How rare is selective mutism

How rare is selective mutism

What Is Selective Mutism?

Aron Janssen, MD is board certified in child, adolescent, and adult psychiatry and is the vice chair of child and adolescent psychiatry Northwestern University.

Brand X Pictures / Johner Images / Getty Images

What Is Selective Mutism?

Selective mutism (SM) is a childhood anxiety disorder characterized by an inability to speak or communicate in certain settings. The condition is usually first diagnosed in childhood. Children who are selectively mute fail to speak in specific social situations, such as at school or in the community.

It is estimated that less than 1% of children have selective mutism. The first described cases date back to 1877 when German physician Adolph Kussmaul labeled children who did not speak as having «aphasia voluntaria.»

Selective mutism can have a number of consequences, particularly if it goes untreated. It may lead to academic problems, low self-esteem, social isolation, and social anxiety.

Symptoms

If you believe that your child may be struggling with selective mutism, look for the following symptoms:

While these behaviors are self-protective, other children and adults may often perceive them as deliberate and defiant.

Diagnosis

Although selective mutism is believed to have its roots in anxiety, it was not classified as an anxiety disorder until the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) published in 2013.

The use of the term «selective» was adopted in 1994, prior to which the disorder was known as «elective mutism.» The change was made to emphasize that children with selective mutism are not choosing to be silent, but rather are too afraid to speak.

The primary criterion for a diagnosis of selective mutism is a consistent failure to speak in specific social situations in which there is an expectation of speaking (e.g., school), despite speaking in other situations.

In addition to this primary symptom, children must also display the following:

Children who stop talking temporarily after immigrating to a foreign country or experiencing a traumatic event would not be diagnosed with selective mutism.

Causes

Because the condition tends to be quite rare, risk factors for the condition are not fully understood. It was once believed that selective mutism was the result of childhood abuse, trauma, or upheaval.

Research now suggests that the disorder is related to extreme social anxiety and that genetic predisposition is likely. Like all mental disorders, it is unlikely that there is one single cause.

Kids who develop the condition:

Other potential causes include temperament and the environment. Children who are behaviorally inhibited or who have language difficulties may be more prone to developing the condition. Parents who have social anxiety and model inhibited behaviors may also play a role.

Selective mutism also often co-occurs with other disorders including:

Treatment

Selective mutism is most receptive to treatment when it is caught early. If your child has been silent at school for two months or longer, it is important that treatment begin promptly.

When selective mutism is not caught early, there is a risk that your child will become used to not speaking, and as a result, being silent will become a way of life and more difficult to change.

Treatment for selective mutism may include psychotherapy, medication, or a combination of the two.

Psychotherapy

A common treatment for selective mutism is the use of behavior management programs. Such programs involve techniques like desensitization and positive reinforcement, applied both at home and at school under the supervision of a psychologist.

Medication

Medication may also be appropriate, particularly in severe or chronic cases, or when other methods have not resulted in improvement. The choice of whether to use medication should be made in consultation with a doctor who has experience prescribing anxiety medication for children.

Coping

In addition to seeking appropriate professional treatment, there are things that you can do to help your child manage their condition.

In general, there is a good prognosis for selective mutism. Unless there is another problem contributing to the condition, children generally function well in other areas and do not need to be placed in special education classes.

Although it is possible for this disorder to continue through to adulthood, it is rare and more likely that social anxiety disorder would develop.

Kotrba A. Selective Mutism: A Guide for Therapists, Educators, and Parents. Eau Claire, WI: PESI Publishing and Media; 2015.

Hua A, Major N. Selective mutism. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2016;28(1):114‐120. doi:10.1097/MOP.0000000000000300

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA). Selective mutism.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

Selective Mutism: Symptoms, Causes, Treatment, and Tips for Parents

What is Selective Mutism?

Selective Mutism (SM) is an anxiety disorder in which children do not speak in school, extracurricular or community activities, sports, etc., despite speaking at home or in other settings. Children with SM have the ability to speak and are often described by immediate family members as вЂchatty’ or вЂtalkative’ when observed at home and in other select environments. Despite speaking freely at home, children with SM appear to вЂfreeze’ and remain mostly or completely silent in social situations depending on the person, place, and situation or activity. Even subtle changes around them or shifts outside of their comfort zone can lead to drastic changes in (non)speaking. A child with SM may talk loudly and enthusiastically to a parent at home, in the grocery store aisle, and at a restaurant, but may immediately become, and remain, silent when a neighbor visits the home, an adult or peer walks in the same grocery aisle, or a waiter approaches the table to take an order. As known and deeply felt by families who are coping with SM, this pattern of reluctance in speaking greatly impacts the child’s fundamental ability to convey their needs and to engage fully at school, with friends, during afterschool activities, and in their neighborhood and community.

