It features some kind of story of plot which is made using drawings

It features some kind of story of plot which is made using drawings

Plot structure

Plot is often designed with a narrative structure, storyline or story arc that includes exposition, conflict, rising action and climax, followed by a falling action and resolution.

Exposition: orients the reader to the setting of the story (time and place) and introduces the characters. Exposition is a literary technique concerned with introducing characters and setting. These elements may be largely presented at the beginning of the story, or may occur as a sort of incidental description throughout. Exposition may be handled in a variety of ways — perhaps a character or a set of characters explain the elements of the plot through dialogue or thought, media such as newspaper clippings, and diaries.

Conflict: the primary obstacle that prevents the protagonist from reaching his/her goal. Conflict is the «problem» in a story which triggers the action. There are five basic types of conflict: Person vs. Person: One character in a story has a problem with one or more of the other characters; Person vs. Society: A character has a conflict or problem with society; Person vs. Himself or Herself: A character struggles inside and has trouble deciding what to do; Person vs. Nature: A character has a problem with some element of nature, (e.g., a snowstorm, an avalanche, the bitter cold); Person vs. Fate: A character has to battle what seems to be an uncontrollable problem.

Remember these two things when writing conflict:

· Conflict between the two main characters generates emotional tension.

· Characters are driven by conflict — and they, in turn, will drive the story.

What is emotional conflict?

There are two types of conflict that will progress a romance: internal and external.

Internal conflict can come about by two routes:

· Character: a conflict can grow out of the hero or heroine’s fundamental personality, and will include how their lives and backgrounds have shaped them, what their motivations and aspirations are. For example, your hero is now an international billionaire who is ruthless in business and love, having clawed his way out of an orphaned background in the slums of Naples.

· Emotional conflict: this exists within the central relationship. For instance, an unexpected pregnancy or an arranged marriage can upset two colliding worlds!

External conflict comes from misunderstandings and circumstances. Example: the hero has arrived to take over the heroine’s father’s ailing company and uses her perilous position to blackmail her into a relationship. Or it can come about because of another secondary character’s influence. Example: the hero’s father is dying and wants to see his son married.

Rising action: the complications that occur within the story, prolonging and developing the central conflict. Rising Action is the central part of a story during which various problems arise, leading up to the climax.

Climax: the point of greatest tension in a story; the point of no return. The climax usually features the most conflict and struggle, and usually reveals any secrets or missing points in the story. Alternatively, an anti-climax may occur, in which an expectedly difficult event is revealed to be incredibly easy or of paltry importance. Critics may also label the falling action as an anti-climax. The climax isn’t always the most important scene in a story. In many stories, it is the last sentence, with no successive falling action or resolution.

Falling action: the result of the conflict is revealed in the falling action. The falling action is the part of a story following the climax. This part of the story shows the result of the climax, and its effects on the characters, setting, and proceeding events. Critics may label a story with falling action as the anti-climax if they feel that the falling action takes away from the power of the climax.

Denouement: the resolution of the story. The denouement ties up any loose ends in the story. Etymologically, the French word dénouement is derived from the Old French word denoer, «to untie», and from nodus, Latin for «knot». In fiction, a dénouement consists of a series of events that follow the climax, and thus serves as the conclusion of the story. Conflicts are resolved, creating normality for the characters and a sense of catharsis, or release of tension and anxiety, for the reader. Simply put, dénouement is the unraveling or untying of the complexities of a plot. Be aware that not all stories have a resolution.

Structure of the Plot:

I. Introduction: Several things may be introduced at the beginning of the story.

A.Setting: Where and when the story takes place

B.Protagonist: The main character of the story; who the story is about; this character sets the action in motion.

C.Mood: The emotional feeling the reader gets from the setting and character description; the atmosphere.

D.Tone: The attitude of the speaker or narrator.

II. Rising Action: This essentially the point where the protagonist meets the antagonist.

A.Conflict: One force meets an opposing force.

1. Person vs. Person (External Conflict)

2. Person vs. Nature (External Conflict)

3. Person vs. Himself or Herself (Internal Conflict)

4. Person vs. Society (External Conflict)

5. Person vs. Fate, Destiny, God (External Conflict)

B. Antagonist: The character or force which opposes the protagonist.

III. Climax: The point at which the reader can see who will inevitable win the conflict. This can often not be seen until the story is over and the reader looks back on the plot. The climax is not the most exciting part of the story! Some stories do not have exciting parts.

IV. Denouement: This is French for “unknotting” and is essentially the wrapping up of all the loose details of the plot in order to satisfy the reader or audience.

These are the four classic parts of a plot. Depending upon the artist, a story may not have all the parts. Many stories are without a denouement. A story like “The Lady or the Tiger” by Frank Stockton does not have a climax.

You may find that many typical television shows and popular novels follow this particular structure. Most short stories will have these plot elements in them. But they may not follow the typical plot structure outlined here. Writers vary structure depending on the needs of the story. The elements of plot structure may be juxtaposed in atypical ways or typical plot elements are missing or intimated rather than overtly stated.

In comparison with plot composition is a much wider notion. It comprises plot and extra-plot elements (descriptions, meditations, references). Composition is the way of text organization, forming up (shaping) its structure.

Literary composition is the organization — specifically, the arrangement and interrelation — of the diverse components of a written work. It includes the arrangement and correlation of characters (composition as a system of characters), events and actions (composition of the plot), inserted tales and lyrical digressions (composition of elements outside of the plot), methods of narration (narrative composition proper), and details of setting, behavior, and emotions (composition of details).

There are many devices and methods of composition. Events, commonplace objects, facts, and details that appear in disparate parts of the text may prove to be of artistic significance when taken together. A major aspect of composition is succession, or the order in which components appear in the text. Succession is the temporal organization of a literary work, or the unveiling and unfolding of the artistic content. Composition also includes the mutual correlation of the various facets of literary form (such structural concepts as planes, layers, and levels). Many contemporary theorists use the word “structure” as a synonym for composition.

