How the leopard got the spots

How the leopard got the spots

Онлайн чтение книги Откуда у Леопарда пятна How the Leopard got his Spots

И спросил Леопард Павиана (а денёк, замечу, выдался донельзя жаркий):

— Не знаешь, куда подевалась вся наша дичь?

И Павиан опустил веки. Он знал.

И спросил Эфиоп Павиана:

— Ведомо ли тебе нынешнее местонахождение аборигенной Фауны?

(Вообще-то он спросил то же самое, что и Леопард. Просто Эфиоп любил длинные слова. Он же был взрослый.)

И Павиан опустил веки. Ему было ведомо.

И сказал Павиан:

— Дичи свойственно линять; и я советую тебе, Леопард, последовать её примеру, и чем быстрее, тем лучше.

— Это всё, конечно, весьма любопытно, но я всё же хотел бы выяснить, в каком направлении мигрировала аборигенная Фауна?

И сказал Павиан:

— Аборигенная Фауна слилась с аборигенной Флорой, ибо настало время перемен; и я советую тебе, Эфиоп, тоже измениться, да поскорее.

Всё это че-рез-вычайно озадачило Леопарда и Эфиопа, и они отправились на поиски аборигенной Флоры. Они шли много-много дней и много-много ночей и наконец увидели огромный лес с высоченными деревьями, и лес этот был че-рез-вычайно тенист: весь он был испещрён, изрисован, исполосован, исчёркан и исчиркан, усыпан и обсыпан, расчерчен и размечен, изрезан и измазан, размалёван и заштрихован тенями. (Попробуй сказать это быстро — и ты поймёшь, до чего же он был тенистый, этот лес.)

— Что это такое? — спросил Леопард. — Вот это вот, че-рез-вычайно тёмное, но с кучей светлых пятнышек?

— Не знаю, — отвечал Эфиоп, — но, должно быть, это и есть аборигенная Флора. Я чую Жирафа, слышу Жирафа, но не вижу никакого Жирафа!

— Да, странное дело, — подхватил Леопард. — Наверно, это потому, что нам с тобой всё время было светло-светло, а тут — раз! — и так темно. Я чую Зебру, слышу Зебру, но не вижу никакой Зебры.

— Погоди-ка, — сказал Эфиоп. — Мы же на них давно не охотились. Может, мы просто забыли, как они выглядят?

— Чушь! — фыркнул Леопард. — Прекрасно я помню, как они выглядят. Особенно их мозговые косточки. Жираф — он футов семнадцать в высоту, весь такой желтовато-золотистый с головы до пят; а Зебра ростом фута четыре с половиной, и вся от пят до головы такая рыжевато-коричневатая.

— М-да, — проговорил Эфиоп, обводя взглядом тенисто-пятнистую аборигенную Флору. — На этом тёмном фоне они должны бросаться в глаза, как спелые бананы в коптильне!

Однако не тут-то было. Леопард и Эфиоп охотились весь день, с утра до вечера, и всё время чуяли дичь и слышали дичь, но никакой дичи не видели.

— Прошу тебя, — сказал Леопард, когда день уже клонился к закату, — давай дождёмся темноты. Эта охота при свете дня — просто стыд и срам.

И вот, когда стало темным-темно и только звёздный свет полосками падал сквозь ветки, Леопард услышал какое-то сопение; и он прыгнул в сторону этого сопения и ухватил то, что сопело; и то, что он ухватил, пахло Зеброй, и на ощупь было как Зебра, и когда он повалил это на землю, оно принялось лягаться, как Зебра, — но что это такое было, он совсем-совсем не видел и разглядеть никак не мог.

И сказал Леопард:

— Эй ты, невидимка, замри и не лягайся! Я всё равно не слезу с твоей головы до самого рассвета. А уж тогда-то я разгадаю твой секрет!

Вскоре Леопард услышал хрип, и хруст, и треск, а потом голос Эфиопа:

— Я кого-то поймал, а кого — не знаю! Пахнет, как Жираф, и лягается, как Жираф, только его не видно!

— Похоже, они тут все невидимые, — сказал Леопард. — Не верю я им. И ты не верь. Поймал — вот и сиди у него на голове до утра, как я. А там посмотрим.

И они просидели на головах у своей добычи, пока не настало утро, ясное и солнечное. И тогда Леопард сказал:

— Эй, брат Эфиоп, что там у тебя на завтрак?

И ответил Эфиоп, почесав голову:

— Поди пойми. Вроде бы это Жираф — но ведь Жираф должен быть ярко-рыже-жёлтым с головы до пят, а эта живность сплошь покрыта коричневыми пятнами! А что у тебя на завтрак, брат Леопард?

И ответил Леопард, почесав голову:

— Поди пойми. Вроде как Зебра, но ведь Зебра должна быть с головы до пят нежно-серо-бурой, а эта штуковина вся покрыта лилово-чёрными полосками. Что это ты с собой сотворила, Зебра? Ты разве забыла, что дома, в Высоком Вельде, я тебя за десять миль прекрасно видел? А теперь что? Теперь тебя не разглядеть!

— Вот именно, — отвечала Зебра. — Тут тебе не Высокий Вельд — не видишь, что ли?

— Теперь-то я всё вижу, — сказал Леопард. — А вчера не видел. Как вы это делаете?

— А вы нас отпустите, — сказала Зебра, — и мы вам покажем.

