How much people live in moscow

How much people live in moscow

Moscow

Position of Moscow in Europe

District

Subdivision

Central Federal District

Federal City

Contents

Moscow is world-renowned for its architecture and its performing arts. It is well-known for the elegant onion domes of Saint Basil’s Cathedral, as well as the Cathedral of Christ the Savior and the Seven Sisters. The Patriarch of Moscow, whose residence is the Danilov Monastery, serves as the head of the Russian Orthodox Church. Moscow also remains a major economic center and is home to a large number of billionaires. It is home to many scientific and educational institutions, as well as numerous sports facilities. It possesses a complex transport system that includes the world’s busiest metro system, which is famous for its architecture. Moscow also hosted the 1980 Summer Olympics.

History

Early history

The oldest evidence of humans in the area where Moscow now stands dates from the Stone Age (Schukinskaya Neolithic site on the Moscow River). Within the modern bounds of the city, a burial ground of the Fatyanovskaya culture has been discovered, as well as evidence of early-Iron Age settlements of the Dyakovskaya culture, on the grounds of Kremlin, Sparrow Hills, Setun River, and Kuntsevskiy forest park.

At the end of the first millennium C.E., the territory of Moscow and the Moscow Oblast was inhabited by the Slavic tribes of Vyatichi and Krivichi. By the end of the eleventh century, Moscow was a small town with a feudal center and trade suburb situated at the mouth of the Neglinnaya River.

The first written reference to “Moscow” dates from 1147, when it was an obscure town in a small province inhabited mostly by Merya, speakers of a now extinct Finnic language. Yuri Dolgoruki called upon the prince of the Novgorod Republic to «come to me, brother, to Moscow.» [1] In 1156, Prince (Knjaz) Yury Dolgoruky of Kiev ordered the construction of a moat and a wooden wall, which had to be rebuilt multiple times, to surround the emerging city. [2] After the sacking of 1237-1238, when the Mongol Khanate of the Golden Horde burned the city to the ground and killed its inhabitants, Moscow recovered and became the capital of an independent principality in 1327. [3] Its favorable position on the headwaters of the Volga River contributed to steady expansion. Moscow developed into a stable and prosperous principality which attracted a large number of refugees from across Russia.

Center of power

Under Ivan I the city replaced Tver as capital of Vladimir-Suzdal and became the sole collector of taxes for the Mongol-Tatar rulers. By paying a large amount of tribute, Ivan won an important concession from the Khan. Unlike other principalities, Moscow was not divided among his sons but was passed intact to his eldest. In 1380, prince Dmitri Donskoi of Moscow led a united Russian army to an important victory over the Tatars in the Battle of Kulikovo. Although this victory is regarded as historically important, it was not decisive. After two years of battle, Moscow was completely destroyed by khan Tokhtamysh. In 1480, Ivan III had finally broken the Russians free from Tatar control, allowing Moscow to become the center of power in Russia. [4] Ivan III relocated the Russian capital to Moscow (previous capitals were Kiev and Vladimir), and the city became the capital of an empire that would eventually encompass all of present-day Russia and other lands.

The seventeenth century was rich in popular risings, such as the liberation of Moscow from the Polish-Lithuanian invaders (1612), the Salt Riot (1648), the Copper Riot (1662), and the Moscow Uprising of 1682. The city ceased to be Russia’s capital in 1712, after the founding of Saint Petersburg by Peter the Great on the Baltic coast in 1703.

Defeat of Napoleon

Capital of the Soviet Union

In January 1905, the institution of the City Governor, or Mayor, was officially introduced in Moscow, and Alexander Adrianov became Moscow’s first official mayor. Following the success of the Russian Revolution of 1917, on March 12, 1918, Moscow became the capital of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, later the Soviet Union. [5]

During the Great Patriotic War (the part of World War II after German invasion in the USSR) in 1941, the Soviet State Committee of Defense and the General Staff of the Red Army was located in Moscow. In 1941, 16 divisions of the national volunteers (more than 160,000 people), 25 battalions (18,500 soldiers) and four engineering regiments were formed among the Muscovites. In November 1941, German Army Group Center was stopped at the outskirts of the city and then driven off in the course of the Battle of Moscow. Many factories were evacuated, together with much of the government, and from October 20 the city was declared to be under siege. Its remaining inhabitants built and manned antitank defenses, while the city was bombarded from the air. It is of some note that Stalin refused to leave the city, meaning the general staff and the council of people’s commissars remained in the city as well. Despite the siege and the bombings, the construction of Moscow’s metro system, which began in the early 1930s, continued through the war and by the end of the war several new metro lines were opened. On May 1, 1944 a medal For the defense of Moscow and in 1947 another medal In memory of the 800th anniversary of Moscow were instituted. On May 8, 1965 in commemoration of the twentieth anniversary of the victory in World War II, Moscow was one of 12 Soviet cities awarded the title of Hero City. In 1980, it hosted the Summer Olympic Games.

In 1991 Moscow was the scene of a coup attempt by the government members opposed to the reforms of Mikhail Gorbachev. When the USSR was dissolved in the same year, Moscow continued to be the capital of Russia. Since then, the emergence of a market economy in Moscow has produced an explosion of Western-style retailing, services, architecture, and lifestyles.

