How to get ssh key

How to get ssh key

Welcome to our ultimate guide to setting up SSH (Secure Shell) keys. This tutorial will walk you through the basics of creating SSH keys, and also how to manage multiple keys and key pairs.

Create a New SSH Key Pair

Open a terminal and run the following command:

You will see the following text:

Press enter to save your keys to the default /home/username/.ssh directory.

Then you’ll be prompted to enter a password:

It’s recommended to enter a password here for an extra layer of security. By setting a password, you could prevent unauthorized access to your servers and accounts if someone ever gets a hold of your private SSH key or your machine.

After entering and confirming your password, you’ll see the following:

You now have a public and private SSH key pair you can use to access remote servers and to handle authentication for command line programs like Git.

Manage Multiple SSH Keys

Though it’s considered good practice to have only one public-private key pair per device, sometimes you need to use multiple keys or you have unorthodox key names. For example, you might be using one SSH key pair for working on your company’s internal projects, but you might be using a different key for accessing a client’s servers. On top of that, you might be using a different key pair for accessing your own private server.

A better solution is to automate adding keys, store passwords, and to specify which key to use when accessing certain servers.

SSH config

/.ssh/config and open it for editing:

Managing Custom Named SSH key

Next, make sure that

/.ssh/id_rsa is not in ssh-agent by opening another terminal and running the following command:

This command will remove all keys from currently active ssh-agent session.

Now if you try closing a GitHub repository, your config file will use the key at

Here are some other useful configuration examples:

Now you can use git clone git@bitbucket-corporate:company/project.git

Now you can use git clone git@bitbucket-personal:username/other-pi-project.git

Password management

The last piece of the puzzle is managing passwords. It can get very tedious entering a password every time you initialize an SSH connection. To get around this, we can use the password management software that comes with macOS and various Linux distributions.

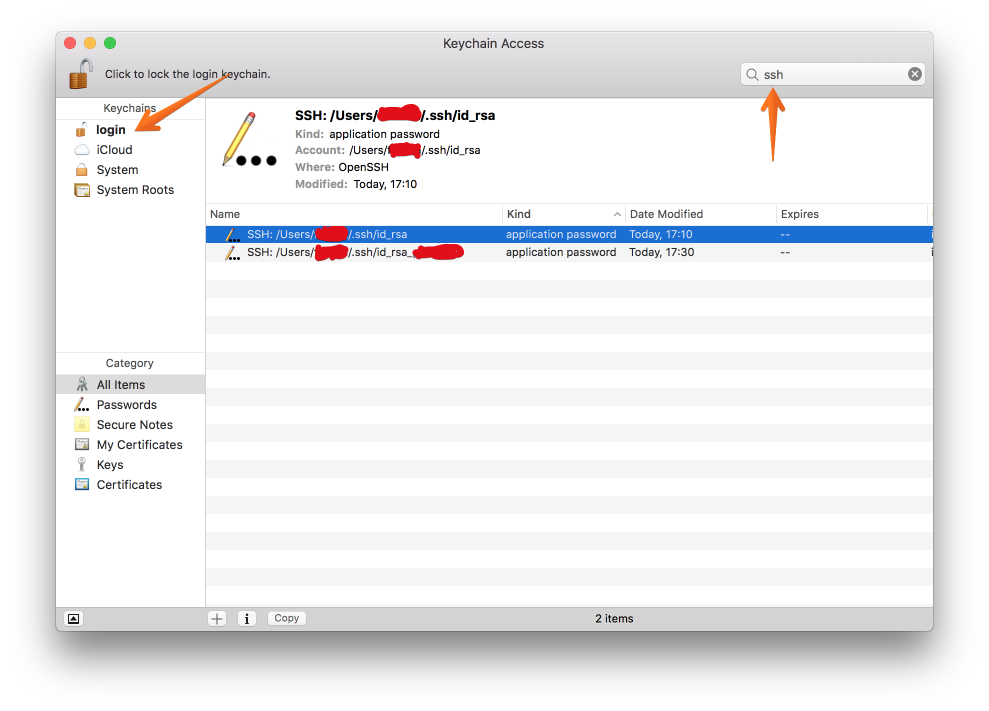

Now you can see your SSH key in Keychain Access:

/.ssh/config and add the following:

With that, whenever you run ssh it will look for keys in Keychain Access. If it finds one, you will no longer be prompted for a password. Keys will also automatically be added to ssh-agent every time you restart your machine.

Now that you know the basics of creating new SSH keys and managing multiple keys, go out and ssh to your heart’s content!

Learn to code for free. freeCodeCamp’s open source curriculum has helped more than 40,000 people get jobs as developers. Get started

freeCodeCamp is a donor-supported tax-exempt 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization (United States Federal Tax Identification Number: 82-0779546)

Donations to freeCodeCamp go toward our education initiatives, and help pay for servers, services, and staff.

SSH keys

SSH keys can serve as a means of identifying yourself to an SSH server using public-key cryptography and challenge-response authentication. The major advantage of key-based authentication is that, in contrast to password authentication, it is not prone to brute-force attacks, and you do not expose valid credentials if the server has been compromised (see RFC 4251 9.4.4).

Furthermore, SSH key authentication can be more convenient than the more traditional password authentication. When used with a program known as an SSH agent, SSH keys can allow you to connect to a server, or multiple servers, without having to remember or enter your password for each system.

Key-based authentication is not without its drawbacks and may not be appropriate for all environments, but in many circumstances it can offer some strong advantages. A general understanding of how SSH keys work will help you decide how and when to use them to meet your needs.

This article assumes you already have a basic understanding of the Secure Shell protocol and have installed the openssh package.

Contents

Background

SSH keys are always generated in pairs with one known as the private key and the other as the public key. The private key is known only to you and it should be safely guarded. By contrast, the public key can be shared freely with any SSH server to which you wish to connect.