И Леопард с Эфиопом отпустили Жирафа и Зебру; и Зебра тут же отпрыгнула в колючие кусты, чья тень ложилась на землю полосками, а Жираф отскочил под высокие деревья, которые отбрасывали пятнистую тень.

— А теперь глядите, — хором сказали Зебра и Жираф. — Вот как мы это делаем. Раз, два, три! Ну, и где ваш завтрак?

Леопард во все глаза глядел туда, куда отпрыгнула Зебра, а Эфиоп — туда, куда отскочил Жираф, но ни Зебры, ни Жирафа они не видели, а видели они только тенистый-претенистый лес, с полосатыми тенями и пятнистыми тенями, — тот самый лес, где так ловко спрятались и Жираф, и Зебра.

— Ничего себе! — воскликнул Эфиоп. — Надо бы и нам выучиться этому фокусу. Учись, Леопард, а то торчишь, как кусок мыла в ведёрке с углём!

— На себя посмотри, — пробурчал Леопард. — Сам, между прочим, желтеешь тут, как горчичник на мешке угольщика!

— Сколько ни обзывайся, а есть всё равно хочется, — рассудил Эфиоп. — Мы с тобой чересчур заметны на фоне окружающей среды, это яснее ясного. Так что я, пожалуй, последую совету Павиана. Он сказал, что мне пора измениться; а поскольку менять мне нечего, кроме кожи, ею и займусь.

Леопард ушам своим не поверил:

— На что же ты её собрался менять?!

— На черновато-коричневатую, с лёгким багрянцем и отблеском синевы. Красиво и практично: кто хочет залечь в ложбинке или за деревом, тому такая кожа придётся в самый раз!

И Эфиоп — раз-два! — взял да и сменил свою кожу, и Леопард изумился ещё сильнее: он никогда прежде такого не видел.

— А как же я? — спросил он, когда Эфиоп вдел последний мизинчик в новенькую блестящую чёрную кожу.

— Тебе бы тоже не мешало послушаться Павиана. Он же посоветовал тебе линять.

— А я что? — возмутился Леопард. — Я так и сделал. Слинял быстренько сюда, причём вместе с тобой. И много мне от этого пользы?

— О-хо-хонюшки, — вздохнул Эфиоп. — Павиан совсем не о том говорил. Он не велел тебе носиться как угорелому по всей Южной Африке. Он всего лишь сказал, что надо полинять. Стать пятнистым, понимаешь?

— А вот возьмём, к примеру, Жирафа, — сказал Эфиоп. — Или, если ты предпочитаешь полоски, возьмём Зебру. Ты заметил, как вся эта пятнистость и полосатость полезна для их здоровья?

— М-да, — задумался Леопард. — Всё равно не хочу быть похожим на Зебру, ни за что на свете!

— Ну, решай, — пожал плечами Эфиоп. — Мне нравится с тобой охотиться, но если ты твёрдо намерен красоваться тут как подсолнух у просмолённого забора — тогда что ж, прощай, мне будет тебя не хватать.

— Ладно, — вздохнул Леопард. — Тогда пусть пятна. Только, пожалуйста, маленькие, аккуратные. Не желаю походить на Жирафа — ни за что и никогда!

— Я тебя легонько запятнаю, — успокоил его Эфиоп, — кончиками пальцев. На них видишь сколько ещё чёрной краски осталось? Постой-ка смирно.

Эфиоп сложил пальцы щепоткой (на них ещё оставалось полным-полно чёрной краски) и прижал к боку Леопарда, и к другому боку, и к спине, и ещё раз, и ещё, и ещё — и всякий раз, прикасаясь к Леопарду, он оставлял на нём пять крошечных чёрных пятнышек, точно пять лепестков. Глянь на любого Леопарда, моя радость, — и ты сразу их увидишь. Иногда пятнышки получались слегка смазанными — это там, где у Эфиопа дрогнула рука; но если вглядеться, то хорошо заметно, что их всегда пять — пять отпечатков, оставленных кончиками толстых чёрных пальцев.

— Вот теперь ты красавчик! — сказал Эфиоп. — На голой земле ты будешь точь-в-точь как груда камней, на груде камней — как пёстрый валун, на ветке — как солнечный свет, пробивающийся сквозь листву, а на тропинке тебя вообще никто не заметит. Вот это жизнь, да? Только представь — и сразу замурлычешь от радости!

— Тогда почему ты сам не стал пятнистым? — спросил Леопард.

— Нам, чёрным, больше пристал простой чёрный цвет, — сказал Эфиоп. — А теперь пойдём-ка поглядим, как там поживают господа Раз-Два-Три-Ну-И-Где-Ваш-Завтрак?

И с тех пор, моя радость, зажили они — лучше некуда. Вот и сказке конец.

Ах да, и ещё. Ты наверняка слышал, как взрослые говорят: «Разве может Эфиоп переменить свою кожу, а Леопард — свои пятна?» [4] Взрослые цитируют библейского пророка Иеремию. Утверждая, что избавиться от привычки к злым делам очень трудно, Иеремия вопрошал: может ли эфиоп переменить свою кожу, а леопард (в русских переводах — «барс») — свои пятна? Так вот: нету дыма без огня. Взрослые, конечно, мастера говорить глупости, но вряд ли им пришло бы в голову так упорно повторять эту глупость, если бы Эфиоп с Леопардом и впрямь однажды не сделали того, что сделали. Но больше, моя радость, они этого не сделают, я тебя уверяю. Им и так хорошо.

