How many poems has william shakespeare written

How many poems has william shakespeare written

Shakespeare’s Poems

Learn about Shakespeare’s famous sonnets and other poems

Shakespeare is widely recognised as the greatest English poet the world has ever known. Not only were his plays mainly written in verse, but he also penned 154 sonnets, two long narrative poems and a few other minor poems. Today he has become a symbol of poetry and writing internationally.

For the bard of all bards was a Warwickshire Bard

Shakespeare’s Sonnets

154 of Shakespeare’s sonnets are included in the volume Shakespeare’s Sonnets, published by Thomas Thorpe in 1609. They are followed by the long poem ‘A Lover’s Complaint’, which first appeared in that same volume after the sonnets. Six additional sonnets appear in his plays Romeo and Juliet, Henry V and Love’s Labour’s Lost.

Shakespeare’s sonnets generally focus on the themes of love and life. The first 126 are directed to a young man whom the speaker urges to marry, but this man then becomes the object of the speaker’s desire. The last 28 sonnets are addressed to an older woman, the so-called ‘dark lady’, who causes both desire and loathing in the speaker. However, several of the sonnets, if taken individually, may appear gender-neutral, as in the well-known ‘Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?’ from Sonnet 18. The linear, sequential reading of the poems is also debatable, since it is unclear if Shakespeare intended for the sonnets to be published in this way.

While he may have experimented with the form earlier, Shakespeare most likely began writing sonnets seriously around 1592. What is now known as the Shakespearian sonnet is the English sonnet form Shakespeare popularised: fourteen lines of iambic pentameter (a ten-syllable pattern of alternating unaccented and accented syllables). The rhyme scheme breaks the poem into three quatrains (four lines each) and a couplet (two lines).

Shakespeare changed the world of poetry not only with his prolific use of this new form, but also in deviating from what was standard content. Instead of romantic fiction, written to an unattainable ideal woman, Shakespeare writes to a young man and a dark woman, who may or may not be attainable, and who arouse conflicting feelings in the speaker.

Shakespeare’s Narrative Poems

Shakespeare published two long poems, among his earliest successes: Venus and Adonis in 1593 and The Rape of Lucrece in 1594. These poems were dedicated to his patron the Earl of Southampton.

Venus and Adonis was Shakespeare’s first-published work. Modelled after the Roman poet Ovid, it is a re-telling of the classical myth: Venus, the goddess of love, falls for a young mortal who dies after being attacked by a wild boar. Shakespeare interprets the myth comically as well as tragically, for Adonis continually resists Venus’s desire. The poem is considered an experiment in delicate eroticism.

The Rape of Lucrece is also a long poem based on Ovid, but rather more serious, and based on history rather than myth. The story is the rape of Lucretia, wife of Collatinus, by Tarquinius Sextus, son of the Roman king Tarquinius Superbus. Devastated and filled with shame, Lucretia stabs herself to death. The poem comments on the problems of masculine violence and institutionalised attitudes towards feminine chastity.

Another of Shakespeare’s poems ‘The Phoenix and Turtle’ was commissioned to be included in a collection by Robert Chester called Love’s Martyr (1601). The Oxford edition of the complete works (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1986) also includes as Shakespeare’s various poems, some songs, and epitaphs.

How many poems has william shakespeare written

Making the status quo

William Shakespeare is known for 150 sonnets. A sonnet is composed of fourteen lines with a rhyming scheme. The Bard has shown that poem composition can be done in such a manner while still maintaining the integrity of the thought. Where most people can expel a thought that rhymes (one need only to think of nursery rhymes like “Mary had a little lamb”), William Shakespeare has done so with careful attention to the subject matter and the overall flow and thought of the poem. In his very first sonnet we can see how his ability to do so has rightly earned him the esteemed position of the status quo.

The rhyme scheme here would be A,B,A,C,B,D,B,D,E,F,E,F,G,G. This is a commonly used methodology used in sonnets today.In writing it is referred to as the English or the Shakespearean sonnet. If looking at the sound of the sentences there is a distinct verbal rhythm apart from the ending rhyme that flows from the poem. Oration of this sonnet will reveal this.

It is all about love

Compared to the diversity of some of the later poets, one may think that William Shakespeare’s poems are a bit lacking in their subject scope. However, one would do well to consider the time era from whence these poems were written. During this era, literary professionals were hard pressed to make a living. Plays (for which William Shakespeare is best known) were looked upon more as a hobby than a professional career and so the money for such works was not substantial to live off of. Poems were considered to be something for the nobles and upper society. Being that parchment was also considered to be a sacred material at that time (mainly due to the scarcity to secure large quantities at one time), the lines of the poems written had to be catered specifically to sell. What better to sell than a love sonnet during the Elizabethan Era?

The Two Unknowns

Unknown to a great many, are the two narrative poems of William Shakespeare. These two poems were written around the same time period (1593 and 1594) of his career. It could be concluded that these two poems were composed as a test. Being that there are no other narratives it can also be concluded that William Shakespeare did not see the merit in composing such lengthy poems and therefore focused on where money could be made. It is only in the later years after an artist is gone that the cultural world seems to embrace the artistry of one’s work. It would appear that such rings true with these two poems.

Venus and Adonis

The earlier of the two poems, William Shakespeare truly shows that he can present a story in poetic form. The poem was constructed for as he put it “so noble a god-father”, the earl of Southampton. Again, we see that there is the strong story of love and conflict which tends to radiate throughout his work. However, another key aspect of William Shakespeare’s work can be seen here and that is his use of the mythological. Where Venus is a common mythological deity, one will find that other such beings are introduced not only in his sonnets and poems but also within his plays. With such, here lies the tie with the ancient muses and the Elizabethan poets.

The Rape of Lucrece

Not uncommon to William Shakespeare, this poem focuses on a murder and the pursuit of lover. One can see the clear association with his play Hamlet (written around 1590) as well as Macbeth (written around 1603) within this work. Being as the poem was written early in his career, one may conclude that this poem served as a starting point for the later plays. It would be foolish for the seasoned reader not to conclude that such associations with these later works were deliberately constructed from the format and content of this work.

The Bard

Those which are looking for a poet to aspire to would do well to follow the writings of William Shakespeare. The sonnets allow the poet to practice tactful word play while the narrative poems provide us with an exercise in intricate storytelling.

Readers of poetry would be greatly benefited from reading the sonnets of Shakespeare. Many of the “modern” poets have read and in some cases mimicked his work very closely. As a serious poet, one cannot abandon the building blocks for which the poetic area was built. Being that William Shakespeare has earned the title “The Bard”, we would all be wise to listen with earnestness to the words he has written.

The poems of William Shakespeare

Shakespeare seems to have wanted to be a poet as much as he sought to succeed in the theatre. His plays are wonderfully and poetically written, often in blank verse. And when he experienced a pause in his theatrical career about 1592–94, the plague having closed down much theatrical activity, he wrote poems. Venus and Adonis (1593) and The Rape of Lucrece (1594) are the only works that Shakespeare seems to have shepherded through the printing process. Both owe a good deal to Ovid, the Classical poet whose writings Shakespeare encountered repeatedly in school. These two poems are the only works for which he wrote dedicatory prefaces. Both are to Henry Wriothesley, earl of Southampton. This young man, a favourite at court, seems to have encouraged Shakespeare and to have served for a brief time at least as his sponsor. The dedication to the second poem is measurably warmer than the first. An unreliable tradition supposes that Southampton gave Shakespeare the stake he needed to buy into the newly formed Lord Chamberlain’s acting company in 1594. Shakespeare became an actor-sharer, one of the owners in a capitalist enterprise that shared the risks and the gains among them. This company succeeded brilliantly; Shakespeare and his colleagues, including Richard Burbage, John Heminge, Henry Condell, and Will Sly, became wealthy through their dramatic presentations.