Composition completes the complex unity and wholeness of a work, consummating an artistic form that already is rich in content. Composition has the task of making sure that nothing goes astray but becomes part of a whole, fulfilling the aims of the author; its aim is to arrange all the pieces in such a way that they come together in a complete expression of the idea.

Every work combines general methods of composition that are typical of a particular kind, genre, or tendency with individual methods peculiar to a particular writer or work. Examples of general methods of composition are thrice-repeated motifs in folk tales, recognition and aposiopesis in adventure stories, the rigid strophic form of the sonnet, and slow development in the epic and drama.

In the contemporary study of literature the use of the term “composition” is more limited. In this sense an individual segment of a text functions as an element of composition, in which a particular method of representation is used, such as ongoing narration, descriptive passages, characterization, dialogue, or lyric digression. The most basic elements of composition combine to form more complex components (complete portrait sketches, descriptions of emotional states, and recollections of conversations). In an epic or drama the scene is an even more important and independent component. In the epic it may consist of several forms of representation (description, narration, or monologue). A portrait, landscape, or interior may be included in the scene; however, throughout its entire course one perspective is maintained and a definite point of view is upheld (the author’s, a character’s, or an outside narrator’s). Each scene may be presented as seen solely through the eyes of a particular person. Thus, composition comprises the combination, interaction, and unity of the forms of narration and definite points of view.

Composition of poetry, particularly of lyrical verse, is unique. It is distinguished by strict proportionality and interaction of the rhythmical and metrical units (foot, line, and stanza), syntax and intonations, and the elements that directly convey meaning (themes, motifs, and images).

In 20th-century literature, composition has become especially important. This new importance was reflected in the emergence of the montage, which was initially introduced in motion pictures and later was used in theater and literature.

Match the genres with the descriptions.

a WESTERN 1 A film full of music and dance

2 A film in which unnatural and frightening things happens, such as

dead people coming to life, people turning to animals.

c THRILLER 3 An action-packed film about cowboys, horses and gunfights.

d COMEDY 4 A film about space travel or life in an imaginary future.

e HORROR 5 A film made by photographing, a set of drawings.

f CARTOONS 6 A film full of violence and crime.

g MUSICAL 7 An film with happy end.

2. What types of films do these people talk about? Use the names of genres instead of

1. – What do you think of the film?

– Oh, it was extremely good! I was kept in uncertainly up to the end. The story line was so

b) – It is a pretty good film. The story line is simple but touching.

– Yes, the plot is really very simple but … don’t need to be complicated and mysterious. Usually

they are naive but we like them for it.

2. – Do you like the film?

– Oh, yes. It was really good. I like films which are full of fights and adventures.

– Oh yes, you do. And this one was really stuffed with fights. I think there were too many of

– You simply don’t like … I guess.

3. Match different kinds of TV programmes with their descriptions.

1. documentary a) factual film about animals and plants

2. the news b) informal talk, usually with famous people

3. chat show c) the latest events in the world and in your country

4. soap opera d) non-fiction film based on real events

5. nature programme e) drama, usually about family life; often weekly

6. weather forecast f) advertisement

7. commercial g) information about temperature, wind, rain, sun and so

4. Write definitions for the following kinds of films using the phrases below.

has a serious story often has an exciting story

has cowboys in it about crime and police

makes you laugh has lots of exiting action

has a story about love is about police and detectives

is about space and the future

An adventure film has lots of exciting action.

A comedy ___________________________.

A drama ____________________________.

A thriller ____________________________.

A western ___________________________.

A romance __________________________.

A crime story ________________________.

A science fiction _____________________.

5. Cinema combines different arts. That’s why people of different professions

are involved in film making. Who are these people? Match the name of the

professions and what they do.

a) camera operator b) actor c) electrician

d) costume designer e) make-up artist

f) boom operator g) sound mixer h) director

i) stuntman/-woman j) editor

k) director of photography l) producer

1. has general control of the money for a film but he doesn’t direct the actors

2. fixes the lights and all other electrical equipment

3. is the boss and tells everybody what to do. He works very closely with the actors in particular

4. looks through the camera, and operates the equipment

5. decides the position of the camera, and everything to do with light, colour, quantity and direction

6. writes scripts for films, shows

7. holds the microphone

8. does all the dangerous things on the screen instead of actors

9. chooses the best bits of the shooting film, cuts film and puts the bits together

10. operates the microphones and gets very angry with people who makes noises during the filming

11. pretends to be another person and acts in a film

12. prepares costumes: dresses, suits for films

13. can make a new face for an actor

6. Here is a short review of the achievements of Australian cinematography.

Fill in the gaps in the story using the words from the box.

adventures The Piano shooted films prize

Crocodile Dandee dancers film industry

directors directed the government Hollywood

Australian film industry is as old as _____________. Australians make a lot of good __________. They

are proud of their ___________ and ____________ gives money to the film companies. Australian films are

known all over the world. There are some big international successes such as the ___________________ film,

about the ___________________ in Australia and Strictly Ballroom – a wonderful story about young

____________. ____________ which is ___________ by Jane Campion, won the main ___________ at the

Cannes Film Festival in 1993. one of the most famous Australian ___________ is Peter Weir. He

___________ Picnic at Hanging Rock. It is a story about a group of schoolgirls who disappeared after a picnic.

SAT / ACT Prep Online Guides and Tips

What Is the Plot of a Story? The 5 Parts of the Narrative

When we talk about stories, we tend to use the word «plot.» But what is plot exactly? How does it differ from a story, and what are the primary features that make up a well-written plot? We answer these questions here and show you real plot examples from literature. But first, let’s take a look at the basic plot definition.

What Is Plot? Definition and Overview

What is the plot of a story? The answer is pretty simple, actually.

Plot is the way an author creates and organizes a chain of events in a narrative. In short, plot is the foundation of a story. Some describe it as the «what» of a text (whereas the characters are the «who» and the theme is the «why»).

