen’s, Bishopsgate, north of the River Thames. He moved across the river to Southwark by 1599, the year his company constructed the Globe Theater there. By 1604, he had moved north of the river again, to an area north of St Paul’s Cathedral with many fine houses.

Later years

Shakespeare’s last two plays were written in 1613, after which he appears to have retired to Stratford. He died on April 23, 1616, at the age of 52. He remained married to Anne until his death and was survived by his two daughters, Susannah and Judith. Susannah married Dr. John Hall, but there are no direct descendants of the poet and playwright alive today.

Shakespeare is buried in the chancel of Holy Trinity Church in Stratford-upon-Avon. He was granted the honor of burial in the chancel not on account of his fame as a playwright but for purchasing a share of the tithe of the church for £440 (a considerable sum of money at the time). A bust of him placed by his family on the wall nearest his grave shows him posed in the act of writing. Each year on his claimed birthday, a new quill pen is placed in the writing hand of the bust, and he is believed to have written the epitaph on his tombstone:

Good friend, for Jesus’ sake forbear, To dig the dust enclosed here. Blest be the man that spares these stones, But cursed be he that moves my bones.

Speculations

Over the years such figures as Walt Whitman, Mark Twain, Henry James, and Sigmund Freud have expressed disbelief that the commoner from Stratford-upon-Avon actually produced the works attributed to him.

The most prominent alternative candidate for authorship of the Shakespeare canon has been Edward de Vere, the 17th Earl of Oxford, an English nobleman and intimate of Queen Elizabeth. Other alternatives include Sir Walter Raleigh, Francis Bacon, Christopher Marlowe, and even Queen Elizabeth herself. Although alternative authorship is almost universally rejected in academic circles, popular interest in the subject has continued into the twenty-first century.

A related academic question is whether Shakespeare himself wrote every word of his commonly accepted plays, given that collaboration between dramatists routinely occurred in the Elizabethan theater. Serious academic work continues to attempt to ascertain the authorship of plays and poems of the time, both those attributed to Shakespeare and others.

Shakespeare’s sexuality has also been questioned in recent years, as modern criticism has subordinated conventional literary and artistic concerns to often overtly political issues. Although 26 of Shakespeare’s sonnets are love poems addressed to a married woman (the «Dark Lady»), 126 are addressed to a young man (known as the «Fair Lord»). The amorous tone of the latter group, which focuses on the young man’s beauty, has been taken as evidence for Shakespeare’s «bisexuality,» although most critics from Shakespeare’s time to the present day interpret them as referring intense friendship, not sexual love. Another explanation is that the poems are not autobiographical, so that the «speaker» of the sonnets should not be simplistically identified with Shakespeare himself. The etiquette of chivalry and brotherly love of the time enabled Elizabethans to write about friendship in more intense language than is common today.

Works

Plays

Scholars have often categorized Shakespeare’s canon into four groupings: comedies, histories, tragedies, and romances; and his work is roughly broken into four periods. Until the mid-1590s, he wrote mainly comedies influenced by Roman and Italian models and history plays in the popular chronicle tradition. A second period began from about 1595 with the tragedy Romeo and Juliet and ended with the tragedy of Julius Caesar in 1599. During this time, he wrote what are considered his greatest comedies and histories. From about 1600 to about 1608, Shakespeare wrote most of his greatest tragedies, and from about 1608 to 1613, mainly tragicomedies or romances.