How the leopard really got his spots

In Kipling’s story, a hunter paints spots on a leopard to help it blend into the ‘speckly, patchy-blatchy shadows’. Photograph: Randy Wells/Corbis

In Kipling’s story, a hunter paints spots on a leopard to help it blend into the ‘speckly, patchy-blatchy shadows’. Photograph: Randy Wells/Corbis

More than a century after Rudyard Kipling offered his own explanation in the Just So Stories, scientists have revealed how the leopard got his spots.

The animals’ dark, rosette-like markings, and those of other wild cats, are evolution’s response to the creatures’ surroundings and to whether they hunt by day or night, say researchers at Bristol University.

Cats that hunt on open, rocky ground by daylight tend to have evolved plain-coloured coats, while those that pounce from rainforest tree branches typically sport dappled fur. In each habitat, the cat’s markings improve its camouflage and make it a more effective predator.

For smaller cats, fur colour can help them hide from larger carnivores.

Will Allen, a behavioural ecologist, studied the coat patterns of 35 wild cat species and compiled details of their habitats, hunting styles and when they went on the prowl.

Cats with complex and irregular markings, such as the familiar spotted leopard, were commonly found in dense, dark forests and hunted at night.

In Kipling’s 1902 tale, an Ethiopian hunter paints spots on a leopard to help it blend into the «speckly, patchy-blatchy shadows» of the forest.

«Apart from the painting part, Kipling was quite right,» said Allen. «The leopard got its spots from a life in forested habitats, where it made use of the trees and nocturnal hunting.»

Ten cats in Allen’s study had plain coats and lived in open, often barren landscapes. The sand cat is found in the arid deserts of Asia and Africa and has particularly furry feet to protect them from the scorching sands.

The plain-furred Pallas’s cat melts into the treeless steppes of central Asia, while the small Andean mountain cat has a silver-grey coat that matches the rocky landscape.

In some parts of the world, jaguars and leopards are completely black, an adaptation that only seems to arise in species that live in a diverse range of habitats.

In the study, Allen asked volunteers to match the fur of different wild cats to computer-generated coat patterns that varied from plain and simple to complex and irregular markings. When Allen compared the markings across the cat family tree, he found that similar patterns emerged quickly and several times during feline evolution.

Some cats appear to have markings that are not suited to their natural stalking grounds. The cheetah, for example, has a distinctive spotted coat but lives in the sparse deserts of sub-Saharan Africa.

But the animal’s impressive athleticism means it can reach more than 60 miles per hour in three seconds, and so it may rely less on camouflage than other cats.

How the Leopard Got His Spots

(We have slightly adapted the story at the end to fit in with modern mores).

Read by Natasha

HOW THE LEOPARD GOT HIS SPOTS

IN the days when everybody started fair, Best Beloved, the Leopard lived in a place called the High Veldt. ‘Member it wasn’t the Low Veldt, or the Bush Veldt, or the Sour Veldt, but the ‘sclusively bare, hot, shiny High Veldt, where there was sand and sandy-coloured rock and ‘sclusively tufts of sandy-yellowish grass. The Giraffe and the Zebra and the Eland and the Koodoo and the Hartebeest lived there; and they were ‘sclusively sandy-yellow-brownish all over; but the Leopard, he was the ‘sclusivest sandiest-yellowish-brownest of them all—a greyish-yellowish catty-shaped kind of beast, and he matched the ‘sclusively yellowish-greyish-brownish colour of the High Veldt to one hair. This was very bad for the Giraffe and the Zebra and the rest of them; for he would lie down by a ‘sclusively yellowish-greyish-brownish stone or clump of grass, and when the Giraffe or the Zebra or the Eland or the Koodoo or the Bush-Buck or the Bonte-Buck came by he would surprise them out of their jumpsome lives. He would indeed! And, also, there was an Ethiopian with bows and arrows (a ‘sclusively greyish-brownish-yellowish man he was then), who lived on the High Veldt with the Leopard; and the two used to hunt together—the Ethiopian with his bows and arrows, and the Leopard ‘sclusively with his teeth and claws—till the Giraffe and the Eland and the Koodoo and the Quagga and all the rest of them didn’t know which way to jump, Best Beloved. They didn’t indeed!

After a long time—things lived for ever so long in those days—they learned to avoid anything that looked like a Leopard or an Ethiopian; and bit by bit—the Giraffe began it, because his legs were the longest—they went away from the High Veldt. They scuttled for days and days and days till they came to a great forest, ‘sclusively full of trees and bushes and stripy, speckly, patchy-blatchy shadows, and there they hid: and after another long time, what with standing half in the shade and half out of it, and what with the slippery-slidy shadows of the trees falling on them, the Giraffe grew blotchy, and the Zebra grew stripy, and the Eland and the Koodoo grew darker, with little wavy grey lines on their backs like bark on a tree trunk; and so, though you could hear them and smell them, you could very seldom see them, and then only when you knew precisely where to look. They had a beautiful time in the ‘sclusively speckly-spickly shadows of the forest, while the Leopard and the Ethiopian ran about over the ‘sclusively greyish-yellowish-reddish High Veldt outside, wondering where all their breakfasts and their dinners and their teas had gone. At last they were so hungry that they ate rats and beetles and rock-rabbits, the Leopard and the Ethiopian, and then they had the Big Tummy-ache, both together; and then they met Baviaan—the dog-headed, barking Baboon, who is Quite the Wisest Animal in All South Africa.