This is the basic plot definition. But what does plot do?

The plot must follow a logical, enticing format that draws the reader in. Plot differs from «story» in that it highlights a specific and purposeful cause-and-effect relationship between a sequence of major events in the narrative.

In Aspects of the Novel, famed British novelist E. M. Forster argues that instead of merely revealing random events that occur within a text (as «story» does), plot emphasizes causality between these events:

«We have defined a story as a narrative of events arranged in their time-sequence. A plot is also a narrative of events, the emphasis falling on causality. ‘The king died and then the queen died,’ is a story. ‘The king died, and then the queen died of grief’ is a plot. The time-sequence is preserved, but the sense of causality overshadows it.»

Authors typically develop their plots in ways that are most likely to pique the reader’s interest and keep them invested in the story. This is why many plots follow the same basic structure. So what is this structure exactly?

What Is Plot Structure?

All plots follow a logical organization with a beginning, middle, and end—but there’s a lot more to the basic plot structure than just this. Generally speaking, every plot has these five elements in this order:

#1: Exposition/Introduction

The first part of the plot establishes the main characters/protagonists and setting. We get to know who’s who, as well as when and where the story takes place. At this point, the reader is just getting to know the world of the story and what it’s going to be all about.

Here, we’re shown what normal looks like for the characters.

The primary conflict or tension around which the plot revolves is also usually introduced here in order to set up the course of events for the rest of the narrative. This tension could be the first meeting between two main characters (think Pride and Prejudice) or the start of a murder mystery, for example.

#2: Rising Action

In this part of the plot, the primary conflict is introduced (if it hasn’t been already) and is built upon to create tension both within the story and the reader, who should ideally be feeling more and more drawn to the text. The conflict may affect one character or multiple characters.

The author should have clearly communicated to the reader the stakes of this central conflict. In other words, what are the possible consequences? The benefits?

This is the part of the plot that sets the rest of the plot in motion. Excitement grows as tensions get higher and higher, ultimately leading to the climax of the story (see below).

For example, in Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, the rising action would be when we learn who Voldemort is and lots of bad things start happening, which the characters eventually realize are all connected to Voldemort.

#3: Climax/Turning Point

Arguably the most important part of a story, the climax is the biggest plot point, which puts our characters in a situation wherein a choice must be made that will affect the rest of the story.

This is the critical moment that all the rising action has been building up to, and the point at which the overarching conflict is finally addressed. What will the character(s) do, and what will happen as a result? Tensions are highest here, instilling in the reader a sense of excitement, dread, and urgency.

In classic tales of heroes, the climax would be when the hero finally faces the big monster, and the reader is left to wonder who will win and what this outcome could mean for the other characters and the world as a whole within the story.

#4: Falling Action

This is when the tension has been released and the story begins to wind down. We start to see the results of the climax and the main characters’ actions and get a sense of what this means for them and the world they inhabit. How did their choices affect themselves and those around them?

At this point, the author also ties up loose ends in the main plot and any subplots.

In To Kill a Mockingbird, we see the consequences of the trial and Atticus Finch’s involvement in it: Tom goes to jail and is shot and killed, and Scout and Jem are attacked by accuser Bob Ewell who blames their father for making a fool out of him during the trial.

#5: Resolution/Denouement

This final plot point is when everything has been wrapped up and the new world—and the new sense of normalcy for the characters—has been established. The conflict from the climax has been resolved, and all loose ends have been neatly tied up (unless the author is purposely setting up the story for a sequel!).

There is a sense of finality and closure here, making the reader feel that there is nothing more they can learn or gain from the narrative.

The resolution can be pretty short—sometimes just a paragraph or so—and might even take the form of an epilogue, which generally takes place a while after the main action and plot of the story.

Be careful not to conflate «resolution» with «happy ending»—resolutions can be tragic and entirely unexpected, too!

In Romeo and Juliet, the resolution is the point at which the family feud between the Capulets and Montagues is at last put to an end following the deaths of the titular lovers.

What Is a Plot Diagram?

Many people use a plot diagram to help them visualize the plot definition and structure. Here’s what a basic plot diagram looks like:

The triangular part of the diagram indicates changing tensions in the plot. The diagram begins with a flat, horizontal line for the exposition, showing a lack of tension as well as what is normal for the characters in the story.

This elevation changes, however, with the rising action, or immediately after the conflict has been introduced. The rising action is an increasing line (indicating the building of tension), all the way up until it reaches the climax—the peak or turning point of the story, and when everything changes.

The falling action is a decreasing line, indicating a decline in tension and the wrapping up of the plot and any subplots. After, the line flatlines once more into a resolution—a new sense of normal for the characters in the story.

You can use the plot diagram as a reference when writing a story and to ensure you have all major plot points.

4 Plot Examples From Literature

While most plots follow the same basic structure, the details of stories can vary quite a bit! Here are four plot examples from literature to give you an idea of how you can use the fundamental plot structure while still making your story entirely your own.

#1: Hamlet by William Shakespeare

Exposition: The ghost of Hamlet’s father—the former king—appears one night instructing his son to avenge his death by killing Claudius, Hamlet’s uncle and the current king.

Rising Action: Hamlet struggles to commit to avenging his father’s death. He pretends to go crazy (and possibly becomes truly mad) to confuse Claudius. Later, he passes up the opportunity to kill his uncle while he prays.

Climax: Hamlet stabs and kills Polonius, believing it to be his uncle. This is an important turning point at which Hamlet has committed himself to both violence and revenge. (Another climax can be said to be when Hamlet duels Laertes.)

Falling Action: Hamlet is sent to England but manages to avoid execution and instead returns to Denmark. Ophelia goes mad and dies. Hamlet duels Laertes, ultimately resulting in the deaths of the entire royal family.

Resolution: As he lay dying, Hamlet tells Horatio to make Fortinbras the king of Denmark and to share his story. Fortinbras arrives and speaks hopefully about the future of Denmark.

