How much money или how many money

How much money или how many money

Понятное правило использования much-many в английском языке. Примеры употребления, упражнения с ответами

Они не являются взаимозаменяемыми: в одних случаях вам понадобится только much, а в других – только many. Здесь всё зависит от самого слова, к которому будет относиться much или many. Давайте разбираться, что к чему!

Разница между many и much

Местоимение many употребляется в тех случаях, когда оно относится к предметам (одушевленным или неодушевленным), которые можно посчитать. Слова, обозначающие такие предметы, называются исчисляемыми существительными.

используем many ( так как их можно посчитать)

Местоимение Much употребляется только с существительными, которые нельзя сосчитать, то есть с неисчисляемыми существительными.

используем much ( так как их нельзя сосчитать. Much означает большое количество чего-либо.)

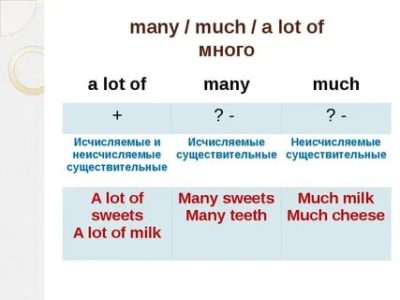

Смотрим таблицу, которая вам наглядно покажет разницу употребления Much, Many

| Much/Little (много/мало) | Many/Few (много/мало) | A lot of / Plenty of (много) |

|---|---|---|

| Неисчисляемые существительные | Исчисляемые существительные | Исчисляемые и несчисляемые существительные |

| How much money have you got? – Как много у тебя денег? There is little ink left in my pen. – В моей ручке осталось немного чернил. | I have many friends. – У меня много друзей. He has got few best friends. – У него несколько (немного) лучших друзей. | There is a lot of sugar there. – Там много сахара. There are plenty of plants in the garden. – В саду много растений. |

Вопросительные предложения

Отрицательные предложения

MUCH or MANY or A LOT OF?

Упражнения на тему much / many:

Упражнениe 1. Используйте much или many для выражения Сколько…?.

Упражнение 2. Переведите предложения на английский язык, используя much, many, a little, a few, little, few, a lot of

Упражнение 3. Используйте much или many.

Do you drink ________coffee? I like reading. I read _________ books. We have _______ lessons of English this year. I can’t remember _______ from this text. Do you learn _______ new English words every day? We haven’t got ________ bread. I can’t spend ________ money on toys.

Ответы

Упражнение 1.

Упражнение 2.

Упражнение 3.

Do you drink much coffee? I like reading. I read many books. We have many lessons of English this year. I can’t remember much from this text. Do you learn many new English words every day? We haven’t got much bread. I can’t spend much money on toys.

How much money или how many money

Many, much, few, a few, little, a lot of, plenty of

С исчисляемыми существительными, т.е. то, что можно посчитать – употребляются many (много), few (мало), a few (несколько).

Например:

They have many books at home – У них дома есть много книг.

She doesn’t have many friends – У нее нет много друзей.

Many of them came to the party – Многие из них пришли на вечеринку.

How many days did you spend there? – Сколько дней ты провел там?

She has few friends – У нее мало друзей.

Few people know about this – Немногие знают об этом.

He spent a few hours to learn this – Он потратил несколько часов, чтобы выучить это.

I have just a few apples – У меня есть всего несколько яблок.

С неисчисляемыми существительными, т.е. то, что нельзя посчитать – употребляются much (много), little (мало), a little (немного)

Например:

They earn much money – Они зарабатывают много денег.

Don’t put so much sugar in my coffee – Не клади в мой кофе так много сахара.

We have little time, hurry up – У нас мало времени, поторопись.

Could you add milk, just a little – Добавь молоко, только немного.

How much time do you need? – Сколько времени тебе нужно?

С исчисляемыми и неисчисляемыми существительными употребляются a lot of (много), lots of (много), plenty of (много). Они заменяют much и many. Иногда, когда вы не знаете, является ли то или иное существительное исчисляемым или нет, можно смело использовать a lot of, plenty of, lots of.

Например:

They have a lot of books at home – У них дома есть много книг.

Every month they make a lot of money – Каждый месяц они зарабатывают много денег.

We have lots of time to finish this – У нас уйма времени, чтобы закончить это.

She has plenty of new friends – У нее много новых друзей.

Если в предложении есть наречие very (очень), too (слишком), so (так), то после них употребляется только much или many.

Например:

They have so many friends here – У них так много друзей здесь.

He drinks too much beer – Он пьет слишком много пива.

Когда пишется many а когда much

В каких случаях пишется a lot of. much и many в английском языке

Смысловые и грамматические особенности употребления few, little, much, many, a lot of.

В своей речи мы часто употребляем такие слова, как «мало» или «немного», «несколько» или «много». Тем самым, мы пытаемся указать на не совсем конкретное количество чего-либо. Употребление в английском языке much, many, a lot of, few, little иногда вызывает затруднение. Однако данные местоимения очень часто встречаются в речи и, от их правильного употребления, зависит смысл фразы.

Понять и правильно использовать их в речи довольно легко, если соблюдать следующие правила английской грамматики и следовать нижеописанным шагам.

Шаг 1. Определяем значение местоимения (перевод слова)

Much Many >много

Few

Little >мало

Шаг 2. Определяем группу существительного, к которому оно относится

Все существительные можно разделить на исчисляемые (те, которые можно посчитать: ручка – 2 ручки, pen – 2 pens) и неисчисляемые(сахар, вода; sugar, water)

Шаг 3. Выбираем подходящее местоимение

Разница между few, little, much, many, несмотря на идентичный перевод данных языковых пар, заключается именно в употреблении последующего существительного.

Так, much и little используется с неисчисляемыми:

much work- много работы; much salt – много соли;

little money – мало денег;little sugar – мало сахара;

I haven’t much work today. — У меня сегодня не много работы.

My mother gave me little money, I can’t buy it. — Мне мама дала мало денег, я не могу это купить(мало,недостаточно).

Many и few ставиться перед исчисляемыми:

many pencils – много карандашей; many books – много книг; few friends – мало друзей; few cars – мало машин;

Have you got many books about animals? У тебя много книг о животных?

Unfortunately, he has few friends. К сожалению, у него мало друзей (мало, недостаточно)

Таким образом, определив группу существительного (исчисляемое или неисчисляемое), можно легко выбрать нужное местоимение.

Обратите внимание, что a lot of (lots of, plenty of разговорные формы) употребляется и перед исчисляемыми, и перед неисчисляемыми существительными. Эта «палочка-выручалочка» всегда поможет передать значение «много», если вам трудно определить к какой группе отнести слово.

He spent a lot of money.Он потратил много денег.

He has got a lot of financial problems.У него много финансовых проблем.

Примечание:Plenty of передает значение больше, чем необходимо; чересчур много.

Have some more to eat. — No, thank you. I’ve had plenty of.

Покушай еще. Нет, спасибо. Я уже достаточно съел.

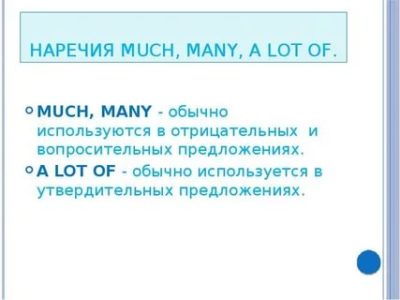

Шаг 4. Определяем тип предложения (утвердительное, вопросительное, отрицательное)

Much, many — лучше использовать в отрицательных или вопросительных предложениях. A lot of— также передающее значение «много» — желательно употребить в утвердительных.

Однако, стоит быть внимательным, такие словосочетания как too much, as much, so much, very much или how much используются и в утвердительных фразах.

Важно заметить, что английская грамматика гласит, что местоимение much может передавать значение очень, значительно, гораздо или намного.

He didn’t put much sugar into the tea. (отрицательное) Он не добавил в чай много сахара.

Have you got many books? (вопросительное) У тебя много книг?

I can’t eat this soup. There’s too much salt. Я не могу есть этот суп. В нем слишком много соли.

He did it much sooner. – Он сделал это намного быстрее.

Так как, little, fewимеют немного негативное значение (мало, недостаточно, хотелось бы больше), то их употребление лучше звучит в отрицательных предложениях.

Если вы хотите передать значение мало, но достаточно, чуть-чуть, всего лишь немного, то поставьте неопределенный артикль «а» перед ними- a few, a little. Такое сочетание целесообразнее использовать в утвердительных выражениях, так как оно несёт позитивный оттенок.

