How to take smart notes

How to take smart notes

How To Take Smart Notes by Soenke Ahrens

This book that talks about Luhmann’s note-taking system and its utility in writing.

Niklas Luhmann, a 20th-century sociologist, isn’t the name that the world beyond sociologists much discusses. His work wasn’t about how to search alien lives, or how to dissect the DNA, or how to create new particles, or how to build long-lasting habits. His contributions aren’t as celebrated as they should be.

But people are slowly learning about this freakishly productive, geeky personality. His note-taking system, named Zettelkasten (translates to slip box in English), helped him to write nearly 400 scholastic articles and 70 books during his 40 year-long careers.

What was the X-factor in his system skyrocketed his productivity? How did he manage it? Why is it so relevant in the 21st century?

The system Luhmann crafted had extraordinary simplicity and customizability. He credited his sociology wizardry to his Zettelkasten. When asked how he generated so many original ideas and credible work, Luhmann said, “I, of course, do not think everything by myself. It happens mainly within the slip-box.”

Sociologist Dr. Soeke Ahrens discussed Luhmann’s Zettelkasten in his book ‘How to Take Smart Notes’. He also attempted to enthuse the readers to adopt the system to boost their writing productivity.

In this article, I’m trying to delineate a few takeaways from the book and offer some criticism on why it could be better. I’m refraining from elaborating how the set-up works as the description is already available at zettelkasten.de.

Takeaways

Firstly, taking notes is essential. Crafting ingenious academic or nonfiction writing, that inspires others, needs a collection of concisely taken notes. Devouring all the information, interlinking, and produce innovative ideas — all inside the brain? Too audacious to think. An external note-taking system helps to store notes and ideas, freeing up the brain to process them. Zettelkasten is the analog ‘hard drive’ that stores the notes and allows the brain, the ‘biological RAM’, to think.

Secondly, don’t categorize notes. The customizability of Luhmann’s system lied in the idea that he never categorized his notes by topic or chapters. Categorization and hierarchy in notes cease that simplicity. Luhmann used to put coordinates on his note cards and link them bidirectionally. In internet terms, it’s equivalent to backlinks. Notes, added to the system, build up to topics and even chapters, through interconnection and cross-linking.

Well, that’s it. Those are 5 key pieces of advice that I found useful. Whatever the software or the analog system is, Zettelkasten can be simulated in every one of them. A new software Roam Research is around the corner and that builds upon the principles of Luhmann’s slip-box.

Criticism

Apart from the aforementioned takeaways, I noted a few drawbacks of the book that are worth talking about. The author knows what he’s discussing. But I feel that the way he’s talking failed to deliver the promise of the title.

First, the book should have elaborated on the nitty-gritty details of the slip-box set-up. That was missing. After reading the entire book, my knowledge about Zettlekasten was the same as before I read it. The author swerved away from the main topic and described processes of writing itself instead of note-taking.

Second, ideas are made interesting and relatable by examples and anecdotes. Neither of these was an inadequate count in the book. An observable amount of paraphrasing and repetition of similar ideas got me bored, often.

Third, intertwined ideas seldom had anything in common. A thick proportion of the book contained advice about how to write and why should we write. Zeigernick effect, the process of flow, decision-making, attention switch — these were some ideas that I found little relevance towards note-taking.

This book had a great potential to bring an age-old productivity hack to the 21st century. Unfortunately, the transition didn’t happen with complete rigor. The book left me crestfallen after flipping the last page of my ePub book.

Final words

In a nutshell, the book has a few invaluable suggestions and advice. Those can help the reader overhaul their note-taking system. But also, the author spent an unreasonable amount of time explaining and talking about little relevant ideas and concepts pertaining to writing habits.

The ideas I outlined can actually change the perspective of any writer, be an academic or a nonfiction writer. The cyclic nature of writing, a requirement of external scaffolding, elimination of categorization — can be a game-changer for those who would never sit in front of a blank screen again.

Zettelkasten is a powerful note-taking method and Luhmann harnessed its complete potential. Its significance lies in its successful implementation. Interested in trying out Zettelkasten? Start from scratch, build up notes, and exploit the takeaways to master the craft of note-taking. Writing will automatically follow.

How to take smart notes

While there are hundreds of thousands of books on the generic topic of writing, very few concerns themselves with note-taking—perhaps because it’s not considered an intellectually challenging task by many, or perhaps because many people don’t realise how bad they are at taking notes.

Looking at a blank page and struggling to find inspiration? Experts will tell you to brainstorm or do some more research. But what if you don’t know where to start?

This is a problem you can ensure you will never face again if you learn how to take smart notes. In his eponym book, Dr. Sönke Ahrens shares the simple method used by German sociologist Dr Niklas Luhmann to publish more than 70 books and nearly 400 scholarly articles in his lifetime. Talk about being prolific!

The method is called the Zettelkasten, and despite its scary name—which means “slip box” or “card index” in German—it’s an incredibly simple and powerful way to take notes so you become more productive and more creative.

Dr Luhmann had two boxes with index cards: the first one where he put literature notes (when reading research papers), and the second one where he put his own thoughts and ideas. Each card has an identifier which allowed Luhmann to interlink the cards together, and there is an index of all topics covered in the slip box with the corresponding cards’ identifiers. The index was an entry point to explore a particular theme.

Here is the exact process he used to write his research papers.

You can discard the fleeting notes once they have been turned into permanent notes. Then, go to your slip box and look at previous permanent notes. Interlink your new permanent notes with the existing ones. Luhman used a simple indexing system where each card was numbered in a way that allowed him to follow the “idea trail”—today we have digital tools allowing us to interlink our notes in a much easier way. Roam is great for such a use case.

Make sure to write your notes in a way your future self will understand. If you go back to old notes and don’t understand what exactly you were thinking—the exact thought process and context—when you wrote it down, this note-taking system won’t work as intended.

After a while, you will start seeing patterns emerging in your notes. These patterns—and not the raw, fleeting notes you took in the beginning of the process—will form the basis of your original work.

You only need a few things in your toolbox to make use of this system:

Getting these tools ready shouldn’t take more than ten minutes. Remember that the tools are just that—tools. What really matters here is the process of constantly feeding your slip box with ideas written in your own words, and interlinking these ideas so you can see patterns emerge and generate ideas of your own.

