How to render the fundamentals of light shadow and reflectivity

How to render the fundamentals of light shadow and reflectivity

Пошаговое рисование девушек от Йоханнса Хелгесона

Иногда Йоханнса спрашивают, о том, как он рисует из головы, и время от времени он показывает демо своим друзьям. Теперь он постарается разъяснить свой процесс и для остальных. Берегитесь, текст и картинки впереди!

Данные действия направлены на то, чтобы получить быстрый и предсказуемый результат. Особенно полезны они будут начинающим художникам, тем кто уже знает Photoshop, но могут оказаться интересными и для более опытных. Это означает рисовать, используя только собственное воображение, Йоханнс достиг этого благодаря годам экспериментов и получая советы от более опытных товарищей (…..). Если перед глазами имеется референс или модель, то его подход будет несколько отличаться, в таком случае Йоханнс сосредоточится на получении более правильной формы, цвета и тона каждого мазка от начала и до конца работы. Photoshop используется здесь как инструмент, чтобы прояснить цвета и тона. Йоханнс любит обращать внимание на то, что его процесс рисования постоянно изменяется, так как он узнаёт новые приёмы, и то как он делает это сейчас, может уже устареть в недалёком будущем. Пожалуйста, относитесь к этому способу критически, и знайте что Йоханнс, пока ещё не достиг уровня мастера в рисовании, он ещё продолжает учиться. Если вы серьёзно настроены чему-либо научиться, то изучайте работы таких мастеров как Zorn, Sargent, J.C. Leyendecker, Rockwell, Velázquez и Sorolla.

Для большей ясности, Йоханнс выложил свой PSD-файл (наполовину уменьшенный в размере), для того, чтобы вы могли прояснить некоторые моменты, которые он не смог облечь в письменную форму.

1.Лайнарт

Здесь просто нарисовано несколько девушек, каждая из которых занята каким-то делом. Если говорить именно о рисунке, то он относится к другой главе, но этот урок будет про покраску. Немного вкратце, здесь он старается получить чистый лайнарт, чтобы использовать его в дальнейшем как основу для рисунка. Чтобы побольше узнать о рисовании, посмотрите канал Stan Prokopenko’s Youtube, также загляните на RadHowto, и обязательно прочитайте Glenn Vilppu’s Drawing Manual и Walt Stanchfield’s Drawn to Life Vol 1 & 2.

2. Маски и Тени-Формы.

В данном случае, лайнарт был замаскирован при помощи «polygonal lasso tool» (нажмите command-key (mac) или ctrl(на PC), чтобы активировать нормальный lasso-tool). Данный инструмент позволяет быстро создавать резкие и твёрдые края. Это наиболее быстрый и аккуратный способ, для маскировки лайнарта, который знает Йоханнс. Например, для маркетинг-арта клиенты часто хотят, чтобы персонажи были отделены от фона, чтобы можно было использовать разное окружение, так что мы заранее сделаем это. Ну а Йоханнс делает это уже по привычке.

3.Выстраивая формы теней

Существует разница между Формообразующими Тенями и Падающими Тенями.

4. Ambient Occlusion

Используя lasso-tool (ни единого мазка без выделения, иначе все края получатся слишком мягкими) и большую мягкую кисть, он затемняет области, которые получают мало света или вообще не освещены. Такой способ хорошо подходит для отделения друг от друга форм одного тона и оттенка. Йоханнс не заморачивается с детализацией на этом этапе. Для этого он использует тёмно-красный цвет. Причиной этому является то, что таким образом ему удаётся симулировать Подповерхностное Рассеивание [3] (подробнее об этом чуть позже) и ещё потому, что глаза человека лучше воспринимают тёплые оттенки (с более короткой длиной волны) и легче их опознают. Ещё одной причиной по которой он это делает, является то, что девушки находятся в большой сцене, с преимущественно холодными цветами (так он её себе представляет), и это создаёт необходимый контраст. Области которые не получают синего холодного света, для наших глаз будут казаться теплее. Таким образом, красный цвет, это обман, то что наши глаза обычно делают в настоящей жизни. [4]

5. Локальные Цвета, Температура и Цветовое Разнообразие

Первым делом, Йоханнс заполняет всё подходящим цветом кожи. Затем, он использует кисть color-randomizer, и парочку текстурных, чтобы добавить разнообразия и усилить участки цвета. Далее, он начинает добавлять температурного разнообразия, вроде красноватых коленей, локтей и щёк, более холодных грудей и бёдер. В основном, Йоханнс думает о том, где кровь находится ближе всего к коже и где это наиболее заметно. Кроме естественного загара, от пребывания на солнце, те девушки, что носят бикини на пляже, получают особый цвет лица и различные по температуре оттенки на отдельных участках тела. Ошибка, которую Йоханнс совершал в прошлом, состояла в том, что он делал этот слой абсолютно плоским, и ТОЛЬКО с одними лишь локальными цветами. Это выглядело тускло и хреново.