Said Leopard to Baviaan (and it was a very hot day), ‘Where has all the game gone?’

And Baviaan winked. He knew.

Said the Ethiopian to Baviaan, ‘Can you tell me the present habitat of the aboriginal Fauna?’ (That meant just the same thing, but the Ethiopian always used long words. He was a grown-up.)

And Baviaan winked. He knew.

Then said Baviaan, ‘The game has gone into other spots; and my advice to you, Leopard, is to go into other spots as soon as you can.’

And the Ethiopian said, ‘That is all very fine, but I wish to know whither the aboriginal Fauna has migrated.’

Then said Baviaan, ‘The aboriginal Fauna has joined the aboriginal Flora because it was high time for a change; and my advice to you, Ethiopian, is to change as soon as you can.’

That puzzled the Leopard and the Ethiopian, but they set off to look for the aboriginal Flora, and presently, after ever so many days, they saw a great, high, tall forest full of tree trunks all ‘sclusively speckled and sprottled and spottled, dotted and splashed and slashed and hatched and cross-hatched with shadows. (Say that quickly aloud, and you will see how very shadowy the forest must have been.)

‘What is this,’ said the Leopard, ‘that is so ‘sclusively dark, and yet so full of little pieces of light?’

‘I don’t know, said the Ethiopian, ‘but it ought to be the aboriginal Flora. I can smell Giraffe, and I can hear Giraffe, but I can’t see Giraffe.’

‘That’s curious,’ said the Leopard. ‘I suppose it is because we have just come in out of the sunshine. I can smell Zebra, and I can hear Zebra, but I can’t see Zebra.’

‘Wait a bit, said the Ethiopian. ‘It’s a long time since we’ve hunted ’em. Perhaps we’ve forgotten what they were like.’

‘Fiddle!’ said the Leopard. ‘I remember them perfectly on the High Veldt, especially their marrow-bones. Giraffe is about seventeen feet high, of a ‘sclusively fulvous golden-yellow from head to heel; and Zebra is about four and a half feet high, of a’sclusively grey-fawn colour from head to heel.’

‘Umm, said the Ethiopian, looking into the speckly-spickly shadows of the aboriginal Flora-forest. ‘Then they ought to show up in this dark place like ripe bananas in a smokehouse.’

But they didn’t. The Leopard and the Ethiopian hunted all day; and though they could smell them and hear them, they never saw one of them.

‘For goodness’ sake,’ said the Leopard at tea-time, ‘let us wait till it gets dark. This daylight hunting is a perfect scandal.’

So they waited till dark, and then the Leopard heard something breathing sniffily in the starlight that fell all stripy through the branches, and he jumped at the noise, and it smelt like Zebra, and it felt like Zebra, and when he knocked it down it kicked like Zebra, but he couldn’t see it. So he said, ‘Be quiet, O you person without any form. I am going to sit on your head till morning, because there is something about you that I don’t understand.’

Presently he heard a grunt and a crash and a scramble, and the Ethiopian called out, ‘I’ve caught a thing that I can’t see. It smells like Giraffe, and it kicks like Giraffe, but it hasn’t any form.’

‘Don’t you trust it,’ said the Leopard. ‘Sit on its head till the morning—same as me. They haven’t any form—any of ’em.’

So they sat down on them hard till bright morning-time, and then Leopard said, ‘What have you at your end of the table, Brother?’

The Ethiopian scratched his head and said, ‘It ought to be ‘sclusively a rich fulvous orange-tawny from head to heel, and it ought to be Giraffe; but it is covered all over with chestnut blotches. What have you at your end of the table, Brother?’

And the Leopard scratched his head and said, ‘It ought to be ‘sclusively a delicate greyish-fawn, and it ought to be Zebra; but it is covered all over with black and purple stripes. What in the world have you been doing to yourself, Zebra? Don’t you know that if you were on the High Veldt I could see you ten miles off? You haven’t any form.’

‘Yes,’ said the Zebra, ‘but this isn’t the High Veldt. Can’t you see?’

‘I can now,’ said the Leopard. ‘But I couldn’t all yesterday. How is it done?’

‘Let us up,’ said the Zebra, ‘and we will show you.

They let the Zebra and the Giraffe get up; and Zebra moved away to some little thorn-bushes where the sunlight fell all stripy, and Giraffe moved off to some tallish trees where the shadows fell all blotchy.

‘Now watch,’ said the Zebra and the Giraffe. ‘This is the way it’s done. One—two—three! And where’s your breakfast?’

Leopard stared, and Ethiopian stared, but all they could see were stripy shadows and blotched shadows in the forest, but never a sign of Zebra and Giraffe. They had just walked off and hidden themselves in the shadowy forest.

‘Hi! Hi!’ said the Ethiopian. ‘That’s a trick worth learning. Take a lesson by it, Leopard. You show up in this dark place like a bar of soap in a coal-scuttle.’

‘Ho! Ho!’ said the Leopard. ‘Would it surprise you very much to know that you show up in this dark place like a mustard-plaster on a sack of coals?’

‘Well, calling names won’t catch dinner, said the Ethiopian. ‘The long and the little of it is that we don’t match our backgrounds. I’m going to take Baviaan’s advice. He told me I ought to change; and as I’ve nothing to change except my skin I’m going to change that.’