“Imagine if we went through life learning only what we planned to learn or being explicitly taught,” writes Dr. Sönke Ahrens in his book. The Zettelkasten allows you to form new ideas without already knowing exactly what it is you are looking for. It’s a wonderful way to explore your curiosity and increase your creativity.

Join 40,000 mindful makers!

You’ve reached the end of the article. If you learned a thing or two, you can get a fresh one in your inbox every week. Maker Mind is a weekly newsletter with science-based insights on creativity, mindful productivity, better thinking and lifelong learning.

As a knowledge worker, your brain is your most important tool. Work smarter and happier by joining a community of fellow curious minds who want to achieve their goals without sacrificing their mental health. You’ll also receive a guide with 30 mental models to make the most of your mind!

One email a week, no spam, ever. See our Privacy policy.

Как вести «умные заметки»: обзор метода по книге Зонке Аренса

Эта статья — пошаговая инструкция метода «умные заметки» из книги Зонке Аренса «Как делать полезные заметки».

В своей книге Зонке больше пишет о чтении и мышлении, нежели о конкретных физических действиях. Чтобы лучше понять метод, я выписал из книги только практические советы по ведению заметок и сгруппировал их в единую инструкцию. Поэтому в этой статье не будет о том, зачем вести картотеку и как ей пользоваться, а только что делать и как.

Постарался писать как можно меньше отсебятины, чтобы не исказить суть. Но, в то же время, написал немного по-своему, чтобы смысл метода был понятен даже тем, кто ещё не читал книгу.

«Умные заметки» в шести пунктах

Сила «умных заметок» в простоте. Весь процесс состоит из нескольких простых действий:

Дальше расскажу о каждом пункте подробнее.

Записывайте всё, что приходит в голову

Всегда записывайте каждую мысль или идею, которые приходят вам в голову, или интересную информацию, которую не хотите забыть.

На этом этапе даже не нужно задумываться о пользе заметки. Не ломайте голову, просто запишите, чтобы хорошая мысль не пропала вдруг даром.

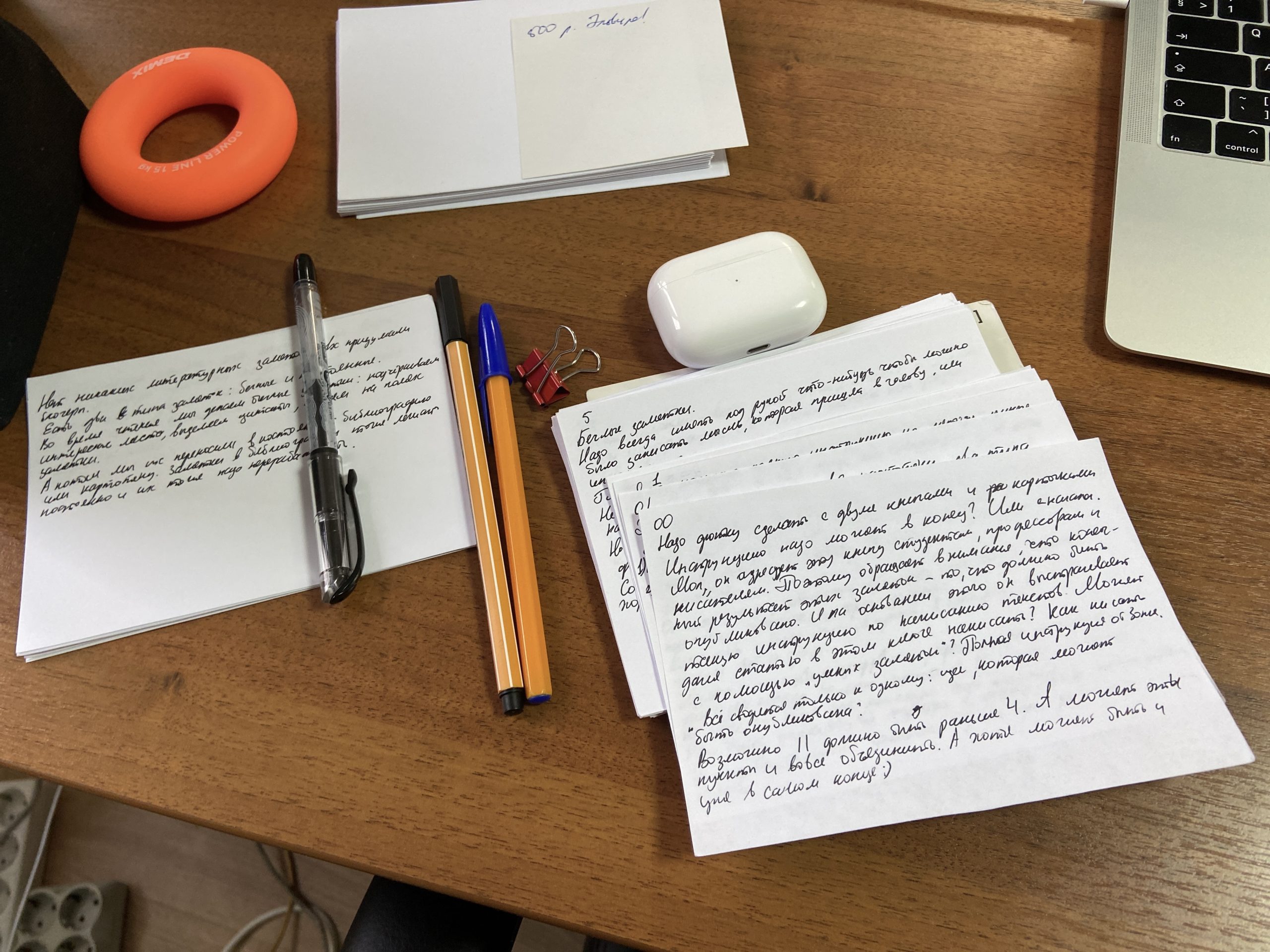

Всегда держите под рукой что-нибудь, чем можно будет записать вашу идею. Это может быть блокнот или приложение Заметки на айфоне. Я, например, держу на рабочем столе стопку обычных бумажных карточек A6. А если надо записать что-нибудь на улице или в метро, закидываю мысли во Входящие в Things или наговариваю на диктофон в Apple Watch.