6. Окружающий Свет (Ambient Light )

Йоханнс, представляет себе этих девушек находящимися на улице в ясный солнечный день. Тем не менее, огромный синий купол неба, что окружает нас, слегка окрашивает все предметы находящиеся в тенях в холодный синий цвет. Йоханнс добавляет нежный, холодный синий/фиолетовый цвет для повёрнутых к верху плоскостей в тенях (на слое с режимом наложения Screen). Насколько мне известно, слой с режимом наложения Screen, работает как обычный свет в реальной жизни, то есть аддитивно. Очень важно здесь не переборщить, и не сделать слишком яркого по тональности синего света, иначе вы потеряете контраст между тем, что находится в тени и тем, что находится на свету. Йоханнс хочет видеть их в виде двух ясно различимых групп (смотри картинку ниже, шаг 7, где он комбинирует этот шаг и следующий.)

7. Отражённый Свет

8. Ключевой Свет

Просто выбрав слой с формами теней снизу, Йоханнс создаёт новый слой с тенями как маску. Теперь рисуя на освещённых областях, он пользуется большой мягкой кистью с тёплым оттенком. Таким образом, он передает главное направление света, несколькими простыми, большими мазками.

9. SSS – Подповерхностное Рассеивание (Sub Surface Scattering)

На новом слое с режимом наложения Overlay, Йоханнс рисует очень насыщенным красным цветом. Он старается сфокусироваться на рисовании собственной тени/терминатора, и таких мест как пальцы и уши. Подповерхностное рассеивание возникает тогда, когда свет проходит через кожу, получает красный оттенок от крови и отражается обратно, становясь более красным. Это добавляет больше живости цвету, только запомните, что не все материалы работают схожим образом, и кожа особенно восприимчива к подповерхностному рассеиванию.

Теперь Йоханнс объединяет все слои, и чуть меняет цвета корректирующими слоями (adjustment-layers) на свой вкус. Так же, чисто интуитивно, он оставляет немного изначального лайнарта в некоторых местах.

10. Рисуй! Великое Непредсказуемое Путешествие в Шангри-Ла

Всё вышесказанное, было приготовлением перед началом великого путешествия к рисованию. Прочитав всё до этого момента, упакуйте свои вещи, изучите карты и немного ознакомьтесь с языком далёких, экзотических земель. Теперь вы полностью готовы к нашему грандиозному путешествию!

Когда Йоханнс рисует, у него есть несколько целей. Он нацелен на детали и проработку фокальных точек. Также, он хочет более точно определить формы, которые на его взгляд, недостаточно объёмны. Ему хочется усилить позу и композиционное течение объекта, используя для этого направление мазков (Клэр Вендлинг в совершенстве освоила этот приём, обратите внимание на направление штриховки в формах теней в её рисунках). Йоханнс, старается передать материалы, контролируя жёсткость краёв (в основном рисуя используя smudge-tool). Он хочет добавить зеркальные блики и нежную атмосферную перспективу. И наконец, усилить фокальные точки через Hue-intensity и Lens-focus. Он не хотел бы, чтобы это выглядело шаблонно, хотя на данный момент мы пришли к некой формуле. Йоханнс хочет подчеркнуть, он думает, что в процессе рисования, очень важно позволять себе отклоняться от лайнарта. Если вам кажется что-то неправильным, исправьте это. Моё рисование несколько хаотично, он же прыгает по всей картине одновременно, казалось бы без цели. На самом деле это не так, у него есть ясное представление о том, что он на самом деле делает. Йоханнс не может и не хочет делать этот этап механически, ему необходимо предоставлять интуиции и чувствам участвовать в этом процессе. Ему необходима неопределённость, чтобы найти удовольствие и насладиться своим творением.

How to Render: the fundamentals of light, shadow and reflectivity

Описание книги

This book is about the fundamentals of light, shadow and reflectivity; the focus is firmly on helping to improve visual understanding of the world around and on techniques for representing that world. Rendering is the next step after drawing to communicate ideas more clearly. Building on what Scott Robertson and Thomas Bertling wrote about in How To Draw: Drawing and Sketching Objects and Environments from Your Imagination, this book shares everything the two experts know about how to render lig.

This book is about the fundamentals of light, shadow and reflectivity; the focus is firmly on helping to improve visual understanding of the world around and on techniques for representing that world. Rendering is the next step after drawing to communicate ideas more clearly. Building on what Scott Robertson and Thomas Bertling wrote about in How To Draw: Drawing and Sketching Objects and Environments from Your Imagination, this book shares everything the two experts know about how to render light, shadow and reflective surfaces. This book is divided into two major sections: the first explains the physics of light and shadow. One will learn how to construct proper shadows in perspective and how to apply the correct values to those surfaces. The second section focuses on the physics of reflectivity and how to render a wide range of materials utilizing this knowledge. Throughout the book, two icons appear that indicate either “observation” or “action.” This means the page or section is about observing reality or taking action by applying the knowledge and following the steps in creating your own work. Similar to our previous book, How To Draw, this book contains links to free online rendering tutorials that can be accessed via the URL list or through the H2Re app. Книга «How to Render: the fundamentals of light, shadow and reflectivity» авторов Scott Robertson, Thomas Bertling оценена посетителями КнигоГид, и её читательский рейтинг составил 0.00 из 10.