‘What to?’ said the Leopard, tremendously excited.

‘To a nice working blackish-brownish colour, with a little purple in it, and touches of slaty-blue. It will be the very thing for hiding in hollows and behind trees.’

So he changed his skin then and there, and the Leopard was more excited than ever; he had never seen a man change his skin before.

‘But what about me?’ he said, when the Ethiopian had worked his last little finger into his fine new black skin.

‘You take Baviaan’s advice too. He told you to go into spots.’

‘So I did,’ said the Leopard. I went into other spots as fast as I could. I went into this spot with you, and a lot of good it has done me.’

‘Oh,’ said the Ethiopian, ‘Baviaan didn’t mean spots in South Africa. He meant spots on your skin.’

‘What’s the use of that?’ said the Leopard.

‘Think of Giraffe,’ said the Ethiopian. ‘Or if you prefer stripes, think of Zebra. They find their spots and stripes give them per-feet satisfaction.’

‘Umm,’ said the Leopard. ‘I wouldn’t look like Zebra—not for ever so.’

‘Well, make up your mind,’ said the Ethiopian, ‘because I’d hate to go hunting without you, but I must if you insist on looking like a sun-flower against a tarred fence.’

‘I’ll take spots, then,’ said the Leopard; ‘but don’t make ’em too vulgar-big. I wouldn’t look like Giraffe—not for ever so.’

‘I’ll make ’em with the tips of my fingers,’ said the Ethiopian. ‘There’s plenty of black left on my skin still. Stand over!’

Then the Ethiopian put his five fingers close together (there was plenty of black left on his new skin still) and pressed them all over the Leopard, and wherever the five fingers touched they left five little black marks, all close together. You can see them on any Leopard’s skin you like, Best Beloved. Sometimes the fingers slipped and the marks got a little blurred; but if you look closely at any Leopard now you will see that there are always five spots—off five fat black finger-tips.

‘Now you are a beauty!’ said the Ethiopian. ‘You can lie out on the bare ground and look like a heap of pebbles. You can lie out on the naked rocks and look like a piece of pudding-stone. You can lie out on a leafy branch and look like sunshine sifting through the leaves; and you can lie right across the centre of a path and look like nothing in particular. Think of that and purr!’

So they went away and lived happily ever afterward, Best Beloved. That is all.

Oh, now and then you will hear grown-ups say, ‘Can the Ethiopian change his skin or the Leopard his spots?’ I don’t think even grown-ups would keep on saying such a silly thing if the Leopard and the Ethiopian hadn’t done it once—do you? But they will never do it again, Best Beloved. They are quite contented as they are.

I AM the Most Wise Baviaan, saying in most wise tones,

‘Let us melt into the landscape—just us two by our lones.’

People have come—in a carriage—calling. But Mummy is there.

Yes, I can go if you take me—Nurse says she don’t care.

Let’s go up to the pig-sties and sit on the farmyard rails!

Let’s say things to the bunnies, and watch ’em skitter their tails!

Let’s—oh, anything, daddy, so long as it’s you and me,

And going truly exploring, and not being in till tea!

Here’s your boots (I’ve brought ’em), and here’s your cap and stick,

And here’s your pipe and tobacco. Oh, come along out of it—quick.

How the leopard got its spots

Alan Turing is considered to be one of the most brilliant mathematicians of the last century. He helped crack the German Enigma code during the Second World War and laid the foundations for the digital computer. His only foray into mathematical biology produced a paper so insightful that it is still regularly cited today, over 50 years since it was published.

Modelling an embryo

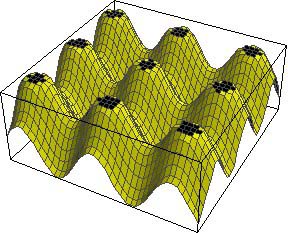

Turing’s paper described how «reaction-diffusion equations» might be used by animals to generate patterned structure during their development as an embryo. Animals start as a single cell that divides many times to create a full-size individual. During the early stages, the small ball of cells is completely uniform, or homogeneous, but out of this develop the dramatic patterns of a zebra, leopard, giraffe, butterfly or angelfish. Turing was interested in how a spatially homogeneous system, such as a uniform ball of cells, can generate a spatially inhomogeneous but static pattern, such as the stripes of a zebra. He managed to formulate a series of differential equations that, when solved, show very elegantly how the diversity of wonderful patterns on animals might be created.

Imagine an embryo with two types of chemical inside it. The two chemicals, as we will see, interact to generate patterns, and so are called morphogens (morpho from the Greek for «form», and gen from the Greek for «to beget»). For the sake of this discussion, we can imagine the embryo as a one-dimensional line and look at the concentration of each of the two morphogens at each point along the line. The chemicals can diffuse left and right along the line from a point of high concentration to lower concentration, and can also be produced afresh by cells along the embryo. One morphogen is an «Inhibitor» and suppresses the production of both itself and the other chemical. The other, an «Activator», promotes the production of both morphogens.

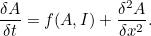

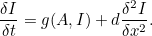

At any time (t) and any point along the embryo (x), the concentrations of the Activator and Inhibitor are given by A(x,t) and I(x,t) respectively. But these concentrations change over time due to new production (a reaction) and diffusion. The system is therefore known as a reaction-diffusion equation.