Не важно, какой именно инструмент для записи выберете вы. Главное, чтобы идею или мысль можно было записать быстро, не отвлекаясь от работы или чтения.

Не надо ломать голову над формулировками и стараться писать красиво. Эти записи — просто напоминания о мыслях, идеях или информации, а не полноценные заметки.

По этой же причине, не нужно думать об организации таких заметок. После обработки, их можно будет удалить или переместить в архив.

Делайте заметки во время чтения

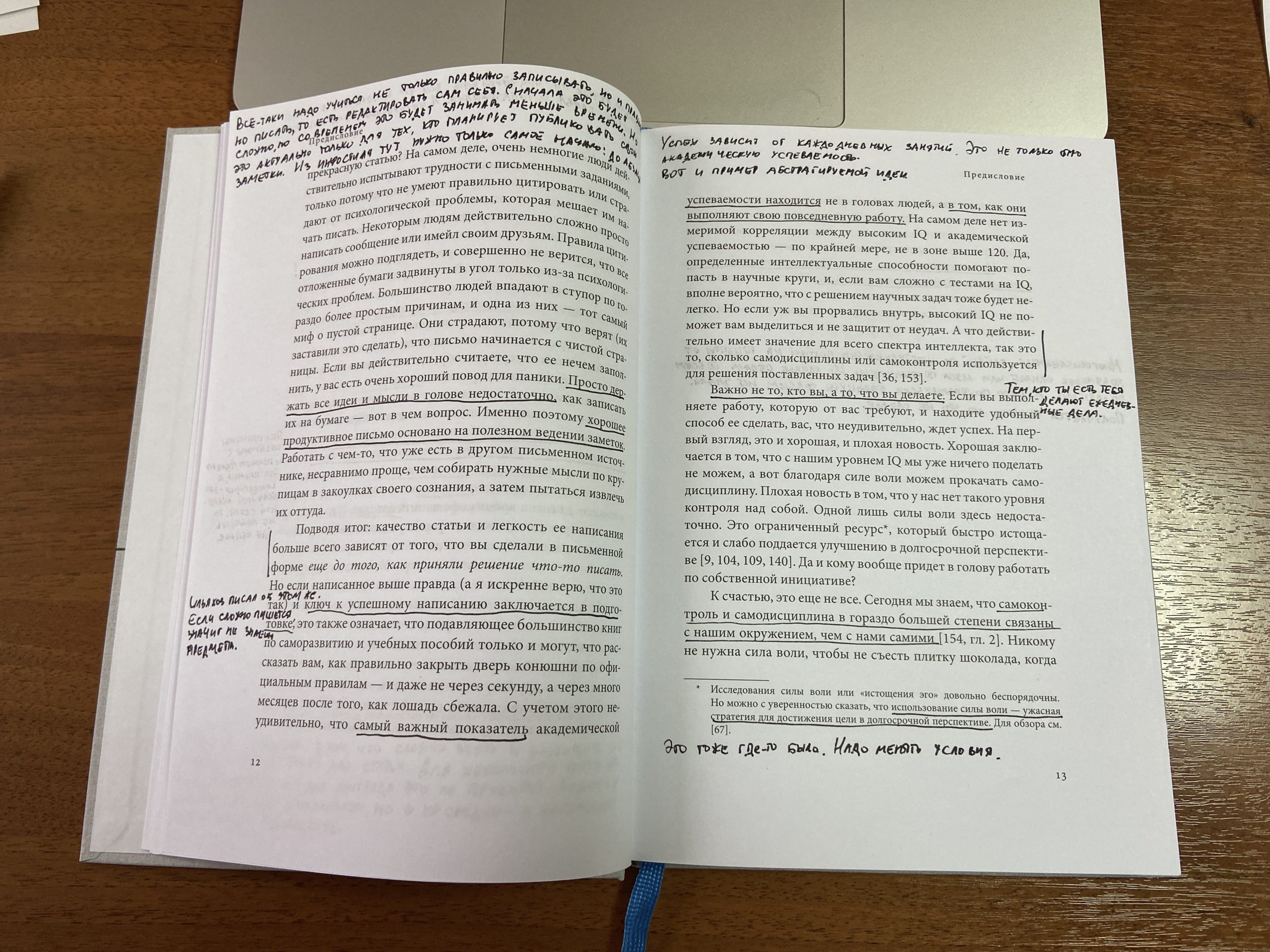

Отмечайте интересные места в книге, которую вы читаете. Это может быть информация, идеи или цитаты, которые могут пригодиться в будущем.

Делать такие заметки можно разными способами. Вот, например, как это делал Луман. Он брал карточку и писал на одной стороне информацию о книге: название, автора и год публикации. На другой стороне он записывал идеи из книги с указанием страниц, на которых он их прочитал.

«У меня всегда под рукой листок бумаги, на котором я записываю идеи определённых страниц. На обороте я записываю библиографические данные.»

В электронных читалках можно выделять текст и делать заметки. А потом экспортировать свои пометки в текстовый формат с помощью сервисов типа Readwise.

Я читаю, в основном, бумажные книги и обхожусь только ручкой, без карточек или блокнотов. Если мне попадается интересная идея или в голову приходит какая-то мысль, я подчёркиваю строки или пишу прямо на полях книги.

Переносите идеи из книг и свои мысли в картотеку

Главная идея «умных заметок» Зонке и цеттелькастен Лумана — хранить все свои заметки в одном месте в едином формате. Для этого надо регулярно, идеально — раз в день, переносить все свои телефонные заметки, диктофонные записи, подчёркнутые предложения на страницах и мысли на полях книг, в одно место — в картотеку.

У Лумана было две картотеки: библиографическая и основная. В первой он хранил заметки о содержании книг и других источников, а в основной картотеке собирал свои мысли, идеи и комментарии к прочитанному.

Библиографические заметки — это не сборник цитат, а краткая перепись идей и информации из текстов. Зонке советует писать кратко, быть предельно избирательными в выборе информации и записывать идеи своими словами.