Обратите внимание, использование фразы only a little или only a few отражает легкое недовольство (немного, я хочу больше).

We’ve got little time. — У нас мало времени.Tom is not friendly. He has got few friends. — Том не дружелюбен. У него мало друзей.Have you got any time to talk? Yes, a little.- У тебя есть время поговорить? Да, немного.When did you visit granny? A few days ago. — Когда ты навещал бабушку? Несколько дней назад (не так давно).

The house was very small. There were only a few rooms. — Это был небольшой дом. В нем только несколько комнат.

Как видите, ничего сложного в употреблении местоимений much, many, few, little нет. Главное, внимательно смотрите на стоящее рядом существительное и тип предложения, и ваша речь будет грамотной и понятной.

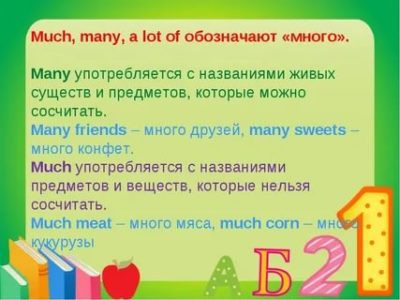

В русском языке мы говорим: много денег, много конфет, много усилий, много машин и т.д. Во всех этих словосочетаниях мы используем одно слово. В английском языке есть слова much, many и a lot, которые переводятся как «много». Но используются они по-разному.

Произношение и перевод:

Many [ˈmeni] / [мени] — много

Значение слова:

Большое количество предметов или людей

Употребление:

Мы используем manyможем посчитать. Например: много людей, много деревьев, много книг, много лет.

Bill doesn’t have many friends.

У Била не много друзей.

Did he win many competitions?

Он выиграл много соревнований?

Произношение и перевод:

Much [ˈmʌtʃ] / [мач] — много

Значение слова:

Большое количество

Употребление:

Мы используем much, когда говорим о чем-то, что не можем сосчитать. Например: много воды, много времени, много денег, много работы.

You drink too much coffee.

Ты пьешь слишком много кофе.

Правила английского языка. 15 правил, которые необходимо знать

Привет друзья. Грамматика английского языка, снабженная многочисленными примерами, помогающими лучше ее освоить. Все грамматические правила изложены очень понятным языком. Как начинающие изучать английский язык, так и продолжающие, найдут здесь для себя много полезной информации. Английская грамматика станет для вас намного проще.

Эти правила необходимо знать!

Итак, дорогие читатели, сейчас вы познакомитесь с основными правилами английского из разных разделов языка. Они касаются и грамматики, и речи, и синтаксиса и многого другого.

Правило № 1

После модальных глаголов частица to не употребляется. Мы говорим:

Правило № 2

Нельзя употреблять определенный/неопределенный артикль с местоимением:

Правило № 3

Наречия английского языка (на вопрос «как?») образуются по схеме: прилагательное + окончание ly:

Правило № 4

Используйте Present Simple, после союзов if, as soon as, before, when, till, until, after, in case в предложениях времени и условия, относящихся к будущему:

Правило № 5

Порядок слов в английском предложении таков:

Подлежащее + сказуемое + прямое дополнение + косвенное дополнение + обстоятельство

Subject + predicate + direct object + indirect object + adverbal modifier

В русском предложении допускаются вольности, и в нем нет определенного порядка слов, все зависит от эмоции, вложенной в него. В английском предложении все четко и строго.

Правило № 6

Фразовые глаголы (глагол + предлог) английского языка имеют свое, отдельное значение и свой перевод. Например:

To look — смотреть; to look for — искать

To put — ставить, класть; to put on — надеть

Правило № 7

Самое общее правило для определенного и неопределенного артиклей английского языка: неопределенный артикль ставится там, где ничего не известно о предмете; определенный артикль употребляется там, где что-то известно о предмете.

Правило № 8

Окончание —ed характерно для прошедших времен только правильных глаголов. У неправильных глаголов своя форма для каждого прошедшего времени. Например:

Look — looked НО! Bring — brought — brought

Подробнее почитать о неправильных глаголах и скачать таблицу неправильных глаголов вы можете на нашем сайте.

Правило № 9

В английском языке существуют 4 типа вопросов:

We go to the theatre every Saturday. — Мы ходим в театр каждую субботу.

Правило № 10

Чтобы составить безличное предложение, понадобится местоимение It:

Правило № 11

После союзов as if, as though (как будто, будто, как если бы, словно) в условном наклонении, глагол to be в 3-ем лице единственного числа приобретает форму were:

Правило № 12

Условно-побудительные предложения в 1-м и 3-м лице образуются с помощью слова Let:

Правило № 13

Все знают, что слово many употребляется с исчисляемыми существительными, а слово much — с неисчисляемыми. Но, если вдруг, вы затрудняетесь, сомневаетесь, забыли правило или не понимаете, какое существительное перед вами, смело используйте сочетание слов a lot of. Оно подходит к обоим видам существительных.

Правило № 14

Множество английских слов — полисемичны, то есть могут иметь несколько значений. Это зависит от контекста и смысла предложения. Чтобы точнее понять перевод, следует обратиться к словарю и уточнить, в каком контексте употреблено слово.

Правило № 15

Глагол do может заменять основной глагол в предложении. Например:

Вот мы и добрались до пятнадцатого правила. Конечно, это далеко не все. Каждый раздел английского языка имеет свои особенности, а, значит, и свои законы. Мы рассказали вам только о самых основных. Надеемся, они вам пригодятся в изучении языка.

Рекомендую: Шпаргалку по английскому языку

Основы английского языка за 20 минут

» Грамматика » «There is a lot of people» vs «there are a lot of people»

Если вы сдавали экзамен на водительские права, то, возможно, помните забавный вопрос в одном из билетов: что делать, если к нерегулируемому перекрестку одновременно со всех сторон подъезжают 4 машины. Согласно правилам, каждый из них должен пропустить машину справа, но у каждого есть машина справа.

Правильный ответ на вопрос звучит как «правилами такая ситуация не предусмотрена». Вот и в английском языке тоже есть случай, в котором официальная грамматика разводит руками. Этот случай – выбор между there is a lot of [people] и there are a lot of [people]. На форумах и блогах идут войны о том, какой из вариантов правильный.

Давайте посмотрим на аргументы обеих сторон.

Перед тем, как продолжить, оговорюсь, что мы говорим именно об употреблении there is/are с a lot и с исчисляемыми существительными во множественном числе. В остальных случаях вопросов не возникает, например:

There is a lot of milk. Много молока (молоко неисчисляемое, поэтому is)

There are lots of people. Много людей (здесь lots of, поэтому are)

There are a lot of people

Аргумент этой стороны простой. A lot of people (a lot of cars, a lot of books) – это же много объектов. Поэтому и глагол должен быть, как для множественного числа – there are a lot of people.

There is a lot of people

«Минуточку», – говорит вторая половина ведущих спор. А вы разве не заметили артикль «a» перед «lot». Артикль «a» используется только с единственным числом, а «lot» — это «большое количество» — существительное как раз в единственном числе. Т.е. если у вас есть коробка с карандашами или мешок с картошкой – это по-прежнему одна коробка и один мешок, неважно сколько карандашей или картофелин находится внутри. Та же логика для a lot. Поэтому – there is a lot of people.

Примирения в этом споре никак не наступит – желающие отстаивать правильность своей позиции есть с обеих сторон. Официальная грамматика, как я уже говорил, в нерешительности – вроде как допустимы оба варианта.

А что же в реальной жизни?

Возьмем нашего любимого разрешителя всех споров – инструмент поиска частоты слов в google books – ngram. Это инструмент, разработанный гуглом, который позволяет сравнить популярность словосочетаний в огромной коллекции книг google.books.

Оказывается, there are a lot of people употребляется примерно в 15 раз чаще, чем there is a lot of people. Вот вам и ответ.

Похожие выражения

Похожая определенность возникает и с другими выражениями. Давайте сразу посмотрим на статистику:

there is/are a number of

there is/are a couple of

there is/are a group of

Похоже, что там где речь идет о том, что объектов много – а это как раз случаи с a lot of, a number of или a couple of – чаще используется форма множественного числа are.

А вот в случае же a group of – группа воспринимается, как что-то одно, неделимое. Поэтому и форма единственного числа is.

Итак, в споре there is/are a lot of people и у той и у другой стороны есть весомые аргументы. Грамматические справочники, стараются не влезать в этот спор. А в реальной жизни, как оказывается, форма there are a lot of people популярнее на порядок.