Growth of Moscow

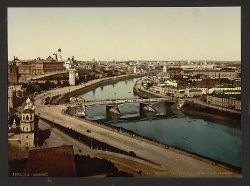

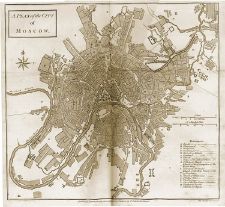

As with most medieval settlements, early Moscow required fortresses to defend it from invaders such as the Mongols. In 1156, the city’s first fortress was built (its foundations were rediscovered in 1960). A trading settlement, or posad, grew up to the east of the Kremlin, in the area known as Zaradye (Зарядье). In the time of Ivan III, the Red Square, originally named the Hollow Field (Полое поле) appeared. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the three circular defenses were built: Kitay-gorod (Китай-город), the White City (Белый город) and the Earthen City (Земляной город). However, in 1547, two fires destroyed much of the town, and in 1571 the Crimean Tatars captured Moscow, burning everything except the Kremlin. The annals record that only 30,000 of 200,000 inhabitants survived. The Crimean Tatars attacked again in 1591, but this time were held back by new defense walls, built between 1584 and 1591 by a craftsman named Fyodor Kon’. In 1592, an outer earth rampart with 50 towers was erected around the city, including an area on the right bank of the Moscow River. As an outermost line of defense, a chain of strongly fortified monasteries was established beyond the ramparts to the south and east, principally the Novodevichy Convent and Donskoy, Danilov, Simonov, Novospasskiy, and Andronikov monasteries, most of which now house museums.

By 1700, the building of cobbled roads had begun. In November of 1730, the permanent street light was introduced, and by 1867 many streets had a gaslight. In 1883, near the Prechistinskiye Gates, arc lamps were installed. In 1741 Moscow was surrounded by a barricade 25 miles long, the Kamer-Kollezhskiy barrier, with sixteen gates at which customs tolls were collected. Its line is traced today by a number of streets called val (“ramparts”). Between 1781 – 1804 the Mytischinskiy water-pipe (the first in Russia) was built. In 1813 a Commission for the Construction of the City of Moscow was established. It launched a great program of rebuilding, including a partial replanning of the city-center. Among many buildings constructed or reconstructed at this time were the Grand Kremlin Palace and the Kremlin Armoury, the Moscow University, the Moscow Manege (Riding School), and the Bolshoi Theatre. In 1903 the Moskvoretskaya water-supply had appeared.

The postwar years saw a serious housing crisis, which stimulated the invention of commieblocks; apartments were built and partly furnished in the factory before being raised and stacked into tall columns. There are about 13,000 of these standardized, prefabricated apartment blocks. The popular Soviet-era comic film Irony of Fate parodies this soulless construction method. A groom on his way home from his bachelor party passes out at an airport and wakes up in Leningrad, mistakenly sent there by his friend. He gets a taxi to his address, which also exists in Leningrad, and uses his key to open the door. All the furniture and possessions are so standardized that he doesn’t realize that this isn’t his home, until the real owner returns. The film struck such a chord with Russians, watching on their standard TVs in their standard apartments, that the film is now shown every New Year’s Eve.

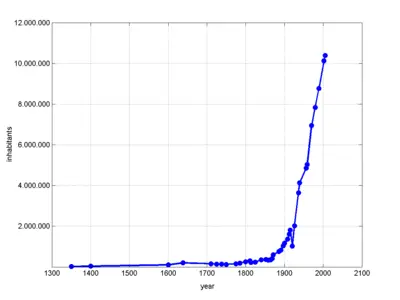

Population

The population of Moscow is rapidly increasing. The ubiquitous presence of legal and illegal permanent and temporary migrants, plus merging suburbs, raises the total population to about 13.5 million people. According to the 2010 Russian Census the population of the city proper was 11,689,048; however, this figure only takes into account legal residents, and not the several million estimated illegal immigrants and gastarbeiters living in the city. Moscow is home to an estimated 1.5 million Muslims, including about 100,000 Chechens, and between 50,000 and 150,000 Chinese.

Substantial numbers of internal migrants mean that Moscow’s population is increasing, whereas the population of many other Russian cities is in decline. Migrants are attracted by Moscow’s strong economy which contrasts sharply with the stagnation in many other parts of Russia. In order to help regulate population growth, Moscow has an internal passport system that prohibits non-residents from staying in the capital for more than 90 days without registration.

|

|

|

Government

Moscow is the seat of power for the Russian Federation. At the center of the city, in Central Administrative Okrug, is the Moscow Kremlin, which houses the home of the President of Russia as well as many of the facilities for the national government. This includes numerous military headquarters and the headquarters of the Moscow Military District. Moscow, like with any national capital, also hosts all the foreign embassies and diplomats representing a multitude of nations in Russia. Along with Saint Petersburg, Moscow is designated as one of only two federal cities within Russia. Moscow is located within the central economic region, one of twelve regions within Russia with similar economic goals.