If an SSH server has your public key on file and sees you requesting a connection, it uses your public key to construct and send you a challenge. This challenge is an encrypted message and it must be met with the appropriate response before the server will grant you access. What makes this coded message particularly secure is that it can only be understood by the private key holder. While the public key can be used to encrypt the message, it cannot be used to decrypt that very same message. Only you, the holder of the private key, will be able to correctly understand the challenge and produce the proper response.

This challenge-response phase happens behind the scenes and is invisible to the user. As long as you hold the private key, which is typically stored in the

/.ssh/ directory, your SSH client should be able to reply with the appropriate response to the server.

A private key is a guarded secret and as such it is advisable to store it on disk in an encrypted form. When the encrypted private key is required, a passphrase must first be entered in order to decrypt it. While this might superficially appear as though you are providing a login password to the SSH server, the passphrase is only used to decrypt the private key on the local system. The passphrase is not transmitted over the network.

Generating an SSH key pair

An SSH key pair can be generated by running the ssh-keygen command, defaulting to 3072-bit RSA (and SHA256) which the ssh-keygen(1) man page says is «generally considered sufficient» and should be compatible with virtually all clients and servers:

The randomart image was introduced in OpenSSH 5.1 as an easier means of visually identifying the key fingerprint.

will add a comment saying which user created the key on which machine and when.

Choosing the authentication key type

OpenSSH supports several signing algorithms (for authentication keys) which can be divided in two groups depending on the mathematical properties they exploit:

Elliptic curve cryptography (ECC) algorithms are a more recent addition to public key cryptosystems. One of their main advantages is their ability to provide the same level of security with smaller keys, which makes for less computationally intensive operations (i.e. faster key creation, encryption and decryption) and reduced storage and transmission requirements.

OpenSSH 7.0 deprecated and disabled support for DSA keys due to discovered vulnerabilities, therefore the choice of cryptosystem lies within RSA or one of the two types of ECC.

#RSA keys will give you the greatest portability, while #Ed25519 will give you the best security but requires recent versions of client & server[1]. #ECDSA is likely more compatible than Ed25519 (though still less than RSA), but suspicions exist about its security (see below).

Minimum key size is 1024 bits, default is 3072 (see ssh-keygen(1) ) and maximum is 16384.

Be aware though that there are diminishing returns in using longer keys.[2][3] The GnuPG FAQ reads: «If you need more security than RSA-2048 offers, the way to go would be to switch to elliptical curve cryptography — not to continue using RSA.»[4]

On the other hand, the latest iteration of the NSA Fact Sheet Suite B Cryptography suggests a minimum 3072-bit modulus for RSA while «[preparing] for the upcoming quantum resistant algorithm transition«.[5]

ECDSA

The Elliptic Curve Digital Signature Algorithm (ECDSA) was introduced as the preferred algorithm for authentication in OpenSSH 5.7. Some vendors also disable the required implementations due to potential patent issues.

There are two sorts of concerns with it:

Both of those concerns are best summarized in libssh curve25519 introduction. Although the political concerns are still subject to debate, there is a clear consensus that #Ed25519 is technically superior and should therefore be preferred.

Ed25519

Ed25519 was introduced in OpenSSH 6.5 of January 2014: «Ed25519 is an elliptic curve signature scheme that offers better security than ECDSA and DSA and good performance«. Its main strengths are its speed, its constant-time run time (and resistance against side-channel attacks), and its lack of nebulous hard-coded constants.[6] See also this blog post by a Mozilla developer on how it works.

It is already implemented in many applications and libraries and is the default key exchange algorithm (which is different from key signature) in OpenSSH.

Ed25519 key pairs can be generated with:

There is no need to set the key size, as all Ed25519 keys are 256 bits.

Keep in mind that older SSH clients and servers may not support these keys.

FIDO/U2F

FIDO/U2F hardware authenticator support was added in OpenSSH version 8.2 for both of the elliptic curve signature schemes mentioned above. It allows for a hardware token attached via USB or other means to act a second factor alongside the private key.

The libfido2 is required for hardware token support.

After attaching a compatible FIDO key, a key pair may be generated with:

To create keys that do not require touch events, generate a key pair with the no-touch-required option. For example:

Additionally, sshd rejects no-touch-required keys by default. To allow keys generated with this option, either enable it for an individual key in the authorized_keys file,

or for the whole system by editing /etc/ssh/sshd_config with

An ECDSA-based keypair may also be generated with the ecdsa-sk keytype, but the relevant concerns in the #ECDSA section above still apply.

Choosing the key location and passphrase

Upon issuing the ssh-keygen command, you will be prompted for the desired name and location of your private key. By default, keys are stored in the

/.ssh/ directory and named according to the type of encryption used. You are advised to accept the default name and location in order for later code examples in this article to work properly.

When prompted for a passphrase, choose something that will be hard to guess if you have the security of your private key in mind. A longer, more random password will generally be stronger and harder to crack should it fall into the wrong hands.

It is also possible to create your private key without a passphrase. While this can be convenient, you need to be aware of the associated risks. Without a passphrase, your private key will be stored on disk in an unencrypted form. Anyone who gains access to your private key file will then be able to assume your identity on any SSH server to which you connect using key-based authentication. Furthermore, without a passphrase, you must also trust the root user, as they can bypass file permissions and will be able to access your unencrypted private key file at any time.

Changing the private key’s passphrase without changing the key

If the originally chosen SSH key passphrase is undesirable or must be changed, one can use the ssh-keygen command to change the passphrase without changing the actual key. This can also be used to change the password encoding format to the new standard.

Managing multiple keys

If you have multiple SSH identities, you can set different keys to be used for different hosts or remote users by using the Match and IdentityFile directives in your configuration:

See ssh_config(5) for full description of these options.

