How to make a game engine

How to make a game engine

Making Your Own Video Game Engine: The Beginners Guide

When I first started gaming, I definitely took for granted what all went into creating them. I simply thought people got together in a secret room, made graphics, and put them together. Little did I know that even some of the simplest animation and games be Herculean tasks for developers.

Much more goes into a game than just graphics and story. Do you need a game engine to make a game? You don’t necessarily. You can also make a game by way of coding. But where’s the fun in that?

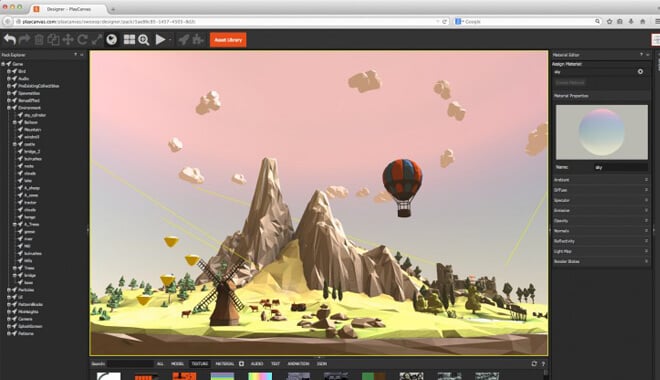

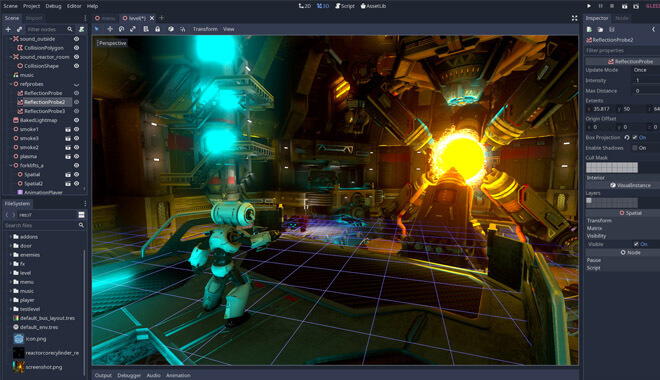

The game engine is the foundation for how things will react and respond in the game, so having the right one for your idea is crucial. You have great options like Unity and even the Unreal engine, but what if you wanted to make your own?

Is it even possible? I am here to say that yes: it absolutely is.

Now, this isn’t the same as having a great idea for a project and just rolling with it. No, no, no, my friend. This is an investment in which you will most likely end up pouring hundreds if not thousands of hours.

Think of all those hours in Witcher 3 and Red Dead Redemption times a hundred, no, a thousand.

Not only that, but you’ll have to have a nuanced and knowledgeable skillset to even begin to tackle this task. Not that it can’t be done, but rather you need the right people, background, and passion for the game engine you want to develop.

Table of Contents:

Why Build an Engine?

Should you make your own game engine? This is the big question, isn’t it? Why do you want to build a game engine? Is it to try and make something on your own?

Maybe something that doesn’t need Unreal or Unity? If one were to harness the power of a game engine, the creative potential going forward is immense.

You aren’t exactly pigeonholed either; you can make a game engine teach code to users, be geared towards beginners and veterans of the craft, and scratch that itch that hobbyists get. You may ask yourself truly, what is a game engine?

What goes into a game engine? Well, building a game engine isn’t easy work; if it were so, everybody and their brother would have done so. Instead, it takes time and patience, something that a lot of gamers, (myself certainly included), can sometimes have a short supply of.

Making a game engine could be an extremely interesting and beneficial asset to your development portfolio. How impressive would it be to see under someone’s projects that they were/are developing or making a game engine?! I kneel before them in awe.

You need to have a good grasp of what engines are. For example, you might get things mixed up. Is OpenGL a game engine? No, it’s more of a graphics renderer, not an engine.

The possibilities of the ‘why’ can be endless. Let’s stick to some more concrete things, like some simple pros and cons right off the bat.

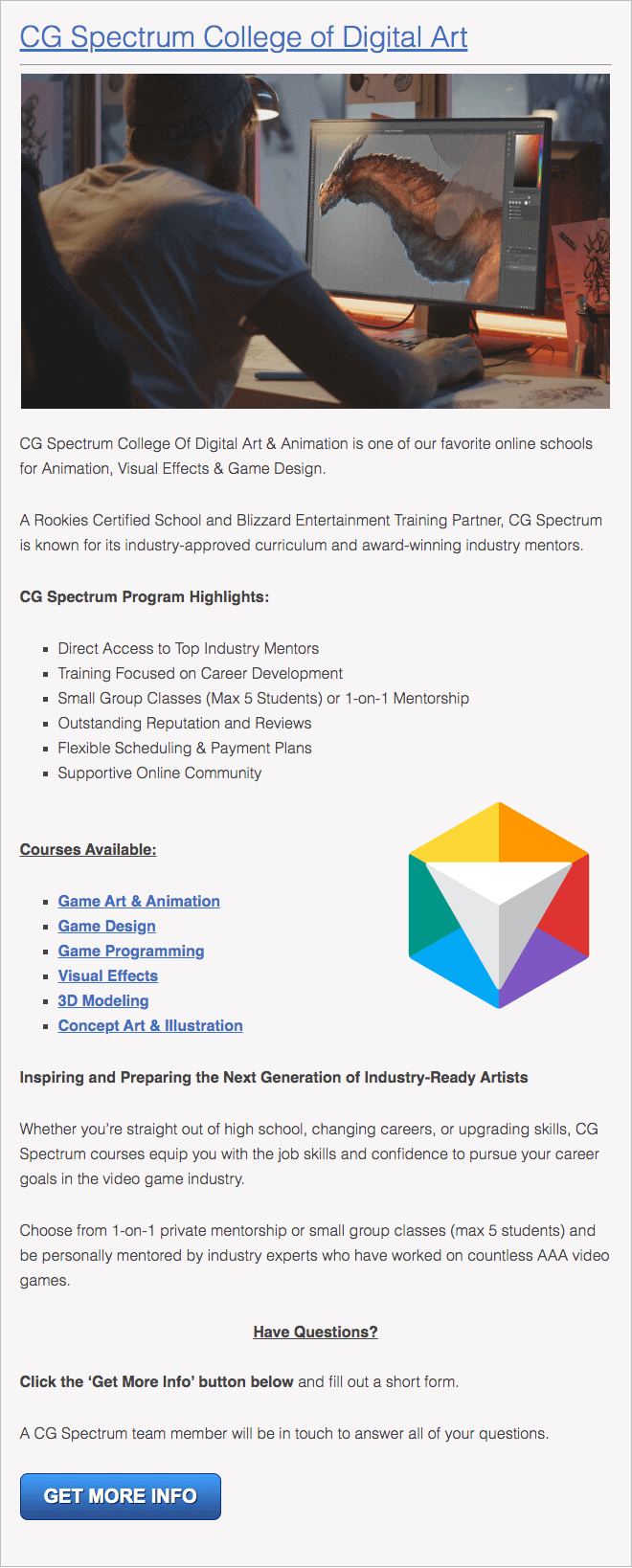

Featured Coding School

Pros and Cons of Building a Game Engine

Creative potential

Creating a game engine is more or less creating the building blocks for a potential living, breathing world. This could range from something simpler like the bloody pixel-fest Hotline Miami, or the more complicated projects like a AAA title.

You more or less have control of where you want to ‘go’ creatively, only being bound by your resources. For artists and other creatives, this is a pretty huge pro.

A user on Quora, when asked about the rigors of game engine development, gave some great insights, and ended his post by saying that it was all worth it:

“The day when I saw my game engine work for the first time, I cried, I jumped, and I danced out of joy because in that instant I gained something more valuable than money and success.”

That should be enough for some people. I know it is for me!

Meeting fellow creators

In your quest to make your own game engine, you will no doubt run into many different colorful characters inhabiting the internet, doling out help, tips, and tricks. This pipeline to the community of fellow gamers and developers can be key, as we will learn a little later.

Control

You have complete control of everything in your engine. You know how it works, doesn’t work, what could be better, and more.

This can be invaluable as since you know everything there is to know about the engine, you are the best source of help with every aspect, like animation and physics.

Learning experience

Making a game engine will throw you through the wringer, and your experience will grow exponentially from it. Even if you don’t end up with your dream project, the potential to learn from mistakes and failures is what it’s all about sometimes.