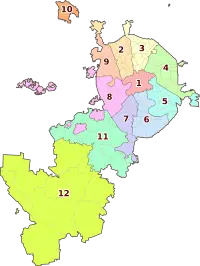

The entire city of Moscow is headed by one mayor. It is divided into 12 administrative okrugs and 123 districts. A part of Moscow Oblast’s territory was merged into Moscow on July 1, 2012; as a result, Moscow is no longer fully surrounded by Moscow Oblast and now also has a border with Kaluga Oblast.

All administrative okrugs and districts have their own coats of arms, flags, and elected head officials. Additionally, most districts have their own cable television, computer network, and official newspaper.

In addition to the districts, there are Territorial Units with Special Status, or territories. These usually include areas with small or no permanent populations, such as the case with the All-Russia Exhibition Center, the Botanical Garden, large parks, and industrial zones. In recent years, some territories have been merged with different districts. There are no regions of specific ethnicity in Moscow. And although districts are not designated by income, as with most cities, those areas that are closer to the city center, metro stations or green zones are considered more prestigious.

Moscow is the administrative center of Moscow Oblast, but as a federal city, it is administratively separate from the oblast.

Climate

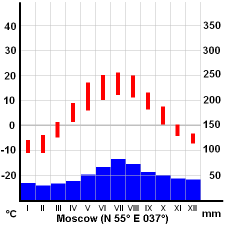

Monthly rainfall totals vary minimally throughout the year, although the precipitation levels tend to be higher during the summer than during the winter. Due to the significant variation in temperature between the winter and summer months as well as the limited fluctuation in precipitation levels during the summer, Moscow is considered to be within a continental climate zone.

City layout

Moscow is situated on the banks of the Moskva River, which flows for just over five hundred kilometers through western Russia, in the center of the East-European plain. There are 49 bridges across Moskva River and its canals within city limits.

Moscow’s road system is centered roughly around the heart of the city, the Moscow Kremlin. From there, the roads in general radiate out to intersect with a sequence of circular roads or «rings» focused at the Kremlin. [7]

The first and innermost major ring, Bulvarnoye Koltso (Boulevard Ring), was built at the former location of the sixteenth century city wall around what used to be called Bely Gorod (White Town). The Bulvarnoye Koltso is technically not a ring; it does not form a complete circle, but instead a horseshoe-like arc that goes from the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour to the Yauza River. In addition, the Boulevard Ring changes street names numerous times throughout its journey across the city.

The second primary ring, located outside the Boulevard Ring, is the Sadovoye Koltso (Garden Ring). Like the Boulevard Ring, the Garden Ring follows the path of a sixteenth-century wall that used to encompass part of the city. The third ring, the Third Transport Ring, was completed in 2003 as a high-speed freeway. The Fourth Transport Ring, another freeway, is currently under construction to further reduce traffic congestion. The outermost ring within Moscow is the Moscow Automobile Ring Road (often called the MKAD from the Russian Московская Кольцевая Автомобильная Дорога), which forms the approximate boundary of the city.

Outside the city, some of the roads encompassing the city continue to follow this circular pattern seen inside city limits.

Architecture

For a long time the skyline of Moscow was dominated by numerous Orthodox churches. The look of the city changed drastically during Soviet times, mostly due to Joseph Stalin, who oversaw a large-scale effort to modernize the city. He introduced broad avenues and roadways, some of them over ten lanes wide, but he also destroyed a great number of historically significant architectural works. The Sukharev Tower, as well as numerous mansions and stores lining the major streets, and various works of religious architecture, such as the Kazan Cathedral and the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour, were all destroyed during Stalin’s rule. During the 1990s, however, both the latter were rebuilt.

Architect Vladimir Shukhov was responsible for building several of Moscow’s landmarks during early Soviet Russia. The Shukhov Tower, just one of many hyperboloid towers designed by Shukhov, was built between 1919 and 1922 as a transmission tower for a Russian broadcasting company. Shukhov also left a lasting legacy to the Constructivist architecture of early Soviet Russia. He designed spacious elongated shop galleries, most notably the Upper Trade Rows (GUM) on Red Square, bridged with innovative metal-and-glass vaults.

Stalin, however, is also credited with building the The Seven Sisters, comprising seven, cathedral-like structures. A defining feature of Moscow’s skyline, their imposing form was allegedly inspired by the Manhattan Municipal Building in New York City, and their style—with intricate exteriors and a large central spire—has been described as Stalinist Gothic architecture. All seven towers can be seen from most elevations in the city; they are among the tallest constructions in central Moscow apart from the Ostankino Tower, which, when it was completed in 1967, was the tallest free-standing land structure in the world and today remains the tallest in Europe. [8]

The Soviet policy of providing mandatory housing for every citizen and his or her family, and the rapid growth of the Muscovite population in Soviet times, also led to the construction of large, monotonous housing blocks, which can often be differentiated by age, sturdiness of construction, or ‘style’ according to the neighborhood and the materials used. Most of these date from the post-Stalin era and the styles are often named after the leader then in power: Brezhnev, Khrushchev, etc. They are usually ill-maintained. The Stalinist-era constructions, mostly in the central city, are massive and usually ornamented with Socialist realism motifs that imitate classical themes. However, small churches, almost always Eastern Orthodox, that provide glimpses of the city’s past, still dot various parts of the city. The Old Arbat, a popular tourist street that was once the heart of a bohemian area, preserves most of its buildings from prior to the twentieth century. Many buildings found off the main streets of the inner city (behind the Stalinist facades of Tverskaya Street, for example) are also examples of the bourgeois decadence of Tsarist Russia. Ostankino, Kuskovo, Uzkoye and other large estates just outside Moscow originally belonged to nobles from the Tsarist era, and some convents and monasteries, both inside and outside the city, are open to Muscovites and tourists.