The first recorded works of Shakespeare are Richard III and the three parts of Henry VI, written in the early 1590s during a vogue for historical drama. Shakespeare’s plays are difficult to date, however, and studies of the texts suggest that Titus Andronicus, The Comedy of Errors, The Taming of the Shrew and Two Gentlemen of Verona may also belong to Shakespeare’s earliest period. His first histories, which draw heavily on the 1587 edition of Raphael Holinshed’s Chronicles of England, Scotland, and Ireland, dramatize the destructive results of weak or corrupt rule and have been interpreted as a justification for the origins of the Tudor dynasty. [10] Their composition was influenced by the works of other Elizabethan dramatists, especially Thomas Kyd and Christopher Marlowe, by the traditions of medieval drama, and by the plays of Seneca. [11] The Comedy of Errors was also based on classical models; but no source for the The Taming of the Shrew has been found, though it is related to a separate play of the same name and may have derived from a folk story. [12] Like Two Gentlemen of Verona, in which two friends appear to approve of rape, the Shrew’s story of the taming of a woman’s independent spirit by a man sometimes troubles modern critics and directors.

Shakespeare’s early classical and Italianate comedies, containing tight double plots and precise comic sequences, give way in the mid-1590s to the romantic atmosphere of his greatest comedies. A Midsummer Night’s Dream is a witty mixture of romance, fairy magic, and comic low-life scenes. Shakespeare’s next comedy, the equally romantic The Merchant of Venice, contains a portrayal of the vengeful Jewish moneylender Shylock which reflected Elizabethan views but may appear racist to modern audiences. The wit and wordplay of Much Ado About Nothing, the charming rural setting of As You Like It, and the lively merrymaking of Twelfth Night complete Shakespeare’s sequence of great comedies. After the lyrical Richard II, written almost entirely in verse, Shakespeare introduced prose comedy into the histories of the late 1590s, Henry IV, parts I and 2, and Henry V. His characters become more complex and tender as he switches deftly between comic and serious scenes, prose and poetry, and achieves the narrative variety of his mature work.

This period begins and ends with two tragedies: Romeo and Juliet, the famous romantic tragedy of sexually charged adolescence, love, and death; and Julius Caesar—based on Sir Thomas North’s 1579 translation of Plutarch’s Parallel Lives—which introduced a new kind of drama. [13] According to Shakespearean scholar James Shapiro, in Julius Caesar «the various strands of politics, character, inwardness, contemporary events, even Shakespeare’s own reflections on the act of writing, began to infuse each other». [14]

Shakespeare’s so-called «tragic period» lasted from about 1600 to 1608, though he also wrote the so-called «problem plays» Measure for Measure, Troilus and Cressida, and All’s Well That Ends Well during this time and had written tragedies before. Many critics believe that Shakespeare’s greatest tragedies represent the peak of his art. The hero of the first, Hamlet, has probably been more discussed than any other Shakespearean character, especially for his famous soliloquy «To be or not to be; that is the question.» Unlike the introverted Hamlet, whose fatal flaw is hesitation, the heroes of the tragedies that followed, Othello and King Lear, are undone by hasty errors of judgement. The plots of Shakespeare’s tragedies often hinge on such fatal errors or flaws, which overturn order and destroy the hero and those he loves. In Othello, the villain Iago stokes Othello’s sexual jealousy to the point where he murders the innocent wife who loves him. In King Lear, the old king commits the tragic error of giving up his powers, triggering scenes which lead to the murder of his daughter and the torture and blinding of the Duke of Gloucester. According to the critic Frank Kermode, «the play offers neither its good characters nor its audience any relief from its cruelty». [15] In Macbeth, the shortest and most compressed of Shakespeare’s tragedies, uncontrollable ambition incites Macbeth and his wife, Lady Macbeth, to murder the rightful king and usurp the throne, until their own guilt destroys them in turn. In this play, Shakespeare adds a supernatural element to the tragic structure. His last major tragedies, Antony and Cleopatra and Coriolanus, contain some of Shakespeare’s finest poetry and were considered his most successful tragedies by the poet and critic T. S. Eliot. [16]

In his final period, Shakespeare completed three more major plays: Cymbeline, The Winter’s Tale and The Tempest, as well as the collaboration, Pericles, Prince of Tyre. Less bleak than the tragedies, these four plays are graver in tone than the comedies of the 1590s, but they end with reconciliation and the forgiveness of potentially tragic errors. Some commentators have seen this change in mood as evidence of a more serene view of life on Shakespeare’s part, but it may merely reflect the theatrical fashion of the day. Shakespeare collaborated on two further surviving plays, Henry VIII and The Two Noble Kinsmen, probably with John Fletcher. [17]