Storing SSH keys on hardware tokens

SSH keys can also be stored on a security token like a smart card or a USB token. This has the advantage that the private key is stored securely on the token instead of being stored on disk. When using a security token the sensitive private key is also never present in the RAM of the PC; the cryptographic operations are performed on the token itself. A cryptographic token has the additional advantage that it is not bound to a single computer; it can easily be removed from the computer and carried around to be used on other computers.

Examples are hardware tokens are described in:

Copying the public key to the remote server

Simple method

If your key file is

/.ssh/id_rsa.pub you can simply enter the following command.

If your username differs on remote machine, be sure to prepend the username followed by @ to the server name.

If your public key filename is anything other than the default of

If the ssh server is listening on a port other than default of 22, be sure to include it within the host argument.

Manual method

By default, for OpenSSH, the public key needs to be concatenated with

On the remote server, you will need to create the

/.ssh directory if it does not yet exist and append your public key to the authorized_keys file.

The last two commands remove the public key file from the server and set the permissions on the authorized_keys file such that it is only readable and writable by you, the owner.

SSH agents

If your private key is encrypted with a passphrase, this passphrase must be entered every time you attempt to connect to an SSH server using public-key authentication. Each individual invocation of ssh or scp will need the passphrase in order to decrypt your private key before authentication can proceed.

An SSH agent is a program which caches your decrypted private keys and provides them to SSH client programs on your behalf. In this arrangement, you must only provide your passphrase once, when adding your private key to the agent’s cache. This facility can be of great convenience when making frequent SSH connections.

An agent is typically configured to run automatically upon login and persist for the duration of your login session. A variety of agents, front-ends, and configurations exist to achieve this effect. This section provides an overview of a number of different solutions which can be adapted to meet your specific needs.

ssh-agent

ssh-agent is the default agent included with OpenSSH. It can be used directly or serve as the back-end to a few of the front-end solutions mentioned later in this section. When ssh-agent is run, it forks to background and prints necessary environment variables. E.g.

To make use of these variables, run the command through the eval command.

Once ssh-agent is running, you will need to add your private key to its cache:

If your private key is encrypted, ssh-add will prompt you to enter your passphrase. Once your private key has been successfully added to the agent you will be able to make SSH connections without having to enter your passphrase.

In order to start the agent automatically and make sure that only one ssh-agent process runs at a time, add the following to your

This will run a ssh-agent process if there is not one already, and save the output thereof. If there is one running already, we retrieve the cached ssh-agent output and evaluate it which will set the necessary environment variables. The lifetime of the unlocked keys is set to 1 hour.

There also exist a number of front-ends to ssh-agent and alternative agents described later in this section which avoid this problem.

Start ssh-agent with systemd user

It is possible to use the systemd/User facilities to start the agent. Use this if you would like your ssh agent to run when you are logged in, regardless of whether x is running.

Then export the environment variable SSH_AUTH_SOCK=»$XDG_RUNTIME_DIR/ssh-agent.socket» in your login shell initialization file, such as

ssh-agent as a wrapper program

An alternative way to start ssh-agent (with, say, each X session) is described in this ssh-agent tutorial by UC Berkeley Labs. A basic use case is if you normally begin X with the startx command, you can instead prefix it with ssh-agent like so:

Doing it this way avoids the problem of having extraneous ssh-agent instances floating around between login sessions. Exactly one instance will live and die with the entire X session.

See the below notes on using x11-ssh-askpass with ssh-add for an idea on how to immediately add your key to the agent.

GnuPG Agent

The gpg-agent has OpenSSH Agent protocol emulation. See GnuPG#SSH agent for necessary configuration.

Keychain

Keychain is a program designed to help you easily manage your SSH keys with minimal user interaction. It is implemented as a shell script which drives both ssh-agent and ssh-add. A notable feature of Keychain is that it can maintain a single ssh-agent process across multiple login sessions. This means that you only need to enter your passphrase once each time your local machine is booted.

Installation

Configuration

Add a line similar to the following to your shell configuration file, e.g. if using Bash:

/.bashrc is used instead of the upstream suggested

/.bash_profile because on Arch it is sourced by both login and non-login shells, making it suitable for textual and graphical environments alike. See Bash#Invocation for more information on the difference between those.

In the above example,

Multiple keys can be specified on the command line, as shown in the example. By default keychain will look for key pairs in the

/.ssh/config for IdentityFile settings defined for particular hosts, and use these paths to locate keys.

Because Keychain reuses the same ssh-agent process on successive logins, you should not have to enter your passphrase the next time you log in or open a new terminal. You will only be prompted for your passphrase once each time the machine is rebooted.

x11-ssh-askpass

The x11-ssh-askpass package provides a graphical dialog for entering your passhrase when running an X session. x11-ssh-askpass depends only on the libx11 and libxt libraries, and the appearance of x11-ssh-askpass is customizable. While it can be invoked by the ssh-add program, which will then load your decrypted keys into ssh-agent, the following instructions will, instead, configure x11-ssh-askpass to be invoked by the aforementioned Keychain script.

Install the keychain and x11-ssh-askpass packages.

/.xinitrc file to include the following lines, replacing the name and location of your private key if necessary. Be sure to place these commands before the line which invokes your window manager.

Calling x11-ssh-askpass with ssh-add

This is assuming that

and your X resources will contain something like:

Doing it this way works well with the above method on using ssh-agent as a wrapper program. You start X with ssh-agent startx and then add ssh-add to your window manager’s list of start-up programs.

Theming

Alternative passphrase dialogs

There are other passphrase dialog programs which can be used instead of x11-ssh-askpass. The following list provides some alternative solutions.

pam_ssh

The pam_ssh project exists to provide a Pluggable Authentication Module (PAM) for SSH private keys. This module can provide single sign-on behavior for your SSH connections. On login, your SSH private key passphrase can be entered in place of, or in addition to, your traditional system password. Once you have been authenticated, the pam_ssh module spawns ssh-agent to store your decrypted private key for the duration of the session.

