You must allow me to tell you how ardently i admire and love you

You must allow me to tell you how ardently i admire and love you

„You must allow me to tell you how ardently I admire and love you.

Источник: Pride and Prejudice

Джейн Остин 89

Похожие цитаты

Вариант: In vain I have struggled. It will not do. My feelings will no longer be repressed. You must allow me to tell you how ardently I admire and love you.

Источник: Pride And Prejudice

— Jane Austen, книга Pride and Prejudice

Источник: Pride and Prejudice

Te quireo como eres, pero no me digas cómo eres.

Voces (1943)

— Eric Clapton English musician, singer, songwriter, and guitarist 1945

— Ally Carter, книга Only the Good Spy Young

Источник: Only the Good Spy Young

«No, it is not you I love so ardently. » (1841)

Poems

Источник: The Haystack Syndrome (1990), p. 26

— Jane Austen, книга Pride and Prejudice

Источник: Pride and Prejudice

— Pat Frank, книга Alas, Babylon

Источник: Alas, Babylon

Words of Love

Song lyrics, Buddy Holly (1958)

Источник: The Works of Aretino: Biography: de Sanctis. The letters, 1926, p. 152

— Donald J. Trump 45th President of the United States of America 1946

Trump was answering what his basis was for claiming that the coronavirus emerged from a virology lab in the Wuhan city of China, as quoted by * 2020-05-01

‘It Came Out Of China, Could Have Been Stopped’: Prez Donald Trump On Coronavirus

Jane Austen: Pride and Prejudice

Chapter 34

When they were gone, Elizabeth, as if intending to exasperate herself as much as possible against Mr. Darcy, chose for her employment the examination of all the letters which Jane had written to her since her being in Kent. They contained no actual complaint, nor was there any revival of past occurrences, or any communication of present suffering. But in all, and in almost every line of each, there was a want of that cheerfulness which had been used to characterise her style, and which, proceeding from the serenity of a mind at ease with itself and kindly disposed towards everyone, had been scarcely ever clouded. Elizabeth noticed every sentence conveying the idea of uneasiness, with an attention which it had hardly received on the first perusal. Mr. Darcy’s shameful boast of what misery he had been able to inflict, gave her a keener sense of her sister’s sufferings. It was some consolation to think that his visit to Rosings was to end on the day after the next—and, a still greater, that in less than a fortnight she should herself be with Jane again, and enabled to contribute to the recovery of her spirits, by all that affection could do.

She could not think of Darcy’s leaving Kent without remembering that his cousin was to go with him; but Colonel Fitzwilliam had made it clear that he had no intentions at all, and agreeable as he was, she did not mean to be unhappy about him.

While settling this point, she was suddenly roused by the sound of the door-bell, and her spirits were a little fluttered by the idea of its being Colonel Fitzwilliam himself, who had once before called late in the evening, and might now come to inquire particularly after her. But this idea was soon banished, and her spirits were very differently affected, when, to her utter amazement, she saw Mr. Darcy walk into the room. In an hurried manner he immediately began an inquiry after her health, imputing his visit to a wish of hearing that she were better. She answered him with cold civility. He sat down for a few moments, and then getting up, walked about the room. Elizabeth was surprised, but said not a word. After a silence of several minutes, he came towards her in an agitated manner, and thus began:

«In vain I have struggled. It will not do. My feelings will not be repressed. You must allow me to tell you how ardently I admire and love you.»

How ardently I admire and love you…

Pride and Prejudice

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics onTwitter and Facebook.

On 28 January 1813, Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen was published. Originally titled ‘First Impressions’, Austen was forced to re-title it with a phrase from Frances Burney’s Cecilia after the publication of Margaret Holford’s First Impressions. We’ve paired an extract from the book with a scene from the most recent dramatization to see how Austen’s words have survived the centuries.

While settling this point, she was suddenly roused by the sound of the door bell, and her spirits were a little fluttered by the idea of its being Colonel Fitzwilliam himself, who had once before called late in the evening, and might now come to enquire particularly after her.

But this idea was soon banished, and her spirits were very differently affected, when, to her utter amazement, she saw Mr. Darcy walk into the room. In an hurried manner he immediately began an enquiry after her health, imputing his visit to a wish of hearing that she were better. She answered him with cold civility. He sat down for a few moments, and then getting up walked about the room. Elizabeth was surprised, but said not a word. After a silence of several minutes he came towards her in an agitated manner, and thus began,

‘In vain have I struggled. It will not do. My feelings will not be repressed. You must allow me to tell you how ardently I admire and love you.’

Elizabeth’s astonishment was beyond expression. She stared, coloured, doubted, and was silent. This he considered sufficient encouragement, and the avowal of all that he felt and had long felt for her, immediately followed. He spoke well, but there were feelings besides those of the heart to be detailed, and he was not more eloquent on the subject of tenderness than of pride. His sense of her inferiority––of its being a degradation––of the family obstacles which judgment had always opposed to inclination, were dwelt on with a warmth which seemed due to the consequence he was wounding, but was very unlikely to recommend his suit.