As I said before as well, you can add these experiences to your portfolio going forward as well. It’ll be pretty impressive to see someone with your experience joining a team or working on a project.

Significant Time Sink

Guys, as I said before, you will spend countless hours developing an engine. This, unfortunately, isn’t exactly a casual romp that people can just float their way through over the course of a weekend. You’ll likely be spending months and years building your engine even before it is fully operational.

Ariel Manzur and Juan Linietsky, the developers of the Godot engine, have constantly been updating Godot since its launch in the mid-2000s. Keep in mind that after you launch, you will most likely have to keep working and working well after the launch date to keep your engine running smoothly.

This ties into the community, and hopefully resources will be plenty and available. Many have said that this may be one of if not the biggest factors on why NOT to make a game engine.

Steep Learning Curve

If you aren’t familiar with a lot of game designing terms and concepts, this will be a big roadblock for you. Game engine development deals, at its very base, with a multitude of deep concepts, and can easily leave uninitiated developers fuming and frustrated.

You need to be in the right mindset and right level of comfortability with gaming, game development, and technical skills to begin on the long, yet rewarding journey of making a game engine. It isn’t recommended for first-time developers.

Other engines

Many online say that it is just flat out easier to use an existing engine to develop a game or creative project rattling around in your brain.

I mean, it’s pretty easy to fall into this category since there are a slew of other engines with their own unique and attractive styles that could make your life easier

Now that we got that out of the way, let’s focus more on the basics, namely what you’ll need to start this ambitious journey.

Languages and Experience: Learn to Code

No, not languages like Spanish; I’m talking coding languages of course! Making a game engine isn’t easy as we all are now aware, so having a basic knowledge of different coding languages is an absolute must.

C++ is the lifeblood of programming. If you’re a C++ master, then game development and engine building could fall into your lap more easily.

However, if you’re a newbie at programming and coding, C++ isn’t a monumental task to undertake. If you are dead set on making a game engine, you have to fully commit to every aspect.

C++ is a great first thing to jump right into. It runs on nearly all platforms and is used with almost everything you will come across. It’s the virtual blood flowing through the veins of your creative game engine. Once you learn enough of C++, you can branch further out. For example, Java is one of the most famous and popular coding programs ever made.

Java is a derivative of the C++ language. It’s simpler, making developing with Java a breeze. It pares down some of the more complicated aspects of C++ and makes the syntax and terms easier to digest.

If you wanted your game engine to harness Java, then this might be the path for you.

I found some great options for places to learn how to code for free these days, so don’t fret:

These great options can take you from a bumbling beginner to keyboard samurai. Many include great communities and courses to make you less uncomfortable and make you a coding master.

Not only that, but many are e-learning platforms for a multitude of subjects. You could explore more about game engine design by exploring many of its related computer-related fields.

Basically, C++ is pretty much necessary and drives many of today’s engines as an important part of the design process.

How to Structure Your Project

All of this in mind, where do you even begin? How do you manage time effectively? It’s no walk in the park, my friend, but you can easily hone down your work hours as well as stress if you follow some simple steps.

Have a System

Any system. This means anyway that you personally work best in your developing environment. Maybe that means ‘Wake up early, code all day, go to sleep’ to you.

It could also mean ‘work two jobs and come home and code’. It will be different for everyone undertaking to develop a game engine from scratch.

Along with this is a realistic goal setting. Of course, when we start projects, we want to shoot for the moon. However, most times that just isn’t a reality and you have to modify your system.

Long term goal setting can be a healthy, productive way for you to build an engine quicker, and with more efficiency.

Think of a goal in engine building as the finish line of a marathon. How will you personally get there? Will you run in your free time to practice getting better at running? Will you just sprint and hope for the best?

Having a system is all at once having so many things and filtering it down into a lifestyle and mindset. Find what works for you and your goals best without burning you out.

Consider Collaboration

This is one of my favorite ideas in development. Why go it alone? In-game and engine development, going solo can quickly become frustrating and irritating beyond belief.

Luckily, there are boatloads of talented individuals at your disposal. Whether they be friends, coworkers, or strangers you found on the Internet, someone to bounce ideas off of and collaborate with could give you a huge boost towards your goals. Communities online, in particular, are breeding grounds for some seriously talented game and engine developers,

who likely have the same drive and creative juices that you do. Subreddits and Steam forums are some great places to get your feet off the ground. Steam has community hubs in which modding, and configuration are the talk of the town.

Contacting any number of these people could yield some impressive results. I play a hell of a lot of Total War games, and I have a bunch of mods downloaded.

I bet if I contacted the developers of the famous Darth Mod, I could receive some valuable insight; it’s that easy. The two Godot developers had each other, and it’s a huge reason they even launched Godot in the first place.

So, basically, don’t be afraid to team up with some like-minded developers who may share a similar dream and drive as you. Bouncing ideas off of one another is also something you’re going to need when making a game engine.

Use an iterative approach

An iterative approach to something, (namely software development), works in phases, emphasizing incremental builds of a development. More specifically, it helps those in software learn easily from different aspects of the software build from before.

Your first stage is the initial planning and regular planning, where your ideas come into play. Then, the analysis and design, in which you actually put your project to the software, analyze and see if the design holds up. Then you put your design to the test, observing closely what went wrong or right, and how to fix any nuisances.

Finally, you evaluate what happened with your project. After this, the cycle begins anew, where you have all of the data from all of the testing, and now you can incrementally build on your results.

It can prove to be extremely useful and effective, especially with game engine development. You want to be present every step of the way, at every stage of development.

As stated above, you need to know how it all works. This is your world; you need to live in it.

Don’t try to do it all

Starting out, you may be tempted to dive right in. But beware; it can be easy to take on a load that’s too large for you at this present moment. You need to work slowly, (as frustrating as that could be), gathering all the info you can, and maximizing your workflow.

This ties into collaboration as well, as you can gather a team and delegate duties to different members, taking the burden of the entire project off of your shoulders.

If you use goal-setting in tandem with the iterative approach, you could be surpassing goals left and right. However, trying it all will quickly overload even the most seasoned developer.

Nothing is gained from you getting too confident and abandoning your project out of frustration.

Aspects of the Game Engine

How are video game engines made? They consist of many interlocking parts. The game engine contains everything needed for a game to run. all of those favorite games of yours were built-in engines that harnessed the developer’s idea into the main working parts:

Are You Going to Build?

Well, are you? You’ve seen the pros and cons, the many different aspects of what goes into the process. You will need a lot of knowledge, extreme determination, and passion for building a game engine.

What I want to impart most of all is to not be afraid to fail. In the worst-case scenario, you could leverage your portfolio, touting your impressive software development skills.

But if you set realistic goals, don’t burn out, and get a great team of like-minded individuals behind you, in a few years’ time, you could have the new Godot engine.

How I made a game engine from scratch?

The text below was originally posted on SDSLabs’ blog site which is a group of college students that like to make digital products. I should mention that I was a complete beginner when I started. I only had a handful of gamedev experiences before starting and I built away from that. Also, I will be referring to SDSLabs whenever I say ‘we’ or ‘us’.

Today we are proud to announce ‘Rubeus’! Rubeus is an open-source 2D game engine written purely in C++17 and is designed with a vision to inculcate the spirit of game development amongst the general public (specifically the IIT Roorkee junta). You can check out Rubeus at https://github.com/sdslabs/Rubeus.

What is a game engine? How is it different from a game?

A game engine, in its most mature form, is a platform that provides tools and utilities to game developers for designing and developing games based on their ideas.

To provide some comparisons, some of the most well-received games in the market have been Ubisoft games from the likes of the Assassin’s Creed franchise and the Watch_Dogs franchise. These games look and feel very similar to each other as both of these franchises have a stealth mechanic deeply rooted at their heart.

The stealth mode mechanic in Watch_Dogs 1 takes a whopping 100,000 lines of code in the game. It is not only economically impossible to regenerate and reintegrate that much amount of code for each and every game that gets released under the franchise, but would also take up a lot of the developers’ time. This is why Ubisoft has engraved the stealth mechanic in their game engine and they keep reusing it in their newer games with appropriate modifications.

Why make an entire game engine and not a game?