Сюда же надо заносить информацию и идеи из статей, подкастов, видеороликов, лекций и других источников. Все чужие мысли, которые могут быть полезными в работе или учёбе, должны храниться в библиографии.

Для удобства, лучше использовать специальные библиографические менеджеры. Один из самых популярных вариантов — Zotero. В нём удобно собирать информацию о прочитанных книгах, статьях, просмотренных видео и даже сохранять ПДФ-файлы.

В бумажной картотеке можно делать так же, как Луман — записывать идеи из книг на отдельной карточке. Или просто составить список источников: книг, статей, видео, на которые ссылаться в основной картотеке. В таком случае на карточке из основной картотеки делается сноска вида «Автор/Год». Например, ссылка на книгу «Как делать полезные заметки» будет выглядеть как «Зонке/2022».

Библиографические записи — это всего лишь справочник чужих идей. А вот главная картотека — это хранилище собственных мыслей.

Вот как составлял эти заметки Луман.

В конце дня он просматривал свои черновики и записи, которые сделал во время чтения. Он не просто переписывал их, а размышлял о том, как новые заметки могут быть связаны с остальными записями в картотеке.

Что делает новая информация? Она дополняет, противоречит, исправляет уже имеющуюся? Какие вопросы возникают? Можно ли объединить эту мысль с другой идеей?

Зонке пишет, что идеи из книг надо не копировать, а переносить из одного контекста в другой. Для этого надо выделить суть идеи, очистить её от подробностей, а потом перенести в контекст своих мыслей, интересов и работы.

Зонке, как и Мортимер Адлер в книге «Как читать книги», сравнивает этот процесс с переводом иностранной речи. Опытный переводчик может пожертвовать точностью перевода, использовав другие слова, чтобы точнее передать суть сказанного. Кстати, переводчику книги «Как делать полезные заметки» этого сделать не удалось. А жаль.

Ещё один способ добавить идеи в контекст своей картотеки, он же и самый простой, — спросить себя, почему эта идея важна для вас и ваших мыслей.

Полезно записывать не только идеи, но и вопросы, которые возникают при чтении и размышлении. Любой факт, идею или информацию можно уточнить и развить вопросами: «Почему? Зачем? Ну и что?»

Про оформление заметок в картотеке уже писали, и не раз. Основной принцип — одна заметка для одной идеи. Пишите полными предложениями, с указаниями источников, с ссылками. Представьте, что этот текст увидят другие люди, а не только вы.

Многие доводят этот принцип до абсолюта и делают свои заметки публичными. Самый известный пример такой картотеки — заметки Энди Матушака.

Как редактор, добавлю, что для ведения картотеки пригодится навык писать в инфостиле: просто, понятно и лаконично. Особенно это пригодится, если вы планируете использовать заметки для будущих публикаций.

Создавайте последовательности заметок

«Идея не в том, чтобы собрать, а в том, чтобы развивать идеи, аргументы и дискуссии».

Последовательность заметок — это цепочка записей по одной теме, собранных в определённом порядке. Луман брал только что созданную заметку и искал в картотеке уже существующую, для которой новая запись могла бы стать аргументом, предпосылкой, уточнением или комментарием. После этого он помещал заметку за одной или несколькими связанными заметками. Если запись была никак не связана с другими, то он добавлял её просто в конец всей картотеки.

Таким образом, Луман выстраивал в своей картотеке последовательности карточек, которые развивали разные идеи и ветки размышлений. Из таких последовательностей заметок получались уже практически полностью готовые черновики для будущих статей или книг.

Последовательность заметок также помогает увидеть пробелы в аргументации, неотвеченные вопросы, спорные моменты. Это очень полезно для учёных и писателей.

Порядок заметок закреплялся с помощью особой последовательной нумерации. За заметкой 21, шла заметка 22. Если новую заметку нужно было добавить между этими двумя, ей присваивался номер 21a и так далее. Номера могли быть сколько угодно длинными, как например 21/3a1p5c4fb1a.

В электронной картотеке такие последовательности можно выстраивать с помощью ссылок.