So the change of concentration of Activator over time can be written as the partial differential equation

|

The first term on the right-hand side describes how much Activator is being produced. It is a function of Activator and Inhibitor concentrations because they both affect the reaction rate. The second term is a second derivative describing how quickly the gradient of Activator is changing. It gives the rate of diffusion. The change of Inhibitor with respect to time is given by

|

Very perturbing

Say that, for whatever reason, the concentration of Activator increases slightly at one point. Now the local concentration of Activator is greater than Inhibitor, so more Activator is produced, and so on in a snowball effect. But Inhibitor is also being produced, and because it diffuses faster it quickly spreads to either side of the perturbation and decreases the concentration of Activator there. So you end up with a region of high Activator concentration bordered on both sides by high Inhibitor.

This process can be seen in the video to the right. As the animation steps through time the concentration of Activator along the embryo organises into a series of peaks.

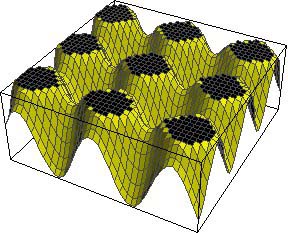

The reaction-diffusion equations can also be formulated for two dimensions. In this case an island of high Activator becomes surrounded by a moat of Inhibitor. Beyond this inhibitory halo, however, the levels of Inhibitor drop again and so other seeds can produce an area of high activator concentration. In this way the symmetry of the uniform concentration is broken into roughly evenly spaced regions of high Activator.

Revealing the pattern

An activator landscape

The Activator and Inhibitor are not colour pigments themselves, just the morphogens that interact to create an underlying pattern. If the Activator also promotes the generation of a pigment in the skin of the animal then this pattern can be made visible. Skin cells could produce yellow pigment unless they detect high levels of Activator instructing them to produce black. This would yield a visible pattern similar to that of a cheetah.

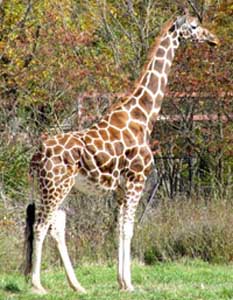

The size of these spots will depend on what are known as thresholds. The concentration of Activator can be thought of as a landscape of hills, with a certain concentration of Activator (i.e. altitude) required to turn ON the pigment. If this threshold is high, then only tiny spots at the very summit of the hills are seen, but if the threshold is lowered, then more of each hill is coloured and the spots are larger with less space between them. Such a mechanism may explain the difference in markings between two subspecies of giraffe: the Rothschild’s giraffe and the reticulated giraffe (shown at the top of this page), the first of which has smaller, more widely-spaced spots than the other.

A low threshold for turning pigment ON

A high threshold for turning pigment ON

Saturation can also be an important factor. If the concentration of Activator can reach a maximum value (ie. it is produced as fast as it breaks down or diffuses away) then the spots may join up into stripes. This is believed to be what happens in the zebra.

Size matters

The size of the embryo at the time of pattern generation is also very important. If the Inhibitor diffuses quickly relative to the size of the domain then few spots will be able to form. In fact, the stationary wave of Activator concentration is very similar to modes of vibration on a guitar string: only certain wavelengths can fit. The diagram below shows the reaction-diffusion simulation run on «embryos» of different sizes: 5, 30, 150 and 1000 units long. No pattern at all can form on small animals, and on very large animals the spots are too small-scale and seem to blend together.

Some developmental biologists have argued that this explains why neither small mice nor large elephants have any patterning. In between, however, more and more spots fit along the embryo. If d (the diffusion constant) is assumed to be the same for all mammals, then this would explain why hamsters have only a few patches of colour whilst leopards have hundreds of small spots.

The size of the domain also affects the type of patterns that can form. An animal’s tail can be thought of as a cylinder with a steadily decreasing radius. The top is large enough to support two-dimensional patterns like spots, but down at the bottom the domain becomes too small. The region of high Activator spreads all the way around the tail and joins up with itself, so that a spot becomes a stripe. The transition between spots and stripes is shown very well by a cheetah’s tail. This aspect of the maths also explains why a spotted animal can have a striped tail, but a striped animal can never have a spotted tail.

The process of pattern generation is completed in mammals during the embryonic stage. But some animals need to keep their markings up to date as they grow to full size. The stripes along the Marine angelfish move very slowly over time as the domain size increases. The basic bands on a young fish move apart as the fish grows, with new stripes appearing or dividing off existing ones to fill in any gaps.

Nature as Art?

The perturbations that trigger spots and stripes are usually statistical variations in the rate of morphogen production or diffusion. But physical disturbances from outside the embryo can have the same effect. The beautiful eyespots on butterfly wings are thought to rely on the principles described above, although involving more morphogens. Marta de Menezes produces art with living objects by pricking a butterfly wing with a pin while it is still developing in the chrysalis. This disrupts the concentration gradients and so alters the natural design.

Further reading

About this article

Lewis Dartnell read Biological Sciences at Queen’s College, Oxford. He took a year off to travel, but has now started a four-year MRes/PhD program in Bioinformatics at University College London’s Centre for multidisciplinary science, CoMPLEX. In 2003 he came second in the THES/OUP science writing competition with an article on the parallels between language and the structure of proteins.