In reality, the development of most games at game studios starts with developing a game engine first. Creating a game without a game engine can be considered as hard-coding functionalities in a crude form. This means that if you happen to work on another project (perhaps a sequel of the previous game), you will have to again work on laying down the basic layer of functionalities that all types of games work on. It is likely that whenever you start working on a new project, a significant part of your code will be repeated every time. This practice of writing the same code every time you work on a new game is incredibly inefficient and this is a problem that we, at SDSLabs, intend to solve.

Making a game engine is a complex task and this is why most casual developers overlook the possibility of using a game engine to realize their game ideas. However, there are a lot of free alternatives out in the market. For example, you might have heard about Fortnite and the latest Tekken 7, both of which run on Epic Games Studio’s Unreal Engine 4. It has, in fact, made it possible for the Tekken franchise to finally hit the PC market. There are plenty of game engines out there but we decided to put ourselves up to the challenge of creating one for ourselves and releasing it to the public for everyone to use.

How to even start with making a game engine?

The starting days of Rubeus in the month of May 2018 were full of reading sessions. The best websites to look up information on topics that we found were related to game development are probably Gamedev.net and Gamasutra. We also recommend following r/gamedev on Reddit, which is a booming community of game developers from both indie and AAA studios.

The beginning of something amazing

One of the first hurdles that we faced was how we should implement the Rubeus engine’s architecture. We had zero levels of abstraction in our codebase and we were trying to create an API out of it that should be useful to even a newbie. This made us take a step back and we started to work on the individual modules of the engine rather than the API.

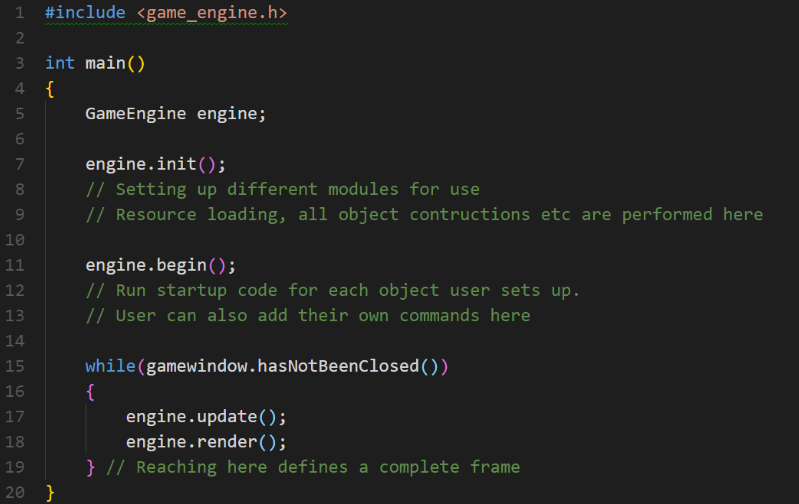

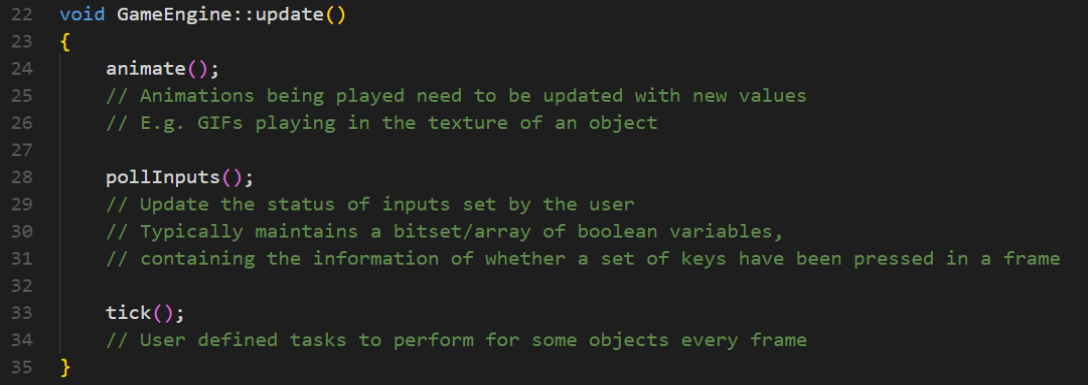

Any game engine works on a concept of what is known as the ‘Game Loop’. In the most general sense, games are recurrent programs. They do not normally shut down after their execution is complete. Instead, they often keep on repeating a particular set of instructions over and over unless the game shuts itself down or when the player has pressed the QUIT button. This is the concept of an ‘Application Loop’.

Now, let us see how game engines modify this concept so as to suit most closely to an actual game. A general game engine loop looks a bit like this:

The engine update function above consists mainly of the physics engine update and the calling all the tick functions.

A tick function is some user-defined logic that the user wants to run at every frame in the game. It may contain all of the game logic or just a frame counter to measure the FPS. Coming to the physics engine update, it is also just a function that gets called once every frame but it checks for collisions every frame, and if it finds any collisions happening then it defines what change of velocities of the colliding game objects take place in that frame.

The most important parts of making a game engine are implementing the physics update function and the render function (also known as the drawing step). These two functions are implemented independently inside the physics engine and the rendering engine. The render function just renders the scene. It applies no game logic to the scene. All logic is covered inside the update functions. Render functions tend to take care of what visual effects the user requires at a certain moment in the game.

A typical single-threaded game engine update loop should look like this:

Taking all these bits of information together, we started building Rubeus function by function. We first listed down the basic components of a game engine. To give a gist of how and what we started to work on, below is some documentation on our process of building a game engine.

Graphics Components:

A window module that talks to the OS and generates a window which allows OpenGL drawings to be rendered on the screen

This had to be done in an OS-independent way because to keep the engine cross-platform. One such library that eases this task is GLFW(“OpenGL Framework”). GLFW makes the task of drawing to the screen independent of the OS using OpenGL completely hassle-free.

A rendering module that abstracts all objects appearing in the game with the specific image/color that they use to get rendered to the screen

It is also the renderer’s job to use the specific shaders that allow the objects to get colored in a way that the shader governs. In a nutshell, shaders are bits of code (written in OpenGL Shading Language a.k.a. GLSL, in our case) that tell the GPU where each vertex is present in the 3D space and what sort of algorithms should be used to color every pixel along with what sort of effects should be applied to the rendered image.

For example, 3D games nowadays have started using a ‘Bloom’ effect to highlight bright objects on the screen.

Bloom effect is a lighting illusion that is used to make objects appear brighter than the maximum brightness of the monitor.

This particular effect i.e. Bloom effect is implemented inside shaders and the renderer uses these shaders to output graphics on the screen.

During the development of Rubeus’ renderer, that we proudly named the ‘Guerrilla Renderer’, we ran a benchmark at rendering 14,560 sprites (a.k.a. 2D objects) at 450 FPS on a GTX 1060 (6GB). We tried to crank the numbers higher and somehow managed to choke our own engine by displaying 122,300 sprites at 4 FPS. A quick reminder: No real-life game ever reaches these numbers of objects being displayed at a time. We had also tested Guerrilla only in Debug mode without any form of inlining of C++ code.

This is a test run from another benchmark that we ran.

Multithreading:

We were aware of the fact that even if we may not ever make Rubeus multithreaded in the first place, we may require the need to perform asynchronous responses such as implementing a console, or a debug menu for the user that use Rubeus to make a game for their players.

Multithreaded programs are exactly what they sound like. They are able to follow more than 1 flow of execution of code at a certain moment in time. Beware that such systems can be incredibly hard to build because improper sharing of resources and also just overuse of threading will also give a negative hit to the performance of the engine.

We have implemented a multithreaded messaging system inside Rubeus that we plan to release in v2.0. More information on this type of architecture can be found in this wonderful article about making different types of game engine architectures.

By the time we were done with the multithreading architecture and the Guerrilla renderer, it was already mid-July and we had started to realize that this project might take a while to get completed. Not because of any lack of development times but the sheer size of this project. It was about time we started to really speed things up or Rubeus would be seeing the light of the day not before 2019 or maybe even not at all.

A Physics Engine:

Rubeus’ physics engine, nicknamed ‘Awerere’ (pronounced as “auror”) is also what it sounds like. Awerere is a physics engine that works inside Rubeus and allows simulation of life-like collisions and physics of game objects.

The physics engine is an essential part of bringing any form of realism in a game. It is responsible for figuring out what objects are colliding with each other, what objects are not colliding with each other and if they are colliding, what velocities do they move away with and if they have collided, should they repel like rigid bodies or do they release some form of energy (likes of what we see in inelastic collisions amongst rigid bodies).