Some of Shakespeare’s plays first appeared in print as a series of quartos, but most remained unpublished until 1623 when the posthumous First Folio was published. The traditional division of his plays into tragedies, comedies, and histories follows the logic of the First Folio. However, modern criticism has labeled some of these plays «problem plays» as they elude easy categorization and conventions, and has introduced the term «romances» for the later comedies.

There are many controversies about the exact chronology of Shakespeare’s plays. In addition, the fact that Shakespeare did not produce an authoritative print version of his plays during his life accounts for part of Shakespeare’s textual problem, often noted with his plays. This means that several of the plays have different textual versions. As a result, the problem of identifying what Shakespeare actually wrote became a major concern for most modern editions. Textual corruptions also stem from printers’ errors, compositors’ misreadings or wrongly scanned lines from the source material. Additionally, in an age before standardized spelling, Shakespeare often wrote a word several times in a different spelling, further adding to the transcribers’ confusion. Modern scholars also believe Shakespeare revised his plays throughout the years, which could lead to two existing versions of one play.

Poetry

Shakespeare’s sonnets are a collection of 154 poems that deal with such themes as love, beauty, politics, and mortality. All but two first appeared in the 1609 publication entitled Shakespeare’s Sonnets; numbers 138 («When my love swears that she is made of truth») and 144 («Two loves have I, of comfort and despair») had previously been published in a 1599 miscellany entitled The Passionate Pilgrim.

The conditions under which the sonnets were published are unclear. The 1609 text is dedicated to one «Mr. W. H.,» who is described as «the only begetter» of the poems by the publisher Thomas Thorpe. It is not known who this man was although there are many theories. In addition, it is not known whether the publication of the sonnets was authorized by Shakespeare. The poems were probably written over a period of several years.

In addition to his sonnets, Shakespeare also wrote several longer narrative poems, «Venus and Adonis,» «The Rape of Lucrece» and «A Lover’s Complaint.» These poems appear to have been written either in an attempt to win the patronage of a rich benefactor (as was common at the time) or as the result of such patronage. For example, «The Rape of Lucrece» and «Venus and Adonis» were both dedicated to Shakespeare’s patron, Henry Wriothesley, 3rd Earl of Southampton.

In addition, Shakespeare wrote the short poem “The Phoenix and the Turtle.” The anthology The Passionate Pilgrim was attributed to him upon its first publication in 1599, but in fact only five of its poems are by Shakespeare and the attribution was withdrawn in the second edition.

Shakespeare and religion

Shakespeare’s writings have achieved a stature transcending literature. They have, says Harry Levin, «been virtually canonized as humanistic scriptures, the tested residue of pragmatic wisdom, a general collection of quotable texts and usable examples.» [19] Although Shakespeare was immersed in a religiously saturated culture and themes of sin, prejudice, jealousy, conscience, mercy, guilt, temptation, forgiveness, and the afterlife appear throughout his writings, the playwright’s religious sensibilities remains notoriously problematic. In part this may owe to the political perils of professing avowedly Catholic or other doctrinally suspect sympathies in the Protestant reigns of Elizabeth I and James I.