In spite of her deeply-rooted dislike, she could not be insensible to the compliment of such a man’s affection, and though her intentions did not vary for an instant, she was at first sorry for the pain he was to receive; till, roused to resentment by his subsequent language, she lost all compassion in anger. She tried, however, to compose herself to answer him with patience, when he should have done. He concluded with representing to her the strength of that attachment which, in spite of all his endeavours, he had found impossible to conquer; and with expressing his hope that it would now be rewarded by her acceptance of his hand. As he said this, she could easily see that he had no doubt of a favourable answer. He spoke of apprehension and anxiety, but his countenance expressed real security. Such a circumstance could only exasperate farther, and when he ceased, the colour rose into her cheeks, and she said,

‘In such cases as this, it is, I believe, the established mode to express a sense of obligation for the sentiments avowed, however unequally they may be returned. It is natural that obligation should be felt, and if I could feel gratitude, I would now thank you. But I cannot––I have never desired your good opinion, and you have certainly bestowed it most unwillingly. I am sorry to have occasioned pain to any one. It has been most unconsciously done, however, and I hope will be of short duration. The feelings which, you tell me, have long prevented the acknowledgment of your regard, can have little difficulty in overcoming it after this explanation.’

Mr. Darcy, who was leaning against the mantle-piece with his eyes fixed on her face, seemed to catch her words with no less resentment than surprise. His complexion became pale with anger, and the disturbance of his mind was visible in every feature. He was struggling for the appearance of composure, and would not open his lips, till he believed himself to have attained it. The pause was to Elizabeth’s feelings dreadful. At length, in a voice of forced calmness, he said,

‘And this is all the reply which I am to have the honour of expecting! I might, perhaps, wish to be informed why, with so little endeavour at civility, I am thus rejected. But it is of small importance.’

‘I might as well enquire,’ replied she, ‘why with so evident a design of offending and insulting me, you chose to tell me that you liked me against your will, against your reason, and even against your character? Was not this some excuse for incivility, if I was uncivil? But I have other provocations. You know I have. Had not my own feelings decided against you, had they been indifferent, or had they even been favourable, do you think that any consideration would tempt me to accept the man, who has been the means of ruining, perhaps for ever, the happiness of a most beloved sister?’

As she pronounced these words, Mr. Darcy changed colour; but the emotion was short, and he listened without attempting to interrupt her while she continued.

‘I have every reason in the world to think ill of you. No motive can excuse the unjust and ungenerous part you acted there. You dare not, you cannot deny that you have been the principal, if not the only means of dividing them from each other, of exposing one to the censure of the world for caprice and instability, the other to its derision for disappointed hopes, and involving them both in misery of the acutest kind.’

She paused, and saw with no slight indignation that he was listening with an air which proved him wholly unmoved by any feeling of remorse. He even looked at her with a smile of affected incredulity.

‘Can you deny that you have done it?’ she repeated.

With assumed tranquillity he then replied, ‘I have no wish of denying that I did every thing in my power to separate my friend from your sister, or that I rejoice in my success. Towards him I have been kinder than towards myself.’

Elizabeth disdained the appearance of noticing this civil reflection, but its meaning did not escape, nor was it likely to conciliate her.

‘But it is not merely this affair,’ she continued, ‘on which my dislike is founded. Long before it had taken place, my opinion of you was decided. Your character was unfolded in the recital which I received many months ago from Mr. Wickham. On this subject, what can you have to say? In what imaginary act of friendship can you here defend yourself? or under what misrepresentation, can you here impose upon others?’

‘You take an eager interest in that gentleman’s concerns,’ said Darcy in a less tranquil tone, and with a heightened colour.

‘Who that knows what his misfortunes have been, can help feeling an interest in him?’

‘His misfortunes!’ repeated Darcy contemptuously, ‘yes, his misfortunes have been great indeed.’

‘And of your infliction,’ cried Elizabeth with energy. ‘You have reduced him to his present state of poverty, comparative poverty. You have withheld the advantages, which you must know to have been designed for him. You have deprived the best years of his life, of that independence which was no less his due than his desert. You have done all this! and yet you can treat the mention of his misfortunes with contempt and ridicule.’

‘And this,’ cried Darcy, as he walked with quick steps across the room, ‘is your opinion of me! This is the estimation in which you hold me! I thank you for explaining it so fully. My faults, according to this calculation, are heavy indeed! But perhaps,’ added he, stopping in his walk, and turning towards her, ‘these offences might have been overlooked, had not your pride been hurt by my honest confession of the scruples that had long prevented my forming any serious design. These bitter accusations might have been suppressed, had I with greater policy concealed my struggles, and flattered you into the belief of my being impelled by unqualified, unalloyed inclination; by reason, by reflection, by every thing. But disguise of every sort is my abhorrence. Nor am I ashamed of the feelings I related. They were natural and just. Could you expect me to rejoice in the inferiority of your connections? To congratulate myself on the hope of relations, whose condition in life is so decidedly beneath my own?’

Elizabeth felt herself growing more angry every moment; yet she tried to the utmost to speak with composure when she said,

‘You are mistaken, Mr. Darcy, if you suppose that the mode of your declaration affected me in any other way, than as it spared me the concern which I might have felt in refusing you, had you behaved in a more gentleman-like manner.’

She saw him start at this, but he said nothing, and she continued, ‘You could not have made me the offer of your hand in any possible way that would have tempted me to accept it.’

Again his astonishment was obvious; and he looked at her with an expression of mingled incredulity and mortification. She went on.

‘From the very beginning, from the first moment I may almost say, of my acquaintance with you, your manners impressing me with the fullest belief of your arrogance, your conceit, and your selfish disdain of the feelings of others, were such as to form that ground-work of disapprobation, on which succeeding events have built so immoveable a dislike; and I had not known you a month before I felt that you were the last man in the world whom I could ever be prevailed on to marry.’

‘You have said quite enough, madam. I perfectly comprehend your feelings, and have now only to be ashamed of what my own have been. Forgive me for having taken up so much of your time, and accept my best wishes for your health and happiness.’