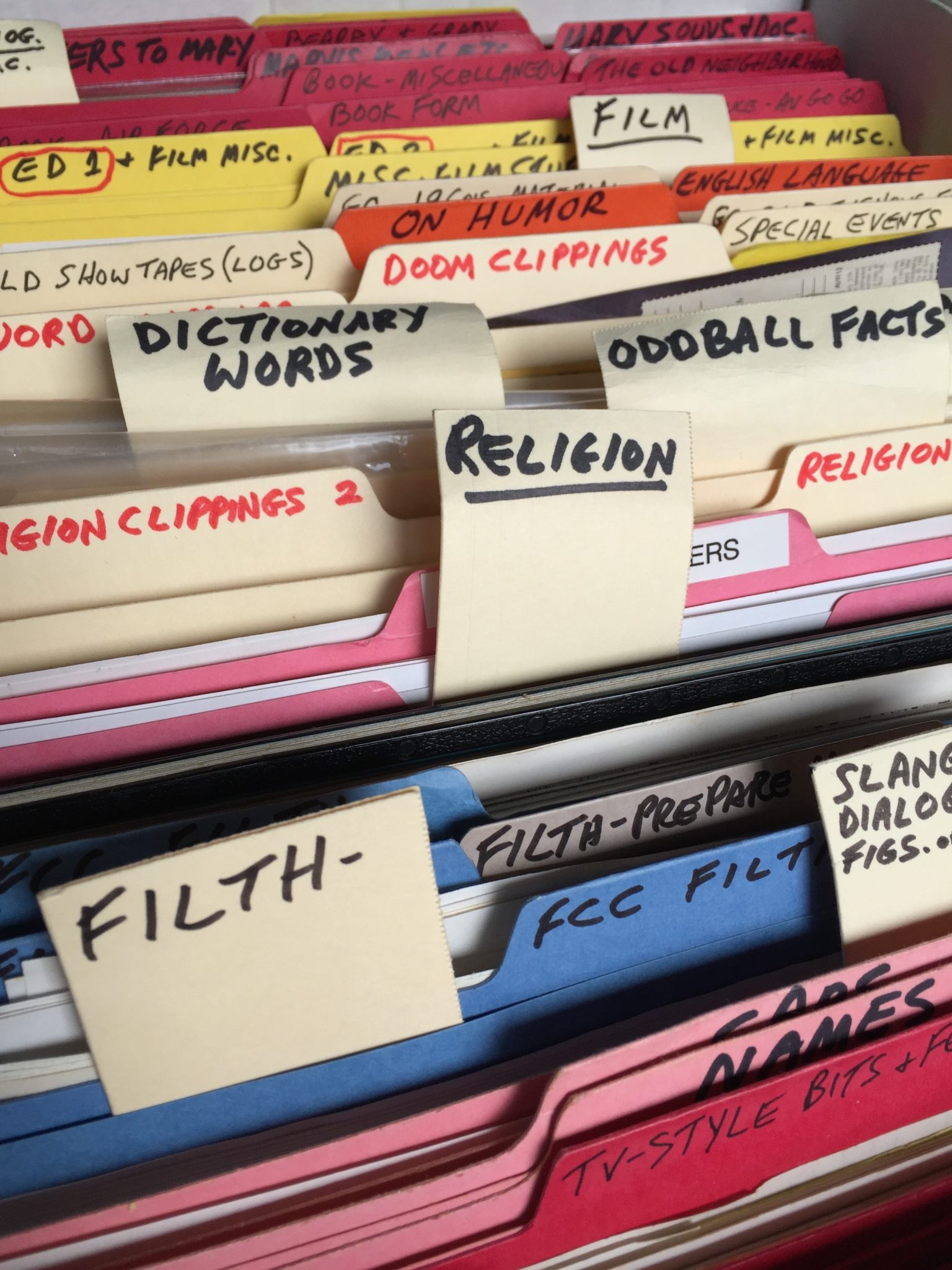

Такая система организации принципиально отличается от большинства методов ведения заметок. Как, например, организует заметки американский писатель-стоик Райан Холидей? Если ему в голову приходит какая-то идея или он находит в книге интересную цитату, Райан записывает информацию на каталожной карточке и пишет в правом верхнем углу тему. Заметку он просто добавляет в стопку других карточек по этой же теме.

Такой же подход можно использовать в электронной картотеке, проставляя к заметкам теги или собирая их в категории.

Но тематическая организация, с помощью папок или тегов, со временем приводит к проблемам. Под некоторыми тегами может скопиться очень много заметок и в них будет сложно найти нужную. А если добавлять новые темы, то их может стать так много, что придётся каждый раз ломать голову над тем, к какой теме стоит отнести новую заметку.

Делайте ссылки между заметками

После того, как вы добавили заметку в картотеку, надо подумать над ссылками на другие заметки.

Ссылки между заметками важнее, чем ссылки из указателя на заметку.

Ссылки между записями — ещё одно отличие «умных заметок» от других методов ведения картотеки. Такие ссылки указывают на связи между заметками: явные и не очень.

Если в заметке упоминается какой-нибудь термин или человек, можно поставить ссылку на соответствующую заметку. Это похоже на ссылки в Википедии.

Переходя по таким ссылкам, можно находить совершенно неожиданные идеи и мысли, о которых вы, возможно, уже и не помните. Наверняка, многим знакома ситуация, когда начинаешь читать статью о русско-японской войне, а через пару десятков переходов по ссылкам оказываешься на странице, посвящённой распаду Битлз. Читаешь и думаешь: «Как я здесь оказался?».

Но куда полезнее находить связи между, казалось бы, несвязанными идеями и темами. Такие ссылки помогают находить новые идеи, создавать то, чего раньше не было.

Создание таких ссылок требует серьёзного подхода и размышления, поэтому тут не помогут автоматические решения, которые предлагают Obsidian или Roam. Эти приложения сами находят упоминания о страницах, даже если вы не поставили ссылки на них.

Ссылки между страницами — не рутина, а результат размышлений и неожиданных озарений. Найти эти связи сложно, но это делает их более ценными и полезными для поиска новых идей и писательства.

Убедитесь, что сможете найти нужную заметку

Для того, чтобы найти нужную заметку, используйте указатель, индекс. Это список ключевых слов со ссылками на нужные заметки.

Луман печатал свой указатель на карточках. А в цифровой картотеке можно использовать теги.

Не надо стараться отметить в указателе все заметки по теме. Всё, что нужно от списка ключевых слов, это точка входа в нужном месте картотеки. А найти другие заметки можно будет с помощью ссылок между ними.

Если по какой-то теме у вас собралось много последовательностей записей по смежным темам, можно создать отдельную заметку с перечнем подтем. На такое «оглавление» и может вести ссылка из указателя.

Не надо особо расписывать о чём идёт речь в этих темах. Достаточно двух-трёх слов или одного предложения, как в оглавлении в книге.

Например, ключевое слово «картотека» может ссылаться на заметку со списком таких тем, как «картотека Лумана», «нумерация», «бумажная или цифровая», «организация картотеки» и другие.

Что нужно для картотеки

Для ведения картотеки, вам понадобятся четыре инструмента:

«Больше вам не нужно, а меньшим не обойтись»

В принципе, один инструмент может сочетать в себе несколько или даже все четыре. Например, в Obsidian можно делать записи на ходу, делать заметки во время чтения, хранить основные заметки и писать статьи.

Для Лумана таким Обсидианом были бумажные карточки. Только книги и статьи он писал на печатной машинке.

Для ведения картотеки, Зонке советует использовать цифровые приложения, «хотя бы для мобильности». Подойдёт любой вариант, у которого есть теги и ссылки, например, Evernote или iA Writer. Лучше, если есть обратные ссылки — как в Obsidian или Roam. Сам Зонке рекомендует попробовать ZKN3 Даниеля Людке.

Если вы раздумываете, какой вариант выбрать: цифовой или аналоговый, рекомендую посмотреть видео Андрея Суховского. В нём он подробно разбирает все плюсы и минусы обоих подходов.

Если вам понравилась статья, подписывайтесь на рассылку, чтобы получать уведомления о новых статьях о ведении заметок, чтении и продуктивности на почту. Без спама, обещаю.

А если вам удобнее получать уведомления о новых статьях в Телеграме, подписывайтесь на мой канал.