Сравнительные конструкции asas, not so as

И мало кто осознает, что положительная степень сравнения, то есть исходная форма прилагательного или наречия, также может применяться в сравнении.

Положительная степень используется в сравнительных конструкциях asas, not so as.

Грамматическая структура и значение конструкции asas

Данная структура соответствует русским формулировкам «такой же, как», «настолько, насколько» или просто сравнению при помощи союза «как». Таким образом, данная конструкция применяется для выражения равенства или неравенства двух объектов. Для сравнительной конструкции as as характерны следующие схемы использования:

| первый объект + глагол + as + прилагательное + as + второй объект | |

| His flat is as big as your flat. | Его квартира такая же большая, как твоя квартира. |

| This flat is as good as anyone can get for this price. | Эта квартира настолько хороша, насколько можно найти за такую цену. |

| первый объект + глагол + as + наречие + as + второй объект | |

| Tom doesn’t drive as well as he told us. | Том не водит так хорошо, как он нам рассказывал. |

| We came as quickly as we could. | Мы пришли так быстро, как только смогли. |

| первый объект + глагол + as + выражение количества + as + второй объект(в таком случае характерен перевод «столько, сколько» и т.п.) | |

| They don’t really have as many cars as they told you. | У них в действительности не так много машин, как они вам рассказывали. |

| There is as much money in this case as you promised me. | В этом кейсе столько денег, сколько ты мне обещал. |

Если с выражением равенства объектов все более или менее однозначно (кстати, конструкции, подтверждающие равенство, в речи встречаются не так уж и часто), то выражение неравенства стоит рассмотреть отдельно.

Грамматическая структура и значение конструкции not soas

Как видно из приведенной выше таблицы, конструкция asas встречается и в утвердительных и в отрицательных предложениях.

Однако существует еще одна структура, отвечающая за выражение неравенства, то есть сравнение с использованием положительной степени сравнения в отрицательных предложениях – not so as.

Эта конструкция означает «не такой, как», «не настолько, как» и употребляется только в отрицательных предложениях:

| George is not so tall as his sister Kate. | Джордж не такой высокий, как его сестра Кейт. |

| Tom is not so good at mathematics as I am. | Том не так хорош в математике, как я. |

Поскольку в современном английском языке благодаря глобализации его применения наблюдаются тенденции к упрощению, а конструкция as as может употребляться во всех типах предложений, включая отрицательные, то употребление структуры not so as наблюдается все реже.

Выражение неравенства: прилагательные

Показать, что два объекта не одинаковы по тому или иному качеству или свойству, можно, используя структуру not as + прилагательное + as или not so + прилагательное + as. При этом первый из сравниваемых объектов «в меньшей степени» проявляет ту или иную характеристику. Порядок следования сравниваемых объектов обратный, нежели при сравнении при помощи прилагательного в сравнительной степени + than. Сравним:

| not as + прилагательное + as / not so + прилагательное + as | прилагательное в сравнительной степени + than |

| This bag isn’t as heavy as that one. / Эта сумка не такая тяжелая, как та. | That bag is heavier than this one. / Та сумка тяжелее, чем эта. |

| Jennifer is not so tall as Jane. / Дженнифер не такая высокая, как Джейн. | Jane is taller than Jennifer. / Джейн выше, чем Дженнифер. |

It isn’t as old as

It’s not as old as

It is not so old as

Выражение неравенства: глагол + наречие

Для сравнения неравных действий может использоваться структура глагол +not + as + наречие + as или глагол + not + so + наречие + as. Порядок сравниваемых объектов (действий) здесь также будет обратным по сравнению с конструкцией наречие в сравнительной степени + than. Сравним:

| глагол +not + as + наречие + as / глагол + not + so + наречие + as | наречие в сравнительной степени + than |

| Tom doesn’t paint as well as we’d hoped. /Том не рисует так хорошо, как мы надеялись. | We’d hoped Tom would paint better than he does. /Мы надеялись, что Том рисует лучше, нежели в действительности. |

| Alice didn’t come so early today as she did yesterday. / Элис не пришла сегодня так рано, как вчера. | Yesterday Alice came earlier than she did today. / Вчера Элис пришла раньше, чем сегодня. |

Неравенство: выражение количества

| not + as + much/many + as или not + so + much/many + as | more + than |

| This gadget doesn’t have as many options as the other one. /Этот прибор не имеет так много опций, как другой. | The other gadget has more options than this one. / Другой прибор имеет больше опций, чем этот. |

| I don’t earn as much money as you do. / Я не зарабатываю так много денег, как ты. | You earn more money than me. / Ты зарабатываешь больше денег, чем я. |

such + словосочетание с существительным + as

Иногда вместо as/so применяется such (такой). Это происходит в том случае, если внутри «сравнительной рамки» оказывается словосочетание с существительным:

| Harry doesn’t have such an interesting job as Paul. | Гарри не имеет такой интересной работы, как Пол. |

| The excursion to the outdoor museum never takes such a big amount of time and money as the excursion to the art gallery does. | Экскурсия в музей под открытым небом никогда не требует такого большого объема времени и денег, как экскурсия в картинную галерею. |

Усиление и ослабление равенства/неравенства при помощи наречий nearly, quite, just, nowhere near

Когда мы хотим показать, что различия между сравниваемыми объектами значительные или, наоборот, совсем небольшие, то описываемые в данной статье сравнительные конструкции дополняются наречиями nearly — почти, вовсе; quite – совсем, практически; just – точно; nowhere near – ничуть, отнюдь, ни в коей мере.

| nearly | My town is nearly as old as Moscow.Great Britain isn’t nearly as big as Canada. | Мой город почти такой же старый, как Москва.Великобритания вовсе не такая большая, как Канада. |

| quite | My flat is quite as big as yours.Tom doesn’t play chess quite as well as George does. | Моя квартира практически такая же большая, как твоя.Том играет в шахматы не совсем так хорошо, как Джордж. |

| just | His bicycle is just as expensive as mine. | Его велосипед точно такой же дорогой, как мой. |

| nowhere near | My town is nowhere near as big as Moscow. | Мой город отнюдь не такой большой, как Москва. |

Автор- Александра Певцова

Каких случаях пишется lot of. Much и Many в английском языке

Hello, people! В этой статье мы подробно разберем правила употребления в английском языке слов «much», «many» и «a lot of», узнаем различия между ними, обсудим нюансы использования их в речи, а также покажем примеры для наглядности.

Перевод и транскрипция: much — много, очень, немало, значительно, весьма;

There is much black paint left in the garage.

В гараже осталось многочерной краски.

Также, обычно используется в отрицательных (negative) или вопросительных (interrogative) предложениях:

Chris does not have muchchange. Only a few five dollar bills.

У Криса нет много денег для размена. Только несколько пятидолларовых купюр.

В утвердительных предложениях «much» иногда задействуется, когда подразумевается более формальный и официальный стиль.

There is much concern about genetically modified food in the UK.

В Великобритании остро стоит вопросотносительно генно модифицированных продуктов питания.

Транскрипция и перевод: как и «much», «many» [«menɪ] переводится как «много»;

Употребление: используется исключительно с исчисляемыми существительными во множественном числе;

However, despite manyefforts many problems remain unsolved.

Тем не менее, несмотря на значительныеусилия, многие проблемы остаются нерешенными.

В отрицаниях и вопросах с исчисляемыми существительными «many» также встречается довольно часто:

How manyquail eggs are in this salad?

Сколько перепелиных яиц в этом салате?Anthony does not have many bottlesof winein his own private bar. At least that»s what he»s saying.

У Энтони немногобутылок вина в его собственном баре. По крайней мере, он так говорит.

Может употребляться в утвердительном предложении, когда нужен оттенок формальности.

There were manyscientific articles taken into account to make a decision.

Во внимание было принято много научных статей для вынесения решения.

A lot of

Транскрипция и перевод: по значению «a lot of» [ə lɔt ɔf] схоже с «much» и «many» и подразумевает тот же перевод — много;

Jack had a lot ofpeanutbutter left in the jar.

У Джека осталось многоарахисовойпасты в банке.

Эквивалентом «a lot of» является «lots of» (еще более неформальная форма).

Lots of teenagers learn Korean because they are into k-pop.