Attempts are being made to restore many of the city’s best-kept examples of pre-Soviet architecture. These revamped structures are easily spotted by their bright new colors and spotless facades. There are a few examples of notable, early Soviet avant-garde work too, such as the house of the architect Konstantin Melnikov in the Arbat area. Later examples of interesting Soviet architecture are usually marked by their impressive size and the semi-Modernist styles employed, such as with the Novy Arbat project, familiarly known as «false teeth of Moscow» and notorious for its wide-scale disruption of a historic area in the heart of downtown Moscow.

As in London, but on a broader scale, plaques on house exteriors inform passers-by that a well-known personality once lived there. Frequently the plaques are dedicated to Soviet celebrities not well-known outside of Russia. There are also many ‘house-museums’ of famous Russian writers, composers, and artists in the city, including Mikhail Lermontov, Anton Chekhov, Dostoevsky, Tolstoy and Pushkin.

Quick facts about Moscow

This section of the Moscow Hotels website provides information on geographic coordinates, area, population, government, climate, time, attractions, holidays, and so on.

Geographic coordinates

Moscow is located at 55 45 N and 37 37 E of the Greenwich meridian in the middle of the East European Plain. The area lies at a height of 30-35 meters above the Moskva river and about 150 meters above sea level

Total area

Moscow occupies more than 1,000 square kilometers. The boundary of the city corresponds to the Moscow Ring Road, which is situated at 15-17 kilometers from the city center. The city extends for 42 kilometers from the North to the South and for 35 kilometers from the East to the West.

Population

Government

Moscow as a separate subject of the Russian Federation is governed by a mayor, who is popularly elected for a four-year term, and by a 35-member Duma (assembly), which is the city’s legislature. Moscow consists of 10 administrative regions, which are subdivided into 128 districts. The Duma is elected from administrative regions and each district elects local councils. As the capital of Russia, Moscow is the seat of the national government. The Kremlin palaces house the majority of offices. The prime minister’s offices occupy the House of Government of the Russian Federation, usually known as the White House.

Area code

Moscow Standard Time — MST differs from Greenwich Mean Time — GMT

Summer MST = GMT+4 hours

Climate

The climate in Moscow is temperate continental. It is mainly characterized by hot summers and very cold winters. The amplitude in annual temperature range is 28 C. The cold period starts in October and ends in April. Snow falls in November and stays till March. The height of the snow cover usually reaches 350 millimeters. There may be long frosts or periods of thaw. The mild weather comes in June and stays till September. Rainfall levels during July and August average 72-78 millimeters per day.

Foundation

The date of Moscow’s founding is generally accepted to be April 4, 1147, when the first record of Moscow in Russian chronicles was done. Moscow’s history starts from a wooden fortress, which was built by order of Prince Yuri Dolgoruky on a hill at the confluence of the Moskva and the Neglinnaya rivers. It is often said that Moscow is the third Rome, because the main part of the city, according to the legend, was built on seven hills. The city’s general scheme can be represented as the system of concentric circles radiating from the Kremlin, Moscow’s geographical, historical and political centre.

Symbol

The official symbol of Moscow is a dark-red shield, where an ancient Old-Russian subject is depicted: St. George fighting down the Serpent. This symbol was restored in 1993 per sample of the first official symbol of Moscow, which was established in 1781.

International relations

Moscow has attitudes based on contracts and friendly communications with 50 cities and regions all over the world, 10 CIS countries, 7 Asian countries. There are 31 trade missions, 12 representations of the international organizations with labor relations, 137 diplomatic representatives (embassies) with accreditations in Moscow. Moscow carries out trading communications with about 200 countries. On a constant basis the Government of Moscow keeps in touch with sales representatives of more than 50 countries. More than 2,500 foreign companies are registered in capital representations, more than 7,5 thousand enterprises deal with the foreign capital. About 100 international exhibitions and fairs take place in Moscow every year.

Major attractions

Moscow boasts of its numerous attractions: Kremlin, Red Square, Tretyakov Gallery, Bolshoi Theater, Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, Armory, Novodevichy Convent, St. Basil Cathedral, Arbat, The Church of Christ the Savior, Poklonnaya Mountain, Archangelskoye Estate, Ostankino Estate and others.