All these questions are what the physics engine has to find the answers for. Sometimes the user can define some customized response to collisions. For example, the user would like to open a door to another doorway if the player shoots a particular switch on the wall.

Currently, Awerere supports shapes such as boxes, circles, and planes. It handles collisions amongst all of the permutations of these objects and assigns them their final physical state after the collision. Designing Awerere and implementing the different collision algorithms was a treat because we personally like studying and realizing rigid body physics with the help of real-world physical laws.

Inputs and Sounds Manager:

In this part of the development cycle, we were slowly approaching the release date and we had already implemented and debugged the hard parts of implementing a physics engine.

We have used the popular ‘Simple and Fast Multimedia Library’, often known as just ‘SFML’ to provide Rubeus with cross-platform access to the sound devices in an organized sound manager. Rubeus now supports loading both long audio tracks like ambient and background music in addition to short pieces of audio like footsteps, gunshots, etcetera.

When we had selected GLFW for generating windows on all OSs, we also had to keep a note of how GLFW handled getting inputs from the input devices. It also provides keyboard presses along with mouse button presses, scrolling, and just plain cursor positions. But all of this is done in an asynchronous response that GLFW provides the engine. We have implemented a system that keeps track of what keys have been pressed and what keys have been released at the starting of every frame. This made up the base of creating the Input manager which we further abstracted to work by creating keybindings for each control. Multiple keys are now assignable to a single keybinding/control.

Bringing everything together

Near the end of November we were ready with all subsystems and modules that were required to make up Rubeus. But we still did not have an API or a gateway that the user could interact with.

This is when we came up with broCLI, which stands for ‘Rubeus on Command Line Interface’. broCLI is a CLI tool implemented in Golang which helps create a project structure for Rubeus. It was the perfect idea for Rubeus to use a CLI tool instead of a GUI so that users get a feeling of doing some heavy work while working with Rubeus. The user persona for Rubeus was always a beginner programmer from the start of May 2018. A CLI is probably something that they will be seeing a lot in their coming days.

Rubeus may have a GUI later but for v1.0, we are focusing only on a CLI.

Fast forward to this day

We are happy that we were able to implement such a complex piece of technology with elegance and now, we invite others to partake in this endeavor into the realms of game development.

Preshing on Programming

Preshing on Programming

Lately I’ve been writing a game engine in C++. I’m using it to make a little mobile game called Hop Out. Here’s a clip captured from my iPhone 6. (Unmute for sound!)

Hop Out is the kind of game I want to play: Retro arcade gameplay with a 3D cartoon look. The goal is to change the color of every pad, like in Q*Bert.

Hop Out is still in development, but the engine powering it is starting to become quite mature, so I thought I’d share a few tips about engine development here.

Why would you want to write a game engine? There are many possible reasons:

The gaming platforms of 2017 – mobile, console and PC – are very powerful and, in many ways, quite similar to one another. Game engine development is not so much about struggling with weak and exotic hardware, as it was in the past. In my opinion, it’s more about struggling with complexity of your own making. It’s easy to create a monster! That’s why the advice in this post centers around keeping things manageable. I’ve organized it into three sections:

This advice applies to any kind of game engine. I’m not going to tell you how to write a shader, what an octree is, or how to add physics. Those are the kinds of things that, I assume, you already know that you should know – and it depends largely on the type of game you want to make. Instead, I’ve deliberately chosen points that don’t seem to be widely acknowledged or talked about – these are the kinds of points I find most interesting when trying to demystify a subject.

Use an Iterative Approach

My first piece of advice is to get something (anything!) running quickly, then iterate.

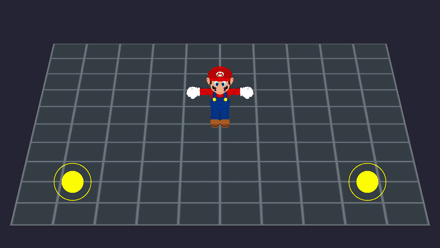

My next step was to download a 3D model somebody made of Mario. I wrote a quick & dirty OBJ file loader – the file format is not that complicated – and hacked the sample application to render Mario instead of a cube. I also integrated SDL_Image to help load textures.

Then I implemented dual-stick controls to move Mario around. (In the beginning, I was contemplating making a dual-stick shooter. Not with Mario, though.)

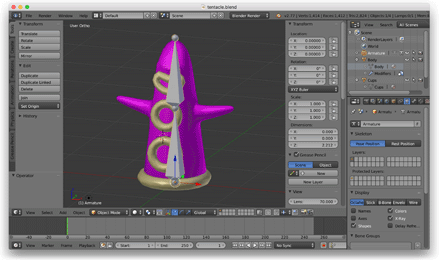

Next, I wanted to explore skeletal animation, so I opened Blender, modeled a tentacle, and rigged it with a two-bone skeleton that wiggled back and forth.

At this point, I abandoned the OBJ file format and wrote a Python script to export custom JSON files from Blender. These JSON files described the skinned mesh, skeleton and animation data. I loaded these files into the game with the help of a C++ JSON library.

Once that worked, I went back into Blender and made more elaborate character. (This was the first rigged 3D human I ever created. I was quite proud of him.)

Over the next few months, I took the following steps:

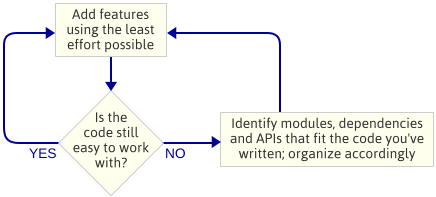

The point is: I didn’t plan the engine architecture before I started programming. This was a deliberate choice. Instead, I just wrote the simplest code that implemented the next feature, then I’d look at the code to see what kind of architecture emerged naturally. By “engine architecture”, I mean the set of modules that make up the game engine, the dependencies between those modules, and the API for interacting with each module.

This is an iterative approach because it focuses on smaller deliverables. It works well when writing a game engine because, at each step along the way, you have a running program. If something goes wrong when you’re factoring code into a new module, you can always compare your changes with the code that worked previously. Obviously, I assume you’re using some kind of source control.

I would argue that more time is wasted in the opposite approach: Trying too hard to come up with an architecture that will do everything you think you’ll need ahead of time. Two of my favorite articles about the perils of over-engineering are The Vicious Circle of Generalization by Tomasz DД…browski and Don’t Let Architecture Astronauts Scare You by Joel Spolsky.

I’m not saying you should never solve a problem on paper before tackling it in code. I’m also not saying you shouldn’t decide what features you want in advance. For example, I knew from the beginning that I wanted my engine to load all assets in a background thread. I just didn’t try to design or implement that feature until my engine actually loaded some assets first.

The iterative approach has given me a much more elegant architecture than I ever could have dreamed up by staring at a blank sheet of paper. The iOS build of my engine is now 100% original code including a custom math library, container templates, reflection/serialization system, rendering framework, physics and audio mixer. I had reasons for writing each of those modules, but you might not find it necessary to write all those things yourself. There are lots of great, permissively-licensed open source libraries that you might find appropriate for your engine instead. GLM, Bullet Physics and the STB headers are just a few interesting examples.

Think Twice Before Unifying Things Too Much

As programmers, we try to avoid code duplication, and we like it when our code follows a uniform style. However, I think it’s good not to let those instincts override every decision.

Resist the DRY Principle Once in a While

95% of the time, re-using existing code is the way to go. But if you start to feel paralyzed, or find yourself adding complexity to something that was once simple, ask yourself if something in the codebase should actually be two things.

It’s OK to Use Different Calling Conventions

One thing I dislike about Java is that it forces you to define every function inside a class. That’s nonsense, in my opinion. It might make your code look more consistent, but it also encourages over-engineering and doesn’t lend itself well to the iterative approach I described earlier.

Then there’s dynamic dispatch, which is a form of polymorphism. We often need to call a function for an object without knowing the exact type of that object. A C++ programmer’s first instinct is to define an abstract base class with virtual functions, then override those functions in a derived class. That’s valid, but it’s only one technique. There are other dynamic dispatch techniques that don’t introduce as much extra code, or that bring other benefits:

Be Aware that Serialization Is a Big Subject

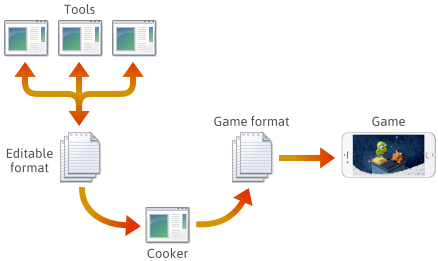

Serialization is the act of converting runtime objects to and from a sequence of bytes. In other words, saving and loading data.