And with these words he hastily left the room, and Elizabeth heard him the next moment open the front door and quit the house. The tumult of her mind was now painfully great. She knew not how to support herself, and from actual weakness sat down and cried for half an hour. Her astonishment, as she reflected on what had passed, was increased by every review of it. That she should receive an offer of marriage from Mr. Darcy! that he should have been in love with her for so many months! so much in love as to wish to marry her in spite of all the objections which had made him prevent his friend’s marrying her sister, and which must appear at least with equal force in his own case, was almost incredible! it was gratifying to have inspired unconsciously so strong an affection. But his pride, his abominable pride, his shameless avowal of what he had done with respect to Jane, his unpardonable assurance in acknowledging, though he could not justify it, and the unfeeling manner in which he had mentioned Mr. Wickham, his cruelty towards whom he had not attempted to deny, soon overcame the pity which the consideration of his attachment had for a moment excited…

Pride and Prejudice has delighted generations of readers with its unforgettable cast of characters, carefully choreographed plot, and a hugely entertaining view of the world and its absurdities. With the arrival of eligible young men in their neighborhood, the lives of Mr. and Mrs. Bennet and their five daughters are turned inside out and upside down. Pride encounters prejudice, upward-mobility confronts social disdain, and quick-wittedness challenges sagacity, as misconceptions and hasty judgements lead to heartache and scandal, but eventually to true understanding, self-knowledge, and love. In this supremely satisfying story, Jane Austen balances comedy with seriousness, and witty observation with profound insight.

Our Privacy Policy sets out how Oxford University Press handles your personal information, and your rights to object to your personal information being used for marketing to you or being processed as part of our business activities.

We will only use your personal information to register you for OUPblog articles.

Or subscribe to articles in the subject area by email or RSS

You Must Allow Me To Tell You How Ardently I Admire and Love Natural Language Processing

It is a truth universally acknowledged that sentiment analysis is super fun, and Pride and Prejudice is probably my very favorite book in all of literature, so let’s do some Jane Austen natural language processing.

Project Gutenberg makes e-texts available for many, many books, including Pride and Prejudice which is available here. I am using the plain text UTF-8 file available at that link for this analysis. Let’s read the file and get it ready for analysis.

Munge the Data, But ELEGANTLY, As Would Befit Jane Austen

The plain text file has lines that are just over 70 characters long. We can read them in using the readr library, which is super fast and easy to use. Let’s use the skip and n_max options to leave out the Project Gutenberg header and footer information and just get the actual text of the novel. Lines of 70 characters are not really a big enough chunk of text to be useful for my purposes here (that’s not even a tweet!) so let’s use stringr to concatenate these lines in chunks of 10. That gives us sort of paragraph-sized chunks of text.

Maybe you don’t think for loops are elegant, actually, but I could not come up with a way to vectorize this.

Mr. Darcy Delivered His Sentiments in a Manner Little Suited to Recommend Them

To do the sentiment analysis, let’s use the NRC Word-Emotion Association Lexicon of Saif Mohammad and Peter Turney. You can read a bit more about the NRC sentiment dictionary and how it is used in one of my previous blog posts. It is implemented in R in the syuzhet package.

I was not sure, when I stopped to think about it, exactly how appropriate this tool is for analyzing 200-year-old text. Language changes over time and from what I can tell, the NRC lexicon is designed and validated to measure the sentiment in contemporary English. It was created via crowdsourcing on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk. However, it doesn’t seem to do badly on Jane Austen’s prose; the sentiment results are about what one would expect compared to a human reading of the meaning. If anything, the text in Pride and Prejudice involves more dramatic vocabulary than a lot of contemporary English prose and it is easier for a tool like the NRC dictionary to pick up on the emotions involved.

Let’s look at some examples.

So let’s start from a working hypothesis that the NRC lexicon can be applied to this novel and do the sentiment analysis for each chunk of text in our dataframe. At the same time, let’s make a linenumber that counts up through the novel.

Dividing Up the Volumes

Pride and Prejudice contains 61 chapters divided into three volumes; Volume I is Chapters 1-23, Volume II is Chapters 24-42, and Volume III is Chapters 43-61. Let’s find where these breaks between volumes have ended up.

Let’s make a volume factor for the dataframe and then restart the linenumber count at the beginning of each volume.