Для бесплатного просмотра предоставляются: аннотация, публикация, отзывы, а также файлы для скачивания.

Custom shader fundamentals

These example shaders for the Built-in Render Pipeline A series of operations that take the contents of a Scene, and displays them on a screen. Unity lets you choose from pre-built render pipelines, or write your own. More info

See in Glossary demonstrate the basics of writing custom shaders, and cover common use cases.

For information on writing shaders, see Writing shaders.

Setting up the scene

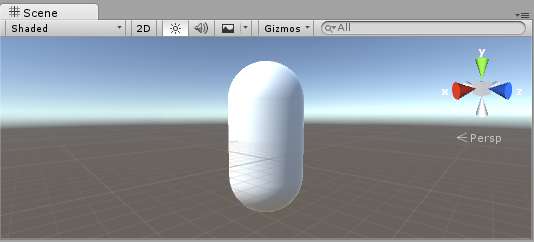

The first step is to create some objects which you will use to test your shaders. Select Game Object > 3D Object A 3D GameObject such as a cube, terrain or ragdoll. More info

See in Glossary > Capsule in the main menu. Then position the camera so it shows the capsule. Double-click the Capsule in the Hierarchy to focus the scene view on it, then select the Main Camera object and click Game object > Align with View from the main menu.

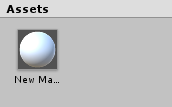

Create a new Material by selecting Create > Material An asset that defines how a surface should be rendered. More info

See in Glossary from the menu in the Project View. A new material called New Material will appear in the Project View.

Creating a shader

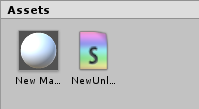

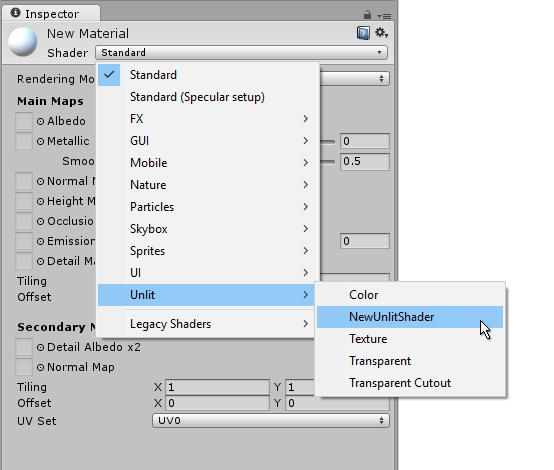

Now create a new Shader asset in a similar way. Select Create > Shader A program that runs on the GPU. More info

See in Glossary > Unlit Shader from the menu in the Project View. This creates a basic shader that just displays a texture without any lighting.

Linking the mesh, material and shader

Now drag the material onto your mesh The main graphics primitive of Unity. Meshes make up a large part of your 3D worlds. Unity supports triangulated or Quadrangulated polygon meshes. Nurbs, Nurms, Subdiv surfaces must be converted to polygons. More info

See in Glossary object in either the Scene A Scene contains the environments and menus of your game. Think of each unique Scene file as a unique level. In each Scene, you place your environments, obstacles, and decorations, essentially designing and building your game in pieces. More info

See in Glossary or the Hierarchy views. Alternatively, select the object, and in the inspector make it use the material in the Mesh Renderer A mesh component that takes the geometry from the Mesh Filter and renders it at the position defined by the object’s Transform component. More info

See in Glossary component’s Materials slot.

Main parts of the shader

To begin examining the code of the shader, double-click the shader asset in the Project View. The shader code will open in your script editor (MonoDevelop or Visual Studio).

The shader starts off with this code:

This initial shader does not look very simple! But don’t worry, we will go over each part step-by-step.

Let’s see the main parts of our simple shader.

The Shader command contains a string with the name of the shader. You can use forward slash characters “/” to place your shader in sub-menus when selecting your shader in the Material inspector.

The Properties block contains shader variables (textures, colors etc.) that will be saved as part of the Material, and displayed in the material inspector. In our unlit shader template, there is a single texture property declared.

A Shader can contain one or more SubShaders, which are primarily used to implement shaders for different GPU capabilities. In this tutorial we’re not much concerned with that, so all our shaders will contain just one SubShader.

Each SubShader is composed of a number of passes, and each Pass represents an execution of the vertex and fragment code for the same object rendered with the material of the shader. Many simple shaders use just one pass, but shaders that interact with lighting might need more (see Lighting Pipeline for details). Commands inside Pass typically setup fixed function state, for example blending modes.

These keywords surround portions of HLSL code within the vertex and fragment shaders. Typically this is where most of the interesting code is. See vertex and fragment shaders for details.

Simple unlit shader

The unlit shader template does a few more things than would be absolutely needed to display an object with a texture. For example, it supports Fog, and texture tiling/offset fields in the material. Let’s simplify the shader to bare minimum, and add more comments:

The Fragment Shader is a program that runs on each and every pixel The smallest unit in a computer image. Pixel size depends on your screen resolution. Pixel lighting is calculated at every screen pixel. More info

See in Glossary that object occupies on-screen, and is usually used to calculate and output the color of each pixel. Usually there are millions of pixels on the screen, and the fragment shaders are executed for all of them! Optimizing fragment shaders is quite an important part of overall game performance work.