«What were Shakespeare’s beliefs?» Aldous Huxley asked in his last published work (dictated on his deathbed). «The question is not an easy one to answer; for in the first place Shakespeare was a dramatist who made his characters express opinions which were appropriate to them, but which may not have been those of the poet. And anyhow did he himself have the same beliefs, without alteration or change or emphasis, throughout his life?» [20]

For Huxley, the poet’s essential Christianity is apparent in Measure for Measure, when the saintly Isabella reminds the self-righteous Angelo of the divine scheme of redemption and of the ethical consequences which ought to follow from its acceptance in faith. [21]

Alas, alas! Why, all the souls that were[,] were forfeit once; And He that might the vantage best have took Found out the remedy. How would you be, If He, which is the top of judgement, should But judge you as you are? O, think on that; And mercy then will breathe within your lips, Like man new-made. (Measure for Measure, Act 2, Scene 2)

Expressions of ethical Christianity are famously expressed in Portia’s appeal to the vindictive Shylock in The Merchant of Venice:

The quality of mercy is not strain’d, It droppeth as the gentle rain from heaven Upon the place beneath: it is twice blest; It blesseth him that gives and him that takes.(The Merchant Of Venice Act 4, scene 1)

The moral order, while divinely ordained, appears irreparably undone by human vices such as greed, jealousy, and a malignancy infecting the soul in such figures as Iago in Shakespeare’s Othello. Traditional Christian categories of heaven, hell, and purgatory coexist in his writings with expressions of the fundamental disorientation of the human condition:

Life’s but a walking shadow; a poor player. That struts and frets his hour upon the stage, And then is heard no more: it is a tale Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, Signifying nothing. (Macbeth, Act V, Scene 5)

For Shakespeare, at least as deduced from his writings, Christianity describes a moral order and code of conduct, more than a catalog of orthodox beliefs. The direct heir of humanists such as Petrarch, Boccaccio, Castiglione, and Montaigne, says critic Robert Grudin, Shakespeare «delighted more in presenting issues than in espousing systems, and held critical awareness, as opposed to doctrinal rectitude, to be the highest possible good.» [22]

Possible Catholic sympathies

While little direct evidence exists, circumstantial evidence suggests that Shakespeare’s family had Catholic sympathies and that he himself may have been Catholic, though this is much debated. In 1559, five years before Shakespeare’s birth, the Elizabethan Religious Settlement finally severed the Church of England from the Roman Catholic Church. In the ensuing years, extreme pressure was placed on England’s Catholics to convert to the Protestant Church of England, and recusancy laws made Catholicism illegal. Some historians maintain that in Shakespeare’s lifetime there was a substantial and widespread quiet resistance to the newly imposed faith. [23] [24] Some scholars, using both historical and literary evidence, have argued that Shakespeare was one of these recusants. [25]

There is some meager evidence that members of Shakespeare’s family were recusant Catholics. One piece of evidence is a tract, of debated authenticity, professing secret Catholicism signed by John Shakespeare, father of the poet. The tract was found in the eighteenth century in the rafters of a house which had once been John Shakespeare’s. John Shakespeare was also listed as one who did not attend church services, but this was «for feare of processe for Debtte,» according to the commissioners, not because he was a recusant. [26]

Shakespeare’s mother, Mary Arden, was a member of a conspicuous and determinedly Catholic family in Warwickshire. In 1606, William’s daughter Susannah was listed as one of the residents of Stratford refusing to take Holy Communion in a Protestant service, which may suggest Catholic sympathies. [27] It may, however, also be a sign of Puritan sympathies, which some sources have ascribed to Susannah’s sister Judith. [28] Archdeacon Richard Davies, an eighteenth century Anglican cleric, allegedly wrote of Shakespeare: «He dyed a Papyst». [29]

Four of the six schoolmasters at the grammar school during Shakespeare’s youth, King’s New School in Stratford, were Catholic sympathizers, [30] and Simon Hunt, who was likely to have been one of Shakespeare’s teachers, later became a Jesuit. [31] A fellow grammar school pupil with Shakespeare, Robert Debdale, joined the Jesuits at Douai and was later executed in England for Catholic proselytizing. [30]