Многиеподростки изучают корейский, потому что увлекаются музыкальным жанром «k-pop».

| СЛОВО | Употребление | Значение |

| исчисляемые существительные(множественное число) / отрицание + вопрос / утверждение = формальный стиль | ||

| неисчисляемые существительные / отрицание + вопрос / утверждение = формальный стиль | ||

| больше / более | ||

| The most | неисчисляемые + исчисляемые существительные / прилагательные | большая часть / самый |

| A lot (of) | неисчисляемые + исчисляемые существительные / неформальный стиль | |

| Lots (of) | неисчисляемые + исчисляемые существительные / крайне неформальный стиль |

У всякого языка есть своя история, в которой можно проследить происхождение почти каждого слова. В электронном оксфордском словаре последнего издания можно узнать интересные факты об образовании большинства лексических единиц.

В английский язык much many, a lot of вошли разными путями. Они обозначают количество предметов, но, чтобы использовать их в предложениях, необходимо знать определенные правила.

Во-первых, вам следует знать, какие вещи считаются в английском исчисляемыми, а какие неисчисляемыми. Причем, многие слова можно перевести из разряда тех, которые нельзя сосчитать, в считаемые и наоборот.

Many и Much в английском языке

Слова many и much в английском языке означают «много», но несут различную смысловую нагрузку. Кроме того, в современном английском языке они по большей части употребляются в вопросительной или отрицательной форме.

Первое из этих слов употребляется с теми предметами, которые можно сосчитать:

Have Alan and Dick seen many squirrels in the park? Алан и Дик видели много белок в парке.

There are not many lizards in this forest. В этом лесу не много ящериц.

Чтобы употребить many и much в утверждении, перед ними необходимо поставить слова too, so, as:

Too many people came to watch the semi-final. Слишком много людей пришло посмотреть полуфинал.

У слова much другое предназначение. Оно указывает на большое количество неисчисляемого вещества.

Don’t use too much water taking a bath. Принимая ванну, не используй слишком много воды.

Was there much sand in the garden after that strong wind? Было ли много песка в саду после такого сильного ветра?

У правил практически всегда бывают исключения, и поэтому возможны такие предложения:

She has washed his cloths in so many waters. Она постирала его одежду во многих водах.

They crossed so many sands of different deserts last year. В этом году они пересекли много песков различных пустынь.

Кроме того, неисчисляемые предметы можно считать, поместив их в различные контейнеры, и употребить слово many:

Have you preserved many jars of jam for winter. Мы заготовили много банок варенья на зиму.

So many bars of chocolate melted on a very hot day. Много плиток шоколада растаяло в жаркий день.

Употребление a lot of английском языке и упрощает ситуацию, и в некотором роде делает ее немного сложнее. С одной стороны, эта конструкция употребляется и с неисчисляемыми существительными, и с предметами, которые можно сосчитать.

After the hiking trip, they drank a lot of water. После похода они выпили много воды.

A lot of apples were not rape. Многие яблоки были неспелыми.

С другой стороны, приходится задумываться, какую форму to be употребить перед этим словосочетанием в некоторых предложениях. Опять же приходится обращать внимание на исчисляемость или неисчисляемость предметов:

There is a lot of water in the pond. В пруду много воды.

There are a lot of pears in the tree. На дереве много груш.

Вопросы с How much и How many

Вопросы с how much часто употребляются в сочетании с конструкцией there is:

Разница между much и many

Much, many, few, a littleВсевозможные связанные с количеством слова в английском языке порой приводят к ужасающей путнице в голове, состоящей из вопросов когда, где, какое из них употреблять? Чтобы не усугублять проблему, стоит в качестве первого шага провести различение между хотя бы двумя из них – much и many, чтобы убедиться, что не всё так страшно.

Much и many – наречия, используемые для обозначения количества в значении «много». В разговорном языке встречаются преимущественно в вопросительных и отрицательных предложениях.

Сравнение

Сперва отметим общее: и то, и другое слово относятся к большим количествам чего-либо или кого-либо. Как только вы хотите сказать о нескольких предметах, о much и many стоит забыть. Масштабность – их удел. Если это сложно запомнить, можно воспользоваться простой аналогией: many и money созвучны, а money чаще ассоциируются с большими суммами (желаемыми или действительными). Ну а much просто идёт с many в компании.

Правда, стоит соблюдать осторожность с отрицательными предложениями, где not many и not much в русском переводе равносильны словам «мало», «немного»: I don’t have much time – У меня немного времени.

Теперь перейдём к различиям. Здесь тоже всё просто и более того – мы можем вновь воспользоваться созвучием. Несмотря на то, что «деньги счёт любят», в английском языке они относятся к неисчисляемым существительным, а с таковыми следует употреблять much.

С теми же существительными, которые относятся к исчисляемым, используйте many. Как запомнить? Ну хотя бы отметив для себя то, что словосочетание «many money» звучит не очень удобно в нашем языке.

И достроим логическую цепочку: неудобно, значит нужно much, значит much – с неисчисляемыми существительными.

Стоит помнить, что к последним относятся:

Выводы TheDifference.ru

Употребление much, many, few, little, a lot of, plenty

Чтобы не пропустить новые полезные материалы, подпишитесь на обновления сайта

Замечали ли вы, как часто мы используем в речи слова «много», «мало», «несколько» и как не любим называть точные цифры? Скрытные по своей природе англичане тоже очень часто употребляют в речи эти слова.

Когда мы говорим «много» по-английски, то используем слова many, much, a lot of, plenty of, а когда говорим «мало» – few, a few, little, a little. Эти слова называются determiners (определяющие слова), они указывают на неопределенное количество чего-либо.

Из статьи вы узнаете, когда и где нужно использовать much, many, few, little, a lot of, plenty of в английском языке.

Ключевую роль в выборе определяющего слова играет существительное. Именно от того, какое перед нами существительное, исчисляемое (countable noun) или неисчисляемое (uncountable noun), зависит, какой будет determiner. Еще раз напомним, что исчисляемые существительные мы можем посчитать и у них есть форма множественного числа (a boy – boys). А неисчисляемые существительные не имеют формы множественного числа (water – some water), и мы не можем их посчитать.

Мы разделили все слова на три группы в зависимости от того, с каким существительным они употребляются. Каждую группу мы рассмотрим в отдельности.

| Неисчисляемые существительные | Исчисляемые существительные | Исчисляемые и неисчисляемые существительные |

| How much money have you got? – Как много у тебя денег?There is little ink left in my pen. – В моей ручке осталось мало чернил. | I have many friends. – У меня много друзей.He has got few friends. – У него мало друзей. | There is a lot of sugar there. – Там много сахара.There are plenty of plants in the garden. – В саду много растений. |

Many, few, a few с исчисляемыми существительными

Слова many (много), few (мало), a few (несколько) используются с исчисляемыми существительными. Many обозначает большое количество чего-либо: many apples (много яблок), many friends (много друзей), many ideas (много идей).

Противоположность many – это few: few apples (мало яблок), few friends (мало друзей), few ideas (мало идей). У few часто негативное значение: чего-то очень мало, недостаточно, так мало, что практически нет.

A few имеет промежуточное значение между many и few, переводится как «несколько»: a few apples (несколько яблок), a few friends (несколько друзей), a few ideas (несколько идей).

– Do you have many friends in this part of the city? – У тебя много друзей в этой части города?

– No, I don’t. I have few friends in this part of the city. – Нет, у меня мало друзей в этой части города. (то есть недостаточно, хотелось бы больше)

– I have a few friends in the city centre. – У меня есть несколько друзей в центре города.

Much, little, a little с неисчисляемыми существительными

Слова much (много), little (мало), a little (немного) используются с неисчисляемыми существительными. Обычно к неисчисляемым относятся жидкости (water – вода, oil – масло), слишком маленькие предметы, которые невозможно посчитать (sand – песок, flour – мука), или абстрактные понятия, так как их нельзя увидеть или потрогать руками (knowledge – знание, work – работа).

Much обозначает большое количество чего-либо неисчисляемого: much sugar (много сахара), much milk (много молока), much time (много времени).

Противоположность much – это little: little sugar (мало сахара), little milk (мало молока), little time (мало времени). Little, как и few, означает, что чего-то недостаточно, очень мало.

A little подразумевает под собой небольшое количество чего-то, что нельзя посчитать: a little sugar (немного сахара), a little milk (немного молока), a little time (немного времени).

– Did she put much salt in the soup? – Она много соли положила в суп?

– No, she didn’t. She put little salt in the soup. – Нет, она положила мало соли в суп. (можно было больше)

– I added a little salt in her soup. – Я добавил немного соли в ее суп.

A lot of, plenty of – универсальные слова

Слова a lot of (много) и plenty of (много) самые «удобные»: мы можем использовать их как с исчисляемыми существительными, так и с неисчисляемыми.