When used on a nice model with a nice texture, our simple shader looks pretty good!

Even simpler single color shader

Let’s simplify the shader even more – we’ll make a shader that draws the whole object in a single color. This is not terribly useful, but hey we’re learning here.

This time instead of using structs for input (appdata) and output (v2f), the shader functions just spell out inputs manually. Both ways work, and which you choose to use depends on your coding style and preference.

Using mesh normals for fun and profit

Let’s proceed with a shader that displays mesh normals in world space. Without further ado:

Besides resulting in pretty colors, normals are used for all sorts of graphics effects – lighting, reflections, silhouettes and so on.

In the shader above, we started using one of Unity’s built-in shader include files. Here, UnityCG.cginc was used which contains a handy function UnityObjectToWorldNormal. We have also used the utility function UnityObjectToClipPos, which transforms the vertex from object space to the screen. This just makes the code easier to read and is more efficient under certain circumstances.

We’ve seen that data can be passed from the vertex into fragment shader in so-called “interpolators” (or sometimes called “varyings”). In HLSL shading language they are typically labeled with TEXCOORDn semantic, and each of them can be up to a 4-component vector (see semantics page for details).

Also we’ve learned a simple technique in how to visualize normalized vectors (in –1.0 to +1.0 range) as colors: just multiply them by half and add half. For more vertex data visualization examples, see Visualizaing vertex data.

Environment reflection using world-space normals

When a Skybox A special type of Material used to represent skies. Usually six-sided. More info

See in Glossary is used in the scene as a reflection source (see Lighting window), then essentially a “default” Reflection Probe A rendering component that captures a spherical view of its surroundings in all directions, rather like a camera. The captured image is then stored as a Cubemap that can be used by objects with reflective materials. More info

See in Glossary is created, containing the skybox data. A reflection probe is internally a Cubemap A collection of six square textures that can represent the reflections in an environment or the skybox drawn behind your geometry. The six squares form the faces of an imaginary cube that surrounds an object; each face represents the view along the directions of the world axes (up, down, left, right, forward and back). More info

See in Glossary texture; we will extend the world-space normals shader above to look into it.

The code is starting to get a bit involved by now. Of course, if you want shaders that automatically work with lights, shadows, reflections and the rest of the lighting system, it’s way easier to use surface shaders. This example is intended to show you how to use parts of the lighting system in a “manual” way.

The example above uses several things from the built-in shader include files:

Environment reflection with a normal map

Often Normal Maps A type of Bump Map texture that allows you to add surface detail such as bumps, grooves, and scratches to a model which catch the light as if they are represented by real geometry.

See in Glossary are used to create additional detail on objects, without creating additional geometry. Let’s see how to make a shader that reflects the environment, with a normal map texture.

Now the math is starting to get really involved, so we’ll do it in a few steps. In the shader above, the reflection direction was computed per-vertex (in the vertex shader), and the fragment shader was only doing the reflection probe cubemap lookup. However once we start using normal maps, the surface normal itself needs to be calculated on a per-pixel basis, which means we also have to compute how the environment is reflected per-pixel!

So first of all, let’s rewrite the shader above to do the same thing, except we will move some of the calculations to the fragment shader, so they are computed per-pixel:

That by itself does not give us much – the shader looks exactly the same, except now it runs slower since it does more calculations for each and every pixel on screen, instead of only for each of the model’s vertices. However, we’ll need these calculations really soon. Higher graphics fidelity often requires more complex shaders.

We’ll have to learn a new thing now too; the so-called “tangent space”. Normal map textures are most often expressed in a coordinate space that can be thought of as “following the surface” of the model. In our shader, we will need to to know the tangent space basis vectors, read the normal vector from the texture, transform it into world space, and then do all the math from the above shader. Let’s get to it!

Phew, that was quite involved. But look, normal mapped reflections!

Adding more textures

Let’s add more textures to the normal-mapped, sky-reflecting shader above. We’ll add the base color texture, seen in the first unlit example, and an occlusion map to darken the cavities.

Balloon cat is looking good!

Texturing shader examples

Procedural checkerboard pattern

Here’s a shader that outputs a checkerboard pattern based on texture coordinates of a mesh:

Then the fragment shader code takes only the integer part of the input coordinate using HLSL’s built-in floor function, and divides it by two. Recall that the input coordinates were numbers from 0 to 30; this makes them all be “quantized” to values of 0, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 2.5, and so on. This was done on both the x and y components of the input coordinate.

Next up, we add these x and y coordinates together (each of them only having possible values of 0, 0.5, 1, 1.5, …) and only take the fractional part using another built-in HLSL function, frac. Result of this can only be either 0.0 or 0.5. We then multiply it by two to make it either 0.0 or 1.0, and output as a color (this results in black or white color respectively).

