Zero to one notes on startups or how to build the future

Zero to one notes on startups or how to build the future

“Zero to One” Summary

Notes on Startups, or How to Build the Future

The book, “Zero to One” by Peter Thiel gave a uniquely impressive perspective on building a startup and the future. Thiel is considered a Shifter according to the characteristic metric constructed by Ray Dalio. Thiel has, over-time, continually proven his ability to perform successfully when executing a new objective. His engineering approach towards business with the lens of a data scientist allows him to both efficiently and effectively execute a strategy.

I challenged myself with finding key takeaways that I could start implementing today with our main business at PlutusX. So, I will outline those in the conclusion section below.

Peter Thiel, for those who are unaware, co-produced what we call PayPal today. He sold the company for a staggering figure. Although, his experience at PayPal led to the development of a security protocol for flagging and detecting fraudulent activity. The software proved extremely promising, so much so that the FBI asked them to develop a similar software similar to their solution for multi-use purposes. After he left the company, he decided to use his network, experience, and newly earned capital to work by starting an investment syndicate and venture capital fund.

Here is a little more on Thiel.

Let’s just dive into it with a quick summary.

Summary

Peter Thiel exposes the evolution of his strategy and philosophy for composing a flourishing startup. He lends lessons acquired from personal experience as a co-founder of PayPal and a venture capital investor that lead him to amass an enormous wealth exceeding a billion thresholds.

Analysis

Here are some key elements for a successful startup or innovating the future that you should consider remembering while reading through the summary.

Chapter 1: The Challenge of the Future

The introduction of the book begins with a favorite question of Thiel’s and that is “What important truth do very few people agree with you on?”

The question thought-provokingly stimulates the interviewee to:

Thiel’s approach for this question stems from a phrase that he used, “Brilliant thinking is rare but courage is in even shorter supply than genius.”

This reminded me of Mark Twain’s “If you find yourself on the side of the majority its time to pause and reflect.”

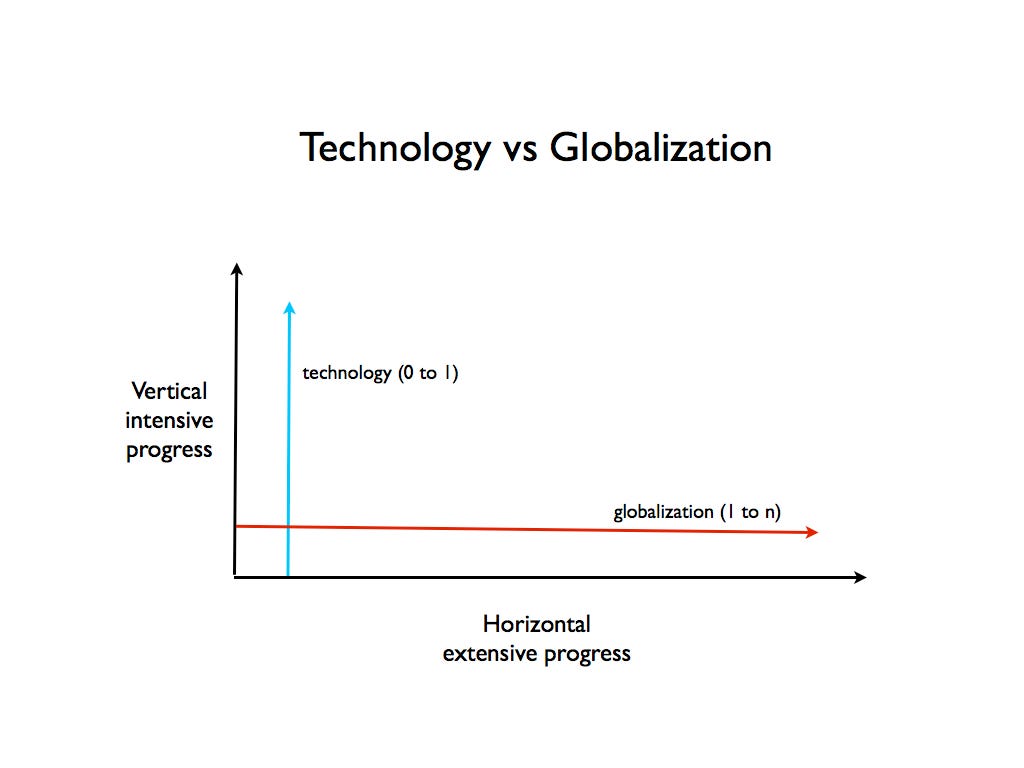

To help better visualize the intangible concept of going from zero to one by building a revolutionary startup or constructing the future he created a graph.

He ends the chapter by frankly asking: “Why Start-ups?” His definition and delineation were very simple.

A start-up is the largest group of people that you can convince of a plan to build a different future.

This definition was far from revolutionary but the concept was interesting none-the-less. The minority group tends to create the grandest scales of cascading movement in society. Check Sivers TED on “Starting a Movement” again.

Chapter 2: Party Like It’s 1999

This chapter begins with an abridgment of the economic landscape of the period in question.

PayPal was created with a goal to create a new digital currency. As the idea evolved the currency became a method for transferring funds via email. The concept was revolutionary. Many merchants would swarm towards the new product as the technology allowed them to receive funds more efficiently in juxtaposition with their former predecessors.

Chapter 3: All Happy Companies Are Different

This particular chapter highlights the similarities (and thus the differences) between happy companies and failing companies.

In Thiel’s opinion ”All happy companies are different: each one earns a monopoly by solving a unique problem. All failed companies are the same: they failed to escape competition.”

Soon after describing the difference between a failing company and a happy one he asked another opposingly difficult question: “ What valuable company is nobody building?”

To Thiel, a Valuable company is the summation of created value in addition to value captured.

The main take away here for aspiring entrepreneurs with the intention of changing the world (hopefully for the better) with your company is that you must create and capture value. You must not build an undifferentiated commodity business (restaurant as we’ll see in the next example).

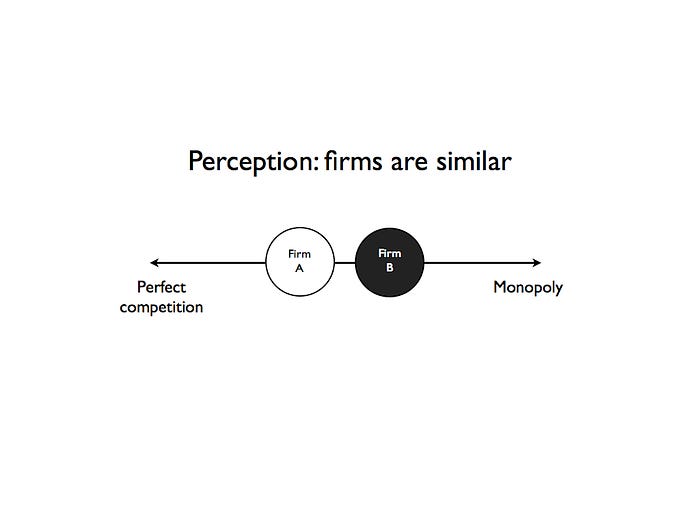

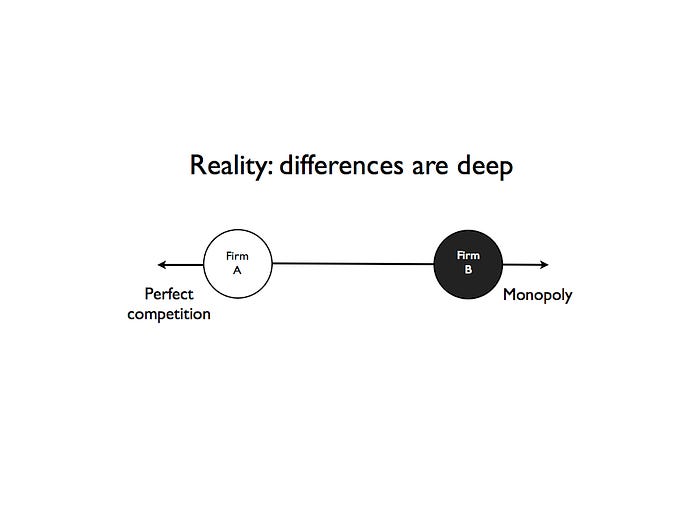

The author attempts to distinguish the differences between a Monopoly (inherently not evil) vs a Perfect Competition (arguably dangerous for businesses vitality). He further explains that both types of companies are trying to disguise themselves as something else as well (usually the opposite of what they are):

Firm A — disguised as a monopoly: Google has a monopoly on search but emphasizes the small share of global online advertising, and other miscellaneous business models.

Firm B — disguised as a perfect competition: A local restaurant tries to find fake differentiators by being the “only British restaurant in Palo Alto” yet they are using inaccurate metrics. The real marker would be “restaurants” not “Restaurant type”

Chapter 4: The Ideology of Competition

Peter describes the business world to be heavily analogous to war. MBAs often attribute their tactful success to the knowledge acquired from books such as “The Art of War”. The analogy is further supplemented by the metaphorical wartime language.

Thiel, perplexed us with another promising question: “ Why do people compete?”

Placing emphasis on the wrong attribute in business (like in war) can lead to the toxic realization that the root problem truly lies in the similarities. For example, while Microsoft and Google were obsessively competing with each other Apple emerged and surpassed both.

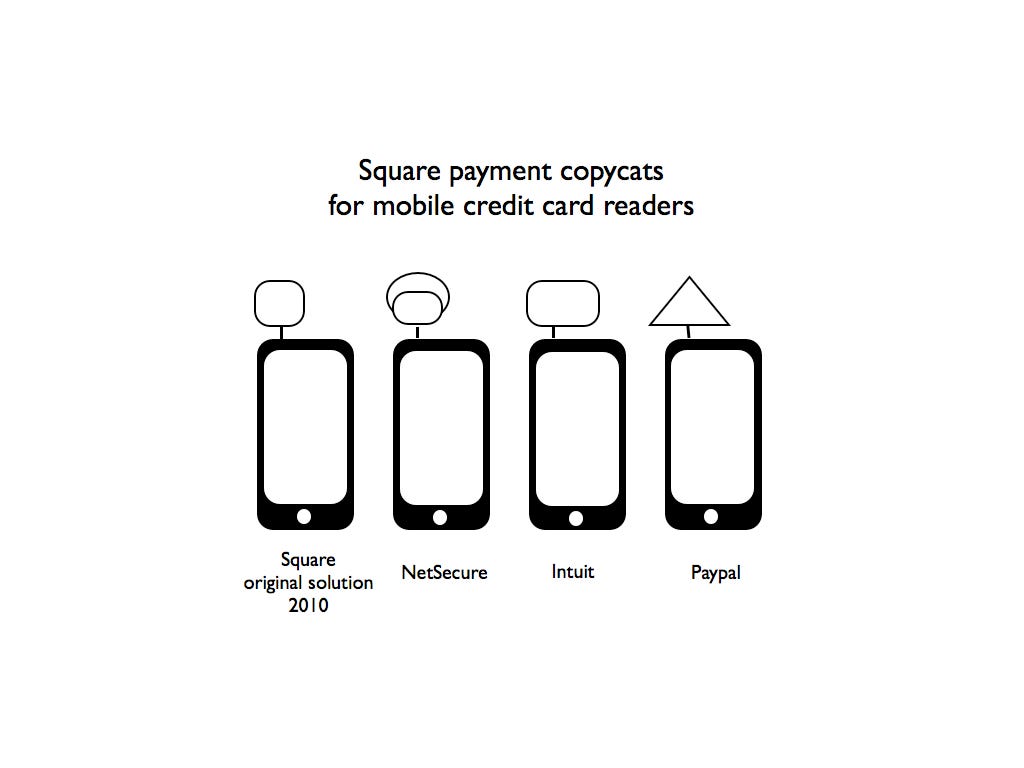

This chapter referenced examples of Square competitors. This illustrated the negative consequences of competition. The act itself is likely to limit vision and focus energy on obsessive hostility. As a result, copying is promoted. : Square copycats.