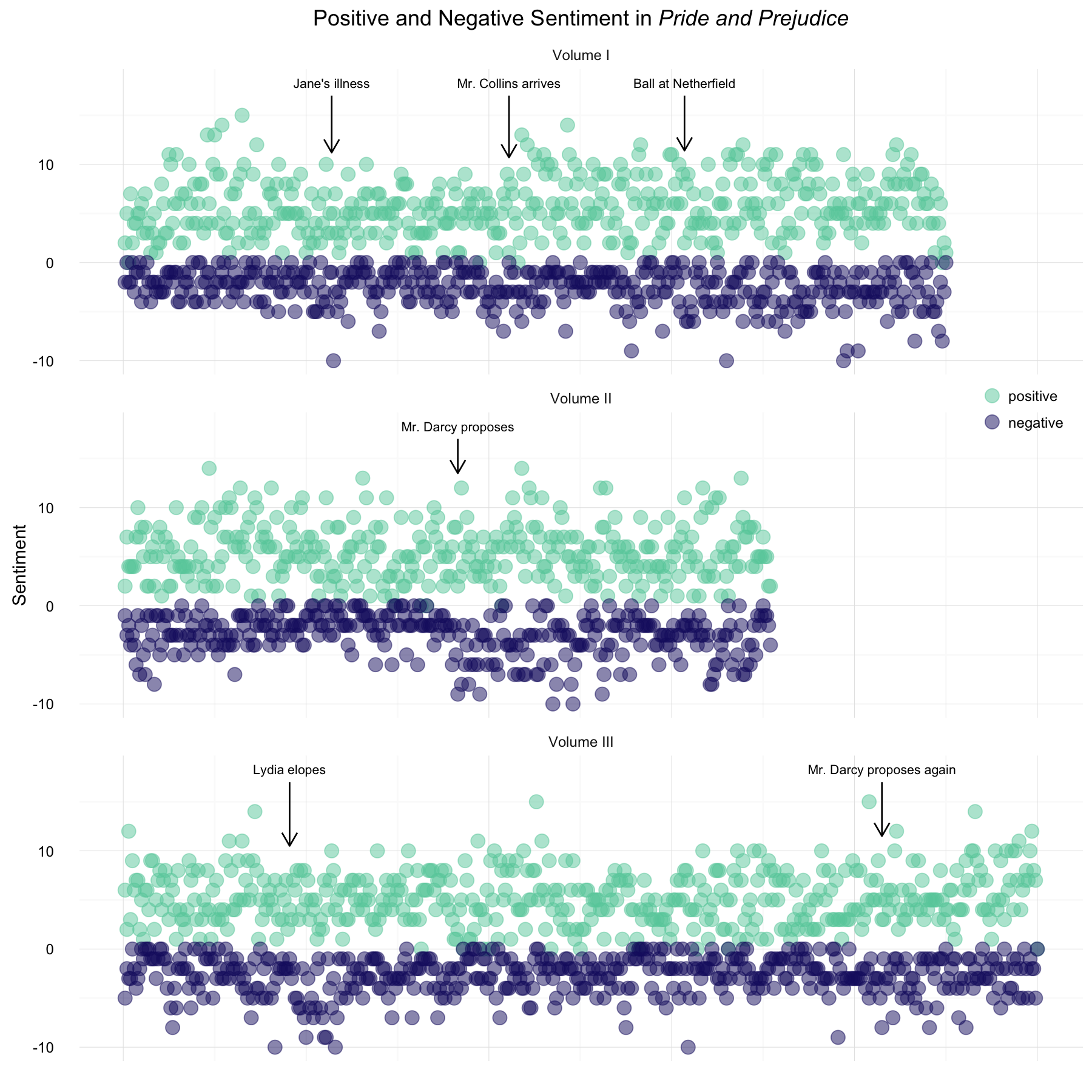

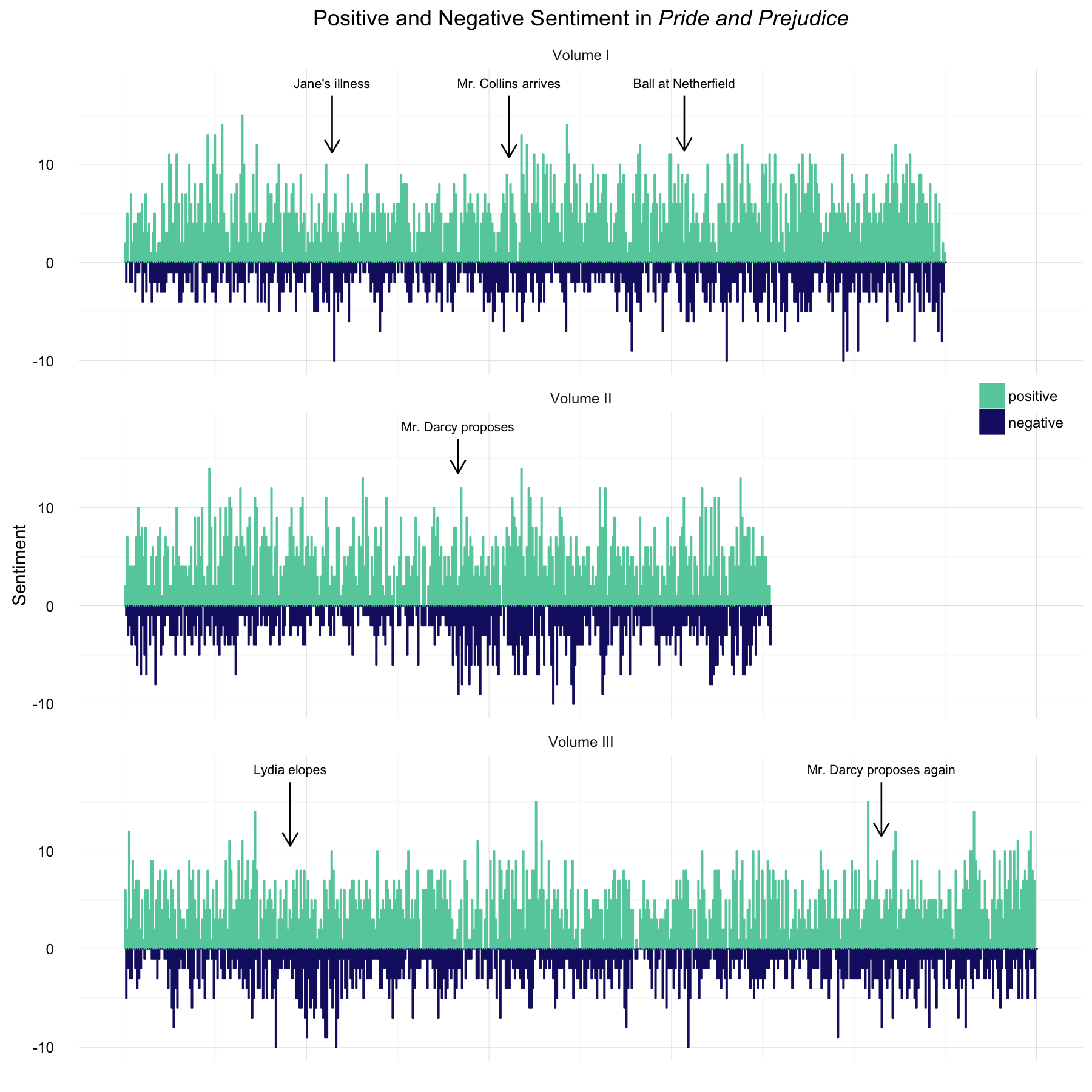

Positive and Negative Sentiment

First let’s look at the overall postive vs. negative sentiment in the text of Pride and Prejudice before looking at more specific emotions.

Here, each chunk of text has a score for the positive sentiment and the negative sentiment; a given chunk of text could have high scores for both, low scores for both, or any combination thereof. I have made the sign of the negative sentiment negative for plotting purposes. Let’s make a dataframe of some important events in the novel to annotate the plots; I found the chapters for these events and matched them up to the correct volumes and line numbers.