To enable single sign-on behavior at the tty login prompt, install the unofficial pam_ssh AUR package.

Create a symlink to your private key file and place it in

Edit the /etc/pam.d/login configuration file to include the text highlighted in bold in the example below. The order in which these lines appear is significiant and can affect login behavior.

In the above example, login authentication initially proceeds as it normally would, with the user being prompted to enter their user password. The additional auth authentication rule added to the end of the authentication stack then instructs the pam_ssh module to try to decrypt any private keys found in the

/.ssh/login-keys.d directory. The try_first_pass option is passed to the pam_ssh module, instructing it to first try to decrypt any SSH private keys using the previously entered user password. If the user’s private key passphrase and user password are the same, this should succeed and the user will not be prompted to enter the same password twice. In the case where the user’s private key passphrase user password differ, the pam_ssh module will prompt the user to enter the SSH passphrase after the user password has been entered. The optional control value ensures that users without an SSH private key are still able to log in. In this way, the use of pam_ssh will be transparent to users without an SSH private key.

If you use another means of logging in, such as an X11 display manager like SLiM or XDM and you would like it to provide similar functionality, you must edit its associated PAM configuration file in a similar fashion. Packages providing support for PAM typically place a default configuration file in the /etc/pam.d/ directory.

Further details on how to use pam_ssh and a list of its options can be found in the pam_ssh(8) man page.

Using a different password to unlock the SSH key

If you want to unlock the SSH keys or not depending on whether you use your key’s passphrase or the (different!) login password, you can modify /etc/pam.d/system-auth to

For an explanation, see [8].

Known issues with pam_ssh

Work on the pam_ssh project is infrequent and the documentation provided is sparse. You should be aware of some of its limitations which are not mentioned in the package itself.

pam_exec-ssh

GNOME Keyring

If you use the GNOME desktop, the GNOME Keyring tool can be used as an SSH agent. See the GNOME Keyring article for further details.

Store SSH keys with Kwallet

For instructions on how to use kwallet to store your SSH keys, see KDE Wallet#Using the KDE Wallet to store ssh key passphrases.

KeePass2 with KeeAgent plugin

KeeAgent is a plugin for KeePass that allows SSH keys stored in a KeePass database to be used for SSH authentication by other programs.

KeePassXC

The KeePassXC fork of KeePass can act as a client for an existing SSH agent. SSH keys stored in its database can be automatically (or manually) added to the agent. It is also compatible with KeeAgent’s database format.

Troubleshooting

Key ignored by the server

How do I access my SSH public key?

I’ve just generated my RSA key pair, and I wanted to add that key to GitHub.

23 Answers 23

Trending sort

Trending sort is based off of the default sorting method — by highest score — but it boosts votes that have happened recently, helping to surface more up-to-date answers.

It falls back to sorting by highest score if no posts are trending.

Switch to Trending sort

/.ssh/id_rsa.pub or cat

You can list all the public keys you have by doing:

Copy the key to your clipboard.

Warning: it’s important to copy the key exactly without adding newlines or whitespace. Thankfully the pbcopy command makes it easy to perform this setup perfectly.

and paste it wherever you need.

You may try to run the following command to show your RSA fingerprint:

If you’ve the message: ‘The agent has no identities.’, then you’ve to generate your RSA key by ssh-keygen first.

/.ssh folder. I much prefer to use my PGP key for authentication and so I do not have a

/.ssh/id_rsa.pub file at all.

If you’re on Windows use the following, select all, and copy from a Notepad window:

If you’re on OS X, use:

Mac, Ubuntu, Linux compatible machines, use this command to print public key, then copy it:

Here’s how I found mine on OS X:

On terminal cat

explanation

After you generate your SSH key you can do:

which will copy your ssh key into your clipboard.

If you’re using windows, the command is:

it should print the key (if you have one). You should copy the entire result. If none is present, then do:

If you are using Windows PowerShell, the easiest way is to:

That will copy the key to your clipboard for easy pasting.

So, in my instance, I use ed25519 since RSA is now fairly hackable:

Because I find myself doing this a lot, I created a function and set a simple alias I could remember in my PowerShell profile (learn more about PowerShell profiles here. Just add this to your Microsoft.PowerShell_profile.ps1 :

Памятка пользователям ssh

Предупреждение: пост очень объёмный, но для удобства использования я решил не резать его на части.

Управление ключами

Теория в нескольких словах: ssh может авторизоваться не по паролю, а по ключу. Ключ состоит из открытой и закрытой части. Открытая кладётся в домашний каталог пользователя, «которым» заходят на сервер, закрытая — в домашний каталог пользователя, который идёт на удалённый сервер. Половинки сравниваются (я утрирую) и если всё ок — пускают. Важно: авторизуется не только клиент на сервере, но и сервер по отношению к клиенту (то есть у сервера есть свой собственный ключ). Главной особенностью ключа по сравнению с паролем является то, что его нельзя «украсть», взломав сервер — ключ не передаётся с клиента на сервер, а во время авторизации клиент доказывает серверу, что владеет ключом (та самая криптографическая магия).

Генерация ключа

Свой ключ можно сгенерировать с помощью команды ssh-keygen. Если не задать параметры, то он сохранит всё так, как надо.

Ключ можно закрыть паролем. Этот пароль (в обычных графических интерфейсах) спрашивается один раз и сохраняется некоторое время. Если пароль указать пустым, он спрашиваться при использовании не будет. Восстановить забытый пароль невозможно.

Структура ключа

/.ssh/id_rsa.pub — открытый ключ. Его копируют на сервера, куда нужно получить доступ.

/.ssh/id_rsa — закрытый ключ. Его нельзя никому показывать. Если вы в письмо/чат скопипастите его вместо pub, то нужно генерировать новый ключ. (Я не шучу, примерно 10% людей, которых просишь дать ssh-ключ постят id_rsa, причём из этих десяти процентов мужского пола 100%).