Plays of the middle and late years

Romantic comedies

In the second half of the 1590s, Shakespeare brought to perfection the genre of romantic comedy that he had helped to invent. A Midsummer Night’s Dream (c. 1595–96), one of the most successful of all his plays, displays the kind of multiple plotting he had practiced in The Taming of the Shrew and other earlier comedies. The overarching plot is of Duke Theseus of Athens and his impending marriage to an Amazonian warrior, Hippolyta, whom Theseus has recently conquered and brought back to Athens to be his bride. Their marriage ends the play. They share this concluding ceremony with the four young lovers Hermia and Lysander, Helena and Demetrius, who have fled into the forest nearby to escape the Athenian law and to pursue one another, whereupon they are subjected to a complicated series of mix-ups. Eventually all is righted by fairy magic, though the fairies are no less at strife. Oberon, king of the fairies, quarrels with his Queen Titania over a changeling boy and punishes her by causing her to fall in love with an Athenian artisan who wears an ass’s head. The artisans are in the forest to rehearse a play for the forthcoming marriage of Theseus and Hippolyta. Thus four separate strands or plots interact with one another. Despite the play’s brevity, it is a masterpiece of artful construction.

The use of multiple plots encourages a varied treatment of the experiencing of love. For the two young human couples, falling in love is quite hazardous; the long-standing friendship between the two young women is threatened and almost destroyed by the rivalries of heterosexual encounter. The eventual transition to heterosexual marriage seems to them to have been a process of dreaming, indeed of nightmare, from which they emerge miraculously restored to their best selves. Meantime the marital strife of Oberon and Titania is, more disturbingly, one in which the female is humiliated until she submits to the will of her husband. Similarly, Hippolyta is an Amazon warrior queen who has had to submit to the authority of a husband. Fathers and daughters are no less at strife until, as in a dream, all is resolved by the magic of Puck and Oberon. Love is ambivalently both an enduring ideal relationship and a struggle for mastery in which the male has the upper hand.

The Merchant of Venice (c. 1596–97) uses a double plot structure to contrast a tale of romantic wooing with one that comes close to tragedy. Portia is a fine example of a romantic heroine in Shakespeare’s mature comedies: she is witty, rich, exacting in what she expects of men, and adept at putting herself in a male disguise to make her presence felt. She is loyally obedient to her father’s will and yet determined that she shall have Bassanio. She triumphantly resolves the murky legal affairs of Venice when the men have all failed. Shylock, the Jewish moneylender, is at the point of exacting a pound of flesh from Bassanio’s friend Antonio as payment for a forfeited loan. Portia foils him in his attempt in a way that is both clever and shystering. Sympathy is uneasily balanced in Shakespeare’s portrayal of Shylock, who is both persecuted by his Christian opponents and all too ready to demand an eye for an eye according to ancient law. Ultimately Portia triumphs, not only with Shylock in the court of law but in her marriage with Bassanio.

Much Ado About Nothing (c. 1598–99) revisits the issue of power struggles in courtship, again in a revealingly double plot. The young heroine of the more conventional story, derived from Italianate fiction, is wooed by a respectable young aristocrat named Claudio who has won his spurs and now considers it his pleasant duty to take a wife. He knows so little about Hero (as she is named) that he gullibly credits the contrived evidence of the play’s villain, Don John, that she has had many lovers, including one on the evening before the intended wedding. Other men as well, including Claudio’s senior officer, Don Pedro, and Hero’s father, Leonato, are all too ready to believe the slanderous accusation. Only comic circumstances rescue Hero from her accusers and reveal to the men that they have been fools. Meantime, Hero’s cousin, Beatrice, finds it hard to overcome her skepticism about men, even when she is wooed by Benedick, who is also a skeptic about marriage. Here the barriers to romantic understanding are inner and psychological and must be defeated by the good-natured plotting of their friends, who see that Beatrice and Benedick are truly made for one another in their wit and candour if they can only overcome their fear of being outwitted by each other. In what could be regarded as a brilliant rewriting of The Taming of the Shrew, the witty battle of the sexes is no less amusing and complicated, but the eventual accommodation finds something much closer to mutual respect and equality between men and women.

Rosalind, in As You Like It (c. 1598–1600), makes use of the by-now familiar device of disguise as a young man in order to pursue the ends of promoting a rich and substantial relationship between the sexes. As in other of these plays, Rosalind is more emotionally stable and mature than her young man, Orlando. He lacks formal education and is all rough edges, though fundamentally decent and attractive. She is the daughter of the banished Duke who finds herself obliged, in turn, to go into banishment with her dear cousin Celia and the court fool, Touchstone. Although Rosalind’s male disguise is at first a means of survival in a seemingly inhospitable forest, it soon serves a more interesting function. As “Ganymede,” Rosalind befriends Orlando, offering him counseling in the affairs of love. Orlando, much in need of such advice, readily accepts and proceeds to woo his “Rosalind” (“Ganymede” playing her own self) as though she were indeed a woman. Her wryly amusing perspectives on the follies of young love helpfully puncture Orlando’s inflated and unrealistic “Petrarchan” stance as the young lover who writes poems to his mistress and sticks them up on trees. Once he has learned that love is not a fantasy of invented attitudes, Orlando is ready to be the husband of the real young woman (actually a boy actor, of course) who is presented to him as the transformed Ganymede-Rosalind. Other figures in the play further an understanding of love’s glorious foolishness by their various attitudes: Silvius, the pale-faced wooer out of pastoral romance; Phoebe, the disdainful mistress whom he worships; William, the country bumpkin, and Audrey, the country wench; and, surveying and commenting on every imaginable kind of human folly, the clown Touchstone and the malcontent traveler Jaques.

Twelfth Night (c. 1600–02) pursues a similar motif of female disguise. Viola, cast ashore in Illyria by a shipwreck and obliged to disguise herself as a young man in order to gain a place in the court of Duke Orsino, falls in love with the duke and uses her disguise as a cover for an educational process not unlike that given by Rosalind to Orlando. Orsino is as unrealistic a lover as one could hope to imagine; he pays fruitless court to the Countess Olivia and seems content with the unproductive love melancholy in which he wallows. Only Viola, as “Cesario,” is able to awaken in him a genuine feeling for friendship and love. They become inseparable companions and then seeming rivals for the hand of Olivia until the presto change of Shakespeare’s stage magic is able to restore “Cesario” to her woman’s garments and thus present to Orsino the flesh-and-blood woman whom he has only distantly imagined. The transition from same-sex friendship to heterosexual union is a constant in Shakespearean comedy. The woman is the self-knowing, constant, loyal one; the man needs to learn a lot from the woman. As in the other plays as well, Twelfth Night neatly plays off this courtship theme with a second plot, of Malvolio’s self-deception that he is desired by Olivia—an illusion that can be addressed only by the satirical devices of exposure and humiliation.

The Merry Wives of Windsor (c. 1597–1601) is an interesting deviation from the usual Shakespearean romantic comedy in that it is set not in some imagined far-off place like Illyria or Belmont or the forest of Athens but in Windsor, a solidly bourgeois village near Windsor Castle in the heart of England. Uncertain tradition has it that Queen Elizabeth wanted to see Falstaff in love. There is little, however, in the way of romantic wooing (the story of Anne Page and her suitor Fenton is rather buried in the midst of so many other goings-on), but the play’s portrayal of women, and especially of the two “merry wives,” Mistress Alice Ford and Mistress Margaret Page, reaffirms what is so often true of women in these early plays, that they are good-hearted, chastely loyal, and wittily self-possessed. Falstaff, a suitable butt for their cleverness, is a scapegoat figure who must be publicly humiliated as a way of transferring onto him the human frailties that Windsor society wishes to expunge.