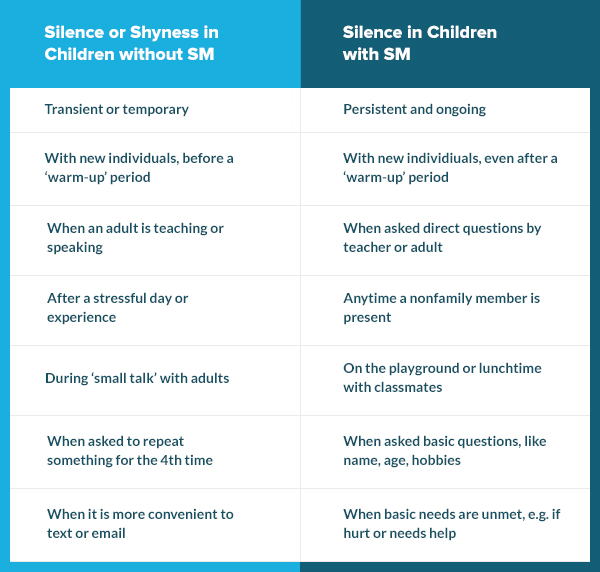

It can be healthy and adaptive for children to experience a range of speaking behaviors and to be more reserved around new children and adults, particularly when away from their caregivers. Even the most social and outgoing children can have moments of silence or speaking reluctance without a lasting impact on daily functioning. Of note, developmentally appropriate silence is transient and temporary and these individuals do speak when there is an expectation to speak (e.g., when called on in class or asked by a friend if they want to play). Therefore, we further distinguish children with SM from those without SM as those who have a consistent refusal to speak in specific social situations in which there is an expectation for speaking (e.g., at school), despite speaking in other situations (e.g., at home with family members), and the silence or reluctance to speak has a negative impact on the child’s daily life.

Take Our Quiz: Is it Shyness or Selective Mutism?

Does your child seem to “freeze up” in certain circumstances and not be able to or not want to speak? Answer a few questions to find out more.

Parents, caregivers, teachers, and mental health or medical providers unfamiliar with SM may misperceive social silence as вЂshyness’ or a temporary phase that the child вЂwill outgrow.’ As a general guideline, shyness represents an initial experience of reticence that is most likely to occur in new or unfamiliar settings or before an adequate вЂwarm-up’ period. A вЂshy’ child without SM may appear quiet during the first half of a friend’s birthday party when unfamiliar peers are present, within the first few weeks of a new school year, or when asked by a teacher to present to a small group or whole class without any notice or time to prepare. By comparison, a child with SM may continue to remain silent despite extensive warm-up periods, including after multiple playdates with a classmate, years in school with the same peers, or when asked by a friendly peer or adult about their name, age, or favorite interests. SM often impacts a child’s ability to get help, request to use the restroom, or tell others if they are hurt, lost, or in pain. See the table below for side-by-side comparisons.

Naturally, adults or children may also mistake selective silence in children with SM as вЂrudeness’ or deliberate attempts to defy others. It is important to recognize that children with SM suffer from anxiety and their silence is most often вЂrooted’ in worry associated with social evaluation or judgment, fear of making social mistakes, and uncertainty about one’s ability to be liked and accepted. Since the difficulties with verbal communication are consistent for individuals with SM, over time they can be labeled as the вЂone who does not speak.’ Further, children with this condition who are not appropriately identified and treated are at risk for the development of social anxiety disorder and other mental health disorders, as well as continuing to suffer from SM as adolescents and adults. This trajectory often leaves individuals and families feeling stuck in a pattern of social silence that greatly influences social, emotional, academic, and occupational health.

Symptoms and Common Traits

SM is best understood as an anxiety-based condition resulting in limited verbal communication among individuals, particularly children, who are otherwise verbal in the home or select environments. To diagnose SM, the symptoms of persistent silence in social settings must be present for a least one month, or longer than six months, if it is the first year attending school. The failure to speak cannot be due to a lack of knowledge of, or comfort with, the spoken language required in the social situation. SM is also not an appropriate diagnosis when the failure to speak is due to a primary language or communication disorder or other disorders, such as an autism spectrum disorder. These conditions should be ruled out as needed to make appropriate diagnoses and related treatment recommendations.

In addition to persistent reluctance in speaking, children with SM often exhibit stiff body posture and вЂdeer in the headlights’ facial expressions, inadequate eye contact, and slowness to respond even when there is a clear preference or answer. Individuals with SM may also experience worries, fears, stress, and physical complaints including aches, pains, or discomfort, reluctance to separate from parents or preferred peer(s), sensory sensitivity, and rigid or inflexible behavior.

Within the umbrella of SM, children with this disorder may vary in terms of how they use their voice and body language to communicate with others, ranging from minimal to frequent and appropriate use of verbal and nonverbal behaviors.

Beginning with the most limited communication style, some children with SM may restrict nearly all verbal and nonverbal communication in social scenarios. These children may display a tightly closed mouth, minimal eye contact, and have an expressionless face. This pattern of both limited verbal and nonverbal cues can leave others unsure about what these children are thinking and feeling and most importantly, whether they have any unmet emotional, educational, or medical needs.

Some children with SM may communicate using only nonverbal communication such as nodding, smiling, pointing, writing, signing, or miming. These children may be able to get many of their needs met by nodding to yes/no questions, pointing to answers in a book, and writing to express their ideas; however, prolonged or sole use of nonverbal communication can increase the reliance on nonverbal measures and decrease opportunities for a child to practice, and gain comfort with, speaking.

Other children make sounds and noises (e.g., grunts, mumble, animal sounds) and utterances (e.g., um, uh-huh) instead of intelligible words.