Tri-planar texturing

For complex or procedural meshes, instead of texturing them using the regular UV coordinates, it is sometimes useful to just “project” texture onto the object from three primary directions. This is called “tri-planar” texturing. The idea is to use surface normal to weight the three texture directions. Here’s the shader:

Calculating lighting

Typically when you want a shader that works with Unity’s lighting pipeline, you would write a surface shader. This does most of the “heavy lifting” for you, and your shader code just needs to define surface properties.

However in some cases you want to bypass the standard surface shader path; either because you want to only support some limited subset of whole lighting pipeline for performance reasons, or you want to do custom things that aren’t quite “standard lighting”. The following examples will show how to get to the lighting data from manually-written vertex and fragment shaders. Looking at the code generated by surface shaders (via shader inspector) is also a good learning resource.

Simple diffuse lighting

The first thing we need to do is to indicate that our shader does in fact need lighting information passed to it. Unity’s rendering pipeline supports various ways of rendering; here we’ll be using the default forward rendering A rendering path that renders each object in one or more passes, depending on lights that affect the object. Lights themselves are also treated differently by Forward Rendering, depending on their settings and intensity. More info

See in Glossary one.

Here’s the shader that computes simple diffuse lighting per vertex, and uses a single main texture:

Diffuse lighting with ambient

The example above does not take any ambient lighting or light probes into account. Let’s fix this! It turns out we can do this by adding just a single line of code. Both ambient and light probe Light probes store information about how light passes through space in your scene. A collection of light probes arranged within a given space can improve lighting on moving objects and static LOD scenery within that space. More info

See in Glossary data is passed to shaders in Spherical Harmonics form, and ShadeSH9 function from UnityCG.cginc include file does all the work of evaluating it, given a world space normal.

This shader is in fact starting to look very similar to the built-in Legacy Diffuse shader!

Implementing shadow casting

Our shader currently can neither receive nor cast shadows. Let’s implement shadow casting first.

This means that for a lot of shaders, the shadow caster pass is going to be almost exactly the same (unless object has custom vertex shader based deformations, or has alpha cutout / semitransparent parts). The easiest way to pull it in is via UsePass shader command:

However we’re learning here, so let’s do the same thing “by hand” so to speak. For shorter code, we’ve replaced the lighting pass (“ForwardBase”) with code that only does untextured ambient. Below it, there’s a “ShadowCaster” pass that makes the object support shadow casting.

Now there’s a plane underneath, using a regular built-in Diffuse shader, so that we can see our shadows working (remember, our current shader does not support receiving shadows yet!).

We’ve used the #pragma multi_compile_shadowcaster directive. This causes the shader to be compiled into several variants with different preprocessor macros defined for each (see multiple shader variants page for details). When rendering into the shadowmap, the cases of point lights vs other light types need slightly different shader code, that’s why this directive is needed.

Receiving shadows

Implementing support for receiving shadows will require compiling the base lighting pass into several variants, to handle cases of “directional light without shadows” and “directional light with shadows” properly. #pragma multi_compile_fwdbase directive does this (see multiple shader variants for details). In fact it does a lot more: it also compiles variants for the different lightmap types, Enlighten Realtime Global Illumination A group of techniques that model both direct and indirect lighting to provide realistic lighting results.

See in Glossary (Realtime GI) being on or off etc. Currently we don’t need all that, so we’ll explicitly skip these variants.

Free Ebook How to Render: the fundamentals of light, shadow and reflectivity

Download and read it free How to Render: the fundamentals of light, shadow and reflectivity book as ebook, PDF, kindle ebook or MS Word. This book is the category Entertainment and Culture book. This book is very good, some individuals have actually downloaded and read as well as read the How to Render: the fundamentals of light, shadow and reflectivity right here. Click the picture or the link in this article to get How to Render: the fundamentals of light, shadow and reflectivity book free. Use the instructions listed below to download and read Entertainment and Culture book category.

Rating:

You could download How to Render: the fundamentals of light, shadow and reflectivity on your Kindle gadget, COMPUTER, phones or tablet computers. To obtain a free copy of How to Render: the fundamentals of light, shadow and reflectivity book, simply follow the directions provided on this page.

How to download and read How to Render: the fundamentals of light, shadow and reflectivity book?

Excellent testimonies have actually been given for the How to Render: the fundamentals of light, shadow and reflectivity book. This book is truly helpful and also absolutely add to our information after reading it. I truly want to read this book Entertainment and Culture. If you like How to Render: the fundamentals of light, shadow and reflectivity Book, kindly share this url in your social media sites.

Light and Shadow in Art – The Fundamentals of Light, Part 1: The Science & The Basics Made Clear

The Science & The Basics

I’m not sure many people fully appreciate the nature of what artists attempt to do each time we set out to render light and shadow in art. I know I haven’t, even when I’m in the middle of rendering, and I love light and shadow in art!

As I continue to dig into what light and shadow in art really is, I am awestruck and so thankful to all the scientists and artists who came before me—the giants upon whose shoulders we stand—because the subject of light and shadow in art is huge, and I am glad they already figured all this stuff out for us 😅.