He also suggested that the best way to resolve conflict (competition) is to merge with your competitors. This is when he decided to work with Musk, despite their initial differences. It’s easier to monopolize the bigger you are or the more targeted your audience.

Chapter 5: Last Mover Advantage*

There are two important time periods in the evolution of an emerging market for creating an effective monopoly; the first mover, and the last mover.

Thiel placed weight on understanding the proper business valuation process (and how to differentiate valid valuations compared to inflated valuations).

The equation for the value of a business today is the value of earnings in the future. Here is an example using the previous definition.

Twitter vs New York Times

Why does a new company surpass a veteran institution?

What defines a monopoly?

How can we build a monopoly?

Chapter 6: You Are NOT a Lottery Ticket

Thiel asks another rhetorical question: Can you control your future?

On the outlandish possibility that you are able to truly know the contents of the future with extreme accuracy then you may be able to control it. However, the reality is that the future is remarkably random and uncertain. So don’t attempt to master it.

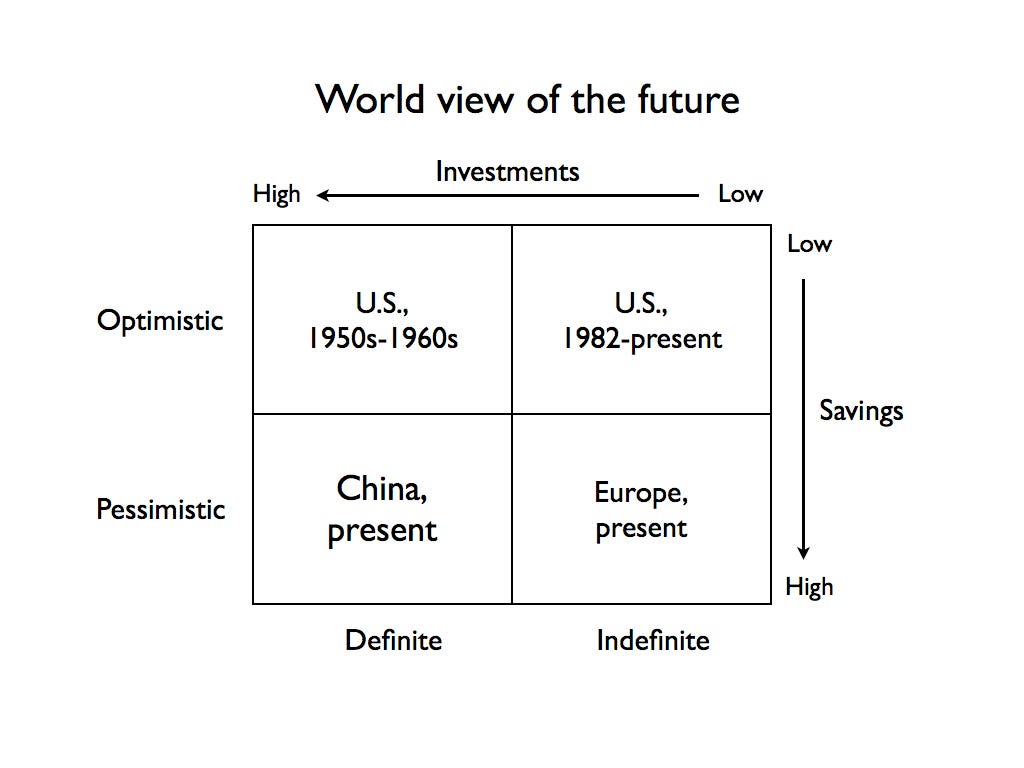

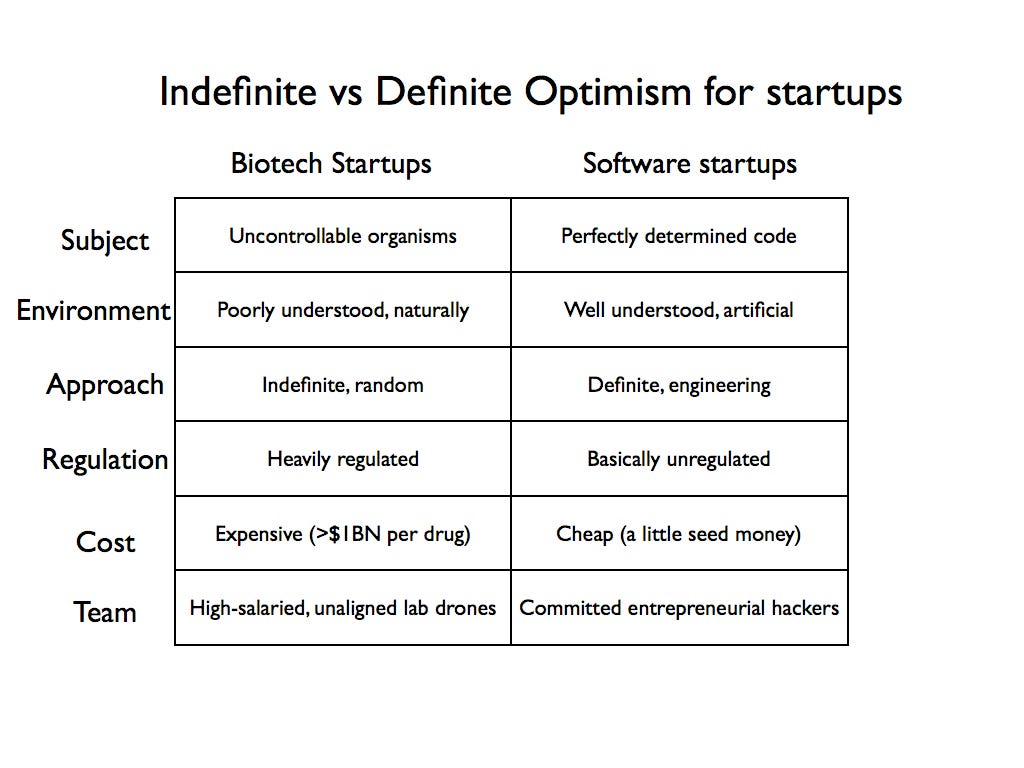

Thiel draws a graph to help illustrate the outcome of the future; better or worse.

Thiel argues that to be successful one (a company) should not practice the development of a mediocre skillset and call it “well-rounded”. Rather focus, like the definite optimist, on one particular interest and dominate, build your monopoly.

Chapter 7: Follow the Money

I won’t bore you down on this. I’ve written on this far too often haha. The 80/20 rule is applicable for startup success as well.

The Pareto principle is evident when observing the money trail. Venture capitalist aims to profit from companies in round series funding. Yet few companies achieve exponential growth. Most fail while few essentially breakeven.

Chapter 8: Secrets

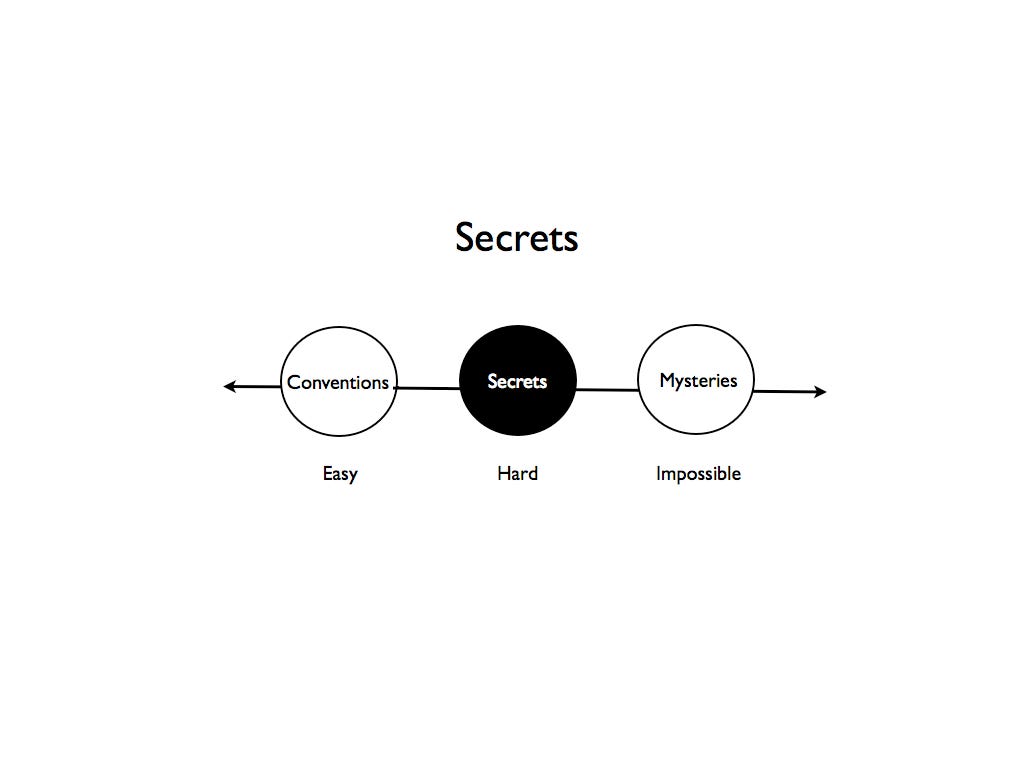

This chapter talks about the elusive topics of hidden secrets that need discovering.

The author uses geography as an illustration to demonstrate the lack of discovery needed, no secrets are left.

He asks another daunting question. What happens when a company stops believing in secrets?

Here is what happens to a company that stops believing in secrets. Let’s examine Hewlett-Packard:

The emphasis of this section is not to have secrets and hide or protect them from others, like some sort of IP. Rather, I believe that Thiel is teaching you that a company conspiring to change the world is a company that will have secrets that once revealed will revolutionize a whole industry. Advancing the movement towards an optimistic future.

Every great business is built around a secret that’s hidden from the outside. Inner workings of Google’s PageRank algorithm, Apple iPhone in 2007, etc…

Chapter 9: Foundations

Distinctively exceptional experiences often are consequences of special identifiable moments in life. Typically the inception of the company is rather significant. Yet, one specific element from the origin is extremely important.

The complimentary personalities and subsequently their skill sets allow for the elixir of success to emerge. Thiel stresses the importance of the co-founder’s compatibility and often overlooks companies with co-founders who do not have prior history beforehand.

He talks about the appeal of having fewer heads on the board. Public companies are mandated to have a minimum amount but Thiel often prefers to have a board of 3.

Thiel uses another incredibly easy to comprehend the analogy for startup culture. You are either on the bus or off the bus. An individual who prioritizes the drawing of salary over the positive contribution to the growth of the value of the company’s equity is an individual who is seeking to extract value otherwise.

The association with the value being given by a cash salary creates short term thinking with an employee. Drawing a high salary as a CEO creates the concept of attachment towards the title as it is correlated with such money (wrong mindset) and also promotes other employees to desire such payment (wrong mindset). The goal is for a company to proportionally give the right amount of equity to promote long term thinking and incentivize the employee to build value with the future in mind and the right amount of cash salary to keep the immediate now satisfied (basic needs + Lil extra).

Chapter 10: The Mechanics of Mafia*

The purpose of this chapter is to create and foster a strong culture within the companies ecosystem. Company culture is similar to a cult, minus the overzealous dogmatism.

I have a lot of thought on building a cult-like company culture given to us by sociologists and evolutional psychologists alike, but this is for another topic. Now we will explore the 4 integral dimensions used to construct an effective company culture.

The goal is to create and foster a strong company culture. Cult participants are usually misinformed fanatics. We want fanatics who are enthusiastic about our problems and mission. You don’t mind others calling you a mafia of sorts either.

Chapter 11: If You Build It, Will They Come?

The distribution mechanism for a startup is immensely crucial to the longevity of the company. Often the trope suggests that a product should sell itself. The marketing is almost negligible. They use companies like Facebook and Google as an example to justify their opinion. However, Thiel argues that the delivery system for a company’s service or good is of equal importance to the product itself.

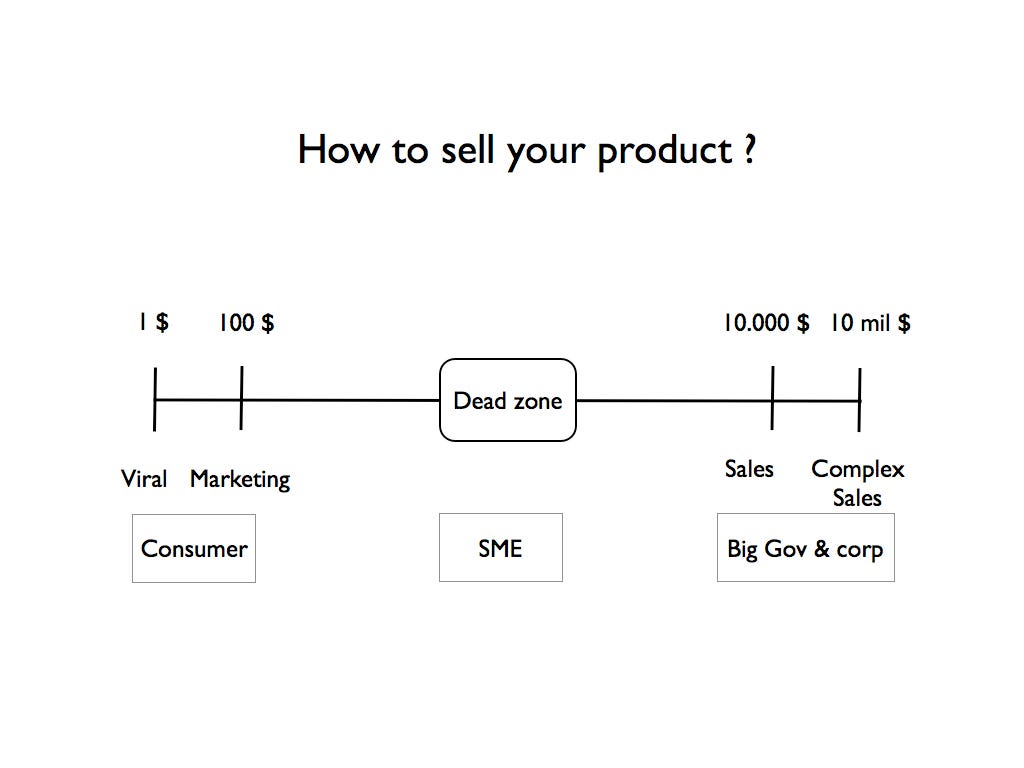

Thiel gives a brief lesson on sales. If the CLV (Customer Lifetime Value) is greater than the CAC (Customer Acquire Cost) then you can learn how to sell with profit. The more expensive the product, the greater the sales costs then the more important to the sale.

Then there are dead zones. The target is usually SMEs (small-medium enterprise, B2B) and they require unique marketing.

Look around, if you don’t see a salesperson, you’re the salesperson

Chapter 12: Man and Machine

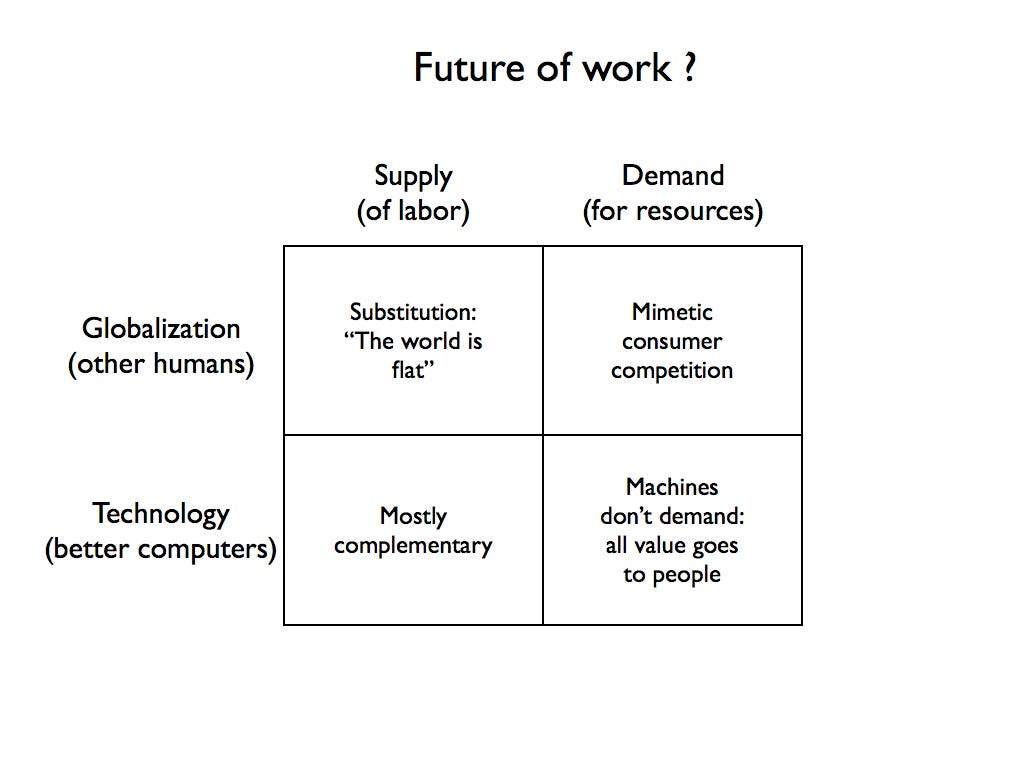

This chapter can be summarized as the computer complimenting humans as a tool of technology vs robots taking over the workforce. There is a great fear that robots will inevitably make humans ineffective. Thiel argues that this is not the case. Instead, he believes that computers will empower the human race rather than make them obsolete.

Thiel offers an example of the complementary relationship computers will have with robots.

This hybrid solution has been used by the FBI for detecting fraud and later inspired the creation of Palantir. The system uses sophisticated AI/ML to help create high-risk and high-probability flag cases to be reviewed by the human analyst in greater detail, “keeping the human in the loop”.

Chapter 13: Seeing green*

If 7 key questions fail to be met in an emerging industry then the eventual demise of the market is inevitable, as suggested by Thiel.

Here are those 7 questions:

These are the 7 constituent of elements that construct a successful company, according to Thiel. If the clean energy sector had the answers to these questions in the mid-2000s circa their death, then the answers were clearly wrong because they ultimately failed. Great lesson to learn what they did so that you do not repeat it.

One again Thiel references his co-founder and friend Musk with Tesla. He states, “One of the few cleantech companies that have found success is Tesla. This is because they got all of the basic issues right. This shows that the problem was never with the idea of cleantech by itself, rather the problem was how most of the cleantech startups ran their firms.”

Many social-driven businesses fail to differentiate themselves from other entities and products and place emphasis on the wrong goal: “To do something good”. Set after the goal to do something different instead (maybe as a monopoly on a smaller scale). The success may come to you similar to it did to Musk with Tesla.

Chapter 14: The Founders Paradox

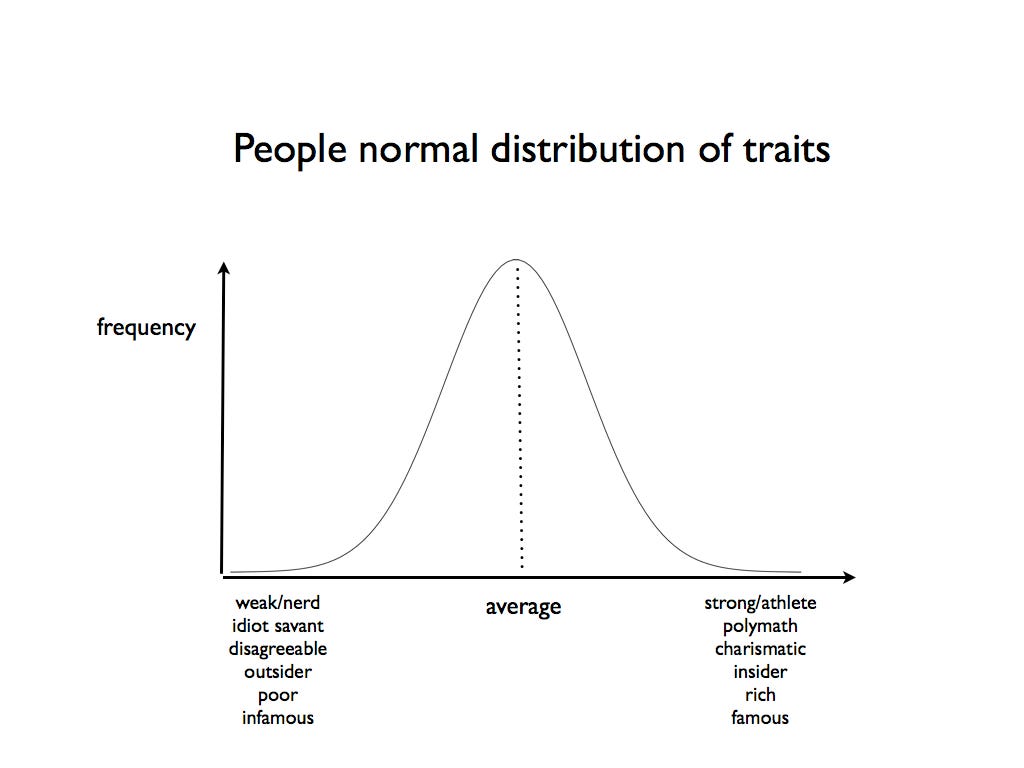

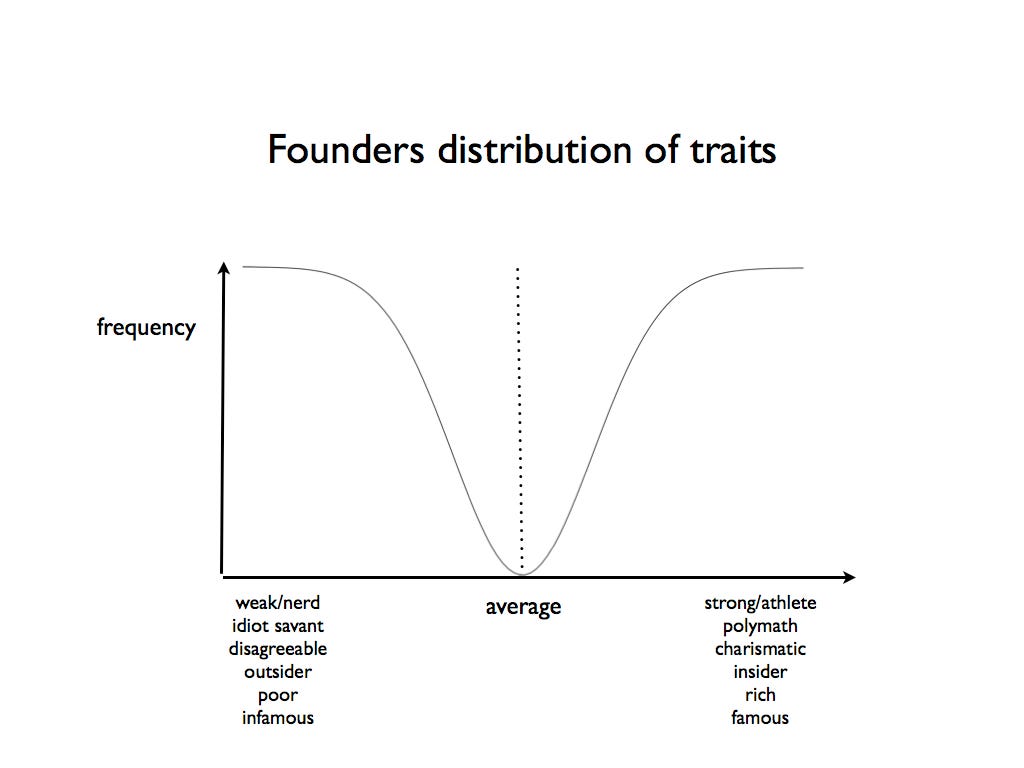

In his last chapter, Thiel draws up some interesting graphs that I don’t necessarily agree with 100%. I believe the underlying message is that successful companies tend to have a concentration of similar personality traits detected inside each founding member.

Here Thiel suggests that the average person falls in the middle of the spectrum and also believes that the inverse of the function is true for the founders. I believe that he is merely suggesting that founders tend to have “extreme” qualities.

I believe that he is also preparing the reader to understand that as an outlier, being placed on the extremities of cultural norms that you are subject to being in a paradoxical state that is you may be loved and hated, rich or poor, and genius or idiot at the same time in the eyes of the public.

He talks roughly about some philosophy about believing strongly in your own abilities. Read some of my other articles on mindset to better understand that portion. Basically, be humble, that’s all.

Conclusion: Stagnation or Singularity?

Debating the contents of the future with high-level accuracy is a feeble task. However, we can anticipate four likely scenarios, as some sort of catch-all.

Four scenarios for the future:

So, effectively we can decide how to shape the future. How will you do your part?

Conclusion

Lesson One: Create a Monopoly

We learned that creating a monopoly is great for business and still can be fair in an open market. Let’s define it and learn how to build one.

What defines a monopoly?

How can we build a monopoly?

Lesson Two: Co-Founders are important

Thiel quantitatively analyses the founders with more scrutiny than the business model or product itself.

The complimentary personalities and subsequently their skill sets allow for the elixir of success to emerge. Thiel stresses the importance of the co-founder’s compatibility and often overlooks companies with co-founders who do not have prior history beforehand.

Defining these components clearly will help mitigate future uproar:

Thiel uses another incredibly easy to comprehend the analogy for startup culture. You are either on the bus or off the bus. An individual who prioritizes the drawing of salary over the positive contribution to the growth of the value of the company’s equity is an individual who is seeking to extract value otherwise.

I believe that he is also preparing the reader to understand that as an outlier, being placed on the extremities of cultural norms that you are subject to being in a paradoxical state that is you may be loved and hated, rich or poor, and genius or idiot at the same time in the eyes of the public. So be humble because you may be celebrated one day and notorious the next.

Lesson Three: Create a Cult

Company culture is similar to a cult, minus the overzealous dogmatism.

I have a lot of thought on building a cult-like company culture given to us by sociologists and evolutional psychologists alike, but this is for another topic. Now we will explore the 4 integral dimensions used to construct an effective company culture.

The goal is to create and foster a strong company culture. Cult participants are usually misinformed fanatics. We want fanatics who are enthusiastic about our problems and mission. You don’t mind others calling you a mafia of sorts either.

Lesson Four: Piece it Together

Let’s create a list of elements needed to create a successful company according to Thiel.

Here are those 7 questions:

These are the 7 constituent of elements that construct a successful company, according to Thiel.

Вышла новая книга «Zero to One» — взгляд Питера Тиля на мир стартапов

За более чем 15 лет предпринимательской и инвестиционной деятельности он накопил немало ценного опыта, и, в своей книге «Zero to One: Notes on Startups, or How to Build the Future», делится им, высказывая множество интересных мыслей и предлагая свой взгляд на методы формирования критического мышления, не привязанного к общепринятым, традиционным взглядам на вещи, а также рассматривает проблемы современных стартапов и предпринимательской среды.

С 16 сентября книга доступна для покупки на английском языке, а 20 октября будет издана на русском. Недавно в сеть была выложена 2 глава книги, под катом мы предлагаем вам собственный вариант ее перевода. Перевод авторского текста выполнил blaarb, все благодарности ему. Сразу хотел бы предупредить, что книга в чем то пересекается с курсом лекций «Стартап» из Стенфорда, но даже тем, кто с ним ознакомился книга будет интересна.

Тиль выступает категорически против повторения предыдущего опыта, противопоставляя ему эффективность собственных, абсолютно новых идей. Он высказывает тезис о том, что конкуренция лишает предпринимателей всякой прибыли и только монополия, основанная на уникальных знаниях и разработках позволяет им вырваться вперед и зарабатывать миллиарды. Билл Гейтс или Ларри Пейдж будущего не станут разрабатывать операционные системы или поисковые алгоритмы, ведь все это уже было придумано и прекрасно работает сейчас. Вместо того, чтобы пытаться отвоевать долю у гигантов рынка, успешные предприниматели будущего сосредоточатся на совершенно уникальных идеях, и будут первыми и единоличными владельцами новых рынков, созданных собственными усилиями.

В «Zero to One» Тиль повествует о качествах и образе мышления, необходимых для того, чтобы преуспеть в современной предпринимательской среде, попутно приводя примеры из собственной практики и обобщая опыт Кремниевой долины за последние 20 лет.

Веселимся как в 99-ом

Ранее, мы задали вопрос: «Есть ли такая истина, которую разделяют с вами лишь немногие?». Непросто дать на него прямой ответ. Легче, наверное, будет начать со вступления: «С какими утверждениями согласны все?». «Безумие единиц — исключение, а безумие целых групп, партий, народов, времен — правило», — писал Ницше (до того как сам потерял рассудок). Сумев распознать популярное заблуждение, вы также сможете найти и правду, которая за ним кроется — правду, которая идет в разрез с общими представлениями.

Подумайте над простым утверждением: компании существуют, чтобы делать деньги, а не терять их. Это должно быть очевидно для любого мыслящего индивида, однако в конце 1990-х нашлось немало людей, которые думали иначе. Они могли охарактеризовать убытки любых размеров как вложение в большое и светлое будущее. Общепринятая мудрость «Новой экономики» рассматривала количество просмотров страниц в качестве более достоверной и дальновидной финансовой метрики, вместо чего-то такого прозаичного, как прибыль.

И только когда мы оглядываемся назад, в прошлое, становится понятно, что общепринятые взгляды были предвзятыми и неверными. Мы распознаем «пузыри» только когда те уже лопнули, однако вызванные ими негативные изменения никуда не исчезают вместе с ними. «Интернет-пузырь» 90-х был крупнейшим за последние 80 лет и уроки, которые мы из него извлекли, деформировали современное восприятие технологий, практически полностью его определив. Первое, что надо сделать, для того, чтобы научится думать непредвзято — пересмотреть наши знания о прошлом.

Короткая история 90-x

У 1990-х хорошая репутация. Мы склонны вспоминать их как десятилетие процветания и оптимизма, которое завершилось Интернет-бумом и обвалом. Те годы, однако, не были такими радостными, как мы о них ностальгируем. Мы уже давно забыли о глобальных процессах которые сопровождали 18 месяцев безумия в конце того десятилетия.

90-е начались со вспышки эйфории: в ноябре 1989 года пала Берлинская стена. Радость продолжалась не долго. К середине 1990-ого, США испытывали рецессию. Формально спад закончился в марте 91-ого, однако восстановление проходило медленно, а уровень безработицы продолжал расти до июля 92-ого. Производственному сектору так и не удалось в полной мере восстановиться. Переход к экономике сферы услуг был продолжительным и болезненным.

Период с 1992 по 1994 был тревожным для всех. Фотографии мертвых американских солдат в Могадишу регулярно появлялись в телевизионных новостях. Беспокойства по поводу глобализации и конкурентоспособности усилились вместе с оттоком рабочих мест в Мексику. Эти скрытые пессимистичные настроения стоили Бушу-старшему президентского поста, позволив Россу Перо получить почти 20% голосов избирателей на выборах в 92-ом — лучший результат для стороннего кандидата со времен Теодора Рузвельта в 1912. А общее восхищение Нирваной, гранжем и героином, отражало что угодно, только не надежду или уверенность.

Кремниевая долина также производила вялое впечатление. Япония, казалось, побеждала в полупроводниковой войне. Интернету еще только предстояло начать свой путь, отчасти потому что его коммерческое использование было запрещено до конца 1992 года, а отчасти — из-за отсутствия удобных браузеров. Тот факт, что когда я пришел в Стэнфорд в 1985 году, самым популярным предметом была экономика, а не информатика, говорит сам за себя. Большинство людей в кампусе считало технологический сектор чем-то специфическим, если не сказать, недалеким.

Интернет все изменил. Официальный релиз браузера Mosaic состоялся в ноябре 1993 года, предоставив обычным пользователям способ выйти онлайн. Компания Mosaic превратилась в Netscape, которая, в свою очередь, выпустила в 1994 году браузер Navigator. Он так быстро набрал популярность — с 20% рынка браузеров в январе 1995 до 80% меньше чем за год, что Netscape была способна выйти на IPO в августе 95-ого, даже еще не будучи прибыльной. В течении пяти месяцев, ее стоимость взлетела с 28 до 174 долларов за акцию. Гремели и другие технологические компании. Yahoo! вышла на IPO в апреле 96-ого и была оценена в 848 миллионов долларов. За ней последовала Amazon c 438 миллионами. К весне 98-ого, акции всех этих компании выросли более чем в четыре раза. Скептики ставили под вопрос показатели доходов и прибыли, которые превышали аналогичные цифры для любой не-интернет компании.

Можно понять, почему они пришли к этому неуместному заключению. В декабре 96-ого, более чем за 3 года до того, как пузырь лопнул, председатель ФРС Алан Гринспен предупредил, что «нерациональное изобилие», возможно, «чрезмерно завышает ценность активов». Технологические инвесторы были слишком щедры, однако сказать наверняка, что они поступали нерационально нельзя: слишком уж легко забывается тот факт, что у всего остального мира дела тогда шли не очень хорошо.

В июле 1997 разразился азиатский финансовый кризис. Коррумпированность капитализма в странах юго-восточной Азии и крупный внешний долг поставили экономики Таиланда, Индонезии и Южной Кореи на колени. За ним, в августе 98-ого последовал кризис рубля, когда Россия, ослабленная постоянным бюджетным дефицитом, провела девальвацию своей валюты и объявила дефолт. Беспокойство американских инвесторов по поводу нации у которой есть 10000 ядерных боеголовок, но нет денег выросло — промышленный индекс Доу-Джонса обвалился больше чем на 10% всего за несколько дней.

Люди беспокоились не напрасно. Рублевый кризис запустил цепную реакцию, которая уничтожила Long‐Term Capital Management, американский хедж-фонд с большой долей заемных средств в обращении. LCTM умудрился потерять 4.6 миллиардов долларов во второй половине 1998, имея на тот момент обязательства на сумму более 100 миллиардов. ФРС вмешалась, проведя крупную операцию по выкупу его активов и резко снизив ставку кредитования для предотвращения экономической катастрофы. В Европе дела шли немногим лучше. В январе 1997 был принят в оборот евро, встреченный равнодушным скептецизмом. В первый день торгов он вырос до отметки 1.19 долларов, медленно падая до 0.83 долларов в течении двух последующих лет. В середине 2000-х, центральным банкам «Большой семерки» пришлось искусственно поддерживать его курс многомиллиардными долларовыми интервенциями.

Начавшаяся в сентябре 1998 года, мимолетная мания доткомов проходила в мире, где кажется уже ничто не работало. Старая экономика не могла справиться с вызовами глобализации и в такой момент должно было появится что-то, что сработало бы и сработать оно должно было по-крупному. Нужно было поддержать веру в то, что будущее вообще может стать лучше, и поэтому, рассуждая от противного, все решили, что «Новая экономика» Интернета будет единственным выходом из ситуации.

Мания: Сентябрь 1998-ого – Март 2000-ого

Мания доткомов была кратковременным, но ярким явлением — 18 месяцев безумия, с сентября 1998 года по март 2000. Ее можно назвать золотой лихорадкой Кремниевой долины: деньги были повсюду. Хватало и через чур богатых, нередко, сомнительных личностей, гонявшихся за ними. Каждую неделю десятки стартапов соревновались друг с другом, организовывая вечеринки в честь своего «запуска» (вечеринки в честь «открытия компании» были гораздо более редким явлением). Фиктивные миллионеры ужинали, выписывая чеки на трехзначные суммы, пытаясь расплатиться долями акций своих стартапов и иногда это даже срабатывало. Толпы людей покидали свои хорошо оплачиваемые рабочие места для того, чтобы основать свой стартап или присоединиться к существующему.

Я знал одного сорокалетнего студента-аспиранта, у которого было шесть разных компаний в 1999 году. (Обычно это странно — быть 40-летним аспирантом. Открыть полдюжины компаний одновременно тоже считается странным, однако в поздние 90-е люди вполне могли поверить в то, что это сочетание принесет им успех.) Нам следовало еще тогда понять, что мания не могла продолжаться долго, поскольку самые «успешные» компании избрали своего рода анти-бизнес модель, при которой чем больше компания росла, тем больше денег она теряла. Трудно, однако винить людей в желании танцевать, пока играет музыка. Иррациональные поступки были нормой, учитывая тот факт, что добавление «.com» к своему имени могло удвоить вашу стоимость за ночь.

PayPal мания

Когда я управлял PayPal в конце 1999 года, я чуть не потерял голову от страха. Дело не в том, что я не верил в нашу компанию, просто у меня складывалось впечатление, будто люди в Кремниевой долине готовы были поверить во что угодно. Куда не посмотри, компании появлялись, выходили на IPO, и тут же продавались с настораживающей простотой. Один мой знакомый рассказывал, как планировал провести IPO прямо из дома, еще даже не зарегистрировав свою компанию, и это не казалось ему странным. В такого рода обстановке разумное поведение выглядело слишком эксцентрично.

К осени 99-го наш продукт по переводу платежей с помощью электронной почты работал как следует. Любой желающий мог войти на наш сайт и с легкостью перевести деньги. Однако нам не хватало клиентов, а темпы роста расходов значительно опережали доходы. Для того, чтобы PayPal заработал, нам нужно было привлечь по крайней мере миллион пользователей. Давать рекламу было слишком неэффективно с точки зрения затрат. Многообещающие сделки с крупными банками провалились одна за другой. Поэтому мы решили платить людям за регистрацию.

Мы давали новым клиентам 10$ за регистрацию и еще 10$ каждый раз, когда они приводили друзей. Это дало нам сотни тысяч новых клиентов и экспоненциальный рост. Разумеется, эта стратегия приобретения клиентов не была жизнеспособной: модель, при которой вы платите людям, чтобы они стали вашими клиентами, означает экспоненциальный рост не только доходов, но и расходов. Сумасшедшие траты были вполне обычной ситуацией для Долины в то время, однако мы полагали, что наши огромные затраты были оправданны: с учетом большой базы пользователей, у PayPal появился реальный способ стать прибыльным — при помощи введения комиссий за каждую проводимую клиентами транзакцию.

Мы знали, что для достижения этой цели нам потребуется больше средств. Мы также понимали, что бум закончится и поскольку мы не ожидали, что у инвесторов появится вера в то, что наша миссия уцелеет во время грядущей катастрофы, мы быстро перешли к сбору средств, пока такая возможность еще была. 16 февраля 2000 года, в Wall Street Journal появилась хвалебная история про наш вирусный рост, которая высказывала предположение, что PayPal стоил 500 миллионов долларов.

В следующем месяце, нам удалось получить финансирование на сумму 100 миллионов. Наш основной инвестор тогда принял сделанные на коленке расчеты Journal за авторитетную информацию. Другие инвесторы также спешили. Одна южнокорейская фирма отправила нам 5 миллионов, без предварительного обсуждения сделки или подписи каких-либо документов. Когда я попытался их вернуть, они совершенно не хотели сообщать, куда их следовало отправлять.

Раунд финансирования, прошедший в марте 2000-го, дал нам достаточно времени для того, чтобы превратить PayPal в успешный сервис. Стоило нам только закрыть сделку, как пузырь лопнул.

Уроки, которые мы усвоили

Cause they say 2,000 zero zero party over, oops! Out of time! So tonight I’m gonna party like it’s 1999!

— Принс, песня «1999»

Индекс NASDAQ достиг пиковой отметки в 5,048 пунктов в середине марта 2000 года, после чего обвалился до 3,321 в апреле. К тому времени, как в октябре 2002 он достиг нижнего предела в 1,114 пунктов, страна уже давно истолковала крах рынка как, своего рода, божью кару, за весь технологический оптимизм 90-ых. Эпоха изобилия и надежды, переименованная в эпоху безумной алчности, была признана завершенной.

Мы научились относится к будущему как к чему-то, принципиально неопределенному, а людей которые осмеливались строить планы не на кварталы, а на годы вперед, мы просто не воспринимали всерьез. Веру в светлое будущее теперь обеспечивала глобализация, а не технологии. Переход с «bricks на clicks» 1 не оправдал возлагаемых на него надежд и инвесторы вернулись обратно к bricks (жилищному строительству) и БРИКС (глобализации). В результате лопнул еще один пузырь, на этот раз — в сфере недвижимости.

1 — игра слов, bricks — крипичи, clicks — клики (прим. переводчика)

Предприниматели, которым пришлось заплатить за крах Кремниевой долины, извлекли из кризиса доткомов 4 важных урока, которые по сей день лежат в основе делового мышления:

1. Двигайтесь вперед постепенно

Пузырь раздулся благодаря грандиозным замыслам, а значит, им не следует потакать. Мы стали с подозрениям относится к людям, утверждающим, что они способны сделать что-то великое, а тех, кто захотел изменить мир, просили быть поскромнее в своих желаниях. Небольшие, постепенные шаги — единственный безопасный путь к развитию.

2. Будьте рациональны и адаптивны

Каждой компании следует быть «рациональной», что в данном случае означает «незапланированной». Вам не следует знать, что будет делать ваш бизнес в будущем. Планирование — слишком самонадеянное занятие, ограничивающее вашу возможность меняться. Вместо этого, следует предпринимать попытки, «проводить итерации» и смотреть на предпринимательство как на серию экспериментов, которые не придерживаются определенного видения.

3. Совершенствуйтесь, используя конкуренцию

Не пытайтесь преждевременно создавать новый рынок. Единственный способ быть уверенным в том, что вы занимаетесь настоящим бизнесом — начать с уже существующих клиентов, поэтому вам следует создавать свою компанию, делая лучше легко узнаваемые продукты, ранее предложенные успешными конкурентами.

4. Сосредоточьтесь на продукте, а не продажах

Недостаточно продавать ваш продукт при помощи одной только рекламы или продавцов: технология — это прежде всего разработка продукта, а не его распространение. Реклама времен пузыря, очевидно, оказалась пустой тратой средств, поэтому устойчивый рост может основываться только на сарафанном радио и репостах.

Эти уроки стали догмами мира стартапов, а тот, кто предпочитает их игнорировать, по всеобщему убеждению, навлекает на себя божью кару, которая настигла технологии во время великого краха 2000 года. И тем не менее, более справедливыми, вероятно, являются обратные принципы:

Технологии по прежнему нужны нам. Возможно нам даже пригодится немного высокомерия и изобилия в духе 1999-го для их создания. Для того, чтобы построить следующее поколение компаний, мы должны отбросить догмы, появившиеся в результате краха. Это не означает, что противоположные по смыслу идеи автоматически становятся истиной: нельзя избежать безумия толпы, слепо отвергая ее догмы. Вместо этого, спросите себя: насколько сильно ошибки прошлого повлияли на ваши знания о бизнесе сегодня? Мыслить в разрез с общепринятым мнением не значит делать все наоборот, это значит — думать своей головой.

Zero to One: Notes on Startups, or How to Build the Future

What you need in a quick read…

To inspire the next big star of the business world.

Preface: Zero to One

Every moment in business happens only once.

If you are copying, you’re likely not learning. It’s easier to copy than to make something new. Doing what we already know takes us from 1 to n, adding more of something familiar. Every time we create something new, we go from 0 to 1. Creation is singular and the result is something fresh and strange.

Unless they invest in creating new things, American companies will fail in the future no matter how big their profits remain today.

Today’s “best practices” lead to dead ends; the best paths are new and untried.

Searching for a new path might seem like hoping for a miracle, but humans are distinguished from other species by our ability to work miracles. We call these miracles technology. Technology is miraculous because it allows us to do more with less. By creating new technologies, we rewrite the plan of the world.

Zero to One is about how to build companies that create new things.

This book offers no formula for success. The paradox of teaching entrepreneurship is that such a formula necessarily cannot exist; because every innovation is new and unique, no authority can prescribe in concrete terms how to be innovative. Indeed, the single most powerful pattern I have noticed is that successful people find value in unexpected places, and they do this by thinking about business from first principles instead of formulas.

The Challenge of the Future

When I interview someone for a job, I like to ask: “What important truth do very few people agree with you on?”

Brilliant thinking is rare, but courage is in even shorter supply than genius.

A good answer takes the following form: “Most people believe in x, but the truth is the opposite of x.”

No one can predict the future exactly, but we know two things: it’s going to be different, and it must be rooted in today’s world. Most answers to the contrarian question are different ways of seeing the present; good answers are as close as we can come to looking into the future.

When we think about the future, we hope for a future of progress. Horizontal or extensive progress means copying things that work — going from 1 to n. Vertical or intensive progress means doing new things — going from 0 to 1. At the macro level, horizontal progress is globalization. For vertical progress, it’s technology.

Any new and better way of doing things is technology.

Spreading old ways to create wealth around the world will result in devastation, not riches. In a world of scarce resources, globalization without new technology is unsustainable. We have inherited a richer society than any previous generation would have been able to imagine.

Our challenge is to both imagine and create the new technologies that can make this century more peaceful and prosperous than the last.

New technology tends to come from new ventures — startups or small groups of people bound together by a sense of mission. It’s hard to develop new things in big organizations and it’s even harder to do by yourself. In the most dysfunctional organizations, signaling that work is being done becomes a better strategy for career advancement than actually doing work (if this describes your company, you should quit now).

A startup is the largest group of people you can convince of a plan to build a different future. A new company’s most important strength is new thinking: even more important than nimbleness, small size affords space to think. This book is about questions you must ask and answer to succeed in the business of doing new things. What follows is not a manual or a record of knowledge, but an exercise in thinking. That is what a startup has to do: question received ideas and rethink business from scratch.

Party Like It’s 1999

Our contrarian question — What important truth do very few people agree with you on? — is difficult to answer directly. It may be easier to start with: what does everybody agree on? If you can identify a delusional popular belief, you can find what lies hidden behind it: the contrarian truth.

Conventional beliefs only ever come to appear arbitrary and wrong in retrospect; whenever one collapses, we call the old belief a bubble.

The first step to thinking clearly is to question what we think we know about the past.

As Alan Greenspan warned, “irrational exuberance might unduly escale values.”

When I was running PayPal in late 1999, I was scared out of my wits — not because I didn’t believe in our company, but because it seemed like everyone else in the Valley was ready to believe anything at all. Everywhere I looked, people were starting and flipping companies with alarming casualness. In this environment, acting sanely began to seem eccentric.

The NASDAQ reached its peak in the middle of March 2000 and then crashed in the middle of April. By the time it bottomed out in October 2002, the country had long since interpreted the market’s collapse as a kind of divine judgment against the technological optimism of the ’90s. The era of cornucopian hope was relabeled as an era of crazed greed and declared to be definitely over. Everyone learned to treat the future as fundamentally indefinite and to dismiss as an extremist anyone with plans big enough to be measured in years instead of quarters. Globalization replaced technology as the hope for the future. Since the ’90s migration “from bricks to clicks” didn’t work as hoped, investors went back to bricks (housing) and BRICs (globalization). The result was another bubble, this time in real estate.

Four big lessons from the dot-com crash:

These lessons have become dogma in the startup world and yet the opposite principles are probably more correct:

There was a bubble in technology. The late ’90s was a time of hubris: people believed in going from 0 to 1. Too few startups were actually getting there and many never went beyond talking about it. People understood that we had no choice but to find ways to do more with less. The market high of March 2000 was a peak of insanity; less obvious, but more important, it was also a peak of clarity. People looked far into the future, saw how much valuable new technology we would need to get there safely, and judged themselves capable of creating it.

We still need new technology and we may even need some 1999-style hubris and exuberance to get it. To build the next generation of companies, we must abandon the dogmas created after the crash. That doesn’t mean the opposite ideas are automatically true: you can’t escape the madness of crowds by dogmatically rejecting them. Instead ask yourself: how much of what you know about business is shaped by mistaken reactions to past mistakes? The most contrarian thing of all is not to oppose the crowd but to think for yourself.

All Happy Companies Are Different

The business version of our contrarian question is: what valuable company is nobody building? Your company could create a lot of value without becoming very valuable itself. Creating value is not enough — you also need to capture some of the value you create.

If you want to create and capture lasting value don’t build an undifferentiated commodity business.

Monopolists and competitors add to market confusion with their bias and incentivization to bend the truth. Monopolists lie to protect themselves. They know that bragging about their great monopoly invites audits, scrutiny, and attacks. They tend to do whatever they can to conceal their monopoly — usually by exaggerating the power of their (nonexistent) competition. Competitors lie by trying to convince people that they are exceptional instead of seriously considering whether that’s true.

Non-monopolists exaggerate their distinction by defining their market as the intersection of various smaller markets.

Monopolists, by contrast, disguise their monopoly by framing their market as the union of several large markets.

In business, money is either an important thing or it is everything. Monopolists can afford to think about things other than making money; non-monopolists can’t.

A monopoly is good for everyone on the inside, but what about everyone on the outside? Outsized profits do come at the expense of society, right out of customers’ wallets, but monopolies only deserve a bad reputation if nothing changes. In a static world, a monopolist is just a rent collector. The world we live in is dynamic, though, and it’s possible to invent new and better things. Creative monopolists give customers more choices by adding entirely new categories of abundance to the world. Creative monopolies aren’t just good for the rest of society; they’re powerful engines for making it better. Even the government knows this: that’s why one of its departments works hard to create monopolies (by granting patents to new inventions) even though another part hunts them down (by prosecuting antitrust cases). It’s possible to question whether anyone should really be awarded a legally enforceable monopoly simply for having been the first to think of something like a mobile software design. It’s clear that something like Apple’s monopoly profits from designing, producing, and marketing the iPhone were the reward for creating greater abundance, not artificial scarcity. The dynamism of new monopolies explains why old monopolies don’t strangle innovation. Apple’s mobile computing reduced Microsoft’s operating system dominance. IBM’s hardware monopoly was overtaken by Microsoft’s software monopoly. If the tendency of monopoly businesses were to hold back progress, they would be dangerous and we’d be right to oppose them, but history shows better monopoly businesses replacing incumbents.

Economists see individuals and businesses as interchangeable atoms, not as unique creators. Their theories describe an equilibrium state of perfect competition because that’s what’s easy to model, not because it represents the best of business. In business, equilibrium means stasis, and stasis means death.

Every business is successful exactly to the extent that it does something others cannot.

As Tolstoy said, “All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” Business is the opposite. All happy companies are different: each one earns a monopoly by solving a unique problem. All failed companies are the same: they fail to escape competition.

The Ideology of Competition

Creative monopoly means new products that benefit everybody and sustainable profits for the creator. Competition means slim profits, less meaningful differentiation, and a struggle for survival. Why do people believe competition is healthy? Competition is an ideology — the ideology that pervades our society and distorts our thinking. We trap ourselves in competition even though the more we compete, the less we gain.

Our educational system drives and reflects our obsession with competition. Grades allow measurement of each student’s competitiveness. Pupils with the highest marks receive status and credentials. We teach most young people the same subjects in mostly the same ways, irrespective of individual talents and preferences. Students who don’t learn best by sitting still at a desk are made to feel inferior, while children who excel on conventional measures like tests and assignments end up defining their identities in terms of this weirdly contrived academic parallel reality. It gets worse at high levels. Higher education is the place where people who had big plans get stuck in fierce rivalries with equally smart peers over conventional careers. For the privilege of being turned into conformists, students and families pay hundreds of thousands of dollars in skyrocketing tuition that outpaces inflation. Why are we doing this to ourselves?

Professors downplay the cutthroat culture of academia, but managers never tire of comparing business to war. War metaphors invade our everyday business language. We use headhunters to build up a sales force that will enable us to take a captive market and make a killing. It’s really competition, not business, that is like war: allegedly necessary, supposedly valiant, but ultimately destructive. According to Marx, people fight because they are different. According to Shakespeare, all combatants look more or less alike. It’s not all clear why they should be fighting, since they have nothing to fight about.

The hazards of imitative competition may explain why individuals with social ineptitude seem to be at an advantage in Silicon Valley. If you’re less sensitive to social cues, you’re less likely to do the same things as everyone else around you. If you’re interested in making things, you’ll be less afraid to pursue those activities single-mindedly and thereby become incredibly good at them. Then when you apply your skills, you’re less likely to give up your own convictions, which can save you from getting caught up on crowds competing for obvious prizes.

Competition can make people hallucinate opportunities where none exist. Winning is better than losing, but everybody loses when the war isn’t one worth fighting. Rivalries can be weird and distracting too. Too much time can be spent worrying about competition. Sometimes you do have to fight. Where that’s true, you fight to win. There is no middle ground: either don’t throw any punches or strike hard and end it quickly.

Last Mover Advantage

Escaping competition will give you a monopoly, but even a monopoly is only a great business if it can endure in the future. A great business is defined by its ability to generate cash flows in the future. Most of a tech company’s value will come at least 10 to 15 years in the future. Value can exist far in the future. For a company to be valuable, it must grow and endure. Many entrepreneurs focus on only short-term growth. Growth is easy to measure, but durability isn’t. If you focus on near-term growth above all else, you miss the most important question you should be asking: will this business still be around a decade from now? Numbers alone won’t tell you the answer. You must think critically about the qualitative characteristics of your business.

Every monopoly is unique, but they usually share some combination of proprietary technology, network effects, economies of scale, and branding. Proprietary technology should be at least 10 times better than its closest substitute to lead to a real monopolistic advantage. Anything less than an order of magnitude better will probably be perceived as a marginal improvement and will be harder to sell, especially in an already crowded market. The clearest way to make a 10x improvement is to invent something completely new. Network effects make a product more useful as more people use it. Network effects can be powerful, but you will never reap them unless your product is valuable to its very first users when the network is small. Network effects businesses must start with small markets. Costs of creating a product can be spread out over ever greater quantities of sales. Software companies enjoy dramatic economies of scale because the marginal cost of producing another copy of the product is close to zero. A good startup should have the potential for great scale built into its first design. Creating a strong brand is a powerful way to claim a monopoly. It’s largely about consumer experience and perception. Beginning with the brand rather than substance is dangerous. No technology company can be built on branding alone.

Brand, scale, network effects, and technology combine to define a monopoly. To get them to work, you need to choose your market carefully and expand deliberately.

Every startup should start with a very small market. It is much easier to reach a few thousand people who really need your product than to try to compete for the attention of millions of scattered individuals. Once you create and dominate a niche market, then you should gradually expand into related and slightly broader markets. The whole world doesn’t need to adopt a product at once, it won’t. The product should work well for intense interest groups.

The most successful companies make the core progression to first dominate a specific niche and then scale to adjacent markets as a part of their founding narrative.

Disruption can attract attention and if you truly want to make something new, the act of creation is far more important than the old industries that might not like what you create. As you craft a plan to expand to adjacent markets, don’t disrupt: avoid competition as much as possible.

You’ve probably heard of “first mover advantage.” If you’re the first entrant into a market, you can capture significant share while others scramble to get started. Moving first is a tactic, not a goal. What really matters is generating cash flows in the future. Being the first mover doesn’t do you any good if someone else comes along and unseats you. It’s better to be the last mover — to make the last great development in a specific market and enjoy years of monopoly profits. The way to do that is to dominate a small niche and scale up from there, toward your ambitious long-term vision. Business is like chess, as Grandmaster Capablanca said, “to succeed, you must study the endgame before everything else.”

You Are Not A Lottery Ticket

The most contentious question in business is whether success comes from luck or skill.

Malcolm Gladwell declares success as a “patchwork of lucky breaks and arbitrary advantages.”

Warren Buffett considers himself a “member of the lucky club” and a “winner of the lottery.”

Jeff Bezos attributes Amazon’s success to an “incredible planetary alignment with luck, good timing, and brains.”

Bill Gates claims that he was “lucky to be born with certain skills.”

Perhaps they are being strategically humble, but regardless, serial entrepreneurship calls into question our tendency to explain success as the product of chance. If success was a matter of luck, surely serial entrepreneurs like Steve Jobs, Jack Dorsey, and Elon Musk would exist.

As Jack Dorsey said, “success is never accidental.”

Luck is something to be mastered, dominated, and controlled by doing what you can and not focusing on what you can’t. As Roald Amundsen wrote, “victory awaits him who has everything in order — luck, people call it.”

It the future a matter of chance or design?

You can expect the future to take a definite form or you can treat it as hazily uncertain. If you treat it as definite, it makes sense to understand it in advance and work to shape it. If you expect an indefinite future ruled by randomness, you’ll give up on trying to master it.

Indefinite attitudes to the future explain what’s most dysfunctional in our world today. Process trumps substance. When people lack concrete plans to carry out, they use formal rules to assemble a portfolio of various options. Americans in school today are encouraged to start hoarding “extracurricular activities.” Ambitious students compete to appear omnipotent. By the time a student goes to college, s/he spent a decade curating a diverse resume to prepare for an unknowable future. Come what may — s/he was ready for nothing in particular.

A definite view favors firm convictions. Instead of pursuing many-sided mediocrity and calling it “well-roundedness,” a definite person determines the one best thing to do and does it. S/he strives to be great at something substantive — to be a monopoly of one. This is not what young people do today because people around them are losing faith or have already lost faith in a definite world. No one gets into Stanford by excelling at just one thing, unless it happens to involving catching or throwing a leather ball.

You can expect the future to be better or worse than the present. Optimists welcome the future and pessimists fear it. Combining these possibilities yields four views:

Finance epitomizes indefinite thinking. It’s the only way to make money when you have no idea how to create wealth. Think of what happens when successful entrepreneurs sell their company. What do they do with the money? In a financialized world the founders don’t know what to do with it so they give it to a large bank. The bankers don’t know what to do with it so they diversify by spreading it across a portfolio of institutional investors. Institutional investors don’t know what to do with their managed capital, so they diversify by amassing a portfolio of stocks. Companies try to increase their share price by generating free cash flows. If they do, they issue dividends or buy back shares and the cycle repeats. At no point does anyone in the chain know what to do with money in the real economy. In an indefinite world, people prefer unlimited optionality, money is more valuable than anything you could possibly do with it. Only in a definite future is money a means to an end, not the end itself.

Arguing over process has become a way to endlessly defer making concrete plans for a better future.

Scientists seek to harness the power of chance through pharmaceutical companies searching through combinations of molecular compounds at random hoping to find a hit.

U.S. companies are letting cash pile up on their balance sheets without investing in new projects because they don’t have any concrete plans for the future.

Progress without planning is what we call evolution.

Even in Silicon Valley, the buzzwords call for lean startups that can adapt and evolve to an ever-changing environment. Would-be entrepreneurs are told that nothing can be known in advance and we’re supposed to listen to what customers say, making nothing more than a minimum viable product to iterate our way to success. Leanness is a methodology, not a goal. Making small changes to things that already exist might lead you to a local maximum, but it won’t help you find the global maximum. Iteration without a bold plan won’t take you from 0 to 1. Why should you expect your own business to succeed without a plan to make it happen? Darwinism might be a fine theory in other contexts, but in startups, intelligent design works best.

Every great entrepreneur is first and foremost a designer. The greatest thing Steve Jobs designed was his business. Jobs saw that you can change the world through careful planning, not by listening to focus group feedback or copying others’ successes.

Planning explains the difficulty of valuing private companies. When a big company makes an offer to acquire a successful startup, it almost always offers too much or too little. Founders only sell when they have no more concrete visions for the company, in which case the acquirer probably overpaid. Definite founders with robust plans don’t sell, which means the offer wasn’t high enough. A business with a good definite plan will always be underrated in a world where people see the future as random.

We have to find our way back to a definite future. The Western world needs nothing short of a cultural revolution to do it.

Follow the Money

Money makes money.

Albert Einstein stated that compound interest was “the eighth wonder of the world.”

Never underestimate exponential growth and the power law. They define our surroundings so completely that we usually don’t even see them.

The power law becomes visible when you follow the money: in venture capital, where investors try to profit from exponential growth in early-stage companies, a few companies attain exponentially greater value than all others.

The big question is when takeoff will happen. For most funds, the answer is never. Expecting venture returns to be normally distributed is wrong. Assuming this blind pattern, investors assemble a diversified portfolio and hope that winners counterbalance losers. This “spray and pray” approach usually flops with no hits at all. Venture returns do not follow a normal distribution. They follow a power law. A small handful of companies radically outperform all the others. If you focus on diversification instead of single-minded pursuit of the very few companies that can become overwhelmingly valuable, you’ll miss the rare companies in the first place.

The biggest secret in venture capital is that the best investment in a successful fund equals or outperforms the entire rest of the fund combined.

Every single company in a good venture portfolio must have the potential to succeed at vast scale.

The power law is not just important to investors; it’s important to everybody because everybody is an investor. An entrepreneur makes a major investment just by spending time working on a startup. Every entrepreneur must think about whether his/her company is going to succeed and become valuable. Every individual is unavoidably an investor. When you choose a career you act on your belief that the kind of work you do will be valuable decades from now.

The most common answer to the question of future value is a diversified portfolio: “Don’t put all your eggs in one basket,” we’re told. Even the best investors have a portfolio, but investors who understand the power law make as few investments as possible. Folk wisdom and financial convention says that the more you dabble, the more you are supposed to have hedged against the uncertainty of the future. Life is not a portfolio, though. You cannot diversify yourself. You cannot run dozens of companies at the same time and hope one of them works out well. An individual cannot diversify his or herself by keeping dozens of equally possible careers in ready reserve. Our schools teach homogenized, generic knowledge. Everybody who passes through the American school systems learns not to think in power law terms. Model students obsessively hedge their futures by assembling a suite of exotic and minor skills. Universities have huge catalogs of departments of knowledge to reassure you that it doesn’t matter what you do, as long as you do it well. That is false. It does matter what you do. You should focus relentlessly on something you’re good at doing. Before that, you must think hard about whether it will be valuable in the future.

The power law means that differences between companies will dwarf the differences in roles inside companies.

If you start you own company, remember the power law to operate it well. The most important things are singular. One market will likely be better than all others. One distribution strategy usually dominates all others.

Secrets

Every one of today’s most famous and familiar ideas was once unknown and unsuspected. A conventional truth can be important, but it’s essential to learn elementary mathematics, for example — but it won’t give you an edge. Every correct answer to “what valuable company is nobody building?” is a secret. It’s something important and unknown. Something hard to do, but doable. If there are many secrets left in the world, there a likely many more world-changing companies yet to be started.

In order to be happy, every individual needs to have goals whose attainment requires effort and needs to succeed in attaining at some some of his/her goals. Human goals can be satisfied with minimal effort and serious effort. There are some goals that cannot be satisfied no matter how much effort one makes.

Four social trends have conspired to root out belief in secrets.

You need brilliance to succeed, but you also need faith in secrets. If you think something hard is impossible, you’ll never even start trying to achieve it. Belief in secrets is an effective truth. The actual truth is that there are many more secrets left to find, but they will yield only to relentless searchers. We will never learn any of these secrets unless we demand to know them and force ourselves to look.

There are two kinds of secrets: secrets of nature and secrets about people. Natural secrets exist all around us; to find them, one must study some undiscovered aspect of the physical world. Secrets about people are different: they are things that people don’t know about themselves or things they hide because they don’t want other to know. When thinking about what kind of company to build, there are two distinct questions to ask: What secrets is nature not telling you? What secrets are people not telling you?

It’s easy to assume that natural secrets are the most important, The people who look for them can sound intimidatingly authoritative. This is why PhDs can be notoriously difficult to work with — they know the most fundamental truths, they can think they know all truths. Secrets about people are relatively underappreciated. Maybe because you don’t need dozens of years of higher education to ask the questions that uncover them.

The best place to look for secrets is where no one else is looking. Are the any fields that matter but haven’t been standardized and institutionalized?