When setting up such a pipeline, the choice of file format at each stage is up to you. You might define some file formats of your own, and those formats might evolve as you add engine features. As they evolve, you might find it necessary to keep certain programs compatible with previously saved files. No matter what format, you’ll ultimately need to serialize it in C++.

There are countless ways to implement serialization in C++. One fairly obvious way is to add load and save functions to the C++ classes you want to serialize. You can achieve backward compatibility by storing a version number in the file header, then passing this number into every load function. This works, although the code can become cumbersome to maintain.

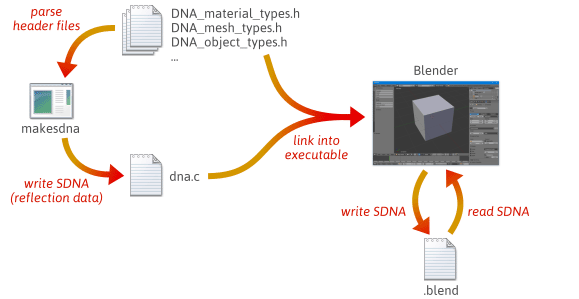

It’s possible to write more flexible, less error-prone serialization code by taking advantage of reflection – specifically, by creating runtime data that describes the layout of your C++ types. For a quick idea of how reflection can help with serialization, take a look at how Blender, an open source project, does it.

Like Blender, many game engines – and their associated tools – generate and use their own reflection data. There are many ways to do it: You can parse your own C/C++ source code to extract type information, as Blender does. You can create a separate data description language, and write a tool to generate C++ type definitions and reflection data from this language. You can use preprocessor macros and C++ templates to generate reflection data at runtime. And once you have reflection data available, there are countless ways to write a generic serializer on top of it.

Clearly, I’m omitting a lot of detail. In this post, I only want to show that there are many different ways to serialize data, some of which are very complex. Programmers just don’t discuss serialization as much as other engine systems, even though most other systems rely on it. For example, out of the 96 programming talks given at GDC 2017, I counted 31 talks about graphics, 11 about online, 10 about tools, 4 about AI, 3 about physics, 2 about audio – but only one that touched directly on serialization.

At a minimum, try to have an idea how complex your needs will be. If you’re making a tiny game like Flappy Bird, with only a few assets, you probably don’t need to think too hard about serialization. You can probably load textures directly from PNG and it’ll be fine. If you need a compact binary format with backward compatibility, but don’t want to develop your own, take a look at third-party libraries such as Cereal or Boost.Serialization. I don’t think Google Protocol Buffers are ideal for serializing game assets, but they’re worth studying nonetheless.

Writing a game engine – even a small one – is a big undertaking. There’s a lot more I could say about it, but for a post of this length, that’s honestly the most helpful advice I can think to give: Work iteratively, resist the urge to unify code a little bit, and know that serialization is a big subject so you can choose an appropriate strategy. In my experience, each of those things can become a stumbling block if ignored.

I love comparing notes on this stuff, so I’d be really interested to hear from other developers. If you’ve written an engine, did your experience lead you to any of the same conclusions? And if you haven’t written one, or are just thinking about it, I’m interested in your thoughts too. What do you consider a good resource to learn from? What parts still seem mysterious to you? Feel free to leave a comment below or hit me up on Twitter!

Check out Plywood, a cross-platform, open source C++ framework:

How to make your own game engine (and why)

(this article is reposted from my Medium blog)

So you’re thinking about making your own game engine. Great! There’s lots of reasons to want to make one yourself instead of using a commercial one like Unity or Unreal. In this post I will go over why you might want to, what systems are needed in a game engine, and how you should approach development of it. I won’t be going into any deep technical details here, this is about why and how to develop a game engine, not a tutorial for how to write the code.

Why?

Lets start with the absolute first question you should be asking yourself if you want to make your own game engine: Why?

Here’s a few good reasons why you might want to:

Also, you should absolutely consider your own experience and goals when weighing all of this. If you don’t have a lot of experience making games, you will have a much harder time making an engine (and you should definitely go get some game making experience before trying to make an engine anyway). If you want to do 3D, you will have a much harder time than just doing 2D.

These aren’t the only reasons why you’d want to make your own game engine. There’s a ton of advantages (and disadvantages) to it, and whether or not the pros outweigh the cons depends a whole lot on how much experience you have with both game dev in general and lower level coding. Like, it’s nice to just have your own tech, and its nice to not have to constantly google for tutorials that might be outdated for how to do something in your engine. It’s nice to be able to actually debug the internals of your game if something goes wrong. But it can also suck if you made a couple of bad design choices and everything falls apart entirely, and there’s no resources online to help you. You have full control and full responsibility, and all the pros and cons that come with that.

What?

Before we get into how to make your own game engine, lets take a step back and define what a game engine actually is, and the types of problems a game engine is supposed to solve.

A game engine is the framework upon which you make a game. It provides you a foundation on which to build on top of, and all the building blocks and lego pieces you need to assemble a game out of. It provides a boundary between “game logic” and “boring technical stuff” so that your game logic code (the stuff that actually describes what your game is, how it controls, the interactions between objects, and the rules), doesn’t need to actually care about stuff like how to send a triangle to the graphics card.

There’s actually a lot of variance in how much game engines actually do for you. Some of them are barely more than just a framework for displaying graphics, doing very little for you beyond that (Flash, Pico-8). Some of them are basically an entire game by themselves, or at least hyper-specialized for a specific genre, putting a ton of common game logic in the engine itself (RPGMaker, Ren’Py). And everything in-between.

Game engines themselves also tend to be built on top of even lower level frameworks like SDL and OpenGL, and include many special purpose libraries for things like audio, physics, math, and whatever else is out there that you find useful. Making a custom game engine does not mean writing every little piece of it yourself, especially something as standard and useful as SDL. Assembling the right set of existing libraries for your use case is part of making an engine as well, and there do exist libraries out there for nearly all of the systems you could want in your engine.

Anyway with that in mind, lets talk a bit about what I consider the most basic feature set you need for your game engine. The bare essentials. The minimum that you need before you can start making a game.

That is the basic set of systems that you’d need to have what I consider a game engine. Other systems like Collision and Physics and Serialization and Animation and UI and whatnot are actually optional. Most engines have them because they’re common enough that its worth including, but you don’t need those to make a game. You can get away with simple collision checks in your math utility library, and just let game logic do that all manually. You can do basic gravity and acceleration without a physics engine like Box2D or Bullet. And full serialization can often be huge overkill if all you need to do is save which checkpoint you spawn at.

If you’re writing your own engine, you will necessarily have less systems and features in it than the big general purpose commercial ones have. That should be the goal! Unity and Unreal are bloated monoliths, any individual game is only using a small slice of what they have to offer. Add only what you need, for your specific use case, and focus on making what’s important to you and your game extra good.

I very strongly recommend becoming familiar with how a bunch of different game engines work before starting out making your own. Learn what kinds of paradigms and structures they use, what’s cool about them and what’s annoying about them. Make a small game in a bunch of different engines if you can, just to obtain that knowledge.

How?

Ok so you’ve weighed the whys and explored the whats, and decided that you want to make your own game engine. How do you go about doing this?

I’ll get straight to the point: Make a game at the same time as you’re making the engine. This is an unbreakable rule. The only unbreakable rule. Get the basics in as fast as you possibly can and then immediately start making a game on top of it. An engine is nothing without a game.

You need to do this, because the features of an engine should be informed by the needs of the games made in it. You will not understand how to architect a good animation system if you don’t have a game that needs complicated animation flow. You will not know what your performance bottlenecks are if you don’t have a game. Do you need some kind of tree based world structure that will avoid updating or rendering objects that are too far away from the camera? I don’t know, and you don’t know either, until you have a large level that runs like crap. Even then, updating the objects might not be the actual bottleneck and you wont know until you profile it.

I’m not going deep into implementation details for these systems because there’s just way too many ways to do it that all work just fine for different purposes. There is no “best way to do rendering” or “best way to do game object management”. It all depends on your game. Start with the basics and expand them as you find need to.