Many children with SM will whisper or use an altered voice, such as using a deeper or higher-pitched voice, a robot or animal voice, etc. Whispering or using an altered voice often places strain on their vocal cords and requires more effort than their typical voice, yet feels less revealing and anxiety-provoking when used.

Some children speak clearly and audibly to certain individuals, and in certain places outside of the home, despite the lack of speech in others.

Selective Mutism Treatment Options

Treatments for selective mutism include psychological/behavioral or pharmacological treatments. However, psychological/behavioral treatments are the first line treatments for selective mutism. Children who do not respond to these treatments might benefit from pharmacological interventions.

Psychological/Behavioral Treatment

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is an evidence-based treatment for childhood anxiety disorders, including SM. CBT focuses on teaching children coping strategies (e.g., modifying “thinking traps”), relaxation strategies, and gradually helping children face their fears (i.e., exposure). Using behavioral principles, clinicians employ strategies like shaping, contingency management, and modeling (e.g., Vecchio and Kearney, 2009), with graded exposure being the most effective.

The gold standard intervention for SM is behavioral therapy (Wong, 2010). Behavioral therapy has the largest supported research base for SM and thus is typically the first recommended treatment option. Behavioral therapy aims to reduce anxiety and avoidance, increase speech and other verbalizations, and reduce oppositionality or negative attention-seeking (Cohan, Price & Stein, 2006). Behavioral techniques include shaping, stimulus fading, behavioral exposures, and contingency management (Bergman, 2013; Cohan et al., 2006).

Behavioral intervention is most often provided in individual therapy or group therapy on at least a weekly or almost weekly basis. Children with SM may also participate in intensive therapy camps, such as Brave Buddies, Mighty Mouth, and Confident Kids Camp, and typically involves approximately thirty hours of behavioral intervention in one week. SM therapy camps are often held in simulated classroom environments and provide field trip activities such as scavenger hunts and visits to local restaurants.

Pharmacological Treatment

Although selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs; e.g., Prozac, Zoloft) are common medical treatments for anxiety and mood disorders, there is limited research in the use of these medications for selective mutism; however, the limited data have shown promising results, especially for children who do not respond to psychological/behavioral interventions (Carlson, Mitchell, & Segool, 2008).

The role of pharmacological methods in the treatment of SM is largely unknown as there are few large-scale experimental pharmacology trials. Most of the research available on medication and SM is based on small samples; however, a recent review pointed to Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) as the most promising medication treatment option for children with SM (Carlson, Mitchell & Segool, 2008). Generally speaking, medication is used as a secondary means of SM treatment if children are not responsive to behavioral therapy. In addition to poor behavioral therapy response, medication may also be indicated when children have severe SM impairment, comorbidities, and/or a strong family history of SM or anxiety. When medication is utilized, the goal is short-term use in conjunction with behavioral intervention. Currently, there are no medications with FDA approval for the specific treatment of SM. It is important to take note of potential side effects when considering utilizing medication in the treatment of childhood SM.

Prevalence and Relevant Background

SM is more common among female than male children, an almost 2:1 ratio (Kumpulainen, 2002; Garcia 2004). The difference between male and female children may reflect an accurate picture, or may reflect bias by social expectations for females to engage in more verbal communication, leading to greater awareness and concern when they do not.

Comorbidities and Associated Factors

At their core, anxiety disorders feature fear, anxiety, and related behavioral factors. It would then make sense that a child with SM who exhibits fear and anxiety about speaking may also experience fear and anxiety in other situations. Children with SM may experience anxiety in social situations, difficulty separating from parents, and fear of specific objects or situations (e.g., bees, the dark), which can result in additional mental health diagnoses. Children with SM may be diagnosed with other anxiety disorders such as social anxiety disorder, separation anxiety disorder, and specific phobias (APA, 2013). The highest comorbidity rates exist with social anxiety disorder with as many as 75-100% of children with SM also meeting criteria for this disorder (Yeganah, Beidel, Turner, Pina, & Silverman, 2003). Given overlapping symptoms and comorbidities, it is important for a clinician to determine if a child’s additional symptoms are due to SM, or if an additional diagnosis is warranted.

SM is also found to be highly comorbid with various communication disorders (APA, 2013). In one study, 32% of children had receptive language difficulties and 66% had deficiencies in expressive language (Klein, Armstrong, Shipon-Blum, 2012). While it is certainly possible for a child to have a communication disorder and SM, an SM diagnosis is not warranted if the lack of speech is directly caused by the communication disorder. There are situations in which these disorders can both be present: for example, if a child does not speak in front of others because of worries about how their communication disorder affects their speech (e.g., “I sound funny”), then a diagnosis of SM may be warranted.