#2: Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë

Exposition: Lockwood arrives at Wuthering Heights to meet with Heathcliff, a wealthy landlord, about renting Thrushcross Grange, another manor just a few miles away. While staying overnight, he sees the ghost of a woman named Catherine. After settling in at the Grange, Lockwood asks the housekeeper, Nelly Dean, to relay to him the story of Heathcliff and the Heights.

Rising Action: Most of the rising action takes place in the past when Catherine and Heathcliff were young. We learn that the two children were very close. One day, a dog bite forces Catherine to stay for several weeks at the Grange where the Lintons live, leading her to become infatuated with the young Edgar Linton. Feeling hurt and betrayed, Heathcliff runs away for three years, and Catherine and Edgar get married. Heathcliff then inherits the Heights and marries Edgar’s sister, Isabella, in the hopes of inheriting the Grange as well.

Climax: Catherine becomes sick, gives birth to a daughter named Cathy, and dies. Heathcliff begs Catherine to never leave him, to haunt him—even if it drives him mad.

Falling Action: Many years pass in Nelly’s story. A chain of events allows Heathcliff to gain control of both the Heights and the Grange. He then forces the young Cathy to live with him at the Heights and act as a servant. Lockwood leaves the Grange to return to London.

Resolution: Six months later, Lockwood goes back to see Nelly and learns that Heathcliff, still heartbroken and now tired of seeking revenge, has died. Cathy and Hareton fall in love and plan to get married; they inherit the Grange and the Heights. Lockwood visits the graves of Catherine and Heathcliff, noting that both are finally at peace.

#3: Carrie by Stephen King

Exposition: Teenager Carrie is an outcast and lives with her controlling, fiercely religious mother. One day, she starts her period in the showers at school after P.E. Not knowing what menstruation is, Carrie becomes frantic; this causes other students to make fun of her and pelt her with sanitary products. Around this time, Carrie discovers that she has telekinetic powers.

Rising Action: Carrie practices her telekinesis, which grows stronger. The students who previously tormented Carrie in the locker room are punished by their teacher. One girl, Sue, feels remorseful and asks her boyfriend, Tommy, to take Carrie to the prom. But another girl, Chris, wants revenge against Carrie and plans to rig the prom queen election so that Carrie wins. Carrie attends the prom with Tommy and things go well—at first.

Climax: After being named prom queen, Carrie gets onstage in front of the entire school only to be immediately drenched with a bucket of pig’s blood, a plot carried out by Chris and her boyfriend, Billy. Everybody laughs at Carrie, who goes mad and begins using her telekinesis to start fires and kill everyone in sight.

Falling Action: Carrie returns home and is attacked by her mother. She kills her mother and then goes outside again, this time killing Chris and Billy. As Carrie lay dying, Sue comes over to her and Carrie realizes that Sue never intended to hurt her. She dies.

Resolution: The survivors in the town must come to terms with the havoc Carrie wrought. Some feel guilty for not having helped Carrie sooner; Sue goes to a psychiatric hospital. It’s announced that there are no others like Carrie, but we are then shown a letter from a mother discussing her young daughter’s telekinetic abilities.

#4: Twilight by Stephenie Meyer

Exposition: Bella Swan is a high school junior who moves to live with her father in a remote town in Washington State. She meets a strange boy named Edward, and after an initially awkward meeting, the two start to become friends. One day, Edward successfully uses his bare hands to stop a car from crushing Bella, making her realize that something is very different about this boy.

Rising Action: Bella discovers that Edward is a vampire after doing some research and asking him questions. The two develop strong romantic feelings and quickly fall in love. Bella meets Edward’s family of vampires, who happily accept her. When playing baseball together, however, they end up attracting a gang of non-vegetarian vampires. One of these vampires, James, notices that Bella is a human and decides to kill her. Edward and his family work hard to protect Bella, but James lures her to him by making her believe he has kidnapped her mother.

Climax: Tricked by James, Bella is attacked and fed on. At this moment, Edward and his family arrive and kill James. Bella nearly dies from the vampire venom in her blood, but Edward sucks it out, saving her life.

Falling Action: Bella wakes up in the hospital, heavily injured but alive. She still wants to be in a relationship with Edward, despite the risks involved, and the two agree to stay together.

Resolution: Months later, Edward takes Bella to the prom. The two have a good time. Bella tells Edward that she wants him to turn her into a vampire right then and there, but he refuses and pretends to bite her neck instead.

Conclusion: So What Is the Plot of a Story?

What is plot? Basically, it’s the chain of events in a story. These events must be purposeful and organized in a logical manner that entices the reader, builds tension, and provides a resolution.

All plots have a beginning, middle, and end, and usually contain the following five points in this order:

#1: Exposition/introduction

#2: Rising action

#3: Climax/turning point

#4: Falling action

#5: Resolution/denouement

Sketching out a plot diagram can help you visualize your story and get a clearer sense for where the climax is, what tensions you’ll need to have in order to build up to this turning point, and how you can offer a tight conclusion to your story.

What’s Next?

What is plot? A key literary element as it turns out. Learn about other important elements of literature in our guide. We’ve also got a list of top literary devices you should know.

Interested in writing poetry? Then check out our picks for the 20 most critical poetic devices.

Need more help with this topic? Check out Tutorbase!

Our vetted tutor database includes a range of experienced educators who can help you polish an essay for English or explain how derivatives work for Calculus. You can use dozens of filters and search criteria to find the perfect person for your needs.

Have friends who also need help with test prep? Share this article!

Hannah received her MA in Japanese Studies from the University of Michigan and holds a bachelor’s degree from the University of Southern California. From 2013 to 2015, she taught English in Japan via the JET Program. She is passionate about education, writing, and travel.

Student and Parent Forum

Our new student and parent forum, at ExpertHub.PrepScholar.com, allow you to interact with your peers and the PrepScholar staff. See how other students and parents are navigating high school, college, and the college admissions process. Ask questions; get answers.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we’ll reply!