The writer’s marriage to Anne Hathaway in 1582 may have been officiated, amongst other candidates, by John Frith [32] later identified by the crown as a Roman Catholic priest, although he maintained the appearance of a Protestant. [33] Some surmise Shakespeare wed in neighboring Temple Grafton rather than the Protestant Church in Stratford in order for his wedding to be performed as a Catholic sacrament. [33] Finally, one historian, Clare Asquith, has claimed that Catholic sympathies are detectable in his writing in the use of terms such as «high» when referring to Catholic characters and «low» when referring to Protestants, as well as other indicators in the text. [34]

Shakespeare’s Catholicism is by no means universally accepted. The 1914 edition of the Catholic Encyclopedia questioned not only his Catholicism, but whether «Shakespeare was not infected with the atheism, which…. was rampant in the more cultured society of the Elizabethan age.» [35] Stephen Greenblatt suspects Catholic sympathies of some kind or another in Shakespeare and his family but considers the writer to be a less than pious person with essentially worldly motives. [36] An increasing number of scholars do look to biographical and other evidence from Shakespeare’s work, such as the placement of young Hamlet as a student at Wittenberg while old Hamlet’s ghost is in purgatory, the sympathetic view of religious life («thrice blessed»), scholastic theology in The Phoenix and the Turtle, and sympathetic allusions to martyred English Jesuit St. Edmund Campion in Twelfth Night and many other matters as suggestive of a Catholic worldview. [37]

Shakepeare’s influence

On theatre

Shakespeare’s impact on modern theater cannot be overestimated. Not only did Shakespeare create some of the most admired plays in Western literature, he also transformed English theater by expanding expectations about what could be accomplished through characterization, plot, action, language and genre. [38] His poetic artistry helped raise the status of popular theater, permitting it to be admired by intellectuals as well as by those seeking pure entertainment.

Theater was changing when Shakespeare first arrived in London in the late 1580s or early 1590s. Previously, the commonest forms of popular English theater were the Tudor morality plays. These plays, which blend piety with farce and slapstick, were allegories in which the characters are personified moral attributes that validate the virtues of Godly life by prompting the protagonist to choose such a life over evil. The characters and plot situations are symbolic rather than realistic. As a child, Shakespeare would likely have been exposed to this type of play (along with mystery plays and miracle plays). Meanwhile, at the universities, academic plays were being staged based on Roman closet dramas. These plays, often performed in Latin, placed a greater emphasis on poetic dialog but emphasized lengthy speechifying over physical stage action.

By the late 1500s the popularity of morality and academic plays waned as the English Renaissance took hold, and playwrights like Thomas Kyd and Christopher Marlowe began to revolutionize theater. Their plays blended the old morality drama with academic theater to produce a new secular form. The new drama had the poetic grandeur and philosophical depth of the academic play and the bawdy populism of the moralities. However, it was more ambiguous and complex in its meanings, and less concerned with simple moral allegories. Inspired by this new style, Shakespeare took these changes to a new level, creating plays that not only resonated on an emotional level with audiences but also explored and debated the basic elements of what it meant to be human.

In plays like Hamlet, says Roland Mushat, Shakespeare «integrated characterisation with plot» in a manner that plot becomes dependent upon the development of the principal characters. [39] In Romeo and Juliet, argues Jill Levenson, Shakespeare mixed tragedy and comedy to create a new romantic tragedy genre (previous to Shakespeare, romance had not been considered a worthy topic for tragedy). [40] Finally, through his soliloquies, Shakespeare explored a character’s inner motivations and conflict, rather than, conventionally, to introduce characters, convey information, or advance the plot. [41]

Shakespeare’s plays portrayed a wide variety of emotions, and his encyclopedic insight into human nature distinguished him from any of his contemporaries. Every day life in London, which was exploding with the growth of manufacturing, gave vitality to his language. Shakespeare even used «groundlings» (lower-class, standing-room spectators) widely in his plays, which, says Boris Ford, «saved the drama from academic stiffness and preserved its essential bias towards entertainment». [42] Shakespeare’s earliest history plays and comedies portrayed the follies and achievements of kings, and «in shaping, compressing, and altering chronicles, Shakespeare gained the art of dramatic design; and in the same way he developed his remarkable insight into character, its continuity and its variation.» [42]