A lot of (lots of) заменяет much и many: a lot of people (много людей), lots of tea (много чая). Plenty of обозначает, что чего-то очень много, то есть достаточно или даже больше, чем нужно: plenty of people (очень много людей), plenty of tea (очень много чая).

We bought lots of souvenirs and plenty of tea when we were on vacation in Sri Lanka. – Мы купили много сувениров и очень много чая, когда были в отпуске на Шри-Ланке.

Особенности и исключения

Есть ряд существительных, которые кажутся исчисляемыми, но на самом деле таковыми не являются. Иногда бывает сложно определить «исчисляемость» существительного.

Если вы не уверены, какое существительное перед вами, лучше уточните это в словаре.

Обратите внимание, что в английском языке к неисчисляемым относятся advice (совет), news (новость), work (работа), money (деньги), research (исследование), travel (путешествие), furniture (мебель).

They have much work to do. – У них много работы.

Как научиться употреблять прилагательные с исчисляемыми и неисчисляемыми существительными правильно

Употребление прилагательных с исчисляемыми и неисчисляемыми существительными в английском языке имеет свои хитрости. Какие же?

Существительные в английском бывают исчисляемые и неисчисляемые. Чаще всего они одинаково сочетаются с прилагательными. Но есть ситуации, когда нужно точно знать, какие прилагательные следует употреблять с исчисляемыми, а какие с неисчисляемыми существительными. Давайте же рассмотрим эти правила.

Общие правила употребления прилагательных с существительными

Неисчисляемые существительные обычно не имеют формы множественного числа. Например: sky, love, trust, butter, sugar. Именно поэтому в английском языке нельзя сказать: “He saw many beautiful skies.” (Он видел много прекрасных небес) или: “She bought two milks.” (Она купила два молока).

Употребление исчисляемых и неисчисляемых существительных с прилагательными в большинстве случаев является идентичным. Например:

Однако важно помнить, что со следующими прилагательными употребление исчисляемых и неисчисляемых существительных будет различным:

Some/any

Прилагательные some и any могут употребляться как с исчисляемыми, так и с неисчисляемыми существительными. Примеры:

Much/many

Прилагательное much употребляется только с неисчисляемыми существительными. Например:

С исчисляемыми существительными употребляется прилагательное many.

Little/few

Прилагательное little употребляется только с неисчисляемыми существительными. Например:

С исчисляемыми существительными употребляется прилагательное few.

A lot of/lots of

Выражения a lot of и lots of являются аналогами прилагательных much и many, но, в отличие от них, могут использоваться как с исчисляемыми, так и с неисчисляемыми существительными.

A little bit of

Прилагательное a little bit of в английском языке употребляется довольно редко и всегда сопутствует неисчисляемым существительным. Например:

Plenty of

Прилагательное plenty of может употребляться как с исчисляемыми, так и с неисчисляемыми существительными.

Enough

Аналогичным образом, enough может употребляться со всеми существительными.

Прилагательное no следует употреблять как с исчисляемыми, так и с неисчисляемыми существительными.

Much many a lot of, few little — количественные местоимения в английском языке (Quantifiers)

Как известно, показать число в английском языке можно не только с помощью числительных, но и посредством других частей речи, а именно количественных местоимений (much many a lot, etc.). Количественные местоимения в английском языке известны многим, так как употребляются в речи они довольно часто. Безусловно, имеют такие структуры и различия, которые считаются очень важными. Поэтому важно определить те условия, при которых используются такие pronouns, и обозначить ключевые отличия.

Основные характеристики количественных местоимений

Эти структуры английского языка неспроста получили название quantifiers, потому что они призваны показывать число объектов, пусть и неточное. Грамматика предусматривает использование этих структур как с единственным, так и с множественным числом. Следующая маленькая таблица покажет основные типы этих pronouns, которые употребляются с двумя числами:

Many much и a lot of (lots of)

Для правила much many a lot of одно из важных условий – это исчисляемость зависимых слов, с которыми они употребляются, т. е. те или иные структуры подходит исключительно для countable или uncountable nouns.

Так, например, определяя разницу между much or many, важно помнить, что первый вариант используется только с неисчисляемыми существительными, а второй – с исчисляемыми.

Соответственно, many и much показывают множественное число, вот только то, использовать much или many, определяет зависимое слово. Конструкция very much переводится как «очень сильно» и часто используется.

Кроме того, слова many/much довольно часто входя в структуру вопроса и вместе с наречием how образуют смысл «сколько? как много?». Вот как это выглядит:

· How many books have you read for the last year? – Сколько книг ты прочитал за прошлый год?

· How much water do you spend daily? – Not much – Сколько воды ты расходуешь ежедневно? – Не много

Помимо запоминания правил употребления much и many, важно уделить внимание и такой конструкции, как a lot of, а также практически идентичную ей lots of. Они почти ничем не отличаются, возможно, lots of используется в разговорной речи немного чаще, но на этом их отличия заканчиваются. Сама суть обеих конструкций – по-прежнему показывать смысл «много», но эта структура является универсальной и подходит как для countable, так и для uncountable nouns. Например:

· A lot of people gathered on the city streets and cried – Много людей собралось на улицах города и кричало

· Don’t buy a lot of butter, we don’t it very much – Не покупай много сливочного масла, мы не очень его любим

Пожалуй, единственный нюанс, касающийся употребления much many и a lot of, заключается в том, что последняя конструкция не может образовывать вопрос с how, а первые две могут.

Little / a little, few / a few

В отличие от much и many, little и few – это два слова, которые используются для отображения значения «мало». Ключевая разница между few и little также строится на понятии исчисляемости. Однако с little и few важную роль играют еще и артикли, от которых также зависят некоторые нюансы.

Так, используя слово little, говорящий имеет в виду «мало» с чем-то неисчисляемым: little water – мало воды, little gold – мало золота, и т. д. С countable nouns в значении «мало» употребляется только few: few pupils – мало учеников, few dogs – мало собак, etc. Фразы very little и very few также возможны.

Note: хоть слово few и пишется просто, у многих часто возникают проблемы с его произношением; его транскрипция будет выглядеть как [fjuː], а произношение будет созвучно со словами dew, Sue, etc.

Крайне важно отметить, что в языке также присутствую такие структуры, как a little и a few. Артикль в этих случаев решает довольно сильно: little переводится «мало», a little – «немного, но все же есть», т. е. в более положительном смысле; few переводится «мало», a few – «несколько». Кроме того, немногие знают и о такой структурах, как the little («то немногое, которое») и the few («те немногие, которые»). Вот несколько примеров:

· The few who remained on board the ship were ill – Те немногие, которые остались на борту корабля, были больны

· We have a few people to carry water. – Yes, but we have little water – У нас есть несколько человек, чтобы принести воду. – Да, но у нас мало воды

There is и there are

Известные многим с детства конструкции there is и there are также показывают число и употребляются в тех ситуациях, когда просто нужно показать, что где-то что-то есть, было или будет. Так, there is показывает единственное число и требует после себя только неопределенный артикль, а there are – множественное, и артикля обычно нет, если только речь не идет о конструкции a lot of (фраза there is a lot of также возможна, если речь идет о чем-либо неисчисляемом). Например:

· There are a lot of mice in the attic – На чердаке много мышей

· There is some soup in the bowl – В миске есть немного супа

· There are many vegetables in the yard, bring them – Во дворе есть много овощей, принеси их

Таким образом, количественные местоимения образуют развернутую категорию pronouns и имеют довольно много особенностей использования и образования. Все эти нюансы являются неотъемлемыми атрибутами английского языка и обязательно должны учитываться, иначе будет нарушен не только грамматический, но и лексический строй всей фразы.

garipx

Member

I am sure some people here will immediately say «hey, this topic should be opened in the English subforum, not here which is about «Etymology/History of languages».

But, this is a question that can not be answered, or can not be answered correctly by any person whose native language is English, either. They have not.

So, this is relevant to this part of forum, history/etymology of languages in general, of English in particular. You’ll see.

As for one who learnt English later, I was taught that, as a general rule, it is «how many» for countables and it is «how much» for uncountables.

For specific example, «money», they say «how much money» because money is «uncountable» (according to them).

Now, we have to talk about Language&Mathematics as there is this criteria, «countability». According to linguists(?), it seems that «money» is an «uncountable» thing as they say «how much money».

Lets also give examples, eg, dollar and cent not to be repeated here by posters who’ll reply in this thread.