Now let’s plot the positive and negative sentiment.

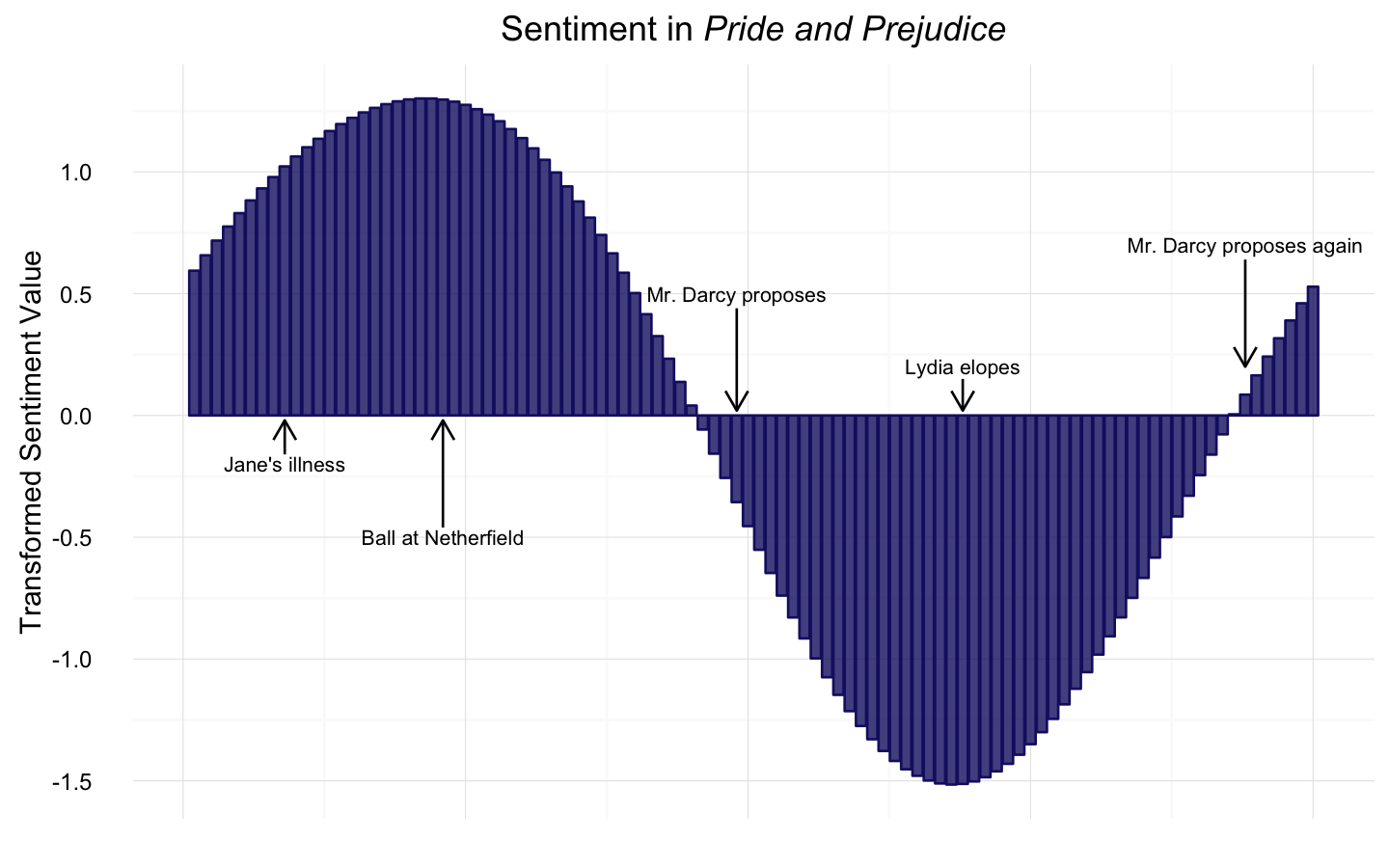

Narrative time runs along the x-axis. Volume II is the shortest of the three parts of the novel. We can see here that the positive sentiment scores are overall much higher than the negative sentiment, which makes sense for Jane Austen’s writing style. We can see some more strongly negative sentiment when Mr. Darcy proposes for the first time and when Lydia elopes. Let’s try visualizing these same data with a bar chart instead of points.