Completion of the histories

Concurrent with his writing of these fine romantic comedies, Shakespeare also brought to completion (for the time being, at least) his project of writing 15th-century English history. After having finished in 1589–94 the tetralogy about Henry VI, Edward IV, and Richard III, bringing the story down to 1485, and then circa 1594–96 a play about John that deals with a chronological period (the 13th century) that sets it quite apart from his other history plays, Shakespeare turned to the late 14th and early 15th centuries and to the chronicle of Richard II, Henry IV, and Henry’s legendary son Henry V. This inversion of historical order in the two tetralogies allowed Shakespeare to finish his sweep of late medieval English history with Henry V, a hero king in a way that Richard III could never pretend to be.

Richard II (c. 1595–96), written throughout in blank verse, is a sombre play about political impasse. It contains almost no humour, other than a wry scene in which the new king, Henry IV, must adjudicate the competing claims of the Duke of York and his Duchess, the first of whom wishes to see his son Aumerle executed for treason and the second of whom begs for mercy. Henry is able to be merciful on this occasion, since he has now won the kingship, and thus gives to this scene an upbeat movement. Earlier, however, the mood is grim. Richard, installed at an early age into the kingship, proves irresponsible as a ruler. He unfairly banishes his own first cousin, Henry Bolingbroke (later to be Henry IV), whereas the king himself appears to be guilty of ordering the murder of an uncle. When Richard keeps the dukedom of Lancaster from Bolingbroke without proper legal authority, he manages to alienate many nobles and to encourage Bolingbroke’s return from exile. That return, too, is illegal, but it is a fact, and, when several of the nobles (including York) come over to Bolingbroke’s side, Richard is forced to abdicate. The rights and wrongs of this power struggle are masterfully ambiguous. History proceeds without any sense of moral imperative. Henry IV is a more capable ruler, but his authority is tarnished by his crimes (including his seeming assent to the execution of Richard), and his own rebellion appears to teach the barons to rebel against him in turn. Henry eventually dies a disappointed man.

The dying king Henry IV must turn royal authority over to young Hal, or Henry, now Henry V. The prospect is dismal both to the dying king and to the members of his court, for Prince Hal has distinguished himself to this point mainly by his penchant for keeping company with the disreputable if engaging Falstaff. The son’s attempts at reconciliation with the father succeed temporarily, especially when Hal saves his father’s life at the battle of Shrewsbury, but (especially in Henry IV, Part 2) his reputation as wastrel will not leave him. Everyone expects from him a reign of irresponsible license, with Falstaff in an influential position. It is for these reasons that the young king must publicly repudiate his old companion of the tavern and the highway, however much that repudiation tugs at his heart and the audience’s. Falstaff, for all his debauchery and irresponsibility, is infectiously amusing and delightful; he represents in Hal a spirit of youthful vitality that is left behind only with the greatest of regret as the young man assumes manhood and the role of crown prince. Hal manages all this with aplomb and goes on to defeat the French mightily at the Battle of Agincourt. Even his high jinks are a part of what is so attractive in him. Maturity and position come at a great personal cost: Hal becomes less a frail human being and more the figure of royal authority.

Thus, in his plays of the 1590s, the young Shakespeare concentrated to a remarkable extent on romantic comedies and English history plays. The two genres are nicely complementary: the one deals with courtship and marriage, while the other examines the career of a young man growing up to be a worthy king. Only at the end of the history plays does Henry V have any kind of romantic relationship with a woman, and this one instance is quite unlike courtships in the romantic comedies: Hal is given the Princess of France as his prize, his reward for sturdy manhood. He takes the lead in the wooing scene in which he invites her to join him in a political marriage. In both romantic comedies and English history plays, a young man successfully negotiates the hazardous and potentially rewarding paths of sexual and social maturation.

Biography of William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare works marked the completion of the process of creation of English language and culture, brought closure to the European Renaissance.

Born: 26 April 1564

Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire, England

Playwright, poet, actor

His plays are still an integral part of the basic repertoire of theaters all over the world. In the age of new technologies, almost all Shakespeare’s plays were cinematized.

Biography of William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare was born in Stratford-on-Avon, England, in the 1564. The date of his birth is not known. It is generally accepted to believe it was the 23 of April, but the day of his baptism is set in veracity: it was the 26th of April. His father was a well-to-do craftsman respected in the city, and the mother was a representative of an ancient Saxon family.

In the 1592-1594, the theaters of London were closed in a connection with a plague epidemic. The vast number of plays, poems and other works written then made Shakespeare a well- known writer. In the 1594, when the theaters opened, Shakespeare entered into a new drama group– a so called group of a servant of a Lord Chamberlain named in the honor of its patron. Shakespeare was not only an actor, but a shareholder.

The event of the 1599 was significant: it was the creation of the theater “Globe”. Thus, Shakespeare became not only an actor, but also the chief playwright and one of the owners.

In the same lifespan, Shakespeare became a nobleman, acquired the second big house in the city of Stratford.

Approximately in the 1612, Shakespeare, whose career developed very successfully, unexpectedly for everyone, left the capital and went back to Stratford, to his family.

On the 3d of April, 1616 one of the greatest playwrights of the world died; he was buried on the outskirts of the hometown in the church of the Holy Trinity.

Creative Work of William Shakespeare

It is well- know, that in the 1592, Shakespeare was already the author of the historical chronicle “Henry VI”.

In the period of the 1592-1594, Shakespeare wrote plays and elegant, sensual poems. For Shakespeare, the works of the period 1593-1600 (“Much Ado About Nothing”, “The Taming of the Shrew”, “A Midsummer Night’s Dream”) expressed the thought about perception of a person, first of all, according to the inner world. This idea evolves more remotely, comparing to harsh reality. Thus, Shakespeare’s tragedy “Romeo and Juliet” contains the bright sense of love together with the bitterness of insurmountable obstacles. “Hamlet”, “Macbeth”, “King Lear”, “Othello” were written by Shakespeare in the period of the 1601 — 1608.

For Shakespeare, the comedies are the way to write a clear, jolly, light and, in addition, a profound composition.

William Shakespeare poems

William Shakespeare poems (154) are of different subjects, they express various feelings. The clear chronology of writing of poems (=sonnets) by William Shakespeare was not kept in the biography. Each sonnet represents a verse of fourteen lines, where the following rhyme is accepted: abab cdcd efef gg. The series of sonnets is conditionally divided into twelve theme groups, which can be generally expressed as follows:

Shakespeare’s first works were written in ordinary language not separating the playwright from a crowd of the same writers. To avoid plainness in his compositions, Shakespeare loaded them with metaphors, literally threading them on each other. This prevented him from revealing images of characters.

However, soon the poet came to his traditional style and got used to it. The use of a blank verse (written with iambic pentameter) became his standard. But even it is distinguished by its quality, if the initial works are compared to subsequent ones.

Writing with focus on theatrical performances is the peculiarity of Shakespeare’s style. Enjambment, unusual constructions and length of sentences are used in his works on a large scale. Sometimes the playwright offered the spectator to finish reflection about the completion of a phrase on his own, putting a long pause insertion in his work.

How did william shakespeare die?