Копирование ключа на сервер

/.ssh/authorized_keys и положить туда открытый ключ, то можно будет заходить без пароля. Обратите внимание, права на файл не должны давать возможность писать в этот файл посторонним пользователям, иначе ssh его не примет. В ключе последнее поле — user@machine. Оно не имеет никакого отношения к авторизации и служит только для удобства определения где чей ключ. Заметим, это поле может быть поменяно (или даже удалено) без нарушения структуры ключа.

Если вы знаете пароль пользователя, то процесс можно упростить. Команда ssh-copy-id user@server позволяет скопировать ключ не редактируя файлы вручную.

Замечание: Старые руководства по ssh упоминают про authorized_keys2. Причина: была первая версия ssh, потом стала вторая (текущая), для неё сделали свой набор конфигов, всех это очень утомило, и вторая версия уже давным давно переключилась на версии без всяких «2». То есть всегда authorized_keys и не думать о разных версиях.

Если у вас ssh на нестандартном порту, то ssh-copy-id требует особого ухищрения при работе: ssh-copy-id ‘-p 443 user@server’ (внимание на кавычки).

Ключ сервера

/.ssh/known_hosts. Узнать, где какой ключ нельзя (ибо несекьюрно).

Если ключ сервера поменялся (например, сервер переустановили), ssh вопит от подделке ключа. Обратите внимание, если сервер не трогали, а ssh вопит, значит вы не на тот сервер ломитесь (например, в сети появился ещё один компьютер с тем же IP, особо этим страдают всякие локальные сети с 192.168.1.1, которых в мире несколько миллионов). Сценарий «злобной man in the middle атаки» маловероятен, чаще просто ошибка с IP, хотя если «всё хорошо», а ключ поменялся — это повод поднять уровень паранойи на пару уровней (а если у вас авторизация по ключу, а сервер вдруг запросил пароль — то паранойю можно включать на 100% и пароль не вводить).

Ключ сервера хранится в /etc/ssh/ssh_host_rsa_key и /etc/ssh/ssh_host_rsa_key.pub. Их можно:

а) скопировать со старого сервера на новый.

б) сгенерировать с помощью ssh-keygen. Пароля при этом задавать не надо (т.е. пустой). Ключ с паролем ssh-сервер использовать не сможет.

Заметим, если вы сервера клонируете (например, в виртуалках), то ssh-ключи сервера нужно обязательно перегенерировать.

Старые ключи из know_hosts при этом лучше убрать, иначе ssh будет ругаться на duplicate key.

Копирование файлов

Передача файлов на сервер иногда может утомлять. Помимо возни с sftp и прочими странными вещами, ssh предоставляет нам команду scp, которая осуществляет копирование файла через ssh-сессию.

scp path/myfile user@8.8.8.8:/full/path/to/new/location/

Обратно тоже можно:

scp user@8.8.8.8:/full/path/to/file /path/to/put/here

Fish warning: Не смотря на то, что mc умеет делать соединение по ssh, копировать большие файлы будет очень мучительно, т.к. fish (модуль mc для работы с ssh как с виртуальной fs) работает очень медленно. 100-200кб — предел, дальше начинается испытание терпения. (Я вспомнил свою очень раннюю молодость, когда не зная про scp, я копировал

5Гб через fish в mc, заняло это чуть больше 12 часов на FastEthernet).

Возможность копировать здорово. Но хочется так, чтобы «сохранить как» — и сразу на сервер. И чтобы в графическом режиме копировать не из специальной программы, а из любой, привычной.

sshfs

Теория: модуль fuse позволяет «экспортировать» запросы к файловой системе из ядра обратно в userspace к соответствующей программе. Это позволяет легко реализовывать «псевдофайловые системы». Например, мы можем предоставить доступ к удалённой файловой системе через ssh так, что все локальные приложения (за малым исключением) не будут ничего подозревать.

Собственно, исключение: O_DIRECT не поддерживается, увы (это проблема не sshfs, это проблема fuse вообще).

Использование: установить пакет sshfs (сам притащит за собой fuse).

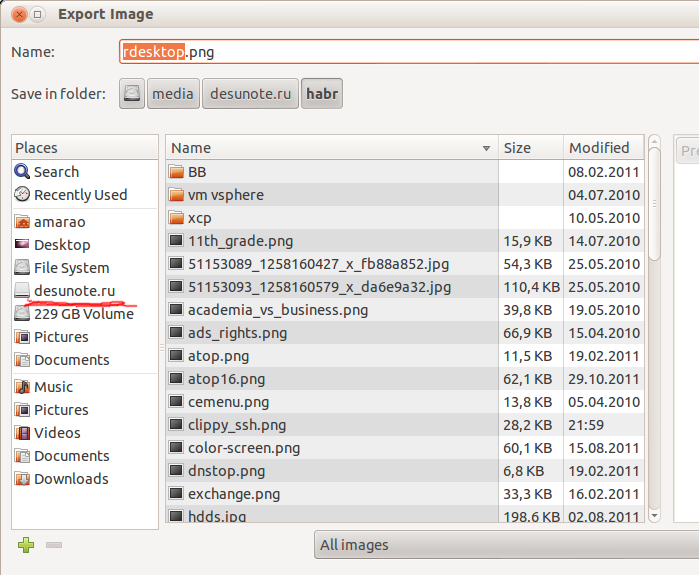

Собственно, пример моего скрипта, который монтирует desunote.ru (размещающийся у меня на домашнем комьютере — с него в этой статье показываются картинки) на мой ноут:

Делаем файл +x, вызываем, идём в любое приложение, говорим сохранить и видим:

Если вы много работаете с данными от рута, то можно (нужно) сделать idmap:

-o idmap=user. Работает она следующим образом: если мы коннектимся как пользователь pupkin@server, а локально работаем как пользователь vasiliy, то мы говорим «считать, что файлы pupkin, это файлы vasiliy». ну или «root», если мы коннектимся как root.