For programming languages, use what you’re comfortable with. Making an engine is a big involved task, if you also try to learn C++ at the same time as trying to learn how to make a game engine you’re just doubling the difficulty of learning either of those tasks. C# is perfectly fine for making a game engine. Slower than C++, but often not slow enough to matter. Something really slow like python might be a bit of a stretch if your game has a lot of moving parts… but for some kinds of games it’s still fine. Use what you’re comfortable with.

Also, you will never get this right on your first try. My first game with a custom engine was Closure, and it was an absolute mess (despite, kind of hilariously, being nominated for a Technical Excellence award at the 2010 IGF). One big update function and one big render function handled basically the entirety of the game. Adding new kinds of game objects was extremely annoying and required adding code in a ton of different places, and working with some janky ass custom editors for animations, so we ended up with only about a dozen different kinds of interactive objects in the end, though some of them had some variants (bool toggles) that changed their behavior significantly because it was easier to add variants than it was to add new objects. The spotlights, mirrors, and turret are all the same object!

But you learn from this experience. Closure’s engine was a mess, but it still shipped in that state, and it was “good enough” that I could run it on the PS3 without that much hassle. It was tempting to rewrite the engine at points, but rather than do that (which would have only served to delay the game), I just kept notes of all the things about it that sucked so I could do things better the next time. Especially things that got in the way of actually making the game. I did the same thing with The End is Nigh. Its engine (while much, MUCH better than Closure’s) still had a bunch of issues with it that I just grit my teeth and dealt with during dev. As soon as the game came out, I immediately started updating the engine for use in our next project, fixing all the annoyances with it and adding in the new features we needed.

It’s an iterative process through and through. You learn, make a game, iterate and repeat. Over and over until eventually your engine is good.

Hopefully you should understand why I didn’t bother giving any technical details for how to implement all those individual systems. It just depends way too much on your specific use cases, and there’s hundreds of different, completely valid ways, to approach each of them. Figuring out what works for you IS what making your own game engine is about, and that’s the mindset you should be in when writing your own stuff.

Who?

Anyway that’s about all I wanted to cover in this post, hopefully you’re either motivated to write your own game engine now, or scared away from the thought of it entirely. Both are good outcomes! If you have any actual questions about technical details or opinions on game dev or game engine development, feel free to ask me about it on Twitter (publicly) and I’ll do my best to respond. Thanks for reading!

How to Make Your Own C++ Game Engine

(This blog post was originally posted on pikuma.com)

So you want to learn more about game engines and write one yourself? That’s awesome! To help you on your journey, here are some recommendations of C++ libraries and dependencies that will help you hit the ground running.

Game development has always been a great helper to get my students motivated to learn more about more advanced computer science topics.

One of my tutors, Dr. Sepi, once said:

«Some people think games are kid’s stuff, but gamedev is one of the few areas that uses almost every item of the standard CS curriculum.»- Dr. Sepideh Chakaveh

As always, she is absolutely right! If we expose what is hidden under the development stack of any modern game, we’ll see that it touches many concepts that are familiar to any computer science student.

Depending on the nature of your game, you might need to dive even deeper into more specialized areas, like distributed systems or human-computer interaction. Game development is serious business and it can be a powerful tool to learn serious CS concepts.

This article will go over some of the fundamental building blocks that are required to create a simple game engine with C++. I’ll explain the main elements that are required in a game engine, and give some personal recommendations on how I like to approach writing one from scratch.

That being said, this will not be a coding tutorial. I won’t go into too much technical detail or explain how all these elements are glued together via code. If you are looking for a comprehensive video book on how to write a C++ game engine, this is a great starting point: Create a 2D Game Engine with C++ & Lua.

What is a Game Engine?

If you are reading this, chances are you already have a good idea of what a game engine is, and possibly even tried to use one yourself. But just so we are all on the same page, let’s quickly review what game engines are and what they help us achieve.

A game engine is a set of software tools that optimizes the development of video games. These engines can be small and minimalist, providing just a game loop and a couple of rendering functions, or be large and comprehensive, similar to IDE-like applications where developers can script, debug, customize level logic, AI, design, publish, collaborate, and ultimately build a game from start to finish without the need to ever leave the engine.

Game engines and game frameworks usually expose an API to the user. This API allows the programmer to call engine functions and perform hard tasks as if they were black boxes.

To really understand how this API thing works, let’s put it into context. For example, it is not rare for a game engine API to expose a function called «IsColliding()» that developers can invoke to check if two game objects are colliding or not. There is no need for the programmer to know how this function is implemented or what is the algorithm required to correctly determine if two shapes are overlapping. As far as we are concerned, the IsColliding function is a black box that does some magic and correctly returns true or false if those objects are colliding with each other or not. This is an example of a function that most game engines expose to their users.

Besides a programming API, another big responsibility of a game engine is hardware abstraction. For example, 3D engines are usually built upon a dedicated graphics API like OpenGL, Vulkan, or Direct3D. These APIs provide a software abstraction for the Graphics Processing Unit (GPU).

Speaking of hardware abstraction, there are also low-level libraries (like DirectX, OpenAL, and SDL) that provide abstraction & multi-platform access to many other hardware elements. These libraries help us access and handle keyboard events, mouse movement, network connection, and even audio.

The Rise of Game Engines

In the early years of the game industry, games were built using a custom rendering engine and the code was developed to squeeze as much performance as possible from slower machines. Every CPU cycle was crucial, so code reuse or generic functions that worked for multiple scenarios was not a luxury that developers could afford.

As games and development teams grew in both size and complexity, most studios ended up reusing functions and subroutines between their games. Studios developed in-house engines that were basically a collection of internal files and libraries that dealt with low-level tasks. These functions allowed other members of the development team to focus on high-level details like gameplay, map creation, and level customization.

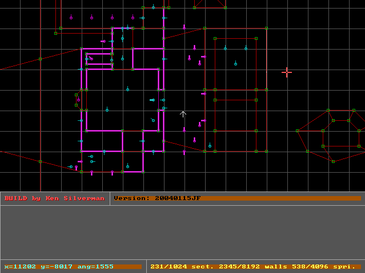

Some popular classic engines are id Tech, Build, and AGI. These engines were created to aid the development of specific games, and they allowed other members of the team to rapidly develop new levels, add custom assets, and customize maps on the fly. These custom engines were also used to mod or create expansion packs for their original games.

Id Software developed id Tech. id Tech is a collection of different engines where each iteration is associated with a different game. It is common to hear developers describe id Tech 0 as «the Wolfenstein3D engine», id Tech 1 as «the Doom engine», and id Tech 2 as «the Quake engine.»

Build is another example of engine that helped shape the history of 90’s games. It was created by Ken Silverman to help customize first-person shooters. Similar to what happened to id Tech, Build evolved with time and its different versions helped programmers develop games such as Duke Nukem 3D, Shadow Warrior, and Blood. These are arguably the most popular titles created using the Build engine, and are often referred as «The Big Three.»

Yet another example of game engine from the 90s was the «Script Creation Utility for Manic Mansion» (SCUMM). SCUMM was an engine developed at LucasArts, and it is the base of many classic Point-and-Click games like Monkey Island and Full Throttle.

As machines evolved and became more powerful, so did game engines. Modern engines are packed with feature-rich tools that require fast processor speeds, ridiculous amount of memory, and dedicated graphics cards.

With power to spare, modern engines trade machine cycles for more abstraction. This trade-off means we can view modern game engines as general-purpose tools to create complex games at low cost and short development times.

Why Make a Game Engine?

This is a very common question, and different game programmers will have their own take on this topic depending on the nature of the game being developed, their business needs, and other driving forces being considered.

There are many free, powerful, and professional commercial engines that developers can use to create and deploy their own games. With so many game engines to choose from, why would anyone bother to make a game engine from the ground up?

I wrote a blog post called «Should I Make a Game Engine or Use an Existing One?» explaining some of the reasons programmers might decide to make a game engine/framework from scratch. In my opinion, the top reasons are:

Learning opportunity: a low-level understanding of how game engines work under the hood can make you grow as a developer.

Workflow control: you’ll have more control over special aspects of your game and adjust the solution to fit your workflow needs.

Customization: you’ll be able to tailor a solution for a unique game requirement.

Minimalism: a smaller codebase can reduce the overhead that comes with bigger game engines.

Innovation: you might need to implement something completely new or target unorthodox hardware that no other engine supports.