Holidays

New Year (January 1st), Orthodox Christmas (January 7th), «Defenders of the Motherland Day» (February 23rd), «International Women’s Day» (March 8th), «International Labor Day» (May 1st and 2nd), «Victory Day» (May 9th). «Russian Day» (June 12th), «Day of Reconciliation and Accord» or the anniversary of the October Revolution (November 7th)

The Moscow Hotels Russia provides travelers with the most useful and up-to-date information on the best hotels of Moscow. With the help of our website you can easily reserve a room in any hotel of Moscow through our online reservation system. In addition to hotel reservations, we offer a full range of travel services. We serve both corporate and leisure clients and strive to satisfy every customer.

Moscow

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

Read a brief summary of this topic

Moscow, Russian Moskva, city, capital of Russia, located in the far western part of the country. Since it was first mentioned in the chronicles of 1147, Moscow has played a vital role in Russian history. It became the capital of Muscovy (the Grand Principality of Moscow) in the late 13th century; hence, the people of Moscow are known as Muscovites. Today Moscow is not only the political centre of Russia but also the country’s most populous city and its industrial, cultural, scientific, and educational capital. For more than 600 years Moscow also has been the spiritual centre of the Russian Orthodox Church.

The capital of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (U.S.S.R.) until the union dissolved in 1991, Moscow attracted world attention as a centre of communist power; indeed, the name of the seat of the former Soviet government and the successor Russian government, the Kremlin (Russian: Kreml), was a synonym for Soviet authority. The dissolution of the U.S.S.R. brought tremendous economic and political change, along with a significant concentration of Russia’s wealth, into Moscow. Area 414 square miles (1,035 square km). Pop. (2010) city, 11,738,547; (2020 est.) city, 12,678,079.

Character of the city

If St. Petersburg is Russia’s “window on Europe,” Moscow is Russia’s heart. It is an upbeat, vibrant, and sometimes wearisome city. Much of Moscow was reconstructed after it was occupied by the French under Napoleon I in 1812 and almost entirely destroyed by fire. Moscow has not stopped being refurbished and modernized and continues to experience rapid social change. Russia’s Soviet past collides with its capitalist present everywhere in the country, but nowhere is this contrast more visible than in Moscow. Vladimir Ilich Lenin’s Mausoleum remains intact, as do many dreary five-story apartment buildings from the era of Nikita Khrushchev’s rule (the mid-1950s to the mid-1960s), yet glitzy automobiles and Western-style supermarkets, casinos, and nightclubs are equally visible. Many Orthodox churches, as well as some synagogues and mosques, have been restored, Moscow’s novel theatres have reclaimed leadership in the dramatic arts, and traditional markets have been revived and expanded. These markets, which under the Soviets were known as kolkhoz (collective-farm) markets and sold mainly crafts and produce, are now more sophisticated retail establishments.

A 3-Hour Commute: A close look at Moscow the Megapolis

How many people actually live in Moscow, and where does it stand compared with Seoul, New York, and Shanghai?

THE EIGHT AGGLOMERATIONS

The 2017 study «Agglomeration: World> Russia> Moscow”, conducted for the Moscow Urban Forum, was the first time in which the boundaries of Moscow’s urban sprawl and entire agglomeration were determined using international standards, which has allowed the Russian capital to be compared with other major competitors, and made it possible to answer the question of how many people are really living in Moscow. In addition, the study selected seven other metropolises: Tokyo, Seoul, Shanghai, Beijing, New York, Buenos Aires, and London. These cities are comparable in size, being among the world’s largest cities, but each demonstrates extremely different approaches to management.

WHO IS MISSED BY THE MOSCOW STATS

For Moscow, the official figures are as follows: as of 2017, the total population was recorded as 12,380,664. In 1991, by the way, there were just over nine million people. But as any Muscovite will tell you, the city is much bigger and the official statistics do not reflect the city’s constant changes. Estimates of the population inside the city limits range from 10 to 15 million, while the metropolitan area could be 15 to 25 million. Such miscalculations make it impossible to prepare accurate strategic and financial documents for the distribution of budgetary funds.

Counting the millions of workers commuting into Moscow every morning is the first big difficulty. The second is to determine the number of inhabitants based on residency permits or a census that is not related to the day-to-day functioning of the city. Without the standard methods of evaluation adopted in different countries of the world, international comparison of metropolises is impossible. However, the methods for determining the boundaries of a metropolis are unique in many countries. In Russia, it is common to mark the boundaries of a city using concentric circles surrounding the centermost point of the city. In contrast, urban centers in France generally have a medium-sized city with dependent rural areas, which are distinguishable by their administrations.

Different methods for defining boundaries. Metropolitan Territory

Different methods for defining boundaries.

Different methods for defining boundaries.

Different methods for defining boundaries.

Different methods for defining boundaries.

Different methods for defining boundaries.

Standard statistics are not helpful in determining the boundaries of the core and periphery. Big data analysis can help solve this problem. This study used filtered data gathered by the three largest mobile operators in the region. Relying on this data, it was possible to create maps of the urban agglomeration and calculate the population of the municipalities connected to it for the first time. The results revealed an accurate outline of the areas in which a large portion of the population commuted to work in Moscow, and could be analyzed to see the total number of jobs in each part of the metropolitan area, as well as the metropolis’s real population.