Causes and Risk Factors

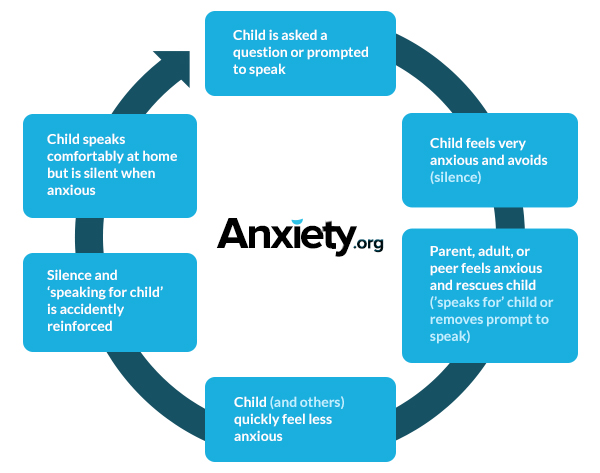

As with most psychological disorders, there is no “one cause” for SM. In fact, SM may be due to a combination of temperamental, genetic, environmental, and neurodevelopmental factors (Muris & Ollendick, 2015). Children with SM are often described as being behaviorally inhibited since infancy (Gensthaler et al., 2016). Broadly, anxiety has a strong genetic basis and tends to run in families, with heritability ranging from 25-50% (Czaijkowski, Roysamb, Reichborn-Kjennerud & Tambs, 2010). Among individuals with SM, 70% have a 1 st degree relative with a history of social anxiety disorder, and 37% have a 1 st degree relative with a history of SM (Chavira, Shipon-Blum, Hitchcock, Cohan, & Stein, 2007). For children with SM, social interactions or settings where speech is expected may trigger the fight-flight-freeze response typical of all anxiety disorders. Further, these reactions or behaviors may then be reinforced when children “escape” the fear-inducing situation by not speaking. This cycle of avoiding speech and subsequent reductions of anxiety may be viewed as an “effective” avoidance technique (Young, Bunnell & Beidel, 2012). Well-intentioned parents, siblings, and others will often вЂspeak for the child’ or remove speaking demands, accidentally reinforcing the child’s silence. See the behavioral conceptualization graphic below.

Research also points to possible differences in the transformation and processing of sound as being linked to SM (Henkin & Bar-Haim, 2015; Muris & Ollendick, 2015). Essentially, parts of the brain and ear may cause children with SM to hear their own voice and other sounds differently than typically developing children. Some additional risk factors for children with SM may include family dysfunction, trauma, school environment, bullying, immigrant status, and social/developmental delays (Muris & Ollendick, 2015), but again it is important to note that none of these risk factors are necessarily a “cause” for the development of SM.

Cultural Differences

To date, cultural differences have not been documented in children with SM. However, one important cultural consideration is differentiating between SM and the period of nonverbal communication (or the вЂsilent period’) that immigrant children experience when learning the host country’s language. When learning a second language, a child typically moves through four well-established stages: 1) persistent silence when expected to speak in the second language, 2) practicing and repeating words in the second language; 3) a вЂsilent period’ of quietly practicing words and phrases in the second language lasting, ranging from weeks to six months; and 4) “going public” with the second language (e.g., Samway and McKeon, 2002). Bilingual immigrant children with SM typically do not progress past stage three, due to worry that they do not speak as well as others, resulting in a prolonged silent period. Symptoms of speaking reluctance might be more evident and persistent in the second language; however, bilingual immigrant children will persistently not speak in situations they are expected to speak, usually affecting both languages. This inability to speak is disproportionate to the child’s language competence and proficiency (Toppelberg & Collins, 2010; Toppelberg, Tabors, Coggins, Lum, & Burger, 2005).

Tips for Parents and Teachers

Parents, teachers, school counselors, school psychologists, and coaches are key players in helping children overcome their selective mutism. Parents are encouraged to share information about SM to other adults, coaches, and family members their child does not speak to. It is also strongly encouraged that parents collaborate with their child’s school to ensure that behavioral strategies and interventions are delivered consistently at school, at home, and after school activities.

If possible, parents should have the child visit the new classroom before the beginning of the school year. The parent should encourage verbal behavior at school so that the child begins to feel comfortable in his/her new environment without the pressure of having other children or adults around. Similarly, have the child meet his/her teacher before the first day of school. The goal is not necessarily to have the child speak to the teacher but should be an opportunity for the child to start feeling comfortable with a new adult. If the child does spontaneously speak, the teacher or the parent should immediately praise the verbal behavior in a simple manner (вЂthanks for telling me’) and quickly redirect back to the topic or activity. It is critical that there be ongoing communication between parents and teachers to assess progress and quickly address barriers to goals. If the child is joining a new after school activity, have the child meet the coach/instructor ahead of time.

Parents can share the following tips with adults and other people the child does not speak to:

Questions to Ask to Find the Right Provider

Recommended Readings and Resources

Websites

Books

Applications

Sources

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM—5. Washington, D.C: American Psychiatric Association.

Bergman, R. L. (2013). Treatment for children with selective mutism: An integrative behavioral approach. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317107.2013.846733

Carlson, J. S., Mitchell, A. D., & Segool, N. (2008). The current state of empirical support for the pharmacological treatment of selective mutism. School Psychology Quarterly, 23(3), 354.

Chavira, D. A., Shipon-Blum, E., Hitchcock, C., Cohan, S., & Stein, M. B. (2007). Selective mutism and social anxiety disorder: all in the family?. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 46(11), 1464-1472.

Cohan, S. L., Price, J. M., & Stein, M. B. (2006). Suffering in silence: Why a developmental psychopathology perspective on selective mutism is needed. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 27(4), 341–355. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00004703- 200608000-00011

Czajkowski, N., Roysamb, E., Reichborn-Kjennerud, T., & Tambs, K. (2010). A population based family study of symptoms of anxiety and depression the HUNT study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 125(1-3), 355–360. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.01.006

Gensthaler, A., Khalaf, S., Ligges, M., Kaess, M., Freitag, C. M., & Schwenck, C. (2016). Selective mutism and temperament: the silence and behavioral inhibition to the unfamiliar. European child & adolescent psychiatry, 25(10), 1113-1120.