Just So Stories/How the Leopard Got His Spots

HOW THE LEOPARD GOT HIS SPOTS

After a long time—things lived for ever so long in those days—they learned to avoid anything that looked like a Leopard or an Ethiopian; and bit by bit—the Giraffe began it, because his legs were the longest—they went away from the High Veldt. They scuttled for days and days and days till they came to a great forest, ‘sclusively full of trees and bushes and stripy, speckly, patchy-blatchy shadows, and there they hid: and after another long time, what with standing half in the shade and half out of it, and what with the slippery-slidy shadows of the trees falling on them, the Giraffe grew blotchy, and the Zebra grew stripy, and the Eland and the Koodoo grew darker, with little wavy grey lines on their backs like bark on a tree trunk; and so, though you could hear them and smell them, you could very seldom see them, and then only when you knew precisely where to look. They had a beautiful time in the ‘sclusively speckly-spickly shadows of the forest, while the Leopard and the Ethiopian ran about over the ‘sclusively greyish-yellowish-reddish High Veldt outside, wondering where all their breakfasts and their dinners and their teas had gone. At last they were so hungry that they ate rats and beetles and rock-rabbits, the Leopard and the Ethiopian, and then they had the Big Tummy-ache, both together; and then they met Baviaan—the dog-headed, barking Baboon, who is Quite the Wisest Animal in All South Africa.

This is Wise Baviaan, the dog-headed Baboon, Who is Quite the Wisest Animal in All South Africa. I have drawn him from a statue that I made up out of my own head, and I have written his name on his belt and on his shoulder and on the thing he is sitting on. I have written it in what is not called Coptic and Hieroglyphic and Cuneiformic and Bengalic and Burmic and Hebric, all because he is so wise. He is not beautiful, but he is very wise; and I should like to paint him with paint-box colours, but I am not allowed. The umbrella-ish thing about his head is his Conventional Mane.

Said Leopard to Baviaan (and it was a very hot day), ‘Where has all the game gone?’

And Baviaan winked. He knew.

Said the Ethiopian to Baviaan, ‘Can you tell me the present habitat of the aboriginal Fauna?’ (That meant just the same thing, but the Ethiopian always used long words. He was a grown-up.)

And Baviaan winked. He knew.

Then said Baviaan, ‘The game has gone into other spots; and my advice to you, Leopard, is to go into other spots as soon as you can.’

And the Ethiopian said, ‘That is all very fine, but I wish to know whither the aboriginal Fauna has migrated.’

Then said Baviaan, ‘The aboriginal Fauna has joined the aboriginal Flora because it was high time for a change; and my advice to you. Ethiopian, is to change as soon as you can.’

That puzzled the Leopard and the Ethiopian, but they set off to look for the aboriginal Flora, and presently, after ever so many days, they saw a great, high, tall forest full of tree trunks all ‘sclusively speckled and sprottled and spottled, dotted and splashed and slashed and hatched and cross-hatched with shadows. (Say that quickly aloud, and you will see how very shadowy the forest must have been.)

‘What is this,’ said the Leopard, ‘that is so ‘sclusively dark, and yet so full of little pieces of light?’

‘I don’t know,’ said the Ethiopian, ‘but it ought to be the aboriginal Flora. I can smell Giraffe, and I can hear Giraffe, but I can’t see Giraffe.’

‘That’s curious,’ said the Leopard. ‘I suppose it is because we have just come in out of the sunshine. I can smell Zebra, and I can hear Zebra, but I can’t see Zebra.’

‘Wait a bit,’ said the Ethiopian. ‘It’s a long time since we’ve hunted ’em. Perhaps we’ve forgotten what they were like.’

‘Fiddle!’ said the Leopard. ‘I remember them perfectly on the High Veldt, especially their marrow-bones. Giraffe is about seventeen feet high, of a ‘sclusively fulvous golden-yellow from head to heel; and Zebra is about four and a half feet high, of a ‘sclusively grey-fawn colour from head to heel.’

‘Umm,’ said the Ethiopian, looking into the speckly-spickly shadows of the aboriginal Flora-forest. ‘Then they ought to show up in this dark place like ripe bananas in a smokehouse.’

But they didn’t. The Leopard and the Ethiopian hunted all day; and though they could smell them and hear them, they never saw one of them.

For goodness’ sake,’ said the Leopard at tea-time, ‘let us wait till it gets dark. This daylight hunting is a perfect scandal.’

So they waited till dark, and then the Leopard heard something breathing sniffily in the starlight that fell all stripy through the branches, and he jumped at the noise, and it smelt like Zebra, and it felt like Zebra, and when he knocked it down it kicked like Zebra, but he couldn’t see it. So he said, ‘Be quiet, O you person without any form. I am going to sit on your head till morning, because there is something about you that I don’t understand.’

Presently he heard a grunt and a crash and a scramble, and the Ethiopian called out, ‘I’ve caught a thing that I can’t see. It smells like Giraffe, and it kicks like Giraffe, but it hasn’t any form.’

‘Don’t you trust it.’ said the Leopard. ‘Sit on its head till the morning—same as me. They haven’t any form—any of ’em.’

So they sat down on them hard till bright morning-time, and then Leopard said, ‘What have you at your end of the table, Brother?’

The Ethiopian scratched his head and said, ‘It ought to be ‘sclusively a rich fulvous orange-tawny from head to heel, and it ought to be Giraffe; but it is covered all over with chestnut blotches. What have you at your end of the table, Brother?’