William Shakespeare death: 23 April 1616 in Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire, England

April 23, 1616 – William Shakespeare dies at Stradford-upon-Avon on his birthday. Shakespeare’s testament from March 15, 1616, was signed in illegible handwriting, on the basis of which some researchers believe that he was at that time seriously ill. Shakespeare died at the age of 52 for unknown reasons.

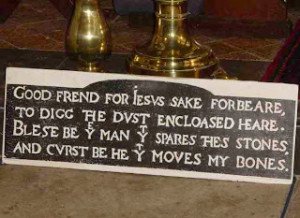

Where is shakespeare buried?

Three days later Shakespeare’s body was buried under the altar of the parish church of the Holy Trinity in his hometown of Stratford-upon-Avon. William’s funeral cannot be called pompous, unlike the funeral of such playwrights as Francis Beaumont and Ben Johnson, who were buried in Westminster Abbey with great honors.

Every year thousands of people visit his grave.

The lines are written on his tombstone.

To digg the dvst encloased heare.

Bleste be ye man yt spares thes stones,

And cvrst be he yt moves my bones.

The scientists asked permission to exhume the playwright’s body in the hope of establishing how he died. Modern equipment will allow to establish all the nuances of the state of health and lifestyle of the great writer. Paleontologists sent an official statement to the Anglican church. The decision to exhume the body of Shakespeare has not yet been made.

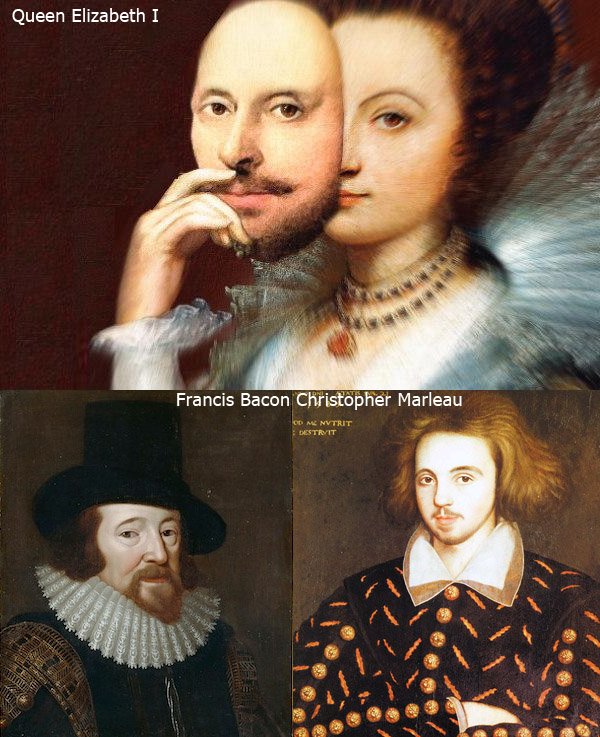

Did Shakespearereally write his own plays?

There is an opinion that under the name of Shakespeare there is a completely different historical face. Some researchers argue that Shakespeare did not write his plays at all. More than 50 candidates were considered to be authors of Shakespeare’s works.

The main “pretender” to the authorship of Shakespeare’s plays is the Oxford Count Edward de Vere, who stopped publishing in 1593, while Shakespeare declared himself in 1594.

The pseudonym “Shakespeare” was not chosen by chance. The family coat of arms of de Vere depicts a knight with a spear in his hand.

Almost all of Shakespeare’s plays are a vivid parody of the mores of the court, so, with a pseudonym, the Count could continue to create. In addition, Edward de Vere could not publicly declare himself a playwright: in those days writing for the people was not appropriate for aristocrats.

He died in 1604, it is not known where his grave is, researchers claim that his works continued to be published by his family under a pseudonym until 1616 (just this year Shakespeare died).

In 1975, the British Encyclopedia confirmed this hypothesis, stating: “Edward de Vere is the most likely pretender to the authorship of Shakespeare’s plays.”

Also as the alleged authors were called Francis Bacon, Christopher Marleau, and even Queen Elizabeth I herself…

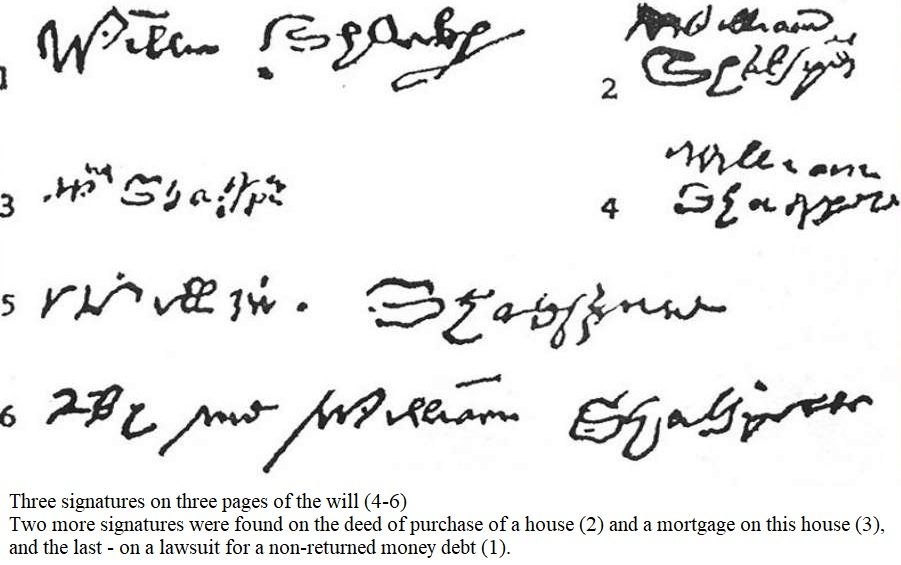

Signature Shakespeare

In the four saved documents, six signatures, possibly made by William Shakespeare’s hand, were found. The name of the playwright can only be disassembled in part. In addition, it is not always written in the same way. Some experts believe that Shakespeare possibly did not sign it himself. Lawyers could have done for it for him.

Three signatures on three pages of the will. Two more signatures were found on the deed of purchase of a house and a mortgage on this house, and the last – on a lawsuit for a non-returned money debt.

If you look at the signature, you can see that the clumsy and scattered letters were written with great strain. In addition, the signatures were badly like one another, as if they were written by different people.

Shakespeare and the Bible

Quotes from the Bible. One of the sides, which includes the Shakespearean question, is the literacy of William. Works created by Shakespeare often include quotes from biblical texts. His mother might have introduced him to them. However, there is no evidence that this woman was literate. The fact that Shakespeare knew the Bible raises the question of his education.

Were Shakespeare and his daughters literate?

Not a single manuscript personally written by him was saved. Suzanne, his daughter was able to write her name. But there is no proof that she was educated. Perhaps her writing skills were limited to this. Another daughter of William, Judith, who was particularly close to Shakespeare, put a sign instead of a signature. Therefore, she was illiterate. It is not known why William did not give his children the opportunity to get an education.

How many words did Shakespeare create?

The author shows excellent knowledge of Roman and Greek classics, as well as French, Spanish and Italian literature. It is possible that he knew Italian, French and Spanish. The playwright’s vocabulary is very rich. An educated Englishman in our time rarely uses more than 4,000 words in a speech. An English poet John Milton’s vocabulary was estimated to 8000 words. And in the works of Shakespeare, according to experts, there is no less than 21 thousand words.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, Shakespeare introduced almost three thousand new words into English. Shakespeare’s works contain 2035! words that had never appeared in print before. Countless number of amazing in the elegance and depth of the phrases belong to the pen of Shakespeare.