It is difficult not to get philosophical here because what we are really doing when we render light and shadow in art is re-creating the properties and behaviors of light in a 2D space—and those behaviors and properties encompass several sub-branches of modern Physics, including: Quantum Physics, Modern Optics, Geometric Optics, and Physical Optics.

Let’s take a moment to appreciate the fact that different aspects of light behavior and properties come under several different categories of Physics that are each quite involved areas all their own.

That was my not-so-subtle warning that The Fundamentals of Light–light and shadow in art– gets quite technical.

The understanding we gain for our art is totally worth it, and we need three things for sure: 1) Patience, 2) Plenty of visual examples, and 3) More than one post to go through the massive amounts of information.

I hope you will hang in there with me as I break down the technical bits (that’s the patience part), I hope the examples and information I share help your practice, and that you’ll find it useful enough to look forward to the future posts in this series. Since this is the first, let’s start digging into to the science of light and shadow in art, shall we?

The Science—What is Light?

To understand how to render light and shadow in art we must grasp the concept of what light is and how it behaves.

Light is a type of energy created by the emission of photons within the electromagnetic spectrum. If that sounded like gobbledygook, fear not, I shall explain.

A photon is a “small bundle” of electromagnetic energy and the basic unit that makes up all light. Thus, photons are the building blocks of light.

Electromagnetic energy describes forms of energy that are reflected or emitted from objects as electrical and magnetic waves that can travel through space. The Electromagnetic Spectrum shown below describes these energies as frequencies and wavelengths.

The light effects we paint represent a fixed and narrow range of the Electromagnetic Spectrum called the Visible spectrum, which is a narrow group of wavelengths between approximately 380 nm (nanometers) and 730 nm.

As illustrated in the diagram above, The Electromagnetic Spectrum contains several other forms of light, however most of them are at frequencies we can feel but not “see”.

All light has both a frequency and a wavelength, and all light can behave as both a particle and a wave depending on the situation. In fact, both light and matter have particle-wave duality in their properties and behavior. It’s important for artists to understand this duality because it affects our thinking and problem solving regarding light at different stages during rendering.

When we begin to invent our images we must also invent our lighting. When we are mentally calculating the direction of our light source, its reflections, and fall off, it is helpful to think of light as particles, or rays, that travel in straight lines.

This helps us figure out how much of our object will be lit, how to place the form shadows and cast shadows, and where the bounce light will land. When objects are opaque, I have found considering light primarily as rays helps me best determine how to render the light.

When objects are translucent, transparent, or have variable reflectivity, things start to get more complex because light is not simply being absorbed and reflected but also transmitted through the object. Transmission of light through objects gives us more to consider and calculate because it gives us more to paint, like subsurface scattering, refraction, and more reflections.

Let me put your mind at ease and say it is not necessary to do any complex mathematic calculations to paint these effects, just some additional concepts to understand and visual calculations to make.

When we think about reflection, refraction, and absorption, it helps to think of light first as a particle or ray (for determining the light’s intensity, direction, and bounce) and then as a wave—for determining which wavelengths are reflected off, absorbed by, and/or transmitted through the object and the ground.

That was a huge mouthful, I know. I will be going over all of these more nuanced areas in other articles in this series.

Understanding the particle-wave duality of light begins to give us a clear view of how light’s behavior changes as it interacts with different materials. Watching the videos below helped me gain a clearer understanding of this concept, and I hope you find them useful, too.

As we bring together the elements we need to understand, we start to define the contours of The Fundamentals of Light (light and shadow in art) so that we can start filling in details and particulars—and don’t worry, there will be photographic examples and demos so all of this becomes more clear.

Properties of Light & Matter for Artists

I know this has been a little science-heavy so far, and that’s intentional. It is how I make sense of complex topics, and I hope you find it helpful. Now that we’ve covered the basics of what light is, I’ll change things up a bit to keep everything digestible. I’ll cover a little science and do some explaining, and then use photographic examples or demos to clarify how the information helps in creating art.

Next, let’s dig into the properties of light, but first I want to give you a list of all the properties to keep in mind whenever it’s time to render light. This is a list according to me, and they’re based on my experience rendering light in both 2D (Photoshop) and 3D (Maya).

| Light Properties | Matter Properties |

| Number of Sources | Form/Shape |

| Type of Light(s) | Local Color |

| Size of Source(s) | Material Type |

| Distance from object/picture plane | Density |

| Angle/Height of Source(s) | Reflectivity |

| Temperature/Color | Transmission |

| Exposure/Intensity | Refractive Index |

| Fall Off | Emission |

Some of these are straightforward, so let’s talk about those briefly. The number of light sources is an important consideration because we need to know how much light information we’re working with. More light sources in a scene makes for a brighter image, but how each source affects the picture plane depends on all the other properties on the list.

The size and angle/height of each source are also straightforward properties and they ask questions like: Is a light source large, small, or medium? Do several small lights make up one larger source because of how closely grouped they are? Do these sources sit high or low on the picture plane? Are they even visible in the image, or are they shining from somewhere out of frame?