They say «how many dollars» as «dollar» is countable. And, some say «how much cent» and some say «how many cent», there is no agreement in that, at least between people who I know of, mostly Americans. Even this uncertainty in «how many cent or how much cent» shows that there is a problem, in «countability» of money which is also seen in the language English.

Money is countable or uncountable, according to the linguists?

(etymology of «money» is also to be mentioned if necessary, and, I guess, necessary, to answer such a question.)

berndf

Moderator

garipx

Member

garipx

Member

Maybe, this topic needs a little stimulation as what exactly the question here may not be clear. Lets summarize first what are known.

There are two keywords here: Money and Countability.

I’m not a linguist, so, I checked on the net:

Etymology: Money (no need to give any reference as these were written everywhere on the net)

— The word «Money» originally from the Latin word moneta, meaning ‘mint’ or ‘currency’, which was later adapted as moneie in Old French.

— Moneta was originally a title given to the Goddess Juno, in whose temple money was minted in the earlier times, in Rome.

— and there is this on a forum (I don’t know if it is speculation or not): The word «Money» is derived from «Mann» in Tamil means Land (more preciously mud)

Maybe, there are other claims, but, I leave them to people here on this forum.

Countability: In the English, related to «Much» and «Many»: Ok, it seems that, in some languages like English, two different words are used depending on the countability while in some languages, for ex in Turkic, single word (çok) is used for the both, for countable and for uncountable quantities. This differentiation in this example into two words or integration into one word is probably due to the interaction between the languages and the mathematics, so, this is about history of language and mathematics. Since there are two different words (much and many) in English, English fits better than Turkic in questioning «money is countable or not» relating language&mathematics.

Combining these, etymology of money and countability in the language:

Option «Moneta», a given title to a Goddes, as origin of «Money» makes one thinks «money is countable» if Moneta is a person. If not, it is flue.

Option «Mann», mud in Tamil, as origin of «Money» makes one thinks «money is uncountable».

From history to today. (for centuries)

Current usages of «Money» in sentences, such as «cash flow, liquidity, etc», tell that «money is uncountable» and it is considered «liquid» like «water.» That must be why we see «how much money».

(For those who may have any objection to these and for those who may prefer to add somethings, I give a pause here to myself before stimulating further.)

Senior Member

If money is used as a countable noun, I would interpret it as referring to currencies. Like «Cambodia uses two different moneys at the same time». The usage doesn’t still sound quite idiomatic to me, but I believe, the grammar works. But then, I am no native English speaker. So.

In any case, the idea is that money (in its normal sense) is «counted» (rather «measured») in the units like dollar and lira, and not in discrete pieces or instances. Therefore it is uncountable. I think, it helps to compare it with some nouns which can be both countable and uncountable depending on the meaning, e.g. time. The time that is measured in minutes and days is uncountable (How much time have we got?). But then there is also the countable «time» (Turkish. defa/kere), e.g. How many times have you visited India, and how much time have you spent on each visit?

You need to be careful about a couple of things. Countability is a grammatical category, that exists in some languages (like English, but I believe also Turkish, please read on). And even when different languages share this apparently identical category, they may differ in exactly which nouns belong to which category. Like most grammatical categories, there is always some amount of randomness involved, e.g. in English, advice and information are uncountable (don’t ask me why!), but the corresponding words in Bengali (pɔramɔrso and tottho) are countable. As a learner, you just have to learn it!

Gavril

Senior Member

I’ve heard things like how much cents (plural) in colloquial speech, but not how much cent (though it’s possible that people have said it).

garipx

Member

Dib,

It is good you reminded «time» and «days, minutes, etc» as analogy to «money» and «dollar, etc», respectively. Our topic here will probably be more about such analogies. However, to focus on «money» and its «countability or not», yes, we also need to look also at other languages and I ask this. Is there any word in any language that means/implies «money» itself is countable?

Yes, in Turkish, we don’t say «kaç tane para? (how many money?)», but, we don’t also say «kaç tane lira? like it is normally said in English (how many dollar?)

Also, in Turkic, there is no opposite word (for uncountables like «much») to «tane» (piece) (used for countables like «many»). So, shortly, we use «kaç» for the both (how many and how much) and it is not clear «kaç» here is for countables or uncountables and answer to «kaç?» is again one word (çok) unlike English with two words (many and much) that seperate countability clearly unlike Turkic. This doesn’t mean that there is no countability in Turkic, but, «countability» in Turkic just isn’t as clear as in English in particularly to «money». So, I stay with English when questioning about «money» and its «countability or not». And, it seems that «uncountability of money» is a general rule in any and all languages including English. So, chosing English fit the purpose here, as it reflects general stiuation (uncountability of money) in all world languages and it has a clear specific word (much) seperated clearly from countables (many.)

Lets not go into other things such as «advice», «information», etc whether they are countables or not and in which languages they are countables and uncountables.

Since «money» (or para or whatever in any other language) is «uncountable» thing in all languages (unless claimed otherwise by an example) lets focus on «money» only as it is also one of most important things, maybe, the most, for everybody in the world.

So, to focus more on «money» and «countability», and to make it a fruitful discussion, is it ok to go with analogies hereafter? Expressions such as «money is like water flow», «money is like time flow», etc. are expressions that tell about «money» and its language history sufficiently? (if this, analogy making, is ok, we can go ahead without doubt?)

Gavril,

Thanks for clarification about «cent». I guess we will also come back to it again, later, once «money» is clarified more. (I have some doubt, money itself was actually maybe a countable thing. But, I can’t bring any evidence, at least for the moment, to prove it or to get rid of my doubt. So, this topic.)

Senior Member

«Money», as a magnitude, seems an uncountable concept to me (and this is how English speakers treat it). You cannot (or very rarely) count in magnitudes, you count in units. You don’t count in lengths, you count in meters, feet or whatever.

However, the name for the magnitude may indeed be derived from the unit, in this case from the word for «coin» or the currency in use at the time of the coinage (pun intended). For example, in Catalan, the word for «money» is a plurale tantum: diners. The origin of the word is a plural of diner «denary», an ancient currency that since became obsolete long ago is rarely used as a singular noun. But even so, at the time both meanings co-existed («denary» and «money» when pluralized) you cannot argue «money» was countable because what you could count was denaries, not money. If you said tres diners, people would understand «three denaries», never «three moneys», which in my opinion makes no sense, in any language.

What can be argued, is whether the primary form of the noun for a concept in a given language is countable or uncountable. «Advice» is uncountable in English because it refers to the general concept and not a single piece of it, and this is why it must resort to other methods to count «advice», just as you would resort to euros, dollars or whatever to count money. However, it is (mostly) countable in Romance languages because it indeed refers to a single piece of advice, and the reverse method to imply the general concept might be pluralizing it, for example.

So it’s not like the same exact concept might be countable or uncountable depending on the language. Just like «eyeglasses» is the same thing worldwide, but different languages have different strategies to mean the same concept, as well as that of a single eyeglass.

I don’t know where you got that from but I’m pretty sure it’s false.

garipx

Member

But, I am not sure if I understood your second paragraph well. On a coin collectors website, I learnt some coin currency names in ancient Romans time. For example, 1aureus=2quinarii=25denarii=50quinarii=100sestertii=200dupondii=etc. Here, the word «denarii» (plural of denarius) looks similar to the word in Catalan you mentioned «diners» (plural of denary), but, I understand «denarius» in the coin is like «cent» and «denarii» is like «cents», that’s «unit/s» of «money». So, plural tantum «diners» is somethings like that rather than «money»? Or, exactly, «diners=money». I mean, as a conclusion, my question to you to be sure is that «diners» in Catalan is countable or uncountable? If I did understand correctly, «diners too is uncountable», right? (this is important because if «diners» is «countable», or if there is such a word which breaks the rule «money is uncountable», then, the generalization «money (and its any corresponding word in any language in the world) is uncountable» will fail. If this generalization to all languages about «money» is true, then, we can continue as we will have found that «uncountability of money» is valid in all languages.)

Testing1234567

Senior Member

That you can count the amount of water in milliliters does not make water countable.

Similarly, that you can count the amount of money in dollars does not make money countable.

garipx

Member

Although «length» is already mentioned, ok, «volume» and «liters, etc» too can be added to the analogy list about «money» as some volumes may not have lineer (directly measurable) lengths (eg, a rain droplet, its volume is measured indirectly, by measuring mass and by calculation. Lets add also «mass» and, eg, «kg, etc» as another analogy to «money and dollar».) I guess these analogies/similarities are enough to understand what the money is, from point of view of countability, that also have interactions with languages.

Lets summarize analogies now.