Shakespeare’s Wife, Anne Hathaway

Anna died on August 6, 1623, and was buried in the church of the Holy Trinity next to her husband. The inscription on the tombstone says that she died “at the age of 67”. This is the only remaining indication of the date of her birth.

Was Shakespeare gay?

Despite the marriage of Shakespeare and the presence of children, the researchers of his works raise different opinions about his sexual orientation, suggesting his attraction to men, while referring to some of his plays, as well as the fact that Shakespeare lived for a long time in London, while his wife was in Stratford with their children.

The best metropolitan friend of the playwright was Henry Reesley, the third Earl of Southampton, who used to wear women’s clothing and use everyday make-up.

Earring in the left ear

Various scholars believe that Shakespeare liked to wear a gold ring earring in his left ear, which gave him a creative and bohemian look. This earring can be seen on Chandos portrait, one of the most popular images of the playwright.

Popular poems by William Shakespeare

How did William Shakespeare die?

Just a month before his death, Shakespeare signed a will, where he describes himself as being in “perfect health.” Researches haven’t found a reliable contemporary document explaining the cause of his death. 50 years later, the vicar of Stratford wrote in his notebook that Shakespeare died as a result of “fever” caused by drinking too hard during a meeting with two friends of his.

Where did William Shakespeare die?

The world’s greatest dramatist died in Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire, England.

Video

William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare Poems

All the world’s a stage,

And all the men and women merely players;

They have their exits and their entrances,

And one man in his time plays many parts,

.

Over hill, over dale,

Thorough bush, thorough brier,

Over park, over pale,

Thorough flood, thorough fire!

.

Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?

Thou art more lovely and more temperate.

Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May,

And summer’s lease hath all too short a date.

.

Fear no more the heat o’ the sun;

Nor the furious winter’s rages,

Thou thy worldly task hast done,

Home art gone, and ta’en thy wages;

.

O mistress mine, where are you roaming?

O stay and hear! your true-love’s coming

That can sing both high and low;

Trip no further, pretty sweeting,

.

Blow, blow, thou winter wind

Thou art not so unkind

As man’s ingratitude;

Thy tooth is not so keen,

.

FROM off a hill whose concave womb reworded

A plaintful story from a sistering vale,

My spirits to attend this double voice accorded,

And down I laid to list the sad-tuned tale;

Ere long espied a fickle maid full pale,

Tearing of papers, breaking rings a-twain,

Storming her world with sorrow’s wind and rain.

.

Hark! hark! the lark at heaven’s gate sings,

And Phoebus ‘gins arise,

His steeds to water at those springs

On chalic’d flowers that lies;

.

TELL me where is Fancy bred,

Or in the heart or in the head?

How begot, how nourished?

Reply, reply.

.

Let me not to the marriage of true minds

Admit impediments. Love is not love

Which alters when it alteration finds,

Or bends with the remover to remove.

.

ROSES, their sharp spines being gone,

Not royal in their smells alone,

But in their hue;

Maiden pinks, of odour faint,

.

COME away, come away, death,

And in sad cypres let me be laid;

Fly away, fly away, breath;

I am slain by a fair cruel maid.

.

Crabbed Age and Youth

Cannot live together:

Youth is full of pleasance,

Age is full of care;

.

Full fathom five thy father lies;

Of his bones are coral made;

Those are pearls that were his eyes:

Nothing of him that doth fade

.

OVER hill, over dale,

Thorough bush, thorough brier,

Over park, over pale,

Thorough flood, thorough fire,

.

Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?

Thou art more lovely and more temperate.

Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May,

And summer’s lease hath all too short a date.

.

HARK! hark! the lark at heaven’s gate sings,

And Phoebus ‘gins arise,

His steeds to water at those springs

On chaliced flowers that lies;

.

When my love swears that she is made of truth

I do believe her, though I know she lies,

That she might think me some untutored youth,

Unlearnèd in the world’s false subtleties.

.

YOU spotted snakes with double tongue,

Thorny hedgehogs, be not seen;

Newts and blind-worms, do no wrong;

Come not near our fairy queen.

.

When icicles hang by the wall

And Dick the shepherd blows his nail

And Tom bears logs into the hall,

And milk comes frozen home in pail,

.

William Shakespeare Biography

William Shakespeare was a renowned English poet, actor, and playwright born in 1564 in Stratford-upon-Avon. His birthday is most commonly celebrated on 23 April. His date of death is unknown which is also believed to be the date he died in 1616. He is buried in the sanctuary of the parish church, Holy Trinity. Shakespeare was a prolific writer during the English Renaissance or the Early Modern Period of British theater. Shakespeare’s plays and poems are perhaps his most enduring legacy, but they are not all he wrote.

William Shakespeare’s Life Short Summary

He is often called England’s national poet and the “Bard of Avon”. His works, including some consist of about 38 plays, collaborations, two long narrative poems, 154 sonnets, and several other poems. His plays have been translated and performed all around the world. He began a successful career in London as an actor, playwright, and part owner of the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, afterwards known as the King’s Men, between 1585 and 1592. At the age of 49, he retired to Stratford, where he died three years later. There are few records of Shakespeare’s personal life, and there has been much conjecture regarding his physical appearance, sexuality, religious views, and whether or not the works attributed to him were authored by others. He then wrote mainly tragedies until about 1608, including Hamlet, King Lear, Othello, and Macbeth, considered some of the finest works in the English language. In his last phase, he wrote tragicomedies, also known as romances, and collaborated with other playwrights. Shakespeare was a respected poet and playwright in his own day, but his reputation did not rise to its present heights until the 19th century. The Romantics, in particular, acclaimed Shakespeare’s genius, and the Victorians worshipped Shakespeare with a reverence that George Bernard Shaw called «bardolatry». In the 20th century, his work was repeatedly adopted and rediscovered by new movements in scholarship and performance. His plays remain highly popular today and are constantly studied, performed and reinterpreted in diverse cultural and political contexts throughout the world.

William Shakespeare’s Wife Anne Hathaway Who is?