With this analysis of Moscow’s metropolitan area, the population slightly exceeds 20 million people. And its borders extend from the Moscow region to include the border areas of Smolensk, Tver, Yaroslavl, Vladimir, Tula, and Kaluga. In addition, the metropolis has 12 sub-nuclei with significant spans of 30-60 kilometers that surround Moscow.

Moscow’s metropolitan area spans over 26,000 square kilometers and has a population of over 20 million people

These sub-nuclei are cities that both attract workers from the surrounding areas and, at the same time, provide a commuting workforce to the Russian capital. The metropolitan area is almost 26,000 square kilometers, a size 10 times as large as the city’s administrative boundaries, which were were recently expanded and coined “New Moscow” in 2011, and almost 30 times the area of the city within the Moscow Ring Road that encircles the traditional city limits. Residents of the outlying areas are prepared to spend three hours traveling to the city center for work every day en masse. The scale and shape of Moscow’s metropolis are first and foremost dependent on the branches of the railway system, which are used daily by hundreds of thousands of people as the primary means of travel for those in the periphery.

The boundaries of the Moscow metropolitan area according to OECD methodology

The New York agglomeration

The Moscow agglomeration

The Beijing agglomeration

The Seoul agglomeration

The Tokyo agglomeration

The Shanghai agglomeration

THE FOUR RINGS

The third belt – the inner periphery of the metropolis that surrounds Moscow’s A107 highway (also known as the Small Ring Road) – is almost entirely developed. The area transitions back and forth between gated neighborhoods, summer homes, and large residential complexes, which results in quite a low average population density. Finally, the fourth belt of the megacity is characterized by wilderness sporadically dotted with developments. Besides these developments, the 12 additional sub-nuclei stand out among the fourth ring’s forests. For large metropolises in other countries, it is characteristic to have the population more evenly distributed across the territory.

Population density map. Moscow

Population density map. New York

Population density map. London

Population density map. Tokyo

Population density map. Shanghai

Population density map. Seoul

Population density map. Buenos Aires

Population density map. Pekin

LIFE IN THE CENTER

Each night, the center of Moscow empties out and comes alive again at sunrise. During the day, more than 40 percent of residents go to work inside the Third Ring Road. An area of slightly less than 100 square kilometers is occupied daily by several million people. The ability to concentrate resources in just one place makes the urban economy more efficient. All these effects are developed in the metropolis to an even greater extent. However, uncontrolled growth is also fraught with major risks. In Moscow, the situation with the distribution of jobs negatively affects the quality of life of all citizens. The outskirts and periphery of the city suffer from a lack of work, which forces people to spend time and resources on the road to the office.

Map of jobs. Shanghai

Map of jobs. Moscow

Map of jobs. Seoul

Map of jobs. Buenos Aires

Map of jobs. Tokyo

The best areas for both the residents and the city are those in which the residential and work functions are combined: mixed-use areas. On the agglomeration map of Moscow, they are marked by shades of yellow. Basically, these are the areas that are located where a canceled Fourth Ring Road would have been: Sokol, Akademicheckiy, and Basmanny. The quality of the environment and the optimal rhythm of life in them allows the residents to get to know each other better and promotes the formation of active local communities. Any changes in these parts of the city should occur in close dialog with the local population.

Map of the ratio of the density of jobs and housing. Beijing

Map of the ratio of the density of jobs and housing. Tokyo

Map of the ratio of the density of jobs and housing. Buenos Aires

Map of the ratio of the density of jobs and housing. Seoul

Map of the ratio of the density of jobs and housing. New York

Map of the ratio of the density of jobs and housing. London

Map of the ratio of the density of jobs and housing. Moscow

Most urban agglomerations face the problem of an excessive concentration of jobs. In such a situation, a balanced policy of urban and regional growth, at the intersection of economic and spatial planning, comes to the rescue. Some Asian agglomerations have been particularly successful in implementing such a strategy. In the metropolitan area of Seoul, over thirty years of constant planning made it possible to form several hubs equivalent to the city’s main nuclei and thereby relieve the center of the city. The Shanghai agglomeration is developing according to the 1-9-6-6 program: 1 agglomeration, 9 large satellite cities, 60 new cities, 600 main rural settlements. This development scheme is prescribed under the current master plan of the Shanghai metropolitan area, which covers 6,000 square kilometers.

The remarkable size of some megacities forces them to spend large amounts of money on planning work. Tokyo’s metropolitan area is the largest in the world, with a population exceeding 37 million people. It is also an example of a truly polycentric urban structure, whose existence is based on a nearly perfect planning system. To achieve this, up to 70,000 urban planners are involved in planning the Tokyo metropolitan area, one of the results of which is the creation of a highly-developed public transport system, linking together all areas of the city.

37 million people live in the metropolitan area of Tokyo, and its area of 10,369 square kilometers is 2.5 times less than that of the Moscow metropolitan area

Many agglomerations cope with their problems by utilizing a cluster policy, that is, by creating business cores that pertain to a specific professional orientation. The main advantage of business clusters for a city is the achievement of optimal labor productivity in them: they provide for the the possibility of centralized management of spatial and economic development. So, Seoul created five large world-class nuclei, specializing in marine logistics, finance, tourism, and polymer chemistry. In Shanghai, clusters are supported by the formation of Special Economic Zones (SEZs). These zones are mainly located on the periphery of the agglomeration, and their constituent companies specialize in specific export segments.