В моём случае idmap не нужен, так как имена пользователей (локальное и удалённое) совпадают.

Заметим, комфортно работать получается только если у нас есть ssh-ключик (см. начало статьи), если нет — авторизация по паролю выбешивает на 2-3 подключение.

Удалённое исполнение кода

ssh может выполнить команду на удалённом сервере и тут же закрыть соединение. Простейший пример:

ssh user@server ls /etc/

Выведет нам содержимое /etc/ на server, при этом у нас будет локальная командная строка.

Это нас приводит следующей фиче:

Проброс stdin/out

Допустим, мы хотим сделать запрос к программе удалённо, а потом её вывод поместить в локальный файл

ssh user@8.8.8.8 command >my_file

Допустим, мы хотим локальный вывод положить удалённо

mycommand |scp — user@8.8.8.8:/path/remote_file

Усложним пример — мы можем прокидывать файлы с сервера на сервер: Делаем цепочку, чтобы положить stdin на 10.1.1.2, который нам не доступен снаружи:

mycommand | ssh user@8.8.8.8 «scp — user@10.1.1.2:/path/to/file»

Есть и вот такой головоломный приём использования pipe’а (любезно подсказали в комментариях в жж):

Tar запаковывает файлы по маске локально, пишет их в stdout, откуда их читает ssh, передаёт в stdin на удалённом сервере, где их cd игнорирует (не читает stdin), а tar — читает и распаковывает. Так сказать, scp для бедных.

Алиасы

Скажу честно, до последнего времени не знал и не использовал. Оказались очень удобными.

Можно прописать общесистемные alias’ы на IP (/etc/hosts), но это кривоватый выход (и пользователя и опции всё равно печатать). Есть путь короче.

/.ssh/config позволяет задать параметры подключения, в том числе специальные для серверов, что самое важное, для каждого сервера своё. Вот пример конфига:

Все доступные для использования опции можно увидеть в man ssh_config (не путать с sshd_config).

Опции по умолчанию

По подсказке UUSER: вы можете указать настройки соединения по умолчанию с помощью конструкции Host *, т.е., например:

То же самое можно сделать и в /etc/ssh/ssh_config (не путать с /etc/ssh/sshd_config), но это требует прав рута и распространяется на всех пользователей.

Проброс X-сервера

Собственно, немножко я проспойлерил эту часть в примере конфига выше. ForwardX11 — это как раз оно.

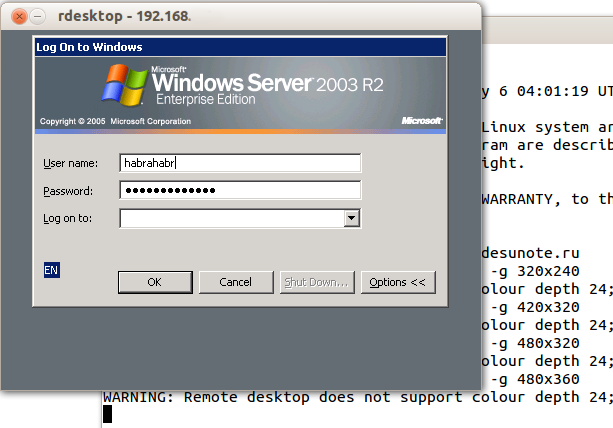

и чудо, окошко логина в windows на нашем рабочем столе. Заметим, тщательно зашифрованное и неотличимое от обычного ssh-трафика.

Socks-proxy

Когда я оказываюсь в очередной гостинице (кафе, конференции), то местный wifi чаще всего оказывается ужасным — закрытые порты, неизвестно какой уровень безопасности. Да и доверия к чужим точкам доступа не особо много (это не паранойя, я вполне наблюдал как уводят пароли и куки с помощью банального ноутбука, раздающего 3G всем желающим с названием близлежащей кафешки (и пишущего интересное в процессе)).

Особые проблемы доставляют закрытые порты. То джаббер прикроют, то IMAP, то ещё что-нибудь.

Обычный VPN (pptp, l2tp, openvpn) в таких ситуациях не работает — его просто не пропускают. Экспериментально известно, что 443ий порт чаще всего оставляют, причём в режиме CONNECT, то есть пропускают «как есть» (обычный http могут ещё прозрачно на сквид завернуть).

Решением служит socks-proxy режим работы ssh. Его принцип: ssh-клиент подключается к серверу и слушает локально. Получив запрос, он отправляет его (через открытое соединение) на сервер, сервер устанавливает соединение согласно запросу и все данные передаёт обратно ssh-клиенту. А тот отвечает обратившемуся. Для работы нужно сказать приложениям «использовать socks-proxy». И указать IP-адрес прокси. В случае с ssh это чаще всего localhost (так вы не отдадите свой канал чужим людям).

Подключение в режиме sock-proxy выглядит так:

Вот так выглядит мой конфиг:

/etc/ssh/sshd_config:

(фрагмент)

Port 22

Port 443

/.ssh/config с ноутбука, который описывает vpn

(обратите внимание на «ленивую» форму записи localhost — 127.1, это вполне себе законный метод написать 127.0.0.1)

Проброс портов

Мы переходим к крайне сложной для понимания части функционала SSH, позволяющей осуществлять головоломные операции по туннелированию TCP «из сервера» и «на сервер».