Later Years and Death

Rowe was the first biographer to pass down the tradition that Shakespeare retired to Stratford some years before his death; but retirement from all work was uncommon at that time; and Shakespeare continued to visit London. In 1612 he was called as a witness in a court case concerning the marriage settlement of Mountjoy’s daughter, Mary. In March 1613 he bought a gatehouse in the former Blackfriars priory; and from November 1614 he was in London for several weeks with his son-in-law, John Hall. After 1606–1607, Shakespeare wrote fewer plays, and none are attributed to him after 1613. His last three plays were collaborations, probably with John Fletcher, who succeeded him as the house playwright for the King’s Men. Shakespeare died on 23 April 1616 and was survived by his wife and two daughters. Susanna had married a physician, John Hall, in 1607, and Judith had married Thomas Quiney, a vintner, two months before Shakespeare’s death. In his will, Shakespeare left the bulk of his large estate to his elder daughter Susanna. The terms instructed that she pass it down intact to «the first son of her body». The Quineys had three children, all of whom died without marrying. The Halls had one child, Elizabeth, who married twice but died without children in 1670, ending Shakespeare’s direct line. Shakespeare’s will scarcely mentions his wife, Anne, who was probably entitled to one third of his estate automatically. He did make a point, however, of leaving her «my second best bed», a bequest that has led to much speculation. Some scholars see the bequest as an insult to Anne, whereas others believe that the second-best bed would have been the matrimonial bed and therefore rich in significance. Shakespeare was buried in the chancel of the Holy Trinity Church two days after his death. The epitaph carved into the stone slab covering his grave includes a curse against moving his bones, which was carefully avoided during restoration of the church in 2008: Good frend for Iesvs sake forbeare, To digg the dvst encloased heare. Bleste be ye man yt spares thes stones, And cvrst be he yt moves my bones. Modern spelling: «Good friend, for Jesus’ sake forbear,» «To dig the dust enclosed here.» «Blessed be the man that spares these stones,» «And cursed be he who moves my bones.» Sometime before 1623, a funerary monument was erected in his memory on the north wall, with a half-effigy of him in the act of writing. Its plaque compares him to Nestor, Socrates, and Virgil. In 1623, in conjunction with the publication of the First Folio, the Droeshout engraving was published. Shakespeare has been commemorated in many statues and memorials around the world, including funeral monuments in Southwark Cathedral and Poets’ Corner in Westminster Abbey. Plays Most playwrights of the period typically collaborated with others at some point, and critics agree that Shakespeare did the same, mostly early and late in his career. Some attributions, such as Titus Andronicus and the early history plays, remain controversial, while The Two Noble Kinsmen and the lost Cardenio have well-attested contemporary documentation. Textual evidence also supports the view that several of the plays were revised by other writers after their original composition. The first recorded works of Shakespeare are Richard III and the three parts of Henry VI, written in the early 1590s during a vogue for historical drama. Shakespeare’s plays are difficult to date, however, and studies of the texts suggest that Titus Andronicus, The Comedy of Errors, The Taming of the Shrew and The Two Gentlemen of Verona may also belong to Shakespeare’s earliest period. His first histories, which draw heavily on the 1587 edition of Raphael Holinshed’s Chronicles of England, Scotland, and Ireland, dramatise the destructive results of weak or corrupt rule and have been interpreted as a justification for the origins of the Tudor dynasty. The early plays were influenced by the works of other Elizabethan dramatists, especially Thomas Kyd and Christopher Marlowe, by the traditions of medieval drama, and by the plays of Seneca. The Comedy of Errors was also based on classical models, but no source for The Taming of the Shrew has been found, though it is related to a separate play of the same name and may have derived from a folk story. Like The Two Gentlemen of Verona, in which two friends appear to approve of rape, the Shrew’s story of the taming of a woman’s independent spirit by a man sometimes troubles modern critics and directors. Shakespeare’s early classical and Italianate comedies, containing tight double plots and precise comic sequences, give way in the mid-1590s to the romantic atmosphere of his greatest comedies. A Midsummer Night’s Dream is a witty mixture of romance, fairy magic, and comic lowlife scenes. Shakespeare’s next comedy, the equally romantic Merchant of Venice, contains a portrayal of the vengeful Jewish moneylender Shylock, which reflects Elizabethan views but may appear derogatory to modern audiences. The wit and wordplay of Much Ado About Nothing, the charming rural setting of As You Like It, and the lively merrymaking of Twelfth Night complete Shakespeare’s sequence of great comedies. After the lyrical Richard II, written almost entirely in verse, Shakespeare introduced prose comedy into the histories of the late 1590s, Henry IV, parts 1 and 2, and Henry V. His characters become more complex and tender as he switches deftly between comic and serious scenes, prose and poetry, and achieves the narrative variety of his mature work. This period begins and ends with two tragedies: Romeo and Juliet, the famous romantic tragedy of sexually charged adolescence, love, and death; and Julius Caesar—based on Sir Thomas North’s 1579 translation of Plutarch’s Parallel Lives—which introduced a new kind of drama. According to Shakespearean scholar James Shapiro, in Julius Caesar «the various strands of politics, character, inwardness, contemporary events, even Shakespeare’s own reflections on the act of writing, began to infuse each other». In the early 17th century, Shakespeare wrote the so-called «problem plays» Measure for Measure, Troilus and Cressida, and All’s Well That Ends Well and a number of his best known tragedies. Many critics believe that Shakespeare’s greatest tragedies represent the peak of his art. The titular hero of one of Shakespeare’s most famous tragedies, Hamlet, has probably been discussed more than any other Shakespearean character, especially for his famous soliloquy «To be or not to be; that is the question». Unlike the introverted Hamlet, whose fatal flaw is hesitation, the heroes of the tragedies that followed, Othello and King Lear, are undone by hasty errors of judgement. The plots of Shakespeare’s tragedies often hinge on such fatal errors or flaws, which overturn order and destroy the hero and those he loves. In Othello, the villain Iago stokes Othello’s sexual jealousy to the point where he murders the innocent wife who loves him. In King Lear, the old king commits the tragic error of giving up his powers, initiating the events which lead to the torture and blinding of the Earl of Gloucester and the murder of Lear’s youngest daughter Cordelia. According to the critic Frank Kermode, «the play offers neither its good characters nor its audience any relief from its cruelty». In Macbeth, the shortest and most compressed of Shakespeare’s tragedies, uncontrollable ambition incites Macbeth and his wife, Lady Macbeth, to murder the rightful king and usurp the throne, until their own guilt destroys them in turn. In this play, Shakespeare adds a supernatural element to the tragic structure. His last major tragedies, Antony and Cleopatra and Coriolanus, contain some of Shakespeare’s finest poetry and were considered his most successful tragedies by the poet and critic T. S. Eliot. In his final period, Shakespeare turned to romance or tragicomedy and completed three more major plays: Cymbeline, The Winter’s Tale and The Tempest, as well as the collaboration, Pericles, Prince of Tyre. Less bleak than the tragedies, these four plays are graver in tone than the comedies of the 1590s, but they end with reconciliation and the forgiveness of potentially tragic errors. Some commentators have seen this change in mood as evidence of a more serene view of life on Shakespeare’s part, but it may merely reflect the theatrical fashion of the day. Shakespeare collaborated on two further surviving plays, Henry VIII and The Two Noble Kinsmen, probably with John Fletcher. Performances It is not clear for which companies Shakespeare wrote his early plays. The title page of the 1594 edition of Titus Andronicus reveals that the play had been acted by three different troupes. After the plagues of 1592–3, Shakespeare’s plays were performed by his own company at The Theatre and the Curtain in Shoreditch, north of the Thames. Londoners flocked there to see the first part of Henry IV, Leonard Digges recording, «Let but Falstaff come, Hal, Poins, the rest. and you scarce shall have a room».] When the company found themselves in dispute with their landlord, they pulled The Theatre down and used the timbers to construct the Globe Theatre, the first playhouse built by actors for actors, on the south bank of the Thames at Southwark. The Globe opened in autumn 1599, with Julius Caesar one of the first plays staged. Most of Shakespeare’s greatest