Henkin, Y., & Bar-Haim, Y. (2015). An auditory-neuroscience perspective on the development of selective mutism. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 1286-93. doi:10.1016/j.dcn.2015.01.002

Klein, E. R., Armstrong, S. L., & Shipon-Blum, E. (2013). Assessing spoken language competence in children with selective mutism: Using parents as test presenters. Communication Disorders Quarterly, 34(3), 184-195.

Kotrba, A. (2015). Selective mutism: An assessment and intervention guide for therapists, educators & parents. Pesi Publishing & Media.

Kumpulainen, K. (2002). Phenomenology and treatment of selective mutism. CNS drugs, 16(3), 175-180.

Muris, P., & Ollendick, T. H. (2015). Children who are anxious in silence: A review on selective mutism, the new anxiety disorder in DSM-5. Clinical Child And Family Psychology Review, 18(2), 151-169. doi:10.1007/s10567-015-0181-y

Raggi, V. L., Samson, J. G., Felton, J. W., Loffredo, H. R., & Berghorst, L. H. (2018). Exposure Therapy for Treating Anxiety in Children and Adolescents: A Comprehensive Guide. New Harbinger Publications.

Samway, K.D., Mckeon. D. (2002) Myths about acquiring a second language. In: Miller Power B, Hubbard RS., editors. Language Development: A Reader for Teachers. 2. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, pp. 62–68.

Toppelberg, C. O., & Collins, B. A. (2010). Language, culture, and adaptation in immigrant children. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics, 19(4), 697-717.

Toppelberg, C. O., Tabors, P., Coggins, A., Lum, K., Burger, C., & Jellinek, M. S. (2005). Differential diagnosis of selective mutism in bilingual children. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 44(6), 592-595.

Vecchio, J., & Kearney, C. A. (2009). Treating youths with selective mutism with an alternating design of exposure-based practice and contingency management. Behavior Therapy, 40(4), 380-392. doi:10.1016/j.beth.2008.10.005

Wong, P. (2010). Selective Mutism: A review of etiology, comorbidities, and treatment. Psychiatry, 7(3), 23-31.

Yeganeh, R., Beidel, D. C., Turner, S. M., Pina, A. A., & Silverman, W. K. (2003). Clinical distinctions between selective mutism and social phobia: an investigation of childhood psychopathology. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 42(9), 1069-1075.

Young, B. J., Bunnell, B. E., & Beidel, D. C. (2012). Evaluation of children with selective mutism and social phobia: A comparison of psychological and psychophysiological arousal. Behavior Modification, 36(4), 525-544. doi:10.1177/0145445512443980

How to Overcome Selective Mutism

This article was co-authored by Meredith Brinster, PhD and by wikiHow staff writer, Glenn Carreau. Meredith Brinster serves as a Pediatric Developmental Psychologist in the Dell Children’s Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics Program and as a Clinical Assistant Professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at Dell Medical School of The University of Texas at Austin. With over five years of experience, Dr. Brinster specializes in evaluating children and adolescents with developmental, behavioral, and academic concerns, including autism spectrum disorder, developmental delay, intellectual disability, anxiety, attention problems, and learning disabilities. Her current research focuses on early biomarkers of autism spectrum disorder, as well as improving access to care. Dr. Brinster received her BA in Psychological and Brain Sciences from Johns Hopkins University and her doctorate in Educational Psychology from the University of Texas at Austin. She completed her clinical internship in pediatric and child psychology at the University of Miami Medical School and Mailman Center for Child Development. She is a member of the Society for Research in Child Development (SRCD) and the American Psychological Association (APA).

There are 10 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page.

This article has been viewed 194,434 times.

Is your child being affected by selective mutism? This anxiety disorder causes an inability to speak in social situations, even though speaking elsewhere—in private or at home, for example—may be easy. Symptoms usually develop between ages 2 and 4, but selective mutism (SM) can occur in older kids too. While challenging to live with, know that this disorder can absolutely be treated! Read on for a complete guide to understanding and overcoming selective mutism, with tips for minimizing its effects on your child’s social interactions.

Selective mutism

Selective mutism is a severe anxiety disorder where a person is unable to speak in certain social situations, such as with classmates at school or to relatives they do not see very often.

It usually starts during childhood and, if left untreated, can persist into adulthood.

A child or adult with selective mutism does not refuse or choose not to speak at certain times, they’re literally unable to speak.

The expectation to talk to certain people triggers a freeze response with feelings of panic, like a bad case of stage fright, and talking is impossible.

In time, the person will learn to anticipate the situations that provoke this distressing reaction and do all they can to avoid them.

However, people with selective mutism are able to speak freely to certain people, such as close family and friends, when nobody else is around to trigger the freeze response.

Selective mutism affects about 1 in 140 young children. It’s more common in girls and children who are learning a second language, such as those who’ve recently migrated from their country of birth.

Signs of selective mutism

Selective mutism usually starts in early childhood, between age 2 and 4. It’s often first noticed when the child starts to interact with people outside their family, such as when they begin nursery or school.