THE EAGERNESS OF FOOLISHNESS

Any correct decisions made in a timely fashion in the sphere of urban development can fail if the transport system does not keep up with the expansion of the city. Transportation in the metropolitan area has a trans-border character to it. Transportation, like in cities that do not take notice of administrative boundaries, must link the territories effectively, and spaces are divided by the invisible barriers of the zones over which many different municipalities and regions have responsibility. For this reason, transportation planning usually becomes the first step in inter-municipal coordination, but investing in it carries the highest price tag.

In London, the Crossrail system is currently being built, which should bring together the eastern and western agglomeration areas, pass under the city center, and in the future, perhaps, connect the northern and southeastern suburbs. The cost of this construction exceeds 15 billion pounds ($19.4 billion). In Seoul, funds from private companies have led to the construction of much-needed new branches of their metro. In return, those companies receive subsidies for the constructed facilities. Moscow managed to implement a large-scale reconstruction and launch of the MCC (The Moscow Central Circle metroline) by attracting more than 100 billion rubles ($1.7 billion) of private investment for the right to further reconstruct empty industrial zones near its new stations. The city also began the construction of the Great Metro Ring as well as new radial branches, and began to transform the system of overground routes. In this respect, the Russian capital can well be considered a model case for the successful transformation of transport infrastructure.

Transport networks of agglomerations

Transport networks of agglomerations

Transport networks of agglomerations

Transport networks of agglomerations

SEVEN WEALTHY MEGAPOLISES VS LONDON

Without a certain level of budget self-sufficiency, no city can influence the development of its own agglomeration: investments in infrastructure, culture, education, and transport are required. Adequate budget support is an important aspect of agglomeration management policies. Almost all large agglomerations have low-deficit budgets. That is, the funds collected from local taxes are usually enough to conduct an independent policy, choose priority areas for development, and finance major infrastructure projects. In this respect, out of all the chosen agglomerations, the situation is different only in London. Here, the city contributes only 37 percent of its own funds to the budget, forcing the mayor’s office to negotiate co-financing every year with the national government. This is due to the specificity of the British tax system, which probably creates unnecessary stress on the development of London.

In managed agglomerations, the citizens are 7% richer than in those that are unmanaged

Moscow is a city of federal significance and is its own region in the Russian Federation. For this reason, its budget self-sufficiency is incomparable with that of other Russian cities (which frequently suffer due to the existing system of tax distribution). The inability to plan freely for the future because of small budgets prevents the adequate transformation of Russian million-population cities into centers for the development of technology, culture, education and tourism.

However, the most difficult and arguably the most fundamental issue in the research is the management and coordinated development of agglomerations. The fact is that a city cannot influence what is happening outside its borders. For example, after coordinating the schedule of intercity bus and urban transportation throughout the various parts of the metropolitan area, it was possible to use just one travel card. On the other hand, the taxation of companies and residents is important for cities. If a person lives in a small city and works in a neighboring large city, he pays taxes where he works, and spends a large part of his salary there. The city of residence does not collect budgetary revenues, but it still must provide its citizen with high-quality services.

Nearby cities often have a common infrastructure: energy, water, and transport. Often the reluctance to invest in the common infrastructure of one of the neighbors turns into an accident that affects everyone. Such effects are known as spillover effects or «overflow effects». Another fact is that the townspeople in managed agglomerations are 7% richer than in those that are not managed. So, in the long term, this promises a multi-billion dollar gain. But not everything is so simple.

In Asia, the agglomeration strategy is formed at the national level. Seoul and the surrounding areas comprise half of the population and economy of South Korea. The government of the country controls the process of growth of the capital, for which a national law was passed to restructure the mega-region. In China, not only is the development plan for Shanghai coordinated at the national level, but, for example, so is even the mega-region of the Yangtze Delta, which is home to around 100 million. On the other hand, in New York, the master plan of agglomeration has been developed for over 100 years by the non-governmental organization RPA (Regional Plan Association). And the agglomeration itself — the business capital of the world — consists of a city and parts of three states and is in no way governed by the national government. In London until recently, there was neither a mayor nor a city council — they had been abolished by the government of Margaret Thatcher. In fact, until the year 2000, the London agglomeration was an accumulation of independent regions that had the right to agree among themselves on joint activities.

Today, the Coordination Council for Transport Development is operating between Moscow and the region. In comparison with other world agglomerations, Moscow is in an unusual position: the national government does not directly interfere with its growth, nor does it form guidelines and specific goals that would influence urban policy.

There is no single effective plan for managing agglomerations. In different situations, diametrically opposite approaches are best applied. In other words, what is good for Tokyo (tens of thousands of planners) can be a disaster for New York, which has been developing for over 100 years in the absence of a state planning body.

Agglomeration processes provide unique opportunities for development and growth, but also create risks that if ignored could lead to unfortunate consequences. And although all agglomerations are unique, each having specific management models, it seems the main problems they face are often similar.