I don’t know if it is a linguistic notation for analogy or not, but, there is a notation not widely known, used for analogy. It is «::»

Lets use it and this mathematical notation «< >» for set and «( )» for subset.

So, with the criteria «countability», here are some of our analogies:

Now, with this we have, normally, I should go to a forum where «physics», «economy» and «mathematics» are talked. But, I’ll stay here as we don’t need advance knowledge of physics, economy and mathematics and some elementary knowledge in these fields is sufficent and, main question here is related to what we really understand from «money», relevant to «language».

Ok, up to now, no any counter example (there is a word for «money» in ‘that’ language and it is «countable») has been given, all people here have said «money is uncountable» in all languages. Of course, we may not know all languages details as there are hundreds of languages in the world and not all people in the world is member of this forum. However, to be able to go ahead, following methodology, we need to make an «assumption», by extrapolation «what is known» (money is uncountable) in languages that we know to «what is unknown» (money is uncountable really?) in all languages we don’t know. Supposing this «assumption» (money is uncountable in all languages in the world) is valid, we can go ahead now.

Senior Member

Diner «denary», is a plain countable noun, you can say without any problem tres diners «three denaries». As you would do with any currency, just that this one is obsolete.

But diners «money», even if it derives from a countable noun using a typical method for countable nouns (pluralization), is uncountable. Just because, as a universal idea, you can’t count in a magnitude, you count in units.

I think your analogies are well-founded, they are based on this idea of magnitude-unit pairs.

However I think it is dangerous to say that the «countability» of some words is a universal intrinsic feature. Because the primary word for it may refer to either one single piece or the general concept, and by definition, they are countable and uncountable, respectively, depending on the language.

So we can safely say that «advice» is uncountable in English but countable in Romance languages. However, this is because they do not strictly refer to the same thing. The former refers to the general concept, and the latter to a single piece of it. That’s why, by definition, one is uncountable whereas the other one is countable.

This is just my five cents (pun intended again).

garipx

Member

Since you frequently warned me about «countability» that may differ from language to language depending on the word (advice, etc), lets fix a thing here first, to avoid bifurcation/branching toward an undesired chaos in our conversation here.

«Countability» here in this topic is narrowed to the countability in money, that is, to «mathematical countability», like counting numbers «1, 2, 3, and so on» that is how we count money by «discretizing» it into some units such as «dollar.»

So, here in this topic, the universality is not the universality (or not) of «countability. Since it is narrowed to money we can write this sentence comfortably, right?

. «uncountability of money is universal in all languages».

(unless stated otherwise, with a counter-example «word» in a language corresponding to «money».)

Diners in Catalan: So, from whatever it was evoluted, its final form «diners» is equivalent to «money», they both are uncountable. So, we can write analogy above (*) also for «diners as

Since we are using English here in our communication, lets use

Lets summarize all talks here in a single line, by rewriting analogy (*) here again, however, by chosing only one (the best one, most familiar to the common public) of subsets in the set at the right hand side of analogy (*). Result is:

where the words in capital letters are uncountable while the words in small letters are countables as they are units.

Lets use «cent» instead of «dollar» as the cent is the real unit value name of that money.

(no need to go into detail of «liter» such as «milliliter, nanoliter, etc» where «milli, nano, etc» are somethings else, irrelevant to the topic.)

So, final simplified version of our analogy is:

This shortened version of analogy conforms also with «mathematical economy» or «economy mathematics» as they use similar terms «liquidity, cash flow, etc.» in their calculations. And, all «money mathematics» is built on this philosophy (or reality?) that says «money is like liquid which is uncountable. Its unit, eg, cent is like liter of liquid which is countable.»

Now, we can talk about this analogy, that simplifies the topic, «money’s uncountability», universal in the languages.

(If there is no any nonagreement at all among all of us, I’ll try to stimulate/stir/blurr this «crystal clear» result. However, later, a cup of coffee time for me.)

Let me rewrite final simplified version of analogy here as last line in this post, as my attemps will be to «break» this analogy «::»

Senior Member

I think, I personally agree with your sets of analogy. I am also okay with building further on the assumption:

garipx

Member

Before attempting to «break» this commonly accepted analogy above which I simply write with notation «::», let me tell a little math first for those who may say «how in the world money appears like liquid in mathematics?»

Liquid/fluid/flow. These are «continuum» things and continuum is an uncountable thing according to the physics&mathematics unless it is discretized into pieces.

Mathematicans handling «money» in their calculations see money as a «continuum», such as liquid/fluid/flow, that’s why we hear «liquidity, cash flow, etc» from economists who are using terms of mathematicans&physicist actually.

Ok, garipx, give an example?

Since «countability» is mostly related to «mathematics of numbers», lets write here one simple equation so that you can see «most important numbers» in mathematics, used also in various fields from physics to engineering to economy, etc. in one simple equation. Some of you probably know it.

It is called Euler Identity (EI): e^(i.Pi) + 1 = 0.

where

«e»=2,71828. (three dots mean «etc»)

«i»=square root of «-1», so, imaginary number.

«Pi»=3,14159.

«1» and «0» = you already know.

I won’t go into details of this equation, what the hell this equation in reality is, etc. They are not on-topic here.

I wrote this here just to show «numbers» in one simple line, purposely.

Lets pick «e» here which is called «e»uler number, which is an «irrational number», that’s, numbers after comma never end, that’s, never repeat.

So, we can say this «e» is an uncountable number. And, this «e» is used also in calculations of continuous compound interest rate for your money in the bank account.

Why such a «strange» number «7489,2739340231. » appeared in hands of mathematicans here, specifically in this interest-rate example?

Because they use, for ex, «e» (2,71828. ) which is irrational, uncountable number in their money interest rate calculations. Uncountable contiuum such as Liquid/fluid/flow in mathematics appears in such numbers like «e».

So what? Using «e» in bank interest calculations is wrong? It’s another story we can talk later. Point of this post is «how uncountability of money appears in money mathematics». It appears, for ex, in use of number «e» which is uncountable number. We see this now. Money mathematics in detail is not our topic here, we can talk about it elsewhere, or some simple basic things here later.

So, isn’t it good as it fits analogy MONEY::LIQUID well? I can not use the word «certainly» when answering this.

What if this MONEY::LIQUID analogy is not a correct analogy? What happens? Money mathematics will totally fail then? No, but, there will be a «repairement» in «all money mathematics.» And, to do this, we need to be sure if there is any error to be repaired, and we cannot do anything without talking, so, «language», and it is what we are doing now. Having also said these in this post, now, lets question this analogy:

(Ps: Dib, I saw your post when I was writing my this post. Yes, I am aware (you probably are more aware than me as I am not a linguist) of that «sample» info here in this thread is probably insufficient to make such a generalization «uncountability of money is universal in all languages». My assumption here is based on what you posters here said and on the silence not opposing this generalization. So, if we all here and scientists (mathematicans, etc) agree in that assumption, it is not my assumption only. If there is an error or not in this assumption, «uncountability of money is universal», what we will be doing here in this thread is this, questioning, using analogy, as it is done by sciences also about money. Ok, to keep our talks shorter and in a methodology, step by step, lets write this analogy again as last line of this post:

garipx

Member

(you can go to the bottom, to the last paragraph directly, if you don’t have time to read this long post.)

if we chose, for ex, this analogy

could it be better?

Maybe, but, then, our coversation would have been more conceptual or more philosophical in money-time analogy.

In case of money-liquid analogy, this is quasi-conceptual, less philosophical as liquid has a physical form and money too has a physical form.

Their main common character of money and liquid is their uncountability and this is our main reason for making analogy between them and it is sufficient to chose liquid for our need. Their existing physical forms also keep us in reality more than that we can do with analogy money-time.

So, it is «sufficient best» to take «liquid», among available things, as an analogy to «money» for our purpose here that’s to question «money’s uncountability.»

Now, lets write it here again to focus and question this analogy:

Here, «cent» and «liter» are to be discussed later as they are obviously «countables».

Since we are to learn about «money» here that we «suppose» we don’t know, then, we should look at its analogy, i.e. «liquid».

Solid and liquid/fluid are considered as «contiuum» in classical physics and their math calculations are done accordingly, while gas is considered as «particles» and its math calculations are done accordingly.

So, lets eliminate «gas» as «money» in math calculations is «not» handled like «particles», otherwise, «money» would have been considered as «countable».

Solid does not fit, either, as it doesn’t «flow».

So, we confirm «liquid/fluid», also due to its visible «flowability» character which «money» too has, another commonly accepted property of «money».