I like certain aspects of both of these styles of plots. What do you think? Is one of these clearer or more appealing to you?

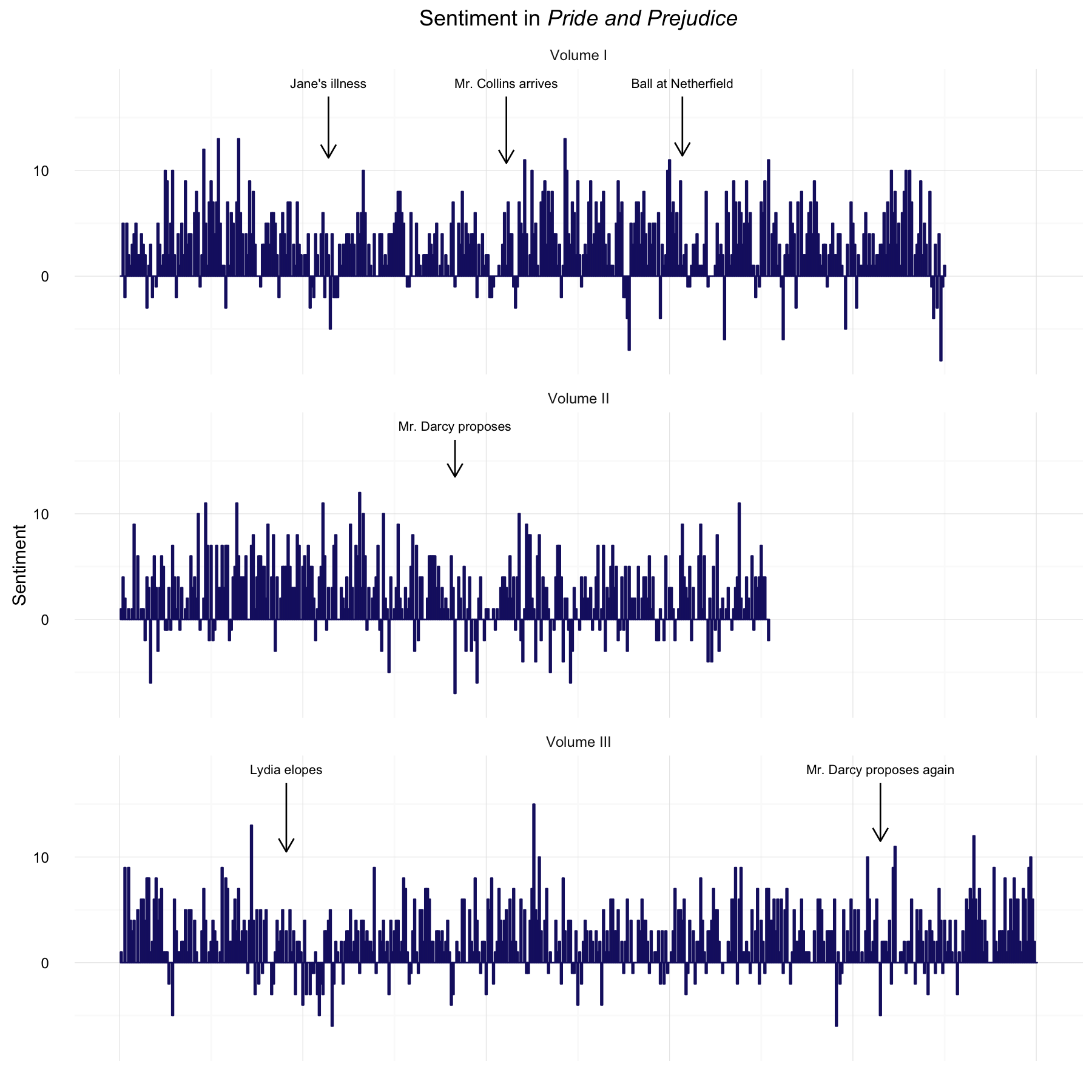

Fourier Transform Time

The previous plots showed both the positive and negative sentiment, but we could also take each chunk of text and assign one value, the positive sentiment minus the negative sentiment for an overall sense of the emotional content of the text. Let’s do that for a new view of the novel’s content.

Now let’s plot this single measure of the sentiment in the novel.

To better see the overall trajectory of the narrative, we can filter and transform these sentiment scores using a low-pass filter Fourier transform. Matthew Jockers, the author of the syuzhet package, describes this in more detail here.

Now, I am a little rusty on the Fourier transform. I haven’t thought much about it since I was a physics undergrad taking an electronics lab; I vaguely remember that I made a square wave by adding up a bunch of sine waves. In the case here with text from a novel, the sentiment scores are the time domain signal. Taking the Fourier transform finds the set of sinusoidal functions to sum up to represent the time domain signal. Thus, the Fourier transform shows us where the narrative sentiment is positive/negative, and the low-pass filter allows us to see the overall structure in the narrative (i.e. low frequency structure) while filtering out high frequency information. We would just have to decide how many components to keep for the low-pass filtering.

This probably jumps out as pretty obvious, but the values have been scaled and centered here to show the narrative shape. The raw sentiment scores were all mostly positive in Pride and Prejudice but the filtered and transformed sentiment scores have been scaled and centered to visualize the overall structure of the narrative. Notice the important events that correspond to the max/min in the transformed and filtered sentiment score. I am just delighted about that. Math! It is the best. I do want to be careful not to overemphasize that result just now, though, because it depends on how many Fourier components we keep during the low-pass filtering. This plot is made by keeping 3 components, the default in the syuzhet package; the shape will look a little different with more small-scale (i.e., higher frequency) structure if we keep 4 or 5 components and the important plot events may not align quite as perfectly with a maximum, for example. I would like to explore this point more.