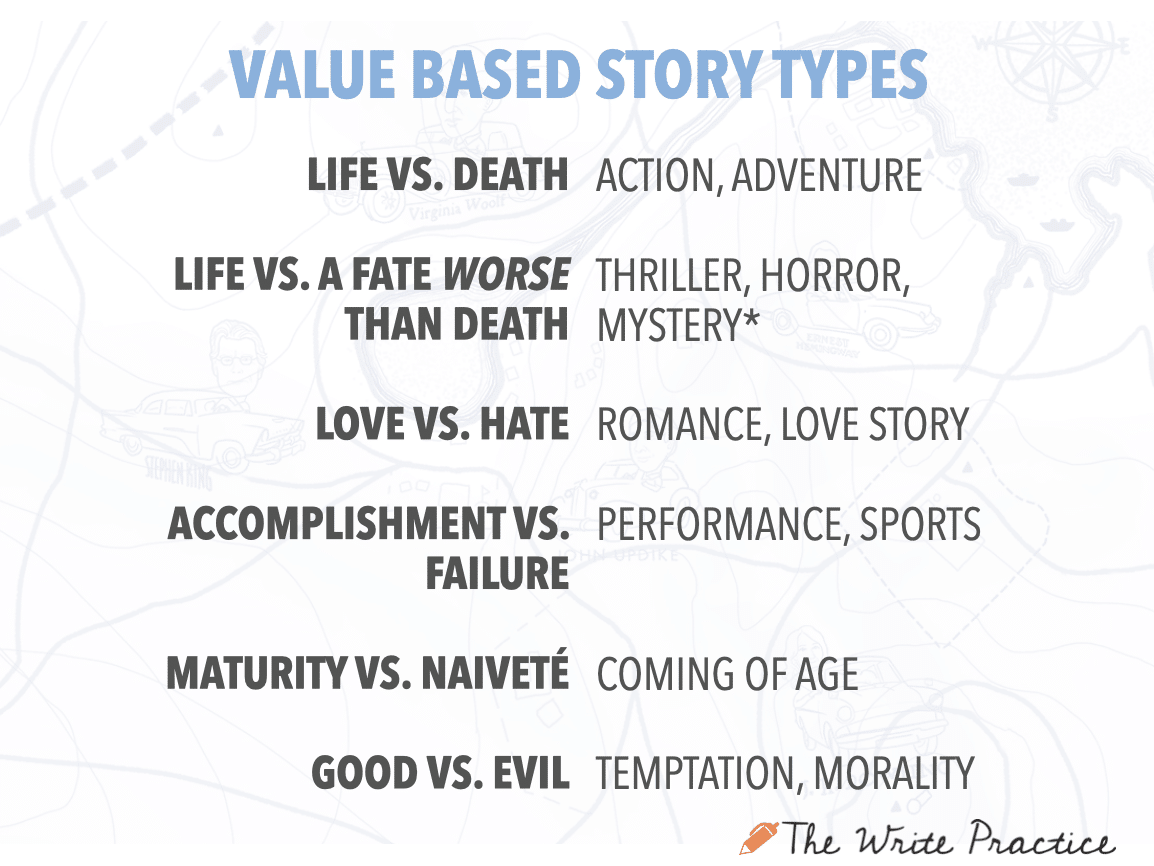

The 10 Types of Stories and How to Master Them

How do you write a best-selling novel or an award-winning screenplay? You might say, great writing or unique characters or thrilling conflict. But so much of writing a great story is knowing and mastering the type of story you’re trying to tell.

What are the types of stories? And how do you use them to tell a great story?

In this article, we’re going to cover the ten types of stories, share which tend to become best-sellers, and share the hidden values that help you master each type.

But first, what do I mean by “types of stories”?

Want to learn more about plot types and story structure? My #1 Amazon best-selling book The Write Structure explores the hidden structures behind bestselling and award-winning stories. If you want to learn more about how to write a great story, by mastering storytelling musts like the exposition literary definition, you can get the book for a limited time low price. Click here to get The Write Structure ($5.99).

Definition of Story Types

As stories have evolved for thousands of years, they began to fall into patterns called story types. These types tend to operate on the same underlying values. They also share similar structures, characters, and what Robert McKee calls obligatory scenes.

But Wait, Do Story Types Really Exist?

First, I want to address some discomfort you might be feeling with this idea. If you think that stories are magical and mystical, and the idea of putting them in a box feels terrible to you, I just want to say, I get that. I feel like that about stories, too!

You see, there are two ways you can figure out the patterns that stories take—the different types of stories.

You can start with stories themselves: looking through hundreds or even thousands until you get to four, seven, twelve, or even thirty-six master plots. This is what Christopher Booker did with his excellent guide The Seven Basic Plots: Why We Tell Stories, and you can get breakdowns of each of his types here.

And that can be helpful, certainly, but what about stories that are a little strange, genre-breaking, or out of the box?

Do they not have a “type”?

The other way you can figure out the types of stories is by going deeper, to the underlying reasons humans tell stories in the first place, the reason we’ve been telling stories for thousands of years, all the way back to the campfire stories our ancestors told each other.

Why do we tell stories? The reason humans have always told stories (and always will) is because we want something.

Maybe we want something as simple as to stay alive. This was one reason our long-ago ancestors told stories about surviving attacks from ferocious beasts.

Maybe we want love or belonging, so we tell great love stories about couples destined (or doomed) to be together.

Maybe we want to become the best version of ourselves. We tell stories about how people have overcome adversity, even pushed back against their narrow-minded communities, to fully self-actualize.

Or maybe we want to tell stories about what it’s like to transcend, to go beyond yourself and your circumstances and serve the good of the whole community, the whole world, and so we tell stories about sacrifice and great heroism.

In other words, basic story types arise from values, from the things humans want, and the great thing is, there has been a lot of research into the values humans find to be universal.