post-1599 plays were written for the Globe, including Hamlet, Othello and King Lear. After the Lord Chamberlain’s Men were renamed the King’s Men in 1603, they entered a special relationship with the new King James. Although the performance records are patchy, the King’s Men performed seven of Shakespeare’s plays at court between 1 November 1604 and 31 October 1605, including two performances of The Merchant of Venice. After 1608, they performed at the indoor Blackfriars Theatre during the winter and the Globe during the summer. The indoor setting, combined with the Jacobean fashion for lavishly staged masques, allowed Shakespeare to introduce more elaborate stage devices. In Cymbeline, for example, Jupiter descends «in thunder and lightning, sitting upon an eagle: he throws a thunderbolt. The ghosts fall on their knees.» The actors in Shakespeare’s company included the famous Richard Burbage, William Kempe, Henry Condell and John Heminges. Burbage played the leading role in the first performances of many of Shakespeare’s plays, including Richard III, Hamlet, Othello, and King Lear. The popular comic actor Will Kempe played the servant Peter in Romeo and Juliet and Dogberry in Much Ado About Nothing, among other characters. He was replaced around the turn of the 16th century by Robert Armin, who played roles such as Touchstone in As You Like It and the fool in King Lear. In 1613, Sir Henry Wotton recorded that Henry VIII «was set forth with many extraordinary circumstances of pomp and ceremony». On 29 June, however, a cannon set fire to the thatch of the Globe and burned the theatre to the ground, an event which pinpoints the date of a Shakespeare play with rare precision. Textual Sources In 1623, John Heminges and Henry Condell, two of Shakespeare’s friends from the King’s Men, published the First Folio, a collected edition of Shakespeare’s plays. It contained 36 texts, including 18 printed for the first time. Many of the plays had already appeared in quarto versions—flimsy books made from sheets of paper folded twice to make four leaves. No evidence suggests that Shakespeare approved these editions, which the First Folio describes as «stol’n and surreptitious copies». Alfred Pollard termed some of them «bad quartos» because of their adapted, paraphrased or garbled texts, which may in places have been reconstructed from memory. Where several versions of a play survive, each differs from the other. The differences may stem from copying or printing errors, from notes by actors or audience members, or from Shakespeare’s own papers. In some cases, for example Hamlet, Troilus and Cressida and Othello, Shakespeare could have revised the texts between the quarto and folio editions. In the case of King Lear, however, while most modern additions do conflate them, the 1623 folio version is so different from the 1608 quarto, that the Oxford Shakespeare prints them both, arguing that they cannot be conflated without confusion. William Shakespeare’s Poems In 1593 and 1594, when the theatres were closed because of plague, Shakespeare published two narrative poems on erotic themes, Venus and Adonis and The Rape of Lucrece. He dedicated them to Henry Wriothesley, Earl of Southampton. In Venus and Adonis, an innocent Adonis rejects the sexual advances of Venus; while in The Rape of Lucrece, the virtuous wife Lucrece is raped by the lustful Tarquin. Influenced by Ovid’s Metamorphoses, the poems show the guilt and moral confusion that result from uncontrolled lust. Both proved popular and were often reprinted during Shakespeare’s lifetime. A third narrative poem, A Lover’s Complaint, in which a young woman laments her seduction by a persuasive suitor, was printed in the first edition of the Sonnets in 1609. Most scholars now accept that Shakespeare wrote A Lover’s Complaint. Critics consider that its fine qualities are marred by leaden effects. The Phoenix and the Turtle, printed in Robert Chester’s 1601 Love’s Martyr, mourns the deaths of the legendary phoenix and his lover, the faithful turtle dove. In 1599, two early drafts of sonnets 138 and 144 appeared in The Passionate Pilgrim, published under Shakespeare’s name but without his permission. Sonnets Published in 1609, the Sonnets were the last of Shakespeare’s non-dramatic works to be printed. Scholars are not certain when each of the 154 sonnets was composed, but evidence suggests that Shakespeare wrote sonnets throughout his career for a private readership. Even before the two unauthorised sonnets appeared in The Passionate Pilgrim in 1599, Francis Meres had referred in 1598 to Shakespeare’s «sugred Sonnets among his private friends». Few analysts believe that the published collection follows Shakespeare’s intended sequence. He seems to have planned two contrasting series: one about uncontrollable lust for a married woman of dark complexion (the «dark lady»), and one about conflicted love for a fair young man (the «fair youth»). It remains unclear if these figures represent real individuals, or if the authorial «I» who addresses them represents Shakespeare himself, though Wordsworth believed that with the sonnets «Shakespeare unlocked his heart». The 1609 edition was dedicated to a «Mr. W.H.», credited as «the only begetter» of the poems. It is not known whether this was written by Shakespeare himself or by the publisher, Thomas Thorpe, whose initials appear at the foot of the dedication page; nor is it known who Mr. W.H. was, despite numerous theories, or whether Shakespeare even authorised the publication. Critics praise the Sonnets as a profound meditation on the nature of love, sexual passion, procreation, death, and time. Style Shakespeare’s first plays were written in the conventional style of the day. He wrote them in a stylised language that does not always spring naturally from the needs of the characters or the drama. The poetry depends on extended, sometimes elaborate metaphors and conceits, and the language is often rhetorical—written for actors to declaim rather than speak. The grand speeches in Titus Andronicus, in the view of some critics, often hold up the action, for example; and the verse in The Two Gentlemen of Verona has been described as stilted. Soon, however, Shakespeare began to adapt the traditional styles to his own purposes. The opening soliloquy of Richard III has its roots in the self-declaration of Vice in medieval drama. At the same time, Richard’s vivid self-awareness looks forward to the soliloquies of Shakespeare’s mature plays. No single play marks a change from the traditional to the freer style. Shakespeare combined the two throughout his career, with Romeo and Juliet perhaps the best example of the mixing of the styles. By the time of Romeo and Juliet, Richard II, and A Midsummer Night’s Dream in the mid-1590s, Shakespeare had begun to write a more natural poetry. He increasingly tuned his metaphors and images to the needs of the drama itself. Shakespeare’s standard poetic form was blank verse, composed in iambic pentameter. In practice, this meant that his verse was usually unrhymed and consisted of ten syllables to a line, spoken with a stress on every second syllable. The blank verse of his early plays is quite different from that of his later ones. It is often beautiful, but its sentences tend to start, pause, and finish at the end of lines, with the risk of monotony. Once Shakespeare mastered traditional blank verse, he began to interrupt and vary its flow. This technique releases the new power and flexibility of the poetry in plays such as Julius Caesar and Hamlet. Shakespeare uses it, for example, to convey the turmoil in Hamlet’s mind: Sir, in my heart there was a kind of fighting That would not let me sleep. Methought I lay Worse than the mutines in the bilboes. Rashly— And prais’d be rashness for it—let us know Our indiscretion sometimes serves us well. Hamlet, Act 5, Scene 2, 4–8 After Hamlet, Shakespeare varied his poetic style further, particularly in the more emotional passages of the late tragedies. The literary critic A. C. Bradley described this style as «more concentrated, rapid, varied, and, in construction, less regular, not seldom twisted or elliptical». In the last phase of his career, Shakespeare adopted many techniques to achieve these effects. These included run-on lines, irregular pauses and stops, and extreme variations in sentence structure and length. In Macbeth, for example, the language darts from one unrelated metaphor or simile to another: «was the hope drunk/ Wherein you dressed yourself?» (1.7.35–38); «. pity, like a naked new-born babe/ Striding the blast, or heaven’s cherubim, hors’d/ Upon the sightless couriers of the air. » (1.7.21–25). The listener is challenged to complete the sense. The late romances, with their shifts in time and surprising turns of plot, inspired a last poetic style in which long and short sentences are set against one another, clauses are piled up, subject and object are reversed, and words are omitted, creating an effect of spontaneity. Shakespeare combined poetic genius with a practical sense of the theatre. Like all playwrights of the time, he dramatised stories from sources such as Plutarch and Holinshed. He reshaped each plot to create several centres of interest and to show as many sides of a narrative to the audience as possible. This strength of design ensures that a Shakespeare play can survive translation, cutting and wide