Under properties of matter, shape, form, local color, and material type are the most straightforward. We must know what shapes and forms make up the volume of the objects we’re rendering, and we need to know what color and material type they are. After all, there is quite a difference between painting a shiny chrome ball and painting a shiny colored plastic ball. Sure, they’re both shiny; but one is metal and ridiculously reflective while the other is plastic, softer, and much less reflective.

The Two Ways Our World is Lit

Despite all the science, properties, and moving parts involved with understanding how objects are lit, there really are only two ways anything receives light in our world: directly or indirectly.

Objects are either lit directly by a light source or indirectly by reflected light when the rays from the source bounce off some surfaces and objects to illuminate others. This kind of indirect lighting is also called Ambient Light and it is much weaker in comparison to direct light. Most lighting schemes will involve both direct and indirect lighting.

Next, we’ll go over the categories that light sources fall into.

Properties of Light – Types of Light Sources

There are 3 types of light sources:

Key Light

A key light is the strongest light source in your scene. It defines the emotional impact of the scene and is the primary descriptor of forms and drama. When you decide how to “key” your scene, you are choosing the overall mood and tonal range that will define it.

Fill Light

A fill light is not as bright as a key light and is often softer and a lot darker. Fill lights support your scene and subjects by adding light and color information in the shadows, which can illuminate an area of interest you wish the viewer to see or just provide added interest or balance to your scene. Fill light can be ambient (reflected) light, as I’ve done in my examples below, or it can come from an additional light source(s).

Rim Light

A rim light travels the outer edges of objects. Rim light helps define shapes, add dramatic appeal, and can be a helpful tool for adding compositional information and/or emotional impact.

No matter what kind of mood a story or scene calls for, any lighting scheme will have at least a key light and, likely, some combination of all three light source types.

Okie dokie, how’re you doing? I know this has been a lot to get through, and I hope you’re still hanging in there with me. Deep breaths, we’ve got this!

Now, it’s time to go over some terminology to help keep things clear as we continue to move through the Fundamentals of Light (light and shadow in art).

Defining Terminology + Sphere Tests

Think of this as the glossary section of this post. Here I’ll define the frequently used terms that will show up quite often from now on in both my writing and the call-outs in demos and examples.

Light Source

Anything that creates and emits light. Light sources can be natural, like the sun, moon, and fire, or artificial, like lamp posts, flashlights, and device screens.

Light Direction & Angle

The orientation of a light source relative to the picture plane. For example, low and out of frame on the left, or mid-level and in frame on the right.

Exposure

The intensity or strength of a light source. A high exposure light source makes for a brighter, “high key” scene, while a lower exposure light will make a scene appear less bright. I tend to use exposure and intensity interchangeably.

Center Light

The area of a form receiving most of the light; the lit side of a form.

Highlight

The brightest area on a form. This is usually a small area that is receiving the most direct light and reflecting a bit of it back.

Half Tone

The area on a form that has begun to turn away from the light source, resulting in a transition area of light to shadow. This area is receiving some light, but not nearly as much as the parts of the form facing the light source more directly.

Reflected/Bounce Light

Light that bounces off a surface and then lands on another form or surface is Reflected or “bounce” light. Reflected light is much weaker than direct light and can occur on any part of a form, except occluded areas.

Terminus/Terminator

The point at which light cannot land on a surface. This is where the shadow side of the form begins.

Shadow Core

The darkest part of the form shadow. The shadow core on a sphere typically looks like a dark band right next to the terminus, a clear separator between the light and shadow. The core shadow is also the part of the form shadow least affected by reflected light.

Form Shadow

The areas of a form that are in complete shadow and receive no direct light.

Occlusion Shadow

Occlusion shadows are the darkest areas in shadows and on/within forms where absolutely no light can reach. When something is occluded it is completely obstructed or blocked, so when light is occluded you have complete darkness.

We see occlusion most often in narrow areas right beneath forms before the cast shadow begins, and with narrow openings, cracks, and crevices of surfaces/forms. Occluded areas are not sufficiently open enough to the environment to receive any light, so there is only shadow.

Cast Shadow

Cast shadows is created when an object’s form blocks light. Objects block light adjacent to themselves and in the shape of their contours. There are three distinct parts to a cast shadow, the Umbra, Penumbra, and Antumbra. Much of the time, in art, we are only painting an umbra and penumbra. When multiple light sources of different intensity and direction/angle are involved, we begin to see examples of all three parts of a cast shadow.

Now, I’m going to show a few sphere test examples to visually illustrate the terms above so we can make practical sense of all you’ve been reading.

The Distance of Light Sources & Why It Matters

Each property of light and shadow in art plays a role in affecting the mood of our scene and the light effects we paint. The appearance and quality of shadows are determined by the light and forms that cast them. How near or distant a light source is to an object has a significant impact on the appearance of an object’s form shadows and cast shadows, so let’s get into that next.

Distant Light Sources (Sunlight, moonlight, spotlights, etc)

We can group lights into categories based on their characteristics, like size, distance, and how intense they are to get a starting place for how those lights would interact with the objects in our scenes.