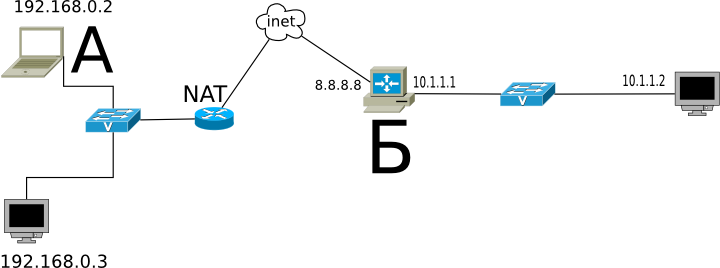

Для понимания ситуации все примеры ниже будут ссылаться на вот эту схему:

Комментарии: Две серые сети. Первая сеть напоминает типичную офисную сеть (NAT), вторая — «гейтвей», то есть сервер с белым интерфейсом и серым, смотрящим в свою собственную приватную сеть. В дальнейших рассуждениях мы полагаем, что «наш» ноутбук — А, а «сервер» — Б.

Задача: у нас локально запущено приложение, нам нужно дать возможность другому пользователю (за пределами нашей сети) посмотреть на него.

Решение: проброс локального порта (127.0.0.1:80) на публично доступный адрес. Допустим, наш «публично доступный» Б занял 80ый порт чем-то полезным, так что пробрасывать мы будем на нестандартный порт (8080).

Итоговая конфигурация: запросы на 8.8.8.8:8080 будут попадать на localhost ноутбука А.

Опция -R позволяет перенаправлять с удалённого (Remote) сервера порт на свой (локальный).

Важно: если мы хотим использовать адрес 8.8.8.8, то нам нужно разрешить GatewayPorts в настройках сервера Б.

Задача. На сервере «Б» слушает некий демон (допустим, sql-сервер). Наше приложение не совместимо с сервером (другая битность, ОС, злой админ, запрещающий и накладывающий лимиты и т.д.). Мы хотим локально получить доступ к удалённому localhost’у.

Итоговая конфигурация: запросы на localhost:3333 на ‘A’ должны обслуживаться демоном на localhost:3128 ‘Б’.

Опция -L позволяет локальные обращения (Local) направлять на удалённый сервер.

Задача: На сервере «Б» на сером интерфейсе слушает некий сервис и мы хотим дать возможность коллеге (192.168.0.3) посмотреть на это приложение.

Итоговая конфигурация: запросы на наш серый IP-адрес (192.168.0.2) попадают на серый интерфейс сервера Б.

Вложенные туннели

Разумеется, туннели можно перенаправлять.

Усложним задачу: теперь нам хочется показать коллеге приложение, запущенное на localhost на сервере с адресом 10.1.1.2 (на 80ом порту).

Что происходит? Мы говорим ssh перенаправлять локальные запросы с нашего адреса на localhost сервера Б и сразу после подключения запустить ssh (то есть клиента ssh) на сервере Б с опцией слушать на localhost и передавать запросы на сервер 10.1.1.2 (куда клиент и должен подключиться). Порт 9999 выбран произвольно, главное, чтобы совпадал в первом вызове и во втором.

Реверс-сокс-прокси

Туннелирование

Если к этому моменту попа отдела безопасности не сияет лысиной, а ssh всё ещё не внесён в список врагов безопасности номер один, вот вам окончательный убийца всего и вся: туннелирование IP или даже ethernet. В самых радикальных случаях это позволяет туннелировать dhcp, заниматься удалённым arp-спуфингом, делать wake up on lan и прочие безобразия второго уровня.

(сам я увы, таким не пользовался).

Легко понять, что в таких условиях невозможно никаким DPI (deep packet inspection) отловить подобные туннели — либо ssh разрешён (читай — делай что хочешь), либо ssh запрещён (и можно смело из такой компании идиотов увольняться не ощущая ни малейшего сожаления).

Проброс авторизации

Если вы думаете, что на этом всё, то…… впрочем, в отличие от автора, у которого «снизу» ещё не написано, читатель заранее видит, что там снизу много букв и интриги не получается.

OpenSSH позволяет использовать сервера в качестве плацдарма для подключения к другим серверам, даже если эти сервера недоверенные и могут злоупотреблять чем хотят.

Для начала о простом пробросе авторизации.

Допустим, мы хотим подключиться к серверу 10.1.1.2, который готов принять наш ключ. Но копировать его на 8.8.8.8 мы не хотим, ибо там проходной двор и половина людей имеет sudo и может шариться по чужим каталогам. Компромиссным вариантом было бы иметь «другой» ssh-ключ, который бы авторизовывал user@8.8.8.8 на 10.1.1.2, но если мы не хотим пускать кого попало с 8.8.8.8 на 10.1.1.2, то это не вариант (тем паче, что ключ могут не только поюзать, но и скопировать себе «на чёрный день»).

Вызов выглядит так:

Удалённый ssh-клиент (на 8.8.8.8) может доказать 10.1.1.2, что мы это мы только если мы к этому серверу подключены и дали ssh-клиенту доступ к своему агенту авторизации (но не ключу!).

В большинстве случаев это прокатывает.

Однако, если сервер совсем дурной, то root сервера может использовать сокет для имперсонализации, когда мы подключены.

Есть ещё более могучий метод — он превращает ssh в простой pipe (в смысле, «трубу») через которую насквозь мы осуществляем работу с удалённым сервером.

Главным достоинством этого метода является полная независимость от доверенности промежуточного сервера. Он может использовать поддельный ssh-сервер, логгировать все байты и все действия, перехватывать любые данные и подделывать их как хочет — взаимодействие идёт между «итоговым» сервером и клиентом. Если данные оконечного сервера подделаны, то подпись не сойдётся. Если данные не подделаны, то сессия устанавливается в защищённом режиме, так что перехватывать нечего.

Эту клёвую настройку я не знал, и раскопал её redrampage.