And the Leopard scratched his head and said, ‘It ought to be ‘sclusively a delicate greyish-fawn, and it ought to be Zebra; but it is covered all over with black and purple stripes. What in the world have you been doing to yourself, Zebra? Don’t you know that if you were on the High Veldt I could see you ten miles off? You haven’t any form.’

‘Yes,’ said the Zebra, ‘but this isn’t the High Veldt. Can’t you see?’

‘I can now,’ said the Leopard. ‘But I couldn’t all yesterday. How is it done?’

‘Let us up,’ said the Zebra, ‘and we will show you.’

They let the Zebra and the Giraffe get up; and Zebra moved away to some little thorn-bushes where the sunlight fell all stripy, and Giraffe moved off to some tallish trees where the shadows fell all blotchy.

‘Now watch,’ said the Zebra and the Giraffe. ‘This is the way it’s done. One—two—three! And where’s your breakfast?’

Leopard stared, and Ethiopian stared, but all they could see were stripy shadows and blotched shadows in the forest, but never a sign of Zebra and Giraffe. They had just walked off and hidden themselves in the shadowy forest.

‘Hi! Hi!’ said the Ethiopian. That’s a trick worth learning. Take a lesson by it, Leopard. You show up in this dark place like a bar of soap in a coal-scuttle.’

‘Ho! Ho!’ said the Leopard. ‘Would it surprise you very much to know that you show up in this dark place like a mustard-plaster on a sack of coals?’

‘Well, calling names won’t catch dinner,’ said the Ethiopian. ‘The long and the little of it is that we don’t match our backgrounds. I’m going to take Baviaan’s advice. He told me I ought to change; and as I’ve nothing to change except my skin I’m going to change that.’

What to?’ said the Leopard, tremendously excited.

‘To a nice working blackish-brownish colour, with a little purple in it, and touches of slaty-blue. It will be the very thing for hiding in hollows and behind trees.’

So he changed his skin then and there, and the Leopard was more excited than ever; he had never seen a man change his skin before.

‘But what about me?’ he said, when the Ethiopian had worked his last little finger into his fine new black skin.

‘You take Baviaan’s advice too. He told you to go into spots.’

‘So I did,’ said the Leopard. ‘I went into other spots as fast as I could. I went into this spot with you, and a lot of good it has done me.’

‘Oh,’ said the Ethiopian, ‘Baviaan didn’t mean spots in South Africa. He meant spots on your skin.’

‘What’s the use of that?’ said the Leopard.

‘Think of Giraffe,’ said the Ethiopian. ‘Or if you prefer stripes, think of Zebra. They

How the Leopard Got His Spots

find their spots and stripes give them per-fect satisfaction.’

‘Umm,’ said the Leopard. ‘I wouldn’t look like Zebra—not for ever so.’

‘Well, make up your mind,’ said the Ethiopian, ‘because I’d hate to go hunting without you, but I must if you insist on looking like a sun-flower against a tarred fence.’

I’ll take spots, then,’ said the Leopard; ‘but don’t make ’em too vulgar-big. I wouldn’t look like Giraffe—not for ever so.’

Til make ’em with the tips of my fingers,’ ‘said the Ethiopian. ‘There’s plenty of black left on my skin still. Stand over!’

Then the Ethiopian put his five fingers close together (there was plenty of black left on his new skin still) and pressed them all over the Leopard, and wherever the five fingers touched they left five little black marks, all close together. You can see them on any Leopard’s skin you like, Best Beloved. Sometimes the fingers slipped and the marks got a little blurred; but if you look closely at any Leopard now you will see that there are always five spots—off five fat black finger-tips.

‘Now you are a beauty!’ said the Ethiopian.

This is the picture of the Leopard and the Ethiopian after they had taken Wise Baviaan’s advice and the Leopard had gone into other spots and the Ethiopian had changed his skin. The Ethiopian was really a negro, and so his name was Sambo. The Leopard was called Spots, and he has been called Spots ever since. They are out hunting in the spickly-speckly forest, and they are looking for Mr. One-Two-Three-Where’s-your-Breakfast. If you look a little you will see Mr. One-Two-Three not far away. The Ethiopian has hidden behind a splotchy-blotchy tree because it matches his skin, and the Leopard is lying beside a spickly-speckly bank of stones because it matches his spots. Mr. One-Two-Three-Where’s-your-Breakfast is standing up eating leaves from a tall tree. This is really a puzzle-picture like ‘Find the Cat.’

‘You can lie out on the bare ground and look like a heap of pebbles. You can lie out on the naked rocks and look like a piece of pudding-stone. You can lie out on a leafy branch and look like sunshine sifting through the leaves; and you can lie right across the centre of a path and look like nothing in particular. Think of that and purr!’

‘But if I’m all this,’ said the Leopard, ‘why didn’t you go spotty too?’

‘Oh, plain black’s best for a nigger,’ said the Ethiopian. ‘Now come along and we’ll see if we can’t get even with Mr. One-Two-Three-Where’s-your-Breakfast!’

So they went away and lived happily ever afterward, Best Beloved. That is all.

Oh, now and then you will hear grown-ups say, ‘Can the Ethiopian change his skin or the Leopard his spots?’ I don’t think even grown-ups would keep on saying such a silly thing if the Leopard and the Ethiopian hadn’t done it once—do you? But they will never do it again, Best Beloved. They are quite contented as they are.