I will continue our discussion assuming you are interested in the educational appeal of game engines. Creating a small game engine from scratch is something I strongly recommend to all my CS students.

Considerations When Writing a Game Engine

So, after this quick talk about the motivations of using and developing game engines, let’s go ahead and discuss some of the components of game engines and learn how we can go about writing one ourselves.

1. Choosing a Programming Language

One of the first decisions we face is choosing the programming language we’ll use to develop the core engine code. I have seen engines being developed in raw assembly, C, C++, and even high-level languages like C#, Java, Lua, and even JavaScript!

One of the most popular languages for writing game engines is C++. The C++ programming language combines speed with the ability to use object-oriented programming (OOP) and other programming paradigms that help developers organize and design large software projects.

Since performance is usually a great deal when we develop games, C++ has the advantage of being a compiled language. A compiled language means that the final executables will run natively on the processor of the target machine. There are also many dedicated C++ libraries and development kits for most modern consoles, like PlayStation or Xbox.

Speaking of performance, I personally don’t recommend languages that use virtual machines, bytecode, or any other intermediary layer. Besides C++, some modern alternatives that are suited for writing core game engine code are Rust, Odin, and Zig.

For the remainder of this article, my recommendations will assume the reader wants to build a simple game engine using the C++ programming language.

2. Hardware Access

In older operating systems, like the MS-DOS, we could usually poke memory addresses and access special locations that were mapped to different hardware components. For example, all I had to do to «paint» a pixel with a certain color was to load a special memory address with the number that represented the correct color of my VGA palette, and the display driver translated that change to the physical pixel into the CRT monitor.

As operating systems evolved, they became responsible for protecting the hardware from the programmer. Modern operating systems will not allow the code to modify memory locations that are outside the allowed addresses given to our process by the OS.

For example, if you are using Windows, macOS, Linux, or *BSD, you’ll need to ask the OS for the correct permissions to draw and paint pixels on the screen or talk to any other hardware component. Even the simple task of opening a window on the OS desktop is something that must be performed via the operating system API.

Therefore, running a process, opening a window, rendering graphics on the screen, paining pixels inside that window, and even reading input events from the keyboard are all OS-specific tasks.

One very popular library that helps with multi-platform hardware abstraction is SDL. I personally like using SDL when I teach gamedev classes because with SDL I don’t need to create one version of my code for Windows, another version for macOS, and another one for Linux students. SDL works as a bridge not just for different operating systems, but also different CPU architectures (Intel, ARM, Apple M1, etc.). The SDL library abstracts the low-level hardware access and «translates» our code to work correctly on these different platforms.

Here is a minimal snippet of code that uses SDL to open a window on the operating system. I’m not handling errors for the sake of simplicity, but the code below will be the same for Windows, macOS, Linux, BSD, and even RaspberryPi.

But SDL is just one example of library that we can use to achieve this multi-platform hardware access. SDL is a popular choice for 2D games and to port existing code to different platforms and consoles. Another popular option of multi-platform library that is used mostly with 3D games and 3D engines is GLFW. The GLFW library communicates very well with accelerated 3D APIs like OpenGL and Vulkan.

3. Game Loop

Once we have our OS window open, we need to create a controlled game loop.

Put simply, we usually want our games to run at 60 frames per second. The framerate might be different depending on the game, but to put things into perspective, movies shot on film run at a 24 FPS rate (24 images flash past your eyes every single second).

A game loop runs continuously during gameplay, and at each pass of the loop, our engine needs to run some important tasks. A traditional game loop must:

Process Input events without blocking

Update all game objects and their properties for the current frame

Render all game objects and other important information on the screen

That’s a cute while-loop. Are we done? Absolutely not!

A raw C++ loop is not good enough for us. A game loop must have some sort of relationship with real-world time. After all, the enemies of the game should move at the same speed on a any machine, regardless of their CPU clock speed.

Controlling this framerate and setting it to a fixed number of FPS is actually a very interesting problem. It usually requires us to keep track of time between frames and perform some reasonable calculations to make sure our games run smoothly at a framerate of at least 30 FPS.

4. User Input

I cannot imagine a game that does not read some sort of input event from the user. These can come from a keyboard, a mouse, a gamepad, or a VR set. Therefore, we must process and handle different input events inside our game loop.

To process user input, we must request access to hardware events, and this must be performed via the operating system API. The good news is that we can use a multi-platform hardware abstraction library (SDL, GLFW, SFML, etc.) to handle user input for us.

If we are using SDL, we can poll events and proceed to handle them accordingly with a few lines of code.

Once again, if we are using a cross-platform library like SDL to handle input, we don’t have to worry too much about OS-specific implementation. Our C++ code should be the same regardless of the platform we are targeting.

After we have a working game loop and a way of handling user input, it’s time for us to start thinking about organizing our game objects in memory.

5. Representing Game Objects in Memory

When we are designing a game engine, we need to setup data structures to store and access the objects of our game.

There are several techniques that programmers use when architecturing a game engine. Some engines might use a simple object-oriented approach with classes and inheritance, while other engines might organize their objects as entities and components.

If one of your goals is to learn more about algorithms and data structures, my recommendation is for you to try implementing these data structures yourself. If you’re using C++, one option is to use the STL (standard template library) and take advantage of the many data structures that come with it (vectors, lists, queues, stacks, maps, sets, etc.). The C++ STL relies heavily on templates, so this can be a good opportunity to practice working with templates and see them in action in a real project.

As you start reading more about game engine architecture, you’ll see that one of the most popular design patterns used by games is based on entities and components. An entity-component design organizes the objects of our game scene as entities (what Unity calls «game objects» and Unreal calls «actors»), and components (the data that we can add or attach to our entities).

To understand how entities and components work together, think of a simple game scene. The entities will be our main player, the enemies, the floor, the projectiles, and the components will be the important blocks of data that we «attach» to our entities, like position, velocity, rigid body collider, etc.

Some examples of components that we can choose to attach to our entities are:

Position component: Keeps track of the x-y position coordinates of our entity in the world (or x-y-z in 3D).

Velocity component: Keeps track of how fast the entity is moving in the x-y axis (or x-y-z in 3D).

Sprite component: It usually stores the PNG image that we should render for a certain entity.

Animation component: Keeps track of the entity’s animation speed, and how the animation frames change over time.

Collider component: This is usually related to physics characteristics of a rigid body, and defines the colliding shape of an entity (bounding box, bounding circle, mesh collider, etc.).

Health component: Stores the current health value of an entity. This is usually just a number or in some cases a percentage value (a health bar, for example).

Script component: Sometimes we can have a script component attached to our entity, which might be an external script file (Lua, Python, etc) that our engines must interpret and execute behind the scenes.

This is a very popular way of representing game objects and important game data. We have entities, and we «plug» different components to our entities.

There are many books and articles that explore how we should go about implementing an entity-component design, as well as what data structures we should use in this implementation. The data structures we use and how we access them have a direct impact on our game’s performance, and you’ll hear developers mention things like Data-Oriented Design, Entity-Component-System (ECS), data locality, and many other ideas that have everything to do with how our game data is stored in memory and how we can access this data efficiently.

Representing and accessing game objects in memory can be a complex topic. In my opinion, you can either code a simple entity-component implementation manually, or you can simply use an existing third-party ECS library.

There are some popular options of ready-to-use ECS libraries that we can include in our C++ project and start creating entities and attaching components without having to worry about how they are implemented under the hood. Some examples of C++ ECS libraries are EnTT and Flecs.

I personally recommend students that are serious about programming to try implementing a very simple ECS manually at least once. Even if your implementation is not perfect, coding an ECS system from scratch will force you to think about the underlying data structures and consider their performance.

Now, serious talk! Once you’re done with your custom ad-hoc ECS implementation, I would encourage you to just use some of the popular third-party ECS libraries (EnTT, Flecs, etc.). These are professional libraries that have been developed and tested by the industry for several years. They are probably a lot better than anything we could come up from scratch ourselves.

In summary, a professional ECS is difficult to implement from scratch. It is valid as an academic exercise, but once you’re done with your small learning project, just pick a well-tested third-party ECS library and add it to your game engine code.

6. Rendering

Alright, it looks like our game engine is slowly growing in complexity. Now that we have discussed about ways of storing and accessing game objects in memory, we need to probably talk about how we render objects on the screen.