The main warning sign is the marked contrast in the child’s ability to engage with different people, characterised by a sudden stillness and frozen facial expression when they’re expected to talk to someone who’s outside their comfort zone.

They may avoid eye contact and appear:

More confident children with selective mutism can use gestures to communicate – for example, they may nod for «yes» or shake their head for «no».

But more severely affected children tend to avoid any form of communication – spoken, written or gestured.

Some children may manage to respond with a few words, or they may speak in an altered voice, such as a whisper.

What causes selective mutism

Experts regard selective mutism as a fear (phobia) of talking to certain people. The cause is not always clear, but it’s known to be associated with anxiety.

The child will usually have a tendency to anxiety and have difficulty taking everyday events in their stride.

Many children become too distressed to speak when separated from their parents and transfer this anxiety to the adults who try to settle them.

If they have a speech and language disorder or hearing problem, it can make speaking even more stressful.

Some children have trouble processing sensory information such as loud noise and jostling from crowds – a condition known as sensory integration dysfunction.

This can make them «shut down» and be unable to speak when overwhelmed in a busy environment. Again, their anxiety can transfer to other people in that environment.

There’s no evidence to suggest that children with selective mutism are more likely to have experienced abuse, neglect or trauma than any other child.

When mutism occurs as a symptom of post-traumatic stress, it follows a very different pattern and the child suddenly stops talking in environments where they previously had no difficulty.

However, this type of speech withdrawal may lead to selective mutism if the triggers are not addressed and the child develops a more general anxiety about communication.

Another misconception is that a child with selective mutism is controlling or manipulative, or has autism. There’s no relationship between selective mutism and autism, although a child may have both.

Diagnosing selective mutism

Left untreated, selective mutism can lead to isolation, low self-esteem and social anxiety disorder. It can continue into adolescence and adulthood if not managed.

Diagnosis in children

A child can successfully overcome selective mutism if it’s diagnosed at an early age and appropriately managed.

It’s important for selective mutism to be recognised early by families and schools so they can work together to reduce a child’s anxiety. Staff in early years settings and schools may receive training so they’re able to provide appropriate support.

If you suspect your child has selective mutism and help is not available, or there are additional concerns – for example, the child struggles to understand instructions or follow routines – seek a formal diagnosis from a qualified speech and language therapist.

You can contact a speech and language therapy clinic directly or speak to a health visitor or GP, who can refer you. Do not accept the opinion that your child will grow out of it or they are «just shy».

Your GP or local integrated care board (ICB) should be able to give you the telephone number of your nearest NHS speech and language therapy service.

Older children may also need to see a mental health professional or school educational psychologist.

The clinician may initially want to talk to you without your child present, so you can speak freely about any anxieties you have about your child’s development or behaviour.

They’ll want to find out whether there’s a history of anxiety disorders in the family, and whether anything is causing distress, such as a disrupted routine or difficulty learning a second language. They’ll also look at behavioural characteristics and take a full medical history.

A person with selective mutism may not be able to speak during their assessment, but the clinician should be prepared for this and be willing to find another way to communicate.

For example, they may encourage a child with selective mutism to communicate through their parents, or suggest that older children or adults write down their responses or use a computer.

Diagnosis in adults

It’s possible for adults to overcome selective mutism, although they may continue to experience the psychological and practical effects of spending years without social interaction or not being able to reach their academic or occupational potential.

Adults will ideally be seen by a mental health professional with access to support from a speech and language therapist or another knowledgeable professional.

Diagnosis guidelines

Selective mutism is diagnosed according to specific guidelines. These include observations about the person concerned as outlined:

Associated difficulties

A child with selective mutism will often have other fears and social anxieties, and they may also have additional speech and language difficulties.

They’re often wary of doing anything that draws attention to them because they think that by doing so, people will expect them to talk.

For example, a child may not do their best in class after seeing other children being asked to read out good work, or they may be afraid to change their routine in case this provokes comments or questions. Many have a general fear of making mistakes.

Accidents and urinary infections may result from being unable to ask to use the toilet and holding on for hours at a time. School-aged children may avoid eating and drinking throughout the day so they do not need to excuse themselves.

Children may have difficulty with homework assignments or certain topics because they’re unable to ask questions in class.

Teenagers may not develop independence because they’re afraid to leave the house unaccompanied. And adults may lack qualifications because they’re unable to participate in college life or subsequent interviews.

Treating selective mutism

With appropriate handling and treatment, most children are able to overcome selective mutism. But the older they are when the condition is diagnosed, the longer it will take.

The effectiveness of treatment will depend on:

Treatment does not focus on the speaking itself, but reducing the anxiety associated with speaking.

This starts by removing pressure on the person to speak. They should then gradually progress from relaxing in their school, nursery or social setting, to saying single words and sentences to one person, before eventually being able to speak freely to all people in all settings.

The need for individual treatment can be avoided if family and staff in early years settings work together to reduce the child’s anxiety by creating a positive environment for them.

As well as these environmental changes, older children may need individual support to overcome their anxiety.

The most effective types of treatment are cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and behavioural therapy.

Cognitive behavioural therapy

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) helps a person focus on how they think about themselves, the world and other people, and how their perception of these things affects their thoughts and feelings. CBT also challenges fears and preconceptions through graded exposure.