6 RECOMMENDATIONS FOR THE MOSCOW AGGLOMERATION

— The city center should regain its residential functions.

— New urban centers with a focus on mixed-functionality areas need to be created.

— Moscow’s suburban areas should gradually draw jobs away from the center, as it is possible to adopt a strategy for creating clean, modern industrial enterprises.

— A strategy for the development of the districts and cities entering the near periphery needs to be developed.

— The formation of a network of full-fledged second-order nuclei located at a significant distance from the city, and the transformation of their industrial potential.

— The formation in the second-order nuclei of a new level of logistics infrastructure.

The formation of a large urban agglomeration can create new impulses for the growth of regional and national economies and improve the quality of life for millions of people. After thirty years of work in Seoul, several centers have been formed that have improved the structure of the city. The desire to cooperate gave Shanghai the opportunity to develop a network of specialized settlements throughout the metropolitan area and make the city one of the most progressive in the world. The efforts of tens of thousands of planners allow Tokyo to remain the largest and probably the most effective polycentric city formation in the world.

“Things have started to improve”: Moscow residents share thoughts on the city’s changes

From cycling infrastructure to public spaces, how do Moscow’s residents feel about the city’s urban renewal projects? Here they share their stories.

The ‘Moscow experiment’ has seen the city undergo renewal efforts over the last five years to improve liveability. But what do Moscow’s residents really think about the changes? We asked you to share your stories of life in the Russian capital, and reflect on whether Moscow is changing for better or worse.

The city centre may be seeing improvements in infrastructure and public space, but what about the suburbs? How involved have local citizens been in the changes? And what does the future hold for Moscow? We’ve rounded up a selection of your GuardianWitness contributions, comments and emails, which reveal the everyday experiences of Moscow’s transformations:

Change in attitude changes people

As a born-and-raised Muscovite, I can say that this experiment succeded halfly, only because it has not finished yet. And it is not only about change in infrastructure which made Moscow a better place, it also brought a new generation of young people interested in the better future. For example from my own experience, I find more and more of my friends interested in programming and urban planning due to their visits to lectures provided by Gorky Park and Strelka. At the same time we see a rise in creativity in terms of services, such as “анти-кафе” ( anti-cafes) where you pay for time spent there rather than for coffee, hipster barbershops which are also popular among general population, affordable lunch places and so on. One of the most popular cafes “Циферблат” even opened one more cafe, not in Moscow but in Manchester, and it shows that there is a big change of service business, which became more oriented at people, rather than just their money.

About pedestrians and automobilists

Moscow has undergone massive change in the last five years, but the most obvious developments concern parks, streets, and general navigation in the capital. Most of the developments are surely positive: the city has seemed to get more air. There have appeared more walking paths, pedestrian zones have been expanded, some streets have been closed for traffic altogether, parks are being renovated, and new bicycle lanes are being offered now to city residents and its guests.

However, there are negative changes as well, which have largely affected car owners: extension of the paid parking areas, and the increase of the average price, the need to navigate a bypass route in order to drive round pedestrian zones. But this coin has another side too: fewer cars in the centre means less exhaust fumes and cleaner air.

Muscovites look forward to the old parks being renovated, and the new ones being opened. New plans make excited everyone: new metro stations, new roads, new bicycle lanes and pedestrian footpaths.

It’s changing for better

Moscow is definitely changing for better now. As I see it, the authorities are trying to make a city a better place to live in, especially in remote residential neighborhoods, which is very good. Many parks were renovated, cycle lanes appeared. Moscow has become a nice place for long walks and cycling. The city has a lot to offer now including museums, and different events like exhibitons, summer outside activities and others.

It’s a pity that it takes so long but taking into account the size of the city and its population I can say the situation has changed even if compared to what it was like 4-6 years ago.

Better, definitely

I was born in Moscow, emigrated to the UK ten years ago, and have been coming back at least once a year ever since. Although it’s hard to tell from only a short visit, I can definitely see improvement in the capital: public transport operates better, local government services are better organised, the streets are cleaner. in my old neighbourhood (a very working-class, high-immigrant community), there are more ’high-street’ shops appearing, less potholes on the roads, new playgrounds, new trees being planted and even the occasional fountain being built. These things may seem little and shallow, but I can certainly see improvement in this sense, at least.

Moscow — is a big village. Moscow — is a big playground

“Live not survive” — the main task of urban planners today.

Some of the most notable changes are: The renovation of parks, which is now not so bad for a walk, especially in the evening. Playgrounds became the favorite place of kids, not homeless people and alcoholics. Also, fitness trainers and horizontal bars right on the street, enhanced pedestrian road in the center, bicycle parking system. Moreover, greatly improved the situation on the roads, that can please many motorists, which sit half of life in a traffic jams, and, of course, wi-fi in underground, this innovation was the most pleasurable one.

Moscow has long ceased to have a certain aesthetic. It shuffled so many different epochs and ideologies, that with such a level of disharmony and diversity can be compared only Berlin. Living in a city like this becomes normal to see the temple of the 18th century standing near panel building of Khrushchev era. However, our current mayor with all forces, is trying to find harmony in the this chaos. Is this Sisyphean task or not, only future will tell.