Story Types Are Defined by 6 Values

Great, bestselling stories are about values.

Value Definition

Value, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, is the regard that something is held to deserve; the importance, worth, or usefulness of something.

In other words, a value is something you admire, something you want. If you value something, it means you think it’s good.

Values in Stories

Here are some examples of things you might value:

This could easily become a never-ending list.

But if you think about it, every value can be distilled to six essential human values. Building off of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, these values are as follows (credit to Robert McKee and Shawn Coyne for introducing me to these concepts):

Once you distill these values, you can turn these values into scales, because these values are usually in conflict with their opposite.

In fact, it is the conflict between these values that generate the movement and change that makes the story work.

These are the same values that drive good storytelling.

If you take them a step further you can take these value scales and map them to different types of stories—or plot types. Here’s how it works:

These plot types transcend genre. You can have a sci-fi love story, a historical thriller, a fantasy performance story, a mystery romance story, or even a young adult adventure story.

Your story’s plot type will determine much of your story: the scenes you must include, the conventions and tropes you employ, your characters (including protagonists, side characters, and antagonists), and more.

How does that work practically? Let’s look at a couple of examples:

Adventure Story Type Example

Let’s look at a classic example, The Hobbit, one of the best-selling novels of all time, by J.R.R. Tolkien.

When you’re trying to understand the type of story you’re trying to tell, the first question to ask is, “What value scale do a majority of the scenes move on?”

The question constantly coming up in The Hobbit is this: “Is Bilbo Baggins going to survive the run-ins with the spiders and trolls and orcs, or is he not going to survive?”

The Hobbit, at its core, is an adventure story, and that means that a majority of the scenes move on the Life vs. Death Scale.

While there are certainly scenes that fall on the Good vs. Evil and Maturity vs. Naïveté scales, it is the Life vs. Death scale that most of the scenes move on.

The 10 Types of Stories

Now that we’ve looked at an example, let’s break down each of the ten main story types and talk about how they work.

Each of these plot types has typical archetypes for their inciting incidents and main event/climax. While you can certainly tweak or even re-work these archetypes, it’s best to understand how they work and ensure that your new version of the event can bring out as much of the conflict as the typical method.

For more on this, check out our respective guides on inciting incidents and climaxes.

These ideas are not new, and I also have to acknowledge a huge debt to the story theorists who have gone before me, especially Blake Snyder, author of Save the Cat; Robert McKee, author of Story; and Shawn Coyne, author of Story Grid.

1. Adventure Story Type

Value: Life vs. Death

Inciting Incident Archetype(s): The Quest for the MacGuffin. A MacGuffin is an object, place, or (sometimes) person of great importance to the characters of the story, and the thing that drives the plot. For example, the ring in Lord of the Rings, the horcruxes in Harry Potter, or the ark of the covenant in Indiana Jones. Most adventure plot types revolve around a MacGuffin, and the inciting incident involves introducing the MacGuffin and its importance.

Main Event: Final showdown with the bad guys (while trying to get the MacGuffin).

Examples: The Odyssey, The Lord of the Rings, The Hobbit, Beowulf, Alice in Wonderland

Note: Most (but not all) hero’s journey stories fit this type, as well as any “voyage and return” type plots.

2. Action Story Type

Value: Life vs. Death

Inciting Incident Archetype(s):

Main event: Showdown with the Bad Guy

Examples: The Count of Monte Cristo, Hunger Games

3. Horror Story Type

Value: Life vs. Fate Worse than Death

Inciting Incident Archetype(s):

Main Event: Confrontation of the Monster

Examples: The Shining, The Exorcist, The Haunting of Hill House, The Grudge, Candyman, Macbeth

4. Thriller Story Type

Value: Life vs. a Fate Worse than Death

The thriller plot type is closely related to the Action and Mystery plot types. Both begin with some kind of crime, contain investigative elements, and climax with the hero at the mercy of the villain.

However, what makes it unique is there is always a horror element, a sense that this is somehow worse, more monstrous, than your average crime.

It’s a fine line, though, and many story theories, like those from Robert McKee, make no distinction between the Thriller with the Action plot types.

Inciting Incident Archetype(s): Show me the (Monstrously Brutalized) Body. As with the mystery plot type (below), Thriller plot types contain an inciting incident in which a crime is discovered, whether it’s a literal dead body, a theft, or some other type of crime. However, with thriller, the crime has a horror feel to it, the crime being particularly monstrous, brutal, etc.

Main Event: Hero at the Mercy of the Villain. In the climactic scene, the main character is caught by the antagonist and at their mercy, showing their (temporary) dominance. Depending on the story arc, the protagonist may reverse their situation or succumb to the antagonist.

5. Mystery Story Type

Value: Life vs. Fate Worse than Death (in the sense of a restoration of Justice)

Inciting Incident Archetype(s): Show Me the Body. All mystery plot types contain an inciting incident in which a crime is discovered, whether it’s a literal dead body, a theft, or some other type of crime.

Main Event: The Confession. The antagonist confesses to the crime and justice, the power of life over death, is restored.

Examples: The Inspector Gamache series, Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets (as a subplot)

6. Romance/Love Story Type

Value: Love vs. Hate

Inciting Incident Archetype(s): Meet Cute OR We Should Break Up. Love plots either begin with the couple meeting or breaking up/getting into some kind of conflict. The meet cute inciting incident involves the couple meeting in some unexpected, comedic, and/or often shambolic way, often while having extreme distaste for each other at the outset.

Main Event: Proof of Love. After some kind of separation, the protagonist must overcome obstacles to prove their love to the other.

Examples: A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Romeo and Juliet, 10 Things I Hate About You and most Rom-coms

For more on writing or editing a love story, check out this coaching video:

7. Performance/Sports Story Type

Value: Accomplishment vs. Failure

The core value of the performance story type is esteem, which is all about looking good in front of your community, usually after accomplishing a great feat or winning a widely recognized competition.