CBT is led by mental health professionals and is more appropriate for older children, adolescents – particularly those experiencing social anxiety disorder – and adults who’ve grown up with selective mutism.

Younger children can also benefit from CBT-based approaches designed to support their general wellbeing.

For example, this may include talking about anxiety and understanding how it affects their body and behaviour and learning a range of anxiety management techniques or coping strategies.

Behavioural therapy

Behavioural therapy is designed to work towards and reinforce desired behaviours while replacing bad habits with good ones.

Rather than examining a person’s past or their thoughts, it concentrates on helping combat current difficulties using a gradual step-by-step approach to help conquer fears.

Techniques

There are several techniques based on CBT and behavioural therapy that are useful in treating selective mutism. These can be used at the same time by individuals, family members and school or college staff, possibly under the guidance of a speech and language therapist or psychologist.

Graded exposure

In graded exposure, situations causing the least anxiety are tackled first. With realistic targets and repeated exposure, the anxiety associated with these situations decreases to a manageable level.

Older children and adults are encouraged to work out how much anxiety different situations cause, such as answering the phone or asking a stranger the time.

Stimulus fading

In stimulus fading, the person with selective mutism communicates at ease with someone, such as their parent, when nobody else is present.

Another person is introduced into the situation and, once they’re included in talking, the parent withdraws. The new person can introduce more people in the same way.

Shaping

Shaping involves using any technique that enables the person to gradually produce a response that’s closer to the desired behaviour.

For example, starting with reading aloud, then taking it in turns to read, followed by interactive reading games, structured talking activities and, finally, 2-way conversation.

Positive and negative reinforcement

Positive and negative reinforcement involves responding favourably to all forms of communication and not inadvertently encouraging avoidance and silence.

If the child is under pressure to talk, they’ll experience great relief when the moment passes, which will strengthen their belief that talking is a negative experience.

Desensitisation

Desensitisation is a technique that involves reducing the person’s sensitivity to other people hearing their voice by sharing voice or video recordings.

For example, email or instant messaging could progress to an exchange of voice recordings or voicemail messages, then more direct communication, such as telephone or Skype conversations.

Medicine

Medicine is only really appropriate for older children, teenagers and adults whose anxiety has led to depression and other problems.

Medicine should never be prescribed as an alternative to environmental changes and behavioural approaches. Though some health professionals recommend using a combination of medicine and behavioural therapies in adults with selective mutism.

However, antidepressants may be used alongside a treatment programme to decrease anxiety levels, particularly if previous attempts to engage the individual in treatment have failed.

Advice for parents

Getting help and support

Teenagers and adults with selective mutism can find information and support at iSpeak, Finding Our Voices and the Facebook group SM SpaceCafe.

The Selective Mutism Information and Research Association (SMiRA) is another good resource for people affected by selective mutism. There’s also a SMiRA Facebook page.

The Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists and the Association of Speech and Language Therapists in Independent Practice can help you find professionals in your area with experience in treating selective mutism.

Page last reviewed: 27 August 2019

Next review due: 27 August 2022

Selective Mutism in adults (A Comprehensive Guide)

OptimistMinds

As a BetterHelp affiliate, we may receive compensation from BetterHelp if you purchase products or services through the links provided

The world has seen a lot of disabilities in terms of physical ones and also mental disabilities.

Some of these disabilities are well-known for ages but some of these disabilities are rather new.

Language and communication disorders have been classified in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Disorders.

They are now classified separately as compared to before when they were under the domain of childhood disorders.

One of the communication disorders which is rather new and rare is known as selective mutism.

We are going to discuss selective mutism in this article. Selective mutism is often considered as a childhood disorder which is true to an extent but it is not always true because adults can also suffer from selective mutism.

It is mainly called so because it is diagnosed in childhood mostly when a child starts going to school.

Not many people know what happens to selective mutism (SM) when the child goes into adolescence or becomes an adult.

Selective mutism rarely goes away if it is not treated properly.

People don’t just grow out of it because there are many people who are trying to get over it but can’t.

Let’s discuss complications of selective mutism in adults but before that, we have to know what selective mutism is?

Selective mutism can be defined as “a severe anxiety disorder in which a person cannot speak in a specific social situation”.

We can take the example of a person who is not able to speak if he comes in front of the whole class or to relatives they are not much familiar with.

It often starts during childhood years and it can go for long years if not treated properly.

In the case of selective mutism, a child does not have control over him not speaking at a specific situation as he does not refuse to speak.

The situation in which the child has to talk to certain people often accompanies a freeze response along with feelings of panic just like a case of really bad stage fright where the person stops talking completely.

Once the person starts anticipating the situation he just starts avoiding the situation altogether.

These people tend to speak with other people they are comfortable with like their close friends and family members.

Selective mutism affects almost 1 in 140 young children and it is found more common in girls than in boys.

It is also found more common in children who are trying to learn a second language like children who have migrated to another country from their home country.

If you are worried about your child or any other person around you is suffering from selective mutism and you want to know for sure if that is the case then you should look for the following signs in them.

These signs are for adults as well as children who are almost 2 to 4 years old because it is often noticeable when a child starts interacting with people other than the family members like when they do while going to school or a preschool.

You would definitely see a visible and significant difference in a person or child’s ability to talk to certain people.