The FEEEEEEEEEEELINGS

The NRC lexicon includes scores for eight emotions, along with the overall positive and negative sentiment scores. Let’s see how these emotion scores change during the novel. We will need bigger chunks of text to make reasonable looking plots, so let’s go back and concatenate our chunks into bits that are five times larger. (The last chunk will be a bit shorter because it doesn’t come out exactly even.)

Now let’s find the sentiment scores, divide between the three volumes of the novel, and melt for plotting.

Let’s capitalize the names of the emotions for plotting, and also let’s reorder the factor so that more postive emotions are together in the plot and more negative emotions are together in the plot.

For plotting the emotions, let’s make heat maps in the style of Bob Rudis. When I saw him put some examples of these heat maps on Twitter, I just knew that I needed to make some.

Oh, they’re so pretty… We can see the positive emotions are stronger than the negative ones, which is sensible given Austen’s bright, humorous writing style. The negative emotions are stronger in the middle of Volume II when Mr. Darcy proposes for the first time and near the beginning of Volume III when Lydia elopes.

The End

Wow, this was so much fun, although obviously I have outed myself as a super fan. Good thing I have no shame about that whatsoever. The Fourier transformed sentiment values were so interesting, and are perfect for comparing across different texts. I am eager to try that out on some different novels. Boy, I just love that we can do MATH on WORDS; those are two of my very favorite things. The R Markdown file used to make this blog post is available here. I am very happy to hear feedback or questions!

You must allow me to tell you how ardently i admire and love you

«Не was the proudest, most disagreeable man in the world…»

«Дарси был признан одним из самых заносчивых и неприятных людей на свете…»

Уикхэм, воспитавшийся в одном доме с Дарси, заметил как-то, что его гордость в нем была его лучшим другом: она, как ни одно другое чувство, делала его добродетельным человеком:

«It is wonderful», replied Wickham, «for almost all his actions may be traced to pride: and pride has often been his best friend. It has connected him nearer with virtue than any other feeling».

В изображении характера Остен ломает устойчивые литературные традиции. Автор показывает зависимость человеческой психики от материального положения и социальных законов, существующих в обществе.

Так, в романе «Гордость и предубеждение» процесс переосмысления собственных чувств, поступков способствует усмирению гордости героев, относительно мистера Дарси этот процесс сопровождается примирением с обществом. Снисхождение и терпимость к окружающему невежеству, бестактности, сосредоточенной в людях, становится самым мучительным и сложным испытанием для Дарси еще и потому, что он не умеет воспринимать окружающий мир с легкой долей иронии. В этом отношении он намного слабее по волевым качествам, чем Элизабет, чувство юмора которой примиряет ее со многими неприятными обстоятельствами.

Дарси воспринимает жизнь слишком серьезно, он не умеет шутить, поэтому излишне драматизирует события. Впоследствии героиня заражает его своим ироничным отношением к жизни, понимая, что для Дарси это самое оптимальное решение проблемы общения с окружающими. Максимально дозируя собственные шутки, Элизабет приобщает Дарси к окружающему миру, от которого его отдалило воспитание и образование.

Несмотря на свой ум, герой живет в рамках стереотипов, предложенных ему высшим обществом. Еще до знакомства с Элизабет Дарси предубежден против ее общества, предпочитая знакомую ему компанию. Это чувство базируется на мнении героя, что ни внешность, ни поведение мисс Беннет не соответствуют тому идеалу, который придумал для себя Дарси на основании сложившихся в обществе стереотипов:

Though he had detected with a critical eye more than one failure of perfect symmetry in her form, he was forced to acknowledge her figure to be light and pleasing; and in spite of his asserting that her manners were not those of the fashionable world, he was caught by their easy playfulness.

Несмотря на то, что своим придирчивым оком он обнаружил не одно отклонение от идеала в ее наружности, он все же был вынужден признать ее необыкновенно привлекательной. И хотя он утверждал, что поведение Элизабет отличается от принятого в светском обществе, оно подкупало его своей живой непосредственностью.

То есть благодаря принятым в обществе правилам поведения у Дарси заранее складывается предвзятое отношение к Элизабет, что свидетельствует о несамостоятельности мышления героя и его зависимости от мнения света. Под влиянием Элизабет в Дарси происходит процесс ломки стереотипов, вследствие чего меняется его характер.

Именно провинция становится тем место, которое содействует раскрытию лучших, глубинных свойств личности героев. Встреча в Памберли примиряет героев с недостатками друг друга. Она представляется нам кульминационной сценой в развязке интриги. Элизабет должна была увидеть поместье Дарси, обстановку, комнаты, интерьер которых снова доказывает общность вкусов героев. Должна была услышать лестные отзывы о хозяине дома от надежного и незаинтересованного источника, которым стала экономка, знавшая его с малых лет. Увидев Дарси на его земле, Элизабет почувствовала изменившуюся манеру в его поведении. Все это способствовало новому восприятию героиней Дарси: она поняла, что его сословная гордость является результатом духовного одиночества, скрытности и смущения, защитной маской от окружающих. Элизабет убедилась, что внешние проявления гордости, причинившие ей боль, могут быть смягчены иным поведением радушного хозяина. В свою очередь, Дарси, увидев героиню в обществе презентабельных родственников Гардинеров, общение с которыми не умаляло его чести и достоинства и даже наоборот доставляло радость, нашел в себе силы преодолеть свою гордость.