interpretation without loss to its core drama. As Shakespeare’s mastery grew, he gave his characters clearer and more varied motivations and distinctive patterns of speech. He preserved aspects of his earlier style in the later plays, however. In Shakespeare’s late romances, he deliberately returned to a more artificial style, which emphasised the illusion of theatre. Influence Shakespeare’s work has made a lasting impression on later theatre and literature. In particular, he expanded the dramatic potential of characterisation, plot, language, and genre. Until Romeo and Juliet, for example, romance had not been viewed as a worthy topic for tragedy. Soliloquies had been used mainly to convey information about characters or events; but Shakespeare used them to explore characters’ minds. His work heavily influenced later poetry. The Romantic poets attempted to revive Shakespearean verse drama, though with little success. Critic George Steiner described all English verse dramas from Coleridge to Tennyson as «feeble variations on Shakespearean themes.» Shakespeare influenced novelists such as Thomas Hardy, William Faulkner, and Charles Dickens. The American novelist Herman Melville’s soliloquies owe much to Shakespeare; his Captain Ahab in Moby-Dick is a classic tragic hero, inspired by King Lear. Scholars have identified 20,000 pieces of music linked to Shakespeare’s works. These include two operas by Giuseppe Verdi, Otello and Falstaff, whose critical standing compares with that of the source plays. Shakespeare has also inspired many painters, including the Romantics and the Pre-Raphaelites. The Swiss Romantic artist Henry Fuseli, a friend of William Blake, even translated Macbeth into German. The psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud drew on Shakespearean psychology, in particular that of Hamlet, for his theories of human nature. In Shakespeare’s day, English grammar, spelling and pronunciation were less standardised than they are now, and his use of language helped shape modern English. Samuel Johnson quoted him more often than any other author in his A Dictionary of the English Language, the first serious work of its type. Expressions such as «with bated breath» (Merchant of Venice) and «a foregone conclusion» (Othello) have found their way into everyday English speech. Critical Reputation Shakespeare was not revered in his lifetime, but he received his share of praise. In 1598, the cleric and author Francis Meres singled him out from a group of English writers as «the most excellent» in both comedy and tragedy. And the authors of the Parnassus plays at St John’s College, Cambridge, numbered him with Chaucer, Gower and Spenser. In the First Folio, Ben Jonson called Shakespeare the «Soul of the age, the applause, delight, the wonder of our stage», though he had remarked elsewhere that «Shakespeare wanted art». Between the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660 and the end of the 17th century, classical ideas were in vogue. As a result, critics of the time mostly rated Shakespeare below John Fletcher and Ben Jonson. Thomas Rymer, for example, condemned Shakespeare for mixing the comic with the tragic. Nevertheless, poet and critic John Dryden rated Shakespeare highly, saying of Jonson, «I admire him, but I love Shakespeare». For several decades, Rymer’s view held sway; but during the 18th century, critics began to respond to Shakespeare on his own terms and acclaim what they termed his natural genius. A series of scholarly editions of his work, notably those of Samuel Johnson in 1765 and Edmond Malone in 1790, added to his growing reputation. By 1800, he was firmly enshrined as the national poet. In the 18th and 19th centuries, his reputation also spread abroad. Among those who championed him were the writers Voltaire, Goethe, Stendhal and Victor Hugo. During the Romantic era, Shakespeare was praised by the poet and literary philosopher Samuel Taylor Coleridge; and the critic August Wilhelm Schlegel translated his plays in the spirit of German Romanticism. In the 19th century, critical admiration for Shakespeare’s genius often bordered on adulation. «That King Shakespeare,» the essayist Thomas Carlyle wrote in 1840, «does not he shine, in crowned sovereignty, over us all, as the noblest, gentlest, yet strongest of rallying signs; indestructible». The Victorians produced his plays as lavish spectacles on a grand scale. The playwright and critic George Bernard Shaw mocked the cult of Shakespeare worship as «bardolatry». He claimed that the new naturalism of Ibsen’s plays had made Shakespeare obsolete. The modernist revolution in the arts during the early 20th century, far from discarding Shakespeare, eagerly enlisted his work in the service of the avant-garde. The Expressionists in Germany and the Futurists in Moscow mounted productions of his plays. Marxist playwright and director Bertolt Brecht devised an epic theatre under the influence of Shakespeare. The poet and critic T. S. Eliot argued against Shaw that Shakespeare’s «primitiveness» in fact made him truly modern. Eliot, along with G. Wilson Knight and the school of New Criticism, led a movement towards a closer reading of Shakespeare’s imagery. In the 1950s, a wave of new critical approaches replaced modernism and paved the way for «post-modern» studies of Shakespeare. By the eighties, Shakespeare studies were open to movements such as structuralism, feminism, New Historicism, African American studies, and queer studies. Speculation about Shakespeare Authorship Main article: Shakespeare authorship question Around 150 years after Shakespeare’s death, doubts began to be expressed about the authorship of the works attributed to him. Proposed alternative candidates include Francis Bacon, Christopher Marlowe, and Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford. Several «group theories» have also been proposed. Only a small minority of academics believe there is reason to question the traditional attribution, but interest in the subject, particularly the Oxfordian theory of Shakespeare authorship, continues into the 21st century. Religion Some scholars claim that members of Shakespeare’s family were Catholics, at a time when Catholic practice was against the law. Shakespeare’s mother, Mary Arden, certainly came from a pious Catholic family. The strongest evidence might be a Catholic statement of faith signed by John Shakespeare, found in 1757 in the rafters of his former house in Henley Street. The document is now lost, however, and scholars differ as to its authenticity. In 1591 the authorities reported that John Shakespeare had missed church «for fear of process for debt», a common Catholic excuse. In 1606 the name of William’s daughter Susanna appears on a list of those who failed to attend Easter communion in Stratford. Scholars find evidence both for and against Shakespeare’s Catholicism in his plays, but the truth may be impossible to prove either way. Sexuality Few details of Shakespeare’s sexuality are known. At 18, he married the 26-year-old Anne Hathaway, who was pregnant. Susanna, the first of their three children, was born six months later on 26 May 1583. Over the centuries some readers have posited that Shakespeare’s sonnets are autobiographical, and point to them as evidence of his love for a young man. Others read the same passages as the expression of intense friendship rather than sexual love. The 26 so-called «Dark Lady» sonnets, addressed to a married woman, are taken as evidence of heterosexual liaisons. Portraiture There is no written description of Shakespeare’s physical appearance and no evidence that he ever commissioned a portrait, so the Droeshout engraving, which Ben Jonson approved of as a good likeness, and his Stratford monument provide the best evidence of his appearance. From the 18th century, the desire for authentic Shakespeare portraits fuelled claims that various surviving pictures depicted Shakespeare. That demand also led to the production of several fake portraits, as well as misattributions, repaintings and relabelling of portraits of other people.)

The Best Poem Of William Shakespeare

All The World’s A Stage

All the world’s a stage,

And all the men and women merely players;

They have their exits and their entrances,

And one man in his time plays many parts,

His acts being seven ages. At first, the infant,

Mewling and puking in the nurse’s arms.

Then the whining schoolboy, with his satchel

And shining morning face, creeping like snail

Unwillingly to school. And then the lover,

Sighing like furnace, with a woeful ballad

Made to his mistress’ eyebrow. Then a soldier,

Full of strange oaths and bearded like the pard,

Jealous in honor, sudden and quick in quarrel,

Seeking the bubble reputation

Even in the cannon’s mouth. And then the justice,

In fair round belly with good capon lined,

With eyes severe and beard of formal cut,

Full of wise saws and modern instances;

And so he plays his part. The sixth age shifts

Into the lean and slippered pantaloon,

With spectacles on nose and pouch on side;

His youthful hose, well saved, a world too wide

For his shrunk shank, and his big manly voice,

Turning again toward childish treble, pipes

And whistles in his sound. Last scene of all,

That ends this strange eventful history,

Is second childishness and mere oblivion,

Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything.