How to create makefile

How to create makefile

Makefile для самых маленьких

Не очень строгий перевод материала mrbook.org/tutorials/make Мне в свое время очень не хватило подобной методички для понимания базовых вещей о make. Думаю, будет хоть кому-нибудь интересно. Хотя эта технология и отмирает, но все равно используется в очень многих проектах. Кармы на хаб «Переводы» не хватило, как только появится возможность — добавлю и туда. Добавил в Переводы. Если есть ошибки в оформлении, то прошу указать на них. Буду исправлять.

Статья будет интересная прежде всего изучающим программирование на C/C++ в UNIX-подобных системах от самых корней, без использования IDE.

Компилировать проект ручками — занятие весьма утомительное, особенно когда исходных файлов становится больше одного, и для каждого из них надо каждый раз набивать команды компиляции и линковки. Но не все так плохо. Сейчас мы будем учиться создавать и использовать Мейкфайлы. Makefile — это набор инструкций для программы make, которая помогает собирать программный проект буквально в одно касание.

Для практики понадобится создать микроскопический проект а-ля Hello World из четырех файлов в одном каталоге:

Все скопом можно скачать отсюда

Автор использовал язык C++, знать который совсем не обязательно, и компилятор g++ из gcc. Любой другой компилятор скорее всего тоже подойдет. Файлы слегка подправлены, чтобы собирались gcc 4.7.1

Программа make

Процесс сборки

Компилятор берет файлы с исходным кодом и получает из них объектные файлы. Затем линковщик берет объектные файлы и получает из них исполняемый файл. Сборка = компиляция + линковка.

Компиляция руками

Самый простой Мейкфайл

В нем должны быть такие части:

Для нашего примера мейкфайл будет выглядеть так:

Использование зависимостей

Использовать несколько целей в одном мейкфайле полезно для больших проектов. Это связано с тем, что при изменении одного файла не понадобится пересобирать весь проект, а можно будет обойтись пересборкой только измененной части. Пример:

Это надо сохранить под именем Makefile-2 все в том же каталоге

Использование переменных и комментариев

Переменные широко используются в мейкфайлах. Например, это удобный способ учесть возможность того, что проект будут собирать другим компилятором или с другими опциями.

Что делать дальше

После этого краткого инструктажа уже можно пробовать создавать простые мейкфайлы самостоятельно. Дальше надо читать серьезные учебники и руководства. Как финальный аккорд можно попробовать самостоятельно разобрать и осознать такой универсальный мейкфайл, который можно в два касания адаптировать под практически любой проект:

lifeissweetgood/makefile-tutorial

Use Git or checkout with SVN using the web URL.

Work fast with our official CLI. Learn more.

Launching GitHub Desktop

If nothing happens, download GitHub Desktop and try again.

Launching GitHub Desktop

If nothing happens, download GitHub Desktop and try again.

Launching Xcode

If nothing happens, download Xcode and try again.

Launching Visual Studio Code

Your codespace will open once ready.

There was a problem preparing your codespace, please try again.

Latest commit

Git stats

Files

Failed to load latest commit information.

README.md

A tutorial on Makefiles (Based on tutorial written here)

Let’s Demystify Makefiles!

This tutorial explains what Makefiles are, how they are useful and shows how to write your own from scratch. To see how Makefiles work «in action,» clone the source code on the master branch and compile the simple C project. There are different versions of the same Makefile with varying degrees of complexity. To compile each, run the following commands:

To run the simple C program, do:

To run a different version of the Makefile, do:

What is a makefile?

Rules usually take the form of:

What is the syntax of a Makefile?

Makefiles incorporate bash scripting with its own special syntax to indicate targets and variables.

You can run bash commands like

Makefiles also have special macros for indicating variables:

You can also introduce your own macros like:

The ultimate make and Makefile resource: GNU make docs

Просто о make

Меня всегда привлекал минимализм. Идея о том, что одна вещь должна выполнять одну функцию, но при этом выполнять ее как можно лучше, вылилась в создание UNIX. И хотя UNIX давно уже нельзя назвать простой системой, да и минимализм в ней узреть не так то просто, ее можно считать наглядным примером количество- качественной трансформации множества простых и понятных вещей в одну весьма непростую и не прозрачную. В своем развитии make прошел примерно такой же путь: простота и ясность, с ростом масштабов, превратилась в жуткого монстра (вспомните свои ощущения, когда впервые открыли мэйкфайл).

Мое упорное игнорирование make в течении долгого времени, было обусловлено удобством используемых IDE, и нежеланием разбираться в этом ‘пережитке прошлого’ (по сути — ленью). Однако, все эти надоедливые кнопочки, менюшки ит.п. атрибуты всевозможных студий, заставили меня искать альтернативу тому методу работы, который я практиковал до сих пор. Нет, я не стал гуру make, но полученных мною знаний вполне достаточно для моих небольших проектов. Данная статья предназначена для тех, кто так же как и я еще совсем недавно, желают вырваться из уютного оконного рабства в аскетичный, но свободный мир шелла.

Make- основные сведения

make — утилита предназначенная для автоматизации преобразования файлов из одной формы в другую. Правила преобразования задаются в скрипте с именем Makefile, который должен находиться в корне рабочей директории проекта. Сам скрипт состоит из набора правил, которые в свою очередь описываются:

1) целями (то, что данное правило делает);

2) реквизитами (то, что необходимо для выполнения правила и получения целей);

3) командами (выполняющими данные преобразования).

В общем виде синтаксис makefile можно представить так:

То есть, правило make это ответы на три вопроса:

Несложно заметить что процессы трансляции и компиляции очень красиво ложатся на эту схему:

Простейший Makefile

Предположим, у нас имеется программа, состоящая всего из одного файла:

Для его компиляции достаточно очень простого мэйкфайла:

Компиляция из множества исходников

Предположим, что у нас имеется программа, состоящая из 2 файлов:

main.c

Makefile, выполняющий компиляцию этой программы может выглядеть так:

Он вполне работоспособен, однако имеет один значительный недостаток: какой — раскроем далее.

Инкрементная компиляция

Представим, что наша программа состоит из десятка- другого исходных файлов. Мы вносим изменения в один из них, и хотим ее пересобрать. Использование подхода описанного в предыдущем примере приведет к тому, что все без исключения исходные файлы будут снова скомпилированы, что негативно скажется на времени перекомпиляции. Решение — разделить компиляцию на два этапа: этап трансляции и этап линковки.

Теперь, после изменения одного из исходных файлов, достаточно произвести его трансляцию и линковку всех объектных файлов. При этом мы пропускаем этап трансляции не затронутых изменениями реквизитов, что сокращает время компиляции в целом. Такой подход называется инкрементной компиляцией. Для ее поддержки make сопоставляет время изменения целей и их реквизитов (используя данные файловой системы), благодаря чему самостоятельно решает какие правила следует выполнить, а какие можно просто проигнорировать:

Попробуйте собрать этот проект. Для его сборки необходимо явно указать цель, т.е. дать команду make hello.

После- измените любой из исходных файлов и соберите его снова. Обратите внимание на то, что во время второй компиляции, транслироваться будет только измененный файл.

После запуска make попытается сразу получить цель hello, но для ее создания необходимы файлы main.o и hello.o, которых пока еще нет. Поэтому выполнение правила будет отложено и make станет искать правила, описывающие получение недостающих реквизитов. Как только все реквизиты будут получены, make вернется к выполнению отложенной цели. Отсюда следует, что make выполняет правила рекурсивно.

Фиктивные цели

На самом деле, в качестве make целей могут выступать не только реальные файлы. Все, кому приходилось собирать программы из исходных кодов должны быть знакомы с двумя стандартными в мире UNIX командами:

Командой make производят компиляцию программы, командой make install — установку. Такой подход весьма удобен, поскольку все необходимое для сборки и развертывания приложения в целевой системе включено в один файл (забудем на время о скрипте configure). Обратите внимание на то, что в первом случае мы не указываем цель, а во втором целью является вовсе не создание файла install, а процесс установки приложения в систему. Проделывать такие фокусы нам позволяют так называемые фиктивные (phony) цели. Вот краткий список стандартных целей:

Теперь мы можем собрать нашу программу, произвести ее инсталлцию/деинсталляцию, а так же очистить рабочий каталог, используя для этого стандартные make цели.

Обратите внимание на то, что в цели all не указаны команды; все что ей нужно — получить реквизит hello. Зная о рекурсивной природе make, не сложно предположить как будет работать этот скрипт. Так же следует обратить особое внимание на то, что если файл hello уже имеется (остался после предыдущей компиляции) и его реквизиты не были изменены, то команда make ничего не станет пересобирать. Это классические грабли make. Так например, изменив заголовочный файл, случайно не включенный в список реквизитов, можно получить долгие часы головной боли. Поэтому, чтобы гарантированно полностью пересобрать проект, нужно предварительно очистить рабочий каталог:

Для выполнения целей install/uninstall вам потребуются использовать sudo.

Переменные

Все те, кто знакомы с правилом DRY (Don’t repeat yourself), наверняка уже заметили неладное, а именно — наш Makefile содержит большое число повторяющихся фрагментов, что может привести к путанице при последующих попытках его расширить или изменить. В императивных языках для этих целей у нас имеются переменные и константы; make тоже располагает подобными средствами. Переменные в make представляют собой именованные строки и определяются очень просто:

Существует негласное правило, согласно которому следует именовать переменные в верхнем регистре, например:

Ниже представлен мэйкфайл, использующий две переменные: TARGET — для определения имени целевой программы и PREFIX — для определения пути установки программы в систему.

Это уже посимпатичней. Думаю, теперь вышеприведенный пример для вас в особых комментариях не нуждается.

Автоматические переменные

Автоматические переменные предназначены для упрощения мейкфайлов, но на мой взгляд негативно сказываются на их читабельности. Как бы то ни было, я приведу здесь несколько наиболее часто используемых переменных, а что с ними делать (и делать ли вообще) решать вам:

Getting Started

Why do Makefiles exist?

Makefiles are used to help decide which parts of a large program need to be recompiled. In the vast majority of cases, C or C++ files are compiled. Other languages typically have their own tools that serve a similar purpose as Make. It can be used beyond programs too, when you need a series of instructions to run depending on what files have changed. This tutorial will focus on the C/C++ compilation use case.

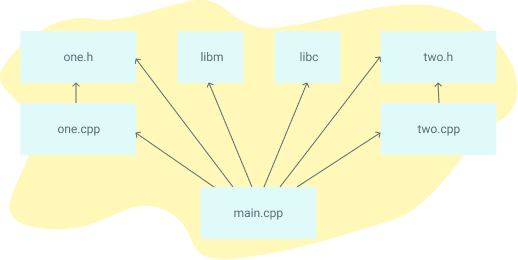

Here’s an example dependency graph that you might build with Make. If any file’s dependencies changes, then the file will get recompiled:

What alternatives are there to Make?

Popular C/C++ alternative build systems are SCons, CMake, Bazel, and Ninja. Some code editors like Microsoft Visual Studio have their own built in build tools. For Java, there’s Ant, Maven, and Gradle. Other languages like Go and Rust have their own build tools.

Interpreted languages like Python, Ruby, and Javascript don’t require an analogue to Makefiles. The goal of Makefiles is to compile whatever files need to be compiled, based on what files have changed. But when files in interpreted languages change, nothing needs to get recompiled. When the program runs, the most recent version of the file is used.

The versions and types of Make

There are a variety of implementations of Make, but most of this guide will work on whatever version you’re using. However, it’s specifically written for GNU Make, which is the standard implementation on Linux and MacOS. All the examples work for Make versions 3 and 4, which are nearly equivalent other than some esoteric differences.

Running the Examples

Note: Makefiles must be indented using TABs and not spaces or make will fail.

Here is the output of running the above example:

That’s it! If you’re a bit confused, here’s a video that goes through these steps, along with describing the basic structure of Makefiles.

Makefile Syntax

A Makefile consists of a set of rules. A rule generally looks like this:

Beginner Examples

The following Makefile has three separate rules. When you run make blah in the terminal, it will build a program called blah in a series of steps:

This file will make some_file the first time, and the second time notice it’s already made, resulting in make: ‘some_file’ is up to date.

This will always run both targets, because some_file depends on other_file, which is never created.

Variables

Here’s an example of using variables:

Targets

The all target

Making multiple targets and you want all of them to run? Make an all target.

Multiple targets

When there are multiple targets for a rule, the commands will be run for each target

$@ is an automatic variable that contains the target name.

Automatic Variables and Wildcards

* Wildcard

Both * and % are called wildcards in Make, but they mean entirely different things. * searches your filesystem for matching filenames. I suggest that you always wrap it in the wildcard function, because otherwise you may fall into a common pitfall described below.

* may be used in the target, prerequisites, or in the wildcard function.

Danger: * may not be directly used in a variable definitions

Danger: When * matches no files, it is left as it is (unless run in the wildcard function)

% Wildcard

% is really useful, but is somewhat confusing because of the variety of situations it can be used in.

See these sections on examples of it being used:

Automatic Variables

There are many automatic variables, but often only a few show up:

Fancy Rules

Implicit Rules

Make loves c compilation. And every time it expresses its love, things get confusing. Perhaps the most confusing part of Make is the magic/automatic rules that are made. Make calls these «implicit» rules. I don’t personally agree with this design decision, and I don’t recommend using them, but they’re often used and are thus useful to know. Here’s a list of implicit rules:

The important variables used by implicit rules are:

Let’s see how we can now build a C program without ever explicitly telling Make how to do the compililation:

Static Pattern Rules

Static pattern rules are another way to write less in a Makefile, but I’d say are more useful and a bit less «magic». Here’s their syntax:

Here’s the more efficient way, using a static pattern rule:

Static Pattern Rules and Filter

Pattern Rules

Pattern rules are often used but quite confusing. You can look at them as two ways:

Let’s start with an example first:

Pattern rules contain a ‘%’ in the target. This ‘%’ matches any nonempty string, and the other characters match themselves. ‘%’ in a prerequisite of a pattern rule stands for the same stem that was matched by the ‘%’ in the target.

Here’s another example:

Double-Colon Rules

Double-Colon Rules are rarely used, but allow multiple rules to be defined for the same target. If these were single colons, a warning would be printed and only the second set of commands would run.

Commands and execution

Command Echoing/Silencing

Command Execution

Each command is run in a new shell (or at least the effect is as such)

Default Shell

Interrupting or killing make

Note only: If you ctrl+c make, it will delete the newer targets it just made.

Recursive use of make

Use export for recursive make

The export directive takes a variable and makes it accessible to sub-make commands. In this example, cooly is exported such that the makefile in subdir can use it.

Note: export has the same syntax as sh, but they aren’t related (although similar in function)

You need to export variables to have them run in the shell as well.

.EXPORT_ALL_VARIABLES exports all variables for you.

Arguments to make

Variables Pt. 2

Flavors and modification

There are two flavors of variables:

Simply expanded (using := ) allows you to append to a variable. Recursive definitions will give an infinite loop error.

?= only sets variables if they have not yet been set

An undefined variable is actually an empty string!

String Substitution is also a really common and useful way to modify variables. Also check out Text Functions and Filename Functions.

Command line arguments and override

List of commands and define

«define» is actually just a list of commands. It has nothing to do with being a function. Note here that it’s a bit different than having a semi-colon between commands, because each is run in a separate shell, as expected.

Target-specific variables

Variables can be assigned for specific targets

Pattern-specific variables

You can assign variables for specific target patterns

Conditional part of Makefiles

Conditional if/else

Check if a variable is empty

Check if a variable is defined

ifdef does not expand variable references; it just sees if something is defined at all

$(makeflags)

Functions

First Functions

If you want to replace spaces or commas, use variables

Do NOT include spaces in the arguments after the first. That will be seen as part of the string.

String Substitution

$(patsubst pattern,replacement,text) does the following:

«Finds whitespace-separated words in text that match pattern and replaces them with replacement. Here pattern may contain a ‘%’ which acts as a wildcard, matching any number of any characters within a word. If replacement also contains a ‘%’, the ‘%’ is replaced by the text that matched the ‘%’ in pattern. Only the first ‘%’ in the pattern and replacement is treated this way; any subsequent ‘%’ is unchanged.» (GNU docs)

Note: don’t add extra spaces for this shorthand. It will be seen as a search or replacement term.

The foreach function

The if function

if checks if the first argument is nonempty. If so runs the second argument, otherwise runs the third.

The call function

The shell function

Other Features

Include Makefiles

The include directive tells make to read one or more other makefiles. It’s a line in the makefile makefile that looks like this:

The vpath Directive

Use vpath to specify where some set of prerequisites exist. The format is vpath

Multiline

The backslash («\») character gives us the ability to use multiple lines when the commands are too long

.phony

.delete_on_error

The make tool will stop running a rule (and will propogate back to prerequisites) if a command returns a nonzero exit status.

DELETE_ON_ERROR will delete the target of a rule if the rule fails in this manner. This will happen for all targets, not just the one it is before like PHONY. It’s a good idea to always use this, even though make does not for historical reasons.

Makefile Cookbook

Let’s go through a really juicy Make example that works well for medium sized projects.

The neat thing about this makefile is it automatically determines dependencies for you. All you have to do is put your C/C++ files in the src/ folder.

How to create makefile

A Simple Makefile Tutorial

Makefiles are a simple way to organize code compilation. This tutorial does not even scratch the surface of what is possible using make, but is intended as a starters guide so that you can quickly and easily create your own makefiles for small to medium-sized projects.

A Simple Example

Let’s start off with the following three files, hellomake.c, hellofunc.c, and hellomake.h, which would represent a typical main program, some functional code in a separate file, and an include file, respectively.

| hellomake.c | hellofunc.c | hellomake.h |

|---|

Normally, you would compile this collection of code by executing the following command:

The simplest makefile you could create would look something like:

If you put this rule into a file called Makefile or makefile and then type make on the command line it will execute the compile command as you have written it in the makefile. Note that make with no arguments executes the first rule in the file. Furthermore, by putting the list of files on which the command depends on the first line after the :, make knows that the rule hellomake needs to be executed if any of those files change. Immediately, you have solved problem #1 and can avoid using the up arrow repeatedly, looking for your last compile command. However, the system is still not being efficient in terms of compiling only the latest changes.

One very important thing to note is that there is a tab before the gcc command in the makefile. There must be a tab at the beginning of any command, and make will not be happy if it’s not there.

In order to be a bit more efficient, let’s try the following:

As a final simplification, let’s use the special macros $@ and $^, which are the left and right sides of the :, respectively, to make the overall compilation rule more general. In the example below, all of the include files should be listed as part of the macro DEPS, and all of the object files should be listed as part of the macro OBJ.

So now you have a perfectly good makefile that you can modify to manage small and medium-sized software projects. You can add multiple rules to a makefile; you can even create rules that call other rules. For more information on makefiles and the make function, check out the GNU Make Manual, which will tell you more than you ever wanted to know (really).