Inciting Incident Archetype(s): Entry into the Big Tournament. Performance stories—whether the performance medium is sports, music, art, or some other avenue—all contain an inciting incident where the characters enter a major tournament, performance, or competition. This competition is usually an actual event (e.g. the Olympics, the state championship) but may be a less formal competition.

Main Event: The Big Tournament. After preparing for the big event by overcoming smaller obstacles throughout the story, the protagonist faces their challenger in the final competition.

Examples: Miracle, Cobra Kai, Ghost, Hamilton

8. Coming of Age Story Type

Value: Maturity vs. Immaturity

Inciting Incident Archetype(s):

Main Event: The Revelation. In a moment of crisis, the protagonist has a major worldview revelation, leading them to see the world in a new, more sophisticated way.

Examples: How to Train Your Dragon, Catcher in the Rye, Good Will Hunting, Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, The Ugly Duckling

9. Temptation/Morality Story Type

Value: Good vs. Evil

The value of good vs. evil here is not “The Good Guys” vs. “The Bad Guys.” That plot type is usually action. Instead, the evil is within the character, and they must choose whether to do the good, self-sacrificial thing or the selfish, evil thing.

Inciting Incident Archetype(s): Let’s Make a Deal. Often temptation stories begin with a proverbial “deal with the devil,” in which the character is tempted to do something they think is relatively harmless but might give them great reward.

Main Event: Judgement Day. Facing the consequences of their actions, the main character must either embrace their consequences and change or continue to attempt to escape them and face damnation.

Examples: Wall Street, A Christmas Carol

10. Combinations (Advanced!)

While all great stories are driven by values and the conflict between them, many stories combine plot types and/or value scales in unique ways, creating new plot types of their own.

Often this approach works best with either longer works, epics that combine many arcs into one story, or shorter works, like short stories, which may not contain all the elements of longer, more established plot types.

However, combining or rearranging plot types is considered advanced. Consider before you attempt to come up with your own completely unique plot type, especially if you are a new writer, as you risk the story not working or getting lost in the plot and failing to finish.

Remember: working with an established plot type requires just as much creativity and flair for coming up with dramatic situations as invention your own.

Subtypes

While most popular stories will fit within the ten plot types above, you could also get more specific by exploring subtypes.

Subtypes are more specific plots with unique conventions, tropes, and characters. Examples of subtypes include revenge plots, a subtype of action plots; heist plots, a subplot of adventure stories; or obsession love stories.

Most stories that work will fall somewhere into the above plot types, and all stories that work will fall into the six value scales.

These 10 Types of Stories Work for Any Story Arc

Great novels, films, memoirs, and plays come in many shapes, but researchers from the University of Vermont have identified six primary shapes, all of which we talk about in detail in our story arcs guide. Here are the six:

These arcs are independent of plot type.

You can have a tragic Icarus mystery story where the villain gets away. You can have a Cinderella horror story where the monster starts out bad, then seems to be nearly defeated, only to come back stronger and then finally get destroyed in the end.

Even though certain genres and plot types have tendencies toward specific plotlines, the types work independently of arc. Choose any combination of the arcs and plot types, and it will still work.

2 Tips About How to Use These Plot Types

How do you actually write a book with these plot types in mind? Follow these two tips:

1. First, Know Your Values

Bad books, stories that don’t work, don’t know what their values are.

Or they’re trying to have every single value possible.

You can’t do that if you want to tell a great story. You have to choose! If you want to master the type of story you’re trying to tell, start with finding the story’s value.

Here’s a video that shows how one author figured out their plot type by diving into the value at the center of their story.

2. Focus on Conflict Between Values

You’ve heard your stories need conflict, but that doesn’t mean more arguments and car chases.

The kind of conflict your stories need more of is between values, and the way to master any type of story is to put the story’s main value in conflict with its opposite.

If you’re writing an adventure story, that means you need to have life and death moments.

If you’re writing a thriller, you need to have moments of life vs. fate worse than death.

If you’re writing a love story, you need to have as many moments of negative love, of anger, disillusion, and even hatred, as you do love.

If you’re writing a sports story, there have to be as many moments of near failure, or actual failure, as there are of success.

If you’re writing a coming-of-age story, then you need to include moments where the growing maturity of the character is put into conflict with its opposite, immaturity.

And finally, if you’re writing a temptation or morality story, then you need moments of temptation—where the character genuinely considers if they should take actions they know are wrong because of how it could benefit them or solve a greater problem.

So how about you? What type of story are you trying to tell? Let us know in the comments.

Put the types of story to use now with the following creative writing exercise.

First, choose one of the story scales above.

Then, outline the inciting incident scene or another scene in which your protagonist is faced with the negative value in that scale.

Finally, set a timer for fifteen minutes. Write as much of your scene as you can.

When your time is up, post your scene in the practice box below. And when you’re done, check out others who have shared their scenes. Let them know what you think!

It features some kind of story of plot which is made using drawings

Plot is a literary device that writers use to structure what happens in a story. However, there is more to this device than combining a sequence of events. Plots must present an event, action, or turning point that creates conflict or raises a dramatic question, leading to subsequent events that are connected to each other as a means of “answering” the dramatic question and conflict. The arc of a story’s plot features a causal relationship between a beginning, middle, and end in which the conflict is built to a climax and resolved in conclusion.

For example, A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens features one of the most well-known and satisfying plots of English literature.

I will honour Christmas in my heart, and try to keep it all the year. I will live in the Past, the Present, and the Future. The Spirits of all Three shall strive within me. I will not shut out the lessons that they teach.

Dickens introduces the protagonist, Ebenezer Scrooge, who is problematic in his lack of generosity and participation in humanity–especially during the Christmas season. This conflict results in three visitations by spirits that help Scrooge’s character and the reader understand the causes for the conflict. The climax occurs as Scrooge’s dismal future is foretold. The above passage reflects the second chance given to Scrooge as a means of changing his future as well as his present life. As the plot of Dickens’s story ends, the reader finds resolution in Scrooge’s changed attitude and behavior. However, if any of the causal events were removed from this plot, the story would be far less valuable and effective.