They will give frozen facial expressions when they are about to talk to someone whom they are not familiar with.

They avoid eye contact and often appear to be.

Some people with a higher level of confidence often use gestures and signals to communicate as they may nod or shake their heads when they are trying to say yes or no respectively.

However, others with low confidence often avoid communication and do not use any kind of gestures and just go completely quiet.

Yet other people, as well as children, may use an alternate form of communication like whispering or saying a few words.

There are a few theories that have been doing rounds about the causes of selective mutism but nothing can be said for sure.

Some of the causes of selective mutism are given below.

Phobia is considered as one of the main causes of selective mutism and the answer to what causes selective mutism in adults.

Selective mutism is often associated with anxiety even if the cause is not always clear.

The person will have a tendency towards anxiety and mostly have difficulty while doing everyday chores and work.

People often feel anxious in certain situations and that’s why they go completely quiet and mute while talking to certain people.

If the person is also suffering from some kind of speech or communication problem, it will only make things worse and make the speaking even more problematic and stressful.

Other people have trouble processing loud noises or jostling from crowds because they have a problem in processing sensory information.

That’s why they just shut down and do not speak when the environment around them becomes overwhelming.

Their anxiety gets transferred to the people around them.

Selective mutism can also occur as a symptom of post-traumatic stress and it does not follow the usual pattern of selective mutism.

In this case, people often go quiet in the environment and people who are already familiar.

In that case, they did not have difficulty talking in those environments or to those people before the traumatic event happened.

It occurs rarely but it has occurred and it is reported as one of the causes of selective mutism.

This first occurs only as a speech withdrawal and if the problem is not addressed then the person can develop full-fledged selective mutism.

Moreover, the person can develop even more anxiety about general communication as a result of post-traumatic stress.

Some people have also listed that autism can be a potential cause of selective mutism or a child can be autistic if he has selective mutism.

Parents have often seen children as manipulative and controlling when they actually have selective mutism.

A child can develop both but there is no relationship or causal link in autism and selective mutism.

Selective mutism in adults can cause severe problems if it has not gotten proper attention and it can lead to a person making him isolated, suffering from low self-esteem, and even social anxiety.

It can also cause problems in occupations and relationships.

It is of utmost importance that the person is properly diagnosed and treated with the same caution as any other mental disorder.

The diagnostic guidelines for the diagnosis of selective mutism in both children and adults are given below.

Children become successful adults if selective mutism is treated in the early stages.

School staff and parents need to come together to save children from selective mutism.

You need to go to a speech and language therapist in order to get your child diagnosed appropriately for selective mutism.

You can talk to the therapist about every need as well as the anxiety from which the child is suffering.

The therapist will look at behavioral and family issues as well even if the child doesn’t speak to the parents he should be encouraged or the parents should tell everything.

Adults can overcome selective mutism but they may keep experiencing psychological and practical effects of years they have spent without any social interaction or not being able to achieve academically or occupationally what they wanted to achieve.

Adults can be seen by a mental health professional who can get support from a speech and language therapist or another knowledgeable mental health professional.

If a child suffers from selective mutism, he or she can be treated if they are diagnosed on time and with appropriate guidelines.

Handling appropriately is very important, once they are diagnosed, a mental health professional needs to work on the treatment guidelines and how to deal with a selective mutism patient.

For an effective treatment, the mental health professional needs to know about the length of selective mutism as well as any additional difficulties associated with it.

Moreover, support and cooperation with school staff and other members is also of utmost importance.

There are the following treatment options available for children and adults suffering from selective mutism.

The most effective types of treatment are cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and behavioral therapy.

As the name represents, this therapy focuses on a person’s cognition and how they think of themselves.

CBT also helps the person face the challenges and fears by using graded exposure.

It is probably the best therapy for adults and it can also be used for older children and not for younger ones.

For instance, CBT may include talking about anxiety and understanding how it affects their body and behavior and learning a range of coping strategies for anxiety or other anxiety management techniques.

The name shows that this therapy is used to reinforce the desired behavior and replace inappropriate behavior with an appropriate one.

It does not deal with thoughts or past and it provides a step by step approach to help the person overcome his fears.

Different techniques of behavior therapy used for selective mutism are as follows

Other treatment options for selective mutism can be medicines and mostly applied to children and not adults.

However, they are in no way alternative to the therapies mentioned above.

Side Note: I have tried and tested various products and services to help with my anxiety and depression. See my top recommendations here, as well as a full list of all products and services our team has tested for various mental health conditions and general wellness.

FAQ about What is selective mutism in adults

What could members of the social support group do for a person to overcome selective mutism?

Do not pressurize the sufferer and just encourage them to speak.

Let them know that you understand their predicament and really there to help.

However, don’t praise them for speaking in public either.

Verbal assurance, love, support, and patience are necessary.

What triggers selective mutism?

Causes are still unknown but they are mostly related to anxiety.

Can selective mutism be cured?

If it is treated right, the prognosis could be promising considering other factors like social support and lack of other complications are well

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/ArlinCuncic_1000-21af8749d2144aa0b0491c29319591c4.jpg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/aron-6f9b8a651e804c07b290e57b3218a898.jpeg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/GettyImages-153936852-56b1837b3df78cdfa0021a26.jpg)