These (solid, liquid, gas) forms are forms that have been studied much by many scholars in the history and today. So, we know a lot about these.

I’ll write here another «new» material form which has been academically much less studied than those (solid, liquid, gas) and a few years ago, one of few researcher studying that «new» form of material had called it «4th form of material» after 3 forms of materials (solid, liquid, gas).

What is that «new» material form? Don’t be surprised.

How comes!? This is not new. Well, that’s why I used » » when I was writing «new». (a little irony, but, still new, as it is new to the science community actually.)

How new?

Question to any person: Wheat/grain is solid? or liquid? or gas-like particle?

Depending on what you are studying, it is solid, and also liquid, and also gas.

You can see these forms in «wheat/grain» with your insight view, and, even eye-visually.

But, since we chosed «liquid/fluid» as analogy to «money», you can ask «how in the world wheat/grain can be correlated to the liquid!?».

Have you ever seen a combine harvester «pouring» wheat in harvesting or wheat «moving» in an open channel at flour milling factory? Wheat just acts like a liquid, with an engineering approximation, it can also be called «flow» and fluid flow formulas can be used also for «wheat flow» at an engineering approximation level. («approximation» is another keyword here in «money», we may talk about it later.)

Ok, here, not many people may know these matematical formulations of flows, his words of «garipx» may not be enough. It is not necessary to know mathematics of flows, even visually, you can see wheat flow in a channel as «liquid flow», «solid flow» like mud flow in a truck trailer on which wheat flows slowly, and «gas/particle flow» when a handful of wheat is thrown into the air.

SO, BEST ANALOGY for «MONEY» is «WHEAT/GRAIN». better than «liquid» analogy.

When wheat is handled as a solid, it is «uncountable», it is counted only by its volume/mass/weight (in cubicmeter or kg, lb, etc.)

BUT, because of this way of counting wheat by «kg, etc» in «trade», its countability of wheat/grain as particle «piece» is usually forgotten especially by «scholars» in general and by «mathematicans» in particular in sciences of related fields, again, because of their minds on economy/commerce/trade when they see «money». This countability by «piece» DOES exist also in the countability of «real money», eg, «coin».

SO, here is my claim: instead of this analogy,

(Also, it’ll make more sense as «cent» too has a particle physical form, as «coin».)

Here you are. (waiting for your attacks, to the claim here.)

Senior Member

My main question to you is: «What does all this have to do with Etymology, History of languages, and Linguistics», please? I hope you are getting to that aspect soon.

I guess, you really mean the following:

If the digits of the decimal (or any other rational-base) representation of e are put together in an ordered set (say, X), it will be uncountable.

However, that assertion would be wrong. X will be countably infinite. You can very easily define a one-to-one mapping between the elements of X and the set of all natural numbers, e.g. by using the position of the element in X. That is the classic definition of a countably infinite set.

Anyways, I would like to wait to find out what language-related issue this discussion brings up ultimately.

garipx

Member

(I’ll answer your main question «what all these have to do with this EHL forum?» after a few words about «mathematics» you quoted/mentioned.)

I am not a mathematican either though I had used some theoretical pure mathematics in my research studies, about chaos, more than two decades ago.

People, especially pure theoretical mathematicans, say mathematics is «exact» science. Maybe true, maybe not.

But, when it comes to «money» I call their pure theoretical mathematics as «over-engineered» mathematics. What I mean by this is that:

Lets forget «e» (2,71828..etc), instead, lets take another similar number that is related to the term you used «countably infinite».

0,999999999999999999999. (to infinity) = 1.

There is such a claim, whether you call it hypothesis or theorem or law. To me, it is «unprovable» equality as there is «infinity» in this logic of equality.

How can we talk about «countability» of this number «0,9999999999999. «? (forget about its potential equivalency to 1. Money is not infinite.)

If this number «0,999999999. » is considered countable, we need to find «99999999999. » (without comma between numbers) by multiplying «10000000. » so that we can reach at a «unit» that is a necessity to call it a countable. So, since we can never make comma disappear in «0,9999999999. «, therefore, I call it «uncountable» number. Same happens for «e», «pi», etc.

On the other hand, for example, we can do this eliminating comma for number «325,76». Like we do in «$325,76», when we multiply by «100», «comma» between numbers «325,76» disappears, and, «$325,76» becomes «32576 cents». This is countable, one by one, as «1,2,3,etc» till we reach «32576».

We can NOT do same operation for «irrational numbers» such as «e» in that numbers after comma never ends, assumption, ends at the infinity, a blurry term.

Ok, but, we use number «infinity» in mathematics? Yes, but, it is not a number actually, just a symbol, an indefinite symbol and all practical calculations using «infinity» are «cut» after a certain order of magnitue level and it is called «approximation.» What is done in money calculations, even if «e» or «infinity» is used in calculations, at the end, cutting two digits after comma, that’s a «centum» level «appromixation.»

Anyway, lets not go further about theoretical mathematics. Fixing this reality is enough, «money is not infinite» which is another thing about «money» that tells us potential countability of money. (with analogy «money::wheat», no more potential, countability of money is real.)

All these mind confusions occuring in money calculations is due to the analogy of «money» to «liquid», handling money as if it is liquid. which is wrong, my claim here.

So, what has these with this EHL forum? We are discussing «un/countability of money» here. I claimed now «money is countable thing» by making a new analogy of «money» to «wheat» unlike standard commonly accepted analogy of «money» to «liquid» which is uncountable.

So, according to analogy «money::liquid», it is «how much money» while according to (new) analogy «money::wheat» it is «how many money».

So, according to this new claim, «how much money» is a historical error in the language (probably by scholars of old old days) to be repaired to «how many money.». IF my this claim is false, then, prove that «money is uncountable» is true. How can you do that without using mathematics&language? Shall I just simply accept how it has been said throughout the history and today? I question. till «1cent». When it is said to you «do you have «1cent?», yes, it is a language, but, what do you understand from this? If you «really» have «1cent» in your pocket, you answer it «yes, I have «1cent». But, when you don’t have «1cent», but, when you have «$1», do you still answer «I have 100cent?». Such an answer, linguistically too, will be illogical. Because you are saying «I have 100cents, but, I don’t have 1cent.». an illogical saying in a language and this has been said by all in the world and in all time.

berndf

Moderator

There is nothing to be proven. Countability is a property of a concrete concept expressed by a concrete word in a concrete language. In English, money exists as a countable and as a non-countable word. Money in non-countable in sentences like

(1) He had a lot of money.

(2) There was no money on his account.

It is countable in sentences like

(3) The monies raised during the campaign have all been transferred to our CS account.

(4) He kept his fortune in different monies.

The linguistic concept of countability has nothing to do divisibility and has nothing to do with the concept of countability in set theory. A word or, more precisely, a concept X is countable if meaning is attached to the expressions 1X, 2Xs, 3Xs, etc. If money means a quantity of money (as in 1 & 2) then it in non-countable because no natural unit of measurement is attached to the concept. If money means transaction amount (as in 3) or type/kind of money (as in 4) then meaning is attached to expressions one money, two monies etc.

The basic principle of what constitutes a countable and what constitutes a non-countable word is fairly universal. But which concrete words are countable and which are non-countable is language specific. E.g. information is always non-countable in English while the French word information is in most cases countable (with the meaning piece of information).

garipx

Member

When a person just learning English reads your examples (1, 2, 3, 4) may ask «if these told are true or not» (here, «truth» is understood mostly opposite of «lie» in languages, particularly in «spoken languages» and that person would go to the English lesson forum to learn if those (1, 2, 3, 4) are «really» said so or not.

Similarly, he would go to the English forum to learn how people whose native language is English say for «money», «much money» or «many money».

Such things are «information gathering» in «already available» things, but, unknown to a new learner.

So, this «uncountability of money is universal» requires a proof, a proof even in only English. That should be done like a mathematican does to prove «2+2=4» which is well known. Saying that «countability in mathematics and in linguistics is different» does not make sense, at least in this topic in which the thing we are talking is «money» which is considered same thing for the both, for the mathematican and for the linguist, for all others as well.

What are the language and the mathematics? (related to countability). With simple examples.

1tulip + 1rose = 2flowers. Here, what takes my attention is «tulip and rose», their odor/smell/beauty/etc rather than their quantities/mathematics.

1tulip + 1tulip = 2tulips. Here, what takes my attention is numbers/figures as all units/names (tulip) are same.

1money + 1money = 2money/s. Here, my eyes are opened wider because it is about «money» and people immediately «jump» to the total «2moneys» as it is bigger number (economy motivation).

,