Common Examples of Plot Types

Aristotle’s Plot Structure Formula

Though this principle may seem obvious to modern readers, in his work Poetics, Aristotle first developed the formula for plot structure as three parts: beginning, middle, and end. Each of these parts is purposeful, integral, and challenging for writers. It

Freytag’s Pyramid

Differences Between Narrative and Plot

Plot and narrative are both literary devices that are often used interchangeably. However, there is a distinction between them when it comes to storytelling. Plot involves causality and a connected series of events that make up a story. Plot refers to what actions and/or events take place in a story and the causal relationship between them.

Narrative encompasses aspects of a story that include choices by the writer as to how the story is told, such as point of view, verb tense, tone, and voice. Therefore, the plot is a more objective literary device in terms of a story’s definitive events. Narrative is more subjective as a literary device in that there are many choices a writer can make as to how the same plot is told and revealed to the reader.

Three Basic Patterns of Plot – William Foster-Harris

Master Plots – Ronald R. Tobias

The term master plots occur in the book of Ronald R. Tobias, 20 Master Plots. Some of the important ones are Quest, Adventure, Pursuit, and Rescue. These are followed by Escape, Revenge, The riddle, Rivalry, and Underdog, while Temptation, Metamorphosis, and Transformation follow them. Some others are Maturing, Love, and Forbidden Love. Sacrifice and Discovery are two other master plots with Wretched Excess, Ascension, and Descension following them. The important feature of these plots is that they all follow the style their title suggests.

Seven Types of Plots – Jessamyn West

Why it is Good to Break Traditional Plot Structures

Although most critics are very strict about a story having a plot, it is quite unusual to break the conventional structures and create a new one. This creativity is the hallmarks of a literary piece as breaking the traditional plot structure makes the literary piece in the process a unique addition to the long list of such other pieces. This also makes the writer flout new ideas about plot structures, making him a pioneer in such plots. It often happens in postmodern fiction to break away from traditions in creating plots such as Slaughterhouse-Five by Kurt Vonnegut presents a non-linear storyline.

Linear and Non-Linear Plots

These two very simple terms, linear and non-linear in the literary world with reference to plots, define how a plot has been structured. A linear plot is constructed on the idea of chronological order having a clear beginning, a defined middle, and a definite ending. However, when an author, such as the referred novel in the above example shows, breaks away from the normal plot structures, it becomes a non-linear plot. It does not have any beginning or for that matter any ending or middle. It just presents fractured and broken thoughts or incidents in a way that the readers have to construct their own story.

Examples of Plot in Literature

When readers remember a work of literature, whether it’s a novel, short story, play, or narrative poem, their lasting impression often is due to the plot. The cause and effect of events in a plot are the foundation of storytelling, as is the natural arc of a story’s beginning, middle, and end. Literary plots resonate with readers as entertainment, education, and elemental to the act of reading itself. Here are some examples of plot in literature:

Example 1: Romeo and Juliet (Prologue) – William Shakespeare

Two households, both alike in dignity

(In fair Verona, where we lay our scene),

From ancient grudge break to new mutiny,

Where civil blood makes civil hands unclean.

From forth the fatal loins of these two foes

A pair of star-crossed lovers take their life;

Whose misadventured piteous overthrows

Doth with their death bury their parents’ strife.

The fearful passage of their death-marked love

And the continuance of their parents’ rage,

Which, but their children’s end, naught could remove,

Is now the two hours’ traffic of our stage;

The which, if you with patient ears attend,

What here shall miss, our toil shall strive to mend.

In the prologue of Shakespeare’s famous tragedy, the arc of the plot is told–including the outcome of the story. However, though the overall plot is revealed before the story begins, this does not detract from the portrayal of the events in the story and the relationship between their cause and effect. Each character’s action drives forward connected events that build to a climax and then a tragic resolution, so that even if the reader/viewer knows what will happen, the play remains an engaging and memorable literary work.

Example 2: Six-word-long story, often attributed to Ernest Hemingway

For sale, baby shoes, never worn.

This famous six-word short story is attributed to Ernest Hemingway, although there has been no indisputable substantiation that it is his creation. Aside from its authorship, this story demonstrates the power of plot as a literary device and in particular the effectiveness of Aristotle’s formula. Through just six words, the plot of this story has a beginning, middle, and end that readers can identify. In addition, the plot allows readers to interpret the causality of the story’s events depending on the manner in which they view and interpret the narrative.

Example 3: Don Quixote – Miguel de Cervantes

“Destiny guides our fortunes more favorably than we could have expected. Look there, Sancho Panza, my friend, and see those thirty or so wild giants, with whom I intend to do battle and kill each and all of them, so with their stolen booty we can begin to enrich ourselves. This is noble, righteous warfare, for it is wonderfully useful to God to have such an evil race wiped from the face of the earth.”

“What giants?” Asked Sancho Panza.

“The ones you can see over there,” answered his master, “with the huge arms, some of which are very nearly two leagues long.”

“Now look, your grace,” said Sancho, “what you see over there aren’t giants, but windmills, and what seems to be arms are just their sails, that go around in the wind and turn the millstone.”

“Obviously,” replied Don Quijote, “you don’t know much about adventures.”

Don Quixote is considered the first modern novel, and the complexity of its plot is one of the reasons for this distinction. Each event that takes place in this overall hero’s journey is connected to and causes other actions in the story, bringing about a resolution at the end. This novel by de Cervantes features subplots as well, yet the story arc of the character reflects all elements of both Aristotle’s plot formula and Freytag’s Pyramid.

Synonyms of Plot

There are several synonyms that come close to the plot in meanings such as narrative, theme, events, tales, mythos, and subject, yet they are all literary devices in their own right. They do not replace the plot.