Похожее

Retrieved 15 августа, 2022 at 13:48 (website time).

Andyʼs working notes

Ahrens, S. (2017). How to Take Smart Notes: One Simple Technique to Boost Writing, Learning and Thinking – for Students, Academics and Nonfiction Book Writers.

A core book on §Note-writing systems practice. Sönke focuses largely on the benefits of a Zettelkasten for the academic writing process. One of the core ideas here is that creative writing can become relatively closed-form and actionable; it can be made executable, GTD-style, through a series of steps drawing on a densely-connected note system.

Advice on associations

Keywords should be sparse and tightly curated. They’re meant mostly as a “jumping-off” point: the connections between notes will be the primary navigational device. Indexed references vs. tags Tags are an ineffective association structure

— c) Making sure you will be able to find this note later by either linking to it from your index or by making a link to it on a note that you use as an entry point to a discussion or topic and is itself linked to the index.

— In the Zettelkasten, keywords can easily be added to a note like tags and will then show up in the index. They should be chosen carefully and sparsely. Luhmann would add the number of one or two (rarely more) notes next to a keyword in the index (Schmidt 2013, 171).

— Because it should not be used as an archive, where we just take out what we put in, but as a system to think with, the references between the notes are much more important than the references from the index to a single note.

— The way people choose their keywords shows clearly if they think like an archivist or a writer. Do they wonder where to store a note or how to retrieve it? The archivist asks: Which keyword is the most fitting? A writer asks: In which circumstances will I want to stumble upon this note, even if I forget about it? It is a crucial difference.

We should beware automatic linkages. Prefer explicit associations to inferred associations

— Even though the Zettelkasten makes suggestions here, too, for example based on joint literature references, making good cross-references is a matter of serious thinking and a crucial part of the development of thoughts.

Advice on structuring the note archive

The important thing about project notes seems to be that they be separated from the durable notes.

— Project notes, which are only relevant to one particular project. They are kept within a project-specific folder and can be discarded or archived after the project is finished.

No need to treat every subject exhaustively: just write down what seems likely to help you think about the topics you’re pondering.

— Because the slip-box is not intended to be an encyclopaedia, but a tool to think with, we don’t need to worry about completeness. We don’t need to write anything down just to bridge a gap in a note sequence. We only write if it helps us with our own thinking.

Relative to memory systems

Flashcards need to be elaborated and embedded in a context.

— The information on flashcards is neither elaborated on nor embedded in some form of context. Each flashcard stays isolated instead of being connected with the network of theoretical frames, our experiences or our latticework of mental models.

Limitations of memory

— “Selection is the very keel on which our mental ship is built. And in this case of memory its utility is obvious. If we remembered everything, we should on most occasions be as ill off as if we remembered nothing. It would take as long for us to recall a space of time as it took the original time to elapse, and we should never get ahead with our thinking.” (William James 1890, 680).

Notes help you think accurately

Do your own thinking

— described in his famous text about the Enlightenment: “Nonage immaturity is the inability to use one’s own understanding without another’s guidance. This nonage is self-imposed if its cause lies not in lack of understanding but in indecision and lack of courage to use one’s own mind without another’s guidance. Dare to know! (Sapere aude.) ‘Have the courage to use your own understanding,’ is therefore the motto of the Enlightenment.” (Kant 1784)

— But the first question I asked myself when it came to writing the first permanent note for the slip-box was: What does this all mean for my own research and the questions I think about in my slip-box? This is just another way of asking: Why did the aspects I wrote down catch my interest?

Zettelkasten is more epistemologically honest, likely to find contrarian truths Evergreen notes are a safe place to develop wild ideas Writing forces sharper understanding

— Developing arguments and ideas bottom-up instead of top-down is the first and most important step to opening ourselves up for insight.

It’s hard to see what’s not said in a text. By integrating our reading observations with prior notes, we’re naturally confronted with rocks the author may have left unturned. Writing forces sharper understanding

— Experienced academic readers usually read a text with questions in mind and try to relate it to other possible approaches, while inexperienced readers tend to adopt the question of a text and the frames of the argument and take it as a given. What good readers can do is spot the limitations of a particular approach and see what is not mentioned in the text.

People inappropriately ignore note-taking

Most people are bad at writing notes, and they don’t know it, because the feedback is indirect and delayed. Note-writing practices are generally ineffective

— There is another reason that note-taking flies mostly under the radar: We don’t experience any immediate negative feedback if we do it badly.

Writing notes feels like a huge time imposition, but that’s in comparison to an imaginary baseline: reading without writing notes is often all lost time. Evergreen note-writing helps reading efforts accumulate

— And while writing down an idea feels like a detour, extra time spent, not writing it down is the real waste of time, as it renders most of what we read as ineffectual.

Notes help make creative insights happen

People fixate on writing books and papers, but those things don’t emerge fully formed: they’re the synthesis of lots of detailed thinking on those topics.

— focus lies almost always on the few exceptional moments where we write a lengthy piece, a book, an article or, as students, the essays and theses we have to hand in.

— Every intellectual endeavour starts from an already existing preconception, which then can be transformed during further inquires and can serve as a starting point for following endeavours. Basically, that is what Hans-Georg Gadamer called the hermeneutic circle (Gadamer 2004).

Brainstorming is a crutch…

— As proper note-taking is rarely taught or discussed, it is no wonder that almost every guide on writing recommends to start with brainstorming. If you haven’t written along the way, the brain is indeed the only place to turn to. On its own, it is not such a great choice: it is neither objective nor reliable – two quite important aspects in academic or nonfiction writing. The promotion of brainstorming as a starting point is all the more surprising as it is not the origin of most ideas: The things you are supposed to find in your head by brainstorming usually don’t have their origins in there. Rather, they come from the outside: through

— Many students and academic writers think like the early ship owners when it comes to note-taking. They handle their ideas and findings in the way it makes immediate sense: If they read an interesting sentence, they underline it. If they have a comment to make, they write it into the margins. If they have an idea, they write it into their notebook, and if an article seems important enough, they make the effort and write an excerpt. Working like this will leave you with a lot of different notes in many different places. Writing, then, means to rely heavily on your brain to remember where and when these notes were written down. A text must then be conceptualised independently from these notes, which explains why so many resort to brainstorming to arrange the resources afterwards according to this preconceived idea.