Выглядит это так (циферки для картинки выше):

Повторю важную мысль: сервер 8.8.8.8 не может перехватить или подделать трафик, воспользоваться агентом авторизации пользователя или иным образом изменить трафик. Запретить — да, может. Но если разрешил — пропустит через себя без расшифровки или модификации. Для работы конфигурации нужно иметь свой открытый ключ в authorized_keys как для user@8.8.8.8, так и в user2@10.1.1.2

Разумеется, подключение можно оснащать всеми прочими фенечками — прокидыванием портов, копированием файлов, сокс-прокси, L2-туннелями, туннелированием X-сервера и т.д.

Ubuntu Documentation

Public and Private Keys

Key-Based SSH Logins

Key-based authentication is the most secure of several modes of authentication usable with OpenSSH, such as plain password and Kerberos tickets. Key-based authentication has several advantages over password authentication, for example the key values are significantly more difficult to brute-force, or guess than plain passwords, provided an ample key length. Other authentication methods are only used in very specific situations.

SSH can use either «RSA» (Rivest-Shamir-Adleman) or «DSA» («Digital Signature Algorithm») keys. Both of these were considered state-of-the-art algorithms when SSH was invented, but DSA has come to be seen as less secure in recent years. RSA is the only recommended choice for new keys, so this guide uses «RSA key» and «SSH key» interchangeably.

Key-based authentication uses two keys, one «public» key that anyone is allowed to see, and another «private» key that only the owner is allowed to see. To securely communicate using key-based authentication, one needs to create a key pair, securely store the private key on the computer one wants to log in from, and store the public key on the computer one wants to log in to.

Using key based logins with ssh is generally considered more secure than using plain password logins. This section of the guide will explain the process of generating a set of public/private RSA keys, and using them for logging into your Ubuntu computer(s) via OpenSSH.

Generating RSA Keys

The first step involves creating a set of RSA keys for use in authentication.

This should be done on the client.

To create your public and private SSH keys on the command-line:

You will be prompted for a location to save the keys, and a passphrase for the keys. This passphrase will protect your private key while it’s stored on the hard drive:

Congratulations! You now have a set of keys. Now it’s time to make your systems allow you to login with them

Choosing a good passphrase

You need to change all your locks if your RSA key is stolen. Otherwise the thief could impersonate you wherever you authenticate with that key.

Your SSH key passphrase is only used to protect your private key from thieves. It’s never transmitted over the Internet, and the strength of your key has nothing to do with the strength of your passphrase.

The decision to protect your key with a passphrase involves convenience x security. Note that if you protect your key with a passphrase, then when you type the passphrase to unlock it, your local computer will generally leave the key unlocked for a time. So if you use the key multiple times without logging out of your local account in the meantime, you will probably only have to type the passphrase once.

If you do adopt a passphrase, pick a strong one and store it securely in a password manager. You may also write it down on a piece of paper and keep it in a secure place. If you choose not to protect the key with a passphrase, then just press the return when ssh-keygen asks.

Key Encryption Level

Password Authentication

The main problem with public key authentication is that you need a secure way of getting the public key onto a computer before you can log in with it. If you will only ever use an SSH key to log in to your own computer from a few other computers (such as logging in to your PC from your laptop), you should copy your SSH keys over on a memory stick, and disable password authentication altogether. If you would like to log in from other computers from time to time (such as a friend’s PC), make sure you have a strong password.

Transfer Client Key to Host

The key you need to transfer to the host is the public one. If you can log in to a computer over SSH using a password, you can transfer your RSA key by doing the following from your own computer:

Where and should be replaced by your username and the name of the computer you’re transferring your key to.

«. If you are using the standard port 22, you can ignore this tip.

Another alternative is to copy the public key file to the server and concatenate it onto the authorized_keys file manually. It is wise to back that up first:

You can make sure this worked by doing:

You should be prompted for the passphrase for your key:

Enter passphrase for key ‘/home/ /.ssh/id_rsa’:

Enter your passphrase, and provided host is configured to allow key-based logins, you should then be logged in as usual.

Troubleshooting

Encrypted Home Directory

If you have an encrypted home directory, SSH cannot access your authorized_keys file because it is inside your encrypted home directory and won’t be available until after you are authenticated. Therefore, SSH will default to password authentication.

To solve this, create a folder outside your home named /etc/ssh/ (replace » » with your actual username). This directory should have 755 permissions and be owned by the user. Move the authorized_keys file into it. The authorized_keys file should have 644 permissions and be owned by the user.

Then edit your /etc/ssh/sshd_config and add:

Finally, restart ssh with:

The next time you connect with SSH you should not have to enter your password.

username@host’s password:

If you are not prompted for the passphrase, and instead get just the

username@host’s password:

prompt as usual with password logins, then read on. There are a few things which could prevent this from working as easily as demonstrated above. On default Ubuntu installs however, the above examples should work. If not, then check the following condition, as it is the most frequent cause:

On the host computer, ensure that the /etc/ssh/sshd_config contains the following lines, and that they are uncommented;

If not, add them, or uncomment them, restart OpenSSH, and try logging in again. If you get the passphrase prompt now, then congratulations, you’re logging in with a key!

Permission denied (publickey)

Permission denied (publickey).

Chances are, your /home/ or

/.ssh/authorized_keys permissions are too open by OpenSSH standards. You can get rid of this problem by issuing the following commands:

Error: Agent admitted failure to sign using the key.

This error occurs when the ssh-agent on the client is not yet managing the key. Issue the following commands to fix:

This command should be entered after you have copied your public key to the host computer.

Debugging and sorting out further problems

The permissions of files and folders is crucial to this working. You can get debugging information from both the client and server.

To connect and send information to the client terminal

Where to From Here?

When the user with the specified key logged in, the server would automatically run /usr/bin/cvs server, ignoring any requests from the client to run another command such as a shell. For more information, see the sshd man page. /755

SSH/OpenSSH/Keys (последним исправлял пользователь larsnooden 2015-07-30 19:26:16)

The material on this wiki is available under a free license, see Copyright / License for details

You can contribute to this wiki, see Wiki Guide for details