On literature

Shakespeare is cited as an influence on a large number of writers in succeeding centuries, including Herman Melville, Charles Dickens, Thomas Hardy, and William Faulkner. Shakespearean quotations appear throughout Dickens’ writings and many of Dickens’ titles are drawn from Shakespeare. Melville frequently used Shakespearean devices, including formal stage directions and extended soliloquies, in Moby Dick. [43] In fact, Shakespeare so influenced Melville that the novel’s main protagonist, Captain Ahab, is a classic Shakespearean tragic figure, «a great man brought down by his faults.» [44] Shakespeare has also influenced a number of English poets, especially Romantic poets who were obsessed with self-consciousness, a modern theme Shakespeare anticipated in plays such as Hamlet. Shakespeare’s writings were so influential to English poetry of the 1800s that critic George Steiner has called all English poetic dramas from Coleridge to Tennyson «feeble variations on Shakespearean themes.» [45]

Shakespeare united the three main steams of literature: verse, poetry, and drama. To the versification of the language, he imparted his eloquence and variety giving highest expressions with elasticity of language. The second, the sonnets and poetry, was bound in structure. He imparted economy and intensity to the language. In the third and the most important area, the drama, he saved the language from vagueness and vastness and infused actuality and vividness. Shakespeare’s work in prose, poetry, and drama marked the beginning of modernization of English literature by introduction of words and expressions, style and form to the language.

Shakespeare’s use of blank verse is among the most important of his influences on the way the English language was written. He used the blank verse throughout in his career, experimenting and perfecting it. The free speech rhythm gave Shakespeare more freedom for experimentation. The striking choice of words in common place blank verse, says Boris Ford, influenced «the run of the verse itself, expanding into images which eventually seem to bear significant repetition, and to form, with the presentation of character and action correspondingly developed, a more subtle and suggestive unity». [42] Expressing emotions and situations in form of a verse gave a natural flow to language with an added sense of flexibility and spontaneity.

Scholars have also identified 20,000 pieces of music linked to Shakespeare’s works. These include two operas by Giuseppe Verdi, Otello and Falstaff, whose critical standing compares with that of the source plays. Shakespeare has also inspired many painters, including the Romantics and the Pre-Raphaelites. [46] [47] The psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud drew on Shakespearean psychology, in particular that of Hamlet, for his theories of human nature. [48]

On the English language

One of Shakespeare’s greatest contributions is the introduction of vocabulary and phrases which enriched the English language, making it more colorful and expressive. Many original Shakespearean words and phrases have since become embedded in English, particularly through projects such as Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary which quoted Shakespeare more than any other writer. [49]

Shakespeare lived during an era when the English language was loose, spontaneous, and relatively unregulated. In Elizabethan England one could «happy» your friend, «malice» or «foot» your enemy, or «fall» an ax on his head. And no one was a more exuberant innovator than Shakespeare, who could «uncle me no uncle» and «out-Herod Herod.» [50] Lack of grammatical rules offered the genius of Shakespeare virtually unrestricted license to coin new terms, and the newly constructed London theaters became «the mint where new words were coined daily,» according to Globe Theater director of education Patrick Spottiswoode. [7] The theater, agrees Boris Ford, was «a constant two way exchange between learned and the popular, together producing the unique combination of racy tang and the majestic stateliness that informs the language of Shakespeare». [42] It was a two way process in which literary language gained ascendancy in the process toward standardization and descriptive popular speech enriched the literary language.