The note archive is a safe place for unjustified inklings to grow.

— Steven Johnson, who wrote an insightful book about how people in science and in general come up with genuine new ideas, calls it the “slow hunch.” As a precondition to make use of this intuition, he emphasises the importance of experimental spaces where ideas can freely mingle (Johnson 2011). A laboratory with open-minded colleagues can be such a space, much as intellectuals and artists freely discussed ideas in the cafés of old Paris. I would add the slip-box as such a space in which ideas can mingle freely, so they can give birth to new ones.

Morale while writing

Note-taking practices can turn writing into a predictable, actionable process (“start from abundance”). Executable strategy for writing

— To get a good paper written, you only have to rewrite a good draft; to get a good draft written, you only have to turn a series of notes into a continuous text. And as a series of notes is just the rearrangement of notes you already have in your slip-box, all you really have to do is have a pen in your hand when you read.

Evergreen notes permit smooth incremental progress in writing (“incremental writing”)

— As the outcome of each task is written down and possible connections become visible, it is easy to pick up the work any time where we left it without having to keep it in mind all the time.

— All this enables us to later pick up a task exactly where we stopped without the need to “keep in mind” that there still was something to do. That is one of the main advantages of thinking in writing – everything is externalised anyway.

Zettelkasten is a great release valve for editing. Material which isn’t essential for a particular piece can become a durable note, providing value later. Or, flipping this around, if the writing began with the note archive, then there’s no harm in deleting manuscript material, since it lives on elsewhere. Evergreen notes lower the emotional stakes in editing manuscripts

— One of the most difficult tasks is to rigorously delete what has no function within an argument – “kill your darlings.”42 This becomes much easier when you move the questionable passages into another document and tell yourself you might use them later.

sense of ease

— He not only stressed that he never forced himself to do something he didn’t feel like, he even said: “I only do what is easy. I only write when I immediately know how to do it. If I falter for a moment, I put the matter aside and do something else.” (Luhmann et al., 1987, 154f.)4

— “When I am stuck for one moment, I leave it and do something else.” When he was asked what else he did when he was stuck, his answer was: “Well, writing other books. I always work on different manuscripts at the same time. With this method, to work on different things simultaneously, I never encounter any mental blockages.”

— This is partly due to the aforementioned Zeigarnik effect (Zeigarnik 1927), in which our brains tend to stay occupied with a task until it is accomplished (or written down). If we have the finish line in sight, we tend to speed up, as everyone knows who has ever run a marathon.

Litmus test: all that matters is writing. All activities should lead to writing

— Focusing on writing as if nothing else counts does not necessarily mean you should do everything else less well, but it certainly makes you do everything else differently. Having a clear, tangible purpose when you attend a lecture, discussion or seminar will make you more engaged and sharpen your focus.

Unsorted

Abstraction is also the key to analyse and compare concepts, to make analogies and to combine ideas; this is especially true when it comes to interdisciplinary work (Goldstone and Wilensky 2008). Being able to abstract and re-specify ideas is, again, only one side of the equation. It is not good for anything if we don’t have a system in place that allows us to put this into practice. Here, it is the concrete standardization of notes in just one format that enables us to literally shuffle them around, to add one idea to multiple contexts and to compare and combine them in a creative way without losing sight of what they truly contain.

We don’t need to worry about the question of what to write about because we have answered the question already – many times on a daily basis. Every time we read something, we make a decision on what is worth writing down and what is not.

It is the one decision in the beginning, to make writing the mean and the end of the whole intellectual endeavour, that changed the role of topic-finding completely. It is now less about finding a topic to write about and more about working on the questions we generated by writing.

That is why we need to elaborate on it. But elaboration is nothing more than connecting information to other information in a meaningful way. The first step of elaboration is to think enough about a piece of information so we are able to write about it. The second step is to think about what it means for other contexts as well.

How to take smart notes (Ahrens, 2017)

This is my rephrasing of (Ahrens, 2017, How to Take Smart Notes). I added some personal comments.

The amazing note-taking method of Luhmann

To be more productive, it’s necessary to have a good system and workflow. The Getting Things Done system (collect everything that needs to be taken care of in one place and process it in a standardised way) doesn’t work well for academic thinking and writing, because GTD requires clearly defined objectives, whereas in doing science and creative work, the objective is unclear until you’ve actually got there. It’d be pretty hard to «innovate on demand». Something that can be done on demand, in a predetermined schedule, must be uncreative.

Enter Niklas Luhmann. He was an insanely productive sociologist who did his work using the method of «slip-box» (in German, «Zettelkasten»).

Making a slip-box is very simple, with many benefits. The slip-box will become a research partner who could «converse» with you, surprise you, lead you down surprising lines of thoughts. It would nudge you to (number in parenthesis denote the section in the book that talks about the item):

Four kinds of notes

Fleeting notes

These are purely for remembering your thoughts. They can be: fleeting ideas, notes you would have written in the margin of a book, quotes you would have underlined in a book.

They have no value except as stepping stones towards making literature and permanent notes. They should be thrown away as soon as their contents have been transferred to literature/permanent notes (if worthy) or not (if unworthy).

Jellyfish might be ethically vegan, since they have such a simple neural system, they probably can’t feel pain.

Literature notes

These summarize the content of some text, and give the citation.

Kahneman, Daniel, and Amos Tversky. “On the Psychology of Prediction.” Psychological Review (1973)

Such notes could be made in Zotero, which is how I do it. You might make them separately in some other notebook software, or just in plain text files.

Permanent notes

Each permanent note contains one idea, explained fully, in complete sentences, as if part of a published paper.

There are many tools available for storing the permanent notes, see Tools • Zettelkasten Method. I personally recommend TiddlyWiki.

Project notes

These are notes made only for a project, such as a note that collects all the notes that you’d want to assemble into a paper. They can be thrown away after the project is finished.

Four principles

Writing is the only thing that matters.

Don’t just read. Make reading notes. Don’t just learn. Make blog posts or something to share what you learned.