Distant light sources are things like sunlight, moonlight, and powerful spotlights like those in stadiums and theaters. Distant lights tend to:

As one example, we know the sun is a huge, very distant, powerful light source, and from observation we know that light from the sun strongly illuminates everything it reaches. That means light is bouncing around everywhere in our atmosphere and reflecting a lot of light, so we can expect brighter and more colorful shadows when the sun is involved.

Playing with exposure also makes a big difference, so an overcast grey sky lowers the exposure, diffuses the light, and makes the sunlight seem much less energetic than a clear and cloudless sky, and creates lighter, softer, and less colorful shadows.

The Sun is also larger than our Earth, and any object we would light with it, so we must also consider the sun as an “oversized” light, which we’ll get into in a minute.

Nearby Light Sources

Nearby light sources are things like lamps, candles, device screens and monitors, lighters, matches, lanterns, etc. Nearby light sources tend to create:

When nearby light sources are also quite small (like candlelight or a lighter), they tend to cast hard-edged cast shadows. They present an additional composition challenge because they can become distracting if not handled carefully. Nearby light sources tend to become a focal point in a scene, so it’s important to be mindful of that and use it to your advantage for your chosen lighting scheme and compositional design.

Oversized or Diffuse Light Sources

Examples of oversized or diffuse light sources are the entire sky on an overcast day (sky light), light coming through large windows, and any light that is scattered by being translucently covered or blocked (like a paper lantern, a light sheet or cloth, an umbrella, or frosted glass covering for light bulbs). Oversize or diffuse light sources tend to:

In the case of light sources that are larger than the objects they illuminate, the light rays are travelling out in random directions, reflecting off the atmosphere and other objects and surfaces, and filling in the shadows, which softens them. Shadows become softer edged because light does not reach each part of the shadow area equally, and because the object blocks (occludes) part of the light area behind it.

Ambient Light

Ambient light is created when light from a source is reflected off the ground, other objects, and the environment. It is possible for objects to be exclusively lit by ambient light, but a key light (which is usually a direct kind of light) is still needed to emit the light that will be reflected.

Terms like indirect light, reflected light, and bounce light all mean the same thing: they are all ambient light. Ambient light is most noticeable in shadows because of the contrast, but it is present whenever and wherever reflected light lands on an object or surface.

Light rays lose most of their strength and brightness (90%) with each bounce, and they are bouncing around multiple times. This loss of strength is why ambient light is generally weak and cannot reach into occluded areas.

You may have come across the term ambient occlusion, especially as it relates to lighting in 3D modeling apps like Maya and Zbrush. In drawing and painting, if zero light can reach an area, I simply refer to this as an occlusion shadow or an occluded area.

For a bit more on ambient light and ambient occlusion, here’s a video by Marco Bucci (awesome artist!) that I found helpful.

Light Direction & Angle: How They Affect A Scene

In any lighting scheme, cast shadows are a compositional and mood element that should be considered and planned. Choosing the light’s direction and angle is an important step in setting the emotional tone of a scene as well as defining forms and helping viewers to understand how to react to what they are seeing. Cast shadows can add drama and mystery to a scene, particularly when the object or character casting the shadow is off-camera.

Different light directions and angles offer a variety of mood options, and I’ve listed a few here:

How you choose to render the light and shadow in art you create will always depend on the position and point of view of the audience, and the message that needs to be conveyed.

The Fundamentals of Light (Light and Shadow in art)—Breaking Down The Parts

Even though we learn in steps and stages, I find it helpful to get the “lay of the land” because it provides a road map, and it’s nice to at least have some idea of what we’re doing, right? With that in mind, I have listed the major headings that are part of studying The Fundamentals of Light (light and shadow in art) and broken out some detail for the area we’ve covered today.

Next Time: The Fundamentals of Light, Part 2!

Take a moment to think of your absolute favorite treat for relaxing and pampering yourself. See it, visualize it in your mind’s eye. Now…get yourself that treat! You have just made it through a massive amount of information in a relatively short(ish) amount of time.

Thank you for hanging in there with me to learn about light and shadow in art! I’ve tried to keep things clear and concise, but I know this was a lot to take in. I commend you, I thank you, and I am sending you virtual high fives and fist bumps!

Congratulations! You got through an intro to light and shadow in art!

We need some forms before we render light and shadow in art, so if you need guidance in that area I have some articles covering Form and The Fundamentals of Art to help.

The next couple of articles in my Fundamentals of Light series will cover exposure and fall off, and then absorption, reflection, and refraction of light wavelengths.

If I’ve confused you or you have questions, or if I’ve gotten anything wrong, please message me in the comments and I’ll do my best to clear things up.

I hope you’ll join me for those as well.

Take care and happy drawing with light and shadow in art everyone!

Источники информации:

- http://knigogid.ru/books/5504-how-to-render-the-fundamentals-of-light-shadow-and-reflectivity

- http://docs.unity3d.com/Manual/SL-VertexFragmentShaderExamples.html

- http://www.sites.google.com/site/wcbbook/How-to-Render-the-fundamentals-of-light-shadow-and-reflectivity

- http://cecelyv.com/light-and-shadow-in-art/