Journalist Bernard Levin summed up the lasting impact of Shakespeare on the English language with his memorable compilation of Shakespearean coinages in The Story of English: [51]

If you cannot understand my argument, and declare «It’s Greek to me,» you are quoting Shakespeare; if you claim to be more sinned against than sinning, you are quoting Shakespeare; if you recall your salad days, you are quoting Shakespeare; if you act more in sorrow than in anger, if your wish is father to the thought, if your property has vanished into thin air, you are quoting Shakespeare; if you have ever refused to budge an inch or suffered from green-eyed jealousy, if you have played fast and loose, if you have been tongue-tied, a tower of strength, hoodwinked or in a pickle, if you have knitted your brows, made a virtue of necessity, insisted on fair play, slept not one wink, stood on ceremony, danced attendance (on your lord and master), laughed yourself into stitches, had short shrift, cold comfort or too much of a good thing, if you have seen better days or lived in a fool’s paradise—why, be that as it may, the more fool you, for it is a foregone conclusion that you are (as good luck would have it) quoting Shakespeare; if you think it is early days and clear out bag and baggage, if you think it is high time and that is the long and short of it, if you believe that the game is up and that truth will out even if it involves your own flesh and blood, if you lie low till the crack of doom because you suspect foul play, if you have your teeth set on edge (at one fell swoop) without rhyme or reason, then—to give the devil his due—if the truth were known (for surly you have a tongue in your head) you are quoting Shakespeare; even if you bid me good riddance and send me packing, if you wish I was dead as a door-nail, if you think I am an eyesore, a laughing stock, the devil incarnate, a stony-hearted villain, bloody-minded or a blinkin idiot, then—by Jove! O Lord! Tut, tut! for goodness’ sake! what the dickens! but me no buts—it is all one to me, for you are quoting Shakespeare.

Reputation

Shakespeare’s reputation has grown considerably through the years. During his lifetime and shortly after his death, Shakespeare was well-regarded but not considered the supreme poet of his age. He was included in some contemporary lists of leading poets, but he lacked the stature of Edmund Spenser or Philip Sidney. After the Interregnum stage ban of 1642–1660, the new Restoration theater companies had the previous generation of playwrights as the mainstay of their repertory, most of all the phenomenally popular Beaumont and Fletcher team, but also Ben Jonson and Shakespeare. As with other older playwrights, Shakespeare’s plays were mercilessly adapted by later dramatists for the Restoration stage with little of the reverence that would later develop.

Beginning in the late seventeenth century, Shakespeare began to be considered the supreme English-language playwright and, to a lesser extent, poet. Initially this reputation focused on Shakespeare as a dramatic poet, to be studied on the printed page rather than in the theater. By the early nineteenth century, though, Shakespeare began hitting peaks of fame and popularity. During this time, theatrical productions of Shakespeare provided spectacle and melodrama for the masses and were extremely popular. Romantic critics such as Samuel Taylor Coleridge then raised admiration for Shakespeare to adulation or ‘bardolatry’, in line with the Romantic reverence for the poet as prophet and genius. In the middle to late nineteenth century, Shakespeare also became an emblem of English pride and a «rallying-sign,» as Thomas Carlyle wrote in 1841, for the whole British Empire.

Shakespeare’s continued supremacy, wrote critic Harold Bloom in 1999, is an empirical certainty: the Stratford playwright «has been universally judged to be a more adequate representer of the universe of fact than anyone else, before him or since. This judgment has been dominant at least since the mid-eighteenth century; it has been staled by repetition, yet it remains merely true. … He extensively informs the language we speak, his principal characters have become our mythology, and he, rather than his involuntary follower Freud, is our psychologist.» [52]

This reverence has of course provoked a negative reaction. In the twenty-first century most inhabitants of the English-speaking world encounter Shakespeare at school at a young age, and there is a common association of his work with boredom and incomprehension. At the same time, Shakespeare’s plays remain more frequently staged than the works of any other playwright and are frequently adapted into film.

List of works

Notes

References

External links

All links retrieved October 10, 2020.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/william-shakespeare-portrait-of-william-shakespeare-1564-1616-chromolithography-after-hombres-y-mujeres-celebres-1877-barcelona-spain-118154739-57d712c63df78c583373bb00.jpg)