Also, hand-written notes has some advantage. In (Mueller & Oppenheimer, The Pen Is Mightier Than the Keyboard: Advantages of Longhand Over Laptop Note Taking, 2014), it’s shown that students who take notes by laptop understood lectures less, due to their tendency to transcribe verbatim without understanding. From mouth to ears to fingers, bypassing the brains completely.

The way I see it, this is not an argument against using the computer, but an argument for repharsing instead of copy-pasting/direct quoting/mere transcribing.

Be simple

Don’t underline, highlight, write in the margins, or use several complicated systems for annotation. It’d make it really hard for you to retrieve these scattered ideas later. You would be forced to remember with your biological brain to keep track of what information is put where.

Put all these ideas in the same simple system of your slip-box, and you will be set free to use your biological brain to think about these ideas.

Your simple slip-box system would be like an external brain that interfaces seamlessly with your biological brain.

Papers are linear, but writing is nonlinear

This is why advice on «how to write» in the form of a list of «do this then that» is bound to do badly.

Instead, you should write a lot of permanent notes in your slip-box. Then when the time comes for you to write a paper, just select a linear path out of the network of notes, then rephrase and polish that into a paper.

Calculate productivity not by how many pages of paper you’ve written, but by how many permanent notes you’ve written per day. This is because some pages of a paper can take months to write, others can take hours. In contrast, each permanent note takes roughly the same amount of time to write.

Short feedback loops

Feedback loops should be short. It makes you learn fast, fail fast, succeed fast. According to (Kahneman & Klein, Conditions for Intuitive Expertise: A Failure to Disagree, 2009), this is how intuitive expertise is made: a lot of practice in an environment with rapid and unambiguous feedback.

The traditional way of writing a paper takes months before you get a feedback in the form of reviewers’ comments. Instead, you should make notes, which you could make several per day, allowing fast feedback loops. If you really understood something, you’d see it in the form of a well-written note. If not, then you know you haven’t really understood it. You can experiment with other ways to make the notes and you will see immediately what works and what doesn’t.

Six methods

How to pay attention

Don’t multitask. Pay attention to one task at a time.

When writing, pay attention to the idea flow, what you want the words to mean. Don’t pay attention to what the words actually mean.

When proofreading, pay attention to what the words are saying, and not what you think they mean.

Pay attention only to what you must and don’t pay attention to anything else, because attention is very precious.

Routinize things that can be routinized, such as food, water, clothes. Wear only one outfit ever, like Steve Jobs. Eat only one meal plan, buy exactly the same kind of groceries, or better, always eat the first vegan meal plan at the canteen.

Use the Zeigarnik effect to your advantage. If you want something to stop intruding your mind, write it down and promise yourself that you’ll «deal with it later». If you want to keep pondering something (perhaps a problem you want to solve), don’t write it down, and go for a walk with that problem on your mind.

How to make literature notes

As mentioned before, each literature note contains exactly two parts: the content of a text, and the bibliographical location of the text. If you do the note in a bibliography software like Zotero, you can attach the note directly to the text, and there’s no need for the bibliography information.

The most important thing is to capture your understanding of the text, so don’t quote. Quoting can easily lead to out-of-context quoting. Preseve the context as much as possible by paraphrasing.

Prepare the literature notes so that when you make permanent notes, you can elaborate on the texts, that is, describe the context, find connections and contrasts and contradictions with other texts.

How to make permanent notes

Recontexutalize ideas in your thought. Write down why you would care about an idea. For example (from section 11.2), if the idea is an observation from (Mullainathan and Shafir, 2013, Scarcity: Why having too little means so much):

people with almost no time or money sometimes do things that don’t seem to make any sense. People facing deadlines sometimes switch frantically between all kinds of tasks. People with little money sometimes spend it on seeming luxuries like take-away food.

As someone with a sociological perspective on political questions and an interest in the project of a theory of society, my first note reads plainly:

Any comprehensive analysis of social inequality must include the cognitive effects of scarcity. Cf. Mullainathan and Shafir 2013.

How to link between notes

There are three kinds of links between notes:

At the top level, there is one note called «Index». The index note is just a list of tags/keywords with links. Each tag/keyword is a topic that you care about, and is linked to a few notes (Luhmann limited himself to at most 2) that serve as «entry points» to the topic.

The entry points are often notes that give overviews to the topic. Luhmann would make these notes to be an annotated list of notes that cover various aspects of the topic. His entry-point notes would have list length up to 25.

Between notes, there are two kinds of links: sequential and horizontal. In fact, sequential links are really just horizontal links that you annotate as «sequential».

For example, consider this note:

Content content content content .

After reading this note, you can go along the sequence and read «Followed by» notes, or take a sideways stride and follow the horizontal link .

The advantage of marking some links as sequential is that you get clear sequences of thought that you can easily follow, but they are by no means essential. You could just make horizontal links.

Ideally, you should make the network of slip-box notes to be like a small-world network, with a few notes having many connections, and some notes having «weak ties» to far-away notes (Granovetter, Mark S, 1977 The Strength of Weak Ties).

How to write a paper

Don’t brainstorm, since brainstormed ideas are what’s easily available, instead of innovative or actually relevant. Especially don’t group-brainstorm, which tend to become even less innovative due to groupthink effects (Mullen, Brian, Craig Johnson, and Eduardo Salas, 1991, Productivity Loss in Brainstorming Groups: A Meta-Analytic Integration).

Instead, do a walk through the slip-box and select a linear path. That gives you a draft from which you can polish into a paper.

Work on several papers simultaneously, switch if bored. This is a kind of «slow multitasking», which is good multitasking. Luhmann said

When I am stuck for one moment, I leave it and do something else. I always work on different manuscripts at the same time. With this method, to work on different things simultaneously, I never encounter any mental blockages.

When you need to cut out something that you really like, but just doesn’t belong to the paper (such as something that is not relevant to the argument), you can make a file named «maybe later.txt» and dump all the things that you promise to add back later (but never actually do). This is a psychological trick that works.

How to start the habit of using slip-boxes

Old habits die hard. The best way to break an old habit is to make a new habit that can hopefully replace the old habit.

For getting into the habit of using slip-boxes, you can start by making literature notes. Once you have that habit, making permanent notes would be a natural next habit to take on.