The first step is to consider the nature of the games that we will be creating with our engine. Are we creating a game engine to develop only 2D games? If that’s the case, we need to think about rendering sprites, textures, managing layers, and probably take advantage of graphics card acceleration. The good news is that 2D games are usually simpler than 3D ones, and 2D math is considerably easier than 3D math.

If your goal is to develop a 2D engine, you can use SDL to help with multi-platform rendering. SDL abstracts accelerated GPU hardware, can decode and display PNG images, draw sprites, and render textures inside our game window.

Now, if your goal is to develop a 3D engine, then we’ll need to define how we send some extra 3D information (vertices, textures, shaders, etc) to the GPU. You’ll probably want to use a software abstraction to the graphics hardware, and the most popular options are OpenGL, Direct3D, Vulkan, and Metal. The decision of which API to use might depend on your target platform. For example, Direct3D will power Microsoft apps, while Metal will work solely with Apple products.

3D applications work by processing 3D data through a graphics pipeline. This pipeline will dictate how your engine must send graphics information to the GPU (vertices, texture coordinates, normals, etc.). The graphics API and the pipeline will also dictate how we should write programmable shaders to transform and modify vertices and pixels of our 3D scene.

7. Physics

When we add entities to our engine, we probably also want them to move, rotate, and bounce around our scene. This subsystem of a game engine is the physics simulation. This can either be created manually, or imported from an existing ready-to-use physics engine.

Here, we also need to consider what type of physics we want to simulate. 2D physics is usually simpler than 3D, but the underlying parts of a physics simulation are very similar to both 2D and 3D engines.

If you simply want to include a physics library to your project, there are several great options to choose from.

For 2D physics, I recommend looking at Box2D and Chipmunk2D. For professional and stable 3D physics simulation, some good names are libraries like PhysX and Bullet. Using a third-party physics engine is always a good call if physics stability and development speed are crucial for your project.

As an educator, I strongly believe every programmer should learn how to code a simple physics engine at least once in their career. Once again, you don’t need to write a perfect physics simulation, but focus on making sure objects can accelerate correctly and that different types of forces can be applied to your game objects. And once movement is done, you can also think of implementing some simple collision detection and collision resolution.

If you want to learn more about physics engines, there are some good books and online resources that you can use. For 2D rigid-body physics, you can look at the Box2D source code and the slides from Erin Catto. But if you are looking for a comprehensive course about game physics, Creating a 2D Physics Engine from Scratch is probably a good place to start.

If you want to learn about 3D physics and how to implement a robust physics simulation, another great resource is the book «Game Physics» by David Eberly.

When we think of modern game engines like Unity or Unreal, we think of complex user interfaces with many panels, sliders, drag-and-drop options, and other pretty UI elements that help users customize our game scene. The UI allows the developer to add and remove entities, change component values on-the-fly, and easily modify game variables.

Just to be clear, we are talking about game engine UI for tooling, and not the user interface that we show to the users of your game (like dialog screens and menus).

Keep in mind that game engines do not necessarily need to have an editor embedded to them, but since game engines are usually used to increase productivity, having a friendly user interface will help you and other team members to rapidly customize levels and other aspects of the game scene.

Developing a UI framework from the ground up is probably one of the most annoying tasks that a beginner programmer can attempt to add to a game engine. You’ll have to create buttons, panels, dialog boxes, sliders, radio buttons, manage colors, and you’ll also need to correctly handle the events of that UI and always persist its state. Not fun! Adding UI tools to your engine will make your application increase in complexity and add an incredible amount of noise to your source code.

If your goal is to create UI tools for your engine, my recommendation is to use an existing third-party UI library. A quick Google search will show you that the most popular options are Dear ImGui, Qt, and Nuklear.

Dear ImGui is one of my favorites, as it allows us to quickly set up user interfaces for engine tooling. The ImGui project uses a design pattern called «immediate mode UI«, and it is widely used with game engines because it communicates well with 3D applications by taking advantage of accelerated GPU rendering.

In summary, if you want to add UI tools to your game engine, my suggestion is to simply use Dear ImGui.

9. Scripting

As our game engine grows, one popular option is to enable level customization using a simple scripting language.

The idea is simple; we embed a scripting language to our native C++ application, and this simpler scripting language can be used by non-professional programmers to script entity behavior, AI logic, animation, and other important aspects of our game.

Some of the popular scripting languages for games are Lua, Wren, C#, Python, and JavaScript. All these languages operate at a considerably higher level than our native C++ code. Whoever is scripting game behavior using the scripting language does not need to worry about things like memory management or other low-level details of how the core engine works. All they need to do is script the levels and our engine knows how to interpret the scripts and perform the hard tasks behind the scenes.

My favorite scripting language is Lua. Lua is small, fast, and extremely easy to integrate with C and C++ native code. Also, if I’m working with Lua and «modern» C++, I like to use a wrapper library called Sol. The Sol library helps me hit the ground running with Lua and offers many helper functions to improve the traditional Lua C-API.

If we enable scripting, we are almost reaching a point where we can start talking about more advanced topics in our game engine. Scripting helps us define AI logic, customize animation frames and movement, and other game behavior that does not need to live inside our native C++ code and can easily be managed via external scripts.

10. Audio

Another element that you might consider adding support to a game engine is audio.

It is no surprise that, once again, if we want to poke audio values and emit sound, we need to access audio devices via the OS. And once again, since we don’t usually want to write OS-specific code, I am going to recommend using a multi-platform library that abstracts audio hardware access.

Multi-platform libraries like SDL have extensions that can help your engine handle things like music and sound effects.

But, serious talk now! I would strongly suggest tackling audio only after you have the other parts of your engine already working together. Emitting sound files can be easy to achieve, but once we start dealing with audio synchronization, linking audio with animations, events, and other game elements, things can become messy.

If you are really doing things manually, audio can be tricky because of multi-threading management. It can be done, but if your goal is to write a simple game engine, this is one part that I like to delegate to a specialized library

Some good libraries and tools for audio that you can consider integrating with your game engine are SDL_Mixer, SoLoud, and FMOD.

11. Artificial Intelligence

The final subsystem I’ll include in our discussion is AI. We could achieve AI via scripting, which means we could delegate the AI logic to level designers to script. Another option would be to have a proper AI system embedded in our game engine core native code.

In games, AI is used to generate responsive, adaptive, or intelligent-like behavior to game objects. Most AI logic is added to non-player characters (NPCs, enemies) to simulate human-like intelligence.

Enemies are a popular example of AI application in games. Game engines can create abstractions over path-finding algorithms or interesting human-like behavior when enemies chase objects on a map.

A comprehensive book about the theory and implementation of artificial intelligence for games is called AI for Games by Ian Millington.

Don’t Try to Do Everything At Once

Alright! We have just discussed some important ideas that you can consider adding to a simple C++ game engine. But before we start gluing all these pieces together, I just want to mention something super important.

One of the hardest parts of working on a game engine is that most developers will not set clear boundaries, and there is no sense of «end line.» In other words, programmers will start a game engine project, render objects, add entities, add components, and it’s all downhill after that. If they don’t define boundaries, it’s easy to just start adding more and more features and lose track of the big picture. If that happens, there is a big chance that the game engine will never see the light of day.

Besides lacking boundaries, it is easy to get overwhelmed as we see the code grow in front of our eyes at lightning speed. A game engine project has the potential of quickly growing in complexity and in a few weeks, your C++ project can have several dependencies, require a complex build system, and the overall readability of your code drops as more features are added to the engine

One of my first suggestions here is to always write your game engine while you’re writing an actual game. Start and finish the first iteration of your game with an actual game in mind. This will help you to set limits and define a clear path for what you needs to be completed. Try your best to stick to it and not get tempted to change the requirements along the way.

Take Your time and Focus on the Basics

If you’re creating your own game engine as a learning exercise, enjoy the small victories!

Most student gets super excited at the beginning of the project, and as days go by the anxiety starts to appear. If we are creating a game engine from scratch, especially when using a complex language like C++, it is easy to get overwhelmed and lose some momentum.

I want to encourage you to fight that feeling of «running against time.» Take a deep breath and enjoy the small wins. For example, when you learn how to successfully display a PNG texture on the screen, savor that moment and make sure you understand what you did. If you managed to successfully detect the collision between two bodies, enjoy that moment and reflect on the knowledge that you just gained.

Focus on the fundamentals and own that knowledge. It doesn’t matter how small or simple a concept is, own it. Everything else is ego.

Preshing on Programming

Preshing on Programming