If you find a secret, you face a choice: Do you tell anyone? Or do you keep it to yourself?

It’s rarely a good idea to tell everybody everything that you know. Who do you tell? Whoever you need to and no more. Every great business is built around a secret that’s hidden from the outside. A great company is a conspiracy to change the world. When you share your secret, the recipient becomes a fellow conspirator.

Take the hidden paths.

Foundations

A startup messed up at its foundation cannot be fixed. Beginnings are special. As with the cosmos, the very laws of physics are different at beginnings. Fundamental questions can be opened for debate that are hard to change. Companies are like countries in this way. Bad decisions early on are hard to correct after. As a founder, your first job is to get the first things right. You cannot build a great company on a flawed foundation.

When I consider investing in a startup, I study the founding teams. Technical abilities and complementary skill sets matter, but how well the founders know each other and how well they work together matter just as much. You need good people who get along, but you also need a structure to help keep everyone aligned for the long term.

To anticipate likely sources of misalignment in any company, it’s useful to distinguish between three concepts:

A typical startup allocates ownership among founders, employees, and investors. The managers and employees who operate the company enjoy possession. A board of directors, usually comprising founders and investors, exercises control.

Distributing these functions among different people makes sense, but it also multiplies opportunities for misalignment.

Early-stage startups are small enough that founders usually have both ownership and possession. Most conflicts in a startup erupt between ownership and control — that is, between founders and investors on the board.

In the boardroom, less is more. The smaller the board, the easier it is for the directors to communicate, to reach consensus, and to exercise effective oversight. However, effectiveness means that a small board can forcefully oppose management in conflicts.

A board of three is ideal. Your board should never exceed five people, unless your company is publicly held.

Startups don’t need to pay high salaries because they can offer something better: part ownership of the company itself. Equity is the one form of compensation that can effectively orient people toward creating value in the future. Allocate it very carefully. Giving everyone equal shares is usually a mistake: everyone has different talents and responsibilities as well as different opportunity costs. Equal amounts will seem arbitrary and unfair from the start. Granting different amounts up front is just as sure to seem unfair though.

Since it’s impossible to achieve perfect fairness when distributing ownership, founders would do well to keep the details secret. Most people don’t want equity at all. People find it unattractive. It’s not liquid like cash. It’s tied to one specific company and if that company doesn’t succeed, it’s worthless. Equity is powerful because of these limitations. Anyone who prefers owning part of your company to being paid in cash reveals a preference for the long term and a commitment to increasing your company’s value in the future.

Bob Dylan said that “he who is not busy being born is busy dying.”

The most valuable kind of company maintains an openness to invention that is most characteristic of beginnings. This leads to a less obvious understanding of founding: it lasts as long as a company is creating new things. It ends when creation stops. If you get the founding moments right, you can do more than create a valuable company, you can steer its distant future toward the creation of new things.

The Mechanics of Mafia

What would the ideal company culture look like? Employees should love their work. They should enjoy going to the office so much that formal business hours become obsolete and nobody watches the clock. The workspace should be open, not cubicled and workers should feel at home. Without substance perks don’t work. No company has a culture; every company is a culture. A startup is a team of people on a mission, and a good culture is just what that looks like on the inside.

Why work with a group of people who don’t even like each other? Since time is your most valuable asset, it’s odd to spend it working with people who don’t envision any long-term future together. If you can’t count durable relationships among the fruits of your time at work, you haven’t invested your time well.

With PayPal, we set out to hire people who would enjoy working together. They had to be talented, but even more than that they had to be excited about working specifically with us.

Recruiting is a core competency for any company. It should never be outsourced. Talented people don’t need to work for you; they have plenty of options. You’ll attract the employees you need if you can explain why your mission is compelling: not why it’s important in general, but why you’re doing something important that no one else is going to get done. A great mission is not enough. You should be able to explain why your company is a unique match for him/her personally. Don’t fight the perk war.

From outside the company, everyone inside your company should be different in the same way — a tribe of like-minded people fiercely devoted to the company’s mission. Every new hire should be equally obsessed.

On the inside, every individual should be sharply distinguished by his/her work.

When assigning responsibilities to employees in a startup, you could start by treating it as a simple optimization problem to efficiently match talents with tasks. Startups have to move fast, so individual roles can’t remain static for long. The best thing I did as a manager at PayPal was make every person in the company responsible for one unique thing and evaluate on that one thing. Defining roles reduced conflict. Internal peace enables a startup to survive.

The best startups might be considered slightly less extreme kinds of cults. The biggest difference is that cults tend to be fanatically wrong about something important. People at a successful startup are fanatically right about something those outside it have missed.

If You Build It, Will They Come?

Even though sales is everywhere, most people underrate its importance. Customers will not just come because you built it. Advertising matters because it works. Advertising doesn’t exist to make you buy a product right away. It exists to embed subtle impressions that will drive sales later.

All salesmen are actors: their priority is persuasion, not sincerity. If you don’t know any grandmasters, it’s not because you haven’t encountered them, but rather because their art is hidden in plain sight. Sales works best when hidden.

The grail is a product great enough that it sells itself, but the best product doesn’t always win. If you’ve invented something new but you haven’t invented an effective way to sell it, you have a bad business no matter how good the product.

Superior sales and distribution by itself can create a monopoly, even with no product differentiation. No matter how strong your product — even if it easily fits into already established habits and anybody who tries it immediately likes it — you must still support it with a strong distribution plan. Two metrics set the limits for effective distribution — Customer Lifetime Value and Customer Acquisition Cost.

A good enterprise sales strategy starts small. A new customer might agree to become your biggest customer, but they’ll rarely be comfortable signing a deal completely out of scale with what you’ve sold before. Once you have a pool of reference customers who are successfully using your product, then you can begin the long and methodical work of hustling toward ever bigger deals.

Marketing and advertising work for relatively low-priced products that have mass appeal but lack any method of viral distribution. A product is viral if its core functionality encourages users to invite their friends to become users too. The is where you want to get the most valuable users first; the smaller niche market and enthusiastic early adopters.

Poor sales rather than bad product is the most common cause of failure. If you can get just one distribution channel to work, you have a great business. If you try for several but don’t nail one, you’re finished.

Your company needs to sell more than its product. You must sell your company to employees and investors. Selling your company to the media is a necessary part of selling it to everyone else. You should never assume that people will admire your company without a public relations strategy. Press can help attract investors and employees. Any prospective employee worth hiring will do his/her own diligence; what s/he finds or doesn’t find when s/he googles you will be critical to the success of your company.

Man and Machine

The most valuable businesses of coming decades will be built by entrepreneurs who seek to empower people rather than try to make them obsolete. Computers are tools, not rivals. Computers complementing humans is the way to build a great business.

The most valuable companies in the future won’t ask what problems can be solved with computers alone. Instead they’ll ask: how can computers help humans solve hard problems?

Once computers can answer all our questions, perhaps they’ll ask why they should remain subservient to us at all.

Seeing Green

The questions every business must answer.

Any great business plan must address each of these questions.

Notes from Peter Thiel’s Zero to One, or how to build the future

I read Zero to One over the Christmas weekend. It made me want to dramatically increase pace of change personally and professionally. My synapses were firing constantly.

Here are some of my key takeaways and thoughts.

Good ideas that look like bad ideas

Zero to One is about building companies that change the world. The title refers to the creation of something unique and original — when 0 becomes 1. Most new enterprises are not focused on going from zero to one, but from 1 to n — in other words, not creating unique businesses that invent or redefine industries (Uber, ebay, Google, Airbnb, Tesla are all examples of this), but enter competitive markets & deliver incremental improvements.

Starting companies that revolutionize industries requires original, contrarian thinking. If this thinking wasn’t contrarian, it would already be a feature of the industry & the domain of bigger companies with greater resources. Chris Dixon refers to this phenomenon as ‘good ideas that look like bad ideas’ (its a good talk and worth watching). Thiel frames this as a question he asks founders: What important truth do very few people agree with you on? Value is created in the grey space that consensus hasn’t yet reached.

When we started onefinestay, not many people agreed that homes would provide a suitable alternative for the 5* hotel customer. This would be our important truth.

But most new companies aren’t pursuing new ideas, and most VCs are pouring money into these companies. As a result we have lots of startups not changing the world, and lots of VCs with pedestrian returns.

How did we get here?

Thiel makes a convincing argument that our current startup climate is the result of a multi-decade hangover following boom and bust of the late 90s. 20 years ago, lots of new ideas were being introduced to the market — some good, many not so good. At this time, capital started flooding the market, too.

When the bubble burst, much of the capital remained (VC fund cycles are 10 years — performance is far less liquid than the Nasdaq) but was seeking a new breed of ‘risk averse’ startups — companies that:

However, as history has shown for the true innovators, as well as the VCs who have backed contrarian businesses over the past decade, it’s far better and more valuable to be bold (see Power-Law returns explanation by Marc Andreesen, also well covered in this book).

Rather than think about the future in terms of fixed number of years, Theil thinks about the future in terms of speed of progress. At the current speed of technological change, a very different ‘future’ might be 10 years away. For the best part of human existence, a different future was hundreds or thousands of years away.

For individuals on a career track, the resulting question to ask yourself is: how can you capitalize on the speed of change a fast moving environments can offer, and actualize your career ambitions much quicker? As Thiel says in Tools of Titans:

If you are planning on doing something with your life, if you have a 1o-year plan on how to get there, you should ask: why can’t you do this in 6 months?

Competition is like war — allegedly necessary, supposedly valiant, but ultimately destructive.

The trouble for companies entering a competitive market — or one where substitutes are readily available (e.g. an Indian food vs Chinese food restaurant) — is that supply and demand are efficient forces, which means profits trend to zero. Creating lasting value is predicated creating profit, which is predicated on building a meaningfully differentiated business.

Instead, Thiel suggests companies focus on micro markets, create a dominant position, and use this momentum to whip out to pursue a broader opportunity. Some examples are:

This incubation period allows the business to iron out its kinks and ripen before entering the big leagues. It’s the sequel to Kevin Kelly’s 1,000 true fans idea.

This idea applies not only to companies at formation, but as they continue to evolve (for example, the battle for the desktop and mobile environment between Microsoft and Google 10 years ago proved so distracting that Apple stepped in and ran the table).

Other applications of the competition vs monopoly paradigm

Competition breeds conformity — this starts from a young age, where getting the ‘A’ requires a certain set of behaviors, and continues often well into people’s careers. The cycle may never end. That ‘A’ leads to a top college which leads to a top grad school which leads to a career at a top law firm or bank. In order to follow this track, many people’s unique qualities are sanded down and replaced by well-roundedness. There’s nothing wrong with consciously choosing a certain career track if you’re passionate about the work, but its easy to sleepwalk your way into a career that isn’t personally fulfilling and doesn’t create impact.

Rather, people should strive to be really great at one thing, and use that to make an impact on the world. At onefinestay, a degree of well-roundedness is important but ultimately we try and hire for spikes. Its the one great thing that allows every new hire to have the future potential to transform our organization.