Самохарактеристика героев содержится в прямой диалогической речи. Дарси в разговоре с Элизабет (гл. XI) называет основные черты своего характера: он недостаточно мягок, не умеет забывать пороки и глупость окружающих, не способен расчувствоваться и обидчив.

«I have made no such pretension. I have faults enough, but they are not, I hope, of understanding. My temper I dare not vouch for. It is, I believe, too little yielding—certainly too little for the convenience of the world. I cannot forget the follies and vices of others so soon as I ought, nor their offenses against myself. My feelings are not puffed about with every attempt to move them. My temper would perhaps be called resentful. My good opinion once lost, is lost forever.»

These bitter accusations might have been suppressed, had I, with greater policy, concealed my struggles, and flattered you into the belief of my being impelled by unqualified, unalloyed inclination; by reason, by reflection, by everything. But disguise of every sort is my abhorrence… Could you expect me to rejoice in the inferiority of your connections? To congratulate myself on the hope of relations, whose condition in life is so decidedly beneath my own?

Не мог ли я избежать столь тяжких обвинений, если бы предусмотрительно от вас это скрыл? Если бы я вам польстил, заверив в своей всепоглощающей страсти, которую бы не омрачали противоречия, доводы рассудка или светские условности?

В его речи бессоюзное перечисление однородных предложных дополнений (by reason, by reflection, by everything), употребление условного и сослагательного наклонений (might have been suppressed, had I concealed, could you expect), параллельная конструкция в двух следующих одно за другим вопросительных предложениях (Could you expect me to rejoice… To congratulate myself…) создают эффект нарастания, благодаря которому находят свое выражение его обида и раздражение.

Одной «гранью» языковой личности мистера Дарси является его способность и стремление к эстетизации речевых поступков. Это качество свойственно герою в значительной степени, что выражается в употреблении фразеологизмов, крылатых, а также в активном употреблении разнообразных изобразительно-выразительных средств: эпитетов, метафор, сравнений и т.д.

«I am afraid you have been long desiring my absence, nor have I anything to plead in excuse of my stay, but real, though unavailing concern. Would to Heaven that anything could be either said or done on my part that might offer consolation to such distress! But I will not torment you with vain wishes, which may seem purposely to ask for your thanks. This unfortunate affair will, I fear, prevent my sister’s having the pleasure of seeing you at Pemberley to-day.»

— Вы, должно быть, давно ждете моего ухода. Мне нечем оправдать свою медлительность, разве лишь искренним, хоть и бесплодным сочувствием. Боже, если бы только я мог что-то сделать или высказать для смягчения вашего горя! Но для чего надоедать вам пустыми пожеланиями, как будто добиваясь благодарности?. Боюсь, это печальное событие лишит мою сестру удовольствия видеть вас сегодня в Пемберли?

«You are too generous to trifle with me. If your feelings are still what they were last April, tell me so at once. My affections and wishes are unchanged, but one word from you will silence me on this subject for ever.»

— Вы слишком великодушны, чтобы играть моим сердцем Если ваше отношение ко мне с тех пор, как мы с вами разговаривали в апреле, не изменилось, скажите сразу. Мои чувства и все мои помыслы неизменны. Но вам достаточно произнести слово, и я больше не заговорю о них никогда.

Such I was, from eight to eight and twenty; and such I might still have been but for you, dearest, loveliest Elizabeth!

Таким я был от восьми до двадцати восьми лет. И таким бы я оставался до сих пор, если бы не вы, мой чудеснейший, мой дорогой друг Элизабет!

Любовь Дарси составляет, пожалуй, главную психологическую загадку этого романа. В его чувстве нет ничего рассудочного, хотя он человек, несомненно, рассудительный и проницательный. Как он сам впервые говорит о своей любви:

In vain have I struggled. It will not do. My feelings will not be repressed. You must allow me to tell you how ardently I admire and love you

— Вся моя борьба была тщетной! Ничего не выходит. Я не в силах справиться со своим чувством. Знайте же, что я вами бесконечно очарован и что я вас люблю!

I have been a selfish being all my life, in practice, though not in principle… I was spoiled by my parents, who, though good themselves… allowed, encouraged, almost taught me to be selfish and overbearing, to care for none beyond my own family circle, to think meanly of all the rest of the world, to wish at least to think meanly of their sense and worth compared with my own… You taught me a lesson, hard indeed at first, but most advantageous.

В этом разговоре с Элизабет звучит его самооценка. Повтор слова selfish, выделение курсивом слов right, child, wish, параллельные конструкции (I was taught, I was given, I was spoiled) и перечисления выдают его взволнованное, исповедальное настроение, его благодарность Элизабет, любовь к которой сделала его другим.

Индивидуализация языка персонажей осуществляется писательницей не только с помощью передачи характерного для каждого говорящего содержания, идейного смысла высказываний. Она создается с помощью различных средств: лексического, словарного состава речи, ее синтаксической и стилистической структуры, интонации, введением в речь действующего лица специфических для него особенностей и пр.

Персонажи Остен в большой степени раскрывают свою натуру, в первую очередь, в присущих их речи лексических особенностях. В языке многих действующих лиц нередко даже одно слово, которое они неоднократно употребляют, обнаруживает их духовную сущность.

Роман построен на речевых образах. В произведении отсутствуют прямые описания и авторские комментарии, поэтому герои романа остаются как бы вне поля критики, они предоставлены сами себе. Это самовыражение персонажей через речь становится главным достоинством произведения: оно дает нам представление о том, как говорили и вообще жили люди почти два столетия назад.